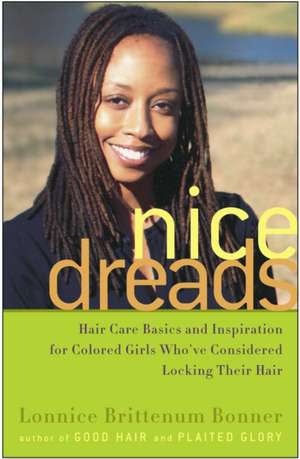

Nice Dreads: Hair Care Basics and Inspiration for Colored Girls Who've Considered Locking Their Hair

Autor Lonnice Brittenum Bonneren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2004

Perfect for women who want dreadlocks but aren’t sure how to start, or for those who’ve already started and want to know the best ways to keep hair healthy, Nice Dreads can help you grow your own lovely locks. From preparing for the haircut to everyday maintenance, Lonnice Brittenum Bonner tells you exactly what to expect, while photographs illustrate each stage of growth and showcase mature dreads in all their glory.

The author (who sports locks herself) knows firsthand the challenges of caring for this hairstyle; those intimidated by a drastic cut or shy about showing off the stages of early growth will find personal encouragement from someone who knows exactly how they feel—and how great they’ll look! Learn how to overcome your reservations and wear your style with pride.

Preț: 89.18 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 134

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.07€ • 18.55$ • 14.35£

17.07€ • 18.55$ • 14.35£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400051694

ISBN-10: 140005169X

Pagini: 144

Ilustrații: 30 B&W PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 9 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: HARMONY

ISBN-10: 140005169X

Pagini: 144

Ilustrații: 30 B&W PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 9 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: HARMONY

Notă biografică

Lonnice Brittenum Bonner began her writing career as a newspaper reporter with the Oakland Tribune. She has gone on to write several books on African American hair care, including Good Hair, Plaited Glory, and The Kitchen Beautician. She lives in Tennessee with her husband and son.

Extras

Chapter 1: Getting Started: Fruit of the Nappy Root

The main things folks want to know about starting locks are (1) Do I have to cut off my perm? and (2) Can you take them out?

First things first. Black women and haircuts have a stormy history. There’s a natural distrust of cutting, trimming, or putting any sort of sharp edge to our hair. I believe this is because we’ve been misled for so long about the fabled benefits of cutting that we’re just naturally wary. We’re trying to keep some hair, grow some hair, but when we go to the hairdresser we always end up giving them some. That’s because we swallow the correlation between touch-ups and trims; your new growth needs a touch-up and you trim the ends. Some hairdressers will throw game instead of skills and tell you that you need the trim because it will make your hair stronger, help it grow. What actually happens is that they trim whatever you grow so your hair remains in stasis. If your hair is overprocessed–a chronic condition in Black hair care–you’ll have chronic breakage, which guarantees you’ll never really see any meaningful increase in length. The trim is simply a cosmetic stave-off that keeps your hair presentable and makes their work look good when you leave the chair.

Another factor is fear of the unknown. We know how our perm is going to work; we’re accustomed to managing our expectations when it comes to touch-ups, breakage, and making nappy hair straight. All the energy has been directed toward achieving and maintaining straightness. The very idea of long lush hair that comes from the nappy coils we’ve been taught to remove is, well, an idea that takes many women some time to get used to.

I believe many Black women experience a visual oxymoron when they see long locked hair. It can’t be real because everyone knows that nappy hair doesn’t grow long enough to hang, it only grows out, as in an afro. Plus, the long hair fantasy–Rapunzel, Indian-Runs-in-My-Family, Goldilocks, Cher, Darchelle on Solid Gold, Jan and Marcia, the Asian Chick on Soul Train when Don Cornelius was the host–is all about long, straight hair or braid extensions tricked up to look like straight hair. Not dreadlocks. So when women see waist-length locks they see a comb and a dream; if they can comb it out and make it straight, they can get to the Promised Land.

I wish somebody had taken me in hand and told me to focus on what was important and forget the nonsense. The questions you should be asking when you are thinking about locking your hair should revolve around starting techniques and how you can expect your locks to look in the early weeks and months. You should know something about various locking methods, much as you would inquire about how to cultivate flowers you have never grown before. If you keep that analogy in mind, the ridiculous concern about whether or not you have to cut off your perm–or cut your hair, period–will make about as much sense as asking if you need to get rid of the concrete before you can plant a garden in the same spot.

DO I HAVE TO CUT OFF MY PERM?

The short answer is yes, but you’ll never look back in regret unless you weren’t really ready to go for it in the first place. If you want strong, aesthetically appealing locks, the perm just has to go.

CAN YOU TAKE LOCKS OUT?

I assume those who want to know how to do this remain deliriously excited about the possibility that waist-length locks can mean waist-length unlocked hair. I will categorically state that should you have the tenacity to pick apart an entire head of locks, you will not retain anything near the length of your locked hair. Get a grip and get yourself some braid extensions, which can be removed periodically with the goal of retaining the growth and length of your own hair. You’ll be happier.

ANATOMY OF A LOCK

Locked hair is a coily paradox. In order to form locks that flow down straight, the coils must be allowed to mesh and intertwine, encouraged to spin together into a cylindrical shaft of hair. Individual coiled strands grow and rest during the hair’s life cycle. When the hair is shed, the released coil remains intertwined in the lock. The unlocked hair at the base is alive and growing from the hair follicles; the body of each lock is akin to a large shaft of hair.

The average growth rate of hair is about one half-inch per month. Remember that this is an average rate; some hair grows faster or slower, and factors like age, health, pregnancy, and heredity have different effects on your hair’s growth rate.

Human hair grows in three stages. In the catogen stage, the hair prepares to emerge from the follicle. The growth phase, which can last from two to six years, is called the anogen stage. The resting stage, called the telogen stage, lasts for about three months, and then the hair is shed. Hair tends to grow faster in warm seasons than in colder ones.

The longer your hair’s anogen phase lasts, the more predisposed you are to have longer hair. For example, it takes about six years to grow waist-length hair from a short haircut, given a growth or anogen phase of at least six years. It’s fairly clear that women with waist-length hair have some genetic advantage going for them, but plenty of women have hair flowing pretty close to that length. How is this possible?

Well, in many cases, it isn’t so much about hair growth as it is about retention of that growth–it simply means that women with long, beautiful hair are working their program consistently. Those of us of African descent should also remember that tightly coiled hair tends to appear shorter, often half the length of straight hair of the same length. However, when these same strands intertwine and spin around each other, the hair is contained in cylindrical units and the ends are amazingly protected, and the hair, clean and conditioned, is retained along with the shed hair, spun into a lock like the finest of soft yarns.

It is helpful to compare the stages of lock development to those of the stages of individual hair strand growth, with sprouting, growing, resting, and shedding stages.

Five stages mark the process of your hair as the coils intertwine and spin themselves into cylindrical locks:

1. Coils—Coils resemble tightly coiled springs that look like baby spirals and can be as small as a watch spring or fluid and loose as fusilli. Hair can be as short or as long as one likes. The key factor here is that your hair is able to form and hold a coil, but the hair within the coil has not yet begun to intertwine or mesh.

What people find attractive about coils is that the hair tends to have sheen or shine because of the light that refracts off of the bend in each tiny ringlet. This is the first experience many African American women with extremely coily hair have with hair that naturally shines, without oiling or greasing. Coils work like bait, because often a woman sees another woman with a head full of coils and begins to consider the possibilities.

2. Sprouts and Buds—Crudely known among the philistines as Knots and Peas, Buckwheat Stage, Pickaninny Stage, Nappy Stage, “I wish she’d take that out” stage. Among the enlightened, initiated, erudite, urban hip chic set, cultural BAPs, and so on, your hair is recognized as Sprouting or Budding in that miraculous moment when the magic has begun. Those who are mothers can liken this to the terrible twos; it can be a challenging and creative time, or you can pull your hair out in frustration and give up. Would you give up your child because he was a terrible two? Naw, you just work with it and through it because you understand that what you do at this time sets the stage for the rest of his childhood development. The idea is to let him have his space while still setting boundaries, because trying to apply too much reason with a toddler is–well, you get the picture. Now apply that analogy to your sprouting and budding locks.

First, you shampoo your hair and notice that all of a sudden, the coils don’t all wash out like they used to. You may notice that some of your coils have little knots of hair in them, about the size of a small pea. This knot is more or less the nucleus of each lock; the hairs in your coils have begun to intertwine and interlace. Individual coils may seem puffy and lose their tightly coiled shape; this is part of the process and shouldn’t be disturbed. What is important here is to keep the original scalp partings, to allow the spinning process to become established for each individual lock. Don’t redivide your budding locks, twist them to death, or get to patting them down, trying to make your hair look “nice,” because you’ll just end up with a badly packed, busted-out do that is neither fish nor ’fro. You’ll look like you’re ashamed and embarrassed, and your hair will look downright bad because you’ll be cowering from it, walking around like hey, this isn’t me, this isn’t my hair. Lord, it sure is nappy. Don’t mind me, I’m on my way to get a relaxer. Oops! You caught me before I put my wig on this morning. And the anti-nap people will be on you like a duck on a junebug.

As I explained, buds are pea-shaped bubbles of hair that form either at the end of a small lock or in the middle of the budding lock. The bud is the nucleus of the intertwining transformation of hair. Sometimes buds become detached from the individual lock; these can be removed. Detached buds are little balls of hair that hang off the tips of some locks, suspended by a strand or two of hair. As long as the bud of hair is firmly meshed and attached to the rest of the lock, it is progressing fine. Some folks enjoy the funky, edgy look of wild little spirals and coils; others desperately want to avoid the Buckwheat phase.

Many women discover that indeed their hair has a coily texture and they’re now the closest they’ve ever been to having a true natural curl–albeit tight and tiny, but curls nonetheless. Budding can be a time when you learn a lot about your hair and have a good time with it as it grows into shoots, or you can go against the grain and be miserable and embarrassed because your hair is nappy. I received plenty of kudos from strangers during this phase. Some recognized that I was locking my hair; others didn’t know what I was doing with my hair, but they liked it.

3. Teen or Locking Stage—This is when the buds and sprouts truly begin to look like locks and few, if any, locks shampoo out or come out during sleep. The peas you saw and felt in the budding stage have expanded, and the hair has spun into a network of intertwining strands that extend throughout the length of individual locks. The locks may be soft and pliable or feel loosely meshed, according to your hair’s texture. This is the anogen or growing stage of lock development, and it extends into the lock’s mature stage. Shampooing doesn’t loosen these locks. They have dropped, which means they have developed enough to hang down versus defying gravity. This is when you start to relax and feel more confident about locking.

4. Mature Stage—Each individual lock is firmly meshed or tightly interwoven. Some loosely coiled hair textures may retain a small curl or coil at the end of the locks, but most will probably be closed at the ends. You will begin to see consistent growth because each lock has intertwined and contracted into a cylindrical shape. Think of each individual lock as a hair strand in itself. The new growth is contained in the loose hair at the base or root of each individual lock, and regular grooming encourages it to spin into an intertwined coil that will be integrated with the lock.

5. Beyond Maturity—Think of this stage as akin to the shedding stage of hair growth. After many years, depending on the care you have lavished on your locks, some locks may begin to thin and break off at the ends. For the most part, this deterioration can be minimized and controlled by monitoring the ends of your locks for signs of age and getting regular trims.

Remember, these are simply guidelines to development, not hair length. In fact, until your locks are mature, it is much better that you pay attention to the stages of development rather than length because any length you attain before the locks mature is likely to change or shorten as you continue to spin and groom your locks and the strands intertwine and contract into cylinders.

My preoccupation with length during my first year of locking caused me to hang on to my few inches of texturized hair and probably slowed the locking process. Hair hunger blinded me to the limp rat-tail twists trailing the plump budding locks. Sitting in Khamit Kinks loctician Doc’s chair and listening to him explain the futility of keeping two or three inches of old, played-out hair that only served to make my locks look raggedy was my salvation. The texturized, processed hair did not coil up with the virgin hair, and it never would. Sure, no one likes to hear that after getting through the buds and sprouts you’re going to be taken back to that length, but the overall look was such an aesthetic improvement that I didn’t miss the length at all. After the cutting my locks were even, they were tight, and just like Doc said, three months–heck, eight weeks–later, they rocked.

The main things folks want to know about starting locks are (1) Do I have to cut off my perm? and (2) Can you take them out?

First things first. Black women and haircuts have a stormy history. There’s a natural distrust of cutting, trimming, or putting any sort of sharp edge to our hair. I believe this is because we’ve been misled for so long about the fabled benefits of cutting that we’re just naturally wary. We’re trying to keep some hair, grow some hair, but when we go to the hairdresser we always end up giving them some. That’s because we swallow the correlation between touch-ups and trims; your new growth needs a touch-up and you trim the ends. Some hairdressers will throw game instead of skills and tell you that you need the trim because it will make your hair stronger, help it grow. What actually happens is that they trim whatever you grow so your hair remains in stasis. If your hair is overprocessed–a chronic condition in Black hair care–you’ll have chronic breakage, which guarantees you’ll never really see any meaningful increase in length. The trim is simply a cosmetic stave-off that keeps your hair presentable and makes their work look good when you leave the chair.

Another factor is fear of the unknown. We know how our perm is going to work; we’re accustomed to managing our expectations when it comes to touch-ups, breakage, and making nappy hair straight. All the energy has been directed toward achieving and maintaining straightness. The very idea of long lush hair that comes from the nappy coils we’ve been taught to remove is, well, an idea that takes many women some time to get used to.

I believe many Black women experience a visual oxymoron when they see long locked hair. It can’t be real because everyone knows that nappy hair doesn’t grow long enough to hang, it only grows out, as in an afro. Plus, the long hair fantasy–Rapunzel, Indian-Runs-in-My-Family, Goldilocks, Cher, Darchelle on Solid Gold, Jan and Marcia, the Asian Chick on Soul Train when Don Cornelius was the host–is all about long, straight hair or braid extensions tricked up to look like straight hair. Not dreadlocks. So when women see waist-length locks they see a comb and a dream; if they can comb it out and make it straight, they can get to the Promised Land.

I wish somebody had taken me in hand and told me to focus on what was important and forget the nonsense. The questions you should be asking when you are thinking about locking your hair should revolve around starting techniques and how you can expect your locks to look in the early weeks and months. You should know something about various locking methods, much as you would inquire about how to cultivate flowers you have never grown before. If you keep that analogy in mind, the ridiculous concern about whether or not you have to cut off your perm–or cut your hair, period–will make about as much sense as asking if you need to get rid of the concrete before you can plant a garden in the same spot.

DO I HAVE TO CUT OFF MY PERM?

The short answer is yes, but you’ll never look back in regret unless you weren’t really ready to go for it in the first place. If you want strong, aesthetically appealing locks, the perm just has to go.

CAN YOU TAKE LOCKS OUT?

I assume those who want to know how to do this remain deliriously excited about the possibility that waist-length locks can mean waist-length unlocked hair. I will categorically state that should you have the tenacity to pick apart an entire head of locks, you will not retain anything near the length of your locked hair. Get a grip and get yourself some braid extensions, which can be removed periodically with the goal of retaining the growth and length of your own hair. You’ll be happier.

ANATOMY OF A LOCK

Locked hair is a coily paradox. In order to form locks that flow down straight, the coils must be allowed to mesh and intertwine, encouraged to spin together into a cylindrical shaft of hair. Individual coiled strands grow and rest during the hair’s life cycle. When the hair is shed, the released coil remains intertwined in the lock. The unlocked hair at the base is alive and growing from the hair follicles; the body of each lock is akin to a large shaft of hair.

The average growth rate of hair is about one half-inch per month. Remember that this is an average rate; some hair grows faster or slower, and factors like age, health, pregnancy, and heredity have different effects on your hair’s growth rate.

Human hair grows in three stages. In the catogen stage, the hair prepares to emerge from the follicle. The growth phase, which can last from two to six years, is called the anogen stage. The resting stage, called the telogen stage, lasts for about three months, and then the hair is shed. Hair tends to grow faster in warm seasons than in colder ones.

The longer your hair’s anogen phase lasts, the more predisposed you are to have longer hair. For example, it takes about six years to grow waist-length hair from a short haircut, given a growth or anogen phase of at least six years. It’s fairly clear that women with waist-length hair have some genetic advantage going for them, but plenty of women have hair flowing pretty close to that length. How is this possible?

Well, in many cases, it isn’t so much about hair growth as it is about retention of that growth–it simply means that women with long, beautiful hair are working their program consistently. Those of us of African descent should also remember that tightly coiled hair tends to appear shorter, often half the length of straight hair of the same length. However, when these same strands intertwine and spin around each other, the hair is contained in cylindrical units and the ends are amazingly protected, and the hair, clean and conditioned, is retained along with the shed hair, spun into a lock like the finest of soft yarns.

It is helpful to compare the stages of lock development to those of the stages of individual hair strand growth, with sprouting, growing, resting, and shedding stages.

Five stages mark the process of your hair as the coils intertwine and spin themselves into cylindrical locks:

1. Coils—Coils resemble tightly coiled springs that look like baby spirals and can be as small as a watch spring or fluid and loose as fusilli. Hair can be as short or as long as one likes. The key factor here is that your hair is able to form and hold a coil, but the hair within the coil has not yet begun to intertwine or mesh.

What people find attractive about coils is that the hair tends to have sheen or shine because of the light that refracts off of the bend in each tiny ringlet. This is the first experience many African American women with extremely coily hair have with hair that naturally shines, without oiling or greasing. Coils work like bait, because often a woman sees another woman with a head full of coils and begins to consider the possibilities.

2. Sprouts and Buds—Crudely known among the philistines as Knots and Peas, Buckwheat Stage, Pickaninny Stage, Nappy Stage, “I wish she’d take that out” stage. Among the enlightened, initiated, erudite, urban hip chic set, cultural BAPs, and so on, your hair is recognized as Sprouting or Budding in that miraculous moment when the magic has begun. Those who are mothers can liken this to the terrible twos; it can be a challenging and creative time, or you can pull your hair out in frustration and give up. Would you give up your child because he was a terrible two? Naw, you just work with it and through it because you understand that what you do at this time sets the stage for the rest of his childhood development. The idea is to let him have his space while still setting boundaries, because trying to apply too much reason with a toddler is–well, you get the picture. Now apply that analogy to your sprouting and budding locks.

First, you shampoo your hair and notice that all of a sudden, the coils don’t all wash out like they used to. You may notice that some of your coils have little knots of hair in them, about the size of a small pea. This knot is more or less the nucleus of each lock; the hairs in your coils have begun to intertwine and interlace. Individual coils may seem puffy and lose their tightly coiled shape; this is part of the process and shouldn’t be disturbed. What is important here is to keep the original scalp partings, to allow the spinning process to become established for each individual lock. Don’t redivide your budding locks, twist them to death, or get to patting them down, trying to make your hair look “nice,” because you’ll just end up with a badly packed, busted-out do that is neither fish nor ’fro. You’ll look like you’re ashamed and embarrassed, and your hair will look downright bad because you’ll be cowering from it, walking around like hey, this isn’t me, this isn’t my hair. Lord, it sure is nappy. Don’t mind me, I’m on my way to get a relaxer. Oops! You caught me before I put my wig on this morning. And the anti-nap people will be on you like a duck on a junebug.

As I explained, buds are pea-shaped bubbles of hair that form either at the end of a small lock or in the middle of the budding lock. The bud is the nucleus of the intertwining transformation of hair. Sometimes buds become detached from the individual lock; these can be removed. Detached buds are little balls of hair that hang off the tips of some locks, suspended by a strand or two of hair. As long as the bud of hair is firmly meshed and attached to the rest of the lock, it is progressing fine. Some folks enjoy the funky, edgy look of wild little spirals and coils; others desperately want to avoid the Buckwheat phase.

Many women discover that indeed their hair has a coily texture and they’re now the closest they’ve ever been to having a true natural curl–albeit tight and tiny, but curls nonetheless. Budding can be a time when you learn a lot about your hair and have a good time with it as it grows into shoots, or you can go against the grain and be miserable and embarrassed because your hair is nappy. I received plenty of kudos from strangers during this phase. Some recognized that I was locking my hair; others didn’t know what I was doing with my hair, but they liked it.

3. Teen or Locking Stage—This is when the buds and sprouts truly begin to look like locks and few, if any, locks shampoo out or come out during sleep. The peas you saw and felt in the budding stage have expanded, and the hair has spun into a network of intertwining strands that extend throughout the length of individual locks. The locks may be soft and pliable or feel loosely meshed, according to your hair’s texture. This is the anogen or growing stage of lock development, and it extends into the lock’s mature stage. Shampooing doesn’t loosen these locks. They have dropped, which means they have developed enough to hang down versus defying gravity. This is when you start to relax and feel more confident about locking.

4. Mature Stage—Each individual lock is firmly meshed or tightly interwoven. Some loosely coiled hair textures may retain a small curl or coil at the end of the locks, but most will probably be closed at the ends. You will begin to see consistent growth because each lock has intertwined and contracted into a cylindrical shape. Think of each individual lock as a hair strand in itself. The new growth is contained in the loose hair at the base or root of each individual lock, and regular grooming encourages it to spin into an intertwined coil that will be integrated with the lock.

5. Beyond Maturity—Think of this stage as akin to the shedding stage of hair growth. After many years, depending on the care you have lavished on your locks, some locks may begin to thin and break off at the ends. For the most part, this deterioration can be minimized and controlled by monitoring the ends of your locks for signs of age and getting regular trims.

Remember, these are simply guidelines to development, not hair length. In fact, until your locks are mature, it is much better that you pay attention to the stages of development rather than length because any length you attain before the locks mature is likely to change or shorten as you continue to spin and groom your locks and the strands intertwine and contract into cylinders.

My preoccupation with length during my first year of locking caused me to hang on to my few inches of texturized hair and probably slowed the locking process. Hair hunger blinded me to the limp rat-tail twists trailing the plump budding locks. Sitting in Khamit Kinks loctician Doc’s chair and listening to him explain the futility of keeping two or three inches of old, played-out hair that only served to make my locks look raggedy was my salvation. The texturized, processed hair did not coil up with the virgin hair, and it never would. Sure, no one likes to hear that after getting through the buds and sprouts you’re going to be taken back to that length, but the overall look was such an aesthetic improvement that I didn’t miss the length at all. After the cutting my locks were even, they were tight, and just like Doc said, three months–heck, eight weeks–later, they rocked.