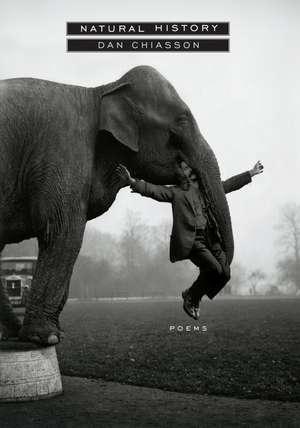

Natural History: Poems

Autor Dan Chiassonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2007

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

“What happens next, you won’t believe,” Chiasson writes in “From the Life of Gorky,” and it is fair warning. This collection suggests that a person is like a world, full of mysteries and wonders–and equally in need of an encyclopedia, a compendium of everything known. The long title sequence offers entries such as “The Sun” (“There is one mind in all of us, one soul, / who parches the soil in some nations / but in others hides perpetually behind a veil”), “The Elephant” (“How to explain my heroic courtesy?”), “The Pigeon” (“Once startled, you shall feel hours of weird sadness / afterwards”), and “Randall Jarrell” (“If language hurts you, make the damage real”). The mysteriously emotional individual poems coalesce as a group to suggest that our natural world is populated not just by fascinating creatures–who, in any case, are metaphors for the human as Chiasson considers them– but also by literature, by the ghosts of past poetries, by our personal ghosts. Toward the end of the sequence, one poem asks simply, “Which Species on Earth Is Saddest?” a question this book seems poised to answer. But Chiasson is not finally defeated by the sorrows and disappointments that maturity brings. Combining a classic, often heartbreaking musical line with a playful, fresh attack on the standard materials of poetry, he makes even our sadness beguiling and beautiful.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 124.15 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 186

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.76€ • 24.99$ • 19.85£

23.76€ • 24.99$ • 19.85£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 08-22 ianuarie 25

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375711152

ISBN-10: 0375711155

Pagini: 61

Dimensiuni: 150 x 213 x 7 mm

Greutate: 0.14 kg

Editura: Knopf Publishing Group

ISBN-10: 0375711155

Pagini: 61

Dimensiuni: 150 x 213 x 7 mm

Greutate: 0.14 kg

Editura: Knopf Publishing Group

Notă biografică

Dan Chiasson was born in Burlington, Vermont, and was educated at Amherst College and Harvard University, where he completed a Ph.D. in English. His first book of poems, The Afterlife of Objects appeared in 2002. A widely published literary critic, Chiasson is the author of One Kind of Everything:Poem and Person in Contemporary America. He is the recipient of a Pushcart Prize and a Whiting Writers’ Award, and teaches at Amherst and Wellesley colleges. He lives in Sherborn, Massachusetts.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

LOVE SONG (SMELT)

When I say 'you' in my poems, I mean you.

I know it’s weird: we barely met.

You must hear this all the time, being you.

That night we were at opposite ends of

the long table, after the pungent

Russian condiments, the carafes of tarragon vodka,

the chafing dishes full of boiled smelts

I was a little drunk: after you left,

I ate the last smelt off your dirty plate.

THE SUN

There is one mind in all of us, one soul,

who parches the soil in some nations

but in others hides perpetually behind a veil;

he spills light everywhere, here he spilled

some on my tie, but it dried before dinner ended.

He is in charge of darkness also, also

in charge of crime, in charge of the imagination.

People fucking flick him off and on,

off and on, with their eyelids as they ascertain

with their eyes their love’s sincerity.

He makes the stars disappear, but he makes

small stars everywhere, on the hoods of cars,

in the compound eyes of skyscrapers or in the eyes

of sighing lovers bored with one another.

Onto the surface of the world he stamps

all plants and animals. They are not gods

but he made us worshippers of every

bramble toad, black chive, we find.

In Idaho there is a desert cricket that makes

a clocklike tick-tick when he flies, but he

is not a god. The only god is the sun,

our mind–master of all crickets and clocks.

THE ELEPHANT

How to explain my heroic courtesy? I feel

that my body was inflated by a mischievous boy.

Once I was the size of a falcon, the size of a lion,

once I was not the elephant I find I am.

My pelt sags, and my master scolds me for a botched

trick. I practiced it all night in my tent, so I was

somewhat sleepy. People connect me with sadness

and, often, rationality. Randall Jarrell compared me

to Wallace Stevens, the American poet. I can see it

in the lumbering tercets, but in my mind

I am more like Eliot, a man of Europe, a man

of cultivation. Anyone so ceremonious suffers

breakdowns. I do not like the spectacular experiments

with balance, the high-wire act and cones.

We elephants are images of humility, as when we

undertake our melancholy migrations to die.

Did you know, though, that elephants were taught

to write the Greek alphabet with their hooves?

Worn out by suffering, we lie on our great backs,

tossing grass up to heaven–as a distraction, not a prayer.

That’s not humility you see on our long final journeys:

it’s procrastination. It hurts my heavy body to lie down.

From the Hardcover edition.

When I say 'you' in my poems, I mean you.

I know it’s weird: we barely met.

You must hear this all the time, being you.

That night we were at opposite ends of

the long table, after the pungent

Russian condiments, the carafes of tarragon vodka,

the chafing dishes full of boiled smelts

I was a little drunk: after you left,

I ate the last smelt off your dirty plate.

THE SUN

There is one mind in all of us, one soul,

who parches the soil in some nations

but in others hides perpetually behind a veil;

he spills light everywhere, here he spilled

some on my tie, but it dried before dinner ended.

He is in charge of darkness also, also

in charge of crime, in charge of the imagination.

People fucking flick him off and on,

off and on, with their eyelids as they ascertain

with their eyes their love’s sincerity.

He makes the stars disappear, but he makes

small stars everywhere, on the hoods of cars,

in the compound eyes of skyscrapers or in the eyes

of sighing lovers bored with one another.

Onto the surface of the world he stamps

all plants and animals. They are not gods

but he made us worshippers of every

bramble toad, black chive, we find.

In Idaho there is a desert cricket that makes

a clocklike tick-tick when he flies, but he

is not a god. The only god is the sun,

our mind–master of all crickets and clocks.

THE ELEPHANT

How to explain my heroic courtesy? I feel

that my body was inflated by a mischievous boy.

Once I was the size of a falcon, the size of a lion,

once I was not the elephant I find I am.

My pelt sags, and my master scolds me for a botched

trick. I practiced it all night in my tent, so I was

somewhat sleepy. People connect me with sadness

and, often, rationality. Randall Jarrell compared me

to Wallace Stevens, the American poet. I can see it

in the lumbering tercets, but in my mind

I am more like Eliot, a man of Europe, a man

of cultivation. Anyone so ceremonious suffers

breakdowns. I do not like the spectacular experiments

with balance, the high-wire act and cones.

We elephants are images of humility, as when we

undertake our melancholy migrations to die.

Did you know, though, that elephants were taught

to write the Greek alphabet with their hooves?

Worn out by suffering, we lie on our great backs,

tossing grass up to heaven–as a distraction, not a prayer.

That’s not humility you see on our long final journeys:

it’s procrastination. It hurts my heavy body to lie down.

From the Hardcover edition.

Premii

- Massachusetts Book Award (MassBook) Honor Book, 2006