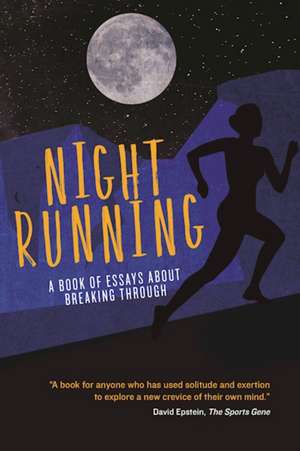

Night Running: A Book of Essays About Breaking Through

Autor Pete Danko, Kelsey Eiland, Bonnie Ford, Steve Kettmann, Anne Milligan, Emily Mitchell, Joy Russo-Schoenfield, Vanessa Runs, Dahlia Scheindlin, Heather Semb, T.J. Quinnen Limba Engleză Paperback – 13 iun 2016

This daring volume combines the best of writing on running with the appeal of the best literary writing, essays that take in the sights and sounds and smells of real life, of real risk, of real pain and of real elation. Emphasizing female voices, this collection of eleven personal essays set in different countries around the world offers a deep but accessible look at the power of running in our lives to make us feel more and to see ourselves in a new light.

From acclaimed novelist Emily Mitchell and Portland attorney Anne Milligan to author Vanessa Runs and ESPN reporter Bonnie Ford, a diverse lineup of writers captures a variety of perspectives on running at night. These are stories that can inspire people of all ages and backgrounds to take on a thrilling new challenge. The contributors all have distinct tales to tell, but each brings a freshness and depth to their experiences that make Night Running a necessary part of every runner’s library - and a valuable addition to the reading lists of all thoughtful readers.

From acclaimed novelist Emily Mitchell and Portland attorney Anne Milligan to author Vanessa Runs and ESPN reporter Bonnie Ford, a diverse lineup of writers captures a variety of perspectives on running at night. These are stories that can inspire people of all ages and backgrounds to take on a thrilling new challenge. The contributors all have distinct tales to tell, but each brings a freshness and depth to their experiences that make Night Running a necessary part of every runner’s library - and a valuable addition to the reading lists of all thoughtful readers.

Preț: 78.33 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 117

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.99€ • 15.59$ • 12.38£

14.99€ • 15.59$ • 12.38£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780985419073

ISBN-10: 0985419075

Pagini: 144

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.16 kg

Editura: Wellstone Books

Colecția Wellstone Books

ISBN-10: 0985419075

Pagini: 144

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.16 kg

Editura: Wellstone Books

Colecția Wellstone Books

Recenzii

"Running in the dark paradoxically heightens the senses and even pathways to the soul. The essays in Night Running explore this previously ignored phenomenon in many unexpected and revealing ways."

-Amby Burfoot, winner of the 1968 Boston Marathon and for years the Editor-in-Chief of Runner's World

"A book for anyone who has used solitude and exertion to explore a new crevice of their own mind. Fear, exhilaration, anger, accomplishment, despair, euphoria&mdashevery one of these emotions is distilled in Night Running.

-David Epstein, The Sports Gene

"Night Running captures in a myriad of ways the essence of running: solitude, self-discovery and the exhilaration of a momentary escape from the banal."

-Sandy Alderson, general manager, New York Mets, 2:53 marathoner

"A fascinating and eclectic collection! In Night Running, eleven essayists express, with bracing honesty, how a simple act of will—running in the dark—can free body and mind from fear, and restore the spirit."

-Novelist Mary Volmer, author of Crown of Dust and Reliance, Illinois

"Good writing, like a good run, should feel effortless even when ambitious. This collection of essays finds its stride early as it illuminates, entertains and often dazzles."

-Daniel Brown, author of The Big 50: San Francisco Giants: The Men and Moments That Made the San Francisco Giants

-Amby Burfoot, winner of the 1968 Boston Marathon and for years the Editor-in-Chief of Runner's World

"A book for anyone who has used solitude and exertion to explore a new crevice of their own mind. Fear, exhilaration, anger, accomplishment, despair, euphoria&mdashevery one of these emotions is distilled in Night Running.

-David Epstein, The Sports Gene

"Night Running captures in a myriad of ways the essence of running: solitude, self-discovery and the exhilaration of a momentary escape from the banal."

-Sandy Alderson, general manager, New York Mets, 2:53 marathoner

"A fascinating and eclectic collection! In Night Running, eleven essayists express, with bracing honesty, how a simple act of will—running in the dark—can free body and mind from fear, and restore the spirit."

-Novelist Mary Volmer, author of Crown of Dust and Reliance, Illinois

"Good writing, like a good run, should feel effortless even when ambitious. This collection of essays finds its stride early as it illuminates, entertains and often dazzles."

-Daniel Brown, author of The Big 50: San Francisco Giants: The Men and Moments That Made the San Francisco Giants

Notă biografică

Emily Mitchell, author of the novel The Last Summer of the World and, most recently, Viral: Stories, teaches at the University of Maryland and lives in Washington, D.C.

Joy Russo-Schoenfield, a former writer and editor at the Palm Beach Post, Newsday and CBS Sportsline.com, oversees Olympics and international sports coverage for ESPN digital and print media. She lives in Burlington, Connecticut.

Anne Milligan, an employment lawyer in Portland, Oregon, has represented clients in eight federal districts and before the Bureau of Labor and Industries. She is a former writer and content manager for Run Oregon.

Pete Danko reports on renewable energy and local business in Portland, Oregon, and is a wine-industry marketing and public relations consultant. His work has appeared in publications including the San Francisco Chronicle and the New York Times.

The nomadic Vanessa Runs, who roams the land in an RV, is a self-described “author, trail nerd, elevation junkie and mountain-loving dirtbag.” Her books include Daughters of Distance and The Summit Seeker.

Steve Kettmann, a former columnist for the Berliner Zeitung, is the author most recently of Baseball Maverick: How Sandy Alderson Revolutionized Baseball and Revived the Mets. He lives in Soquel, California.

Dahlia Scheindlin, an international public opinion researcher and political strategist, has consulted on campaigns in more than a dozen countries. She was raised in New York City and currently resides in Israel.

Heather Semb, a former resident intern at the Wellstone Center in the Redwoods writers’ retreat center in Northern California, is preparing to hike the Pacific Crest Trail. This is her first published essay.

T.J. Quinn, a former Chicago White Sox and New York Mets beat writer, is an investigative reporter for ESPN. He lives in New Jersey.

Former Wellstone Books intern Kelsey Eiland, a recent graduate of the University of California at Santa Cruz, works at the UCSC Arboretum and hopes to pursue a career in teaching.

Bonnie D. Ford, a former sports features writer for the Chicago Tribune and Cleveland Plain Dealer, is an enterprise and investigative reporter for ESPN.com. She splits her time between suburban Philadelphia and rural Maryland.

Joy Russo-Schoenfield, a former writer and editor at the Palm Beach Post, Newsday and CBS Sportsline.com, oversees Olympics and international sports coverage for ESPN digital and print media. She lives in Burlington, Connecticut.

Anne Milligan, an employment lawyer in Portland, Oregon, has represented clients in eight federal districts and before the Bureau of Labor and Industries. She is a former writer and content manager for Run Oregon.

Pete Danko reports on renewable energy and local business in Portland, Oregon, and is a wine-industry marketing and public relations consultant. His work has appeared in publications including the San Francisco Chronicle and the New York Times.

The nomadic Vanessa Runs, who roams the land in an RV, is a self-described “author, trail nerd, elevation junkie and mountain-loving dirtbag.” Her books include Daughters of Distance and The Summit Seeker.

Steve Kettmann, a former columnist for the Berliner Zeitung, is the author most recently of Baseball Maverick: How Sandy Alderson Revolutionized Baseball and Revived the Mets. He lives in Soquel, California.

Dahlia Scheindlin, an international public opinion researcher and political strategist, has consulted on campaigns in more than a dozen countries. She was raised in New York City and currently resides in Israel.

Heather Semb, a former resident intern at the Wellstone Center in the Redwoods writers’ retreat center in Northern California, is preparing to hike the Pacific Crest Trail. This is her first published essay.

T.J. Quinn, a former Chicago White Sox and New York Mets beat writer, is an investigative reporter for ESPN. He lives in New Jersey.

Former Wellstone Books intern Kelsey Eiland, a recent graduate of the University of California at Santa Cruz, works at the UCSC Arboretum and hopes to pursue a career in teaching.

Bonnie D. Ford, a former sports features writer for the Chicago Tribune and Cleveland Plain Dealer, is an enterprise and investigative reporter for ESPN.com. She splits her time between suburban Philadelphia and rural Maryland.

Extras

From 5

THE LAND OF THE

MIDNIGHT SUN

BY VANESSA RUNS

I have a dream of someday running the full length of the Alaska Highway, which winds from British Columbia, through the Yukon, and finally into Alaska, a challenge more commonly tackled by bikers or cyclists. The highway is the most beautiful I have ever seen, with a side of danger that gives me goose bumps. Moose outnumber people two to one in the Yukon. Traffic jams are caused by wildlife, not cars. Close to 80 percent of the territory remains pristine wilderness.

Alaska is home to thirty-thousand grizzlies, more than twenty times the number in the Lower 48. Scary as that sounds, I’m told a moose attack is statistically more likely – but in Haines, Alaska, I fed a moose a banana and kissed her on the nose. So there. Bear, moose, sheep and bison sightings are frequent on the highway. In a span of two hours of driving, we managed to see: fifty bison, twenty-five sheep, two moose, a caribou and a bear. Humans are out of place here, awkwardly weaving an asphalt path through the forest.

Yes, I want to run the highway, all 1,387 miles of it. Running the highway would guarantee face-to-face wildlife encounters, just the sort of adrenaline-fired jolt I look for in running. Some people run to lose weight, or to cross achievements off a list, or to clear their mind – and those are all worthy motivations. For me it is fear that drives me to run. Night running is the only activity I do where I can consistently take on and overcome my fears. It doesn’t matter how long I’ve been running or how experienced I’ve become, there will always be something new to scare me. I might be startled by an unexpected meeting with a wild animal or unnerved by a steep and rocky descent. Running at night invites the crazy, someday notion of running the Alaska Highway.

* * * * *

In At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past, Roger Ekirch laments that nighttime has become the forgotten half of human experience. There used to be a time when the cover of darkness liberated people. Social conventions took a backseat to primal impulses and the unapologetic pursuit of pleasure. Through running, I know that freedom. At night, I am no longer a trespasser picking my way through the trail. I become part of its ecosystem, just another animal in the wild. Sharpened senses and enlarged pupils guide my path. Hunting down my competition, I am a force to be reckoned with. Although these moments of euphoria are worth the physical exertion, the lows can also feel overwhelming.

It wasn’t anything as exotic as the Yukon or Alaska and there were no grizzlies to fear (or moose to feed), but on my thirty-first birthday, I decided to try a nighttime running experience with a different twist. I set off to do a self-supported birthday run on the beautiful Wildwood Trail in Forest Park in Portland, Oregon. The tradition among ultramarathon trail runners is to run one mile for every year on your birthday – thirty-one miles for me. Instead, I opted for the lofty goal of running one hour for every year, a whopping thirty-one hours of nonstop running. I had borrowed the idea from Catra Corbett, the tattooed ultrarunning superstar mentioned in Christopher McDougall’s famous book, Born to Run. At the Ridgecrest 50K in California, Catra helped me through a slump by passing me, then calling for me to follow her. I did, and she paced me to the finish. That got me to my first age-group ultramarathon win. On a birthday of her own, Catra ran for a mind-blowing forty-nine hours.

I went into the Wildwood challenge feeling confident. I had run thirty-one hours before on more challenging terrain, so I knew I had it in me. But my birthday, in late May, happened to fall on a rainy week in Portland, and it poured the entire time I was on the trail. The path became so muddy that my run turned into more of a controlled fall, testing my balance with every step. I couldn’t get into my comfortable and familiar long-distance running groove.

After running forty miles in these conditions, it grew dark. My feet were waterlogged and sloshing in my shoes. I had developed all sorts of new blisters under these wet conditions. My muscles were shot from trying to stay upright. But ultimately, it wasn’t the mud that got to me. It was nighttime. It was the darkness.

Running an organized race, you have aid stations. Every few miles you can see a light in the distance and know you can make it there. You have pacers. There is food and warmth and blankets along the way, places to dry off and people to hand you a hot chocolate. All I had now was a deep midnight before me, and I was horrified by how quickly it swallowed me up in a sense of despair.

What the hell am I doing out here all by myself? I wondered. The senselessness of my goal confronted me with every footfall. I was jumping at every noise and flinching at every corner, slowly allowing my fears to consume my thoughts and stir my imagination.

In my exhaustion, I bent over and laid a hand on the ground. The dark mud oozed through my fingers and under my nails. I saw that the mud had also covered the backs of my legs; streaks of dirty rain and grit dribbled down my calves. The wind whipped through the trees beside me, lashing them around like they were weightless and threatening to toss me farther down the trail. It poured and poured. I wanted to join the sky with my own tears, and at that moment I knew that night had won.

When I’m scared, I find myself turning to my past experiences of overcoming fear. The most scared I have ever been on a trail run was at the Grand Canyon’s Rim to Rim to Rim challenge. In one day, a group of us ran from the South Rim to the North Rim, and back again, a distance just shy of fifty miles. At first, it was glorious. I saw the sunrise over the rocks, the patient mules trudging down the trail, and the orange sand dusting my shoes. I bounded along like a carefree deer, thrilled to my core and grateful beyond words. Then, on the final climb up Bright Angel Trail – with seven miles to go – darkness fell. The animals started to come out, and I spotted the glowing eyes and outline of a mountain lion for the first time in my life. Bugs buzzed around my headlamp, attracted to its bright beam, and this attracted the bats. For miles, hungry bats would swoop down inches from my face to catch their dinner.

When I sat down to take a break, I realized that the ground was swarming with dozens of tiny scorpions. Whenever I stopped, they rushed toward me. I crawled out of that canyon exhausted and grateful to be alive. My nerves were shot.

* * * * *

I did get a big dose of Alaska fear on our visit, not on the highway, but on the Mount Marathon Race course in Seward. The race itself is not a marathon distance. It’s an infamous 5K from the edge of town to the top of 3,022-foot Mount Marathon and back that takes place every Fourth of July. To say this course is mountainous is an understatement. Essentially, it is a cliff.

Every year, four-hundred men, four-hundred women and two-hundred juniors line up for the grueling summit and descent. The average speed uphill is 2 mph. It’s more like bouldering than running. Downhill, speeds average 12 mph. Paramedics wait below to receive the bloodied and banged up finishers. Emergency crews are also positioned mid-summit to pull off the runners in severe distress. In 2012, a Mount Marathon runner from Anchorage disappeared on the course. He just … disappeared.

As crazy as this race sounds, my genius mind came up with the idea of doing it alone since we had missed the race date. This is how I found myself clinging for dear life off the side of a cliff with nobody around to hear my screams. Flies swarmed my bare arms and legs, tearing off mouthfuls of my skin and feasting happily by the hundreds. With all my limbs clinging to the cliff, I had no way of swatting the flies and frankly they were the least of my worries. In my desperation, I started to pray, repeating just four simple words, “Don’t let me die.” When I finally got to the bottom, I didn’t care that I hadn’t finished the complete course. I ran back to the RV and sighed deeply. I knew I had been stupid and risked too much.

I read articles about night running safety, and realize I am doing everything wrong. For example, I don’t always run with a buddy and I don’t run under bright streetlights. I seek out the deepest, darkest corners where the monsters live, and that’s where I go. Still, the risks are calculated and I’m usually willing to live with the worst that could happen. Even stronger than my fear of an attack is my fear of staying indoors. I don’t want things to be easier.

This is the drive that helped me complete three one-hundred-mile races – a distance I strongly associate with night running – in one year. And make no mistake: Running through the night is the hundred-miler. It sets these races apart from any other. In a fifty-miler or a 100K, you can finish and sleep in your own bed that night. In the hundred, there is no rest. You are forced to face your monsters head on, and they come out in the dark.

Nighttime for me usually comes at mile sixtieish. I have already been on my feet since sunrise and I am looking at a long night of running ahead. If I am lucky, I will finish shortly after the sun rises the next day. If I struggle, I will swelter in the heat and hope to finish before the afternoon sun burns off the last of my will. It’s an experience for which you can’t completely train. It’s also tough to mentally prepare for, because the iron-like mind you begin with turns to mush at mile fifty, sixty or seventy when the darkness hits and your nightmares come alive. It’s hard to prepare for the mind games, the sleep deprivation, the hallucinations.

In Greek mythology, Nyx is the goddess of the night. She is said to possess exceptional power and beauty, yet she has only ever been seen in glimpses. Her daughters are known as the Maniae. They are a group of spirits that personify insanity, madness and crazed frenzy. For the ultrarunner, night running and madness do indeed go hand in hand, one giving birth to the other. The hallucinations are the worst. They hit you at the peak of exhaustion and sleep deprivation. Although afterward you can laugh about them, when they are happening they’re a nightmare you can’t wake up from. In my first hundred-mile race I saw terrifying scarecrows and at one point I nearly cried, convinced that an enormous rattlesnake was on the path. There was nothing there.

When finishers talk about completing a hundred-miler, sometimes they say that they finished strong. Many of them have a good first fifty miles. But I have never heard anyone say, “Man, I rocked that night section!” On the contrary, runners talk about getting a second wind when the sun comes up. They talk about hanging on through the night. They remember wishing hard for the sun to rise or telling themselves if they can only get through the night, they might pull off a finish. But there are lessons. ...