Nothing But a Smile: Abigail and John Adams

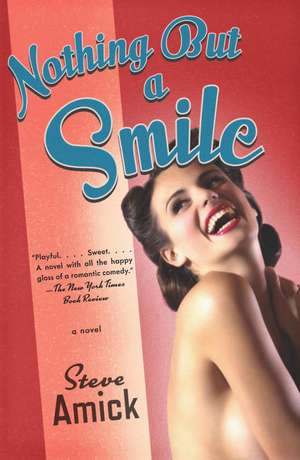

Autor Steve Amicken Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2010

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Michigan Notable Books (2010)

It's 1944, and Wink Dutton, a former illustrator for Yank and Stars and Stripes, arrives in Chicago after an injury to his drawing hand gets him discharged. Renting a room above the camera shop run by Sal Chesterton—the wife of Wink's buddy, still stationed in the Philippines—Wink is surprised to learn how Sal is making ends meet: producing pinup photos for the soldiers' girlie magazines. In fact, she's using herself as a model. When Wink becomes a partner in her covert enterprise, it's the beginning of a collaboration that is both wonderfully sexy and pure, one that not only leads to Wink’s reinvention as a photographer but also—amid the painful adjustments of the postwar world—blossoms into a subtle and unexpected romance.

Preț: 132.57 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 199

Preț estimativ în valută:

25.37€ • 26.56$ • 20.99£

25.37€ • 26.56$ • 20.99£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307390196

ISBN-10: 0307390195

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 141 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0307390195

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 141 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Steve Amick is the author of The Lake, the River & the Other Lake. Born in Ann Arbor, Michigan, he received a BA from St. Lawrence University and an MFA in creative writing from George Mason University. His short stories have appeared in Playboy, The Southern Review, New England Review, Story, McSweeney’s, in the anthology The Sound of Writing, and on National Public Radio. On walks with his wife and young son, he often passes the original Argus Camera building.

Extras

1

On a warm June day in 1944, Wink Dutton, known most recently to the U.S. Army as Staff Sergeant Winton S. Dutton, special correspondent and burgeoning cartoonist and illustrator, stepped out onto the streets of Chicago in his civvies. In his pocket, he had seventeen dollars, the address of his buddy’s camera shop, a short list of publishers and advertising agencies, and the Purple Heart awarded to him for misunderstanding an ensign’s instructions regarding a flywheel aboard a sub he was supposed to be working up a piece on for the pages of Yank magazine.

The ensign had probably told him more than clearly to “Keep your finger out of this here,” but given the effects of a bottle of peach brandy the night before—a gift from a grateful quartermaster colonel for the boldly rugged rendering he’d done of him to accompany an article about fruitcake distribution and Christmas morale—the submarine tour seemed more like a cacophony of alarms, whistles, bells, and bellowing. He couldn’t think of a worse post-brandy story than, possibly, covering a riveter’s competition at a shipyard. Between the banging in his head and the banging in the tin can that was the USS _____________ (name censored for military secrecy), the only message he was able to receive was “Be sure to touch this flywheel I’m pointing to.”

He didn’t actually lose the hand, just proper use of the middle finger down to the pinky, plus the tip of the middle finger, right where he rested his pencils, pens, and paintbrushes.

“It’s the fuck finger and then some,” the navy doctor informed him. “You can still pinch, of course.”

“Great,” he’d told him. “I’ll put in for a transfer to the Pinching Brigade. I’ll get right on that.”

Before Wink shipped out of Townsville, Queensland, Sergeant Bill Chesterton, known to his fellow correspondents and poker players as Chesty, stopped by to say good-bye and good luck—and since Wink was planning on heading to Chicago, could he check in on his wife, Sal, and tell her he loved her still and was still being true?

“Absolutely,” he told him, and resisted horsing around with any cheap jokes—offering to do more than that for him or doubt the man’s statement of fidelity. It was the sort of thing guys did, the way they kidded, but personally, he thought it was a little too mean and a little too easy. And a little too close to the sort of demoralizing crap guys could hear plenty just by dialing in Tokyo Rose on the radio.

Besides, he counted himself lucky for having no such serious attachments—either back in the States or in the Pacific

theater—and it was only this luck, he knew, that kept him from being such a vulnerable, miserable, hang-faced slob.

He made four stabs at the job search that first day in Chicago. All three interviewers were respectful and very complimentary of his portfolio. The two that seemed at least on the ball enough to assess his new situation—that he wouldn’t be able to illustrate or cartoon anymore and that the third thing he did marginally well, writing copy, was also limited as he had yet to relearn how to write with the other hand, and it left his typing appallingly more hunt-and-peck—nevertheless agreed that he would still make a great art director. Unfortunately, neither one currently had any art director positions available. At one of the four stops, an ad agency that was doing a lot of promotional poster work for the bond drive, he was told they might be needing a new stock boy in the art department soon, but that wouldn’t happen for another month and only if the husband of the girl currently holding the job got shipped stateside, in which case they imagined she would most likely want to quit work and return to taking care of her home. It hardly sounded like a sure thing.

And say it worked out—what was the jackpot? Counting gum erasers and reordering Berol pads in a windowless supply room? Filling out endless ration forms just to order the stuff? Bearing the abuse and demands of actual illustrators and art directors, whose job he should have? Fun.

No, at this rate, he was likely going to have to head home to Michigan, maybe help out at his uncle’s farm in St. Johns till he could retrain himself as a lefty.

So it was with a sense of defeat and lean prospects that he sought out a room at a walk-up hotel he’d gotten off a list from the VA. Jobs aside, he didn’t even feel that upbeat about the chance of scrounging a good meal. It was almost five. Chow time wasn’t that far off, and checking in had already put him down another buck fifty.

After hanging his one extra shirt on the hook on his door, he lay back on the clangy little bed—no worse than Government Issue, but he’d grown used to the nonreg hammocks and hooch pads of the South Pacific. He tried to lie cadaver straight, not wanting to wrinkle his suit for the job hunt ahead, and stared out the window at a billboard across the street. Of course, it was imploring him to buy U.S. bonds.

“Sure thing, Unc,” he said to himself. “First nickel I earn.”

He wished he at least had a book to read. Maybe, with a book, he could distract himself enough to stay in the room all night and skip going out and wasting what little coin he had in his pocket tying one on. Maybe if it were a really engaging read, he could manage to distract himself enough to skip dinner, too.

Already he was thinking what places there were to eat around the hotel and how much it would put him out.

He realized then that he was on Adams. Chesty’s camera shop was on Adams, the number not far off from his hotel address. He figured he might as well go look up the guy’s wife and check that errand off the list.

2

She’d been keeping it from Chesty, but the camera shop just wasn’t making it. It hadn’t done well before Pearl, during the Depression, but with the war on now, folks’ loose money had other practical purposes than camera equipment or even getting film developed. Occasionally, someone brought in their old Brownie to be repaired, and there were ardent hobbyists who simply

had to splurge, but for the most part, the shop was a leaky boat, losing money every month her husband had been away.

Sal tried to make up the difference as best she could moonlighting at the Trib as a darkroom tech. She’d spoken to an editor about picking up an assignment as a photographer. He was an admirer of Chesty’s and so wasn’t overtly rude about it, but did say, “We’re not quite there yet, Sal.”

He offered to put in a word for her in the secretarial pool, but she told him she couldn’t type. It wasn’t true—she’d earned A’s in typing class two straight years in high school—but it hadn’t come down to being a secretary yet. Doing that would mean full-time, daytime hours, hence closing the shop. We’re not quite there yet, she thought.

One of the other possibilities she hadn’t fully explored was something she found in the back of the photography magazines they sold at the shop—small ads, phrased with discretion, asking for girlie photos. Typically, they said things like:

WE BUY ART PHOTOS

$$$ paid for QUALITY pics

With Male Appeal

Life Study • Naturist • Sun Worship

For publishing/mass market

Very Reasonable Offers

She’d gone as far as writing a few of them—queries only, with only two or three photos enclosed—asking for a little more guidance in terms of subject matter.

She thought she had a pretty good idea what they were driving at.

The photos she enclosed she shot herself, as samples. To make sure they didn’t just steal them and reproduce them—though it would be hard to do, grainy and raw looking, shooting from the print, not the negative—she’d further stymied them in any potential attempt to steal the shots by running a big X across the face in each with a grease pencil.

The face, of course, was her face. She’d decided to pose for these practice shots herself, using a timer gizmo of her husband’s own devising. No sense going to the trouble of hunting up subjects and shelling out a modeling fee for something she wasn’t sure could even turn a profit.

In the first, she was standing behind a wingback chair, her breasts resting on the back of it, peeking over the top. She

didn’t enjoy the look of her large nipples in that one. They seemed to be staring back at the camera like the wide eyes of

an owl.

The second was her sitting in the chair, legs tucked up under her chin, her arms wrapped around the whole business, hiding her goodies as best she could. Expressionwise, she’d been trying for coy and coquettish, but she looked, she thought, more like she had some sort of intestinal issues, maybe an ulcer or just really bad heartburn.

The third, she just lay on her tummy on a towel on the floor, at a right angle to the camera, her chin propped up on her hands, her head tipped slightly in the direction of the tripod. To her, her grin seemed pasted on, but it was x-ed out, anyway, and besides, these were just test shots.

After practicing a manlier hand, she signed the queries S. Dean Chesterton. It was her name, after all—Dean was her maiden name—but she wasn’t surprised when one of the replies began with Dear Dean.

Two things did surprise her: they offered up no criticism of her composition and lighting. She knew she didn’t have Chesty’s eye, but they’d failed to mention these flaws. And the second surprise was she’d shown too much skin:

Today’s wartime pinups are running a tad more conservative, Dean. Ease up on the flesh.

We want to show the boys in uniform what they’re fighting for, but the USO does not like dispensing anything that might get them thinking the girls back home are too sexed up & easy & begging for it.

More girl-next-door brunette is big right now--less blonde bombshell. Long leg shots. Think mild distraction, Dean. (Just enough to get the boys hot, not enough to get them worried and going AWOL!)

And speaking of uniforms, may we suggest that’s a great way to dress up your model. Half a sailor’s tunic, maybe an aviator’s cap, cocked at a flirty angle. Get the girls saluting, waving flags, straddling cannons--that sort of thing.

Another, hand scribbled, just said:

Think “home fires burning,” Mac—not “my pussy’s on fire.” Maybe next time.

This last had Sal a little taken aback—no one had ever used that word in addressing her before. Even if it was only written and not spoken out loud, it was a little jarring. Besides, she hadn’t shown her pussy, for Pete’s sake. Merely her bottom and her legs and her bosom, especially in that one that came off as an owl impression.

All the responses said the grease pencil Xs were unnecessary, that they were legitimate brokers and not in the business of using any photographer’s work without legal authority and complete monetary compensation.

Legitimate, she thought. Right.

She’d have to give it a little more consideration before proceeding.

On a warm June day in 1944, Wink Dutton, known most recently to the U.S. Army as Staff Sergeant Winton S. Dutton, special correspondent and burgeoning cartoonist and illustrator, stepped out onto the streets of Chicago in his civvies. In his pocket, he had seventeen dollars, the address of his buddy’s camera shop, a short list of publishers and advertising agencies, and the Purple Heart awarded to him for misunderstanding an ensign’s instructions regarding a flywheel aboard a sub he was supposed to be working up a piece on for the pages of Yank magazine.

The ensign had probably told him more than clearly to “Keep your finger out of this here,” but given the effects of a bottle of peach brandy the night before—a gift from a grateful quartermaster colonel for the boldly rugged rendering he’d done of him to accompany an article about fruitcake distribution and Christmas morale—the submarine tour seemed more like a cacophony of alarms, whistles, bells, and bellowing. He couldn’t think of a worse post-brandy story than, possibly, covering a riveter’s competition at a shipyard. Between the banging in his head and the banging in the tin can that was the USS _____________ (name censored for military secrecy), the only message he was able to receive was “Be sure to touch this flywheel I’m pointing to.”

He didn’t actually lose the hand, just proper use of the middle finger down to the pinky, plus the tip of the middle finger, right where he rested his pencils, pens, and paintbrushes.

“It’s the fuck finger and then some,” the navy doctor informed him. “You can still pinch, of course.”

“Great,” he’d told him. “I’ll put in for a transfer to the Pinching Brigade. I’ll get right on that.”

Before Wink shipped out of Townsville, Queensland, Sergeant Bill Chesterton, known to his fellow correspondents and poker players as Chesty, stopped by to say good-bye and good luck—and since Wink was planning on heading to Chicago, could he check in on his wife, Sal, and tell her he loved her still and was still being true?

“Absolutely,” he told him, and resisted horsing around with any cheap jokes—offering to do more than that for him or doubt the man’s statement of fidelity. It was the sort of thing guys did, the way they kidded, but personally, he thought it was a little too mean and a little too easy. And a little too close to the sort of demoralizing crap guys could hear plenty just by dialing in Tokyo Rose on the radio.

Besides, he counted himself lucky for having no such serious attachments—either back in the States or in the Pacific

theater—and it was only this luck, he knew, that kept him from being such a vulnerable, miserable, hang-faced slob.

He made four stabs at the job search that first day in Chicago. All three interviewers were respectful and very complimentary of his portfolio. The two that seemed at least on the ball enough to assess his new situation—that he wouldn’t be able to illustrate or cartoon anymore and that the third thing he did marginally well, writing copy, was also limited as he had yet to relearn how to write with the other hand, and it left his typing appallingly more hunt-and-peck—nevertheless agreed that he would still make a great art director. Unfortunately, neither one currently had any art director positions available. At one of the four stops, an ad agency that was doing a lot of promotional poster work for the bond drive, he was told they might be needing a new stock boy in the art department soon, but that wouldn’t happen for another month and only if the husband of the girl currently holding the job got shipped stateside, in which case they imagined she would most likely want to quit work and return to taking care of her home. It hardly sounded like a sure thing.

And say it worked out—what was the jackpot? Counting gum erasers and reordering Berol pads in a windowless supply room? Filling out endless ration forms just to order the stuff? Bearing the abuse and demands of actual illustrators and art directors, whose job he should have? Fun.

No, at this rate, he was likely going to have to head home to Michigan, maybe help out at his uncle’s farm in St. Johns till he could retrain himself as a lefty.

So it was with a sense of defeat and lean prospects that he sought out a room at a walk-up hotel he’d gotten off a list from the VA. Jobs aside, he didn’t even feel that upbeat about the chance of scrounging a good meal. It was almost five. Chow time wasn’t that far off, and checking in had already put him down another buck fifty.

After hanging his one extra shirt on the hook on his door, he lay back on the clangy little bed—no worse than Government Issue, but he’d grown used to the nonreg hammocks and hooch pads of the South Pacific. He tried to lie cadaver straight, not wanting to wrinkle his suit for the job hunt ahead, and stared out the window at a billboard across the street. Of course, it was imploring him to buy U.S. bonds.

“Sure thing, Unc,” he said to himself. “First nickel I earn.”

He wished he at least had a book to read. Maybe, with a book, he could distract himself enough to stay in the room all night and skip going out and wasting what little coin he had in his pocket tying one on. Maybe if it were a really engaging read, he could manage to distract himself enough to skip dinner, too.

Already he was thinking what places there were to eat around the hotel and how much it would put him out.

He realized then that he was on Adams. Chesty’s camera shop was on Adams, the number not far off from his hotel address. He figured he might as well go look up the guy’s wife and check that errand off the list.

2

She’d been keeping it from Chesty, but the camera shop just wasn’t making it. It hadn’t done well before Pearl, during the Depression, but with the war on now, folks’ loose money had other practical purposes than camera equipment or even getting film developed. Occasionally, someone brought in their old Brownie to be repaired, and there were ardent hobbyists who simply

had to splurge, but for the most part, the shop was a leaky boat, losing money every month her husband had been away.

Sal tried to make up the difference as best she could moonlighting at the Trib as a darkroom tech. She’d spoken to an editor about picking up an assignment as a photographer. He was an admirer of Chesty’s and so wasn’t overtly rude about it, but did say, “We’re not quite there yet, Sal.”

He offered to put in a word for her in the secretarial pool, but she told him she couldn’t type. It wasn’t true—she’d earned A’s in typing class two straight years in high school—but it hadn’t come down to being a secretary yet. Doing that would mean full-time, daytime hours, hence closing the shop. We’re not quite there yet, she thought.

One of the other possibilities she hadn’t fully explored was something she found in the back of the photography magazines they sold at the shop—small ads, phrased with discretion, asking for girlie photos. Typically, they said things like:

WE BUY ART PHOTOS

$$$ paid for QUALITY pics

With Male Appeal

Life Study • Naturist • Sun Worship

For publishing/mass market

Very Reasonable Offers

She’d gone as far as writing a few of them—queries only, with only two or three photos enclosed—asking for a little more guidance in terms of subject matter.

She thought she had a pretty good idea what they were driving at.

The photos she enclosed she shot herself, as samples. To make sure they didn’t just steal them and reproduce them—though it would be hard to do, grainy and raw looking, shooting from the print, not the negative—she’d further stymied them in any potential attempt to steal the shots by running a big X across the face in each with a grease pencil.

The face, of course, was her face. She’d decided to pose for these practice shots herself, using a timer gizmo of her husband’s own devising. No sense going to the trouble of hunting up subjects and shelling out a modeling fee for something she wasn’t sure could even turn a profit.

In the first, she was standing behind a wingback chair, her breasts resting on the back of it, peeking over the top. She

didn’t enjoy the look of her large nipples in that one. They seemed to be staring back at the camera like the wide eyes of

an owl.

The second was her sitting in the chair, legs tucked up under her chin, her arms wrapped around the whole business, hiding her goodies as best she could. Expressionwise, she’d been trying for coy and coquettish, but she looked, she thought, more like she had some sort of intestinal issues, maybe an ulcer or just really bad heartburn.

The third, she just lay on her tummy on a towel on the floor, at a right angle to the camera, her chin propped up on her hands, her head tipped slightly in the direction of the tripod. To her, her grin seemed pasted on, but it was x-ed out, anyway, and besides, these were just test shots.

After practicing a manlier hand, she signed the queries S. Dean Chesterton. It was her name, after all—Dean was her maiden name—but she wasn’t surprised when one of the replies began with Dear Dean.

Two things did surprise her: they offered up no criticism of her composition and lighting. She knew she didn’t have Chesty’s eye, but they’d failed to mention these flaws. And the second surprise was she’d shown too much skin:

Today’s wartime pinups are running a tad more conservative, Dean. Ease up on the flesh.

We want to show the boys in uniform what they’re fighting for, but the USO does not like dispensing anything that might get them thinking the girls back home are too sexed up & easy & begging for it.

More girl-next-door brunette is big right now--less blonde bombshell. Long leg shots. Think mild distraction, Dean. (Just enough to get the boys hot, not enough to get them worried and going AWOL!)

And speaking of uniforms, may we suggest that’s a great way to dress up your model. Half a sailor’s tunic, maybe an aviator’s cap, cocked at a flirty angle. Get the girls saluting, waving flags, straddling cannons--that sort of thing.

Another, hand scribbled, just said:

Think “home fires burning,” Mac—not “my pussy’s on fire.” Maybe next time.

This last had Sal a little taken aback—no one had ever used that word in addressing her before. Even if it was only written and not spoken out loud, it was a little jarring. Besides, she hadn’t shown her pussy, for Pete’s sake. Merely her bottom and her legs and her bosom, especially in that one that came off as an owl impression.

All the responses said the grease pencil Xs were unnecessary, that they were legitimate brokers and not in the business of using any photographer’s work without legal authority and complete monetary compensation.

Legitimate, she thought. Right.

She’d have to give it a little more consideration before proceeding.

Recenzii

“Playful… Sweet…. A novel with all the happy gloss of a romantic comedy.” —The New York Times Book Review

“Amick’s expertly crafted novel combines an unusual love story with an intriguing, atmospheric peek into the American graphic-art world in the 1940s.” —People

“Pitch-perfect. . . . Amick gives us something increasingly rare—a love story with heart.” —Associated Press

“A quirky, touching, and at times refreshingly masculine valentine. As [Amick] immerses us richly and authentically in an era essential to the formation of our national identity, he offers . . . a reminder, when we need it most, of why America remains a country with a vast potential for greatness.” —Julia Glass, author of Three Junes

“Amick’s expertly crafted novel combines an unusual love story with an intriguing, atmospheric peek into the American graphic-art world in the 1940s.” —People

“Pitch-perfect. . . . Amick gives us something increasingly rare—a love story with heart.” —Associated Press

“A quirky, touching, and at times refreshingly masculine valentine. As [Amick] immerses us richly and authentically in an era essential to the formation of our national identity, he offers . . . a reminder, when we need it most, of why America remains a country with a vast potential for greatness.” —Julia Glass, author of Three Junes

Descriere

From the author of the widely praised novel "The Lake, the River & the Other Lake" comes this love story of a man and a woman who choose an unconventional way to redefine themselves during and after World War II.

Premii

- Michigan Notable Books Winner, 2010