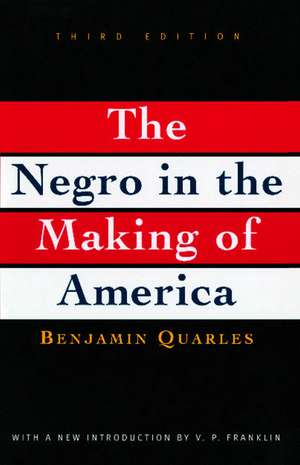

Negro in the Making of America: Third Edition Revised, Updated, and Expanded

Introducere de V.P. Franklin Autor Benjamin Quarlesen Limba Engleză Paperback – 5 feb 1996

In The Negro in the Making of America, eminent historian Benjamin Quarles provides one of the most comprehensive and readable accounts ever gathered in one volume of the role that African Americans have played in shaping the destiny of America. Starting with the arrival of the slave ships in the early 1600s and moving through the Colonial period, the Revolutionary and Civil Wars, and into the last half of the twentieth century, Quarles chronicles the sweep of events that have brought blacks and their struggle for social and economic equality to the forefront of American life.

Through compelling portraits of central political, historical, and artistic figures such as Nat Turner, Frederick Douglass, Duke Ellington, Malcolm X, and the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., Quarles illuminates the African American contributions that have enriched the cultural heritage of America. This classic history also covers black participation in politics, the rise of a black business class, and the forms of discrimination experienced by blacks in housing, employment, and the media.

Quarles's groundbreaking work not only surveys the role of black Americans as they engaged in the dual, simultaneous processes of assimilating into and transforming the culture of their country, but also, in a portrait of the white response to blacks, holds a mirror up to the deeper moral complexion of our nation's history. The restoration of this history holds a redemptive quality—one that can be used, in the author's words, as a "vehicle for present enlightenment, guidance, and enrichment."

Preț: 146.18 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 219

Preț estimativ în valută:

27.98€ • 30.40$ • 23.52£

27.98€ • 30.40$ • 23.52£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780684818887

ISBN-10: 0684818884

Pagini: 400

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Ediția:3 SUB

Editura: Touchstone Publishing

Colecția Touchstone

ISBN-10: 0684818884

Pagini: 400

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Ediția:3 SUB

Editura: Touchstone Publishing

Colecția Touchstone

Notă biografică

Benjamin Quarles was Emeritus Professor of History at Morgan State University in Baltimore and the author of many books on African American history, including Frederick Douglass, The Negro in the American Revolution, Black Abolitionists, and The Negro in the Civil War.

Extras

Chapter 1

From Africa to the New World (to 1619)

"E pluribus unum," the national motto of the United States, means "one from many." Suggested by patriots at the outbreak of the American Revolution, this motto was originally used in a political sense, to demonstrate that out of thirteen separate states one new sovereign power had come into existence. But since the time of the Revolutionary War, this Latin expression has taken on a larger meaning. It has come to suggest that America is made up of many peoples from many lands, having become, in essence, a nation of nations. One of these many groups came from the continent of Africa, a group that was numbered among the very first to arrive in the New World.

Of the varied Old World stocks that entered America, none came from as wide a geographic area as the blacks. The vast majority came from the West Coast of Africa, a 3,000-mile stretch extending from the Senegal River, downward around the huge coastal bulge, to the southern limit of present-day Portuguese Angola. A small percentage came from Mozambique and the island of Madagascar in far-away East Africa, and still fewer came from the Sudanese grasslands that bordered the Sahara.

Just as the ancestor of the American Negro came from no single region, so he was of no single tribe or physical type. The "West Coast Negro," the predominant type that came to the New World, was marked by such characteristics as tall stature, woolly hair, broad features, full lips, little growth of hair on face or body, and a skin color approaching true black. But there was no such thing as one African "race." Slave ships bound for America carried a variety of genetic stocks, from the tallish, dark-skinned Ashanti of the forest lands north of the Gold Coast to the lighter and shorter Bantu from the Congo basin. Indeed, the difficulty of generalizing about the physical characteristics of the Negroid peoples is illustrated by the Nilotics and the Pygmies, one being the tallest group in the world (averaging nearly six feet in height) and the other being the shortest (averaging less than five feet).

These varied groups had no common tongue, no "lingua Africana." Indeed, there are more than 200 distinct languages in present-day Nigeria alone. There was no such thing as "the African personality," since the varied groups differed as much in their ways of life as in the physical characteristics they exhibited and the languages they spoke.

In their political institutions, there was much diversity. "One meets in Negro Africa," wrote Maurice Delafosse, "a whole series of States, ranging from the simple isolated family to confederations of kingdoms constituting empires." In pre-European Africa innumerable village kinship groups, no larger than a clan, were completely independent in their exercise of a kind of "grass-roots" democracy. These small political systems stood in contrast to an extensive empire-state like Songhay: at the height of its power, this empire extended from Lake Chad westward to the Atlantic, covering an area as large as Europe. Its most notable ruler was Askia Mohammed I (on the throne from 1493 to 1528), whose word carried as much authority in the hinterlands as at his own palace at Gao on the central Niger.

Although there were various types of states, the fundamental unit politically, as in other ways, was the family. This was not one man's family; rather, it was a kinship group numbering in the hundreds, but called a family because it was made up of the living descendants of a common ancestor. The dominant figure in this extended family community was the patriarch, who exercised a variety of functions, acting as peacemaker, judge, administrator, and keeper of the purse. The patriarch generally sought the advice of the recognized elders.

In the immediate family the practice of plural marriage was not uncommon; one man might have more than one wife if he could afford it. As a rule, marriages were formally arranged between the families, with some form of payment -- livestock generally -- going to the bride's parents. This "brideprice" was not meant to indicate that the wife had been bought; rather, it was a means of recompensing the bride's parents for their loss.

In their ways of making a living, as in other aspects of their culture, there were regional variations among the Africans. Dwellers along the shores of the great rivers turned to fishing and boat-making. In the grasslands the economy was primarily pastoral, the chief livestock being goats, sheep, and cattle. Some occupations were widespread, among them the hunting of game and the gathering of beans, nuts, and fruits. Each village had its corps of artisans, often organized into craft guilds. This skilled-labor class embraced pottery makers, weavers, wood carvers, and iron workers.

Most of the people worked in the fields that surrounded their villages, the basic economy being agricultural. Crops were grown on plots of land cleared by fire or by the felling of trees. Securing adequate foodstuffs from the earth was not always easy, but the tillers of the soil had learned such secrets as transplanting. Most of the produce was intended for local consumption, but some of it might be destined for sale outside the village. So important was agriculture as a means of livelihood that private possession of a tract of earth was not permitted. The land was the possession of the collective group; the individual had only the right to its use, owning nothing but the crops he raised.

Like so much else in African life, the land system was tied in with the gods. Among the peoples of the West Coast, religious forces found full and varied outlets. There was a supreme deity and a host of lesser ones, the latter being identified with such natural objects as rivers and the wind. Each god had priests and "diviners" who interpreted his will. The gods did not exhaust the heavenly host; sharing their powers were innumerable spirits, some of them ancestral, but most of them inhabiting the everyday objects of the hut and field.

Filling a definite place in the religious life of the Africans were their art forms, particularly the statuettes and masks of bronze, wood, or ivory that were produced as adjuncts to the performance of religious and magical rites. This wedding of art to experience gave to African sculpture its enduring vitality; the modern critic Alain Locke viewed these carved works as technically so mature and sophisticated that they could be rated as "classic in the best sense of the word." Since art was functional, the urge to express it was deeply ingrained.

Music, too, found universal expression. Among its manifestations were complex compositions for voice, an ear for the subtlest rhythm, and the use of a wide variety of instruments, including the drum, harp, xylophone, violin, guitar, zither, and flute. Like music, the dance was legion, being performed for any number of observances and purposes. Any event worthy of notice was celebrated by rhythmic movement -- births, marriages, or death. Each dance served its own specific purpose; the fertility dance, for example, was, in essence, a prayer that the seed might take good root in the soil and grow well.

The literature produced by the Africans was primarily oral rather than written and can be classified as professional and popular. In the former, knowledge about the history, customs, and traditions of the group was transmitted by men who made a profession of memorizing. The popular literature included tales, proverbs, and riddles passed down from one generation to another, occasionally by trained narrators, but most commonly by amateur storytellers.

In summary, the Negroes who came to the New World varied widely in physical type and ways of life, but there were many common patterns of culture. Whatever the type of state, the varied groups all operated under orderly governments, with established legal codes, and under well-organized social systems. The individual might find it necessary to submerge his will into the collective will, but he shared a deep sense of group identity, a feeling of belonging. And there was ample scope for personal expression -- in crafts, in art, in worship, or in music and the dance.

African societies before the penetration of the Europeans were not backward and static, with their people living in barbarism and savagery. A more accurate view is now being unfolded by modern-day scholars in history, anthropology, archeology, and linguistics. The fruits of their researches show that the peoples of Africa from whom the American Negro is descended have made a rich contribution to the total resources of human culture.

The modern traffic in African slaves began in the mid-fifteenth century, with Portugal taking the lead. In 1441 Prince Henry the Navigator sent one of his mariners, the youthful Antonio Gonsalves, to the West Coast to obtain a cargo of skins and oils. Landing near Cape Bojador, the young captain decided that he might please his sovereign by bringing him gifts. Taking possession of some gold dust and loading ten Africans on his cockleshell, Gonsalves made his way back to Lisbon. Henry was greatly pleased by the gold and the slaves, deeming the latter of sufficient importance to send to the Pope.

In turn, the Pope conferred upon Henry the title to all lands to be discovered to the east of Cape Blanco, a point on the West Coast some 300 miles above the Senegal. Thus began a new era. With renewed vigor Portuguese seamen pressed on with their systematic exploration of the African coastline.

These pioneers found Africa to be a treasure house. It had gold, which, in addition to being valuable in itself, was indispensable as means of paying for the products they wanted from the Orient, India especially. From the West Coast, too, came pepper and elephant tusks, ivory always having a ready market in the commercial centers of the world. But the chief prize of all was the supply of slaves, which, unlike other merchandise, seemed to be inexhaustible. Within two decades after Gonsalves's voyage off Cape Bojador, the slave trade proved to be highly profitable in the European market, and within another half-century this new labor supply was finding its greatest demand in the newly discovered lands across the Atlantic. The settlements founded in America by Spain soon opened the floodgates for all the black cargoes European bottoms could carry.

With so lucrative an African trade, it was only natural that Portugal should try to shut other nations from the profits. For nearly a century she was successful; Spain, her only likely competitor during that period, was not a maritime power, preferring to stock her colonies by means of contracts (assientos) granted by the king to merchants of other countries.

But to keep other rivals away indefinitely was far beyond Portugal's power. By the latter part of the sixteenth century her monopoly was being successfully challenged by England and France, the latter almost displacing her in the Senegal and Gambia river regions during the 1570s. During the following century the African trade attracted the Dutch, Danes, Swedes, and Brandenburg Germans. By far the most formidable of these was the Dutch, who formed a West India Company in 1621 and sixteen years later seized Elmina on the Gold Coast, Portugal's strongest fortification in Africa. For the next fifty years the Hollanders were second to none in the slave-carrying trade, a position they slowly relinquished to England after 1700.

Whatever the nation, the actual operation of the slave trade was much the same. Usually the sovereign in Europe would grant a trade monopoly to a group of favored merchants, it being assumed that the privilege of foreign commerce resided in the Crown. The merchant company was thus protected against competition, at least from interlopers of their own nationality, and could proceed to stock its ships with the goods necessary for the exchange. Such goods consisted of textiles -- woolens, linens, cottons, and silks -- knives and cutlasses; firearms, powder, and shot; and iron, copper, brass, and lead in bar form for local smithies. A staple of the trade was intoxicating drink -- rum, brandy, gin, or wine. Ships also made it a point to carry a supply of trinkets -- baubles, bells, looking-glasses, bracelets, and glass beads -- which were of negligible cost and had a fascination for native chiefs.

Upon landing for the first time, the trading company made arrangements to establish a joint fort and trading station. One of the first buildings to go up would be a barracoon, a warehouse where slaves could be kept until the voyage across the Atlantic. Thus laden with goods, and with storage space to accommodate the expected human cargo, the trader was ready to do business with the native chief. The whites did not go into the interior to procure slaves; this they left to the Africans themselves. Spurred on by the desire for European goods, one tribe raided another, seized whatever captives it could, and marched them in coffles, with leather thongs around their necks, to the coastal trading centers.

Doubtless the full enormity of what they were doing did not dawn on the African chiefs. Neither intertribal warfare nor human bondage was uncommon. Indeed, from time immemorial men in Africa had become slaves by being captured in warfare, or as a punishment for crime, or because of failure to pay debts. There was, however, no stigma of inherent inferiority attached to slave status; no hard and fast color or caste hurdles prevented a former slave from becoming free and rising to a great place. Moreover, the demand for slaves had been limited. But when the European arrived, there was a great upsurge in the market for slaves, and the native chiefs were unwilling to resist the temptations of the trade. Later, when the entire West Coast had been turned into a huge slave corral, the chiefs were unable to arrest the traffic.

With a human cargo to dispose of, the native chief was ready to negotiate with the trader. Generally the latter began by offering presents to the king -- hats and bunches of beads. Then the bargaining got under way, with the Africans usually showing great shrewdness. Merchant-owner John Barbot, trading at New Calabar in 1699, gave vent to his vexation over the haggling propensities of the king's assistant Pepprell, characterizing him as being "a sharp blade, and a mighty talking black, perpetually making sly objections against something or other, and teasing us for this or that dassy, or present, as well as for drams."

Sometimes the trader might have to do business at a loss, and sometimes he had to leave empty-handed when his goods were not wanted, even though on a previous trip the identical kind of article had gone well with the same chief. But as a rule, the trader was likely to find his goods marketable. Prices varied greatly, but the average cost of a healthy male was $60 in merchandise; a woman could be bought for $15 less. Before completing the transaction, the buyer invariably took the precaution of having the slaves examined by his physician.

When enough Negroes had been procured to make a full cargo, the next step was to get them to the West Indies with the greatest possible speed. Food was stocked for crew and slaves -- yams, coarse bananas, potatoes, kidney beans, and coconuts. Then, after having been branded for identification, the blacks came aboard, climbing up the swaying rope ladders, prodded on by whips. The sexes were placed in different compartments, with the men in leg irons. The ship then hoisted anchor and started toward the West Indies, a voyage fifty days in length if all went well. This was the "Middle Passage," so called because it was the second leg in the ship's triangular journey -- home base to Africa, thence to the West Indies, and finally back to the point of original departure.

The Middle Passage has come to have a bad name, and in truth the voyage was one of incredible rigor. When in 1679 the frigate Sun of Africa made a trip from the Gold Coast to Martinique, there were only seven deaths out of a cargo of 250 slaves, but such a light loss was exceptional. On an average, the Atlantic voyage brought death to one out of every eight black passengers. A slaver was invariably trailed by a school of man-eating sharks.

A few captains were "loose packers," but the great majority were "tight packers," believing that the greater loss in life would be more than offset by the larger cargo. On their ships the space allowed a slave was confined to the amount of deck in which he could lie down, and the decks were so narrow as to permit just enough height for the slave to crawl out to the upper deck at feeding time.

Disease took its toll, especially when the ship was struck with an epidemic of scurvy or the flux. "The Negroes are so incident to the small-pox," wrote Captain Thomas Phillips of the Hannibal, "that few ships that carry them escape without it." Adding greatly to the threat of a disease outbreak was the danger that the food and water would run short.

The hazards of nature were not as vexing as the behavior of the slaves. Some committed suicide by managing to jump through the netting that had been rigged around the ship to prevent that very step. Others seemed to have lost the will to live. To guard against such suicidal melancholy, a ceremony known as "dancing the slaves" was practiced: they were forced to jump up and down to the tune of the fiddle, harp, or bagpipes. A slave who tried to go on a hunger strike was forcibly fed, by means of a "mouth-opener" containing live coals.

The most serious danger by far was that of slave mutiny, and elaborate precautions were taken to prevent uprisings. Daily searches of the slave quarters were made, and sentinels were posted at the gun room day and night. But the captain and his undermanned crew were not always able to control their cargo of blacks. So numerous were slave insurrections on the high seas that few shipowners failed to take out "revolt insurance."

But, despite all risks and dangers, the slave trade flourished. The profits were great. After taking out all expenses, including insurance payments and sales commissions, a slaving voyage was expected to make a profit of thirty cents on the dollar. Such a lucrative trade was an outgrowth of the insatiable demand for "black ivory" in the New World.

The transplanted Africans found a variety of tasks awaiting them in the lands across the Atlantic. Their service dates almost from the discovery of America, cabin boy Diego el Negro coming with Columbus on his fourth voyage in 1502. Almost without exception, every subsequent discoverer and explorer sailing for the New World from the ports of Andalusia numbered Negroes among his crew, slaves having become common in Portugal and southern Spain. When Balboa first "stared at the Pacific," he carried thirty Negroes in his train. Hernando Cortez, conqueror of Mexico, made use of slaves in hauling the artillery that terrified the Aztecs. One of the Negroes with the Cortez expedition was the sower and reaper of the first wheat crop in America. Lucas Vasquez de Ayllon, exploring the Atlantic coast regions in 1526, was one of the earliest "conquistadores" to bring Negroes into the present boundaries of the United States. Panfilo de Navaez, who hoped to rival the exploits of Cortez, and his successor, Cabeza de Vaca, depended upon slave labor in their wanderings in the waters of the Gulf of Mexico.

The most renowned of the Negroes who accompanied the Spanish pioneers was the Moroccan, Estavanico -- scout, guide, and ambassador for Navaez and Cabeza de Vaca. In March 1539, with Estavanico as guide, a party of three Spaniards and a group of Pima Indians set out in search of the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola. Estavanico never found these nonexistent places, but his travels led him to the region of the present state of New Mexico, which he was the first man to behold, except for the aborigines. Negroes could also be found with the French explorers -- in the Great Lakes area, along the Mississippi Valley, and in Louisiana.

A slave used as a guide, like Estavanico, was out of the ordinary. It was as a laborer, rather than anything else, that the Negro was needed in the New World. For the Spanish had decided quite early that Negro labor was more suitable than Indian labor. Catholic bishops like Bartholome de Las Casas and Diego de Landa developed a marked sympathy for the Indians, and hence became strong exponents of Negro slavery. In support of this stand, a theory took root that the Indian was physically far inferior to the Negro, and thus less able to stand hard labor in a hot climate.

Aside from the attitude of the bishops, there seemed to be sound ground for the preference of the Negro over the Indian. The former showed a greater resistance to the white man's diseases -- measles, yellow fever, and malaria. Moreover, the transplanted African was better able to adjust to the discipline of the plantation system, for he came from an economic order more complex than that of the Indian.

Although slaves were used in mining gold on the mainland, particularly in New Granada, it was to the West Indies that slavery and the slave trade owed their initial enormous growth. Indeed, at the close of the eighteenth century over half of the 800,000 Negroes in Spanish America were to be found in Cuba and Puerto Rico. The islands produced a variety of commodities -- indigo, coffee, cotton, tobacco, hides, and ginger -- but their mainstay was sugar. More than all other products combined, it was sugar that created the great demand for slaves in America, and it was the sugar industry that determined their geographical distribution therein. Hitherto rare in Europe, sugar now became big business, and the West Indies were commonly called the "Sugar Islands."

Sugar cane culture readily lent itself to slave labor. Its operations were not hard to learn -- clearing land, hoeing, planting, weeding, and cane cutting -- and they provided year-round employment. Moreover, slaves could be worked in large gangs, which were easily supervised.

Just as Portugal had been unable to prevent other European powers from coming to Africa, so Spain was unable to keep her rivals out of the Caribbean. By the middle of the seventeenth century the Spanish monopoly had been broken, and Denmark, Holland, and France were establishing themselves in the islands. Spain's weakening grasp became starkly apparent when England in 1655 wrested Jamaica from her. This possession soon became the chief slave market in the Western Hemisphere.

The European powers who now planted their flags in the islands found it expedient to permit independent merchants of their nationality to share in the slave traffic, which had grown too large to be handled by one company of licensees. The mother countries were quick to sense that West Indian possessions, in addition to supplying sugar, enabled them to build up their merchant shipping by furnishing a nursery for their seamen. Island possessions also created a market for their manufactures: "The Negro-Trade and the natural consequences resulting from it," wrote a contemporary Englishman, "may be justly esteemed an inexhaustible Fund of Wealth and Naval Power to this Nation."

Although many profited from the trade, the West India planter was its backbone; it was he who kept the wheels in motion by his constant seeking of more slaves. In making his purchases, the planter, or his agent, sometimes went to the mainland marts -- Cartagena, Panama, or Vera Cruz. But, as a rule, slaves could be obtained from stocks kept in West India port barracoons. Sometimes a slave-laden ship would sail into an island port and sell its cargo to a single buyer, or to multiple buyers. Less often a slaver would sail into a planter's own waters, seeking to dispose of its blacks.

Slave purchases were made at the buyer's risk. This the planter knew. And he sensed, if he did not know, that all ship captains had orders much like that issued to Anthony Overstall, commander of the Judith: "You must be mindful to have your Negroes Shaved and made Clean to look well and strike a good impression on the Buyers at whatever place you touch at."

Once the slave was purchased, it became necessary to break him in -- to accustom him to the routines of plantation slavery in a new and strange environment. In this seasoning process -- generally running to three years -- the freshly arrived blacks would be distributed among veterans, or they would be placed under special supervisors. When the slave was fully seasoned -- having learned his work assignment, become accustomed to the food and climate, learned to understand a new language, and shaken off any tendency to suicide -- he was worth twice as much as when he first landed.

The lot of the slave in the West Indies was no better than might be expected. In general, the owners of the plantations resided in Europe, leaving their properties to be handled by agents and overseers. This absentee landlordism left the slaves in the hands of men who were interested solely in profits, and to whom the slave was of little concern other than as a unit of labor.

Slave mortality was high. It was considered cheaper to buy than to breed: the planters held that it was less expensive to get every ounce of work out of a slave and then replace him than to try to keep him in good health. One harsh master figured that he had got his money out of a slave if he lasted for four years; less severe masters might put the figure at from five to seven years. The slave population did not reproduce itself, babies not being valued highly since the cost of rearing them was reckoned as greater than that of importing a fresh supply from Africa.

The slave codes were severe; on one of the islands the list of capital offenses included "the compassing or imagining the death of any white person." The unfree black had few personal rights, because he was defined by law as part of the personal estate of the master. A Jamaican slave had a community of masters, wrote James Stephen, nine years before he drafted the British Emancipation Act of 1833, being "a slave to every white person." True, he worked for only one white, but he stood in a servile relation to all of them, being as "totally disabled from asserting any civil, or exercising any natural rights against them," as he was against his lawful owner.

The black codes reached their peak of severity in cases of slave uprisings -- that haunting fear of the greatly outnumbered whites. Of five slaves found guilty of conspiracy in Antigua in 1728, "three of them were burnt alive, and one hang'd drawn and quarter'd, and the other transported to the Spanish coast," as reported by the island's governor, Lord Londonderry. Other means of keeping the Negroes from rebelling were the strengthening of the militia, the requirement that planters retain a specified percentage of white employees, and the deliberate mixing of Negroes of different tribal backgrounds. Since slavery was a means of control, there was a marked reluctance to grant a bondman his freedom. This was particularly true in the British possessions, Barbados levying a heavy fine on a master who liberated his slave.

Despite all precautions, Negro uprisings became a commonplace in the West Indies. Slaves felt driven to revolt by the harsh treatment, and they were emboldened to take the step because of their large numbers. As early as 1522 a slave uprising in Hispaniola set the pattern for later outbreaks in other islands, including Cuba, Puerto Rico, Martinique, Antigua, Barbados, Jamaica, St. Vincent, and the Virgin Islands. The French West Indies witnessed the greatest of these outbreaks when, in the 1790s, Toussaint L'Ouverture led the slaves in Saint Dominique -- later Haiti -- to their freedom.

The rebellious mood of the island slaves was nurtured in part by the existence of independent colonies of runaways, the first of which dated back to 1542. These Maroons, as they were called, had established themselves in the mountains and forests, staging periodic raids for food and cattle. Often they were so strong and well organized that the colonial authorities thought it best to make treaties with them. In 1739 the governor of Jamaica signed an agreement with Captain Cudjoe guaranteeing freedom to the Maroons of Trelawney Town in return for their promise to conduct themselves peacefully. This agreement was soon extended to three other Maroon groups on the island.

With the coming of the nineteenth century, West Indian slavery ceased to bring big profits; indeed, by 1807 the typical British West Indian planter was operating at a loss. Sugar from the islands was faced with a fierce competition from sugar from other areas throughout the world, particularly from the East Indies. With the market glutted, the price of West Indian sugar fell lower and lower, and the need for slaves decreased in proportion.

But this was not the swan song for slavery in the Western Hemisphere, for the lessening need for black labor in the islands was counterbalanced by the rising demand on the mainland. As slave-produced sugar declined in the West Indies, other slave-produced staples came to the fore in continental America. The commercial revolution that ushered in modern economic development at the time of Columbus was giving ground to the oncoming industrial revolution. Slave labor was at the base of both revolutions. But there was a change of locale; the seat of slavery shifted from the islands to the mainland, and the former began to export to the latter.

Many of these island-seasoned Negroes were brought into the English colonies that bordered the Atlantic. Even in their flush times, the West Indies had always shipped some of their blacks to these mainland settlements of the British Crown, where the roots of the transplanted Africans ran as deep, if not as profusely, as in the Caribbean.

To what extent did the Negro who came to the English-speaking mainland colonies bring with him the customs and beliefs of his ancestral homelands? To what extent did he retain any cultural elements from across the Atlantic? To what extent had his rich African heritage survived the harrowing overseas voyage and the seasoning years in the West Indies? This problem of African retentions is admittedly difficult. In his authoritative work The Myth of the Negro Past, Melville J. Herskovits lists several factors that determined the persistence of Africanisms, one of these being the numerical ratio of blacks to whites.

But in studying the role of the Negro in the United States, it is perhaps less important to indicate what the transplanted African retained than to describe what cultural elements he lost -- lost only because they had become an integral part of the total culture. For the Negro was destined to place his stamp upon the distinctive American contribution to the fields of music, the dance, literature, and art. Negro creations were destined to become national rather than racial, centering in the common core. A few illustrations of such fusions may be noted.

In the realm of song the idioms which the Negro brought from Africa were to be notably reflected in American music. Between native African music and that of the transplanted Negro there was a close rhythmic relationship and melodic similarity. H. E. Krehbiel, the nineteenth-century pioneer authority on the Afro-American folksongs, after analyzing 527 Negro spirituals, found their identical prototypes in African music, concluding that the essential "intervallic, rhythmical and structural elements" of these songs came from the ancestral homelands. Closely akin to the spirituals were the Negro burial hymns, "I Know Moonrise," and "Lay Dis Body Down," compilation songs that accompanied the common African custom of sitting up at night and singing over the dead. The product of two continents, these religious songs of the slave stand today as part of the spiritual heritage of America, and their appeal is universal.

The spirituals did not exhaust the vein of musical lore from Africa. Like his forebears, the American Negro found pleasure in singing while at work. Negroes who followed the sea improvised boat songs and rowing songs which had much the same rhythms as the spirituals. The rollicking steamboat songs and chanteys sung on the old clipper ships were the products of black-skinned roustabouts and deck hands. American Negroes, writes Joanna C. Colcord in Songs of American Sailormen, were "the best singers that ever lifted a shanty aboard ship." Their rhythmic tunes served as "labor-saving" devices as they stowed cotton, hoisted sail, or cast anchor, becoming part of the sailorman's repertoire ("I'm bound to Alabama,/Oh roll the cotton down").

Negro toilers on land likewise sang to ease their tasks. In such work as cleaning rice, gathering corn, or mowing at harvest, the field hands responded to the rhythms of vocal music. These plantation songs were destined to survive in the chain-gang, railroad, and hammer songs evoked in breaking stones and driving railroad spikes ("This old hammer killed John Henry, but this old hammer won't kill me").

Another musical link between the African background and the American experience was the dance. African ritual dance patterns, when brought to the New World, interacted with the secular dances from Europe, with notable results. In Latin America among the combinations springing from this fusion of African and European dance forms were the beguine, the rhumba, the conga, and the habanera. The first of these originated in Martinique; the last three are Afro-Spanish. The rhumba was first performed among Cuban Negroes as a rural dance depicting simple farm chores. The conga and the newer mambo originated among the Congo Negroes of Cuba. The music of the habanera, which takes its name from Cuba's leading city, has an African rhythmic foundation that soon came to dominate the dance melodies of Latin America, as it does today; from it came the tango (after an African word "tangana"). The national dance of Brazil, the samba, is derived directly from the wedding dance of Angola, the quizomba. The significant role of Africanisms in the dance of the Hispanic countries has been richly documented in the monumental studies of the contemporary Cuban scholar, Fernando Ortiz.

North of the Rio Grande the plantation dances of the Negro, such as the juba, were in the tradition of the circle-and-hand-clapping rounds of the Dark Continent, the feet of the encirclers beating a tattoo on the ground as a substitute for the ancestral drum. From these plantation dances emerged the Negro minstrel show. The contribution of the transplanted African to musical expression in America was summed up by Walter Damrosch in a speech at Hampton Institute in 1912: "Unique and inimitable, Negro music is the only music of this country, except that of the Indians, which can claim to be folk music."

Another African survival was the folk story. Wherever the Negro has gone, tales have gone too, and with only minor changes in plot. Negroes from the bulge of Africa brought with them legends, myths, proverbs, and the remembered outlines of animal stories that for centuries had been current at their native hearths. The best known of the adaptations of this folklore from the Dark Continent are the Uncle Remus tales, the African ancestor of Br'er Rabbit being Shulo the Hare. The very titles, such as Br'er Wolf and Sis' Nanny Goat, were carried across the Atlantic. African speech survivals are not uncommon in the United States. Lorenzo Dow Turner, after examining the vocabulary of the Gullah Negroes of coastal South Carolina and Georgia, found 4,000 West African words, "besides many survivals in syntax, inflections, sounds, and intonations."

Art too was imported. To the slave the formal fine arts -- painting and sculpture -- were closed, but his latent abilities were not to be suppressed. In Africa the handicrafts of the native tribes -- weaving, pottery, carving in wood, ivory, and bone -- were fashioned with surpassing technical finish. African Negroes had been among the first peoples to work in iron and gold, metal forging being one of their oldest arts. Bondage in the New World did not erase these ancestral skills in the handicrafts. Black artisans constructed many of the southern mansions in Charleston, Mobile, and New Orleans, embellishing them with decorative hand-wrought grills and balconies. Perhaps the best known of these antebellum colored craftsmen was Thomas Day of Milton, North Carolina, whose celebrated hand-tooled mahogany tables and divans still bring high prices on the antique market. Thus the craft work of colonial America reflected the art of Negro Africa, an art that today has won a distinctive place in modern esthetics.

The Negroes who were transported to the mainland English settlements were not brought in for their potential contribution to American music and art. The colonists had a different role in mind for them.

Copyright © 1964, 1969 by Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.

Copyright © 1987 by Benjamin Quarles

Introduction copyright © 1996 by V. P. Franklin

From Africa to the New World (to 1619)

"E pluribus unum," the national motto of the United States, means "one from many." Suggested by patriots at the outbreak of the American Revolution, this motto was originally used in a political sense, to demonstrate that out of thirteen separate states one new sovereign power had come into existence. But since the time of the Revolutionary War, this Latin expression has taken on a larger meaning. It has come to suggest that America is made up of many peoples from many lands, having become, in essence, a nation of nations. One of these many groups came from the continent of Africa, a group that was numbered among the very first to arrive in the New World.

Of the varied Old World stocks that entered America, none came from as wide a geographic area as the blacks. The vast majority came from the West Coast of Africa, a 3,000-mile stretch extending from the Senegal River, downward around the huge coastal bulge, to the southern limit of present-day Portuguese Angola. A small percentage came from Mozambique and the island of Madagascar in far-away East Africa, and still fewer came from the Sudanese grasslands that bordered the Sahara.

Just as the ancestor of the American Negro came from no single region, so he was of no single tribe or physical type. The "West Coast Negro," the predominant type that came to the New World, was marked by such characteristics as tall stature, woolly hair, broad features, full lips, little growth of hair on face or body, and a skin color approaching true black. But there was no such thing as one African "race." Slave ships bound for America carried a variety of genetic stocks, from the tallish, dark-skinned Ashanti of the forest lands north of the Gold Coast to the lighter and shorter Bantu from the Congo basin. Indeed, the difficulty of generalizing about the physical characteristics of the Negroid peoples is illustrated by the Nilotics and the Pygmies, one being the tallest group in the world (averaging nearly six feet in height) and the other being the shortest (averaging less than five feet).

These varied groups had no common tongue, no "lingua Africana." Indeed, there are more than 200 distinct languages in present-day Nigeria alone. There was no such thing as "the African personality," since the varied groups differed as much in their ways of life as in the physical characteristics they exhibited and the languages they spoke.

In their political institutions, there was much diversity. "One meets in Negro Africa," wrote Maurice Delafosse, "a whole series of States, ranging from the simple isolated family to confederations of kingdoms constituting empires." In pre-European Africa innumerable village kinship groups, no larger than a clan, were completely independent in their exercise of a kind of "grass-roots" democracy. These small political systems stood in contrast to an extensive empire-state like Songhay: at the height of its power, this empire extended from Lake Chad westward to the Atlantic, covering an area as large as Europe. Its most notable ruler was Askia Mohammed I (on the throne from 1493 to 1528), whose word carried as much authority in the hinterlands as at his own palace at Gao on the central Niger.

Although there were various types of states, the fundamental unit politically, as in other ways, was the family. This was not one man's family; rather, it was a kinship group numbering in the hundreds, but called a family because it was made up of the living descendants of a common ancestor. The dominant figure in this extended family community was the patriarch, who exercised a variety of functions, acting as peacemaker, judge, administrator, and keeper of the purse. The patriarch generally sought the advice of the recognized elders.

In the immediate family the practice of plural marriage was not uncommon; one man might have more than one wife if he could afford it. As a rule, marriages were formally arranged between the families, with some form of payment -- livestock generally -- going to the bride's parents. This "brideprice" was not meant to indicate that the wife had been bought; rather, it was a means of recompensing the bride's parents for their loss.

In their ways of making a living, as in other aspects of their culture, there were regional variations among the Africans. Dwellers along the shores of the great rivers turned to fishing and boat-making. In the grasslands the economy was primarily pastoral, the chief livestock being goats, sheep, and cattle. Some occupations were widespread, among them the hunting of game and the gathering of beans, nuts, and fruits. Each village had its corps of artisans, often organized into craft guilds. This skilled-labor class embraced pottery makers, weavers, wood carvers, and iron workers.

Most of the people worked in the fields that surrounded their villages, the basic economy being agricultural. Crops were grown on plots of land cleared by fire or by the felling of trees. Securing adequate foodstuffs from the earth was not always easy, but the tillers of the soil had learned such secrets as transplanting. Most of the produce was intended for local consumption, but some of it might be destined for sale outside the village. So important was agriculture as a means of livelihood that private possession of a tract of earth was not permitted. The land was the possession of the collective group; the individual had only the right to its use, owning nothing but the crops he raised.

Like so much else in African life, the land system was tied in with the gods. Among the peoples of the West Coast, religious forces found full and varied outlets. There was a supreme deity and a host of lesser ones, the latter being identified with such natural objects as rivers and the wind. Each god had priests and "diviners" who interpreted his will. The gods did not exhaust the heavenly host; sharing their powers were innumerable spirits, some of them ancestral, but most of them inhabiting the everyday objects of the hut and field.

Filling a definite place in the religious life of the Africans were their art forms, particularly the statuettes and masks of bronze, wood, or ivory that were produced as adjuncts to the performance of religious and magical rites. This wedding of art to experience gave to African sculpture its enduring vitality; the modern critic Alain Locke viewed these carved works as technically so mature and sophisticated that they could be rated as "classic in the best sense of the word." Since art was functional, the urge to express it was deeply ingrained.

Music, too, found universal expression. Among its manifestations were complex compositions for voice, an ear for the subtlest rhythm, and the use of a wide variety of instruments, including the drum, harp, xylophone, violin, guitar, zither, and flute. Like music, the dance was legion, being performed for any number of observances and purposes. Any event worthy of notice was celebrated by rhythmic movement -- births, marriages, or death. Each dance served its own specific purpose; the fertility dance, for example, was, in essence, a prayer that the seed might take good root in the soil and grow well.

The literature produced by the Africans was primarily oral rather than written and can be classified as professional and popular. In the former, knowledge about the history, customs, and traditions of the group was transmitted by men who made a profession of memorizing. The popular literature included tales, proverbs, and riddles passed down from one generation to another, occasionally by trained narrators, but most commonly by amateur storytellers.

In summary, the Negroes who came to the New World varied widely in physical type and ways of life, but there were many common patterns of culture. Whatever the type of state, the varied groups all operated under orderly governments, with established legal codes, and under well-organized social systems. The individual might find it necessary to submerge his will into the collective will, but he shared a deep sense of group identity, a feeling of belonging. And there was ample scope for personal expression -- in crafts, in art, in worship, or in music and the dance.

African societies before the penetration of the Europeans were not backward and static, with their people living in barbarism and savagery. A more accurate view is now being unfolded by modern-day scholars in history, anthropology, archeology, and linguistics. The fruits of their researches show that the peoples of Africa from whom the American Negro is descended have made a rich contribution to the total resources of human culture.

The modern traffic in African slaves began in the mid-fifteenth century, with Portugal taking the lead. In 1441 Prince Henry the Navigator sent one of his mariners, the youthful Antonio Gonsalves, to the West Coast to obtain a cargo of skins and oils. Landing near Cape Bojador, the young captain decided that he might please his sovereign by bringing him gifts. Taking possession of some gold dust and loading ten Africans on his cockleshell, Gonsalves made his way back to Lisbon. Henry was greatly pleased by the gold and the slaves, deeming the latter of sufficient importance to send to the Pope.

In turn, the Pope conferred upon Henry the title to all lands to be discovered to the east of Cape Blanco, a point on the West Coast some 300 miles above the Senegal. Thus began a new era. With renewed vigor Portuguese seamen pressed on with their systematic exploration of the African coastline.

These pioneers found Africa to be a treasure house. It had gold, which, in addition to being valuable in itself, was indispensable as means of paying for the products they wanted from the Orient, India especially. From the West Coast, too, came pepper and elephant tusks, ivory always having a ready market in the commercial centers of the world. But the chief prize of all was the supply of slaves, which, unlike other merchandise, seemed to be inexhaustible. Within two decades after Gonsalves's voyage off Cape Bojador, the slave trade proved to be highly profitable in the European market, and within another half-century this new labor supply was finding its greatest demand in the newly discovered lands across the Atlantic. The settlements founded in America by Spain soon opened the floodgates for all the black cargoes European bottoms could carry.

With so lucrative an African trade, it was only natural that Portugal should try to shut other nations from the profits. For nearly a century she was successful; Spain, her only likely competitor during that period, was not a maritime power, preferring to stock her colonies by means of contracts (assientos) granted by the king to merchants of other countries.

But to keep other rivals away indefinitely was far beyond Portugal's power. By the latter part of the sixteenth century her monopoly was being successfully challenged by England and France, the latter almost displacing her in the Senegal and Gambia river regions during the 1570s. During the following century the African trade attracted the Dutch, Danes, Swedes, and Brandenburg Germans. By far the most formidable of these was the Dutch, who formed a West India Company in 1621 and sixteen years later seized Elmina on the Gold Coast, Portugal's strongest fortification in Africa. For the next fifty years the Hollanders were second to none in the slave-carrying trade, a position they slowly relinquished to England after 1700.

Whatever the nation, the actual operation of the slave trade was much the same. Usually the sovereign in Europe would grant a trade monopoly to a group of favored merchants, it being assumed that the privilege of foreign commerce resided in the Crown. The merchant company was thus protected against competition, at least from interlopers of their own nationality, and could proceed to stock its ships with the goods necessary for the exchange. Such goods consisted of textiles -- woolens, linens, cottons, and silks -- knives and cutlasses; firearms, powder, and shot; and iron, copper, brass, and lead in bar form for local smithies. A staple of the trade was intoxicating drink -- rum, brandy, gin, or wine. Ships also made it a point to carry a supply of trinkets -- baubles, bells, looking-glasses, bracelets, and glass beads -- which were of negligible cost and had a fascination for native chiefs.

Upon landing for the first time, the trading company made arrangements to establish a joint fort and trading station. One of the first buildings to go up would be a barracoon, a warehouse where slaves could be kept until the voyage across the Atlantic. Thus laden with goods, and with storage space to accommodate the expected human cargo, the trader was ready to do business with the native chief. The whites did not go into the interior to procure slaves; this they left to the Africans themselves. Spurred on by the desire for European goods, one tribe raided another, seized whatever captives it could, and marched them in coffles, with leather thongs around their necks, to the coastal trading centers.

Doubtless the full enormity of what they were doing did not dawn on the African chiefs. Neither intertribal warfare nor human bondage was uncommon. Indeed, from time immemorial men in Africa had become slaves by being captured in warfare, or as a punishment for crime, or because of failure to pay debts. There was, however, no stigma of inherent inferiority attached to slave status; no hard and fast color or caste hurdles prevented a former slave from becoming free and rising to a great place. Moreover, the demand for slaves had been limited. But when the European arrived, there was a great upsurge in the market for slaves, and the native chiefs were unwilling to resist the temptations of the trade. Later, when the entire West Coast had been turned into a huge slave corral, the chiefs were unable to arrest the traffic.

With a human cargo to dispose of, the native chief was ready to negotiate with the trader. Generally the latter began by offering presents to the king -- hats and bunches of beads. Then the bargaining got under way, with the Africans usually showing great shrewdness. Merchant-owner John Barbot, trading at New Calabar in 1699, gave vent to his vexation over the haggling propensities of the king's assistant Pepprell, characterizing him as being "a sharp blade, and a mighty talking black, perpetually making sly objections against something or other, and teasing us for this or that dassy, or present, as well as for drams."

Sometimes the trader might have to do business at a loss, and sometimes he had to leave empty-handed when his goods were not wanted, even though on a previous trip the identical kind of article had gone well with the same chief. But as a rule, the trader was likely to find his goods marketable. Prices varied greatly, but the average cost of a healthy male was $60 in merchandise; a woman could be bought for $15 less. Before completing the transaction, the buyer invariably took the precaution of having the slaves examined by his physician.

When enough Negroes had been procured to make a full cargo, the next step was to get them to the West Indies with the greatest possible speed. Food was stocked for crew and slaves -- yams, coarse bananas, potatoes, kidney beans, and coconuts. Then, after having been branded for identification, the blacks came aboard, climbing up the swaying rope ladders, prodded on by whips. The sexes were placed in different compartments, with the men in leg irons. The ship then hoisted anchor and started toward the West Indies, a voyage fifty days in length if all went well. This was the "Middle Passage," so called because it was the second leg in the ship's triangular journey -- home base to Africa, thence to the West Indies, and finally back to the point of original departure.

The Middle Passage has come to have a bad name, and in truth the voyage was one of incredible rigor. When in 1679 the frigate Sun of Africa made a trip from the Gold Coast to Martinique, there were only seven deaths out of a cargo of 250 slaves, but such a light loss was exceptional. On an average, the Atlantic voyage brought death to one out of every eight black passengers. A slaver was invariably trailed by a school of man-eating sharks.

A few captains were "loose packers," but the great majority were "tight packers," believing that the greater loss in life would be more than offset by the larger cargo. On their ships the space allowed a slave was confined to the amount of deck in which he could lie down, and the decks were so narrow as to permit just enough height for the slave to crawl out to the upper deck at feeding time.

Disease took its toll, especially when the ship was struck with an epidemic of scurvy or the flux. "The Negroes are so incident to the small-pox," wrote Captain Thomas Phillips of the Hannibal, "that few ships that carry them escape without it." Adding greatly to the threat of a disease outbreak was the danger that the food and water would run short.

The hazards of nature were not as vexing as the behavior of the slaves. Some committed suicide by managing to jump through the netting that had been rigged around the ship to prevent that very step. Others seemed to have lost the will to live. To guard against such suicidal melancholy, a ceremony known as "dancing the slaves" was practiced: they were forced to jump up and down to the tune of the fiddle, harp, or bagpipes. A slave who tried to go on a hunger strike was forcibly fed, by means of a "mouth-opener" containing live coals.

The most serious danger by far was that of slave mutiny, and elaborate precautions were taken to prevent uprisings. Daily searches of the slave quarters were made, and sentinels were posted at the gun room day and night. But the captain and his undermanned crew were not always able to control their cargo of blacks. So numerous were slave insurrections on the high seas that few shipowners failed to take out "revolt insurance."

But, despite all risks and dangers, the slave trade flourished. The profits were great. After taking out all expenses, including insurance payments and sales commissions, a slaving voyage was expected to make a profit of thirty cents on the dollar. Such a lucrative trade was an outgrowth of the insatiable demand for "black ivory" in the New World.

The transplanted Africans found a variety of tasks awaiting them in the lands across the Atlantic. Their service dates almost from the discovery of America, cabin boy Diego el Negro coming with Columbus on his fourth voyage in 1502. Almost without exception, every subsequent discoverer and explorer sailing for the New World from the ports of Andalusia numbered Negroes among his crew, slaves having become common in Portugal and southern Spain. When Balboa first "stared at the Pacific," he carried thirty Negroes in his train. Hernando Cortez, conqueror of Mexico, made use of slaves in hauling the artillery that terrified the Aztecs. One of the Negroes with the Cortez expedition was the sower and reaper of the first wheat crop in America. Lucas Vasquez de Ayllon, exploring the Atlantic coast regions in 1526, was one of the earliest "conquistadores" to bring Negroes into the present boundaries of the United States. Panfilo de Navaez, who hoped to rival the exploits of Cortez, and his successor, Cabeza de Vaca, depended upon slave labor in their wanderings in the waters of the Gulf of Mexico.

The most renowned of the Negroes who accompanied the Spanish pioneers was the Moroccan, Estavanico -- scout, guide, and ambassador for Navaez and Cabeza de Vaca. In March 1539, with Estavanico as guide, a party of three Spaniards and a group of Pima Indians set out in search of the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola. Estavanico never found these nonexistent places, but his travels led him to the region of the present state of New Mexico, which he was the first man to behold, except for the aborigines. Negroes could also be found with the French explorers -- in the Great Lakes area, along the Mississippi Valley, and in Louisiana.

A slave used as a guide, like Estavanico, was out of the ordinary. It was as a laborer, rather than anything else, that the Negro was needed in the New World. For the Spanish had decided quite early that Negro labor was more suitable than Indian labor. Catholic bishops like Bartholome de Las Casas and Diego de Landa developed a marked sympathy for the Indians, and hence became strong exponents of Negro slavery. In support of this stand, a theory took root that the Indian was physically far inferior to the Negro, and thus less able to stand hard labor in a hot climate.

Aside from the attitude of the bishops, there seemed to be sound ground for the preference of the Negro over the Indian. The former showed a greater resistance to the white man's diseases -- measles, yellow fever, and malaria. Moreover, the transplanted African was better able to adjust to the discipline of the plantation system, for he came from an economic order more complex than that of the Indian.

Although slaves were used in mining gold on the mainland, particularly in New Granada, it was to the West Indies that slavery and the slave trade owed their initial enormous growth. Indeed, at the close of the eighteenth century over half of the 800,000 Negroes in Spanish America were to be found in Cuba and Puerto Rico. The islands produced a variety of commodities -- indigo, coffee, cotton, tobacco, hides, and ginger -- but their mainstay was sugar. More than all other products combined, it was sugar that created the great demand for slaves in America, and it was the sugar industry that determined their geographical distribution therein. Hitherto rare in Europe, sugar now became big business, and the West Indies were commonly called the "Sugar Islands."

Sugar cane culture readily lent itself to slave labor. Its operations were not hard to learn -- clearing land, hoeing, planting, weeding, and cane cutting -- and they provided year-round employment. Moreover, slaves could be worked in large gangs, which were easily supervised.

Just as Portugal had been unable to prevent other European powers from coming to Africa, so Spain was unable to keep her rivals out of the Caribbean. By the middle of the seventeenth century the Spanish monopoly had been broken, and Denmark, Holland, and France were establishing themselves in the islands. Spain's weakening grasp became starkly apparent when England in 1655 wrested Jamaica from her. This possession soon became the chief slave market in the Western Hemisphere.

The European powers who now planted their flags in the islands found it expedient to permit independent merchants of their nationality to share in the slave traffic, which had grown too large to be handled by one company of licensees. The mother countries were quick to sense that West Indian possessions, in addition to supplying sugar, enabled them to build up their merchant shipping by furnishing a nursery for their seamen. Island possessions also created a market for their manufactures: "The Negro-Trade and the natural consequences resulting from it," wrote a contemporary Englishman, "may be justly esteemed an inexhaustible Fund of Wealth and Naval Power to this Nation."

Although many profited from the trade, the West India planter was its backbone; it was he who kept the wheels in motion by his constant seeking of more slaves. In making his purchases, the planter, or his agent, sometimes went to the mainland marts -- Cartagena, Panama, or Vera Cruz. But, as a rule, slaves could be obtained from stocks kept in West India port barracoons. Sometimes a slave-laden ship would sail into an island port and sell its cargo to a single buyer, or to multiple buyers. Less often a slaver would sail into a planter's own waters, seeking to dispose of its blacks.

Slave purchases were made at the buyer's risk. This the planter knew. And he sensed, if he did not know, that all ship captains had orders much like that issued to Anthony Overstall, commander of the Judith: "You must be mindful to have your Negroes Shaved and made Clean to look well and strike a good impression on the Buyers at whatever place you touch at."

Once the slave was purchased, it became necessary to break him in -- to accustom him to the routines of plantation slavery in a new and strange environment. In this seasoning process -- generally running to three years -- the freshly arrived blacks would be distributed among veterans, or they would be placed under special supervisors. When the slave was fully seasoned -- having learned his work assignment, become accustomed to the food and climate, learned to understand a new language, and shaken off any tendency to suicide -- he was worth twice as much as when he first landed.

The lot of the slave in the West Indies was no better than might be expected. In general, the owners of the plantations resided in Europe, leaving their properties to be handled by agents and overseers. This absentee landlordism left the slaves in the hands of men who were interested solely in profits, and to whom the slave was of little concern other than as a unit of labor.

Slave mortality was high. It was considered cheaper to buy than to breed: the planters held that it was less expensive to get every ounce of work out of a slave and then replace him than to try to keep him in good health. One harsh master figured that he had got his money out of a slave if he lasted for four years; less severe masters might put the figure at from five to seven years. The slave population did not reproduce itself, babies not being valued highly since the cost of rearing them was reckoned as greater than that of importing a fresh supply from Africa.

The slave codes were severe; on one of the islands the list of capital offenses included "the compassing or imagining the death of any white person." The unfree black had few personal rights, because he was defined by law as part of the personal estate of the master. A Jamaican slave had a community of masters, wrote James Stephen, nine years before he drafted the British Emancipation Act of 1833, being "a slave to every white person." True, he worked for only one white, but he stood in a servile relation to all of them, being as "totally disabled from asserting any civil, or exercising any natural rights against them," as he was against his lawful owner.

The black codes reached their peak of severity in cases of slave uprisings -- that haunting fear of the greatly outnumbered whites. Of five slaves found guilty of conspiracy in Antigua in 1728, "three of them were burnt alive, and one hang'd drawn and quarter'd, and the other transported to the Spanish coast," as reported by the island's governor, Lord Londonderry. Other means of keeping the Negroes from rebelling were the strengthening of the militia, the requirement that planters retain a specified percentage of white employees, and the deliberate mixing of Negroes of different tribal backgrounds. Since slavery was a means of control, there was a marked reluctance to grant a bondman his freedom. This was particularly true in the British possessions, Barbados levying a heavy fine on a master who liberated his slave.

Despite all precautions, Negro uprisings became a commonplace in the West Indies. Slaves felt driven to revolt by the harsh treatment, and they were emboldened to take the step because of their large numbers. As early as 1522 a slave uprising in Hispaniola set the pattern for later outbreaks in other islands, including Cuba, Puerto Rico, Martinique, Antigua, Barbados, Jamaica, St. Vincent, and the Virgin Islands. The French West Indies witnessed the greatest of these outbreaks when, in the 1790s, Toussaint L'Ouverture led the slaves in Saint Dominique -- later Haiti -- to their freedom.

The rebellious mood of the island slaves was nurtured in part by the existence of independent colonies of runaways, the first of which dated back to 1542. These Maroons, as they were called, had established themselves in the mountains and forests, staging periodic raids for food and cattle. Often they were so strong and well organized that the colonial authorities thought it best to make treaties with them. In 1739 the governor of Jamaica signed an agreement with Captain Cudjoe guaranteeing freedom to the Maroons of Trelawney Town in return for their promise to conduct themselves peacefully. This agreement was soon extended to three other Maroon groups on the island.

With the coming of the nineteenth century, West Indian slavery ceased to bring big profits; indeed, by 1807 the typical British West Indian planter was operating at a loss. Sugar from the islands was faced with a fierce competition from sugar from other areas throughout the world, particularly from the East Indies. With the market glutted, the price of West Indian sugar fell lower and lower, and the need for slaves decreased in proportion.

But this was not the swan song for slavery in the Western Hemisphere, for the lessening need for black labor in the islands was counterbalanced by the rising demand on the mainland. As slave-produced sugar declined in the West Indies, other slave-produced staples came to the fore in continental America. The commercial revolution that ushered in modern economic development at the time of Columbus was giving ground to the oncoming industrial revolution. Slave labor was at the base of both revolutions. But there was a change of locale; the seat of slavery shifted from the islands to the mainland, and the former began to export to the latter.

Many of these island-seasoned Negroes were brought into the English colonies that bordered the Atlantic. Even in their flush times, the West Indies had always shipped some of their blacks to these mainland settlements of the British Crown, where the roots of the transplanted Africans ran as deep, if not as profusely, as in the Caribbean.

To what extent did the Negro who came to the English-speaking mainland colonies bring with him the customs and beliefs of his ancestral homelands? To what extent did he retain any cultural elements from across the Atlantic? To what extent had his rich African heritage survived the harrowing overseas voyage and the seasoning years in the West Indies? This problem of African retentions is admittedly difficult. In his authoritative work The Myth of the Negro Past, Melville J. Herskovits lists several factors that determined the persistence of Africanisms, one of these being the numerical ratio of blacks to whites.

But in studying the role of the Negro in the United States, it is perhaps less important to indicate what the transplanted African retained than to describe what cultural elements he lost -- lost only because they had become an integral part of the total culture. For the Negro was destined to place his stamp upon the distinctive American contribution to the fields of music, the dance, literature, and art. Negro creations were destined to become national rather than racial, centering in the common core. A few illustrations of such fusions may be noted.

In the realm of song the idioms which the Negro brought from Africa were to be notably reflected in American music. Between native African music and that of the transplanted Negro there was a close rhythmic relationship and melodic similarity. H. E. Krehbiel, the nineteenth-century pioneer authority on the Afro-American folksongs, after analyzing 527 Negro spirituals, found their identical prototypes in African music, concluding that the essential "intervallic, rhythmical and structural elements" of these songs came from the ancestral homelands. Closely akin to the spirituals were the Negro burial hymns, "I Know Moonrise," and "Lay Dis Body Down," compilation songs that accompanied the common African custom of sitting up at night and singing over the dead. The product of two continents, these religious songs of the slave stand today as part of the spiritual heritage of America, and their appeal is universal.

The spirituals did not exhaust the vein of musical lore from Africa. Like his forebears, the American Negro found pleasure in singing while at work. Negroes who followed the sea improvised boat songs and rowing songs which had much the same rhythms as the spirituals. The rollicking steamboat songs and chanteys sung on the old clipper ships were the products of black-skinned roustabouts and deck hands. American Negroes, writes Joanna C. Colcord in Songs of American Sailormen, were "the best singers that ever lifted a shanty aboard ship." Their rhythmic tunes served as "labor-saving" devices as they stowed cotton, hoisted sail, or cast anchor, becoming part of the sailorman's repertoire ("I'm bound to Alabama,/Oh roll the cotton down").

Negro toilers on land likewise sang to ease their tasks. In such work as cleaning rice, gathering corn, or mowing at harvest, the field hands responded to the rhythms of vocal music. These plantation songs were destined to survive in the chain-gang, railroad, and hammer songs evoked in breaking stones and driving railroad spikes ("This old hammer killed John Henry, but this old hammer won't kill me").

Another musical link between the African background and the American experience was the dance. African ritual dance patterns, when brought to the New World, interacted with the secular dances from Europe, with notable results. In Latin America among the combinations springing from this fusion of African and European dance forms were the beguine, the rhumba, the conga, and the habanera. The first of these originated in Martinique; the last three are Afro-Spanish. The rhumba was first performed among Cuban Negroes as a rural dance depicting simple farm chores. The conga and the newer mambo originated among the Congo Negroes of Cuba. The music of the habanera, which takes its name from Cuba's leading city, has an African rhythmic foundation that soon came to dominate the dance melodies of Latin America, as it does today; from it came the tango (after an African word "tangana"). The national dance of Brazil, the samba, is derived directly from the wedding dance of Angola, the quizomba. The significant role of Africanisms in the dance of the Hispanic countries has been richly documented in the monumental studies of the contemporary Cuban scholar, Fernando Ortiz.

North of the Rio Grande the plantation dances of the Negro, such as the juba, were in the tradition of the circle-and-hand-clapping rounds of the Dark Continent, the feet of the encirclers beating a tattoo on the ground as a substitute for the ancestral drum. From these plantation dances emerged the Negro minstrel show. The contribution of the transplanted African to musical expression in America was summed up by Walter Damrosch in a speech at Hampton Institute in 1912: "Unique and inimitable, Negro music is the only music of this country, except that of the Indians, which can claim to be folk music."

Another African survival was the folk story. Wherever the Negro has gone, tales have gone too, and with only minor changes in plot. Negroes from the bulge of Africa brought with them legends, myths, proverbs, and the remembered outlines of animal stories that for centuries had been current at their native hearths. The best known of the adaptations of this folklore from the Dark Continent are the Uncle Remus tales, the African ancestor of Br'er Rabbit being Shulo the Hare. The very titles, such as Br'er Wolf and Sis' Nanny Goat, were carried across the Atlantic. African speech survivals are not uncommon in the United States. Lorenzo Dow Turner, after examining the vocabulary of the Gullah Negroes of coastal South Carolina and Georgia, found 4,000 West African words, "besides many survivals in syntax, inflections, sounds, and intonations."

Art too was imported. To the slave the formal fine arts -- painting and sculpture -- were closed, but his latent abilities were not to be suppressed. In Africa the handicrafts of the native tribes -- weaving, pottery, carving in wood, ivory, and bone -- were fashioned with surpassing technical finish. African Negroes had been among the first peoples to work in iron and gold, metal forging being one of their oldest arts. Bondage in the New World did not erase these ancestral skills in the handicrafts. Black artisans constructed many of the southern mansions in Charleston, Mobile, and New Orleans, embellishing them with decorative hand-wrought grills and balconies. Perhaps the best known of these antebellum colored craftsmen was Thomas Day of Milton, North Carolina, whose celebrated hand-tooled mahogany tables and divans still bring high prices on the antique market. Thus the craft work of colonial America reflected the art of Negro Africa, an art that today has won a distinctive place in modern esthetics.

The Negroes who were transported to the mainland English settlements were not brought in for their potential contribution to American music and art. The colonists had a different role in mind for them.

Copyright © 1964, 1969 by Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.

Copyright © 1987 by Benjamin Quarles

Introduction copyright © 1996 by V. P. Franklin

Cuprins

Contents

Introduction by V. P. Franklin

Foreword

1 From Africa to the New World (to 1619)

2 The Colonial and Revolutionary War Negro (1619-1800)

3 The House of Bondage (1800-1860)

4 The Nonslave Negro (1800-1860)

5 New Birth of Freedom (1860-1865)

6 The Decades of Disappointment (1865-1900)

7 Turn-of-the-Century Upswing (1900-1920)

8 From "Normalcy" to New Deal (1920-1940)

9 War and Peace: Issues and Outcomes (1940-1954)

10 Democracy's Deepening Challenge (1954-1963)

11 A Fluid Front (1963-1970)

12 Widening Horizons (1970-1986)

Selected Bibliography

Index