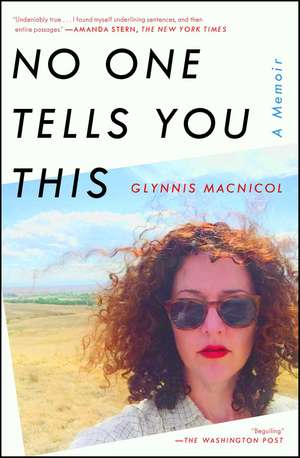

No One Tells You This: A Memoir

Autor Glynnis MacNicolen Limba Engleză Paperback – 24 iul 2019

If the story doesn’t end with marriage or a child, what then? This question plagued Glynnis MacNicol on the eve of her fortieth birthday. Despite a successful career as a writer, and an exciting life in New York City, Glynnis was constantly reminded she had neither of the things the world expected of a woman her age: a partner or a baby. She knew she was supposed to feel bad about this. After all, single women and those without children are often seen as objects of pity or indulgent spoiled creatures who think only of themselves. Glynnis refused to be cast into either of those roles, and yet the question remained: What now? There was no good blueprint for how to be a woman alone in the world. It was time to create one.

Over the course of her fortieth year, which this “beguiling” (The Washington Post) memoir chronicles, Glynnis embarks on a revealing journey of self-discovery that continually contradicts everything she’d been led to expect. Through the trials of family illness and turmoil, and the thrills of far-flung travel and adventures with men, young and old (and sometimes wearing cowboy hats), she wrestles with her biggest hopes and fears about love, death, sex, friendship, and loneliness. In doing so, she discovers that holding the power to determine her own fate requires a resilience and courage that no one talks about, and is more rewarding than anyone imagines.

“Amid the raft of motherhood memoirs out this summer, it’s refreshing to read a book unapologetically dedicated to the fulfillment of single life” (Vogue). No One Tells You This is an “honest” (Huffington Post) reckoning with modern womanhood and “a perfect balance between edgy and poignant” (People)—an exhilarating journey that will resonate with anyone determined to live by their own rules.

Preț: 98.56 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 148

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.86€ • 20.57$ • 15.90£

18.86€ • 20.57$ • 15.90£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 03-17 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781501163142

ISBN-10: 1501163140

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

ISBN-10: 1501163140

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

Notă biografică

Glynnis MacNicol is a writer and cofounder of The Li.st. Her work has appeared in print and online for publications including Elle.com (where she was a contributing writer), The New York Times, The Guardian, Forbes, The Cut, Daily News (New York), W, Town & Country, The Daily Beast, mental_floss, and Capital New York. Her series of articles on the Brownsville neighborhood in Brooklyn for Chase’s award-winning “From the Ground Up” package won a 2015 Contently Award. She is the author of the memoir No One Tells You This and the coauthor of There Will Be Blood, a guide to puberty, with HelloFlo founder Naama Bloom. She lives in New York City.

Extras

No One Tells You This

Eight hours before my fortieth birthday, I sat alone at my desk on the seventeenth floor of an office building in downtown Manhattan, unable to shake the conviction that midnight was hanging over me like a guillotine. I was certain that come the stroke of twelve my life would be cleaved in two, a before and an after: all that was good and interesting about me, that made me a person worthy of attention, considered by the world to be full of potential, would be stripped away, and whatever remained would be thrust, unrecognizable, into the void that awaited.

It was ridiculous. Deep down, I knew it was ridiculous. However, knowing this did not keep me from anxiously glancing at the clock out in the hallway as if the hands on it were actual blades.

I thought of my mother, of course. Whether or not we actually resemble the image we see, our mothers are our first, and most lasting, reflection of ourselves: a mirror we gaze into from birth until death.

I was eight when my mother turned forty, and while I could no longer recall the exact details of that day, I did have a vague memory of it being surrounded by the sort of manic hysteria I associated with the Cathy cartoons that were sometimes clipped and taped to our fridge. My mother loved the comics; she found joy in their simple, two-dimensional humor. For most of her life she would try to hand the comic strip section of the newspaper to me over the breakfast table or read them aloud, so I could enjoy them too. I never did. I was baffled that anyone found them interesting; they were so bloodless. At age eight, the appeal of the Cathy cartoon, about a single woman with heavy thighs, who dimly battled with her weight, her dating life, and her job, all with pathetic aplomb, was especially confusing. My interest in those days was almost exclusively directed at Princess Leia and Laura Ingalls. This sad Cathy creature, so often pictured feverishly trying to shove herself into bathing suits in department store changing rooms, struck me as the exact version of life I would happily expend all my future energy avoiding. Which is largely what I did.

My strongest impression of my mother’s birthday, however, was that it was an ending. I sensed an abandon all hope, ye who enter here message woven into the colorful birthday cards that arrived in the mail for her. As if simply by turning forty, my mother had somehow failed at something. And now here I was so many years later, about to turn forty myself, gripped by those identical fears despite all my determination to be otherwise. Eight-year-old me would have been revolted.

My desk faced north. Through the wall of windows that made up half of the corner office I was in, I had a panoramic view of the island. Below me Manhattan stretched out like a toy city, all sharp angles, silver rectangles, and the unbroken lines of the avenues running north. Even from this height the city exuded purpose, like an engine exhaust. Right then it was shimmering in the late afternoon, early September sun. The light cast a golden hue on everything. It was the sort of light that caused even the most hell-bent New Yorker to look up with renewed awe. I pulled out my phone, automatically angled my head in a well-practiced tilt, and took a selfie. I contemplated the result with some satisfaction, but I didn’t need the picture evidence. I was aware that to the outside world I could not have appeared less like a woman who should be worried about her age, less like someone who was now spending the last hours before her birthday seized by the belief she was being marched to her demise. In all likelihood, even my friends would have been surprised to hear it. I was not known as a person who tended to cower; I was a person who kept going, who took care of things, who always had the answer, who rarely asked for help. I had been on my own since I was eighteen years old. I had taken myself from waitress to well-paid writer to business owner and now back to writer without stopping to consider whether any of these things were plausible to anyone but me. I knew what I wanted, and what I liked, which was probably why most of my friends had taken me at my word when I said I didn’t want a birthday party; they were accustomed to me knowing my own mind. I wasn’t so sure anymore, however.

Currently my mind felt split, as though there were two voices in my head debating the importance of my birthday, and like the pendulum on a grandfather clock I was swinging from one to the other. The rational voice kept pointing out that it was not only shameful, but also a waste of time, to cower before age. Wouldn’t my energies be better spent contemplating how lucky I was? Lucky was too weak a word. Did I really need reminding that by nearly every metric available, there had never been a better time in history to be a woman? (Sometimes this voice merely noted how universally horrific it had been to be a woman up until very recently.) After all, I hadn’t been raised by a mother who responded to fifth grade homework questions, like “How many wives did Henry VIII have?” with a detailed explanation of the War of the Roses, only to arrive at this point in my life without a deeply ingrained sense of the larger picture.

Who cares, said the other voice. Sure, fine, technically it might be true I was lucky. But this so-called luck was no more interesting to me than the meals I’d been commanded to finish as a child because “there are starving children in the world”: knowing I was fortunate did not make the plate before me any more palatable. The only truth this increasingly feverish voice recognized was the sort that had been gleaned from stacks of literature, countless movies, and decades of magazine purchases I’d made: it was a truth universally acknowledged that by age forty I was supposed to have a certain kind of life, one that, whatever else it might involve, included a partner and babies. Having acquired neither of these, it was nearly impossible, no matter how smart, educated, or lucky I was, not to conclude that I had officially become the wrong answer to the question of what made a woman’s life worth living. If this story wasn’t going to end with a marriage or a child, what then? Could it even be called a story?

I very much wanted to muster a good fuck you to these voices. I reminded myself what the manager of the Greenwich Village tavern where I worked in my twenties as a waitress had once said to me (after listening to me lament my upcoming twenty-fifth birthday, no less): “You’ll never be younger than you are today.” But instead I laid my head on my desk and closed my eyes. Bring on the blade, I thought. I was so tired of my own mind it would be a relief.

My phone vibrated beside me and my heart leapt from long habit, like a dog that believes every noise of a package being opened holds the promise of food. But it was just my friend and now business partner, Rachel. Since leaving the office for a meeting a few hours ago, she had texted me some variation of PARTY? every fifteen minutes or so.

There’s still time! Party Party Party???? YES PARTY

Rachel had been offering to throw me a party all week. Her fortieth birthday party, two years prior, had taken place in a vast loft with a liquor sponsor. I had no doubt that if I’d wanted the same she would have managed to provide it, probably in the next two hours if I really made a fuss. She’d already put together a gift bag for me from twenty friends.

No Party, I wrote back.

She wasn’t the only one. People had asked and offered. There were a half dozen friends I could text right now, who would meet me at any place I chose. Whatever else it was, my birthday was not the story of a lonely woman. But I did not want a party. I couldn’t shake the feeling that the years ahead, if they were to be lived in a way that didn’t leave me feeling like I was standing in a corner watching the action but never living it, would require me to transform into a person I could not yet recognize and was not totally convinced even existed. A party felt like a delay tactic. A distraction. A weakness. If it was true that I was likely going to be alone for the rest of my life, let’s see how alone I could be.

This little spark of defiance had brought me comfort in recent days, but now I could barely strike it before it faded away. Not even the view could save me this time, it seemed. Right now, all it revealed was who I had been. I needed only to glance out the window to see my own history laid out before me. Live in the same place long enough and it eventually becomes a map to all your past lives: a different you waiting around every corner. And there had been plenty of versions of New York City me. From this vantage, I could practically trace my path beginning with my first heady year here, when I’d stumble out of after-hours clubs at 9:00 a.m. and be forced to walk home in the too-bright sun, having spent all the money I’d made the night before. The diner, somehow still in business, where Maddy and I would scrounge together our change and split $1.50 egg sandwiches. The shadowy ridge of midtown buildings, where I’d had my first office job in publishing, at age thirty-one, after deciding it was time to get my professional act together. The subway stop that I had walked through every day for six months, hoping to “accidentally” bump into the man who’d told me the “timing just wasn’t right.” And down there, too, was the office in SoHo where, after leaving publishing, I’d begun my mad charge up the media career ladder until it all came crashing down a few years later, shortly before I turned thirty-seven. Sitting here now thinking of those years, it occurred to me this birthday panic might not actually be such a recent development. If I was honest with myself it was probably truer to say I’d been turning forty for the past three years.

•

If someone had drawn a cartoon of me at age thirty-seven there would have been two equally sized thought bubbles over my head. Instead of words the first bubble would have contained an equation representing the sad reality that nearly everything in my life had become a shifting math problem with an immutable result: a baby. The calculation went something like this: I had x amount of activities in a week. If I met someone at one of them, how long would we have to get to know each other—a year seemed reasonable—before we’d need to be married so that it would leave enough time—six months perhaps?—to get pregnant before the cutoff (the cutoff being forty, the year in which a baby ceases to be a mathematical certainty and becomes a lucky roll of the dice). (Babies are never mathematical certainties, obviously, but that is one of those truths that is never true for you until it is true for you.) As thirty-seven became thirty-eight became thirty-nine the calculations became even more pressing and less feasible. Married next week, and pregnant the next morning? Time ticked on. Eventually there was no way to make the numbers add up. I couldn’t outrun my own clock.

The second bubble would simply have been a picture of me getting on a plane on short notice and leaving. By the time I turned thirty-seven, I was almost as consumed with the idea of getting away as I was with the conviction I was running out of time. Not traveling per se, just leaving. I was a media reporter in New York then, and I started my long work days from home. To the outside observer my job was glamorous: television appearances and glitzy parties. The reality was that it required me to chase website traffic like a shady lawyer going after an ambulance—clicks, no matter how ill-gotten, were the coin of the realm. Increasingly, early mornings had found me sitting at my desk in my tiny, sun-filled studio apartment (“It’s exactly the sort of apartment you dream of living in when you dream of living in New York,” my friend John said when he first saw it) where I paid twice as much rent as I’d ever paid in my life, listening to the garbage truck heave its way down the leafy streets of Brooklyn Heights, and wishing with every molecule of my being that I was the trash collector hanging off the back of it. All I could think as I gazed at it was: There is no internet on that garbage truck. Hunched over my desk, my BlackBerry buzzing like a trapped fly against a window, chat windows exploding on my screen with the urgency of dispatches being sent from a war zone, I spent months nearly paralyzed by my desire to be anywhere else.

That these two visions of my life were in direct contradiction with each other never once occurred to me. Not even a little bit. Neither did the fact that I wasn’t actually doing anything to make either outcome a reality. If anything, I was doing the opposite. When I wasn’t dating wildly inappropriate men, with whom there was little to no chance of building anything resembling a stable long-term relationship, I was working eighteen-hour days, nearly every day. Had I ever stopped long enough to consider things, I might have recognized the truth, which was that I’d never bothered to seriously question whether I actually wanted to be married with kids, or even just with kids (I’d at least Googled airplane ticket prices). I had simply taken it as a given, like financial security and regular exercise, obvious outcomes sane people generally aimed their lives toward. This lack of self-awareness was especially galling considering the singular focus with which I’d pursued other goals in my life. On paper at least, I was, by the time I turned thirty-seven, precisely where I had always wanted to be. I was a New Yorker; I was a full-time writer. Not just that. I was a full-time writer making a six-figure salary, plus excellent benefits, regularly appearing on TV to talk about subjects I’d written on. It was a position I had achieved less than five years after waiting my last table.

It hadn’t come easily. I had worked for it, relentlessly. For most of my thirties, I’d been on fire with determination. I’d been a pyre of ambition, fueled by what I considered all the lost time of my twenties. Which worked out admirably well, until I also went up in smoke. Or so it felt like to me. Life on the internet, the very thing that had allowed me to skip over the years of drudgery I knew had been required of nearly every established writer I’d admired, eventually caught up to me. There are no speed bumps in the digital world. No clocking out. No off switch. It was as though my career was a car racing across an endless plain, on a road with no speed limits, pedal to the floor: the only thing that was going to stop me was me. And that was exactly what happened. Five years into my career, at the top of my game, I didn’t so much stop as buckle under my own momentum. The fiery ambition that had once driven me to work eighteen hours a day, seven days a week, for years, consumed me until I burned up. Burned out.

Burned out. Another weak phrase—as if borrowed from a subway advertisement for bubble bath or resort vacations—to describe something that felt so shattering. It had started slowly and the early warning signs were easy to ignore. When I started thinking of writing as punishment instead of fortune, for instance, people said it was just the subject matter, I should switch beats. When I started approaching my workday with dread instead of eagerness, people told me I just needed a vacation. But it turned out this was like telling someone whose house has been destroyed in a natural disaster that they simply needed a fresh coat of paint. The hours I’d been clocking for years on end had pushed me past the point of quick fixes—past the point of caring about finding a fix, it turned out. I simply went through my day on autopilot, resentful but too worn out to make any changes. Then, three months after my thirty-seventh birthday, I was called into a meeting with the company’s manager, where it was gently but firmly suggested I figure out how to get a better attitude, or else (the or else was not said out loud, but the implication was impossible to miss). Without thinking, I opened my mouth to promise I would try harder (in this instance, rational me was thinking about salary and health benefits and the fact I’d just been quoted in a full page ad in the New York Times), but instead what came out was “I’m done.” I was given the weekend to think it over, but I didn’t need to; some fundamental part of me had taken the wheel and was pulling me off the road. Instead, I cleared my desk out and walked home over the Brooklyn Bridge feeling giddy with my new freedom. This sensation lasted for a few weeks, buoyed along by plenty of good for yous! and I wish I could do that. I’ve noticed it’s almost always people who are living the exact opposite lives than you, and facing none of the risks, who are most encouraging. Eventually the rush wore off and reality began to set in, and yet I found myself unable to stop doing nothing. Panic, my reliable companion, the thing that had kicked me into gear at other times in my life when I’d veered too close to the cliff’s edge, was nowhere to be found. I knew I should be panicked, but try as I might I couldn’t muster it. I felt like I’d had a lobotomy. (Later a therapist would tell me this was not my imagination, that true burnout left one “numb,” operating in “survival mode,” though the latter phrase again struck me as absurd, considering actual survival had seemingly ceased to be a concern to me during this time.)

During those months of doing nothing, I watched the numbers in my savings account disappear, as though observing a weather report from a far-off land. When I thought about it at all, I sometimes considered how differently I’d be behaving if, for instance, I had a child to support. Presumably the necessity of a paycheck to keep someone else alive might have eclipsed the manner in which I earned it. Other days I wondered what it would be like not to be in this alone, to know there was someone else to pick up the financial slack. (I sometimes regarded my married friends who had health benefits thanks to their husbands’ jobs with the same envious and irrational gaze I’d formerly laid on the garbage truck drivers.) Perhaps this imagined partner might say something like: “You’ve worked hard enough, honey, I’ll cover the rent this month,” or “Take the time you need, your happiness is important, I’ve got this.” But I was alone—my parents had never been a source of financial support, and thirty-seven-year-old employable women did not go to friends, who themselves now had families to think about, and ask for loans. Instead I did nothing. In fact, my only source of enjoyment during those bleak months was telling people I did nothing. (Nothing stops New York cocktail party conversation quite as abruptly as the phrase I do nothing.) I felt like I was playing chicken with myself. I could see the cliff’s edge—would I drive myself off? How close could I get? Did it matter? I was the only person relying on me, and I did not seem to care what happened.

It took a gutted bank account (something I’d never allowed to happen before) and, until my cable and internet were cut off for nonpayment, many afternoons of watching Golden Girls reruns (the envy I felt toward fictional retired women living in Florida before the internet was unlike any I’d experienced—I wanted to crawl into my TV screen Poltergeist-style) before I really hit rock bottom and began piecing my professional life back together. It had taken two years, but I was now approaching solid ground.

•

I returned my gaze to the city skyline. It was precisely the sort of view that belonged to a “master of the universe” character in a Tom Wolfe novel. Which was fitting, I supposed—I was now, if nothing else, master of my own universe, self-made, my own boss. From this office, Rachel and I ran our small, newly sustainable networking business—the old boys’ club for women, we called it. Our partnership had been conceived of in the black center of my burnout; it was a pinpoint of light I could walk toward, and more practically speaking, something to do that might keep me from looming eviction. After much trial and error, we’d made it work. In addition to this, I was slowly but surely reassembling my freelance writing career in a way that made me want to come to the computer instead of flee from it. I could once again pay my rent. And yet, despite all this, here I was still feeling unsteady.

The city gazed back at me in all its triumphant, unapologetic power. The city did not care that I was determined to ignore my birthday. It would quite happily ignore my birthday right along with me if I so chose. It was my job to convince the city I was worth paying attention to at all. It was now five o’clock. Was I really going to go home? Sad, sad Glynnis retreating to her studio apartment, defeated by her age. This could not be the story of my birthday. More than anything, it was just too boring. In an effort to avoid appearing pathetic, it was starting to occur to me that I was being very pathetic. At the very least I’d take myself out for a drink at the Bemelmans Bar, the Upper East Side institution on the ground floor of the Carlyle Hotel. The walls of Bemelmans were illustrated by its namesake, Ludwig Bemelmans, author of the Madeline children’s books, who had stayed as a guest there for many months. It was as old-school as it was possible to get in New York, and if the city was my sanctuary, Bemelmans was my sanctuary within it in my lowest moments.

Newly fired up by my plan, I opened my computer and looked up hotel room rates at the Carlyle. I could pack a pair of silk pajamas, have a martini at Bemelmans, and wake up to a stroll in Central Park.

Good Lord.

I closed the tab almost as quickly as I’d opened it. Not even the most acrobatic, panicked, you-only-turn-forty-once rationalizations could justify half a month’s (already obscenely high) rent on one night in a hotel. I might not know what sort of life awaited me, but I was certain whatever shape it took I would still have to pay my bills. Even so, I’d hit on the missing piece. I was desperate to be in motion. To have a destination on a day that was leaving me feeling paralyzed and without purpose. It was too late for a road trip now, though I suddenly understood clearly that’s what I should have done. I thought of all the motels I’d stayed in over the years on various cross-country road trips. The promise of their glowing neon signs, the rooms’ brief answers to the quintessential question of the road: where to next? That’s what I needed.

I turned over the city in my head. Most of the hotels were in Times Square and full of tourists. I had never been a tourist, and I wasn’t about to start now. Suddenly I recalled the newly opened motel out in the Rockaways I’d heard people talking about over the summer. The Rockaways were technically a part of Queens, a little peninsula that jutted out into the water southeast of Coney Island and lined on all sides with beaches. The area had been a summer destination for city dwellers looking to escape the heat since the mid-nineteenth century, and had come in and out of fashion ever since. The neighborhood had the feel of a beach town even though it was possible to see the city’s skyline in the distance. Another world inside the same city, only a subway ride away. It was one of New York’s better magic tricks. I Googled the hotel. It was open! A few more clicks and I had booked a seventy-five-dollar room. Just like that, I’d managed to tilt the world just enough to let it refill with some possibility. I packed my things and took one last look out the window. The sinking sun had tinged the silver buildings gold, giving me the sensation of being granted a glowing send-off.

1. The Forecast

Eight hours before my fortieth birthday, I sat alone at my desk on the seventeenth floor of an office building in downtown Manhattan, unable to shake the conviction that midnight was hanging over me like a guillotine. I was certain that come the stroke of twelve my life would be cleaved in two, a before and an after: all that was good and interesting about me, that made me a person worthy of attention, considered by the world to be full of potential, would be stripped away, and whatever remained would be thrust, unrecognizable, into the void that awaited.

It was ridiculous. Deep down, I knew it was ridiculous. However, knowing this did not keep me from anxiously glancing at the clock out in the hallway as if the hands on it were actual blades.

I thought of my mother, of course. Whether or not we actually resemble the image we see, our mothers are our first, and most lasting, reflection of ourselves: a mirror we gaze into from birth until death.

I was eight when my mother turned forty, and while I could no longer recall the exact details of that day, I did have a vague memory of it being surrounded by the sort of manic hysteria I associated with the Cathy cartoons that were sometimes clipped and taped to our fridge. My mother loved the comics; she found joy in their simple, two-dimensional humor. For most of her life she would try to hand the comic strip section of the newspaper to me over the breakfast table or read them aloud, so I could enjoy them too. I never did. I was baffled that anyone found them interesting; they were so bloodless. At age eight, the appeal of the Cathy cartoon, about a single woman with heavy thighs, who dimly battled with her weight, her dating life, and her job, all with pathetic aplomb, was especially confusing. My interest in those days was almost exclusively directed at Princess Leia and Laura Ingalls. This sad Cathy creature, so often pictured feverishly trying to shove herself into bathing suits in department store changing rooms, struck me as the exact version of life I would happily expend all my future energy avoiding. Which is largely what I did.

My strongest impression of my mother’s birthday, however, was that it was an ending. I sensed an abandon all hope, ye who enter here message woven into the colorful birthday cards that arrived in the mail for her. As if simply by turning forty, my mother had somehow failed at something. And now here I was so many years later, about to turn forty myself, gripped by those identical fears despite all my determination to be otherwise. Eight-year-old me would have been revolted.

My desk faced north. Through the wall of windows that made up half of the corner office I was in, I had a panoramic view of the island. Below me Manhattan stretched out like a toy city, all sharp angles, silver rectangles, and the unbroken lines of the avenues running north. Even from this height the city exuded purpose, like an engine exhaust. Right then it was shimmering in the late afternoon, early September sun. The light cast a golden hue on everything. It was the sort of light that caused even the most hell-bent New Yorker to look up with renewed awe. I pulled out my phone, automatically angled my head in a well-practiced tilt, and took a selfie. I contemplated the result with some satisfaction, but I didn’t need the picture evidence. I was aware that to the outside world I could not have appeared less like a woman who should be worried about her age, less like someone who was now spending the last hours before her birthday seized by the belief she was being marched to her demise. In all likelihood, even my friends would have been surprised to hear it. I was not known as a person who tended to cower; I was a person who kept going, who took care of things, who always had the answer, who rarely asked for help. I had been on my own since I was eighteen years old. I had taken myself from waitress to well-paid writer to business owner and now back to writer without stopping to consider whether any of these things were plausible to anyone but me. I knew what I wanted, and what I liked, which was probably why most of my friends had taken me at my word when I said I didn’t want a birthday party; they were accustomed to me knowing my own mind. I wasn’t so sure anymore, however.

Currently my mind felt split, as though there were two voices in my head debating the importance of my birthday, and like the pendulum on a grandfather clock I was swinging from one to the other. The rational voice kept pointing out that it was not only shameful, but also a waste of time, to cower before age. Wouldn’t my energies be better spent contemplating how lucky I was? Lucky was too weak a word. Did I really need reminding that by nearly every metric available, there had never been a better time in history to be a woman? (Sometimes this voice merely noted how universally horrific it had been to be a woman up until very recently.) After all, I hadn’t been raised by a mother who responded to fifth grade homework questions, like “How many wives did Henry VIII have?” with a detailed explanation of the War of the Roses, only to arrive at this point in my life without a deeply ingrained sense of the larger picture.

Who cares, said the other voice. Sure, fine, technically it might be true I was lucky. But this so-called luck was no more interesting to me than the meals I’d been commanded to finish as a child because “there are starving children in the world”: knowing I was fortunate did not make the plate before me any more palatable. The only truth this increasingly feverish voice recognized was the sort that had been gleaned from stacks of literature, countless movies, and decades of magazine purchases I’d made: it was a truth universally acknowledged that by age forty I was supposed to have a certain kind of life, one that, whatever else it might involve, included a partner and babies. Having acquired neither of these, it was nearly impossible, no matter how smart, educated, or lucky I was, not to conclude that I had officially become the wrong answer to the question of what made a woman’s life worth living. If this story wasn’t going to end with a marriage or a child, what then? Could it even be called a story?

I very much wanted to muster a good fuck you to these voices. I reminded myself what the manager of the Greenwich Village tavern where I worked in my twenties as a waitress had once said to me (after listening to me lament my upcoming twenty-fifth birthday, no less): “You’ll never be younger than you are today.” But instead I laid my head on my desk and closed my eyes. Bring on the blade, I thought. I was so tired of my own mind it would be a relief.

My phone vibrated beside me and my heart leapt from long habit, like a dog that believes every noise of a package being opened holds the promise of food. But it was just my friend and now business partner, Rachel. Since leaving the office for a meeting a few hours ago, she had texted me some variation of PARTY? every fifteen minutes or so.

There’s still time! Party Party Party???? YES PARTY

Rachel had been offering to throw me a party all week. Her fortieth birthday party, two years prior, had taken place in a vast loft with a liquor sponsor. I had no doubt that if I’d wanted the same she would have managed to provide it, probably in the next two hours if I really made a fuss. She’d already put together a gift bag for me from twenty friends.

No Party, I wrote back.

She wasn’t the only one. People had asked and offered. There were a half dozen friends I could text right now, who would meet me at any place I chose. Whatever else it was, my birthday was not the story of a lonely woman. But I did not want a party. I couldn’t shake the feeling that the years ahead, if they were to be lived in a way that didn’t leave me feeling like I was standing in a corner watching the action but never living it, would require me to transform into a person I could not yet recognize and was not totally convinced even existed. A party felt like a delay tactic. A distraction. A weakness. If it was true that I was likely going to be alone for the rest of my life, let’s see how alone I could be.

This little spark of defiance had brought me comfort in recent days, but now I could barely strike it before it faded away. Not even the view could save me this time, it seemed. Right now, all it revealed was who I had been. I needed only to glance out the window to see my own history laid out before me. Live in the same place long enough and it eventually becomes a map to all your past lives: a different you waiting around every corner. And there had been plenty of versions of New York City me. From this vantage, I could practically trace my path beginning with my first heady year here, when I’d stumble out of after-hours clubs at 9:00 a.m. and be forced to walk home in the too-bright sun, having spent all the money I’d made the night before. The diner, somehow still in business, where Maddy and I would scrounge together our change and split $1.50 egg sandwiches. The shadowy ridge of midtown buildings, where I’d had my first office job in publishing, at age thirty-one, after deciding it was time to get my professional act together. The subway stop that I had walked through every day for six months, hoping to “accidentally” bump into the man who’d told me the “timing just wasn’t right.” And down there, too, was the office in SoHo where, after leaving publishing, I’d begun my mad charge up the media career ladder until it all came crashing down a few years later, shortly before I turned thirty-seven. Sitting here now thinking of those years, it occurred to me this birthday panic might not actually be such a recent development. If I was honest with myself it was probably truer to say I’d been turning forty for the past three years.

•

If someone had drawn a cartoon of me at age thirty-seven there would have been two equally sized thought bubbles over my head. Instead of words the first bubble would have contained an equation representing the sad reality that nearly everything in my life had become a shifting math problem with an immutable result: a baby. The calculation went something like this: I had x amount of activities in a week. If I met someone at one of them, how long would we have to get to know each other—a year seemed reasonable—before we’d need to be married so that it would leave enough time—six months perhaps?—to get pregnant before the cutoff (the cutoff being forty, the year in which a baby ceases to be a mathematical certainty and becomes a lucky roll of the dice). (Babies are never mathematical certainties, obviously, but that is one of those truths that is never true for you until it is true for you.) As thirty-seven became thirty-eight became thirty-nine the calculations became even more pressing and less feasible. Married next week, and pregnant the next morning? Time ticked on. Eventually there was no way to make the numbers add up. I couldn’t outrun my own clock.

The second bubble would simply have been a picture of me getting on a plane on short notice and leaving. By the time I turned thirty-seven, I was almost as consumed with the idea of getting away as I was with the conviction I was running out of time. Not traveling per se, just leaving. I was a media reporter in New York then, and I started my long work days from home. To the outside observer my job was glamorous: television appearances and glitzy parties. The reality was that it required me to chase website traffic like a shady lawyer going after an ambulance—clicks, no matter how ill-gotten, were the coin of the realm. Increasingly, early mornings had found me sitting at my desk in my tiny, sun-filled studio apartment (“It’s exactly the sort of apartment you dream of living in when you dream of living in New York,” my friend John said when he first saw it) where I paid twice as much rent as I’d ever paid in my life, listening to the garbage truck heave its way down the leafy streets of Brooklyn Heights, and wishing with every molecule of my being that I was the trash collector hanging off the back of it. All I could think as I gazed at it was: There is no internet on that garbage truck. Hunched over my desk, my BlackBerry buzzing like a trapped fly against a window, chat windows exploding on my screen with the urgency of dispatches being sent from a war zone, I spent months nearly paralyzed by my desire to be anywhere else.

That these two visions of my life were in direct contradiction with each other never once occurred to me. Not even a little bit. Neither did the fact that I wasn’t actually doing anything to make either outcome a reality. If anything, I was doing the opposite. When I wasn’t dating wildly inappropriate men, with whom there was little to no chance of building anything resembling a stable long-term relationship, I was working eighteen-hour days, nearly every day. Had I ever stopped long enough to consider things, I might have recognized the truth, which was that I’d never bothered to seriously question whether I actually wanted to be married with kids, or even just with kids (I’d at least Googled airplane ticket prices). I had simply taken it as a given, like financial security and regular exercise, obvious outcomes sane people generally aimed their lives toward. This lack of self-awareness was especially galling considering the singular focus with which I’d pursued other goals in my life. On paper at least, I was, by the time I turned thirty-seven, precisely where I had always wanted to be. I was a New Yorker; I was a full-time writer. Not just that. I was a full-time writer making a six-figure salary, plus excellent benefits, regularly appearing on TV to talk about subjects I’d written on. It was a position I had achieved less than five years after waiting my last table.

It hadn’t come easily. I had worked for it, relentlessly. For most of my thirties, I’d been on fire with determination. I’d been a pyre of ambition, fueled by what I considered all the lost time of my twenties. Which worked out admirably well, until I also went up in smoke. Or so it felt like to me. Life on the internet, the very thing that had allowed me to skip over the years of drudgery I knew had been required of nearly every established writer I’d admired, eventually caught up to me. There are no speed bumps in the digital world. No clocking out. No off switch. It was as though my career was a car racing across an endless plain, on a road with no speed limits, pedal to the floor: the only thing that was going to stop me was me. And that was exactly what happened. Five years into my career, at the top of my game, I didn’t so much stop as buckle under my own momentum. The fiery ambition that had once driven me to work eighteen hours a day, seven days a week, for years, consumed me until I burned up. Burned out.

Burned out. Another weak phrase—as if borrowed from a subway advertisement for bubble bath or resort vacations—to describe something that felt so shattering. It had started slowly and the early warning signs were easy to ignore. When I started thinking of writing as punishment instead of fortune, for instance, people said it was just the subject matter, I should switch beats. When I started approaching my workday with dread instead of eagerness, people told me I just needed a vacation. But it turned out this was like telling someone whose house has been destroyed in a natural disaster that they simply needed a fresh coat of paint. The hours I’d been clocking for years on end had pushed me past the point of quick fixes—past the point of caring about finding a fix, it turned out. I simply went through my day on autopilot, resentful but too worn out to make any changes. Then, three months after my thirty-seventh birthday, I was called into a meeting with the company’s manager, where it was gently but firmly suggested I figure out how to get a better attitude, or else (the or else was not said out loud, but the implication was impossible to miss). Without thinking, I opened my mouth to promise I would try harder (in this instance, rational me was thinking about salary and health benefits and the fact I’d just been quoted in a full page ad in the New York Times), but instead what came out was “I’m done.” I was given the weekend to think it over, but I didn’t need to; some fundamental part of me had taken the wheel and was pulling me off the road. Instead, I cleared my desk out and walked home over the Brooklyn Bridge feeling giddy with my new freedom. This sensation lasted for a few weeks, buoyed along by plenty of good for yous! and I wish I could do that. I’ve noticed it’s almost always people who are living the exact opposite lives than you, and facing none of the risks, who are most encouraging. Eventually the rush wore off and reality began to set in, and yet I found myself unable to stop doing nothing. Panic, my reliable companion, the thing that had kicked me into gear at other times in my life when I’d veered too close to the cliff’s edge, was nowhere to be found. I knew I should be panicked, but try as I might I couldn’t muster it. I felt like I’d had a lobotomy. (Later a therapist would tell me this was not my imagination, that true burnout left one “numb,” operating in “survival mode,” though the latter phrase again struck me as absurd, considering actual survival had seemingly ceased to be a concern to me during this time.)

During those months of doing nothing, I watched the numbers in my savings account disappear, as though observing a weather report from a far-off land. When I thought about it at all, I sometimes considered how differently I’d be behaving if, for instance, I had a child to support. Presumably the necessity of a paycheck to keep someone else alive might have eclipsed the manner in which I earned it. Other days I wondered what it would be like not to be in this alone, to know there was someone else to pick up the financial slack. (I sometimes regarded my married friends who had health benefits thanks to their husbands’ jobs with the same envious and irrational gaze I’d formerly laid on the garbage truck drivers.) Perhaps this imagined partner might say something like: “You’ve worked hard enough, honey, I’ll cover the rent this month,” or “Take the time you need, your happiness is important, I’ve got this.” But I was alone—my parents had never been a source of financial support, and thirty-seven-year-old employable women did not go to friends, who themselves now had families to think about, and ask for loans. Instead I did nothing. In fact, my only source of enjoyment during those bleak months was telling people I did nothing. (Nothing stops New York cocktail party conversation quite as abruptly as the phrase I do nothing.) I felt like I was playing chicken with myself. I could see the cliff’s edge—would I drive myself off? How close could I get? Did it matter? I was the only person relying on me, and I did not seem to care what happened.

It took a gutted bank account (something I’d never allowed to happen before) and, until my cable and internet were cut off for nonpayment, many afternoons of watching Golden Girls reruns (the envy I felt toward fictional retired women living in Florida before the internet was unlike any I’d experienced—I wanted to crawl into my TV screen Poltergeist-style) before I really hit rock bottom and began piecing my professional life back together. It had taken two years, but I was now approaching solid ground.

•

I returned my gaze to the city skyline. It was precisely the sort of view that belonged to a “master of the universe” character in a Tom Wolfe novel. Which was fitting, I supposed—I was now, if nothing else, master of my own universe, self-made, my own boss. From this office, Rachel and I ran our small, newly sustainable networking business—the old boys’ club for women, we called it. Our partnership had been conceived of in the black center of my burnout; it was a pinpoint of light I could walk toward, and more practically speaking, something to do that might keep me from looming eviction. After much trial and error, we’d made it work. In addition to this, I was slowly but surely reassembling my freelance writing career in a way that made me want to come to the computer instead of flee from it. I could once again pay my rent. And yet, despite all this, here I was still feeling unsteady.

The city gazed back at me in all its triumphant, unapologetic power. The city did not care that I was determined to ignore my birthday. It would quite happily ignore my birthday right along with me if I so chose. It was my job to convince the city I was worth paying attention to at all. It was now five o’clock. Was I really going to go home? Sad, sad Glynnis retreating to her studio apartment, defeated by her age. This could not be the story of my birthday. More than anything, it was just too boring. In an effort to avoid appearing pathetic, it was starting to occur to me that I was being very pathetic. At the very least I’d take myself out for a drink at the Bemelmans Bar, the Upper East Side institution on the ground floor of the Carlyle Hotel. The walls of Bemelmans were illustrated by its namesake, Ludwig Bemelmans, author of the Madeline children’s books, who had stayed as a guest there for many months. It was as old-school as it was possible to get in New York, and if the city was my sanctuary, Bemelmans was my sanctuary within it in my lowest moments.

Newly fired up by my plan, I opened my computer and looked up hotel room rates at the Carlyle. I could pack a pair of silk pajamas, have a martini at Bemelmans, and wake up to a stroll in Central Park.

Good Lord.

I closed the tab almost as quickly as I’d opened it. Not even the most acrobatic, panicked, you-only-turn-forty-once rationalizations could justify half a month’s (already obscenely high) rent on one night in a hotel. I might not know what sort of life awaited me, but I was certain whatever shape it took I would still have to pay my bills. Even so, I’d hit on the missing piece. I was desperate to be in motion. To have a destination on a day that was leaving me feeling paralyzed and without purpose. It was too late for a road trip now, though I suddenly understood clearly that’s what I should have done. I thought of all the motels I’d stayed in over the years on various cross-country road trips. The promise of their glowing neon signs, the rooms’ brief answers to the quintessential question of the road: where to next? That’s what I needed.

I turned over the city in my head. Most of the hotels were in Times Square and full of tourists. I had never been a tourist, and I wasn’t about to start now. Suddenly I recalled the newly opened motel out in the Rockaways I’d heard people talking about over the summer. The Rockaways were technically a part of Queens, a little peninsula that jutted out into the water southeast of Coney Island and lined on all sides with beaches. The area had been a summer destination for city dwellers looking to escape the heat since the mid-nineteenth century, and had come in and out of fashion ever since. The neighborhood had the feel of a beach town even though it was possible to see the city’s skyline in the distance. Another world inside the same city, only a subway ride away. It was one of New York’s better magic tricks. I Googled the hotel. It was open! A few more clicks and I had booked a seventy-five-dollar room. Just like that, I’d managed to tilt the world just enough to let it refill with some possibility. I packed my things and took one last look out the window. The sinking sun had tinged the silver buildings gold, giving me the sensation of being granted a glowing send-off.

Descriere

No One Tells You This is a sharp, intimate, funny, frank and fearless memoir…and a refreshing view of the possibilities and pitfalls, personal freedom can offer modern women.

If the story doesn’t end with marriage or a child, what then? This question plagued Glynnis MacNicol on the eve of her fortieth birthday. Despite a successful career as a writer, and an exciting life in New York City, Glynnis was constantly reminded lacked two very important things: a partner or a baby. She knew she was supposed to feel bad about this. After all, single women and those without children are often seen as objects of pity or indulgent spoiled creatures who think only of themselves. Glynnis refused to be cast into either of those roles, and yet the question remained: What now? There was no good blueprint for how to be a woman alone in the world. It was time to create one.

Over the course of her fortieth year, which this memoir chronicles, Glynnis embarks on a revealing journey of self-discovery that continually contradicts everything she’d been led to expect. Through the trials of family illness and turmoil, and the thrills of far-flung travel and adventures with men, young and old (and sometimes wearing cowboy hats), she wrestles with her biggest hopes and fears about love, death, sex, friendship, and loneliness. In doing so, she discovers that holding the power to determine her own fate requires a resilience and courage that no one talks about, and is more rewarding than anyone imagines.

* Named one of TIME's Best Memoirs of 2018

* Glynnis MacNicol is the co-founder of TheLi.st, a network and visibility platform for professional women.

If the story doesn’t end with marriage or a child, what then? This question plagued Glynnis MacNicol on the eve of her fortieth birthday. Despite a successful career as a writer, and an exciting life in New York City, Glynnis was constantly reminded lacked two very important things: a partner or a baby. She knew she was supposed to feel bad about this. After all, single women and those without children are often seen as objects of pity or indulgent spoiled creatures who think only of themselves. Glynnis refused to be cast into either of those roles, and yet the question remained: What now? There was no good blueprint for how to be a woman alone in the world. It was time to create one.

Over the course of her fortieth year, which this memoir chronicles, Glynnis embarks on a revealing journey of self-discovery that continually contradicts everything she’d been led to expect. Through the trials of family illness and turmoil, and the thrills of far-flung travel and adventures with men, young and old (and sometimes wearing cowboy hats), she wrestles with her biggest hopes and fears about love, death, sex, friendship, and loneliness. In doing so, she discovers that holding the power to determine her own fate requires a resilience and courage that no one talks about, and is more rewarding than anyone imagines.

* Named one of TIME's Best Memoirs of 2018

* Glynnis MacNicol is the co-founder of TheLi.st, a network and visibility platform for professional women.