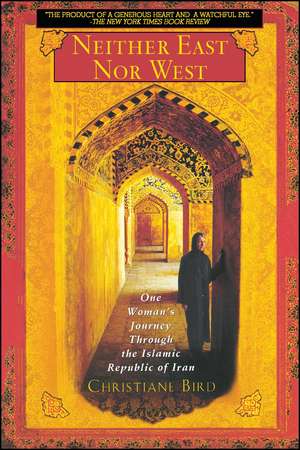

Neither East Nor West: One Woman's Journey Through the Islamic Republic of Iran

Autor Christiane Birden Limba Engleză Paperback – 15 iul 2002

Preț: 159.18 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 239

Preț estimativ în valută:

30.46€ • 33.19$ • 25.67£

30.46€ • 33.19$ • 25.67£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 02-16 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780671027568

ISBN-10: 0671027565

Pagini: 416

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Ediția:Revised

Editura: ATRIA

Colecția Atria Books

ISBN-10: 0671027565

Pagini: 416

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Ediția:Revised

Editura: ATRIA

Colecția Atria Books

Notă biografică

Christiane Bird is the author of The Jazz and Blues Lover's Guide to the U.S. and New York Handbook, and a co-author of Below the Line: Living Poor in America. A graduate of Yale University and a former travel writer for the New York Daily News, she lives in New York City.

Extras

Chapter One

There is a red line in Iran that you should not cross. But no one knows where it is.

-- Popular saying in Iran

The first time I stepped out onto the streets of Tehran, I felt like a child again. Lona, Bahman's secretary, had to hold my hand, as people and traffic rushed and roared around us. Jet lag made me unsteady on my feet, and my long, heavy black raincoat seemed to be pulling me down toward a parched pavement that was simultaneously rising up to suck at my hem. The hot August sunlight burned across my shoulders.

The crush of women in black around us was overwhelming. Left and right, shrouded figures were striding purposefully by, carrying purses and briefcases and shopping bags. Because this was fashionable north Tehran, most were dressed as I was, in a manteau -- the French word for coat that is commonly used in Iran -- and a rusari, or head scarf. The manteaus all looked alike to me, but the rusaris came in a wide variety of muted colors and designs, as well as the occasional bright blue or green. Only a few women were wearing the chador, the traditional black bell-shaped garment that covers both the head and the body and is held at the chin by a hand or teeth. But whether encircled by a rusari or a chador, the women's faces shone out like jewels.

I was both one of them and a being apart. In a few days, I would get used to my manteau and rusari and barely notice them anymore; in a month, in fact, I would feel uncomfortable when in the presence of some men without my covering. In a few days, I would visit other parts of Tehran and know that this crush of people and traffic was nothing. But for the moment, I felt lost and, despite my disguise, horribly conspicuous.

Lona, her seven-year-old daughter Sepideh, and I were heading straight for the manteau shop. Though my American raincoat had met with considerable approval from Lona's discerning eye, we'd both agreed that it was far too warm for August. We walked down a smart street, lined with plate-glass shop windows displaying everything from Gucci shoes to Nike baseball caps. We passed by one sidewalk vendor selling hot tea out of a big silver pot, another grilling ears of corn over an electric heater, and a third selling shelled walnuts out of a jar filled with salt water. The shelled walnuts looked naked, like tiny brains.

The manteau shop was close and crowded, with the racks of raincoats separated by color. Green, blue, brown, gray, cream, and lots and lots of black. Some had fancy buttons, tassels, and ties, and most had shoulder pads. An embroidered gold panel turned one garment into a semi-evening gown and a nubby hood gave another a schoolgirl look. While I looked around helplessly, not knowing where to begin, Lona tried to convince me to buy one of the black-and-brown animal prints, or at least a light-colored raincoat. To wear light colors in Iran is a mildly liberal political statement, and as a foreigner, I could get away with a lot. But I refused. For all of the colors available in the shop, I'd already noticed that most of the women in the street were wearing black. I didn't want to stand out any more than I already did. And besides, I came from New York.

Finally, I chose the thinnest black manteau I could find, and we returned to the street, where I looked around me with a heightened awareness. I could now see differences in the women's attire that I hadn't noticed before. True, most of the manteaus were black, but they were of different lengths, styles, shapes, and fabrics. Some clung, some hung, some billowed, some flattered. Some seemed matronly, some youthful, some elegant, and some -- that lovely flowing garment with the V-shaped front panel -- sexy.

There were other differences in the women's attire as well. Everyone was wearing her rusari differently, with various amounts of hair sticking out the front or back. Iranian women have perfected something called the kakol, or forelock, which is a pile of teased hair -- sometimes several inches high -- that sits atop the forehead. The kakol deliberately flouts the whole purpose of the rusari, as does the long braid or swish of loose hair hanging out the back that some younger women brandish.

The women's lower extremities also sent out various messages. Some were wearing jeans, some elegant trousers, some heavy socks, and some stockings that were daringly sheer -- another liberal political statement. Iran's Islamic dress code decrees that women keep their lower legs and feet well covered, so thin stockings, along with open-toed sandals worn without socks, are forbidden.

Equally diverse were the women's shoes. They ranged from practical flats to stylish designer heels, from sneakers to hiking boots. Variations in these last two were especially popular among the college-age women, and I instinctively knew that each one was sending out a very different signal, which I was too old and foreign to read.

I adjusted the shoulder pads of my new manteau. Now that I was wearing a lightweight Iranian garment instead of a heavy Western one, I felt a bit better. I'd also noticed one or two women with light brown, almost blond, hair and realized that Lona was nearly as tall as I was. Perhaps, as a tall, blond American woman, I didn't stand out as much as I'd thought.

A moment later, Lona nudged me and tilted her head toward a parked car against which two men in dark green uniforms without insignia of any kind were leaning. "Pasdaran," she whispered, and I tried not to stare while simultaneously realizing that the men had already noticed me notice them and had registered my Western face. So much for my fleeting hopes of not standing out.

I'd read a lot about the Pasdaran, or Revolutionary Guards, an organization formed after the revolution when the clerics did not trust the regular Iranian army, which had previously supported the Shah. Initially a small unit designed only to protect the new leaders, the Pasdaran had quickly developed into both a powerful internal security force that patrolled the streets for breaches in Islamic conduct and a full-fledged armed troops that fought in the Iran-Iraq War. The Pasdaran's civilian counterpart had been the komitehs ("committees"), volunteer organizations formed around mosques and student and workers' groups as a rival authority to the regular police. In the early 1980s, the komitehs had roamed the streets, vigilante style, arbitrarily arresting thousands of people for everything from suspected prostitution to antigovernment activities and invading private homes on a whim in search of such incriminating "un-Islamic" evidence as liquor, Western music, and chessboards. The latter were outlawed in the early years of the revolution because of their associations with gambling and royalty.

In the mid-1990s, the Pasdaran and komitehs were merged into a single "disciplinary force," but many people still refer to the uniformed guards as the "Pasdaran" or "komiteh" and can tell the difference between them. Some also call them the "morals police." Their street surveillance is far more lax than it once was, but there is still no telling when they might suddenly arrest someone. On another walk just a few days later, Lona, Sepideh, and I would pass by two guards herding three young women with tattoos and heavy makeup into a van. Both tattoos and heavy makeup are officially forbidden in the Islamic Republic, even though cosmetic stores thrive and many women wear far more makeup than do most women in the United States.

From the Pasdaran, Lona, Sepideh, and I passed on to a small, covered bazaar selling inexpensive clothes, shoes, jewelry, and spices. Plastic shopping bags emblazoned with English words hung next to the stalls: Marlboro, Winston, National. We passed by a sleepy boy sitting beside a parakeet perched on a box filled with paper packets the size of tea bags. Each packet contained a verse from Hafez, the beloved Iranian poet of the fourteenth century, and for a nominal fee, the boy instructed the parakeet to choose one for me. The Iranians consult Hafez as the Chinese consult the I Ching, and each verse serves as an obfuscated fortune that's open to various interpretations. Ambiguity is highly valued in Iran -- a fact that delighted the writer part of me.

Later, Bahman loosely translated my fortune for me:

Let us sprinkle flowers around and put wine in the cup.

Let us split the sphere open and start a new design.

If grief arises and sends an army to attack people in love,

We will join with the cup bearer and together we will uproot them.

I didn't know exactly what that verse meant, but overall, I thought, it seemed to bode quite well for the journey ahead of me.

Next to the bazaar stood the Saleh Shrine, its blue mosaic dome sweetly curved and crisscrossed with white. The dome was topped with the cupped logo of the Islamic Republic of Iran, which is a sword bracketed with four crescent moons that stands for the unity and oneness of God. "Unto Allah belong the East and the West, and whithersoever ye turn, there is Allah's countenance. Lo! Allah is All-Embracing, All-Knowing" reads the Qor'an (2:115).

Despite the many modern shops just down the street, the courtyard in front of the Saleh Shrine was teeming, mostly with older women in black chadors -- bending, pushing, swaying, tittering. The women looked much smaller to me now than they had in childhood, of course, but en masse and with their backs to me, they still elicited the same emotions -- curiosity and dread. Later, as I learned more about Iran, I would know better, but those emotions never completely disappeared.

Some of the women were sitting cross-legged on the ground and praying out loud to themselves, some were performing ablutions in a central fountain, and some were taking off their shoes to enter the shrine itself. Men in trim blue uniforms were moving through the crowd, carrying tall, electric-purple feather dusters. I stared at the flamboyant plumes in disbelief -- this was the brightest color I'd yet seen in Iran, and I couldn't imagine what they were for. At first I thought the obvious -- at about four feet long, the dusters could clean many out-of-the-way spots. But then I noticed that the men were using them to tap certain worshippers disapprovingly on the head, for improper attire or pushy behavior.

Because Lona and I were not wearing chadors, we could not enter the shrine. We could, however, enter the courtyard, and after a guard instructed me to pull down my rusari, we moved into the hooded crowd. The shrine sparkled in front of us, its eivan, or vaulted interior hall, open to the courtyard and shiny with green mosaic glass and crystal chandeliers. A wrinkled woman tried to sell me a booklet of verses from the Qor'an, but I was too busy turning this way and that, trying to take everything in at once. This was my first brush with Islam in action and I had dozens of excited questions for Lona, who spoke English about as well as I spoke Persian -- which is to say, barely. We were gesticulating wildly to each other, trying to make ourselves understood, when the dreaded duster descended. Apparently, we'd overstepped the bounds of appropriate Islamic behavior.

Moving out of the courtyard, I noticed several photocopied sheets of paper plastered onto a wall. They all depicted grim bearded men and looked like "wanted" posters. Lona told me, however, that they were death announcements.

Bahman lived in a brand new five-story apartment building in Zahfaranieh, a wealthy neighborhood in north Tehran. Less than a decade earlier, the area had been a mountain village, and when I awoke on my first mornings in Iran, I could hear the cawing of roosters from other villages located still farther north in the Alborz foothills. More than three decades earlier, when my parents were living in Iran, north Tehran as it is now known did not exist. One of its largest neighborhoods, the now-vibrant Shemiran, was then nothing more than a sparsely populated summer retreat.

Perhaps the most astonishing change that has come to Iran since the Islamic Revolution -- even more than politics and religion -- is its exponential population growth. Since 1979, the country's population has nearly doubled, from roughly 36 million to almost 65 million, and nearly two thirds of Iran's people are under the age of 25. The explosion is largely the result of government policy, which in the early years following the Revolu-tion encouraged citizens to have as many children as they could. People were needed to help spread the word of Shi'ite Islam and to replace those lost during the Iran-Iraq War. Only in the mid-1980s did the Islamic government realize the full and potentially disastrous consequences of its hasty decree -- including widespread unemployment, housing shortages, an inadequate infrastructure, and, more recently, a disaffected youth that may ultimately prove to be the government's undoing. Born after the Revolu-tion, many of these young Iranians have no memories of Khomeini -- or the Shah -- and are worried more about finding jobs than about politics. The voting age in Iran is 16 and the moderate, reform-minded President Khatami was elected largely by the young, and by women. Today, the Islamic government is aggressively pushing birth control, for which it regularly wins citations from international organizations.

I had originally planned to stay with Bahman and his wife for four or five days, or perhaps a week, tops. That, to my Western sense of hospitality and time, was already a great deal to ask of perfect strangers. My father hadn't spoken to or corresponded with Bahman for thirty years, after all. But Bahman had other ideas. I was hardly a stranger! -- I was the daughter of Frank Bird, who had taught him early lessons in medicine. And one week was nothing -- in fact, it was less than nothing. I was welcome to stay with him and his wife as long as I liked and to use their apartment as a base in which to store my things when I traveled outside of Tehran. They'd already cleared out a room for me.

Unaccustomed as I was then to the overwhelming hospitality of Persian culture, I felt a little uncomfortable. As I would learn later in my travels, however, Iranians love having houseguests and are often the most generous -- as well as sometimes the most tyrannical -- of hosts.

Because Bahman's wife, who is English, was in England when I arrived, Bahman asked his secretary Lona and her sister Pari to help him introduce me to life in Iran. Both were handsome, solidly built women in their twenties whose family had known Bahman's family for years. Both were also divorced, and Lona had her daughter Sepideh.

Lona and Pari were eager to assist me in any way they could. From a working-class family in Tabriz, they had lots of questions about America: What kind of food do we eat? Do women always wear short skirts? Is everyone tall and blond? Extremely hard workers, they didn't like to see me perform mundane personal chores, like cleaning my room or doing my own laundry, and they cooked elaborate dishes from their home province of Azerbaijan every night, even after spending long afternoons at the office: tahchin-e morgh, a baked chicken-and-rice dish with a crispy crust on top; kuku-ye sabzi, a richly textured omelet, thick with herbs; and kufteh tabrizi, Tabriz-style meatballs, made with prunes and apricots.

Lona, the older sister, had a flawless oval brown face with large almond eyes and lustrous black hair. Practical and self-confident, she seemed capable of handling virtually any situation; woe to the shopkeeper, I thought on more than one occasion, who tried to pull one over on her. She had a firm opinion on most subjects, sometimes raising her voice to shrill decibels, and an elegant taste that ran to small earrings and slim pieces of jewelry. Pari, in contrast, had a chalk-white complexion, sparkling black eyes, and striking dark eyebrows. She rarely spoke and occasionally seemed nervous. Her taste ran more to the dramatic. The sisters, however, shared a bubbling sense of humor and laughed easily, while Sepideh -- a serious child at the top of her class -- and I often looked on in mute incomprehension.

Bahman reigned over us women like a benevolent Turkic Persian prince. A short, handsome, and extremely kind man with a heavy mane of white hair, he was also originally from Tabriz, where most people are of a Turkic extraction and speak the Azeri Turkish language. Now a well-known gynecologist, he had been forced to flee Iran during the Islamic Revolution. His English wife, many Christian friends, and good income had made him an obvious probable target of the zealous revolutionaries, and he'd departed the country soon after finding the words Dr. Faratian must die written over his office door. He'd returned to Iran only in 1993, at the behest of the Iranian government, who'd extended its invitation to many other expatriated professionals as well. Bahman was one of the few who'd taken the government up on its offer. He'd had a more than comfortable life in England, he told me, but Iran was his country and he wanted to help his people.

Bahman's return to Iran gave him special status both in the community and among government officials, but he was nonetheless in an awkward position. While in England, he'd been part of the infertility team that had developed the world's first in vitro fertilizations. His return to Iran had been especially welcomed because he could bring with him the latest infertility techniques and introduce them to his colleagues. But men are no longer allowed to train as gynecologists in Iran -- Islamic law forbids it -- and so Bahman was one of a dying breed. All those who attended his lectures were women, and some of those women resented his gender. Some of his techniques, such as artificial insemination, were also highly problematic at first. In a traditional Islamic society, a woman can become legally pregnant only by her husband. Artificial insemination is therefore not allowed, and during his first years back, Bahman had had to obtain a special decree from Supreme Leader Khamene'i himself whenever he'd wanted to perform the procedure.

Bahman talked about my father as a young man in a way that made me catch my breath. He remembered how my father had paced before he was to perform an operation, reviewing human anatomy in his head, and how he'd studied his patients' hands for clues as to their illnesses. He remembered several field trips the two of them had taken together and could still imitate my father's cramped signature perfectly, down to the dashing F and illegible -ird. My father has always talked about Bahman with a great deal of fondness, but I knew that he didn't remember him in such detail. To my father, then already an accredited doctor from a powerful country, Bahman had been just a student 10 years his junior. To Bahman, the son of a bus driver from a provincial city, my father had been a learned man, representing the then seemingly omnipotent, technically advanced West. Now, though, it was Bahman who was the famous physician.

Despite the wealth of Bahman's neighborhood, it -- like much of Tehran -- had a cluttered, ragged, unfinished feel. Many of its new apartment buildings sported ersatz resortlike facades, only vaguely protected by flimsy walls that seemed to mock the old Persian ideal of hiding one's home behind thick clay bulwarks. Construction was going on in many of the streets, few of which had sidewalks, and cranes sat like dozing vultures atop at least a half-dozen buildings. Many of these cranes never moved an inch during my stay; running out of money while building is not unusual in inflation-rife Iran.

Along the short, dusty road that descended from Bahman's apartment to the main street ran a jube, or concrete water channel. During the spring, when the snow melts in the Alborz Mountains, or after a rain, the jube fills with water that then travels downstream to the city center. My parents had told me stories about the jubes and how in their time they'd been used both for washing clothes and as sewers, and so I was surprised to see them in the wealthy north. But water is a precious commodity in Iran -- the average rainfall is only 12 inches a year -- and jubes, I later found out, still line many of Tehran's main streets, where they sometimes join with surfacing underground streams. Some of these rushing waterways are three or four feet wide, and I often saw boys playing in them.

A jube had run outside our home in Tabriz, I remembered then in a flash, but our parents had never let us get near it, let alone play in it. Not surprisingly, they'd been worried about disease. But we had had two white-and-tan "jube dogs" -- as the strays were called -- as pets, much to the horror of our Iranian servants. Generally speaking, traditional Iranians do not keep dogs as pets. They regard them as unclean.

By the side of the road one block south of Bahman's apartment was a blue box cupped with painted yellow hands, with a plywood dove on top. It sat on a post about three feet tall and had a slit for money. ALMS MAKE YOU RICHER AND TO GIVE ALMS IS TO PROTECT YOURSELF AGAINST SEVENTY KINDS OF EVIL EYES read words stenciled on the sides. To give money to the poor is one of the five basic tenets of Islam, and thousands upon thousands of donation boxes fleck the Iranian landscape. Most of the boxes are a standard, machine-made blue and yellow, with a plywood dove, rose, or tulip on top, but I also noticed several homemade-looking versions. Iranians take their obligation of giving very seriously, and people often stop to push faded bills into the money slots. The proceeds go to the Helping Committee of Imam Khomeini, a charity organization that was set up following the Revolution to provide services for the poor. Charitable foundations in Iran have a widespread reputation for mind-boggling corruption -- said to run into many millions of dollars -- but they are at least somewhat effective: I saw relatively few beggars in the Islamic Republic.

Two blocks south of Bahman's apartment stood a cluster of small gaping shops selling dry goods, vegetables, and meat. The shops had rolling iron grills for doors and sold a mix of Iranian and European wares -- Lux, Mazola, Bic, Crest, Nescafé. Next door stood a bakery, dark, ancient, and hot, with a red fire roaring in a clay oven in the back and flour-dusted men tossing balls of dough up front. They were making sangak, one of four kinds of Persian flat bread, which is stretched out into the shape of an elongated pizza and baked until it is brown and bumpy on top. Most Iranians buy their bread fresh every day, and wherever I traveled in the country, I passed boys on bicycles, pedaling home with limp slabs of bread big as tabloid newspapers draped across their handlebars.

Actual newspapers and magazines were sold from a kiosk in front of the neighborhood shops. Among the dozens offered were the three English-language newspapers published in Tehran -- Iran News, Tehran Times, and Iran Daily -- and the international editions of Time and Newsweek, sold in sealed cellophane wrappers. The magazines' text was never censored, but all photos that were deemed offensive -- those depicting women with cleavage or women with exposed hair, arms, or legs -- were blacked out with a marker.

The three English-language newspapers were slim affairs, published primarily for Iran's diplomatic and Western-educated communities. Tehran Times was put out by Kayhan, a well-established, hard-line newspaper; Iran Daily was supported by the moderates; and Iran News straddled the philosophical difference between the two. Or so I was told, because in reality I could see only minor differences among the publications, all of which usually supported government policy.

For more controversial news coverage, I would have had to go to the Persian-language newspapers, which, unfortunately, I couldn't read. I was in Iran during a remarkable flowering of the press. In the year and a half following Khatami's election, the number of newspapers published in the country had more than quadrupled, until they numbered over 120. Most popular among them during my visit were Hamshahri, supported by Tehran's former mayor, the then recently ousted Gholam-Hosein Karbaschi, and Tus, supported by President Khatami. In Iran, newspapers are financed not through advertising and circulation but rather by political parties or organizations.

Every morning along major streets and highways, I saw vendors waving copies of Hamshahri and Tus, which citizens rushed to buy. Though there had been some muted freedom of the press in the Islamic Republic since the early 1990s, newspapers at the time of my visit were publishing stories that openly criticized the government and/or exposed some of Iran's many social problems. Hamshahri took a cautious approach, but Tus was frighteningly bold. They're going too far, people whispered among themselves, and they were right. Tus was closed down numerous times just before, during, and after my stay -- only to be started up again and again under different names. Repression in Iran is far from absolute, and the "new" papers were usually allowed to keep the "old" paper's address, printing presses, and staff. Finally, however, in November 1999, the newspaper's editor, Mashallah Shamsolva'ezin, was put on trial and sentenced to 30 months in prison.

North Tehran backs up into the embrace of the Alborz Mountains, the most defining physical characteristic of the city. Bone dry and nearly devoid of vegetation in many parts, the Alborz are a living, breathing, shape-shifting presence that seems to stretch, yawn, buckle, and bend as it looms over the metropolis like a giant elephant in repose. One unexpected jerk in the middle of its usually protective sleep and it could kick the entire city right out of its foothills.

Sometimes the Alborz -- as high as the American Rockies -- are all ridges, valleys, rocks, and sand, with sunlight illuminating a hidden cliff here, an unexpected rockslide there. Sometimes the Alborz are a flat, impenetrable, dun-colored wall, separating Tehran -- and by extension, it seems, all of Iran -- from the rest of the world. Sometimes the Alborz are sensual, red-hued, and comforting. Sometimes the Alborz are craggy, black, and forbidding.

Sensitive to every nuance of light and atmosphere, the Alborz subtly change color with the day. Though often a dull gray or maroon at first glance, closer looks reveal shifting green streaks, pink splotches, and purple peaks. A cloud passes over, casting down a blue patch.

On especially sunny days in north Tehran, the light of the Alborz reminded me of the light of my early childhood. This was the same stark backdrop across which my memories were moving. The air was buoyant, the slopes bleak.

On other days, though, as I wandered through the heart of the downtown, I would forget all about the mountains -- often rendered close to invisible by horrendous pollution. Along with Mexico City and Bangkok, Tehran is one of the most polluted cities in the world. But then a ray of sunlight would glance off a snowy peak or the sense of a powerful presence would make me look up. And then, there they were again, the Alborz, which have haunted Iran's consciousness since its very beginnings.

The ancient Persians believed that the Alborz grew from the surface of the earth, taking 800 years to reach their full height, as their roots reached deep into the ground and their peaks attached themselves to the sky. The stars, sun, and moon were thought to revolve around these peaks, and they became the mythological home of Mithra, the god of the cosmic order who later became known as the sun god in both Iran and India. Mithra and the creation of the Alborz are described in the Avesta, the holy book of the Zoroastrian religion. An ancient faith, founded in what is now Iran between 1000 and 700 B.C., Zoroastrianism was the first known belief system to posit the concepts of life as a perennial struggle between good and evil, individual responsibility for moral behavior, the resurrection of the body, the Last Judgment, and life everlasting. Islam, Judaism, and Christianity all trace many articles of their faiths back to Zoroastrianism.

To the east of Tehran, and visible only from certain angles of the city, is the Alborz's highest peak, Mount Damavand (18,602 feet). A magnificent cone-shaped volcano that is perpetually covered with snow, Mount Damavand is to Iran what Mount Fuji is to Japan and Kilimanjaro is to Tanzania.

Mount Damavand is home to many legendary Persian figures, including the magical bird Simorgh, whose nest is said to be close to the sun, and the evil ruler Zahhak, who is living out eternity bound in chains at the bottom of a well deep inside the mountain. Though a hero as a youth, Zahhak was seduced by the devil, who exploited his ignorance of evil and talked him into murdering his father. In return, promised the devil, Zahhak would become not only ruler of his father's lands but also ruler of all the world. As soon as the pact was made, two black snakes suddenly sprouted out of Zahhak's shoulders. He cut off their heads, but they instantly grew back again and demanded to be fed the brains of two strong men every day. Thereafter began a reign of terror that lasted for 1,000 years, until the arrival of Fereydun, a youth as tall and slim as a cypress tree, with a face as fair as the silver moon. Born in a village on Mount Damavand, Fereydun struck Zahhak with a bull-headed mace and was about to cut off his head when an angel appeared and told him to lock Zahhak inside the mountain instead, as a warning to all future men. Fereydun did so, and there Zahhak lives to this day.

A sort of modern-day equivalent of Zahhak is the notorious Evin prison, situated in the soft brown foothills of the Alborz on the northwestern edge of the city. Once part of a suburb, Evin now belongs to Tehran proper and is only a short distance away from the sleek, luxurious Azadi Grand Hotel, many of whose rooms overlook the prison. Azadi means "freedom," but when I commented on the obvious irony of its name to my new Iranian friends, they just shrugged. In Iran, people are used to living beside the absurd.

While in Tehran, I passed by Evin prison nearly every day on my way downtown from Bahman's. From the outside, it looked tame and innocuous. Serrated brown walls zigzagged their way up one hillside to disappear into a valley behind, and to reappear again on the far hillside. Inside the walls, the prison appeared to be largely empty space -- I caught only occasional glimpses of buildings resembling dormitories and sheds. But at night, everything changed. Bright, hot prison spotlights flicked on, reminding me in one suffocating instant of Evin's horrific history.

During the reign of the Shah, the prison was the stronghold of SAVAK, the ruthless secret police trained by the American CIA and the Israeli Mossad, and after the revolution, thousands of political prisoners were tortured and others put to death there. Today's version of SAVAK, SAVAMA, has nothing approaching the zealous reputation of its predecessor, thought by various human rights organizations to have held between 25,000 and 100,000 Iranians political prisoner in the mid-1970s. However, whereas SAVAK concentrated primarily on political dissidents, SAVAMA keeps tabs on the most mundane details of ordinary citizens' lives. And there are still far too many stories of men and women disappearing into Evin's bowels for inexplicable reasons and unspecified periods of time. For the year that I was in Iran, Amnesty International's annual report on the country read:

Hundreds of political prisoners, including prisoners of conscience, were held. Some were detained without charge or trial; others continued to serve long prison sentences imposed after unfair trials. Reports of torture and ill-treatment continued to be received and judicial punishments of flogging and stoning continued to be imposed....Scores of people were reportedly executed, including at least one prisoner of conscience; however, the true number may have been considerably higher.

"Da-da-da-da-da-da, da-da-da-da-da-da -- " I was on hold with the Foreign Correspondents and Media Department of the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. It took me a moment to place the jingly tune I was listening to, but when I did, I started -- and would have laughed, had I not been so nervous. Scott Joplin's "The Entertainer," here in the Islamic Republic of Iran, which throughout most of the 1980s had banned all popular Western and Persian music from its airwaves. I knew that things had eased up considerably since then, but I still hadn't expected to hear American ragtime music coming from the offices of a government organization. Somehow, it seemed even more surprising to me than the illegal Michael Jackson and Pink Floyd tapes I'd already heard blaring out of taxi cabs.

A Mr. Ali Reza Shiravi came on the line. Yes, he and his colleagues were expecting me. Please be in his office the next morning at 10:00.

I hung up, almost trembling. Someone had already called Bahman earlier that morning to confirm that I was staying with him, as I'd claimed on my entrance papers. And now I was about to meet with the government officials who would be keeping tabs on me during my stay in Iran. I had no idea whether they'd help or hinder my travels, but I expected the worst.

Established shortly after the revolution, the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance is ubiquitous in Iran. Referred to simply as Ershad, or Guidance, by most Iranians, it monitors virtually every aspect of life in Iran, with the intent -- as its name implies -- of upholding Islamic standards. Among many other things, Ershad censors the media; decides what films, plays, art exhibits, and concerts can be produced; establishes the educational curricula of schools and universities; organizes the tourism industry, including pilgrimages to Mecca; and monitors financial and judicial institutions.

I arrived at one of Ershad's many branches shortly before 10:00 the next morning. My heart was racing and my throat was dry -- Just why was it again that I'd wanted to come to Iran? I half asked myself. A grim bearded man at the entrance waved me toward an elevator, and I rode up to the sixth floor, nearly tripping over my manteau as I exited its narrow confines. Once I was inside the Foreign Correspondents Department, however, a woman in a chador welcomed me with an application form and a smile that put me somewhat more at ease.

As I sat down to fill out the form, sweat trickling down my back, she joined me, along with another woman dressed in a magnificent blue-checked robe with yellow highlights and cuffs, cinched in by a wide sash. Around her face was pinned a pure white hood that gave her a beatific look, and to the top of her head was attached the black chador, which streamed behind her like a dramatic cape. Both women wanted to know more about me and my project, and to my surprise, the one in the blue-checked robe wanted me to take back a letter to relatives living in New York.

Later in my travels, I would get used to this sort of request. Despite the image that most Westerners have of Iran as a closed-off society, many Iranians have relatives living in the West, and there is much contact between Iran and its diaspora.

Mr. Shiravi beckoned me into his office. His telephone voice had led me to expect a forbidding, humorless presence, but instead I met a friendly, bemused-looking man in his thirties, wearing a pinstriped shirt and light blue polyester pants pulled up high on his waist. We talked about Iranian poetry for a few moments and then started discussing my itinerary. Mr. Shiravi explained that I would need letters of permission from his office to interview certain people in Tehran and to visit all cities and regions outside Tehran. Tourists, who usually traveled in groups, did not need such letters, and technically speaking, I could travel without them as well. However, as a single reporter asking questions, I might be stopped by local authorities and the letters would provide me with protection. I would also have to be accompanied by a translator-guide. What was the name of my translator-guide?

I had none and nervously told him so. We returned to discussing my itinerary for a moment, but almost immediately, Mr. Shiravi raised the translator-guide question again. He seemed eager to put a name down in my file. I, however, did not want to have a constant companion by my side. I hoped to wander about on my own and hire a translator only when I needed one. But that seemed to be a foreign concept to Mr. Shiravi, used to having journalists in town on a short-term basis to cover specific stories.

I thought about Mr. Zamani back in New York and his insistence that I travel with a friend. Perhaps Mr. Shiravi's concern about my nonexistent translator-guide stemmed from the same kind of worries that Mr. Zamani had -- whatever they were. Cautiously I asked Mr. Shiravi if I would be allowed to stay in hotels by myself. Yes, he said, smiling, and then said that whereas I might be able to get away without a translator-guide in Tehran -- since I was staying with friends -- I would definitely need one when I was traveling. I would also have to provide him with information on where I would be staying when outside Tehran. He was sorry, but his Boss insisted on it.

Oh, no, I thought to myself. I had hoped to travel more spontaneously than that.

I would have to deal with that problem later, however. First, I had to find out about my bigger worry -- extending my visa from one month to three. My ideal plan was to spend three to four weeks in Tehran, and then another two months or so traveling around the country. I wanted to make one loop north to the Valley of the Assassins, the Caspian coast, Tabriz, and Sanandaj, and another loop south to Qom, Esfahan, Shiraz, Kerman, and Yazd. I also hoped to visit Mashhad and Gonbad-e Kavus.

"Oh, don't worry about your visa," Mr. Shiravi said heartily as I broached the subject, but his face fell again when I told him how much longer I wished to stay. "I don't know about two months," he mumbled. "You'll have to talk to the Boss about that."

After Mr. Shiravi and I were done, he asked the women in the front office to type up the four initial permission letters I'd requested: one that would allow me to visit Jamaran, where Ayatollah Khomeini had once lived; another for Friday prayers at the University of Tehran; a third granting me leave to interview people on the street; and a fourth giving me permission to interview mourners at the Behesht-e Zahra cemetery. As it turned out, I never had to use either of these last two letters -- or most of the other permission letters that I obtained later.

The women typed up the letters while I waited. And waited and waited. The Boss had to sign them, and no one knew where he was. Sitting on Mr. Shiravi's couch, I fretted about my visa -- how could I plan my travels if I didn't know how long I'd be in Iran? -- while Mr. Shiravi shuffled through papers. It was a scene that would be repeated many times during my stay in the Islamic Republic. The Boss was often out of the office and Mr. Shiravi was often deluged with work. I got used to watching him frown and massage his brow as he plowed through endless details of reporters' itineraries. Every move of every stay had to be carefully documented, with dates, addresses, and names, ID numbers, and telephone numbers of translator-guides.

Finally, the Boss arrived and I was hurried down the hall into a long, L-shaped room. None of the informal friendliness of the outer offices existed here. The Boss, bearded and distant, was all unsmiling business, and once again, I started to sweat. Made of a thin fabric or not, my polyester manteau was hot.

No, the Boss said in answer to my question, he doubted that I could get my visa extended for two months, because although he personally didn't care how long I stayed in Iran, the Ministry of Immigration would wonder at what an American was doing wandering around the country for three months. Yes, he snorted when I tried to argue the merits of my case, maybe Americans didn't get much news of Iran, but his office had an average of 30 American journalists coming through every month (a number I found hard to believe). Had Mr. Shiravi explained to me that I could not apply for a visa extension until a few days before the old one expired, and that I was not allowed to work with any other journalists while in the country? I should also take several basic precautions: Never show my passport or money to anyone on the street, and never get into a car, even if commanded to do so by someone in uniform. Instead, hail a taxi and follow behind.

Over the next few months, I would visit or telephone the Foreign Correspondents and Media Department many times, and in the beginning, every contact I had with them quickened my pulse. Several times, Mr. Shiravi called me unexpectedly to check up on some point, setting my heart to racing, and often I wondered to what extent my movements were being tracked. Bahman had told me that he'd sometimes suspected his phone of being tapped, and I imagined Ershad noting what kinds of appointments I set up. I worried when, during an early phone call, I inadvertently mentioned the name of a hated opposition leader, and the drinking I'd witnessed in private homes. I also knew that the Foreign Correspondents Department was checking up on my itinerary -- staff members had called the family that I was planning to visit in Qom and checked to see whether Lona and Pari were really traveling with me to Mashhad.

But as time went on, I began to realize that to a large extent, the Foreign Correspondents Department was just going through the motions. Yes, staff members had checked up on Lona and Pari, but they hadn't asked whether they were translator-guides, as I'd implied but not actually said. And yes, they'd called the various tour guides outside Tehran whose names I'd given them to ask if they'd heard of me. But I intended to hire these guides for only a half-day each and spend the rest of my time unsupervised; no one inquired about that. And after my first two trips out of Tehran, the Foreign Correspondents Department stopped asking me where I'd be staying. Was that because its staff was no longer worried that I might be a spy or because they forgot? And why did they want to monitor me anyway? Because they thought I might be up to no good or because they were worried that something might happen to me? The longer I stayed in Iran, the more convinced I became that the latter was the case. Mr. Shiravi and his colleagues seemed genuinely concerned about my welfare and went out of their way to help me as much as they could.

All of which is not to say that someone was not tracking my movements. If not the Foreign Correspondents Department, then perhaps some other branch of Ershad, or the police, or immigration, or intelligence. With the exception of one minor incident in Yazd, which I describe in more detail below, I never noticed anyone following me, but in Iran, as I was told over and over again, you just never know. Someone could always be watching, waiting for you to step over an invisible line.

Copyright © 2001 by Christiane Bird

There is a red line in Iran that you should not cross. But no one knows where it is.

-- Popular saying in Iran

The first time I stepped out onto the streets of Tehran, I felt like a child again. Lona, Bahman's secretary, had to hold my hand, as people and traffic rushed and roared around us. Jet lag made me unsteady on my feet, and my long, heavy black raincoat seemed to be pulling me down toward a parched pavement that was simultaneously rising up to suck at my hem. The hot August sunlight burned across my shoulders.

The crush of women in black around us was overwhelming. Left and right, shrouded figures were striding purposefully by, carrying purses and briefcases and shopping bags. Because this was fashionable north Tehran, most were dressed as I was, in a manteau -- the French word for coat that is commonly used in Iran -- and a rusari, or head scarf. The manteaus all looked alike to me, but the rusaris came in a wide variety of muted colors and designs, as well as the occasional bright blue or green. Only a few women were wearing the chador, the traditional black bell-shaped garment that covers both the head and the body and is held at the chin by a hand or teeth. But whether encircled by a rusari or a chador, the women's faces shone out like jewels.

I was both one of them and a being apart. In a few days, I would get used to my manteau and rusari and barely notice them anymore; in a month, in fact, I would feel uncomfortable when in the presence of some men without my covering. In a few days, I would visit other parts of Tehran and know that this crush of people and traffic was nothing. But for the moment, I felt lost and, despite my disguise, horribly conspicuous.

Lona, her seven-year-old daughter Sepideh, and I were heading straight for the manteau shop. Though my American raincoat had met with considerable approval from Lona's discerning eye, we'd both agreed that it was far too warm for August. We walked down a smart street, lined with plate-glass shop windows displaying everything from Gucci shoes to Nike baseball caps. We passed by one sidewalk vendor selling hot tea out of a big silver pot, another grilling ears of corn over an electric heater, and a third selling shelled walnuts out of a jar filled with salt water. The shelled walnuts looked naked, like tiny brains.

The manteau shop was close and crowded, with the racks of raincoats separated by color. Green, blue, brown, gray, cream, and lots and lots of black. Some had fancy buttons, tassels, and ties, and most had shoulder pads. An embroidered gold panel turned one garment into a semi-evening gown and a nubby hood gave another a schoolgirl look. While I looked around helplessly, not knowing where to begin, Lona tried to convince me to buy one of the black-and-brown animal prints, or at least a light-colored raincoat. To wear light colors in Iran is a mildly liberal political statement, and as a foreigner, I could get away with a lot. But I refused. For all of the colors available in the shop, I'd already noticed that most of the women in the street were wearing black. I didn't want to stand out any more than I already did. And besides, I came from New York.

Finally, I chose the thinnest black manteau I could find, and we returned to the street, where I looked around me with a heightened awareness. I could now see differences in the women's attire that I hadn't noticed before. True, most of the manteaus were black, but they were of different lengths, styles, shapes, and fabrics. Some clung, some hung, some billowed, some flattered. Some seemed matronly, some youthful, some elegant, and some -- that lovely flowing garment with the V-shaped front panel -- sexy.

There were other differences in the women's attire as well. Everyone was wearing her rusari differently, with various amounts of hair sticking out the front or back. Iranian women have perfected something called the kakol, or forelock, which is a pile of teased hair -- sometimes several inches high -- that sits atop the forehead. The kakol deliberately flouts the whole purpose of the rusari, as does the long braid or swish of loose hair hanging out the back that some younger women brandish.

The women's lower extremities also sent out various messages. Some were wearing jeans, some elegant trousers, some heavy socks, and some stockings that were daringly sheer -- another liberal political statement. Iran's Islamic dress code decrees that women keep their lower legs and feet well covered, so thin stockings, along with open-toed sandals worn without socks, are forbidden.

Equally diverse were the women's shoes. They ranged from practical flats to stylish designer heels, from sneakers to hiking boots. Variations in these last two were especially popular among the college-age women, and I instinctively knew that each one was sending out a very different signal, which I was too old and foreign to read.

I adjusted the shoulder pads of my new manteau. Now that I was wearing a lightweight Iranian garment instead of a heavy Western one, I felt a bit better. I'd also noticed one or two women with light brown, almost blond, hair and realized that Lona was nearly as tall as I was. Perhaps, as a tall, blond American woman, I didn't stand out as much as I'd thought.

A moment later, Lona nudged me and tilted her head toward a parked car against which two men in dark green uniforms without insignia of any kind were leaning. "Pasdaran," she whispered, and I tried not to stare while simultaneously realizing that the men had already noticed me notice them and had registered my Western face. So much for my fleeting hopes of not standing out.

I'd read a lot about the Pasdaran, or Revolutionary Guards, an organization formed after the revolution when the clerics did not trust the regular Iranian army, which had previously supported the Shah. Initially a small unit designed only to protect the new leaders, the Pasdaran had quickly developed into both a powerful internal security force that patrolled the streets for breaches in Islamic conduct and a full-fledged armed troops that fought in the Iran-Iraq War. The Pasdaran's civilian counterpart had been the komitehs ("committees"), volunteer organizations formed around mosques and student and workers' groups as a rival authority to the regular police. In the early 1980s, the komitehs had roamed the streets, vigilante style, arbitrarily arresting thousands of people for everything from suspected prostitution to antigovernment activities and invading private homes on a whim in search of such incriminating "un-Islamic" evidence as liquor, Western music, and chessboards. The latter were outlawed in the early years of the revolution because of their associations with gambling and royalty.

In the mid-1990s, the Pasdaran and komitehs were merged into a single "disciplinary force," but many people still refer to the uniformed guards as the "Pasdaran" or "komiteh" and can tell the difference between them. Some also call them the "morals police." Their street surveillance is far more lax than it once was, but there is still no telling when they might suddenly arrest someone. On another walk just a few days later, Lona, Sepideh, and I would pass by two guards herding three young women with tattoos and heavy makeup into a van. Both tattoos and heavy makeup are officially forbidden in the Islamic Republic, even though cosmetic stores thrive and many women wear far more makeup than do most women in the United States.

From the Pasdaran, Lona, Sepideh, and I passed on to a small, covered bazaar selling inexpensive clothes, shoes, jewelry, and spices. Plastic shopping bags emblazoned with English words hung next to the stalls: Marlboro, Winston, National. We passed by a sleepy boy sitting beside a parakeet perched on a box filled with paper packets the size of tea bags. Each packet contained a verse from Hafez, the beloved Iranian poet of the fourteenth century, and for a nominal fee, the boy instructed the parakeet to choose one for me. The Iranians consult Hafez as the Chinese consult the I Ching, and each verse serves as an obfuscated fortune that's open to various interpretations. Ambiguity is highly valued in Iran -- a fact that delighted the writer part of me.

Later, Bahman loosely translated my fortune for me:

Let us sprinkle flowers around and put wine in the cup.

Let us split the sphere open and start a new design.

If grief arises and sends an army to attack people in love,

We will join with the cup bearer and together we will uproot them.

I didn't know exactly what that verse meant, but overall, I thought, it seemed to bode quite well for the journey ahead of me.

Next to the bazaar stood the Saleh Shrine, its blue mosaic dome sweetly curved and crisscrossed with white. The dome was topped with the cupped logo of the Islamic Republic of Iran, which is a sword bracketed with four crescent moons that stands for the unity and oneness of God. "Unto Allah belong the East and the West, and whithersoever ye turn, there is Allah's countenance. Lo! Allah is All-Embracing, All-Knowing" reads the Qor'an (2:115).

Despite the many modern shops just down the street, the courtyard in front of the Saleh Shrine was teeming, mostly with older women in black chadors -- bending, pushing, swaying, tittering. The women looked much smaller to me now than they had in childhood, of course, but en masse and with their backs to me, they still elicited the same emotions -- curiosity and dread. Later, as I learned more about Iran, I would know better, but those emotions never completely disappeared.

Some of the women were sitting cross-legged on the ground and praying out loud to themselves, some were performing ablutions in a central fountain, and some were taking off their shoes to enter the shrine itself. Men in trim blue uniforms were moving through the crowd, carrying tall, electric-purple feather dusters. I stared at the flamboyant plumes in disbelief -- this was the brightest color I'd yet seen in Iran, and I couldn't imagine what they were for. At first I thought the obvious -- at about four feet long, the dusters could clean many out-of-the-way spots. But then I noticed that the men were using them to tap certain worshippers disapprovingly on the head, for improper attire or pushy behavior.

Because Lona and I were not wearing chadors, we could not enter the shrine. We could, however, enter the courtyard, and after a guard instructed me to pull down my rusari, we moved into the hooded crowd. The shrine sparkled in front of us, its eivan, or vaulted interior hall, open to the courtyard and shiny with green mosaic glass and crystal chandeliers. A wrinkled woman tried to sell me a booklet of verses from the Qor'an, but I was too busy turning this way and that, trying to take everything in at once. This was my first brush with Islam in action and I had dozens of excited questions for Lona, who spoke English about as well as I spoke Persian -- which is to say, barely. We were gesticulating wildly to each other, trying to make ourselves understood, when the dreaded duster descended. Apparently, we'd overstepped the bounds of appropriate Islamic behavior.

Moving out of the courtyard, I noticed several photocopied sheets of paper plastered onto a wall. They all depicted grim bearded men and looked like "wanted" posters. Lona told me, however, that they were death announcements.

Bahman lived in a brand new five-story apartment building in Zahfaranieh, a wealthy neighborhood in north Tehran. Less than a decade earlier, the area had been a mountain village, and when I awoke on my first mornings in Iran, I could hear the cawing of roosters from other villages located still farther north in the Alborz foothills. More than three decades earlier, when my parents were living in Iran, north Tehran as it is now known did not exist. One of its largest neighborhoods, the now-vibrant Shemiran, was then nothing more than a sparsely populated summer retreat.

Perhaps the most astonishing change that has come to Iran since the Islamic Revolution -- even more than politics and religion -- is its exponential population growth. Since 1979, the country's population has nearly doubled, from roughly 36 million to almost 65 million, and nearly two thirds of Iran's people are under the age of 25. The explosion is largely the result of government policy, which in the early years following the Revolu-tion encouraged citizens to have as many children as they could. People were needed to help spread the word of Shi'ite Islam and to replace those lost during the Iran-Iraq War. Only in the mid-1980s did the Islamic government realize the full and potentially disastrous consequences of its hasty decree -- including widespread unemployment, housing shortages, an inadequate infrastructure, and, more recently, a disaffected youth that may ultimately prove to be the government's undoing. Born after the Revolu-tion, many of these young Iranians have no memories of Khomeini -- or the Shah -- and are worried more about finding jobs than about politics. The voting age in Iran is 16 and the moderate, reform-minded President Khatami was elected largely by the young, and by women. Today, the Islamic government is aggressively pushing birth control, for which it regularly wins citations from international organizations.

I had originally planned to stay with Bahman and his wife for four or five days, or perhaps a week, tops. That, to my Western sense of hospitality and time, was already a great deal to ask of perfect strangers. My father hadn't spoken to or corresponded with Bahman for thirty years, after all. But Bahman had other ideas. I was hardly a stranger! -- I was the daughter of Frank Bird, who had taught him early lessons in medicine. And one week was nothing -- in fact, it was less than nothing. I was welcome to stay with him and his wife as long as I liked and to use their apartment as a base in which to store my things when I traveled outside of Tehran. They'd already cleared out a room for me.

Unaccustomed as I was then to the overwhelming hospitality of Persian culture, I felt a little uncomfortable. As I would learn later in my travels, however, Iranians love having houseguests and are often the most generous -- as well as sometimes the most tyrannical -- of hosts.

Because Bahman's wife, who is English, was in England when I arrived, Bahman asked his secretary Lona and her sister Pari to help him introduce me to life in Iran. Both were handsome, solidly built women in their twenties whose family had known Bahman's family for years. Both were also divorced, and Lona had her daughter Sepideh.

Lona and Pari were eager to assist me in any way they could. From a working-class family in Tabriz, they had lots of questions about America: What kind of food do we eat? Do women always wear short skirts? Is everyone tall and blond? Extremely hard workers, they didn't like to see me perform mundane personal chores, like cleaning my room or doing my own laundry, and they cooked elaborate dishes from their home province of Azerbaijan every night, even after spending long afternoons at the office: tahchin-e morgh, a baked chicken-and-rice dish with a crispy crust on top; kuku-ye sabzi, a richly textured omelet, thick with herbs; and kufteh tabrizi, Tabriz-style meatballs, made with prunes and apricots.

Lona, the older sister, had a flawless oval brown face with large almond eyes and lustrous black hair. Practical and self-confident, she seemed capable of handling virtually any situation; woe to the shopkeeper, I thought on more than one occasion, who tried to pull one over on her. She had a firm opinion on most subjects, sometimes raising her voice to shrill decibels, and an elegant taste that ran to small earrings and slim pieces of jewelry. Pari, in contrast, had a chalk-white complexion, sparkling black eyes, and striking dark eyebrows. She rarely spoke and occasionally seemed nervous. Her taste ran more to the dramatic. The sisters, however, shared a bubbling sense of humor and laughed easily, while Sepideh -- a serious child at the top of her class -- and I often looked on in mute incomprehension.

Bahman reigned over us women like a benevolent Turkic Persian prince. A short, handsome, and extremely kind man with a heavy mane of white hair, he was also originally from Tabriz, where most people are of a Turkic extraction and speak the Azeri Turkish language. Now a well-known gynecologist, he had been forced to flee Iran during the Islamic Revolution. His English wife, many Christian friends, and good income had made him an obvious probable target of the zealous revolutionaries, and he'd departed the country soon after finding the words Dr. Faratian must die written over his office door. He'd returned to Iran only in 1993, at the behest of the Iranian government, who'd extended its invitation to many other expatriated professionals as well. Bahman was one of the few who'd taken the government up on its offer. He'd had a more than comfortable life in England, he told me, but Iran was his country and he wanted to help his people.

Bahman's return to Iran gave him special status both in the community and among government officials, but he was nonetheless in an awkward position. While in England, he'd been part of the infertility team that had developed the world's first in vitro fertilizations. His return to Iran had been especially welcomed because he could bring with him the latest infertility techniques and introduce them to his colleagues. But men are no longer allowed to train as gynecologists in Iran -- Islamic law forbids it -- and so Bahman was one of a dying breed. All those who attended his lectures were women, and some of those women resented his gender. Some of his techniques, such as artificial insemination, were also highly problematic at first. In a traditional Islamic society, a woman can become legally pregnant only by her husband. Artificial insemination is therefore not allowed, and during his first years back, Bahman had had to obtain a special decree from Supreme Leader Khamene'i himself whenever he'd wanted to perform the procedure.

Bahman talked about my father as a young man in a way that made me catch my breath. He remembered how my father had paced before he was to perform an operation, reviewing human anatomy in his head, and how he'd studied his patients' hands for clues as to their illnesses. He remembered several field trips the two of them had taken together and could still imitate my father's cramped signature perfectly, down to the dashing F and illegible -ird. My father has always talked about Bahman with a great deal of fondness, but I knew that he didn't remember him in such detail. To my father, then already an accredited doctor from a powerful country, Bahman had been just a student 10 years his junior. To Bahman, the son of a bus driver from a provincial city, my father had been a learned man, representing the then seemingly omnipotent, technically advanced West. Now, though, it was Bahman who was the famous physician.

Despite the wealth of Bahman's neighborhood, it -- like much of Tehran -- had a cluttered, ragged, unfinished feel. Many of its new apartment buildings sported ersatz resortlike facades, only vaguely protected by flimsy walls that seemed to mock the old Persian ideal of hiding one's home behind thick clay bulwarks. Construction was going on in many of the streets, few of which had sidewalks, and cranes sat like dozing vultures atop at least a half-dozen buildings. Many of these cranes never moved an inch during my stay; running out of money while building is not unusual in inflation-rife Iran.

Along the short, dusty road that descended from Bahman's apartment to the main street ran a jube, or concrete water channel. During the spring, when the snow melts in the Alborz Mountains, or after a rain, the jube fills with water that then travels downstream to the city center. My parents had told me stories about the jubes and how in their time they'd been used both for washing clothes and as sewers, and so I was surprised to see them in the wealthy north. But water is a precious commodity in Iran -- the average rainfall is only 12 inches a year -- and jubes, I later found out, still line many of Tehran's main streets, where they sometimes join with surfacing underground streams. Some of these rushing waterways are three or four feet wide, and I often saw boys playing in them.

A jube had run outside our home in Tabriz, I remembered then in a flash, but our parents had never let us get near it, let alone play in it. Not surprisingly, they'd been worried about disease. But we had had two white-and-tan "jube dogs" -- as the strays were called -- as pets, much to the horror of our Iranian servants. Generally speaking, traditional Iranians do not keep dogs as pets. They regard them as unclean.

By the side of the road one block south of Bahman's apartment was a blue box cupped with painted yellow hands, with a plywood dove on top. It sat on a post about three feet tall and had a slit for money. ALMS MAKE YOU RICHER AND TO GIVE ALMS IS TO PROTECT YOURSELF AGAINST SEVENTY KINDS OF EVIL EYES read words stenciled on the sides. To give money to the poor is one of the five basic tenets of Islam, and thousands upon thousands of donation boxes fleck the Iranian landscape. Most of the boxes are a standard, machine-made blue and yellow, with a plywood dove, rose, or tulip on top, but I also noticed several homemade-looking versions. Iranians take their obligation of giving very seriously, and people often stop to push faded bills into the money slots. The proceeds go to the Helping Committee of Imam Khomeini, a charity organization that was set up following the Revolution to provide services for the poor. Charitable foundations in Iran have a widespread reputation for mind-boggling corruption -- said to run into many millions of dollars -- but they are at least somewhat effective: I saw relatively few beggars in the Islamic Republic.

Two blocks south of Bahman's apartment stood a cluster of small gaping shops selling dry goods, vegetables, and meat. The shops had rolling iron grills for doors and sold a mix of Iranian and European wares -- Lux, Mazola, Bic, Crest, Nescafé. Next door stood a bakery, dark, ancient, and hot, with a red fire roaring in a clay oven in the back and flour-dusted men tossing balls of dough up front. They were making sangak, one of four kinds of Persian flat bread, which is stretched out into the shape of an elongated pizza and baked until it is brown and bumpy on top. Most Iranians buy their bread fresh every day, and wherever I traveled in the country, I passed boys on bicycles, pedaling home with limp slabs of bread big as tabloid newspapers draped across their handlebars.

Actual newspapers and magazines were sold from a kiosk in front of the neighborhood shops. Among the dozens offered were the three English-language newspapers published in Tehran -- Iran News, Tehran Times, and Iran Daily -- and the international editions of Time and Newsweek, sold in sealed cellophane wrappers. The magazines' text was never censored, but all photos that were deemed offensive -- those depicting women with cleavage or women with exposed hair, arms, or legs -- were blacked out with a marker.

The three English-language newspapers were slim affairs, published primarily for Iran's diplomatic and Western-educated communities. Tehran Times was put out by Kayhan, a well-established, hard-line newspaper; Iran Daily was supported by the moderates; and Iran News straddled the philosophical difference between the two. Or so I was told, because in reality I could see only minor differences among the publications, all of which usually supported government policy.

For more controversial news coverage, I would have had to go to the Persian-language newspapers, which, unfortunately, I couldn't read. I was in Iran during a remarkable flowering of the press. In the year and a half following Khatami's election, the number of newspapers published in the country had more than quadrupled, until they numbered over 120. Most popular among them during my visit were Hamshahri, supported by Tehran's former mayor, the then recently ousted Gholam-Hosein Karbaschi, and Tus, supported by President Khatami. In Iran, newspapers are financed not through advertising and circulation but rather by political parties or organizations.

Every morning along major streets and highways, I saw vendors waving copies of Hamshahri and Tus, which citizens rushed to buy. Though there had been some muted freedom of the press in the Islamic Republic since the early 1990s, newspapers at the time of my visit were publishing stories that openly criticized the government and/or exposed some of Iran's many social problems. Hamshahri took a cautious approach, but Tus was frighteningly bold. They're going too far, people whispered among themselves, and they were right. Tus was closed down numerous times just before, during, and after my stay -- only to be started up again and again under different names. Repression in Iran is far from absolute, and the "new" papers were usually allowed to keep the "old" paper's address, printing presses, and staff. Finally, however, in November 1999, the newspaper's editor, Mashallah Shamsolva'ezin, was put on trial and sentenced to 30 months in prison.

North Tehran backs up into the embrace of the Alborz Mountains, the most defining physical characteristic of the city. Bone dry and nearly devoid of vegetation in many parts, the Alborz are a living, breathing, shape-shifting presence that seems to stretch, yawn, buckle, and bend as it looms over the metropolis like a giant elephant in repose. One unexpected jerk in the middle of its usually protective sleep and it could kick the entire city right out of its foothills.

Sometimes the Alborz -- as high as the American Rockies -- are all ridges, valleys, rocks, and sand, with sunlight illuminating a hidden cliff here, an unexpected rockslide there. Sometimes the Alborz are a flat, impenetrable, dun-colored wall, separating Tehran -- and by extension, it seems, all of Iran -- from the rest of the world. Sometimes the Alborz are sensual, red-hued, and comforting. Sometimes the Alborz are craggy, black, and forbidding.

Sensitive to every nuance of light and atmosphere, the Alborz subtly change color with the day. Though often a dull gray or maroon at first glance, closer looks reveal shifting green streaks, pink splotches, and purple peaks. A cloud passes over, casting down a blue patch.

On especially sunny days in north Tehran, the light of the Alborz reminded me of the light of my early childhood. This was the same stark backdrop across which my memories were moving. The air was buoyant, the slopes bleak.

On other days, though, as I wandered through the heart of the downtown, I would forget all about the mountains -- often rendered close to invisible by horrendous pollution. Along with Mexico City and Bangkok, Tehran is one of the most polluted cities in the world. But then a ray of sunlight would glance off a snowy peak or the sense of a powerful presence would make me look up. And then, there they were again, the Alborz, which have haunted Iran's consciousness since its very beginnings.

The ancient Persians believed that the Alborz grew from the surface of the earth, taking 800 years to reach their full height, as their roots reached deep into the ground and their peaks attached themselves to the sky. The stars, sun, and moon were thought to revolve around these peaks, and they became the mythological home of Mithra, the god of the cosmic order who later became known as the sun god in both Iran and India. Mithra and the creation of the Alborz are described in the Avesta, the holy book of the Zoroastrian religion. An ancient faith, founded in what is now Iran between 1000 and 700 B.C., Zoroastrianism was the first known belief system to posit the concepts of life as a perennial struggle between good and evil, individual responsibility for moral behavior, the resurrection of the body, the Last Judgment, and life everlasting. Islam, Judaism, and Christianity all trace many articles of their faiths back to Zoroastrianism.

To the east of Tehran, and visible only from certain angles of the city, is the Alborz's highest peak, Mount Damavand (18,602 feet). A magnificent cone-shaped volcano that is perpetually covered with snow, Mount Damavand is to Iran what Mount Fuji is to Japan and Kilimanjaro is to Tanzania.

Mount Damavand is home to many legendary Persian figures, including the magical bird Simorgh, whose nest is said to be close to the sun, and the evil ruler Zahhak, who is living out eternity bound in chains at the bottom of a well deep inside the mountain. Though a hero as a youth, Zahhak was seduced by the devil, who exploited his ignorance of evil and talked him into murdering his father. In return, promised the devil, Zahhak would become not only ruler of his father's lands but also ruler of all the world. As soon as the pact was made, two black snakes suddenly sprouted out of Zahhak's shoulders. He cut off their heads, but they instantly grew back again and demanded to be fed the brains of two strong men every day. Thereafter began a reign of terror that lasted for 1,000 years, until the arrival of Fereydun, a youth as tall and slim as a cypress tree, with a face as fair as the silver moon. Born in a village on Mount Damavand, Fereydun struck Zahhak with a bull-headed mace and was about to cut off his head when an angel appeared and told him to lock Zahhak inside the mountain instead, as a warning to all future men. Fereydun did so, and there Zahhak lives to this day.

A sort of modern-day equivalent of Zahhak is the notorious Evin prison, situated in the soft brown foothills of the Alborz on the northwestern edge of the city. Once part of a suburb, Evin now belongs to Tehran proper and is only a short distance away from the sleek, luxurious Azadi Grand Hotel, many of whose rooms overlook the prison. Azadi means "freedom," but when I commented on the obvious irony of its name to my new Iranian friends, they just shrugged. In Iran, people are used to living beside the absurd.

While in Tehran, I passed by Evin prison nearly every day on my way downtown from Bahman's. From the outside, it looked tame and innocuous. Serrated brown walls zigzagged their way up one hillside to disappear into a valley behind, and to reappear again on the far hillside. Inside the walls, the prison appeared to be largely empty space -- I caught only occasional glimpses of buildings resembling dormitories and sheds. But at night, everything changed. Bright, hot prison spotlights flicked on, reminding me in one suffocating instant of Evin's horrific history.

During the reign of the Shah, the prison was the stronghold of SAVAK, the ruthless secret police trained by the American CIA and the Israeli Mossad, and after the revolution, thousands of political prisoners were tortured and others put to death there. Today's version of SAVAK, SAVAMA, has nothing approaching the zealous reputation of its predecessor, thought by various human rights organizations to have held between 25,000 and 100,000 Iranians political prisoner in the mid-1970s. However, whereas SAVAK concentrated primarily on political dissidents, SAVAMA keeps tabs on the most mundane details of ordinary citizens' lives. And there are still far too many stories of men and women disappearing into Evin's bowels for inexplicable reasons and unspecified periods of time. For the year that I was in Iran, Amnesty International's annual report on the country read:

Hundreds of political prisoners, including prisoners of conscience, were held. Some were detained without charge or trial; others continued to serve long prison sentences imposed after unfair trials. Reports of torture and ill-treatment continued to be received and judicial punishments of flogging and stoning continued to be imposed....Scores of people were reportedly executed, including at least one prisoner of conscience; however, the true number may have been considerably higher.

"Da-da-da-da-da-da, da-da-da-da-da-da -- " I was on hold with the Foreign Correspondents and Media Department of the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. It took me a moment to place the jingly tune I was listening to, but when I did, I started -- and would have laughed, had I not been so nervous. Scott Joplin's "The Entertainer," here in the Islamic Republic of Iran, which throughout most of the 1980s had banned all popular Western and Persian music from its airwaves. I knew that things had eased up considerably since then, but I still hadn't expected to hear American ragtime music coming from the offices of a government organization. Somehow, it seemed even more surprising to me than the illegal Michael Jackson and Pink Floyd tapes I'd already heard blaring out of taxi cabs.

A Mr. Ali Reza Shiravi came on the line. Yes, he and his colleagues were expecting me. Please be in his office the next morning at 10:00.

I hung up, almost trembling. Someone had already called Bahman earlier that morning to confirm that I was staying with him, as I'd claimed on my entrance papers. And now I was about to meet with the government officials who would be keeping tabs on me during my stay in Iran. I had no idea whether they'd help or hinder my travels, but I expected the worst.

Established shortly after the revolution, the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance is ubiquitous in Iran. Referred to simply as Ershad, or Guidance, by most Iranians, it monitors virtually every aspect of life in Iran, with the intent -- as its name implies -- of upholding Islamic standards. Among many other things, Ershad censors the media; decides what films, plays, art exhibits, and concerts can be produced; establishes the educational curricula of schools and universities; organizes the tourism industry, including pilgrimages to Mecca; and monitors financial and judicial institutions.

I arrived at one of Ershad's many branches shortly before 10:00 the next morning. My heart was racing and my throat was dry -- Just why was it again that I'd wanted to come to Iran? I half asked myself. A grim bearded man at the entrance waved me toward an elevator, and I rode up to the sixth floor, nearly tripping over my manteau as I exited its narrow confines. Once I was inside the Foreign Correspondents Department, however, a woman in a chador welcomed me with an application form and a smile that put me somewhat more at ease.