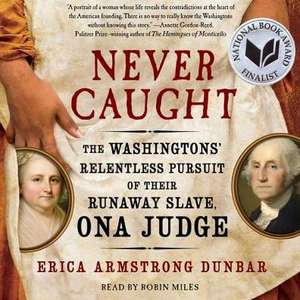

Never Caught: The Washingtons' Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge

Autor Erica Armstrong Dunbar Robin Milesen Limba Engleză CD-Audio – 22 oct 2018

When George Washington was elected president, he reluctantly left behind his beloved Mount Vernon to serve in Philadelphia, the temporary seat of the nation’s capital. In setting up his household he brought along nine slaves, including Ona Judge. As the President grew accustomed to Northern ways, there was one change he couldn’t abide: Pennsylvania law required enslaved people be set free after six months of residency in the state. Rather than comply, Washington decided to circumvent the law. Every six months he sent the slaves back down south just as the clock was about to expire.

Though Ona Judge lived a life of relative comfort, she was denied freedom. So, when the opportunity presented itself one clear and pleasant spring day in Philadelphia, Judge left everything she knew to escape to New England. Yet freedom would not come without its costs. At just twenty-two-years-old, Ona became the subject of an intense manhunt led by George Washington, who used his political and personal contacts to recapture his property.

“A crisp and compulsively readable feat of research and storytelling” (USA TODAY), historian and National Book Award finalist Erica Armstrong Dunbar weaves a powerful tale and offers fascinating new scholarship on how one young woman risked everything to gain freedom from the famous founding father and most powerful man in the United States at the time.

Preț: 168.89 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 253

Preț estimativ în valută:

28.51€ • 29.85$ • 23.59£

28.51€ • 29.85$ • 23.59£

Indisponibil temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781508281634

ISBN-10: 1508281637

Dimensiuni: 147 x 142 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.14 kg

Editura: Simon & Schuster Audio

ISBN-10: 1508281637

Dimensiuni: 147 x 142 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.14 kg

Editura: Simon & Schuster Audio

Notă biografică

Erica Armstrong Dunbar is the Charles and Mary Beard Professor of History at Rutgers University. Her first book, A Fragile Freedom: African American Women and Emancipation in the Antebellum City, was published by Yale University Press in 2008. Her second book, Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge was a 2017 finalist for the National Book Award in nonfiction and a winner of the 2018 Frederick Douglass Book Award. She is also the author of She Came to Slay, an illustrated tribute to Harriet Tubman, and Susie King Taylor and is the co-executive producer of the HBO series The Gilded Age.

Extras

Never Caught

![]()

List of slaves at Mount Vernon, 1799. Courtesy of Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association.

In June of 1773, the unimaginable happened: it snowed in Virginia.

During the first week of June, the typical stifling heat that almost always blanketed Virginia had not yet laid its claim on the colony. Daytime temperatures fluctuated from sultry warmth to a rainy chill during the first few days of the month. Even more peculiar yet, on June 11, it snowed. As he did most days, Colonel George Washington sat down and recorded the unusual weather, writing, “Cloudy & exceeding Cold Wind fresh from the No. West, & Snowing.” His diary went on to note, “Memorandum—Be it remembered that on the eleventh day of June in the year one thousand seven hundred and seventy three It rain’d Hail’d snow’d and was very Cold.”

![]()

The men and women who lived on George and Martha Washington’s estate must have marveled at the peculiar snow, but whatever excitement the unusual weather brought was most certainly replaced by concern. Shabby clothing and uninsulated slave cabins turned winter into long periods of dread for the enslaved men and women at Mount Vernon and across the colony of Virginia. Although the intense heat of summer brought its own difficulties, winter brought sickness, long periods of isolation, and heightened opportunities for the auction block. To exacerbate matters, the selling of slaves frequently occurred at the beginning of the year, connecting the winter month of January to a fear of deep and permanent loss. The snow in June, then, could only be a sign of very bad things to come. For the nearly 150 slaves who labored on the Mount Vernon estate in 1773, a mixture of superstition, African religious practices, and English beliefs in witchery must have intensified a sense of fear. Things that were inconsistent with nature were interpreted as bad omens, commonly bringing drought, pestilence, and death. As for what this snow portended, only time would tell.

Sure enough, eight days after the snow fell, Martha Parke Custis, daughter of Martha Washington, fell terribly ill. The stepdaughter of George Washington, just seventeen, had long struggled with a medical condition that rendered her incapable of controlling her body. Plagued by seizures that began during her teenage years, “Patsy” Custis most likely suffered from epilepsy. The early discipline of medicine was far from mature, offering few options for cures outside of bleeding and purges. Her parents had spent the last five years consulting with doctors and experimenting with unhelpful medicinal potions, diet, exercise modifications, and of course, deep prayer.

Their faith was tested on June 19 when Patsy Custis and a host of invited family members were finishing up with dinner a little after four o’clock. Although sickly, Washington’s stepdaughter had been “in better health and spirits than she appeared to have been in for some time.” After dinner and quiet conversation with family, Patsy excused herself and went to retrieve a letter from her bedroom. Eleanor Calvert, Patsy’s soon-to-be sister-in-law, went to check on the young woman and found her seizing violently on the floor. Patsy was moved to the bed, but there was very little anyone could do. Within two minutes, she was gone.

The June snow and Patsy’s death combined to create an eerie feeling of uncertainty. House slaves understood that Martha Washington would need to be handled with more care than usual, especially since this was not the first child that she had lost. Two of her toddlers had succumbed to the high childhood mortality rates of colonial Virginia, and Patsy’s death left the devastated mother with only one living child. George Washington wrote to his nephew, breaking the news of his stepdaughter’s death and his wife’s emotional distress, stating, “I scarce need add [that Patsy’s death] has almost reduced my poor Wife to the lowest ebb of Misery.” George Washington wasn’t the only one attuned to Martha’s emotional state. Slave women who worked in the Mansion House tended to the devastated Martha Washington, taking great care to respect their grieving mistress, while helping the household prepare for Patsy’s funeral.

Yet while the mistress Martha Washington wept over the loss of her daughter, a slave woman named Betty (also known as Mulatto Betty) prepared for an arrival of her own. Born sometime around 1738, Betty was a dower slave; that is, she was “property” owned by Martha Washington’s first husband, Daniel Parke Custis. As a seamstress and expert spinner who was among Mrs. Washington’s favored slaves, the bondwoman had a long history with her mistress, one that predated the relationship between Colonel Washington and his wife and one that had seen Martha endure great heartbreak. In 1757 Betty watched her mistress survive the sudden loss of her first husband, followed by the death of her four-year-old daughter, Frances. She also watched Martha reemerge from sorrow’s clutch. Betty continued to spin and sew as her mistress took control of the family business, which included six plantations and close to three hundred slaves that fed Virginia’s tobacco economy. With the death of her husband, Martha Parke Custis stood in control of over 17,500 acres of land, making her one of the wealthiest widows in the colony of Virginia, if not throughout the entire Chesapeake.

Before her move to Mount Vernon, Betty worked in the Custis home known as the White House on the Pamunkey River in New Kent County, Virginia. Two years after the death of her owner, Betty learned that her mistress was to remarry. She most likely received the news of her mistress’s impending second marriage with great wariness as word spread that Martha Custis’s intended was Colonel George Washington. The colonel was a fairly prominent landowner with a respectable career as a military officer and an elected member of the Virginia House of Burgesses. His marriage to the widowed Martha Custis would offer him instant wealth and the stability of a wife and family that had eluded him. For her part, the young widow had managed to secure a surrogate father to help raise her two living children. She had also found a partner with whom she could spend the rest of her days. Nevertheless, a huge yet necessary transition awaited Martha Custis as she prepared to marry and move to the Mount Vernon estate, nearly one hundred miles away.

For Betty, as well as the hundreds of other slaves that belonged to the Custis estate, the death of their previous owner and Martha’s marriage to George Washington was a reminder of their vulnerability. It was often after the death of an owner that slaves were sold to remedy the debts held by an estate. Betty and all those enslaved at New Kent had no idea what kind of financial transactions would transpire, which families would be split apart, never to be united again. For enslaved women, the moral character of the new owner was also a serious concern. When George and Martha Washington married in January of 1759, Betty was approximately twenty-one years old and considered to be in the prime of her reproductive years. She was unfamiliar with her new master’s preferences, or more importantly, if he would choose to exercise his complete control over her body. All of the enslaved women who would leave for Mount Vernon most likely worried about their new master’s protocol regarding sexual relations with his slaves. But of greater consequence for Betty was the future for her young son, Austin. Born sometime around 1757, Austin was a baby or young toddler when his mistress took George Washington’s hand in marriage. To lose him before she even got to know him, to have joined the thousands who stood by powerlessly while their children were “bartered for gold,” as the poet Frances Ellen Watkins Harper wrote, would have been devastating.

![]()

As she prepared to move to Mount Vernon, Martha Washington selected a number of slaves to accompany her on the journey to Fairfax County. Betty and Austin were, to Betty’s relief, among them. The highest-valued mother-and-child pair in a group that counted 155 slaves, they arrived in April of 1759.

Betty managed to do what many slave mothers couldn’t: keep her son. Austin’s very young age would have prohibited the Custis estate from fetching a high price if he were sold independently from his mother. Perhaps this fact, in addition to Betty’s prized position in the Custis household, ensured that she would stay connected to her child as she moved away from the place she had called home.

As Martha Washington settled into her new life with her second husband at Mount Vernon, a sprawling estate consisting of five separate farms, Betty also adapted, continuing her spinning, weaving, tending to her son, and making new family and friends at the plantation. The intricacies of Betty’s romantic life at Mount Vernon remain unclear, but what we do know is that more than a decade after giving birth to Austin, Betty welcomed more children into the world. Her son, Tom Davis, was born around 1769, and his sister Betty Davis arrived in 1771. Unlike Austin, these two children claimed a last name, one that most likely linked them to a hired white weaver named Thomas Davis.

George and Martha Washington placed their most “valued” and favored slaves inside the household. Martha Washington allowed only those slaves she felt to be the most polished and intelligent to toil within the walls of the main house, and that included Betty, whose skills as a clothier ranged from knowledge of expert weaving to the dyeing of expensive and scarce fabric. Betty and a corps of talented enslaved seamstresses not only outfitted their masters but also stitched together clothing for the hundreds of slaves at Mount Vernon.

Now, in 1773, fourteen years after she watched her mistress experience the death of her first child, Betty witnessed her mistress come undone once again. The loss of her daughter Patsy left Martha Washington almost inconsolable and stood in contrast with Betty’s relative good fortune. Martha Washington had lost young Frances in 1759, just as Betty was blessed with the arrival of her son Austin. Now, the circumstances were nearly identical, for as Martha Washington grieved over the loss of her daughter, Betty began preparing for the arrival of another child. June snow served as a marker of death for the Washingtons but issued a very different signal to Betty. It marked the beginning of a life that would be as unusual as summertime winter weather. Sometime around or after the June snow of 1773, Betty gave birth to a daughter named Ona Maria Judge. This girl child would come to represent the complexity of slavery, the limits of black freedom, and the revolutionary sentiments held by many Americans. She would be called Oney.

Betty, like other bondwomen, increased her owner’s wealth each time she bore a child. Although she called George Washington her master, he owned neither Betty nor her children. As a dower slave, Betty was technically owned by Martha Washington and the Custis estate. The birth of Ona Judge would not add value to George Washington’s coffers, but her body would be counted among the human property that would produce great profit for Martha Washington and the Custis children and grandchildren.

Similar to Betty’s other children, Ona had a surname. It belonged to her father, Andrew Judge, an English-born white man. On July 8, 1772, Andrew Judge found his way to America via an indenture agreement, contracting himself to Alexander Coldelough, a merchant from Leeds, England. In exchange for his passage to “Baltimore or any port in America” as well as a promise of food, clothing, appropriate shelter, and an allowance, Judge handed over four years of his life. Although indentured servitude served as the engine for population growth in the early seventeenth century, Andrew Judge entered into service at a time when fewer and fewer English men agreed to hand over their lives for an opportunity in the colonies. Why did he come? Indenture agreements never made clear the circumstances from which a person was exiting, so it is quite possible that Judge was running from debt or a life of destitution. Whatever the problem, the solution for Judge was life as a servant in the colonies, uncertainty and all.

He landed in Alexandria, Virginia, where George Washington purchased his indenture for thirty pounds. Mount Vernon relied primarily upon slave labor; however, Washington included a number of white indentured servants in his workforce. White servitude had its advantages, but by the late eighteenth century, planters like Washington often complained about their unreliability, their tendency for attempted escape, and their laziness. Yet Andrew Judge did not appear as the target of Washington’s ire in any of his correspondence. In fact he became a trusted tailor relied upon by the colonel for outfitting him at the most important of moments. By 1774 he appeared in the Mount Vernon manager’s account book as responsible for creating the blue uniform worn by Washington when he was named commander in chief of the American forces. Judge was responsible for making clothing for the entire Washington family, which would have required him to make frequent visits to the main house, where he would come into contact with Betty. In her mid- to late thirties, Betty became acquainted with the indentured tailor.

Interracial relationships were far from uncommon in Virginia at the time, and many mixed-race children were counted among the enslaved. Perhaps Betty and Andrew Judge flirted with one another, eventually engaging in a mutual affair. Maybe the two bound laborers fell in love. If either of these scenarios were true, Betty probably chose her lover, a most powerful example of agency in the life of an enslaved woman. Understanding the inherited status of slavery, Betty would have known that any child born to her would carry the burden of slavery, that any child she bore would be enslaved. Nonetheless, a union with Andrew Judge could facilitate a road to emancipation for their child and perhaps for Betty herself. Eventually Judge would work through his servitude agreement and become a free man. If he saved enough money, he could offer to purchase his progeny, as well as Betty and her additional children. Although a legal union in Virginia between a white man and a black woman would not be recognized for almost two centuries, Judge’s eventual rise in status out of the ranks of servant to that of a free, landholding, white man offered potential power. Andrew Judge may not have been able to marry Betty, but if he loved her, he could try to protect her and her family from the vulnerability of slavery.

Love or romance, however, may not have brought the two bound laborers together. Although he was a servant, Andrew Judge was a white man with the power to command or force a sexual relationship with the enslaved Betty. What is lost to us is just how consensual their relationship may have been. Perhaps Judge stalked Betty, eventually forcing himself upon her. As a black woman, she would have virtually no ability to protect herself from unwanted advances or sexual attack. The business of slavery received every new enslaved baby with open arms, no matter the circumstances of conception. What we do know is that their union, whether brief or extended, consensual or unwanted, resulted in the birth of a daughter. We also know that however Judge defined his relationship to his daughter, it wasn’t enough to keep him at Mount Vernon.

Eventually Andrew Judge left and built upon the opportunity that indentured servitude promised. By the 1780s Andrew Judge lived in his own home in Fairfax County. Listed among the occupants of his home were six additional residents, one of whom was black. It’s uncertain if Andrew Judge owned a slave or if he simply hired a free black person who lived on and worked his land. What is clear from the evidence left behind is that Judge left Mount Vernon and his enslaved daughter behind. Perhaps he attempted to purchase Betty and his child but was refused the opportunity by the Washingtons. Or maybe Judge simply didn’t want a complicated relationship with an enslaved woman and a mixed-race daughter. Whatever hope, if any, Betty had placed upon the relationship with Andrew Judge collapsed quickly, leaving her at Mount Vernon to raise Ona and her siblings, including Philadelphia, a daughter she gave birth to after Ona but before Judge left, sometime around 1780.

Leaving his child behind at Mount Vernon, Andrew Judge’s parting gift to his daughter was a surname and a unique first name. The name is both African and Gaelic, and no other slave at Mount Vernon or the White House on the Pamunkey River was named Ona. Perhaps even more exceptional was that she was given a middle name, Maria. Her distinctive name set her apart from her siblings and from the majority of the other bondmen and bondwomen who toiled with her in Virginia.

![]()

The slaves who were directly connected to the work at the Mansion House lived across the road from the blacksmith’s forge in the communal space known as the Quarters, or House for Families. Betty and other women who worked in the Mansion House were typically required to be present from sunrise to sundown, preparing meals, mending clothes, cleaning, spinning, and performing other domestic tasks, leaving most enslaved children separated from their parent or parents most of the day. Many of the children at Mount Vernon began structured labor between the ages of nine and fourteen, but most performed odd jobs just as soon as they were physically able. As very young enslaved children were unhelpful and sometimes considered a nuisance, they were often left in the Quarters without much supervision beyond the older slave women, who were deemed incapable of working in the fields and no longer up to the task of domestic work.

Bushy haired, with light skin and freckles, a young Ona probably spent some of her days playing with her siblings and other enslaved children in the Quarters. More often than not, though, she had to learn how to fend for herself. Judge and the other children at Mount Vernon cried out in loneliness for their parents, witnessed the brutality of whippings and corporal punishment, and fell victim to early death due to accidental fires and drowning. Childhood for enslaved girls and boys was fleeting and fraught with calamity. Many perished before reaching young adulthood. Judge’s childhood wasn’t shortened by a plantation fatality. Instead, hers ended at age ten, when she was called to serve Martha Washington up at the Mansion House.

A good number of children at Mount Vernon did not live with both of their parents, a circumstance created by the separation of enslaved spouses. Washington may not have broken up slave marriages by selling away husbands and wives, but he was not averse to separating slave couples by placing them on different farms. While he may not have purposefully disrupted slave unions, the business of slavery and the needs of Mount Vernon always came first. For slave couples and enslaved families, this meant that they would see each other only when permission was given.

Just like other enslaved children, Ona Judge did not spend the majority of her youth with two parents. Andrew Judge had the privilege of white skin and the power anchored in a male body that allowed him to slip away from a life of unpaid labor. Betty had neither gender nor race on her side, and spent the entirety of her life in human bondage in Virginia, a colony that would eventually become the slave-breeding capital of a new nation. Ona Judge learned valuable lessons from both of her parents. From her mother she would learn the power of perseverance. From her father, Judge would learn that the decision to free oneself trumped everything, no matter who was left behind.

One

Betty’s Daughter

List of slaves at Mount Vernon, 1799. Courtesy of Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association.

In June of 1773, the unimaginable happened: it snowed in Virginia.

During the first week of June, the typical stifling heat that almost always blanketed Virginia had not yet laid its claim on the colony. Daytime temperatures fluctuated from sultry warmth to a rainy chill during the first few days of the month. Even more peculiar yet, on June 11, it snowed. As he did most days, Colonel George Washington sat down and recorded the unusual weather, writing, “Cloudy & exceeding Cold Wind fresh from the No. West, & Snowing.” His diary went on to note, “Memorandum—Be it remembered that on the eleventh day of June in the year one thousand seven hundred and seventy three It rain’d Hail’d snow’d and was very Cold.”

The men and women who lived on George and Martha Washington’s estate must have marveled at the peculiar snow, but whatever excitement the unusual weather brought was most certainly replaced by concern. Shabby clothing and uninsulated slave cabins turned winter into long periods of dread for the enslaved men and women at Mount Vernon and across the colony of Virginia. Although the intense heat of summer brought its own difficulties, winter brought sickness, long periods of isolation, and heightened opportunities for the auction block. To exacerbate matters, the selling of slaves frequently occurred at the beginning of the year, connecting the winter month of January to a fear of deep and permanent loss. The snow in June, then, could only be a sign of very bad things to come. For the nearly 150 slaves who labored on the Mount Vernon estate in 1773, a mixture of superstition, African religious practices, and English beliefs in witchery must have intensified a sense of fear. Things that were inconsistent with nature were interpreted as bad omens, commonly bringing drought, pestilence, and death. As for what this snow portended, only time would tell.

Sure enough, eight days after the snow fell, Martha Parke Custis, daughter of Martha Washington, fell terribly ill. The stepdaughter of George Washington, just seventeen, had long struggled with a medical condition that rendered her incapable of controlling her body. Plagued by seizures that began during her teenage years, “Patsy” Custis most likely suffered from epilepsy. The early discipline of medicine was far from mature, offering few options for cures outside of bleeding and purges. Her parents had spent the last five years consulting with doctors and experimenting with unhelpful medicinal potions, diet, exercise modifications, and of course, deep prayer.

Their faith was tested on June 19 when Patsy Custis and a host of invited family members were finishing up with dinner a little after four o’clock. Although sickly, Washington’s stepdaughter had been “in better health and spirits than she appeared to have been in for some time.” After dinner and quiet conversation with family, Patsy excused herself and went to retrieve a letter from her bedroom. Eleanor Calvert, Patsy’s soon-to-be sister-in-law, went to check on the young woman and found her seizing violently on the floor. Patsy was moved to the bed, but there was very little anyone could do. Within two minutes, she was gone.

The June snow and Patsy’s death combined to create an eerie feeling of uncertainty. House slaves understood that Martha Washington would need to be handled with more care than usual, especially since this was not the first child that she had lost. Two of her toddlers had succumbed to the high childhood mortality rates of colonial Virginia, and Patsy’s death left the devastated mother with only one living child. George Washington wrote to his nephew, breaking the news of his stepdaughter’s death and his wife’s emotional distress, stating, “I scarce need add [that Patsy’s death] has almost reduced my poor Wife to the lowest ebb of Misery.” George Washington wasn’t the only one attuned to Martha’s emotional state. Slave women who worked in the Mansion House tended to the devastated Martha Washington, taking great care to respect their grieving mistress, while helping the household prepare for Patsy’s funeral.

Yet while the mistress Martha Washington wept over the loss of her daughter, a slave woman named Betty (also known as Mulatto Betty) prepared for an arrival of her own. Born sometime around 1738, Betty was a dower slave; that is, she was “property” owned by Martha Washington’s first husband, Daniel Parke Custis. As a seamstress and expert spinner who was among Mrs. Washington’s favored slaves, the bondwoman had a long history with her mistress, one that predated the relationship between Colonel Washington and his wife and one that had seen Martha endure great heartbreak. In 1757 Betty watched her mistress survive the sudden loss of her first husband, followed by the death of her four-year-old daughter, Frances. She also watched Martha reemerge from sorrow’s clutch. Betty continued to spin and sew as her mistress took control of the family business, which included six plantations and close to three hundred slaves that fed Virginia’s tobacco economy. With the death of her husband, Martha Parke Custis stood in control of over 17,500 acres of land, making her one of the wealthiest widows in the colony of Virginia, if not throughout the entire Chesapeake.

Before her move to Mount Vernon, Betty worked in the Custis home known as the White House on the Pamunkey River in New Kent County, Virginia. Two years after the death of her owner, Betty learned that her mistress was to remarry. She most likely received the news of her mistress’s impending second marriage with great wariness as word spread that Martha Custis’s intended was Colonel George Washington. The colonel was a fairly prominent landowner with a respectable career as a military officer and an elected member of the Virginia House of Burgesses. His marriage to the widowed Martha Custis would offer him instant wealth and the stability of a wife and family that had eluded him. For her part, the young widow had managed to secure a surrogate father to help raise her two living children. She had also found a partner with whom she could spend the rest of her days. Nevertheless, a huge yet necessary transition awaited Martha Custis as she prepared to marry and move to the Mount Vernon estate, nearly one hundred miles away.

For Betty, as well as the hundreds of other slaves that belonged to the Custis estate, the death of their previous owner and Martha’s marriage to George Washington was a reminder of their vulnerability. It was often after the death of an owner that slaves were sold to remedy the debts held by an estate. Betty and all those enslaved at New Kent had no idea what kind of financial transactions would transpire, which families would be split apart, never to be united again. For enslaved women, the moral character of the new owner was also a serious concern. When George and Martha Washington married in January of 1759, Betty was approximately twenty-one years old and considered to be in the prime of her reproductive years. She was unfamiliar with her new master’s preferences, or more importantly, if he would choose to exercise his complete control over her body. All of the enslaved women who would leave for Mount Vernon most likely worried about their new master’s protocol regarding sexual relations with his slaves. But of greater consequence for Betty was the future for her young son, Austin. Born sometime around 1757, Austin was a baby or young toddler when his mistress took George Washington’s hand in marriage. To lose him before she even got to know him, to have joined the thousands who stood by powerlessly while their children were “bartered for gold,” as the poet Frances Ellen Watkins Harper wrote, would have been devastating.

As she prepared to move to Mount Vernon, Martha Washington selected a number of slaves to accompany her on the journey to Fairfax County. Betty and Austin were, to Betty’s relief, among them. The highest-valued mother-and-child pair in a group that counted 155 slaves, they arrived in April of 1759.

Betty managed to do what many slave mothers couldn’t: keep her son. Austin’s very young age would have prohibited the Custis estate from fetching a high price if he were sold independently from his mother. Perhaps this fact, in addition to Betty’s prized position in the Custis household, ensured that she would stay connected to her child as she moved away from the place she had called home.

As Martha Washington settled into her new life with her second husband at Mount Vernon, a sprawling estate consisting of five separate farms, Betty also adapted, continuing her spinning, weaving, tending to her son, and making new family and friends at the plantation. The intricacies of Betty’s romantic life at Mount Vernon remain unclear, but what we do know is that more than a decade after giving birth to Austin, Betty welcomed more children into the world. Her son, Tom Davis, was born around 1769, and his sister Betty Davis arrived in 1771. Unlike Austin, these two children claimed a last name, one that most likely linked them to a hired white weaver named Thomas Davis.

George and Martha Washington placed their most “valued” and favored slaves inside the household. Martha Washington allowed only those slaves she felt to be the most polished and intelligent to toil within the walls of the main house, and that included Betty, whose skills as a clothier ranged from knowledge of expert weaving to the dyeing of expensive and scarce fabric. Betty and a corps of talented enslaved seamstresses not only outfitted their masters but also stitched together clothing for the hundreds of slaves at Mount Vernon.

Now, in 1773, fourteen years after she watched her mistress experience the death of her first child, Betty witnessed her mistress come undone once again. The loss of her daughter Patsy left Martha Washington almost inconsolable and stood in contrast with Betty’s relative good fortune. Martha Washington had lost young Frances in 1759, just as Betty was blessed with the arrival of her son Austin. Now, the circumstances were nearly identical, for as Martha Washington grieved over the loss of her daughter, Betty began preparing for the arrival of another child. June snow served as a marker of death for the Washingtons but issued a very different signal to Betty. It marked the beginning of a life that would be as unusual as summertime winter weather. Sometime around or after the June snow of 1773, Betty gave birth to a daughter named Ona Maria Judge. This girl child would come to represent the complexity of slavery, the limits of black freedom, and the revolutionary sentiments held by many Americans. She would be called Oney.

Betty, like other bondwomen, increased her owner’s wealth each time she bore a child. Although she called George Washington her master, he owned neither Betty nor her children. As a dower slave, Betty was technically owned by Martha Washington and the Custis estate. The birth of Ona Judge would not add value to George Washington’s coffers, but her body would be counted among the human property that would produce great profit for Martha Washington and the Custis children and grandchildren.

Similar to Betty’s other children, Ona had a surname. It belonged to her father, Andrew Judge, an English-born white man. On July 8, 1772, Andrew Judge found his way to America via an indenture agreement, contracting himself to Alexander Coldelough, a merchant from Leeds, England. In exchange for his passage to “Baltimore or any port in America” as well as a promise of food, clothing, appropriate shelter, and an allowance, Judge handed over four years of his life. Although indentured servitude served as the engine for population growth in the early seventeenth century, Andrew Judge entered into service at a time when fewer and fewer English men agreed to hand over their lives for an opportunity in the colonies. Why did he come? Indenture agreements never made clear the circumstances from which a person was exiting, so it is quite possible that Judge was running from debt or a life of destitution. Whatever the problem, the solution for Judge was life as a servant in the colonies, uncertainty and all.

He landed in Alexandria, Virginia, where George Washington purchased his indenture for thirty pounds. Mount Vernon relied primarily upon slave labor; however, Washington included a number of white indentured servants in his workforce. White servitude had its advantages, but by the late eighteenth century, planters like Washington often complained about their unreliability, their tendency for attempted escape, and their laziness. Yet Andrew Judge did not appear as the target of Washington’s ire in any of his correspondence. In fact he became a trusted tailor relied upon by the colonel for outfitting him at the most important of moments. By 1774 he appeared in the Mount Vernon manager’s account book as responsible for creating the blue uniform worn by Washington when he was named commander in chief of the American forces. Judge was responsible for making clothing for the entire Washington family, which would have required him to make frequent visits to the main house, where he would come into contact with Betty. In her mid- to late thirties, Betty became acquainted with the indentured tailor.

Interracial relationships were far from uncommon in Virginia at the time, and many mixed-race children were counted among the enslaved. Perhaps Betty and Andrew Judge flirted with one another, eventually engaging in a mutual affair. Maybe the two bound laborers fell in love. If either of these scenarios were true, Betty probably chose her lover, a most powerful example of agency in the life of an enslaved woman. Understanding the inherited status of slavery, Betty would have known that any child born to her would carry the burden of slavery, that any child she bore would be enslaved. Nonetheless, a union with Andrew Judge could facilitate a road to emancipation for their child and perhaps for Betty herself. Eventually Judge would work through his servitude agreement and become a free man. If he saved enough money, he could offer to purchase his progeny, as well as Betty and her additional children. Although a legal union in Virginia between a white man and a black woman would not be recognized for almost two centuries, Judge’s eventual rise in status out of the ranks of servant to that of a free, landholding, white man offered potential power. Andrew Judge may not have been able to marry Betty, but if he loved her, he could try to protect her and her family from the vulnerability of slavery.

Love or romance, however, may not have brought the two bound laborers together. Although he was a servant, Andrew Judge was a white man with the power to command or force a sexual relationship with the enslaved Betty. What is lost to us is just how consensual their relationship may have been. Perhaps Judge stalked Betty, eventually forcing himself upon her. As a black woman, she would have virtually no ability to protect herself from unwanted advances or sexual attack. The business of slavery received every new enslaved baby with open arms, no matter the circumstances of conception. What we do know is that their union, whether brief or extended, consensual or unwanted, resulted in the birth of a daughter. We also know that however Judge defined his relationship to his daughter, it wasn’t enough to keep him at Mount Vernon.

Eventually Andrew Judge left and built upon the opportunity that indentured servitude promised. By the 1780s Andrew Judge lived in his own home in Fairfax County. Listed among the occupants of his home were six additional residents, one of whom was black. It’s uncertain if Andrew Judge owned a slave or if he simply hired a free black person who lived on and worked his land. What is clear from the evidence left behind is that Judge left Mount Vernon and his enslaved daughter behind. Perhaps he attempted to purchase Betty and his child but was refused the opportunity by the Washingtons. Or maybe Judge simply didn’t want a complicated relationship with an enslaved woman and a mixed-race daughter. Whatever hope, if any, Betty had placed upon the relationship with Andrew Judge collapsed quickly, leaving her at Mount Vernon to raise Ona and her siblings, including Philadelphia, a daughter she gave birth to after Ona but before Judge left, sometime around 1780.

Leaving his child behind at Mount Vernon, Andrew Judge’s parting gift to his daughter was a surname and a unique first name. The name is both African and Gaelic, and no other slave at Mount Vernon or the White House on the Pamunkey River was named Ona. Perhaps even more exceptional was that she was given a middle name, Maria. Her distinctive name set her apart from her siblings and from the majority of the other bondmen and bondwomen who toiled with her in Virginia.

The slaves who were directly connected to the work at the Mansion House lived across the road from the blacksmith’s forge in the communal space known as the Quarters, or House for Families. Betty and other women who worked in the Mansion House were typically required to be present from sunrise to sundown, preparing meals, mending clothes, cleaning, spinning, and performing other domestic tasks, leaving most enslaved children separated from their parent or parents most of the day. Many of the children at Mount Vernon began structured labor between the ages of nine and fourteen, but most performed odd jobs just as soon as they were physically able. As very young enslaved children were unhelpful and sometimes considered a nuisance, they were often left in the Quarters without much supervision beyond the older slave women, who were deemed incapable of working in the fields and no longer up to the task of domestic work.

Bushy haired, with light skin and freckles, a young Ona probably spent some of her days playing with her siblings and other enslaved children in the Quarters. More often than not, though, she had to learn how to fend for herself. Judge and the other children at Mount Vernon cried out in loneliness for their parents, witnessed the brutality of whippings and corporal punishment, and fell victim to early death due to accidental fires and drowning. Childhood for enslaved girls and boys was fleeting and fraught with calamity. Many perished before reaching young adulthood. Judge’s childhood wasn’t shortened by a plantation fatality. Instead, hers ended at age ten, when she was called to serve Martha Washington up at the Mansion House.

A good number of children at Mount Vernon did not live with both of their parents, a circumstance created by the separation of enslaved spouses. Washington may not have broken up slave marriages by selling away husbands and wives, but he was not averse to separating slave couples by placing them on different farms. While he may not have purposefully disrupted slave unions, the business of slavery and the needs of Mount Vernon always came first. For slave couples and enslaved families, this meant that they would see each other only when permission was given.

Just like other enslaved children, Ona Judge did not spend the majority of her youth with two parents. Andrew Judge had the privilege of white skin and the power anchored in a male body that allowed him to slip away from a life of unpaid labor. Betty had neither gender nor race on her side, and spent the entirety of her life in human bondage in Virginia, a colony that would eventually become the slave-breeding capital of a new nation. Ona Judge learned valuable lessons from both of her parents. From her mother she would learn the power of perseverance. From her father, Judge would learn that the decision to free oneself trumped everything, no matter who was left behind.

Recenzii

“A fascinating and moving account of a courageous and resourceful woman. Beautifully written and utilizing previously untapped sources it sheds new light both on the father of our country and on the intersections of slavery and freedom in the flawed republic he helped to found.”

"Totally engrossing and absolutely necessary for understanding the birth of the American Republic, Never Caught is richly human history from the vantage point of the enslaved fifth of the early American population. Here is Ona Judge’s (successful) quest for freedom, on one side, and, on the other, George and Martha Washington’s (vain) use of federal power to try to keep her enslaved.”

"Never Caught is the compelling story of Ona Judge Staines, the woman who successfully defied George and Martha Washington in order to live as free woman. With vivid prose and deep sympathy, Dunbar paints a portrait of woman whose life reveals the contradictions at the heart of the American founding: men like Washington fought for liberty for themselves even as they kept people like Ona Staines in bondage. There is no way to really know the Washingtons without knowing this story."

"Dunbar has teased out Ona Judge from the shadows of history and given us a determined woman who rejected life as a slave in the comfortable household of George Washington for the risks of freedom . We see Washington -- a man torn by conflicting sentiments about slavery -- in a new and ambiguous light, and plunge with Judge into the teeming cities of the young republic, where for the first time Americans are beginning to grapple with the contradiction between the Founders' ideals and the unyielding fact of slavery. No one who reads this book will think quite the same way about George and Martha Washington again."

"Dunbar brings to life the forgotten story of a woman who fled enslavement from America’s First Family. Her mostly Northern story is a powerful reminder that the tentacles of slavery could reach from the South, all the way to the state of New Hampshire. The surprising part of this true history is not that she achieved her freedom, but the lengths to which George and Martha Washington would go to try to recapture a young woman who insulted them by rejecting bondage."

“In this riveting and thoroughly researched account of the life of Ona Judge Staines, historian Erica Armstrong Dunbar carefully and compellingly constructs enslaved life inside The President's House and in the larger urban and rural communities of the time. A true page-turner, readers will come away with a deeper appreciation of enslaved people’s lives and a disturbing portrait of George and Martha Washington as slave owners. This book will change the way we study the history of slavery in the U.S, the history of American Presidents, and especially the burgeoning field of black women’s history.”

“With the production of the Tony-award winning play, Hamilton, many Americans have been reminded of the noble actions of the nation’s fathers and mothers in birthing a new country founded on democracy, liberty, and freedom. In Never Caught historian Erica Armstrong Dunbar pulls back the curtain on their individual actions by focusing on Ona Judge, an enslaved woman owned by Martha and George Washington, who stole herself to freedom and refused to be reenslaved. Piecing together the fragments of a life, in vivid prose, Dunbar reminds us of the tremendous toll slavery visited on men and women of conscience and conviction, both black and white. This is a must read for anyone interested in this nation’s long pursuit of perfecting freedom.”

"A startling, well-researched . . . narrative that seriously questions the intentions of our first president."

"A crisp and compulsively readable feat of research and storytelling."

“There are books that can take over your life: Try as you might, you can’t seem to escape their mysterious power. That’s the feeling I had when reading the tour de force, Never Caught.”

"[Dunbar] sketches an evocative portrait of [Ona's] daily life, both before and after her risky escape. For the reader, as for Judge, George Washington the Founding Father takes a back seat to George Washington the slave master.

"Dunbar weaves an unforgettable story about a courageous woman willing to risk everything for freedom."

"Erica Armstrong Dunbar combines the known facts of Ona’s life in service to the Washingtons with vivid descriptions of the physical and emotional conditions early American slaves faced."

"Compulsively readible"

“A valuable addition to African-American history, Never Caught pays a triple dividend.”

“A story of extraordinary grit.”

Never Caught is a gripping story of courage of a black slave woman who sacrificed many things including her family to gain freedom. Never Caught shows freedom is more important than anything else. What makes Never Caught uniquely interesting and important is that this is one of the rare narratives from a black woman slave. It also shines light on the dark corners of American history and the first Family, the Washingtons.

"Totally engrossing and absolutely necessary for understanding the birth of the American Republic, Never Caught is richly human history from the vantage point of the enslaved fifth of the early American population. Here is Ona Judge’s (successful) quest for freedom, on one side, and, on the other, George and Martha Washington’s (vain) use of federal power to try to keep her enslaved.”

"Never Caught is the compelling story of Ona Judge Staines, the woman who successfully defied George and Martha Washington in order to live as free woman. With vivid prose and deep sympathy, Dunbar paints a portrait of woman whose life reveals the contradictions at the heart of the American founding: men like Washington fought for liberty for themselves even as they kept people like Ona Staines in bondage. There is no way to really know the Washingtons without knowing this story."

"Dunbar has teased out Ona Judge from the shadows of history and given us a determined woman who rejected life as a slave in the comfortable household of George Washington for the risks of freedom . We see Washington -- a man torn by conflicting sentiments about slavery -- in a new and ambiguous light, and plunge with Judge into the teeming cities of the young republic, where for the first time Americans are beginning to grapple with the contradiction between the Founders' ideals and the unyielding fact of slavery. No one who reads this book will think quite the same way about George and Martha Washington again."

"Dunbar brings to life the forgotten story of a woman who fled enslavement from America’s First Family. Her mostly Northern story is a powerful reminder that the tentacles of slavery could reach from the South, all the way to the state of New Hampshire. The surprising part of this true history is not that she achieved her freedom, but the lengths to which George and Martha Washington would go to try to recapture a young woman who insulted them by rejecting bondage."

“In this riveting and thoroughly researched account of the life of Ona Judge Staines, historian Erica Armstrong Dunbar carefully and compellingly constructs enslaved life inside The President's House and in the larger urban and rural communities of the time. A true page-turner, readers will come away with a deeper appreciation of enslaved people’s lives and a disturbing portrait of George and Martha Washington as slave owners. This book will change the way we study the history of slavery in the U.S, the history of American Presidents, and especially the burgeoning field of black women’s history.”

“With the production of the Tony-award winning play, Hamilton, many Americans have been reminded of the noble actions of the nation’s fathers and mothers in birthing a new country founded on democracy, liberty, and freedom. In Never Caught historian Erica Armstrong Dunbar pulls back the curtain on their individual actions by focusing on Ona Judge, an enslaved woman owned by Martha and George Washington, who stole herself to freedom and refused to be reenslaved. Piecing together the fragments of a life, in vivid prose, Dunbar reminds us of the tremendous toll slavery visited on men and women of conscience and conviction, both black and white. This is a must read for anyone interested in this nation’s long pursuit of perfecting freedom.”

"A startling, well-researched . . . narrative that seriously questions the intentions of our first president."

"A crisp and compulsively readable feat of research and storytelling."

“There are books that can take over your life: Try as you might, you can’t seem to escape their mysterious power. That’s the feeling I had when reading the tour de force, Never Caught.”

"[Dunbar] sketches an evocative portrait of [Ona's] daily life, both before and after her risky escape. For the reader, as for Judge, George Washington the Founding Father takes a back seat to George Washington the slave master.

"Dunbar weaves an unforgettable story about a courageous woman willing to risk everything for freedom."

"Erica Armstrong Dunbar combines the known facts of Ona’s life in service to the Washingtons with vivid descriptions of the physical and emotional conditions early American slaves faced."

"Compulsively readible"

“A valuable addition to African-American history, Never Caught pays a triple dividend.”

“A story of extraordinary grit.”

Never Caught is a gripping story of courage of a black slave woman who sacrificed many things including her family to gain freedom. Never Caught shows freedom is more important than anything else. What makes Never Caught uniquely interesting and important is that this is one of the rare narratives from a black woman slave. It also shines light on the dark corners of American history and the first Family, the Washingtons.