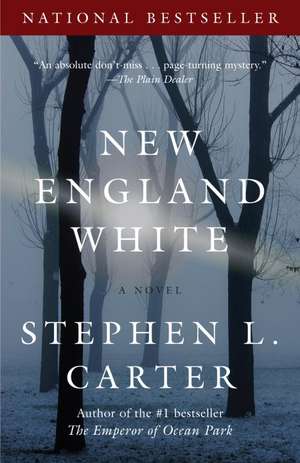

New England White

Autor Stephen L. Carteren Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2008

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Listen Up (2007)

Preț: 100.86 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 151

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.30€ • 19.94$ • 16.06£

19.30€ • 19.94$ • 16.06£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375712913

ISBN-10: 0375712917

Pagini: 617

Dimensiuni: 131 x 204 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.45 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0375712917

Pagini: 617

Dimensiuni: 131 x 204 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.45 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Stephen L. Carter is the William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Law at Yale University, where he has taught since 1982. He is the author of the best-selling novel The Emperor of Ocean Park, and seven acclaimed nonfiction books, including The Culture of Disbelief: How American Law and Politics Trivialize Religious Devotion and Civility: Manner, Morals, and the Etiquette of Democracy. He and his family live near New Haven, Connecticut.

Extras

Chapter One: Shortcut

(I)

On Friday the cat disappeared, the White House phoned, and Jeannie’s fever—said the sitter when Julia called from the echoing marble lobby of Lombard Hall, where she and her husband were fêting shadowy alumni, one or two facing indictment, whose only virtue was piles of money—hit 103. After that, things got worser faster, as her grandmother used to say, although Granny Vee’s Harlem locutions, shaped to the rhythm of an era when the race possessed a stylish sense of humor about itself, would not have gone over well in the Landing, and Julia Carlyle had long schooled herself to avoid them.

The cat was the smallest problem, even if later it turned out to be a portent. Rainbow Coalition, the children’s smelly feline mutt, had vanished before and usually came back, but now and then stayed away and was dutifully replaced by another dreadful creature of the same name. The White House was another matter. Lemaster’s college roommate, now residing in the Oval Office, telephoned at least once a month, usually to shoot the breeze, a thing it had never before occurred to Julia that Presidents of the United States did. As to Jeannie, well, the child was a solid eight years into a feverish childhood, the youngest of four, and her mother knew by now not to rush home at each spike of the thermometer. Tylenol and cool compresses had so far defeated every virus that had dared attack her child and would stymie this one, too. Julia gave the sitter her marching orders and returned to the endless dinner in time for Lemaster’s closing jokes. It was eleven minutes before ten on the second Friday in November in the year of our Lord 2003. Outside Lombard Hall, the snow had arrived early, two inches on the ground and more expected. As the police later would reconstruct the night’s events, Professor Kellen Zant was already dead and on the way to town in his car.

(II)

After. Big cushy flakes still falling. Julia and Lemaster were barreling along Four Mile Road in their Cadillac Escalade with all the extras, color regulation black, as befitted their role as the most celebrated couple in African America’s lonely Harbor County outpost. That, at least, was how Julia saw them, even after the family’s move six years ago out into what clever Lemaster called “the heart of whiteness.” For most of their marriage they had lived in Elm Harbor, largest city in the county and home of the university her husband now led. By now they should have moved back, but the drafty old mansion the school set aside for its president was undergoing renovation, a firm condition Lemaster had placed on his acceptance of the post. The trustees had worried about how it would look to spend so much on a residence at a time when funds to fix the classrooms were difficult to raise, but Lemaster, as always with his public, had been at once reasonable and adamant. “People value you more,” he had explained to his wife, “if it costs more to get you than they expected.”

“Or they hate you for it,” Julia had objected, but Lemaster stood his ground; for, within the family, he was a typical West Indian male, and therefore merely adamant.

They drove. Huge flakes swirled toward the windshield, the soft, chunky variety that signals to any New Englander that the storm is moving slowly and the eye is yet to come. Julia sulked against the dark leather, steaming with embarrassment, having called two of the alums by each other’s names, and having referred half the night to a wife named Carlotta as Charlotte, who then encouraged her, in that rich Yankee way, not to worry about it, dear, it’s a common mistake. Lemaster, who had never forgotten a name in his life, charmed everybody into smiling, but as anyone who has tried to raise money from the wealthy knows, a tiny sliver of offense can cut a potential gift by half or more, and in this crowd, half might mean eight figures.

Julia said, “Vanessa’s not setting fires any more.” Vanessa, a high-school senior, being the second of their four children. The first and the third—their two boys—were both away at school.

Her husband said, “Thank you for tonight.”

“Did you hear what I said?”

“I did, my love.” The words rapid and skeptical, rich with that teasing, not-quite-British lilt. “Did you hear what I said?” Turning lightly but swiftly to avoid a darting animal. “I know you hate these things. I promise to burden you with as few as possible.”

“Oh, Lemmie, come on. I was awful. You’ll raise more money if you leave me behind.”

“Wrong, Jules. Cameron Knowland told me he so enjoyed your company that he’s upping his pledge by five million.”

Julia in one of her moods, reassurance the last thing she craved. Clever wind whipped the snow into concentric circles of whiteness in the headlights, creating the illusion that the massive car was being drawn downward into a funnel. Four Mile Road was not the quickest route home from the city, but the Carlyles were planning a detour to the multiplex to pick up their second child, out for the first time in a while with her boyfriend, “That Casey,” as Lemaster called him. The GPS screen on the dashboard showed them well off the road, meaning the computer had never heard of Four Mile, which did not, officially, exist. But Lemaster would not forsake a beloved shortcut, even in a storm, and unmapped country lanes were his favorite.

“Cameron Knowland,” Julia said distinctly, “is a pig.” Her husband waited. “I’m glad the SEC people are after him. I hope he goes to jail.”

“It isn’t Cameron, Jules, it’s his company.” Lemaster’s favorite tone of light, donnish correction, which she had once, long ago, loved. “The most that would be imposed is a civil fine.”

“All I know is, he kept looking down my dress.”

“You should have slapped his face.” She turned in surprise, and what felt distantly like gratitude. Lemaster laughed. “Cameron would have taken his pledge back, but Carlotta would have doubled it.”

A brief marital silence, Julia painfully aware that tonight she had entirely misplaced the delicate, not-quite-flirty insouciance that had made her, a quarter-century ago, the most popular girl at her New Hampshire high school. Like her husband, she was of something less than average height. Her skin was many shades lighter than his blue-black, for her unknown father had been, as Lemaster insisted on calling him, a Caucasian. Her gray eyes were strangely large for a woman of her diminutive stature. Her slightly jutting jaw was softened by an endearing dimple. Her lips were alluringly crooked. When she smiled, the left side of her wide mouth rose a little farther than the right, a signal, her husband liked to say, of her quietly liberal politics. She was by reputation an easy person to like. But there were days when it all felt false, and forced. Being around the campus did that to her. She had been a deputy dean of the divinity school for almost three years before Lemaster was brought back from Washington to run the university, and her husband’s ascension had somehow increased her sense of not belonging. Julia and the children had remained in the Landing during her husband’s year and a half as White House counsel. Lemaster had spent as many weekends as he could at home. People invented delicious rumors to explain his absence, none of them true, but as Granny Vee used to say, the truth only matters if you want it to.

“You’re so silly,” she said, although, to her frequent distress, her husband was anything but. She looked out the window. Slickly whitened trees slipped past, mostly conifers. It was early for snow, not yet winter, not yet anything, really: that long season of pre-Thanksgiving New England chill when the stores declared it Christmas season but everybody else only knew it was cold. Julia had spent most of her childhood in Hanover, New Hampshire, where her mother had been a professor at Dartmouth, and she was accustomed to early snow, but this was ridiculous. She said, “Can we talk about Vanessa?”

“What about her?”

“The fires. It’s all over with, Lemmie.”

A pause. Lemaster played with the satellite radio, switching, without asking, from her adored Broadway show tunes—Granny Vee had loved them, so she did, too—to his own secret passion, the more rebellious and edgy and less commercial end of the hip-hop spectrum. The screen informed her in glowing green letters that the furious sexual bombast now assaulting her eardrums from nine speakers was something called Goodie Mobb. “How do you know it’s over?” he asked.

“Well, for one thing, she hasn’t done it in a year. For another, Dr. Brady says so.”

“Nine months,” said Lemaster, precisely. “And she’s not Vincent Brady’s daughter,” he added, slender fingers tightening ever so slightly on the wheel, but in caution, not anger, for the weather had slipped from abhorrent to atrocious. She glanced his way, turning down the throbbing music just in case, for a change, he wanted to talk, but he was craning forward, hoping for a better view, heavy flakes now falling faster than the wipers could clean. He wore glasses with steel rims. His goatee and mustache were so perfectly trimmed they might have been invisible against his smooth ebon flesh, except for the thousand flecks of gray that reshaped to follow the motion of his jaw whenever he spoke. “What a mistake,” said Lemaster, but it took Julia a second to work out that he was referring to the psychiatrist, and not one among the many enemies he had effortlessly, and surprisingly, collected during his six months as head of the university.

Julia had been stunned when the judge ordered the choice of intensive therapy or a jail sentence. Vanessa cheerily offered to do the time— “You can’t say I haven’t earned it”—but Julia, who used to volunteer at the juvenile detention facility in the city, knew what it was like. She could not imagine her vague, brainy, artistic daughter surviving two days among the hard-shelled teens scooped off the street corners and dumped there. As her grandmother used to say, there are our black people and there are other black people—and all her life Julia had secretly believed it. So Lemaster had chosen Brady, a professor at the medical school who was supposed to be one of the best adolescent psychiatrists in the country, and Julia, who, like Vanessa, would have preferred a woman, or at least someone from within the darker nation, held her peace. She had never imagined, twenty years ago, growing into the sort of wife who would.

She had never imagined a lot of things.

“Cameron told me something interesting,” said Lemaster when he decided she had stewed long enough. They passed two gray horses in a paddock, wearing blankets against the weather but not otherwise concerned, watching the sparse nighttime traffic with their shining eyes. “He had the strangest call a couple of weeks ago.” That confident, can-do laugh, a hand lifted from the wheel in emphasis, a gleeful glance in Julia’s direction. Lemaster loved being one up on anyone in the vicinity, and made no exception for his own wife. “From an old friend of yours, as a matter of fact. Apparently—”

“Lemmie, look out! Look out!”

Too late.

(III)

Every New Englander knows that nighttime snowy woods are noisy. Chittering, sneaking animals, whistling, teasing wind, cracking, creaking branches—there is plenty to hear, except when your Escalade is in a ditch, the engine hissing and missing, hissing and missing, and Goodie Mobb still yallowing from nine speakers. Julia pried herself from behind the air bag, her husband’s outstretched hand ready to help. Shivering, she looked up and down the indentation in the snow that marked Four Mile Road. Lemaster had his hands on her face. Confused, she slapped them away. He patiently turned her back to look at him. She realized that he was asking if she was all right. There was blood on his forehead and in his mouth, a lot of it. Her turn to ask how he was doing, and his turn to reassure her.

No cell-phone service out here: they both tried.

“What do we do now?” said Julia, shivering for any number of good reasons. She tried to decide whether to be angry at him for taking his eyes off the road just before a sharp bend that had not budged in their six years of living out here.

“We wait for the next car to come by.”

“Nobody drives this way but you.”

Lemaster was out of the ditch, up on the road. “We drove ten minutes and passed two cars. Another one will be along in a bit.” He paused and, for a wretched moment, she feared he might be calculating the precise moment when the next was expected. “We’ll leave the headlights on. The next car will see us and slow down.” His voice was calm, as calm as the day the President asked him to come down to Washington and, as a pillar of integrity, clean up the latest mess in the White House; as calm as the night two decades ago when Julia told him she was pregnant and he answered without excitement or reproach that they must marry. Moral life, Lemaster often said, required reason more than passion. Maybe so, but too much reason could drive you nuts. “You should wait in the car. It’s cold out here.”

“What about Vanessa? She’s waiting for us to pick her up.”

“She’ll wait.”

Julia, uncertain, did as her husband suggested. He was eight years her senior, a difference that had once provided her a certain assurance but in recent years had left her feeling more and more that he treated her like a child. Granny Vee used to say that if you married a man because you wanted him to take care of you, you ran the risk that he would. About to climb into the warmth of the car, she spotted by moonlight a ragged bundle in the ditch a few yards away. She took half a step toward it, and a pair of feral creatures with glowing eyes jerked furry heads up from their meal and scurried into the trees. A deer, she decided, the dark mound mostly covered with snow, probably struck by a car and thrown into the ditch, transformed into dinner for whatever animals refused to hibernate. Shivering, she buttoned her coat, then turned back toward the Escalade. She did not need a close look at some bloodstained animal with the most succulent pieces missing. Only once she had her hand on the door handle did she stop.

Deer, she reminded herself, rarely wear shoes.

From the Hardcover edition.

(I)

On Friday the cat disappeared, the White House phoned, and Jeannie’s fever—said the sitter when Julia called from the echoing marble lobby of Lombard Hall, where she and her husband were fêting shadowy alumni, one or two facing indictment, whose only virtue was piles of money—hit 103. After that, things got worser faster, as her grandmother used to say, although Granny Vee’s Harlem locutions, shaped to the rhythm of an era when the race possessed a stylish sense of humor about itself, would not have gone over well in the Landing, and Julia Carlyle had long schooled herself to avoid them.

The cat was the smallest problem, even if later it turned out to be a portent. Rainbow Coalition, the children’s smelly feline mutt, had vanished before and usually came back, but now and then stayed away and was dutifully replaced by another dreadful creature of the same name. The White House was another matter. Lemaster’s college roommate, now residing in the Oval Office, telephoned at least once a month, usually to shoot the breeze, a thing it had never before occurred to Julia that Presidents of the United States did. As to Jeannie, well, the child was a solid eight years into a feverish childhood, the youngest of four, and her mother knew by now not to rush home at each spike of the thermometer. Tylenol and cool compresses had so far defeated every virus that had dared attack her child and would stymie this one, too. Julia gave the sitter her marching orders and returned to the endless dinner in time for Lemaster’s closing jokes. It was eleven minutes before ten on the second Friday in November in the year of our Lord 2003. Outside Lombard Hall, the snow had arrived early, two inches on the ground and more expected. As the police later would reconstruct the night’s events, Professor Kellen Zant was already dead and on the way to town in his car.

(II)

After. Big cushy flakes still falling. Julia and Lemaster were barreling along Four Mile Road in their Cadillac Escalade with all the extras, color regulation black, as befitted their role as the most celebrated couple in African America’s lonely Harbor County outpost. That, at least, was how Julia saw them, even after the family’s move six years ago out into what clever Lemaster called “the heart of whiteness.” For most of their marriage they had lived in Elm Harbor, largest city in the county and home of the university her husband now led. By now they should have moved back, but the drafty old mansion the school set aside for its president was undergoing renovation, a firm condition Lemaster had placed on his acceptance of the post. The trustees had worried about how it would look to spend so much on a residence at a time when funds to fix the classrooms were difficult to raise, but Lemaster, as always with his public, had been at once reasonable and adamant. “People value you more,” he had explained to his wife, “if it costs more to get you than they expected.”

“Or they hate you for it,” Julia had objected, but Lemaster stood his ground; for, within the family, he was a typical West Indian male, and therefore merely adamant.

They drove. Huge flakes swirled toward the windshield, the soft, chunky variety that signals to any New Englander that the storm is moving slowly and the eye is yet to come. Julia sulked against the dark leather, steaming with embarrassment, having called two of the alums by each other’s names, and having referred half the night to a wife named Carlotta as Charlotte, who then encouraged her, in that rich Yankee way, not to worry about it, dear, it’s a common mistake. Lemaster, who had never forgotten a name in his life, charmed everybody into smiling, but as anyone who has tried to raise money from the wealthy knows, a tiny sliver of offense can cut a potential gift by half or more, and in this crowd, half might mean eight figures.

Julia said, “Vanessa’s not setting fires any more.” Vanessa, a high-school senior, being the second of their four children. The first and the third—their two boys—were both away at school.

Her husband said, “Thank you for tonight.”

“Did you hear what I said?”

“I did, my love.” The words rapid and skeptical, rich with that teasing, not-quite-British lilt. “Did you hear what I said?” Turning lightly but swiftly to avoid a darting animal. “I know you hate these things. I promise to burden you with as few as possible.”

“Oh, Lemmie, come on. I was awful. You’ll raise more money if you leave me behind.”

“Wrong, Jules. Cameron Knowland told me he so enjoyed your company that he’s upping his pledge by five million.”

Julia in one of her moods, reassurance the last thing she craved. Clever wind whipped the snow into concentric circles of whiteness in the headlights, creating the illusion that the massive car was being drawn downward into a funnel. Four Mile Road was not the quickest route home from the city, but the Carlyles were planning a detour to the multiplex to pick up their second child, out for the first time in a while with her boyfriend, “That Casey,” as Lemaster called him. The GPS screen on the dashboard showed them well off the road, meaning the computer had never heard of Four Mile, which did not, officially, exist. But Lemaster would not forsake a beloved shortcut, even in a storm, and unmapped country lanes were his favorite.

“Cameron Knowland,” Julia said distinctly, “is a pig.” Her husband waited. “I’m glad the SEC people are after him. I hope he goes to jail.”

“It isn’t Cameron, Jules, it’s his company.” Lemaster’s favorite tone of light, donnish correction, which she had once, long ago, loved. “The most that would be imposed is a civil fine.”

“All I know is, he kept looking down my dress.”

“You should have slapped his face.” She turned in surprise, and what felt distantly like gratitude. Lemaster laughed. “Cameron would have taken his pledge back, but Carlotta would have doubled it.”

A brief marital silence, Julia painfully aware that tonight she had entirely misplaced the delicate, not-quite-flirty insouciance that had made her, a quarter-century ago, the most popular girl at her New Hampshire high school. Like her husband, she was of something less than average height. Her skin was many shades lighter than his blue-black, for her unknown father had been, as Lemaster insisted on calling him, a Caucasian. Her gray eyes were strangely large for a woman of her diminutive stature. Her slightly jutting jaw was softened by an endearing dimple. Her lips were alluringly crooked. When she smiled, the left side of her wide mouth rose a little farther than the right, a signal, her husband liked to say, of her quietly liberal politics. She was by reputation an easy person to like. But there were days when it all felt false, and forced. Being around the campus did that to her. She had been a deputy dean of the divinity school for almost three years before Lemaster was brought back from Washington to run the university, and her husband’s ascension had somehow increased her sense of not belonging. Julia and the children had remained in the Landing during her husband’s year and a half as White House counsel. Lemaster had spent as many weekends as he could at home. People invented delicious rumors to explain his absence, none of them true, but as Granny Vee used to say, the truth only matters if you want it to.

“You’re so silly,” she said, although, to her frequent distress, her husband was anything but. She looked out the window. Slickly whitened trees slipped past, mostly conifers. It was early for snow, not yet winter, not yet anything, really: that long season of pre-Thanksgiving New England chill when the stores declared it Christmas season but everybody else only knew it was cold. Julia had spent most of her childhood in Hanover, New Hampshire, where her mother had been a professor at Dartmouth, and she was accustomed to early snow, but this was ridiculous. She said, “Can we talk about Vanessa?”

“What about her?”

“The fires. It’s all over with, Lemmie.”

A pause. Lemaster played with the satellite radio, switching, without asking, from her adored Broadway show tunes—Granny Vee had loved them, so she did, too—to his own secret passion, the more rebellious and edgy and less commercial end of the hip-hop spectrum. The screen informed her in glowing green letters that the furious sexual bombast now assaulting her eardrums from nine speakers was something called Goodie Mobb. “How do you know it’s over?” he asked.

“Well, for one thing, she hasn’t done it in a year. For another, Dr. Brady says so.”

“Nine months,” said Lemaster, precisely. “And she’s not Vincent Brady’s daughter,” he added, slender fingers tightening ever so slightly on the wheel, but in caution, not anger, for the weather had slipped from abhorrent to atrocious. She glanced his way, turning down the throbbing music just in case, for a change, he wanted to talk, but he was craning forward, hoping for a better view, heavy flakes now falling faster than the wipers could clean. He wore glasses with steel rims. His goatee and mustache were so perfectly trimmed they might have been invisible against his smooth ebon flesh, except for the thousand flecks of gray that reshaped to follow the motion of his jaw whenever he spoke. “What a mistake,” said Lemaster, but it took Julia a second to work out that he was referring to the psychiatrist, and not one among the many enemies he had effortlessly, and surprisingly, collected during his six months as head of the university.

Julia had been stunned when the judge ordered the choice of intensive therapy or a jail sentence. Vanessa cheerily offered to do the time— “You can’t say I haven’t earned it”—but Julia, who used to volunteer at the juvenile detention facility in the city, knew what it was like. She could not imagine her vague, brainy, artistic daughter surviving two days among the hard-shelled teens scooped off the street corners and dumped there. As her grandmother used to say, there are our black people and there are other black people—and all her life Julia had secretly believed it. So Lemaster had chosen Brady, a professor at the medical school who was supposed to be one of the best adolescent psychiatrists in the country, and Julia, who, like Vanessa, would have preferred a woman, or at least someone from within the darker nation, held her peace. She had never imagined, twenty years ago, growing into the sort of wife who would.

She had never imagined a lot of things.

“Cameron told me something interesting,” said Lemaster when he decided she had stewed long enough. They passed two gray horses in a paddock, wearing blankets against the weather but not otherwise concerned, watching the sparse nighttime traffic with their shining eyes. “He had the strangest call a couple of weeks ago.” That confident, can-do laugh, a hand lifted from the wheel in emphasis, a gleeful glance in Julia’s direction. Lemaster loved being one up on anyone in the vicinity, and made no exception for his own wife. “From an old friend of yours, as a matter of fact. Apparently—”

“Lemmie, look out! Look out!”

Too late.

(III)

Every New Englander knows that nighttime snowy woods are noisy. Chittering, sneaking animals, whistling, teasing wind, cracking, creaking branches—there is plenty to hear, except when your Escalade is in a ditch, the engine hissing and missing, hissing and missing, and Goodie Mobb still yallowing from nine speakers. Julia pried herself from behind the air bag, her husband’s outstretched hand ready to help. Shivering, she looked up and down the indentation in the snow that marked Four Mile Road. Lemaster had his hands on her face. Confused, she slapped them away. He patiently turned her back to look at him. She realized that he was asking if she was all right. There was blood on his forehead and in his mouth, a lot of it. Her turn to ask how he was doing, and his turn to reassure her.

No cell-phone service out here: they both tried.

“What do we do now?” said Julia, shivering for any number of good reasons. She tried to decide whether to be angry at him for taking his eyes off the road just before a sharp bend that had not budged in their six years of living out here.

“We wait for the next car to come by.”

“Nobody drives this way but you.”

Lemaster was out of the ditch, up on the road. “We drove ten minutes and passed two cars. Another one will be along in a bit.” He paused and, for a wretched moment, she feared he might be calculating the precise moment when the next was expected. “We’ll leave the headlights on. The next car will see us and slow down.” His voice was calm, as calm as the day the President asked him to come down to Washington and, as a pillar of integrity, clean up the latest mess in the White House; as calm as the night two decades ago when Julia told him she was pregnant and he answered without excitement or reproach that they must marry. Moral life, Lemaster often said, required reason more than passion. Maybe so, but too much reason could drive you nuts. “You should wait in the car. It’s cold out here.”

“What about Vanessa? She’s waiting for us to pick her up.”

“She’ll wait.”

Julia, uncertain, did as her husband suggested. He was eight years her senior, a difference that had once provided her a certain assurance but in recent years had left her feeling more and more that he treated her like a child. Granny Vee used to say that if you married a man because you wanted him to take care of you, you ran the risk that he would. About to climb into the warmth of the car, she spotted by moonlight a ragged bundle in the ditch a few yards away. She took half a step toward it, and a pair of feral creatures with glowing eyes jerked furry heads up from their meal and scurried into the trees. A deer, she decided, the dark mound mostly covered with snow, probably struck by a car and thrown into the ditch, transformed into dinner for whatever animals refused to hibernate. Shivering, she buttoned her coat, then turned back toward the Escalade. She did not need a close look at some bloodstained animal with the most succulent pieces missing. Only once she had her hand on the door handle did she stop.

Deer, she reminded herself, rarely wear shoes.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“An absolute don't-miss . . . page-turning mystery.” —The Plain Dealer“Earthshaking. . . . Keeps us guessing . . . right up to the intricately deployed end.” —The New York Times Book Review“Carter twists the plotlines like pretzels while wryly skewering America's wealthy intellectual elite.” —People“A testament to [Carter's] formidable storytelling. The novel's satisfying conclusion also points out how irrelevant genre labels have become.” —The Washington Post

Descriere

Two lesser characters from Carter's bestselling first novel, "The Emperor of Ocean Park"--husband and wife Lemaster and Julia Carlyle--take center stage in this compelling, literate page-turner that blends a gripping whodunit with complex discussions of politics and race in contemporary America.

Premii

- Listen Up Editor's Choice, 2007