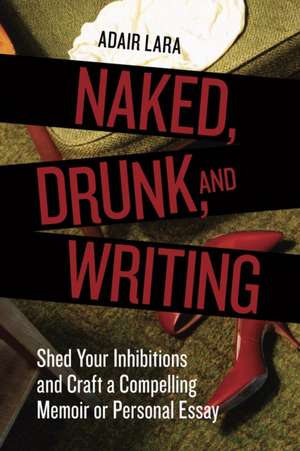

Naked, Drunk, and Writing: Shed Your Inhibitions and Craft a Compelling Memoir or Personal Essay

Autor Adair Laraen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2010

Enter Adair Lara: award-winning author, seasoned columnist, beloved writing coach, and the answer to all of your autobiographical quandaries.

Naked, Drunk, and Writing is the culmination of Lara’s vast experience as a writer, editor, and teacher. It is packed with insights and advice both practical (“writing workshops you pay for are the best--it’s too easy to quit when you’ve made no investment”) and irreverent (“apply Part A [butt] to Part B [chair]”), answering such important questions as:

• How do I know where to start my piece and where to end it?

• How do I make myself write when I’m too scared or lazy or busy?

• What makes a good pitch letter, and how do I get mine noticed?

• I’m ready to publish—now where do I find an agent?

• If I show my manuscript to my mother, will I ever be invited to a family gathering again?

As thorough and instructive as a personal writing coach (and cheaper, too), Naked, Drunk, and Writing is a must-have if you are an aspiring columnist, essayist, or memoirist—or just a writer who needs a bit of help in getting your story told.

Preț: 109.54 lei

Nou

20.97€ • 21.61$ • 17.70£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 10-24 februarie

Specificații

ISBN-10: 158008480X

Pagini: 248

Ilustrații: ONE COLOR

Dimensiuni: 142 x 209 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Ediția:Revised

Editura: Ten Speed Press

Recenzii

--ANNE LAMOTT, author of Bird by Bird

Cuprins

Part I: Writing Down Your Stories 1

one That Which Is Most Personal Is Most Common 2

two Hot Heart, Cold Eye: The Inconvenient Importance of Craft 8

Part II: The Personal Essay 11

three Elements of the Successful Essay 12

KEEP IT SMALL | 13

WHAT QUESTION DRIVES YOUR ESSAY? | 14

WRITE ABOUT THE MOMENT SOMETHING CHANGED | 15

BUILD THE ESSAY | 19

OUTLINE THE ESSAY | 22

WRITE THE EPIPHANY | 24

four What’s Your Angle? 34

YOU HAVE A SUBJECT—BUT DO YOU HAVE AN ANGLE? | 35

HOW TO FIND AN ANGLE | 37

HOW TO USE SETUP | 40

Part III: Techniques and Practices for Essay and Memoir 43

five Tone: How to Assert a Specific Temperament 45

ARE YOU FUNNY? | 47

BE A SCREWUP | 54

WATCH YOUR TONE | 56

FINDING YOUR VOICE: DO YOU SOUND LIKE YOU? | 59

six Image: The Luminosity of the Particular 62

USE YOUR SENSES | 65

BUILD IMAGES WITH SPECIFIC DETAILS | 69

THE DREAD NECESSITY OF INNER EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE | 75

seven How to Trick Yourself into Writing 80

APPLY PART A (BUTT) TO PART B (CHAIR) | 82

WRITE EVERY DAY | 85

NO TIME TO WRITE? CONSIDER YOURSELF LUCKY | 86

LOWER YOUR STANDARDS | 87

eight It Takes a Village: Working with Other Writers 90

HOW WRITING PARTNERS MAKE YOU WRITE | 91

HOW THE WRITING PARTNERSHIP WORKS | 93

TAKE CLASSES | 96

JOIN A GROUP | 98

FEEDBACK: HOW TO GIVE IT | 100

FEEDBACK: HOW TO TAKE IT | 104

nine Revising Rewriting Your Work 108

STEP BACK FROM YOUR DRAFT | 110

FIX THE BEGINNING | 112

FIX THE ENDING | 114

FIX IN GENERAL | 116

FIX THE SENTENCES | 121

HOW DO YOU KNOW WHEN YOU’RE FINISHED? | 126

Part IV: The Memoir 127

ten Planning Your Memoir 128

WILL YOUR IDEA WORK? | 129

USE REFLECTIVE VOICE | 134

DO YOUR REASEARCH| 141

ORGANIZE YOUR MATERIAL | 144

WRITE A DISCOVERY DRAFT | 145

eleven What Goes In, What Doesn’t 148

IDENTIFY YOUR DESIRE LINE AND OBSTACLES | 148

DETERMINE THE PIVOTAL EVENTS | 151

DRAW THE ARC | 154

STRENGTHEN THE ARC | 158

WHY IT’S CALLED CREATIVE NONFICTION | 163

HIRE AN EDITOR | 164

CONSIDER A NONCONVENTIONAL STRUCTURE | 166

twelve How to Write Narration and Scene 168

THE USES OF NARRATION | 168

WRITE COMPELLING SCENES | 170

BRING YOUR MOM TO LIFE | 175

USE DIALOGUE | 180

Part V: Getting Published 183

thirteen Words for Money: Selling Your Essays 184

WHERE TO FIND A MARKET | 188

HOW TO FIND HOOKS | 193

A WORD ABOUT RIGHTS | 195

HOW TO SUBMIT | 196

HOW TO HANDLE REJECTIONS | 200

HOW TO HANDLE ACCEPTANCES | 202

GET YOUR WORK OUT THERE | 203

fourteen Publishing Your Memoir 204

FIND AN AGENT | 205

PREPARE TO OBSESS OVER THE QUERY LETTER | 207

PUT TOGETHER THE PROPOSAL | 209

YOUR NEW JOB: PROMOTING YOUR BOOK | 213

SHOULD YOU SELF-PUBLISH? | 215

WHAT IF MOM READS IT? | 218

CONSIDER YOUR OPTIONS | 220

What You Get When You Write from Life 225

Appendix 231

READING LIST | 231

USEFUL TEXTS | 231

WRITING EXERCISES | 232

TRICKS OF THE (COMPUTER) TRADE | 241

Contributors 243

Index 244

About the Author 248

Notă biografică

ADAIR LARA wrote a twice-weekly column for the San Francisco Chronicle for twelve years, taught in the MFA program at Mills College, and won the Associated Press Award for Best Columnist in California. She leads sold-out writing workshops in San Francisco, CA.

Extras

What’s Your Angle?

There may never be anything new to say, but there is always a new way to say it.

—flannery o’connor

My friend Stan Sinberg, then a columnist for the Marin Independent Journal, had a big birthday coming up, and he wanted to write about it. Of course Stan could have just blurted out to his readers that he was about to be forty and realized many of his dreams remained unfulfilled. But that would be the direct approach. In life, directness is good. In writing, not so good. It’s said that when Henry James received a manuscript he didn’t like, he’d return it with the dry comment, “You have chosen a good subject and are treating it in a straightforward manner.”

You can’t just come out and say what you have to say. That’s what people do on airplanes, when a man plops down next to you in the aisle seat of your flight to New York, spills peanuts all over the place (back when the cheapskate airlines at least gave you peanuts), and tells you about what his boss did to him the day before. You know how your eyes glaze over when you hear a story like that? That’s because of the way he’s telling his story. You need a good way to tell your story.

An angle is a way to tell a story. It is to the essay what a premise is to a book, or a handle is to advertising, or a high concept is to a movie (dinosaurs brought back to life for a theme park!). It’s a gimmick or twist or conceit that grabs the reader’s attention long enough for you to say what you want to say. Think of the angle as the Christmas tree. Once you have that six-foot pine standing up next to the piano, it’s pretty easy to see where the decorations go. Without the tree, what have you got? A lot of pretty balls on the floor.

Remember Stan, who had a big birthday coming up? He needed a new way to take stock of his accomplishments when he turned forty. The first few lines establish the angle in Stan’s humorous twist on the subject:

Listen, I can’t spend a lot of time on today’s column because there’s a lot I have to do. See, today’s the last day I’m thirty-nine years old, and there’re all these things I always wanted to accomplish before I turned forty. Like get married. Always wanted to be married before I turned forty.

Stan’s angle was that he had to realize all his dreams on that final day of being thirty-nine. No problem with the marriage thing (“I’d had my eye on this woman who came into the health club most mornings at eleven”), but he also had to write a novel (“Fortunately, I have a couple of ideas”), and acquire kids, a house, a horse, and a piano. He was going to have a busy day.

Angles are half the battle, so when you find one it’s often almost not an exaggeration to say you are practically done, except for the typing. Stand up, stretch, and go eat the leftover chicken in the fridge. Angles make the rest of the piece easy, because often what follows is the easiest thing in the world to write: a list. You just have to come up with your points and pick an order for them. Notice that Stan’s account of all the things he needed to do before turning forty is such a list: he could start with the piano, and then talk about kids, and the piece would still work.

You Have a Subject—But Do You Have an Angle?

When a writer talks about having an idea for a piece, he usually means not that he has found a subject to write about, but that he has found an angle. When I wanted to write about mothers and their middle-aged daughters for MORE magazine, I had a subject. When I proposed a piece about how daughters start to take it easy on their mothers in middle age, I had an angle. Even when an essay is a chronological narrative—here’s my story of life as a black woman in America—finding an angle will sharpen it, as Zora Neale Hurston did when she began, “I remember the very day that I became colored.” Note the surprise in that statement: People don’t become colored; they discover they are. An angle always has an element of surprise—that’s the thing that makes it new.

Once I assigned a class to write about the same subject: Barbie dolls. Everybody returned with a different angle. One woman said she was a Barbie doll, another talked about how the pressure of keeping Barbie well dressed turned her into a shoplifter, a man said he pretended to hate Barbie—burning her hair off over the gas jets—but was more drawn to her than he let on. A student named Lisa Pongrace found her angle in a remark she happened to make in her first draft:

Barbie is regarded to be the standard of feminine perfection, yet Barbie isn’t perfect at all-her arms don’t even bend! She carries out a tray of frosty beverages, balancing it on the two bamboo poles they’ve given her for arms. She can’t even curl her fingers.

Like the outline of a narrative essay, the angle lets you know what to put in, what to leave out. Now that Lisa knows that her piece will be on Barbie’s imperfections, she will focus the next draft on that. If she talks about Barbie’s stunning array of careers, for example, she might observe that a flighty resume hardly demonstrates seriousness of purpose.

using conflict as angle

Sometimes your angle is bringing conflict into the piece when it needs it. It’s not enough to write a piece about how much you like to spend the day in bed. You always have to tell us what’s stopping you, or the piece will lack tension and thus have the gripping quality of a Hallmark card.

Often, of course, there is no trouble. The trip was wonderful in every respect, the new boyfriend is heaven sent, you are floating in a sky-blue pool in a Caribbean resort, and your only source of distress is that the tiny umbrella from your drink fell in the water.

One fix is to bring into the piece something or somebody who’s preventing you from doing what you want to do. If I want to write about how I nervously arrive hours early for a flight, maybe even get a hotel room at the airport the night before just to make sure, I have a topic, but where’s the tension? Who cares when I like to get to the airport? So I bring in someone with the opposite point of view—in this case, my husband, Bill, who prefers that last-minute swan dive into the 747 as it pulls away from the gate.

This is why, incidentally, columnists always cast their partners in the straight man role—to be the “You can’t do that” obstacle. You can use the same technique. Bring in a friend, a boss, or a mother (mothers are fabulous for this) to oppose you.

How to Find an Angle

If you’re struggling to come up with a compelling angle, here are some techniques and resources to try out. An interesting angle can come from any of the following sources.

the daily paper

I collect newspaper clippings that offer promising angles. One is a Miss Manners column with the headline, “A Move to Abolish the High School Prom.” For anyone wanting to write the story of her own high school prom, there’s an angle right there. Who cares if everybody has a terrible time at the prom? We had to go through it, and the next generation should have to, too.

something you hear yourself say aloud

I was having Thai food with my friend John when I remarked to him that my husband, Bill, and I kept all our finances separate. “We don’t even have a joint banking account.” My friend stared as if I had lifted a door in my skin and revealed a howling wilderness where sunshine and a lawn should be. “It doesn’t sound romantic, but it is,” I rushed to assure him. “We’ve practically never had an argument about money.” When I heard myself saying that, I jotted the idea on my napkin: “Divvying up finances like college roommates can be romantic.” That statement contains surprise, so it makes a promising angle.

talking the piece through with someone

“I’m not sure where to start, I seem to have two separate problems, the ending seems weak, what the hell is my epiphany?” and so on. If you don’t have a writing partner, follow that other human you live with around the house. “See, I’m trying to write about the plane crash that killed my whole skating team after I missed the flight, and I never understood . . .”

Your housemate can yawn, or keep folding the towels, shaving, or even watching TV—it doesn’t matter. It’s what you hear yourself saying that does the trick. A few years ago I’d been trying to find a way to write about a dark painting my mother made that showed my six siblings and me at the swimming hole in Samuel P. Taylor Park in Northern California, near where I grew up.

“She painted in all the shadows,” I commented to my husband, Bill, as I hung the painting in the hall, “but I remember all the sunlight.” Bingo. Angle.

writing the last paragraph

You can sometimes coax out an angle by writing a final paragraph, an exercise that’s just to help you think. I do this often. In this paragraph you type, “I don’t know what I’m trying to say here. What am I saying about my high school reunion? Am I trying to say this? Or that?” Just as when you talk a piece through with someone, if you force yourself to focus on what you’re driving at, you find you know—or your typing fingers do.

a remark you made in an early draft

A student of mine set down some thoughts about being confined to an apartment in Iran with her sister one long summer when their father was on assignment there. When she wrote, “The closer we were kept together, the more we grew apart,” she had her angle.

Similarly, my former writing partner, Ginny McReynolds, a college dean, said in a piece about lesbian potlucks, “It’s like so many other things in the lesbian community. For many lesbians, putting a lot of energy into something that is traditionally female seems wrong.” Angle! If she used that angle throughout the essay, she’d talk about the potluck, but also add other examples of lesbians balking at makeup or housekeeping or fancy clothes.

a quote

I read a magazine piece in which the writer muses, “I wonder: Do health concerns simply represent a more mature way of hating your body?” That’d be a good angle on the current obsession with health. Or, if you are just moving in with someone, you could play with a remark Robert Kaplan, a psychologist practicing in Oakland, made: the amount of our furniture we bring with us represents how much of our past we’re willing to give up on, share, or ignore.

I read somewhere about a mother with a sick baby who says at one point, “It’s all very hard, but there’s a lot of collateral beauty along the way.” That would be a good angle for a piece, as would this line from Salman Rushdie’s book, The Moor’s Last Sigh: “Every child creates the father she needs.”

I found an angle for a piece about the messy apartment I shared with my kids when I read the following quote, attributed to Herbert Muschamp, in HG Magazine: “We want a place for everything, but not necessarily everything in its place.” My piece began, “The upended picnic cooler serving as a fourth chair in my kitchen illuminated what Herbert Muschamp must have meant when he said . . .”

surprising remarks you hear

I once heard a woman say, “I’ve got four sisters and am always amazed that I’m the only one who remembers all family events exactly as they happened.” Another woman I know, referring to a crooked curtain rod in her entryway, commented, “That’s the kind of thing it takes a year and fifteen minutes to do.” Both of those are good possible angles.

How to Use Setup

Setup can be another effective way to structure a piece and is thus a kind of angle. In setup, you begin the piece with the opposite of where you want to go. (We saw a bit of this in the last chapter, when we talked about constructing an essay by working backward from the epiphany.)

Here’s an example of how setup works: One day San Francisco Chronicle columnist Jon Carroll was attending a wedding reception and he realized he was boring the bride he was talking to. Naturally, any such bad moment has potential, but a major metropolitan paper doesn’t hire people to turn out columns that say, “I had a troubling experience the other day that I’d like to tell you about.” In order to write about that moment of humiliation, Jon set it up by starting with the opposite: how nice it is, as a celebrated Bay Area columnist, to be recognized and admired:

Nice wedding last weekend. Very fine pizza; always a plus at a wedding. Lovely couple. Sweet music. Chocolate wedding cake-why doesn’t everyone think of that? Fans. I don’t mean to be immodest, but try to stop me. I am standing there in my extremely lovely Italian suit (the kind that causes people to involuntarily finger the sleeve and say, “I had no idea that you owned a suit like that, or at all”), eating a nectarine and gazing benignly into the mystic . . .

Then the fall, which appeared near the end of the column:

I look into Shana Morrison’s eyes. [The bride was Shana Morrison, the daughter of Van Morrison.] She is looking at me with devastating politeness. She is waiting for my rap to end. She’s done this before-her father has a lot of really old fans with obscure enthusiasms. I am the old guy at the wedding. My face is close to hers, and I’m sure my breath smells of whiskey and cigarettes and denture cream, though I’ve stopped using the first two and have not yet started the third.

Just as Jon wrote about humiliation by starting with how famous he is, Betsy Carter, in a piece in Glamour, wrote about hanging onto people by first talking about throwing things out. “When in doubt, toss it. That’s pretty much how I live my life. I have been known to throw away paychecks and dump IRS forms. The only thing I seem unable to shed is people.”

There’s no reason for us to know Carter threw out her checks—what do her feckless accounting methods have to do with anything? Those details are there to set up the contrast—throwing out versus keeping—that gives the piece its structure. Without it, you have the direct approach again: a writer tugging on your sleeve and telling you how she likes to hang on to people, from ex-husbands to dentists.

Another example? Virginia Woolf began a piece called “Professions for Women” by talking about how easily she became a writer: “When I came to write,” she said, “there were very few material obstacles in my way.” Writing was a reputable occupation, she said, the scratching of a pen disturbed no family peace, and paper was cheap. She quickly sold a piece about a Persian cat that brought her into disputes with her neighbors. “What could be easier,” she said, “than to write articles and to buy Persian cats with the profits?”

A lot, it turns out. That was the setup. The rest of the piece lists the harsh obstacles that impeded the woman writer in her day. If she had started by saying, “It’s hard for a woman to become a writer,” and then just listed the reasons, we’d have no surprise.

When you become aware of setup you see it everywhere, especially in the movies. When my husband, Bill, and I watch war movies, and a weary soldier leaning on his rifle starts talking about that little farm he’s going to buy when this is over, we look at each other and say in unison, “He’s dead.”

Setup: The dream that shows how much the character has to live for.

Payoff: Oops. Where’d that grenade come from?

Okay, that’s a joke, but it’s one that leads into the next chapter, on tone and humor.

Descriere

The material is right there in front of you. You’ve known yourself for, well, a lifetime—and you finally feel ready to share your story with the world. Yet when it actually comes time to put pen to paper, you find that you’re stumped.

Enter Adair Lara: award-winning author, seasoned columnist, beloved writing coach, and the answer to all of your autobiographical quandaries.

Naked, Drunk, and Writing is the culmination of Lara’s vast experience as a writer, editor, and teacher. It is packed with insights and advice both practical (“writing workshops you pay for are the best--it’s too easy to quit when you’ve made no investment”) and irreverent (“apply Part A [butt] to Part B [chair]”), answering such important questions as:

• How do I know where to start my piece and where to end it?

• How do I make myself write when I’m too scared or lazy or busy?

• What makes a good pitch letter, and how do I get mine noticed?

• I’m ready to publish—now where do I find an agent?

• If I show my manuscript to my mother, will I ever be invited to a family gathering again?

As thorough and instructive as a personal writing coach (and cheaper, too), Naked, Drunk, and Writing is a must-have if you are an aspiring columnist, essayist, or memoirist—or just a writer who needs a bit of help in getting your story told.