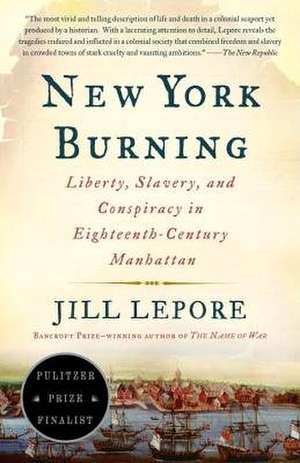

New York Burning: Liberty, Slavery, and Conspiracy in Eighteenth-Century Manhattan

Autor Jill Leporeen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2006

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

ALA Notable Books (2006)

Anisfield-Wolf Award Winner

Over a frigid few weeks in the winter of 1741, ten fires blazed across Manhattan. With each new fire, panicked whites saw more evidence of a slave uprising. In the end, thirteen black men were burned at the stake, seventeen were hanged and more than one hundred black men and women were thrown into a dungeon beneath City Hall.

In New York Burning, Bancroft Prize-winning historian Jill Lepore recounts these dramatic events, re-creating, with path-breaking research, the nascent New York of the seventeenth century. Even then, the city was a rich mosaic of cultures, communities and colors, with slaves making up a full one-fifth of the population. Exploring the political and social climate of the times, Lepore dramatically shows how, in a city rife with state intrigue and terror, the threat of black rebellion united the white political pluralities in a frenzy of racial fear and violence.

Preț: 155.59 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 233

Preț estimativ în valută:

29.80€ • 30.70$ • 24.96£

29.80€ • 30.70$ • 24.96£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400032266

ISBN-10: 1400032261

Pagini: 323

Ilustrații: 17 ILLUS IN TEXT; 1 MAP

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 1400032261

Pagini: 323

Ilustrații: 17 ILLUS IN TEXT; 1 MAP

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Jill Lepore is Professor of History at Harvard University and the author of The Name of War: King Philip's War and the Origins of American Identity, which won both the Bancroft Prize and Phi Beta Kappa's Ralph Waldo Emerson Award, as well as A is for American: Letters and Other Characters in the Newly United States. She is a contributor to The New Yorker. Lepore lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Extras

Ice

After ten feet of snow over Christmas, the skies cleared in January. In the brightening sun, poor widows and orphaned children hobbled through the snow to a house on Smith Street, across from the Black Horse Tavern, where a charity promised "To Feed the hungry & Cloath the naked," or at least those "in Real Need of Relief." But in February, the fierce weather returned. "We have now here a second Winter more Severe than it was some Weeks past," Zenger's Weekly Journal reported on February 2, the feast of Candlemas. "The Navigation of our River is again stopp'd by the Ice, and the poor in great want of Wood." At Peter DeLancey's farm outside the city, his "Spanish Negro" Antonio de St. Bendito, whose "Feet were frozen after the first great Snow," was still unable to walk. In the city, coals were passed out to the poor to help heat their humble homes. At John Hughson's tavern, his Irish servant girl, Mary Burton, dressed herself "in Man's Cloaths, put on Boots, and went with him in his Sleigh in the deep Snows of the Commons, to help him fetch Firewood for his Family." At David Machado's house, in the East Ward, his black slave Diana, driven to desperation by the ferocity of the cold and by the hopelessness of bondage, "took her own young Child from her Breast, and laid it in the Cold, that it froze to Death."

The first week of February, New Yorkers stared helplessly from piers along the East River as a boat was "taken by a large Cake of Ice in our Harbour, and carried by it through the Narrows, and out of sight." Watchers wondered, but could not discover, what happened to the people on board. Six more ships lay frozen in Long Island Sound, and another, sails set, crashed against the ice, abandoned. Meanwhile, from Charleston, South Carolina, came the shocking news that slaves had nearly destroyed that city, burning three hundred houses to the ground. But this turned out to have been only a rumor. On February 9, Zenger printed a quiet retraction: "The report of the Negroes rising was groundless."

Even while the weather worsened, there were still city pleasures to be had. "on Thursday, Feb. the 12th at the new Theatre in the Broad Way will be presented a Comedy call'd the Beaux Stratagem," announced a back-page ad in the New-York Weekly Journal, in the hard winter of 1741. Tickets for a box: 5 shillings; for the pit: 2 shillings and 6 pence.

For those who ventured out by the light of lanterns to attend the New York debut of George Farquhar's late Restoration comedy, it was a cold walk down "the Broad Way," a wide, straight street, paved with cobbles, slick with snow, and thickly canopied with the overburdened, icy branches of the beech and locust trees that lined it. The theatre lay just across from the Bowling Green, a triangle of land at the wide base of Broadway fenced in in 1734 "for the Beauty & Ornament of the Said Street as well as for the Recreation & delight of the Inhabitants."

An evening at the theatre must have been delightful distraction for those who could scare up the shillings, and whose boots were warm enough to keep frostbite at bay. The Beaux' Stratagem, first staged in London in 1707, was not only George Farquhar's best play but also the most successful comedy of the age. From its debut to the close of the eighteenth century, it was performed in London during every season but one; and in the 1730s alone, it was staged over a hundred times.

The appeal of The Beaux' Stratagem to eighteenth-century audiences lay chiefly in its dizzying reversal of roles and fortunes. The play tells the tale of "two gentlemen of broken fortunes," Aimwell and Archer, on a trip to the town of Lichfield. Having spent their small inheritances on the pleasures of London, the two friends travel from town to town, each taking a turn at pretending to be his companion's servant in order to help his "master" impress and seduce gullible country women. In Lichfield, the ruse works well until Aimwell falls in love with Dorinda, the wealthy daughter of Lady Bountiful, and Archer is taken with Dorinda's married sister-in-law, Mrs. Sullen. Intrigues abound, as Aimwell decides to pass himself off as his elder brother, a viscount, in hopes of securing Dorinda's hand, while a host of still sillier characters-a dishonest innkeeper, Bonniface, and his clever daughter, Cherry; Lady Bountiful's dim-witted son, Squire Sullen; Sullen's dunderheaded servant, Scrub; an amorous French count; a nefarious French priest; and a gang of particularly feckless robbers-pursue their own schemes, stage their own impostures, and plot their own plots, their beaux' stratagem, leading Archer to conclude at the end of Act II, "We're like to have as many adventures in our inn as Don Quixote had in his."

At the New Theatre on Broadway, New York's gentry-merchants, bureaucrats, lawyers, and naval officers-paid for the box seats. Everyone else-servants, artisans, sailors, soldiers, and a handful of free blacks-sat in the pit. Joe, the slave of dancing master Henry Holt, probably worked backstage. James Alexander, a Freemason, may have walked down the aisle in procession with his brother lodge members, to sit together in a row, as Masons liked to do. Attorney Joseph Murray, an avid collector of English drama who happened to live more or less across the street from the theatre, must surely have attended with his wife, Grace, daughter of the former governor, their clothes for the evening laid out, perhaps, by their housekeeper, Mrs. Dimmock; their handsome house's front steps swept clean of flurrying snow by one of the Murrays' slaves: Jack, Congo, Dido, Adam, or Caesar. Perhaps Cuba, one of attorney John Chambers's slaves, entered the theatre quietly, before the curtain rose, to place a warming pan beneath the skirt of her mistress, Chambers's wife, Anna.

The playhouse on Broadway had much to offer in the way of conviviality, but the production on the night of the twelfth was not particularly polished; eighteenth-century New York, like the rest of the colonies, was a theatrical backwater. A 1709 decree by the Governor's Council had forbidden "play acting and prize-fighting," and the city's first recorded production did not take place until 1732, when another of Farquhar's comedies, The Recruiting Officer, was performed, with "the Part of Worthy acted by the ingenious Mr. Thomas Hearly," the mayor's barber and periwig maker. Nearly a decade later, the hairdressing thespian was no longer available. In 1741, for the New York debut of The Beaux' Stratagem, the part of Aimwell was "perform'd by a Person who never appear'd on any Stage before."

Still, the crowd, coming in from the cold, must have relished Farquhar's comedy, at once a pretzel of plot twists, a farce of love and deceit (and of the deceitfulness of lovers), a slightly bawdy parody of eighteenth-century courtship, and a rather bold critique of marriage. In Act IV, after having been wooed by Aimwell and Archer, Dorinda and Mrs. Sullen compare their suitors:

Dor: . . . my lover was upon his knees to me.

Mrs. Sul: And mine was upon his tiptoes to me.

Dor: Mine vowed to die for me.

Mrs. Sul: Mine swore to die with me.

Dor: Mine spoke the softest moving things.

Mrs. Sul: Mine had his moving things too.

Dor: Mine kissed my hand ten thousand times.

Mrs. Sul: Mine has all that pleasure to come.

Dor: Mine offered marriage.

Mrs. Sul: O Lard! d'ye call that a moving thing?

If Daniel Horsmanden attended the New Theatre on the night of February 12, he would have seen much that was familiar, uncomfortably familiar, in Aimwell and Archer, two men on the make, willing to say anything and to pass themselves off as wealthier than they were, plotting to marry rich women. Horsmanden was born in England in 1694, the eldest son of the rector of All Saints Church, in Purleigh, Essex. As a young man, he declined to inherit his father's position and determined instead on a legal career. In his twenties, while studying law in London, Horsmanden pursued his own beaux' stratagem on a trip to the fashionable resort town of Tunbridge Wells with his cousin, the Virginian William Byrd II, a widower in his forties who was desperately seeking a marriage alliance that might rescue him from debt. In Tunbridge Wells, Horsmanden courted "Miss B-n-y." Byrd, having recently failed to win the hand of Miss Mary Smith (in spite of boasting of his Virginia estate of 43,000 acres and 220 slaves), scouted about for another suitable wife while composing

Tunbrigalia, a book of poems celebrating the charms of several pretty Englishwomen of his close acquaintance, including Horsmanden's older sisters, Susanna (or "Suky") and Ursula (delightfully known as "Nutty Horsmanden"):

Thrice happy Wells! where Beauty's in such store,

When could'st thou boast an Horsmanden, a Hoar,

A Borrel, Lyndsey, Searle, and Thousands more?

William Byrd fancied himself a wit: after he and Horsmanden returned to London, Byrd wrote a love letter for his tongue-tied cousin Daniel. When Horsmanden told Byrd he "was going to Tunbridge again to endeavor to get Miss B-n-y," Byrd "lent him thirty guineas for his expedition." But Byrd's pen and pocketbook failed to win Horsmanden his suit. The mysterious Miss B-n-y turned him down.

In the 1710s, Horsmanden and Byrd dined together, drank together, attended the theatre together, and spent endless hours gossiping in London taverns and coffeehouses. And they went whoring together, as is made abundantly clear in Byrd's secret diary (written in an obscure shorthand and kept under lock and key), in entries like the one from June 26, 1718: "After dinner I put some things in order and then took a nap till 5 o'clock, when Daniel Horsmanden came and we went to the park, where we had appointed to meet some ladies but they failed. Then we went to Spring Gardens where we picked up two women and carried them into the arbor and ate some cold veal and about 10 o'clock we carried them to the bagnio, where we bathed and lay with them all night and I rogered mine twice and slept pretty well, but neglected my prayers."

William Byrd neglected his prayers more than once; he was a shattered man, compulsively rogering whores. During these painful, dissolute years of Byrd's life, young Daniel Horsmanden was his boon companion. By the diary's end, it's difficult not to raise an eyebrow at the homonym in Tunbrigalia, "When could'st thou boast an Horsmanden, a Hoar . . . ?"

Byrd, for all his sexual bravado, was mortified by his dependence on cheap prostitutes. He once wrote of himself, "The struggle between the Senate and the Plebeans in the Roman Commonwealth, or betweext the King and the Parliament in England, was never half so violent as the Civil war between this Hero's Principles and his Inclinations." Visiting prostitutes gave Byrd nightmares. In September 1719 he confided in his diary, "Daniel Horsmanden came again and we went to visit a whore but she was from home. . . . I dreamed I caused a coffin to be made for me to bury myself in but I changed my mind." What gave Byrd nightmares made Horsmanden sick. Six weeks after his first visit to a prostitute, the young law student was confined to his lodgings with "a sore leg." After another episode, he "had a swelled face." The "leg" might have been a euphemism: Horsmanden may have contracted syphilis, whose symptoms during the first two years after exposure include joint pain and markedly swollen glands-the "swelled face." In any event, Horsmanden's own rather tortured relationship with prostitutes, whom he tried in vain to give up, might explain why he didn't marry until 1747, at the age of fifty-three, and never fathered any children.

In 1720, the year after William Byrd left England for Virginia, Horsmanden lost his fortune, what little was left of his inheritance, in the South Sea Bubble. It was an awful blow. He continued to study at the Inns of Court but failed to earn much of a living or to recover his considerable South Sea losses by practicing law. He was broke. Eventually, as Horsmanden later explained, "I was Oblig'd to leave England."

In 1729, Horsmanden bought a book entitled A New Survey of the Globe, by Thomas Templeman. Templeman, true to an Englishman's sense of geography, reported only two kinds of information in his curious book: the size of landmasses and the distance of every important city in the world from London. Horsmanden, penniless and aimless, made his own survey of the globe, attempting to determine in what direction to head. He studied Templeman's figures closely. Finally, he decided to sail for Virginia, where his cousin William Byrd was a member of the Governor's Council.

But Horsmanden failed in Virginia, too. He was unable to gain admission to the bar, and he left after less than two years. By 1731, Daniel Horsmanden was on his way to New York City. Miles from London: 3,471.

"Have I been traversing the Ocean for so many weeks, to be sett down again in the country I quitted?" wondered another Englishman when he arrived in New York. "This cannot be a new town, in a new world, for such must be attended with many new objects, new faces, new manners, new customs, but here I can find nothing different from what I have quitted." More than three thousand miles from London, New York struck English visitors as uncannily familiar. "The dress and external appearance of the people is the same. The houses are in the stile we are accustomed to; within doors the furniture is all English or made after English fashions. The mode of living is the same." One visitor was flustered: "Where then shall I find any difference?" He found only one: "the greater number of the Blacks."

There was, of course, another difference. Compared to London, New York was no city at all. It was only a mile long and half a mile wide. In population, New York in 1741 was second only to Boston among colonial cities (and neck and neck with Philadelphia), but against London it was a hamlet. By Thomas Templeman's reckoning, "London contains about 105,000 Houses, 840,000 Souls." In 1741, New York boasted more like 1,500 houses and 10,000 souls. But nearly 2,000 were the souls of black folk, and their numbers almost always grabbed travelers' attention. (There were probably only about 15,000 blacks in eighteenth-century London, less than 2 percent of the population, compared to New York's 20 percent.)

Despite how almost entirely English the city may have at first appeared, New York was a jumble of cultures, languages, and religions. By 1731, it even had its own synagogue, the first in Britain's colonies. Peopled with Dutch, English, Welsh, Irish, Scots, and German settlers, French Huguenots, Portuguese Jews, and African slaves and "Spanish Negroes," New York was a frenzied, factious place. "The inhabitants of New York," a visiting English vicar observed, were more than half of them Dutch and therefore "habitually frugal, industrious, and parsimonious," but the rest were of so many "different nations, different languages, and different religions, it is almost impossible to give them any precise or determinate character."

From the Hardcover edition.

After ten feet of snow over Christmas, the skies cleared in January. In the brightening sun, poor widows and orphaned children hobbled through the snow to a house on Smith Street, across from the Black Horse Tavern, where a charity promised "To Feed the hungry & Cloath the naked," or at least those "in Real Need of Relief." But in February, the fierce weather returned. "We have now here a second Winter more Severe than it was some Weeks past," Zenger's Weekly Journal reported on February 2, the feast of Candlemas. "The Navigation of our River is again stopp'd by the Ice, and the poor in great want of Wood." At Peter DeLancey's farm outside the city, his "Spanish Negro" Antonio de St. Bendito, whose "Feet were frozen after the first great Snow," was still unable to walk. In the city, coals were passed out to the poor to help heat their humble homes. At John Hughson's tavern, his Irish servant girl, Mary Burton, dressed herself "in Man's Cloaths, put on Boots, and went with him in his Sleigh in the deep Snows of the Commons, to help him fetch Firewood for his Family." At David Machado's house, in the East Ward, his black slave Diana, driven to desperation by the ferocity of the cold and by the hopelessness of bondage, "took her own young Child from her Breast, and laid it in the Cold, that it froze to Death."

The first week of February, New Yorkers stared helplessly from piers along the East River as a boat was "taken by a large Cake of Ice in our Harbour, and carried by it through the Narrows, and out of sight." Watchers wondered, but could not discover, what happened to the people on board. Six more ships lay frozen in Long Island Sound, and another, sails set, crashed against the ice, abandoned. Meanwhile, from Charleston, South Carolina, came the shocking news that slaves had nearly destroyed that city, burning three hundred houses to the ground. But this turned out to have been only a rumor. On February 9, Zenger printed a quiet retraction: "The report of the Negroes rising was groundless."

Even while the weather worsened, there were still city pleasures to be had. "on Thursday, Feb. the 12th at the new Theatre in the Broad Way will be presented a Comedy call'd the Beaux Stratagem," announced a back-page ad in the New-York Weekly Journal, in the hard winter of 1741. Tickets for a box: 5 shillings; for the pit: 2 shillings and 6 pence.

For those who ventured out by the light of lanterns to attend the New York debut of George Farquhar's late Restoration comedy, it was a cold walk down "the Broad Way," a wide, straight street, paved with cobbles, slick with snow, and thickly canopied with the overburdened, icy branches of the beech and locust trees that lined it. The theatre lay just across from the Bowling Green, a triangle of land at the wide base of Broadway fenced in in 1734 "for the Beauty & Ornament of the Said Street as well as for the Recreation & delight of the Inhabitants."

An evening at the theatre must have been delightful distraction for those who could scare up the shillings, and whose boots were warm enough to keep frostbite at bay. The Beaux' Stratagem, first staged in London in 1707, was not only George Farquhar's best play but also the most successful comedy of the age. From its debut to the close of the eighteenth century, it was performed in London during every season but one; and in the 1730s alone, it was staged over a hundred times.

The appeal of The Beaux' Stratagem to eighteenth-century audiences lay chiefly in its dizzying reversal of roles and fortunes. The play tells the tale of "two gentlemen of broken fortunes," Aimwell and Archer, on a trip to the town of Lichfield. Having spent their small inheritances on the pleasures of London, the two friends travel from town to town, each taking a turn at pretending to be his companion's servant in order to help his "master" impress and seduce gullible country women. In Lichfield, the ruse works well until Aimwell falls in love with Dorinda, the wealthy daughter of Lady Bountiful, and Archer is taken with Dorinda's married sister-in-law, Mrs. Sullen. Intrigues abound, as Aimwell decides to pass himself off as his elder brother, a viscount, in hopes of securing Dorinda's hand, while a host of still sillier characters-a dishonest innkeeper, Bonniface, and his clever daughter, Cherry; Lady Bountiful's dim-witted son, Squire Sullen; Sullen's dunderheaded servant, Scrub; an amorous French count; a nefarious French priest; and a gang of particularly feckless robbers-pursue their own schemes, stage their own impostures, and plot their own plots, their beaux' stratagem, leading Archer to conclude at the end of Act II, "We're like to have as many adventures in our inn as Don Quixote had in his."

At the New Theatre on Broadway, New York's gentry-merchants, bureaucrats, lawyers, and naval officers-paid for the box seats. Everyone else-servants, artisans, sailors, soldiers, and a handful of free blacks-sat in the pit. Joe, the slave of dancing master Henry Holt, probably worked backstage. James Alexander, a Freemason, may have walked down the aisle in procession with his brother lodge members, to sit together in a row, as Masons liked to do. Attorney Joseph Murray, an avid collector of English drama who happened to live more or less across the street from the theatre, must surely have attended with his wife, Grace, daughter of the former governor, their clothes for the evening laid out, perhaps, by their housekeeper, Mrs. Dimmock; their handsome house's front steps swept clean of flurrying snow by one of the Murrays' slaves: Jack, Congo, Dido, Adam, or Caesar. Perhaps Cuba, one of attorney John Chambers's slaves, entered the theatre quietly, before the curtain rose, to place a warming pan beneath the skirt of her mistress, Chambers's wife, Anna.

The playhouse on Broadway had much to offer in the way of conviviality, but the production on the night of the twelfth was not particularly polished; eighteenth-century New York, like the rest of the colonies, was a theatrical backwater. A 1709 decree by the Governor's Council had forbidden "play acting and prize-fighting," and the city's first recorded production did not take place until 1732, when another of Farquhar's comedies, The Recruiting Officer, was performed, with "the Part of Worthy acted by the ingenious Mr. Thomas Hearly," the mayor's barber and periwig maker. Nearly a decade later, the hairdressing thespian was no longer available. In 1741, for the New York debut of The Beaux' Stratagem, the part of Aimwell was "perform'd by a Person who never appear'd on any Stage before."

Still, the crowd, coming in from the cold, must have relished Farquhar's comedy, at once a pretzel of plot twists, a farce of love and deceit (and of the deceitfulness of lovers), a slightly bawdy parody of eighteenth-century courtship, and a rather bold critique of marriage. In Act IV, after having been wooed by Aimwell and Archer, Dorinda and Mrs. Sullen compare their suitors:

Dor: . . . my lover was upon his knees to me.

Mrs. Sul: And mine was upon his tiptoes to me.

Dor: Mine vowed to die for me.

Mrs. Sul: Mine swore to die with me.

Dor: Mine spoke the softest moving things.

Mrs. Sul: Mine had his moving things too.

Dor: Mine kissed my hand ten thousand times.

Mrs. Sul: Mine has all that pleasure to come.

Dor: Mine offered marriage.

Mrs. Sul: O Lard! d'ye call that a moving thing?

If Daniel Horsmanden attended the New Theatre on the night of February 12, he would have seen much that was familiar, uncomfortably familiar, in Aimwell and Archer, two men on the make, willing to say anything and to pass themselves off as wealthier than they were, plotting to marry rich women. Horsmanden was born in England in 1694, the eldest son of the rector of All Saints Church, in Purleigh, Essex. As a young man, he declined to inherit his father's position and determined instead on a legal career. In his twenties, while studying law in London, Horsmanden pursued his own beaux' stratagem on a trip to the fashionable resort town of Tunbridge Wells with his cousin, the Virginian William Byrd II, a widower in his forties who was desperately seeking a marriage alliance that might rescue him from debt. In Tunbridge Wells, Horsmanden courted "Miss B-n-y." Byrd, having recently failed to win the hand of Miss Mary Smith (in spite of boasting of his Virginia estate of 43,000 acres and 220 slaves), scouted about for another suitable wife while composing

Tunbrigalia, a book of poems celebrating the charms of several pretty Englishwomen of his close acquaintance, including Horsmanden's older sisters, Susanna (or "Suky") and Ursula (delightfully known as "Nutty Horsmanden"):

Thrice happy Wells! where Beauty's in such store,

When could'st thou boast an Horsmanden, a Hoar,

A Borrel, Lyndsey, Searle, and Thousands more?

William Byrd fancied himself a wit: after he and Horsmanden returned to London, Byrd wrote a love letter for his tongue-tied cousin Daniel. When Horsmanden told Byrd he "was going to Tunbridge again to endeavor to get Miss B-n-y," Byrd "lent him thirty guineas for his expedition." But Byrd's pen and pocketbook failed to win Horsmanden his suit. The mysterious Miss B-n-y turned him down.

In the 1710s, Horsmanden and Byrd dined together, drank together, attended the theatre together, and spent endless hours gossiping in London taverns and coffeehouses. And they went whoring together, as is made abundantly clear in Byrd's secret diary (written in an obscure shorthand and kept under lock and key), in entries like the one from June 26, 1718: "After dinner I put some things in order and then took a nap till 5 o'clock, when Daniel Horsmanden came and we went to the park, where we had appointed to meet some ladies but they failed. Then we went to Spring Gardens where we picked up two women and carried them into the arbor and ate some cold veal and about 10 o'clock we carried them to the bagnio, where we bathed and lay with them all night and I rogered mine twice and slept pretty well, but neglected my prayers."

William Byrd neglected his prayers more than once; he was a shattered man, compulsively rogering whores. During these painful, dissolute years of Byrd's life, young Daniel Horsmanden was his boon companion. By the diary's end, it's difficult not to raise an eyebrow at the homonym in Tunbrigalia, "When could'st thou boast an Horsmanden, a Hoar . . . ?"

Byrd, for all his sexual bravado, was mortified by his dependence on cheap prostitutes. He once wrote of himself, "The struggle between the Senate and the Plebeans in the Roman Commonwealth, or betweext the King and the Parliament in England, was never half so violent as the Civil war between this Hero's Principles and his Inclinations." Visiting prostitutes gave Byrd nightmares. In September 1719 he confided in his diary, "Daniel Horsmanden came again and we went to visit a whore but she was from home. . . . I dreamed I caused a coffin to be made for me to bury myself in but I changed my mind." What gave Byrd nightmares made Horsmanden sick. Six weeks after his first visit to a prostitute, the young law student was confined to his lodgings with "a sore leg." After another episode, he "had a swelled face." The "leg" might have been a euphemism: Horsmanden may have contracted syphilis, whose symptoms during the first two years after exposure include joint pain and markedly swollen glands-the "swelled face." In any event, Horsmanden's own rather tortured relationship with prostitutes, whom he tried in vain to give up, might explain why he didn't marry until 1747, at the age of fifty-three, and never fathered any children.

In 1720, the year after William Byrd left England for Virginia, Horsmanden lost his fortune, what little was left of his inheritance, in the South Sea Bubble. It was an awful blow. He continued to study at the Inns of Court but failed to earn much of a living or to recover his considerable South Sea losses by practicing law. He was broke. Eventually, as Horsmanden later explained, "I was Oblig'd to leave England."

In 1729, Horsmanden bought a book entitled A New Survey of the Globe, by Thomas Templeman. Templeman, true to an Englishman's sense of geography, reported only two kinds of information in his curious book: the size of landmasses and the distance of every important city in the world from London. Horsmanden, penniless and aimless, made his own survey of the globe, attempting to determine in what direction to head. He studied Templeman's figures closely. Finally, he decided to sail for Virginia, where his cousin William Byrd was a member of the Governor's Council.

But Horsmanden failed in Virginia, too. He was unable to gain admission to the bar, and he left after less than two years. By 1731, Daniel Horsmanden was on his way to New York City. Miles from London: 3,471.

"Have I been traversing the Ocean for so many weeks, to be sett down again in the country I quitted?" wondered another Englishman when he arrived in New York. "This cannot be a new town, in a new world, for such must be attended with many new objects, new faces, new manners, new customs, but here I can find nothing different from what I have quitted." More than three thousand miles from London, New York struck English visitors as uncannily familiar. "The dress and external appearance of the people is the same. The houses are in the stile we are accustomed to; within doors the furniture is all English or made after English fashions. The mode of living is the same." One visitor was flustered: "Where then shall I find any difference?" He found only one: "the greater number of the Blacks."

There was, of course, another difference. Compared to London, New York was no city at all. It was only a mile long and half a mile wide. In population, New York in 1741 was second only to Boston among colonial cities (and neck and neck with Philadelphia), but against London it was a hamlet. By Thomas Templeman's reckoning, "London contains about 105,000 Houses, 840,000 Souls." In 1741, New York boasted more like 1,500 houses and 10,000 souls. But nearly 2,000 were the souls of black folk, and their numbers almost always grabbed travelers' attention. (There were probably only about 15,000 blacks in eighteenth-century London, less than 2 percent of the population, compared to New York's 20 percent.)

Despite how almost entirely English the city may have at first appeared, New York was a jumble of cultures, languages, and religions. By 1731, it even had its own synagogue, the first in Britain's colonies. Peopled with Dutch, English, Welsh, Irish, Scots, and German settlers, French Huguenots, Portuguese Jews, and African slaves and "Spanish Negroes," New York was a frenzied, factious place. "The inhabitants of New York," a visiting English vicar observed, were more than half of them Dutch and therefore "habitually frugal, industrious, and parsimonious," but the rest were of so many "different nations, different languages, and different religions, it is almost impossible to give them any precise or determinate character."

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“A fascinating social and political history.” –The New York Times Book Review“Vivid and provocative; [Lepore] evokes eighteenth-century New York in all its moral and physical messiness.” –The New Yorker “A vivid and convincing account of the ‘plot’ and its aftermath.... [A] sober, meticulous, balanced book”–The Washington Post Book World “A historical study that is both intellectually rigorous and broadly accessible.... The type of book that we need to read and historians need to write, more often.”–Newsday“[Lepore] brings this terrifying period vividly to life.... A gripping read that shows how quickly fear spread through a city resting upon a terrible imbalance.”–Newark Star-Ledger

Descriere

From the award-winning author of "The Name of War" comes a gripping, illuminating account of an alleged 18th-century slave conspiracy to destroy New York City.

Premii

- ALA Notable Books Winner, 2006