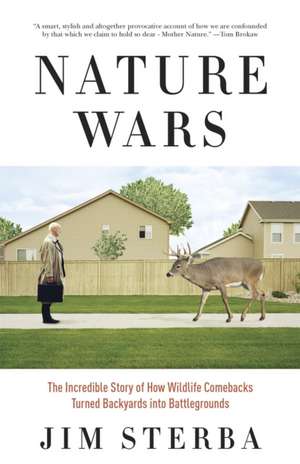

Nature Wars: The Incredible Story of How Wildlife Comebacks Turned Backyards Into Battlegrounds

Autor Jim Sterbaen Limba Engleză Paperback – 11 noi 2013

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

L.A. Times Book Prize (2012)

For 400 years, explorers, traders, and settlers plundered North American wildlife and forests in an escalating rampage that culminated in the late 19th century’s “era of extermination.” By 1900, populations of many wild animals and birds had been reduced to isolated remnants or threatened with extinction, and worry mounted that we were running out of trees. Then, in the 20th century, an incredible turnaround took place. Conservationists outlawed commercial hunting, created wildlife sanctuaries, transplanted isolated species to restored habitats and imposed regulations on hunters and trappers. Over decades, they slowly nursed many wild populations back to health.

But after the Second World War something happened that conservationists hadn’t foreseen: sprawl. People moved first into suburbs on urban edges, and then kept moving out across a landscape once occupied by family farms. By 2000, a majority of Americans lived in neither cities nor country but in that vast in-between. Much of sprawl has plenty of trees and its human residents offer up more and better amenities than many wild creatures can find in the wild: plenty of food, water, hiding places, and protection from predators with guns. The result is a mix of people and wildlife that should be an animal-lover’s dream-come-true but often turns into a sprawl-dweller’s nightmare.

Nature Wars offers an eye-opening look at how Americans lost touch with the natural landscape, spending 90 percent of their time indoors where nature arrives via television, films and digital screens in which wild creatures often behave like people or cuddly pets. All the while our well-meaning efforts to protect animals allowed wild populations to burgeon out of control, causing damage costing billions, degrading ecosystems, and touching off disputes that polarized communities, setting neighbor against neighbor. Deeply researched, eloquently written, counterintuitive and often humorous Nature Wars will be the definitive book on how we created this unintended mess.

Preț: 113.97 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 171

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.82€ • 23.70$ • 18.34£

21.82€ • 23.70$ • 18.34£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307341976

ISBN-10: 0307341976

Pagini: 343

Dimensiuni: 133 x 205 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0307341976

Pagini: 343

Dimensiuni: 133 x 205 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

JIM STERBA has been a foreign correspondent and national affairs reporter for more than four decades for the Wall Street Journal and New York Times. He is the author of Frankie’s Place: A Love Story, about summers in Maine with his wife, the author Frances FitzGerald.

Extras

Chapter One

The Spruce Illusion

Water rushed below me. I could hear it but I couldn’t see it. I was standing on a large granite stone eating an apple and swatting mosquitoes in the morning sun. The stone sat beside an asphalt road that marked the boundary of Acadia National Park. Before me was parkland. Directly in front of me, flanked by trees, was a small clearing covered with grapevines, their bright green leaves straining up toward the sun. The grapes covered the clearing like a blanket, and along its edges they had climbed up bushes and trees, curtaining them with vines and leaves. I stepped off the stone and down an embankment into the grapes and toward the noise. I bent down and pulled the interwoven vines apart with both hands, creating a small opening. Through it, I could see whitewater coursing down a brook bed, whooshing in little waterfalls over rounded stones and into a culvert under the road.

The covered brook and smothered trees so captured my attention that I didn’t realize what the grapes were trying to tell me. The grapes looked unnatural, so out of place in a northern evergreen forest that I thought of them as intruders, and with each morning jog to the clearing the urge in me grew to clear away some of them so I could see the wonderful brook. I worried about a magnificent old birch tree on the edge of the meadow that the vines had climbed and appeared to be strangling. Three vines an inch thick hung from the birch like jungle swings, and eighty feet above, grape leaves spread across the birch’s crown, soaking up its sunlight.

One morning I grabbed some long-handled pruning shears and jogged off to the clearing. I made my way down to the old birch and snipped the three vines. Their lower strands fell to the ground. Three upper strands hung straight, disconnected from their circulatory lifelines. Deprived of nutrient flows, they would shrivel and die. I had liberated the old birch. I felt a surge of pride and decided, right then, to go to war with the grapes. They were feral grapes, I thought, just like once-domesticated pigs or cats that had gone wild and multiplied on the landscape. I vowed to save all the surrounding trees from their deadly embrace and to uncover the brook for all to see. I was doing Acadia Park a favor, an unofficial volunteer working to save native species of trees, bushes, and plants from these alien invaders. I was helping to restore the park’s wild state, to re-create in this one little clearing what Acadia and other national parks were supposed to be: natural landscapes.

This rationale propelled me morning after morning into battle with the grapes. After liberating the old birch, I cut vines that had climbed up every other tree around the edge of the meadow. Then I uncovered the brook. This wasn’t easy because below the blanket of vines and leaves the grapes had formed root systems that crisscrossed each other in layers that resembled underground woven mats. Yanking on these roots caused some painful back strains and sore shoulders. The roots were tenacious. One morning I pulled on a dead tree branch hidden under some vines and a swarm of yellow jacket wasps attacked me, inflicting eight painful stings as I fled up to the road, the wasps in hot pursuit. Sometimes bikers pedaling along the road would spot me knee deep in grapevines and wave. Likewise, joggers and walkers would cast a curious glance and nod. Cars and trucks passed by all the time, but they were going too fast to catch more than a glimpse. I had no idea what these people thought. Perhaps they saw in my struggle with the grapes the quixotic quest of a madman best left in solitary derangement. I had no idea that I was committing a federal crime punishable by up to six months in prison.1

Exploring the woods around the grapes, I found old bottles, broken dinner plates, slabs of concrete, and stone walls. One morning I unearthed half of a rusty 1927 Maine automobile license plate. This was a thrilling discovery because it was the first bit of evidence I had of the age of what I had come to think of as my personal archaeological site, with mysteries to uncover, artifacts to find, and stories to decode if I could only discover and unravel them. One day at the village library, I discovered an old island map that listed the land around the grapes as belonging to a “John Brown.” My ruins were the old Brown family farm.

One day at the post office I asked Linda Hamor, the postmistress who knew everyone on the island and pretty much everything that had happened on it since the last Ice Age, who might know about the Brown farm. “Call George Peckham,” she said.

George Peckham, a seventy-eight-year-old retired engineer, had grown up on the island and now lived a quarter mile up the road from the grapes with his wife, Marion. He offered me a tour. The ruins were overgrown with big old trees. “I’d guess that ash there is at least seventy-five years old,” he said. Then he added something startling.

“Except for a couple trees in front, this was all cleared land when I was a kid--pasture and hayfields. It was clear enough for a small traveling carnival to set up every summer. And I remember coming here with my mother to pick wild strawberries. Over that way was Murphy’s gravel operation--there were big open pits.” Now it was thick forest.

At the archives of Acadia National Park, Mike Blaney and Brooke Childrey helped me find a land deed that included the Brown property. It began:

“History of this Parcel from the grant of Louis XIV, King of France, to the ownership of the estate of William Bingham . . .” It listed owners of the property over 241 years. Beginning in 1845, John Brown and his descendants operated a small subsistence farm, gravel pit, and granite quarry for nearly a century. In 1947 the family sold their holdings to John D. Rockefeller Jr., who in 1961 donated the land to the park. By the time I arrived on the scene, the forest had swallowed up the Brown farm so completely that passersby got no glimpse of the ruins within. The only hint of their existence was the grapevines, which clung to their clearing, tenaciously fending off the trees. It came as a shock when I finally realized what the grapes were trying to tell me: “We were here first.” The trees were the newcomers. The grapes were a remnant of a very different civilization that had existed not that long ago. They were like a hand reaching out of a grave in a last, desperate signal of an old way of life about to be snuffed out by the new forest.

Mount Desert looks as if it is very much part of the “North Woods”--a thick forest of evergreens interspersed with mixed hardwoods and dotted with ponds and cedar swamps, with villages, cottages, boatyards, and lobster pounds perched along a rocky seashore. Visitors can drive or climb to the summit of Cadillac Mountain, at 1,530 feet above sea level the highest point on the island, and look out upon a landscape created by glaciers that advanced and receded for a million years. Like a sculptor with chisels and sandpaper, the glacial ice cut and smoothed bedrock, creating twenty-six mountains of pink granite arranged side by side, north to south, many elongated like baguettes of French bread. The mountains, some of them bald on top, are cloaked in white and red spruce trees, balsam fir, white hemlock, and red and white pines, and are splotched with a mix of hardwoods, mainly oak, maple, and birch. The ice created a fjord, seven miles long, up the middle of the island, and gouged out other valleys that contain lakes, ponds, bogs, and dense cedar swamps. People are concentrated along the island’s coastal fringes. There, too, are the commercial trappings of a tourist industry fed mainly by Acadia National Park, the island’s primary attraction.

The island and the park attract almost 3 million visitors annually. Guidebooks say that at 108 square miles, Mount Desert is the third-largest island off the continental United States, after Long Island and Martha’s Vineyard, and, with its mountains seeming to lurch up out of the sea, it is certainly the most physically arresting of the three. For newcomers and visitors, it is easy to find here confirmation that if people just leave nature alone it will be fine. It is easy to imagine Indians and then Europeans discovering a pristine natural wilderness so beautiful that they made up their minds in turn to save it from the despoliations of man. But such imaginings would be wrong. Only small patches of the island were saved more or less in their natural state. Today what visitors see is a North Woods forest. What they are looking at, however, is natural beauty re-created, protected, and managed by man--a kind of “wilderness” theme park rebuilt by nature under human supervision.

Newcomers like me had difficulty believing that in 1880 this island was a pastoral countryside of hay meadows, livestock pastures and cropland, trees here and there, and forest hugging the steep sides of mountains off in the distance. It was hard to imagine bustling hubs where the commerce of logging, fishing, shipbuilding, and milling had taken place; villages with blacksmiths, shoemakers, wool carders, shingle makers, sawyers, and carpenters; the storefronts of merchants; factories producing lumber, barrels, ice, bricks, stones, and salted fish for market; and wharves where ships loaded materials for export and unloaded goods from afar. But that’s what Mount Desert looked like after the Civil War and well into the twentieth century.

Old--timers like George Peckham fondly recounted the days when the island had been much more manicured and refined. When Peckham was born in 1927, Mount Desert was a radically different place. Much of the island--that is, land flat enough and with soil enough to farm--had been cleared of trees by the late nineteenth century. The trees were used for fuel and lumber or were simply burned to get them out of the way for pasture, hay, and cropland. The lowland landscape and the patchwork of family farms and homesteads that occupied it were still very much in evidence when Peckham was growing up, although some of that farm acreage had already been bought up, given to Acadia National Park, and left to the trees to take back. Peckham grew up in the tail end of an era in which well-heeled vacationers turned the island into one of society’s most fashionable resorts. The island’s villages--Bar Harbor, Northeast Harbor, Southwest Harbor among them--bustled in the summer with people “from away.”

“When I was growing up, this island was more civilized than it is now,” he told me. “Northeast Harbor was booming back then. It had four garages for cars, and lots of chauffeurs, butlers, and cooks. It had four hotels, six grocery stores, two drugstores, a high school, and a summer theater. The whole island was more developed and less wild than it is now.”

Mount Desert Island has been under human supervision for almost two thousand years. Scholars don’t know exactly when Indians first arrived (graves dating back to 3000 B.C. have been found elsewhere on the Maine coast), but they are believed to have established their first settlement around 1000 B.C. at the west entrance to Somes Sound, at a place now called Fernald Point--a gently sloping hillside, with freshwater springs and protected coves. They used it and a place now called Manchester Point across the sound off and on for the next twenty-six centuries, coming and going with the seasons. Because they were hunter-gatherers and their populations were small, these people managed the land and waters of Mount Desert with a light touch--but they did manage them for their own purposes.

The first Europeans to arrive in the Gulf of Maine in the 1490s were cod fishermen--mainly Bretons, Basques, and Portuguese. Looking for fresh water and places to dry their fish, they came ashore and met the local Indians. These visits evolved into barter trade: fur garments and freshly killed meat, for example, for cloth and small metal tools. Explorers and traders followed, exchanging manufactured goods for Indian furs, mainly beaver, but for Europeans in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries Maine was a cod-fishing paradise. By the 1620s, hundreds of fishing vessels were sailing annually from European posts to catch cod in the Gulf of Maine.

Europeans broke ground on Mount Desert in 1613, when the first settlers--forty-eight Frenchmen led by a Jesuit priest named Father Pierre Biard--arrived at Fernald Point and decided, among other survival tasks, to try a little farming. Long before their crops could come in, however, they were discovered, captured, and driven off by an English privateer based in Virginia named Captain Samuel Argall. His job was to expel all Frenchmen he found along the coast.2 It would take another 148 years for farming to be taken up in earnest on the island, this time by the English--and only after the French and Indian Wars had finally sputtered to an end. The transformation of Mount Desert into a working landscape began in the fall of 1761, when a twenty-nine-year-old cooper named Abraham Somes arrived from Gloucester, Massachusetts, and took up residence at the north end of the fjord that would be named in his honor.

Over the next 150 years, settlers, fishermen, loggers, farmers, shipbuilders, and ice and granite cutters would exploit the landscape, eventually stripping away the trees on virtually all the land that was flat enough to farm. Trees on mountainsides too steep for farming and too far from water-powered sawmills were spared--for the time being. But the loggers were rapacious. They moved rapidly across the island, cutting roads in the woods, hauling out trees, and leaving brush to dry and catch fire.

1. I had violated part 2 (Resource Protection, Public Use and Recreation) of the general Federal Code provisions governing the National Park Service; specifically section 2.1 (Preservation of Natural, Cultural and Archeological Resources), subsection (a): “Except as otherwise provided in this chapter, the following is prohibited: (1): Possessing, destroying, injuring, defacing, removing, digging, or disturbing from its natural state: (ii): Plants or the parts or products thereof.” The penalties section of this statute reads: “(a) A person convicted of violating a provision of the regulations . . . of this section shall be punished by a fine as provided by law, or by imprisonment not exceeding 6 months, or both.”

2. Earlier that year in Virginia, Captain Argall kidnapped Pocahontas, the seventeen-year-old daughter of the Potomac chief, Powhatan, to exchange for English captives, property, and food. Six years earlier Pocahontas had “rescued” Captain John Smith, leader of the Jamestown Colony, from her father.

The Spruce Illusion

Water rushed below me. I could hear it but I couldn’t see it. I was standing on a large granite stone eating an apple and swatting mosquitoes in the morning sun. The stone sat beside an asphalt road that marked the boundary of Acadia National Park. Before me was parkland. Directly in front of me, flanked by trees, was a small clearing covered with grapevines, their bright green leaves straining up toward the sun. The grapes covered the clearing like a blanket, and along its edges they had climbed up bushes and trees, curtaining them with vines and leaves. I stepped off the stone and down an embankment into the grapes and toward the noise. I bent down and pulled the interwoven vines apart with both hands, creating a small opening. Through it, I could see whitewater coursing down a brook bed, whooshing in little waterfalls over rounded stones and into a culvert under the road.

The covered brook and smothered trees so captured my attention that I didn’t realize what the grapes were trying to tell me. The grapes looked unnatural, so out of place in a northern evergreen forest that I thought of them as intruders, and with each morning jog to the clearing the urge in me grew to clear away some of them so I could see the wonderful brook. I worried about a magnificent old birch tree on the edge of the meadow that the vines had climbed and appeared to be strangling. Three vines an inch thick hung from the birch like jungle swings, and eighty feet above, grape leaves spread across the birch’s crown, soaking up its sunlight.

One morning I grabbed some long-handled pruning shears and jogged off to the clearing. I made my way down to the old birch and snipped the three vines. Their lower strands fell to the ground. Three upper strands hung straight, disconnected from their circulatory lifelines. Deprived of nutrient flows, they would shrivel and die. I had liberated the old birch. I felt a surge of pride and decided, right then, to go to war with the grapes. They were feral grapes, I thought, just like once-domesticated pigs or cats that had gone wild and multiplied on the landscape. I vowed to save all the surrounding trees from their deadly embrace and to uncover the brook for all to see. I was doing Acadia Park a favor, an unofficial volunteer working to save native species of trees, bushes, and plants from these alien invaders. I was helping to restore the park’s wild state, to re-create in this one little clearing what Acadia and other national parks were supposed to be: natural landscapes.

This rationale propelled me morning after morning into battle with the grapes. After liberating the old birch, I cut vines that had climbed up every other tree around the edge of the meadow. Then I uncovered the brook. This wasn’t easy because below the blanket of vines and leaves the grapes had formed root systems that crisscrossed each other in layers that resembled underground woven mats. Yanking on these roots caused some painful back strains and sore shoulders. The roots were tenacious. One morning I pulled on a dead tree branch hidden under some vines and a swarm of yellow jacket wasps attacked me, inflicting eight painful stings as I fled up to the road, the wasps in hot pursuit. Sometimes bikers pedaling along the road would spot me knee deep in grapevines and wave. Likewise, joggers and walkers would cast a curious glance and nod. Cars and trucks passed by all the time, but they were going too fast to catch more than a glimpse. I had no idea what these people thought. Perhaps they saw in my struggle with the grapes the quixotic quest of a madman best left in solitary derangement. I had no idea that I was committing a federal crime punishable by up to six months in prison.1

Exploring the woods around the grapes, I found old bottles, broken dinner plates, slabs of concrete, and stone walls. One morning I unearthed half of a rusty 1927 Maine automobile license plate. This was a thrilling discovery because it was the first bit of evidence I had of the age of what I had come to think of as my personal archaeological site, with mysteries to uncover, artifacts to find, and stories to decode if I could only discover and unravel them. One day at the village library, I discovered an old island map that listed the land around the grapes as belonging to a “John Brown.” My ruins were the old Brown family farm.

One day at the post office I asked Linda Hamor, the postmistress who knew everyone on the island and pretty much everything that had happened on it since the last Ice Age, who might know about the Brown farm. “Call George Peckham,” she said.

George Peckham, a seventy-eight-year-old retired engineer, had grown up on the island and now lived a quarter mile up the road from the grapes with his wife, Marion. He offered me a tour. The ruins were overgrown with big old trees. “I’d guess that ash there is at least seventy-five years old,” he said. Then he added something startling.

“Except for a couple trees in front, this was all cleared land when I was a kid--pasture and hayfields. It was clear enough for a small traveling carnival to set up every summer. And I remember coming here with my mother to pick wild strawberries. Over that way was Murphy’s gravel operation--there were big open pits.” Now it was thick forest.

At the archives of Acadia National Park, Mike Blaney and Brooke Childrey helped me find a land deed that included the Brown property. It began:

“History of this Parcel from the grant of Louis XIV, King of France, to the ownership of the estate of William Bingham . . .” It listed owners of the property over 241 years. Beginning in 1845, John Brown and his descendants operated a small subsistence farm, gravel pit, and granite quarry for nearly a century. In 1947 the family sold their holdings to John D. Rockefeller Jr., who in 1961 donated the land to the park. By the time I arrived on the scene, the forest had swallowed up the Brown farm so completely that passersby got no glimpse of the ruins within. The only hint of their existence was the grapevines, which clung to their clearing, tenaciously fending off the trees. It came as a shock when I finally realized what the grapes were trying to tell me: “We were here first.” The trees were the newcomers. The grapes were a remnant of a very different civilization that had existed not that long ago. They were like a hand reaching out of a grave in a last, desperate signal of an old way of life about to be snuffed out by the new forest.

Mount Desert looks as if it is very much part of the “North Woods”--a thick forest of evergreens interspersed with mixed hardwoods and dotted with ponds and cedar swamps, with villages, cottages, boatyards, and lobster pounds perched along a rocky seashore. Visitors can drive or climb to the summit of Cadillac Mountain, at 1,530 feet above sea level the highest point on the island, and look out upon a landscape created by glaciers that advanced and receded for a million years. Like a sculptor with chisels and sandpaper, the glacial ice cut and smoothed bedrock, creating twenty-six mountains of pink granite arranged side by side, north to south, many elongated like baguettes of French bread. The mountains, some of them bald on top, are cloaked in white and red spruce trees, balsam fir, white hemlock, and red and white pines, and are splotched with a mix of hardwoods, mainly oak, maple, and birch. The ice created a fjord, seven miles long, up the middle of the island, and gouged out other valleys that contain lakes, ponds, bogs, and dense cedar swamps. People are concentrated along the island’s coastal fringes. There, too, are the commercial trappings of a tourist industry fed mainly by Acadia National Park, the island’s primary attraction.

The island and the park attract almost 3 million visitors annually. Guidebooks say that at 108 square miles, Mount Desert is the third-largest island off the continental United States, after Long Island and Martha’s Vineyard, and, with its mountains seeming to lurch up out of the sea, it is certainly the most physically arresting of the three. For newcomers and visitors, it is easy to find here confirmation that if people just leave nature alone it will be fine. It is easy to imagine Indians and then Europeans discovering a pristine natural wilderness so beautiful that they made up their minds in turn to save it from the despoliations of man. But such imaginings would be wrong. Only small patches of the island were saved more or less in their natural state. Today what visitors see is a North Woods forest. What they are looking at, however, is natural beauty re-created, protected, and managed by man--a kind of “wilderness” theme park rebuilt by nature under human supervision.

Newcomers like me had difficulty believing that in 1880 this island was a pastoral countryside of hay meadows, livestock pastures and cropland, trees here and there, and forest hugging the steep sides of mountains off in the distance. It was hard to imagine bustling hubs where the commerce of logging, fishing, shipbuilding, and milling had taken place; villages with blacksmiths, shoemakers, wool carders, shingle makers, sawyers, and carpenters; the storefronts of merchants; factories producing lumber, barrels, ice, bricks, stones, and salted fish for market; and wharves where ships loaded materials for export and unloaded goods from afar. But that’s what Mount Desert looked like after the Civil War and well into the twentieth century.

Old--timers like George Peckham fondly recounted the days when the island had been much more manicured and refined. When Peckham was born in 1927, Mount Desert was a radically different place. Much of the island--that is, land flat enough and with soil enough to farm--had been cleared of trees by the late nineteenth century. The trees were used for fuel and lumber or were simply burned to get them out of the way for pasture, hay, and cropland. The lowland landscape and the patchwork of family farms and homesteads that occupied it were still very much in evidence when Peckham was growing up, although some of that farm acreage had already been bought up, given to Acadia National Park, and left to the trees to take back. Peckham grew up in the tail end of an era in which well-heeled vacationers turned the island into one of society’s most fashionable resorts. The island’s villages--Bar Harbor, Northeast Harbor, Southwest Harbor among them--bustled in the summer with people “from away.”

“When I was growing up, this island was more civilized than it is now,” he told me. “Northeast Harbor was booming back then. It had four garages for cars, and lots of chauffeurs, butlers, and cooks. It had four hotels, six grocery stores, two drugstores, a high school, and a summer theater. The whole island was more developed and less wild than it is now.”

Mount Desert Island has been under human supervision for almost two thousand years. Scholars don’t know exactly when Indians first arrived (graves dating back to 3000 B.C. have been found elsewhere on the Maine coast), but they are believed to have established their first settlement around 1000 B.C. at the west entrance to Somes Sound, at a place now called Fernald Point--a gently sloping hillside, with freshwater springs and protected coves. They used it and a place now called Manchester Point across the sound off and on for the next twenty-six centuries, coming and going with the seasons. Because they were hunter-gatherers and their populations were small, these people managed the land and waters of Mount Desert with a light touch--but they did manage them for their own purposes.

The first Europeans to arrive in the Gulf of Maine in the 1490s were cod fishermen--mainly Bretons, Basques, and Portuguese. Looking for fresh water and places to dry their fish, they came ashore and met the local Indians. These visits evolved into barter trade: fur garments and freshly killed meat, for example, for cloth and small metal tools. Explorers and traders followed, exchanging manufactured goods for Indian furs, mainly beaver, but for Europeans in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries Maine was a cod-fishing paradise. By the 1620s, hundreds of fishing vessels were sailing annually from European posts to catch cod in the Gulf of Maine.

Europeans broke ground on Mount Desert in 1613, when the first settlers--forty-eight Frenchmen led by a Jesuit priest named Father Pierre Biard--arrived at Fernald Point and decided, among other survival tasks, to try a little farming. Long before their crops could come in, however, they were discovered, captured, and driven off by an English privateer based in Virginia named Captain Samuel Argall. His job was to expel all Frenchmen he found along the coast.2 It would take another 148 years for farming to be taken up in earnest on the island, this time by the English--and only after the French and Indian Wars had finally sputtered to an end. The transformation of Mount Desert into a working landscape began in the fall of 1761, when a twenty-nine-year-old cooper named Abraham Somes arrived from Gloucester, Massachusetts, and took up residence at the north end of the fjord that would be named in his honor.

Over the next 150 years, settlers, fishermen, loggers, farmers, shipbuilders, and ice and granite cutters would exploit the landscape, eventually stripping away the trees on virtually all the land that was flat enough to farm. Trees on mountainsides too steep for farming and too far from water-powered sawmills were spared--for the time being. But the loggers were rapacious. They moved rapidly across the island, cutting roads in the woods, hauling out trees, and leaving brush to dry and catch fire.

1. I had violated part 2 (Resource Protection, Public Use and Recreation) of the general Federal Code provisions governing the National Park Service; specifically section 2.1 (Preservation of Natural, Cultural and Archeological Resources), subsection (a): “Except as otherwise provided in this chapter, the following is prohibited: (1): Possessing, destroying, injuring, defacing, removing, digging, or disturbing from its natural state: (ii): Plants or the parts or products thereof.” The penalties section of this statute reads: “(a) A person convicted of violating a provision of the regulations . . . of this section shall be punished by a fine as provided by law, or by imprisonment not exceeding 6 months, or both.”

2. Earlier that year in Virginia, Captain Argall kidnapped Pocahontas, the seventeen-year-old daughter of the Potomac chief, Powhatan, to exchange for English captives, property, and food. Six years earlier Pocahontas had “rescued” Captain John Smith, leader of the Jamestown Colony, from her father.

Recenzii

"Smart and provocative...Nature Wars is a counterintuitive take on a social problem, and the tone is knowing and smart, not sarcastic or snide." - Chicago Tribune

"[A] sweeping and thoughtful work... there's a lot in Nature Wars for the reasoned and concerned human to learn about the changing natural landscape...[Sterba] paints a vivid and memorable portrait of these new eco systems, where only one, plentiful species is capable of bringing balance and harmony among living things: homo sapiens." -LA Times

"Fascinating...Sterba portrays the resulting conflicts not only between people and animals but also between hunters and activists, government officials and residents, and any number of other factions." -Washington Post

"Written with considerable charm and more wit than commonly found in works that deal with ecosystems, [Nature Wars] includes extensive and often entertaining treatments of such common nuisances as beavers, Canada geese, and feral cats...For the denatured reader, there is a wealth of useful statistics."-New York Review of Books

"While advancing his brief that mankind has to do more to intervene as managers in the natural process, Sterba also ably documents how we influence wildlife without really trying or realizing it." -Christian Science Monitor

"Jim Sterba’s Nature Wars chronicles the dilemmas created by the resurgence of wildlife populations in much of the eastern United States…[A] thoughtful text." -Seattle Times

"[Sterba] makes a provocative, controversial, but quite compelling case that we should not - and cannot - opt out of active management and stewardship of wildlife." -Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

"

"In Nature Wars, Sterba, an award-winning journalist, examines how modern society is fighting a new war against the wildlife and nature that surround us...an interesting look at how man's attempt to control nature has created even more problems...Thoroughly researched." -Deseret News

"In his book Nature Wars, [Sterba] highlights nature's perils... nature has never been as idyllic as we think."- Emma Bryce, Discover Magazine

"This is an excellent introduction to a “problem” that is often one of human perception." - Booklist, starred review

"Jim Sterba employs humor and an eye for the absurd to document the sometimes bizarre conflicts that arise as a consequence of America's transformed relationship with nature... An eye-opening take on how romantic sentimentalism about nature can have destructive consequences." - Kirkus, starred review

"Sterba provocatively and persuasively argues that just at the moment when humankind has distanced itself irrevocably from nature, its behavior patterns have put people in conflict with a natural world that they don’t know how to deal with...A valuable counternarrative to the mainstream view of nature-human interaction." - Publisher's Weekly

“In this elegant and compelling tour of America’s mutating connections with its land and wildlife, Jim Sterba uses wit and insight to reveal new and unintended consequences of human sprawl and the ways in which they have shaped today’s relationships with Nature.” -John H Adams , Founding Director , Natural Resources Defense Council

“It's a jungle out there - and we're living in it. Jim Sterba's Nature Wars is a smart, stylish and altogether provocative account of how we are confounded by that which we claim to hold so dear - Mother Nature and all her creatures moving in right next door.” --Tom Brokaw

“Jim Sterba describes a cockeyed country whose denizens spend billions to imitate "nature" in their own small domains, little realizing that their excess creates an environment to which other species are fatefully drawn in increasing, sometimes alarming numbers; that they themselves are the creatures who throw this shared habitat out of whack. An unusual feat of deep and sustained reporting, Nature Wars is full of surprises and marked, from first page to last, by uncommon sense, graceful writing and precious wit.” ߝ Joseph Lelyveld, author of Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle with India

“Quite unintentionally and with little awareness by its inhabitants, over the past century the Eastern United States has become one of the most heavily forested and densely populated regions in world history. Nature Wars explores this marvelous story of environmental recovery and the opportunities and challenges that it brings to its residents and the entire globe in fascinating detail and with great insight by Jim Sterba. This is a great book and a story with lessons for us all.” ߝ David Foster, Ecologist and Director of the Harvard Forest, Harvard University

“If there is one lesson to be learned from Jim Sterba’s book, it is: Be careful what you wish for. Having decimated our planet’s natural state, we are blithely over-compensating, over ߝcorrecting and overturning the balance of nature yet again. Nature, as seen by most of us through a double glazed picture window revealing a manicured lawn….but what’s that moose being chased by a coyote being chased by a black bear, doing there? Read Nature Wars and weep. Or at least, stop and think.” ߝ Morley Safer

"In Nature Wars, Jim Sterba lays out battle lines that emerged after populations of species that declined to near-extinction by the end of the 19th century came roaring back...This book is sure to initiate discussion about an issue that seems likely to move closer to the forefront in the years ahead." - Jerry Harkavy

"In this book, Jim Sterba has given us a fascinating, powerful, and important lesson in why we should be careful when we mess with Mother Nature.” ߝ Winston Groom, author of Forrest Gump

“At last someone’s grappling with the elephant in the room ߝ or rather the deer, the coyote, the beaver, the bear, all these damn animals crowding into our living space. Sterba’s book may strike some as observational comedy but he’s deadly serious. Every word rings true. Nature is vengeful. All I can say is, he better not take a walk in his backyard without a shotgun.” ߝ John Darnton, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author of Almost a Family

“A wonderful, thought-provoking, important book that will overturn everything you thought you knew about wildlife in America. Jim Sterba confronts the shibboleths that make man-versus-beast conflicts so vexing, divisive, and fascinatingly complex." ߝ David Baron, author of The Beast in the Garden

“It’s a truly original piece of work, often ߝ I would say ߝ inspired, told in a pitch-perfect voice, just north of sarcastic and south of appalled. At any event, a terrific read on a subject that is all around us yet largely unobserved.” Ward Just, author of Rodin’s Debutante

"Anything Jim Sterba writes is worth reading--and his latest, Nature Wars, is terrific. Sterba casts a reporter's sharp eye on a little noticed war unfolding under our noses, in our own backyards. We've messed with nature for way too long, and nature is getting even." --Joseph L. Galloway, co-author of We Were Soldiers Once...and Young and We Are Soldiers Still

“Jim Sterba has done a brilliant job explain how it happens that drivers more often than ever run into deer, wild turkeys fly into speeding car windshields and gorge on newly-planted seed corn, and why golf courses are filled with people chasing geese down the fairways with 5 irons in hand. This informative and beautifully written book gives us the effect of civilization (often well-meaning) on the natural habitat, both flora and fauna. I loved the book and learned a great deal from it.” ߝ Peter Duchin, musician and author of Ghost of Chance

"If you love animals and trees and other wonders of the natural world, this book will astonish you. Sterba's great gifts are reportorial energy, out-of-the-box thinking, and an easy, relaxed prose style that makes Nature Wars a pleasure to read, even as its counterintuitive discoveries explode on every page." --Daniel Okrent, author of Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition

“Most Americans now live not in cities but in regrown forests, among at least as many deer as when Columbus landed. Jim Sterba tells us how this came to be and why it isn’t all good. In graceful, clear-eyed prose, he explains why we need to relearn how to cut, cull and kill, to restore a more healthy balance to our environment.” ߝ Paul Steiger, Editor-in-Chief, ProPublica

"Although few of us realize it, America is at a turning point where we must rethink our most fundamental ideas about nature, animals, and how we live. Fortunately we have a wise and witty guide in Jim Sterba, whose Nature Wars is my favorite kind of read -- a book that affectionately recasts much of what we thought we knew about our nation's past and our relationship to the American wild, while at the same time revealing how intimately we ourselves are a part of nature, but in the most surprising and unexpected ways. In Sterba's hands, your everyday notions about the creatures around you -- whether pests, pets, or magnificent beasts -- will turn into entirely new ways of seeing the world." -Trevor Corson, author of The Secret Life of Lobsters and The Story of Sushi

"[A] sweeping and thoughtful work... there's a lot in Nature Wars for the reasoned and concerned human to learn about the changing natural landscape...[Sterba] paints a vivid and memorable portrait of these new eco systems, where only one, plentiful species is capable of bringing balance and harmony among living things: homo sapiens." -LA Times

"Fascinating...Sterba portrays the resulting conflicts not only between people and animals but also between hunters and activists, government officials and residents, and any number of other factions." -Washington Post

"Written with considerable charm and more wit than commonly found in works that deal with ecosystems, [Nature Wars] includes extensive and often entertaining treatments of such common nuisances as beavers, Canada geese, and feral cats...For the denatured reader, there is a wealth of useful statistics."-New York Review of Books

"While advancing his brief that mankind has to do more to intervene as managers in the natural process, Sterba also ably documents how we influence wildlife without really trying or realizing it." -Christian Science Monitor

"Jim Sterba’s Nature Wars chronicles the dilemmas created by the resurgence of wildlife populations in much of the eastern United States…[A] thoughtful text." -Seattle Times

"[Sterba] makes a provocative, controversial, but quite compelling case that we should not - and cannot - opt out of active management and stewardship of wildlife." -Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

"

"In Nature Wars, Sterba, an award-winning journalist, examines how modern society is fighting a new war against the wildlife and nature that surround us...an interesting look at how man's attempt to control nature has created even more problems...Thoroughly researched." -Deseret News

"In his book Nature Wars, [Sterba] highlights nature's perils... nature has never been as idyllic as we think."- Emma Bryce, Discover Magazine

"This is an excellent introduction to a “problem” that is often one of human perception." - Booklist, starred review

"Jim Sterba employs humor and an eye for the absurd to document the sometimes bizarre conflicts that arise as a consequence of America's transformed relationship with nature... An eye-opening take on how romantic sentimentalism about nature can have destructive consequences." - Kirkus, starred review

"Sterba provocatively and persuasively argues that just at the moment when humankind has distanced itself irrevocably from nature, its behavior patterns have put people in conflict with a natural world that they don’t know how to deal with...A valuable counternarrative to the mainstream view of nature-human interaction." - Publisher's Weekly

“In this elegant and compelling tour of America’s mutating connections with its land and wildlife, Jim Sterba uses wit and insight to reveal new and unintended consequences of human sprawl and the ways in which they have shaped today’s relationships with Nature.” -John H Adams , Founding Director , Natural Resources Defense Council

“It's a jungle out there - and we're living in it. Jim Sterba's Nature Wars is a smart, stylish and altogether provocative account of how we are confounded by that which we claim to hold so dear - Mother Nature and all her creatures moving in right next door.” --Tom Brokaw

“Jim Sterba describes a cockeyed country whose denizens spend billions to imitate "nature" in their own small domains, little realizing that their excess creates an environment to which other species are fatefully drawn in increasing, sometimes alarming numbers; that they themselves are the creatures who throw this shared habitat out of whack. An unusual feat of deep and sustained reporting, Nature Wars is full of surprises and marked, from first page to last, by uncommon sense, graceful writing and precious wit.” ߝ Joseph Lelyveld, author of Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle with India

“Quite unintentionally and with little awareness by its inhabitants, over the past century the Eastern United States has become one of the most heavily forested and densely populated regions in world history. Nature Wars explores this marvelous story of environmental recovery and the opportunities and challenges that it brings to its residents and the entire globe in fascinating detail and with great insight by Jim Sterba. This is a great book and a story with lessons for us all.” ߝ David Foster, Ecologist and Director of the Harvard Forest, Harvard University

“If there is one lesson to be learned from Jim Sterba’s book, it is: Be careful what you wish for. Having decimated our planet’s natural state, we are blithely over-compensating, over ߝcorrecting and overturning the balance of nature yet again. Nature, as seen by most of us through a double glazed picture window revealing a manicured lawn….but what’s that moose being chased by a coyote being chased by a black bear, doing there? Read Nature Wars and weep. Or at least, stop and think.” ߝ Morley Safer

"In Nature Wars, Jim Sterba lays out battle lines that emerged after populations of species that declined to near-extinction by the end of the 19th century came roaring back...This book is sure to initiate discussion about an issue that seems likely to move closer to the forefront in the years ahead." - Jerry Harkavy

"In this book, Jim Sterba has given us a fascinating, powerful, and important lesson in why we should be careful when we mess with Mother Nature.” ߝ Winston Groom, author of Forrest Gump

“At last someone’s grappling with the elephant in the room ߝ or rather the deer, the coyote, the beaver, the bear, all these damn animals crowding into our living space. Sterba’s book may strike some as observational comedy but he’s deadly serious. Every word rings true. Nature is vengeful. All I can say is, he better not take a walk in his backyard without a shotgun.” ߝ John Darnton, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author of Almost a Family

“A wonderful, thought-provoking, important book that will overturn everything you thought you knew about wildlife in America. Jim Sterba confronts the shibboleths that make man-versus-beast conflicts so vexing, divisive, and fascinatingly complex." ߝ David Baron, author of The Beast in the Garden

“It’s a truly original piece of work, often ߝ I would say ߝ inspired, told in a pitch-perfect voice, just north of sarcastic and south of appalled. At any event, a terrific read on a subject that is all around us yet largely unobserved.” Ward Just, author of Rodin’s Debutante

"Anything Jim Sterba writes is worth reading--and his latest, Nature Wars, is terrific. Sterba casts a reporter's sharp eye on a little noticed war unfolding under our noses, in our own backyards. We've messed with nature for way too long, and nature is getting even." --Joseph L. Galloway, co-author of We Were Soldiers Once...and Young and We Are Soldiers Still

“Jim Sterba has done a brilliant job explain how it happens that drivers more often than ever run into deer, wild turkeys fly into speeding car windshields and gorge on newly-planted seed corn, and why golf courses are filled with people chasing geese down the fairways with 5 irons in hand. This informative and beautifully written book gives us the effect of civilization (often well-meaning) on the natural habitat, both flora and fauna. I loved the book and learned a great deal from it.” ߝ Peter Duchin, musician and author of Ghost of Chance

"If you love animals and trees and other wonders of the natural world, this book will astonish you. Sterba's great gifts are reportorial energy, out-of-the-box thinking, and an easy, relaxed prose style that makes Nature Wars a pleasure to read, even as its counterintuitive discoveries explode on every page." --Daniel Okrent, author of Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition

“Most Americans now live not in cities but in regrown forests, among at least as many deer as when Columbus landed. Jim Sterba tells us how this came to be and why it isn’t all good. In graceful, clear-eyed prose, he explains why we need to relearn how to cut, cull and kill, to restore a more healthy balance to our environment.” ߝ Paul Steiger, Editor-in-Chief, ProPublica

"Although few of us realize it, America is at a turning point where we must rethink our most fundamental ideas about nature, animals, and how we live. Fortunately we have a wise and witty guide in Jim Sterba, whose Nature Wars is my favorite kind of read -- a book that affectionately recasts much of what we thought we knew about our nation's past and our relationship to the American wild, while at the same time revealing how intimately we ourselves are a part of nature, but in the most surprising and unexpected ways. In Sterba's hands, your everyday notions about the creatures around you -- whether pests, pets, or magnificent beasts -- will turn into entirely new ways of seeing the world." -Trevor Corson, author of The Secret Life of Lobsters and The Story of Sushi

Premii

- L.A. Times Book Prize Finalist, 2012