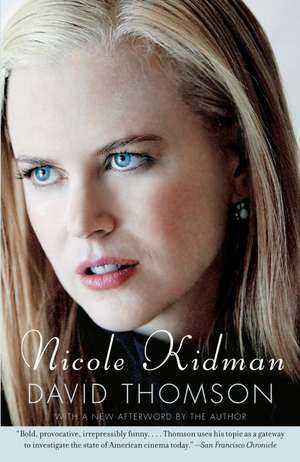

Nicole Kidman

Autor David Thomsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2007

Preț: 88.65 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 133

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.97€ • 17.53$ • 14.12£

16.97€ • 17.53$ • 14.12£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400077816

ISBN-10: 1400077818

Pagini: 286

Ilustrații: 10 PHOTOGRAPHS

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 1400077818

Pagini: 286

Ilustrații: 10 PHOTOGRAPHS

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

John Heilpern is the author of the classic book about theater Conference of the Birds: The Story of Peter Brook in Africa and of How Good is David Mamet, Anyway?, a collection of his theater essays and reviews. Born in England and educated at Oxford, his interviews for The Observer (London) received a British Press Award. In 1980 he moved to New York, where he became a weekly columnist for The Times of London. An adjunct professor of drama at Columbia University, he is drama critic for the New York Observer.

Extras

Chapter 1

Strangers

I am talking to an Australian, a woman, about Nicole Kidman, and the crucial mystery is there at the start: “I’ve known her twenty years, and I’ve spent a staggering amount of time with her, but I feel I don’t know her. Because what she gives you is what you want. A lot of actors are like that. They don’t exist when they aren’t playing a part.”

This book is about acting and about an actress, but it must also study what happens to anyone beholding an actress—the spectator, the audience, or ourselves in any of our voyeur roles. And the most important thing in that vexed transaction is the way the actress and the spectator must remain strangers. That’s how the magic works. Without that guarantee, the dangers of “relationship” are grisly and absurd—they range from illicit touching to murder. For there cannot be this pitch of irrational desire without that rigorous apartness, provided by a hundred feet of warm space in a theater, and by that astonishing human invention, the screen, at the movies. And just as the movies were never simply an art or a show, a drama or narrative, but the manifestation of desire, so the screen is both barrier and open sesame.

The thing that permits witness—seeing her, being so intimate—is also the outline of a prison.

This predicament reminds me of a moment in Citizen Kane. The reporter, Thompson, goes to visit Bernstein, an old man who was Charlie Kane’s right-hand man and who is now chairman of the board of the Kane companies. Thompson asks him if he knows what “Rosebud,” Kane’s last word, might have referred to. Some girl? wonders Bernstein. “There were a lot of them back in the early days . . .” Thompson thinks it unlikely that a chance meeting fifty years ago could have prompted a solemn last word. But Bernstein disputes this: “A fellow will remember a lot of things you wouldn’t think he’d remember.

“You take me,” he says. “One day, back in 1896, I was crossing over to Jersey on the ferry, and as we pulled out, there was another ferry pulling in, and on it there was a girl waiting to get off. A white dress she had on. She was carrying a white parasol. I only saw her for one second. She didn’t see me at all, but I’ll bet a month hasn’t gone by since, that I haven’t thought of that girl.”

Bernstein seems to be single—to all intents and purposes he was married to Charlie Kane. I daresay some beaverish subtextual critic could argue that the girl in the parasol stands for the sheet of paper on which the young Kane sets out his “Declaration of Principles.” Yet the reason why the anecdote (and the actor Everett Sloane’s ecstatic yet heartbroken delivery of it) has stayed with me is that it embodies the principle of hopeless desire, and endless hope, on which the movies are founded. Of course, most little boys (even those of an advanced age) feel pressing hormonal urges to satisfy desire. And I would not exile myself from that gang. Still, there is another calling—and film is often its banner—that consists of those who would always protect and preserve desire by ensuring that it is never satisfied. For those of that persuasion—and it is more than merely sexual—there is no art more piquant than the films of Luis Buñuel, one of which is actually entitled That Obscure Object of Desire. (In that light, let me alert you not to miss this book’s vision of Belle de Jour as if Nicole Kidman had played in it. In fact, I have dreamed this film with such intensity that it matters to me more than many films I actually have to see.)

Anyway, the subject of this book is Nicole Kidman. And I should own up straightaway that, yes, I like Nicole Kidman very much. When I tell people that, sometimes they leer and ask, “Do you love her?” And my answer is clear: Yes, of course, I love her—so long as I do not have to meet her.

Now, that proviso could be thought hostile; it might even conjure up possibilities of an aggressive streak, a harsh laugh, or even a regrettable body odor in Ms. Kidman that one would sooner avoid. That’s not what I am talking about, and it’s nothing I have ever heard suggested. I suspect she is as fragrant as spring, as ripe as summer, as sad as autumn, and as coldly possessed as winter. Much more to the point, you see, I am suggesting that getting to know actresses is a depressing sport. The history of Hollywood could be composed as a volume of melancholy memoirs all made ruinous when Alfred Hitchcock, say, actually met Tippi Hedren, or whomever. Actors and actresses are seldom marriageable and too little thanks has been offered to the profession for the steadfast way in which its members sacrifice themselves to each other. It is as if they understood the spell put upon them and knew that anyone raised in any other craft or system would collapse with incredulity if confronted by the endless fascination performers only find in themselves. They go to the altar— they do not alter.

Laboring with movies for six decades now, I am coming to the conclusion that this medium has been steadily misunderstood. Yes, it has some semblance of being an entertainment, a business, an art, a storytelling machine—and so on. But all of those semirespectable identities help obscure what is most precious and unique, and what is absolutely formulated by the simultaneous presence and denial on the screen: that a movie is a dream, a sleepwalking, a séance, in which we seem to mingle with ghosts. And here is the vital spark: whenever we seem within reach of these intensely desirable creatures, their states and moods, we ourselves resemble actors as they come close to redeeming their terrible vacancy by assuming parts, or roles.

In other words, acting and being at the movies are mirror images, and they are the persistent, infectious forms of nonbeing that have steadily undermined the thing once known as real life in the last hundred years. So the study of acting is less a record of creative process or artistic eloquence; it is a kind of drug-taking, very bad for us—yet absolutely incurable. I daresay this sounds a touch odd or obscure at first—or maybe it is just alarming—but it will creep up on you as this book proceeds. It is an insidious process, such as ought to be banned everywhere by churches, schools, parents, and the law (all those institutions that claim to be looking after us). On the other hand, it has entered the bloodstream; it goes on and on—and some would say we are hopelessly lost to fantasy already, and so thoroughly immersed in desire that something like real, practical improvement (surely a good thing?) has been befuddled.

And yet there is something enormously positive and creative that can come from it, a mixture of calm and insight. It is to see that we can entertain the idea of strangers in our minds—if only by wanting to be them, or be like them. The movies are about beholding strangers and in the process losing touch with those real people one happens to meet and has the chance of knowing. I believe now that I learned to fall in love by watching actors and actresses, and that is not a wholesome training. It is one that prompts a rapid dissatisfaction with the thing or the person present, or possessed. Their charm can never compete with the allure of the unattainable. Thus, to follow desire is to give up the ghost on relationship. Just as you reflect on that, and consider how far it is a restlessness that has you in its grip, you will remember from so many life lessons that it is also a very bad thing. This is very dangerous territory, even if most of us are already there—in other words, there is still a weird kind of polite respectability that is possible in life from denying it.

Let me tell you a story that helps explain this. In my last book about the movies, The Whole Equation, I was feeling my way toward this point of view, and I included a chapter, “By a Nose,” which concerned Nicole Kidman in The Hours. I offered it as a testament from a fan, a love letter, from someone in the dark to one of those beauties in the light. As a matter of fact, she was not my true favorite. Indeed, I feared in advance—and I still think it likely— that if I were to write about my real favorites, my movie sweethearts, I would be rendered speechless and helpless, because the fantastic intimacy is too great. So, yes, I do like Nicole Kidman, but not quite as much as Catherine Deneuve, Julia Roberts, Grace Kelly, and Donna Reed (I am tracing sweetheartism back to when I was about eleven).

Nevertheless, when Michiko Kakutani reviewed The Whole Equation in the New York Times, she saw fit to call my “crush” on Kidman ridiculous. (You see how brave authors must be.) Well, maybe, but I am owning up to it, because I think it is the only way to get at things that need to be said (somehow in all the turmoil of desire, I have retained the semblance of some educational purpose). Going to the movies and believing may be foolish, or worse. It may be crazy. But I think even book reviewers have been formed by its risk.

At the moment, as I try to write this, just behind one layer of my computer screen there is an AOL home page in which I have the chance to catch up with the diet secrets of Jessica Simpson and Denise Richards. There are their pictures—lean yet carnal—Jessica and Denise, would-bes who maintain a presence not always in movies, per se, or shows, but in celebrity newsbreaks, in fashion follies, dietary secrets, and scandal scoops. That supporting atmosphere is as old as movies, but it is more intense now just because of the Internet. Moreover, one of the most intriguing things about Nicole Kidman is that at least one of her ample size ten feet is firmly planted in that electronic wasteland. Nicole can be great and serious. She is an Oscar winner. Sometimes you can believe she might play any part. But she is also heart-and-soul a sexual celebrity, someone who, close to forty, is not just ready or eager but proud to give her sexy come-hither look to some magazine. Her appetite for life is not snobbish, or elitist, not ready to act her age. I mean, we do not see Vanessa Redgrave or Meryl Streep or Miranda Richardson (her colleagues as actors) in glamour pictures, not these days. Yet on the Internet you can get a lubricious roundup of every nude or seminude scene Nicole has ever done. You may know the curve of her bottom as well as you know your child’s brow. Nicole does expensive perfume ads; she does eye-candy covers; she will drop her clothes if only to air out that elegant Australian body (she does wish she were a few inches shorter, with those inches added on her breasts—but there you are, she is very human). That’s another reason why the world, for just a few years, has been crazy about her. How can I put it? Let’s just say she has not flinched from the duty of a great celebrity to be on public display. There are thousands of hits on her every day, not real hits, blows to the body, but the hits of our day, the fantasy contacts, the “I want to know more about Nicole” pressures on the mouse.

I daresay that as she grows older she will become weathered, a great lined old lady like Katharine Hepburn, a mistress of the art of acting and of the cult of her own high-mindedness. But this book was conceived and composed while she was still hot and hittable, and likely to be in every tabloid and on every magazine cover because the rumor industry—our essential river of story—could not leave her alone. Even if she becomes that great old lady, Dame Nicole Kidman, in those greedy eyes of hers the hunger will persist for the good old days when she was in everyone’s virtual bed. Millions more have had that palpable illusion help them make it through the night.

But note this, please. She is, as I write, in addition to everything else, a fun-loving thirty-nine-year-old with a cheerful eighteen-year- old’s attitude. I mean, she has not grown up or old—she has been kept young by attention. She would like to go skiing; and for a moment at least she might like to go with you! One of the more hideous things about what happens to actresses and celebrities is that, somewhere around forty, the tissue-paper safety net dissolves and the star suddenly has to go from being a nymph to being an adult. Nicole’s own name is already part of that terrible future, and I daresay she wakes up some nights screaming because she felt it was about to happen. (Not that I can be there to witness it—or stop imagining it.)

But just because of that vulnerability, it would be improper or cruel for a biography to grind too remorselessly close or fine. Let her live while she can. Why pretend to be censorious over every fleeting love affair, or any toke she might take? Let time take its course. Let her awkward teenage years off lightly, and know that, as with all actors and actresses, the idea of the real life is, anyway, the ultimate tragedy, the terminal desolation. They are too busy being the center of attention to have a life. So, I will be gentle and tender on passing over some things. If I elect to say little about the movie Far and Away, for instance, then understand that there are films made for no other reason than that the people involved were in love. It is their business. Sometimes it ends up looking like Pierrot le Fou or an Ingmar Bergman picture. Sometimes it’s Far and Away— enough said. It is so very much more interesting to explore films not actually made, such as Nicole Kidman as Belle de Jour or Nicole Kidman in Rebecca. In a way, the best admiration we can give her is to imagine other parts she might play. That is adding to her creative soul.

One final word. You will want to know, “Did I talk to her?,” no matter how ardently I have stressed the point about staying strangers. Well, at the very outset, I approached her through her representatives, asking for an interview. There was silence, and then there was a Well, yes, she is interested. But she was so busy . . . and time passed. So I began to write the book, and I had an entire draft done before hearing a word from her. What happened? Well, what do you think happened? One day in February 2006, my phone rang and I heard, “It’s Nicole,” as if she were a languid, superior, but amused prefect who had called a naughty boy to her study to see what he had been up to.

From the Hardcover edition.

Strangers

I am talking to an Australian, a woman, about Nicole Kidman, and the crucial mystery is there at the start: “I’ve known her twenty years, and I’ve spent a staggering amount of time with her, but I feel I don’t know her. Because what she gives you is what you want. A lot of actors are like that. They don’t exist when they aren’t playing a part.”

This book is about acting and about an actress, but it must also study what happens to anyone beholding an actress—the spectator, the audience, or ourselves in any of our voyeur roles. And the most important thing in that vexed transaction is the way the actress and the spectator must remain strangers. That’s how the magic works. Without that guarantee, the dangers of “relationship” are grisly and absurd—they range from illicit touching to murder. For there cannot be this pitch of irrational desire without that rigorous apartness, provided by a hundred feet of warm space in a theater, and by that astonishing human invention, the screen, at the movies. And just as the movies were never simply an art or a show, a drama or narrative, but the manifestation of desire, so the screen is both barrier and open sesame.

The thing that permits witness—seeing her, being so intimate—is also the outline of a prison.

This predicament reminds me of a moment in Citizen Kane. The reporter, Thompson, goes to visit Bernstein, an old man who was Charlie Kane’s right-hand man and who is now chairman of the board of the Kane companies. Thompson asks him if he knows what “Rosebud,” Kane’s last word, might have referred to. Some girl? wonders Bernstein. “There were a lot of them back in the early days . . .” Thompson thinks it unlikely that a chance meeting fifty years ago could have prompted a solemn last word. But Bernstein disputes this: “A fellow will remember a lot of things you wouldn’t think he’d remember.

“You take me,” he says. “One day, back in 1896, I was crossing over to Jersey on the ferry, and as we pulled out, there was another ferry pulling in, and on it there was a girl waiting to get off. A white dress she had on. She was carrying a white parasol. I only saw her for one second. She didn’t see me at all, but I’ll bet a month hasn’t gone by since, that I haven’t thought of that girl.”

Bernstein seems to be single—to all intents and purposes he was married to Charlie Kane. I daresay some beaverish subtextual critic could argue that the girl in the parasol stands for the sheet of paper on which the young Kane sets out his “Declaration of Principles.” Yet the reason why the anecdote (and the actor Everett Sloane’s ecstatic yet heartbroken delivery of it) has stayed with me is that it embodies the principle of hopeless desire, and endless hope, on which the movies are founded. Of course, most little boys (even those of an advanced age) feel pressing hormonal urges to satisfy desire. And I would not exile myself from that gang. Still, there is another calling—and film is often its banner—that consists of those who would always protect and preserve desire by ensuring that it is never satisfied. For those of that persuasion—and it is more than merely sexual—there is no art more piquant than the films of Luis Buñuel, one of which is actually entitled That Obscure Object of Desire. (In that light, let me alert you not to miss this book’s vision of Belle de Jour as if Nicole Kidman had played in it. In fact, I have dreamed this film with such intensity that it matters to me more than many films I actually have to see.)

Anyway, the subject of this book is Nicole Kidman. And I should own up straightaway that, yes, I like Nicole Kidman very much. When I tell people that, sometimes they leer and ask, “Do you love her?” And my answer is clear: Yes, of course, I love her—so long as I do not have to meet her.

Now, that proviso could be thought hostile; it might even conjure up possibilities of an aggressive streak, a harsh laugh, or even a regrettable body odor in Ms. Kidman that one would sooner avoid. That’s not what I am talking about, and it’s nothing I have ever heard suggested. I suspect she is as fragrant as spring, as ripe as summer, as sad as autumn, and as coldly possessed as winter. Much more to the point, you see, I am suggesting that getting to know actresses is a depressing sport. The history of Hollywood could be composed as a volume of melancholy memoirs all made ruinous when Alfred Hitchcock, say, actually met Tippi Hedren, or whomever. Actors and actresses are seldom marriageable and too little thanks has been offered to the profession for the steadfast way in which its members sacrifice themselves to each other. It is as if they understood the spell put upon them and knew that anyone raised in any other craft or system would collapse with incredulity if confronted by the endless fascination performers only find in themselves. They go to the altar— they do not alter.

Laboring with movies for six decades now, I am coming to the conclusion that this medium has been steadily misunderstood. Yes, it has some semblance of being an entertainment, a business, an art, a storytelling machine—and so on. But all of those semirespectable identities help obscure what is most precious and unique, and what is absolutely formulated by the simultaneous presence and denial on the screen: that a movie is a dream, a sleepwalking, a séance, in which we seem to mingle with ghosts. And here is the vital spark: whenever we seem within reach of these intensely desirable creatures, their states and moods, we ourselves resemble actors as they come close to redeeming their terrible vacancy by assuming parts, or roles.

In other words, acting and being at the movies are mirror images, and they are the persistent, infectious forms of nonbeing that have steadily undermined the thing once known as real life in the last hundred years. So the study of acting is less a record of creative process or artistic eloquence; it is a kind of drug-taking, very bad for us—yet absolutely incurable. I daresay this sounds a touch odd or obscure at first—or maybe it is just alarming—but it will creep up on you as this book proceeds. It is an insidious process, such as ought to be banned everywhere by churches, schools, parents, and the law (all those institutions that claim to be looking after us). On the other hand, it has entered the bloodstream; it goes on and on—and some would say we are hopelessly lost to fantasy already, and so thoroughly immersed in desire that something like real, practical improvement (surely a good thing?) has been befuddled.

And yet there is something enormously positive and creative that can come from it, a mixture of calm and insight. It is to see that we can entertain the idea of strangers in our minds—if only by wanting to be them, or be like them. The movies are about beholding strangers and in the process losing touch with those real people one happens to meet and has the chance of knowing. I believe now that I learned to fall in love by watching actors and actresses, and that is not a wholesome training. It is one that prompts a rapid dissatisfaction with the thing or the person present, or possessed. Their charm can never compete with the allure of the unattainable. Thus, to follow desire is to give up the ghost on relationship. Just as you reflect on that, and consider how far it is a restlessness that has you in its grip, you will remember from so many life lessons that it is also a very bad thing. This is very dangerous territory, even if most of us are already there—in other words, there is still a weird kind of polite respectability that is possible in life from denying it.

Let me tell you a story that helps explain this. In my last book about the movies, The Whole Equation, I was feeling my way toward this point of view, and I included a chapter, “By a Nose,” which concerned Nicole Kidman in The Hours. I offered it as a testament from a fan, a love letter, from someone in the dark to one of those beauties in the light. As a matter of fact, she was not my true favorite. Indeed, I feared in advance—and I still think it likely— that if I were to write about my real favorites, my movie sweethearts, I would be rendered speechless and helpless, because the fantastic intimacy is too great. So, yes, I do like Nicole Kidman, but not quite as much as Catherine Deneuve, Julia Roberts, Grace Kelly, and Donna Reed (I am tracing sweetheartism back to when I was about eleven).

Nevertheless, when Michiko Kakutani reviewed The Whole Equation in the New York Times, she saw fit to call my “crush” on Kidman ridiculous. (You see how brave authors must be.) Well, maybe, but I am owning up to it, because I think it is the only way to get at things that need to be said (somehow in all the turmoil of desire, I have retained the semblance of some educational purpose). Going to the movies and believing may be foolish, or worse. It may be crazy. But I think even book reviewers have been formed by its risk.

At the moment, as I try to write this, just behind one layer of my computer screen there is an AOL home page in which I have the chance to catch up with the diet secrets of Jessica Simpson and Denise Richards. There are their pictures—lean yet carnal—Jessica and Denise, would-bes who maintain a presence not always in movies, per se, or shows, but in celebrity newsbreaks, in fashion follies, dietary secrets, and scandal scoops. That supporting atmosphere is as old as movies, but it is more intense now just because of the Internet. Moreover, one of the most intriguing things about Nicole Kidman is that at least one of her ample size ten feet is firmly planted in that electronic wasteland. Nicole can be great and serious. She is an Oscar winner. Sometimes you can believe she might play any part. But she is also heart-and-soul a sexual celebrity, someone who, close to forty, is not just ready or eager but proud to give her sexy come-hither look to some magazine. Her appetite for life is not snobbish, or elitist, not ready to act her age. I mean, we do not see Vanessa Redgrave or Meryl Streep or Miranda Richardson (her colleagues as actors) in glamour pictures, not these days. Yet on the Internet you can get a lubricious roundup of every nude or seminude scene Nicole has ever done. You may know the curve of her bottom as well as you know your child’s brow. Nicole does expensive perfume ads; she does eye-candy covers; she will drop her clothes if only to air out that elegant Australian body (she does wish she were a few inches shorter, with those inches added on her breasts—but there you are, she is very human). That’s another reason why the world, for just a few years, has been crazy about her. How can I put it? Let’s just say she has not flinched from the duty of a great celebrity to be on public display. There are thousands of hits on her every day, not real hits, blows to the body, but the hits of our day, the fantasy contacts, the “I want to know more about Nicole” pressures on the mouse.

I daresay that as she grows older she will become weathered, a great lined old lady like Katharine Hepburn, a mistress of the art of acting and of the cult of her own high-mindedness. But this book was conceived and composed while she was still hot and hittable, and likely to be in every tabloid and on every magazine cover because the rumor industry—our essential river of story—could not leave her alone. Even if she becomes that great old lady, Dame Nicole Kidman, in those greedy eyes of hers the hunger will persist for the good old days when she was in everyone’s virtual bed. Millions more have had that palpable illusion help them make it through the night.

But note this, please. She is, as I write, in addition to everything else, a fun-loving thirty-nine-year-old with a cheerful eighteen-year- old’s attitude. I mean, she has not grown up or old—she has been kept young by attention. She would like to go skiing; and for a moment at least she might like to go with you! One of the more hideous things about what happens to actresses and celebrities is that, somewhere around forty, the tissue-paper safety net dissolves and the star suddenly has to go from being a nymph to being an adult. Nicole’s own name is already part of that terrible future, and I daresay she wakes up some nights screaming because she felt it was about to happen. (Not that I can be there to witness it—or stop imagining it.)

But just because of that vulnerability, it would be improper or cruel for a biography to grind too remorselessly close or fine. Let her live while she can. Why pretend to be censorious over every fleeting love affair, or any toke she might take? Let time take its course. Let her awkward teenage years off lightly, and know that, as with all actors and actresses, the idea of the real life is, anyway, the ultimate tragedy, the terminal desolation. They are too busy being the center of attention to have a life. So, I will be gentle and tender on passing over some things. If I elect to say little about the movie Far and Away, for instance, then understand that there are films made for no other reason than that the people involved were in love. It is their business. Sometimes it ends up looking like Pierrot le Fou or an Ingmar Bergman picture. Sometimes it’s Far and Away— enough said. It is so very much more interesting to explore films not actually made, such as Nicole Kidman as Belle de Jour or Nicole Kidman in Rebecca. In a way, the best admiration we can give her is to imagine other parts she might play. That is adding to her creative soul.

One final word. You will want to know, “Did I talk to her?,” no matter how ardently I have stressed the point about staying strangers. Well, at the very outset, I approached her through her representatives, asking for an interview. There was silence, and then there was a Well, yes, she is interested. But she was so busy . . . and time passed. So I began to write the book, and I had an entire draft done before hearing a word from her. What happened? Well, what do you think happened? One day in February 2006, my phone rang and I heard, “It’s Nicole,” as if she were a languid, superior, but amused prefect who had called a naughty boy to her study to see what he had been up to.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Compulsively readable . . . an entertaining romp through [Nicole Kidman’s] life and career that’s also a smart commentary on celeb culture.”

--Christopher Kelly, The Star-Telegram

“Illuminating . . . part astute analysis of our relationship to the film image and our cultural fixation on celebrity and part insightful film criticism . . . [a] starry-eyed love letter.”

--Tara Ison, Los Angeles Times Book Review

“Thomson is probably the single most gifted film writer alive . . . an extraordinarily knowing meditation on movies as purveyors of dreams and desires”

--Jeff Simon, The Buffalo News

“Rewrites the celebrity biography into a savvy exploration of myth-making . . . Dangerously smart, Thomson never lectures. He throws little gems and thought-provoking insights in the midst of the liveliest conversation. A passionate storyteller, he peppers his analyses with sassy anecdotes . . . and biting remarks on politics, celebrity culture and their commodification of human dramas. Bold, provocative, irrepressibly funny . . . will delight those who enjoy a book that has guts and brains.”

--Cécile Alduy, San Francisco Chronicle

“Film critic David Thomson has a crush on Kidman and he doesn’t care who knows . . . a shrewd book about the nature of screen acting, fantasy and stardom.”

--Newsday

From the Hardcover edition.

--Christopher Kelly, The Star-Telegram

“Illuminating . . . part astute analysis of our relationship to the film image and our cultural fixation on celebrity and part insightful film criticism . . . [a] starry-eyed love letter.”

--Tara Ison, Los Angeles Times Book Review

“Thomson is probably the single most gifted film writer alive . . . an extraordinarily knowing meditation on movies as purveyors of dreams and desires”

--Jeff Simon, The Buffalo News

“Rewrites the celebrity biography into a savvy exploration of myth-making . . . Dangerously smart, Thomson never lectures. He throws little gems and thought-provoking insights in the midst of the liveliest conversation. A passionate storyteller, he peppers his analyses with sassy anecdotes . . . and biting remarks on politics, celebrity culture and their commodification of human dramas. Bold, provocative, irrepressibly funny . . . will delight those who enjoy a book that has guts and brains.”

--Cécile Alduy, San Francisco Chronicle

“Film critic David Thomson has a crush on Kidman and he doesn’t care who knows . . . a shrewd book about the nature of screen acting, fantasy and stardom.”

--Newsday

From the Hardcover edition.