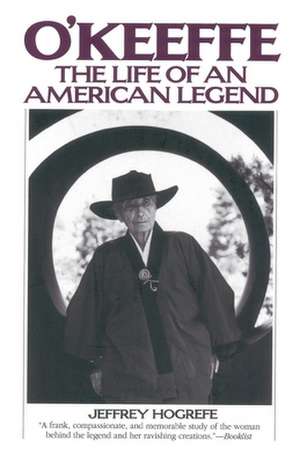

O'Keefe: The Life of an American Legend

Autor Jeffrey Hogrefeen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 noi 1999

Journalist and author Jeffrey Hogrefe discloses the answers to these questions and more in O'Keeffe, a richly detailed biography that illuminates much of the mystery and intrigue that surround Georgia O'Keeffe, and finally reveals the real woman behind the legend. Hogrefe's encounter with the ninety-three-year-old artist and with Juan Hamilton, the young man she loved in her final years, provided him with unique insights into her private world, as well as into Hamilton's own controversial relationship with O'Keeffe during the last fourteen years of her life.

Her acerbic personality, her unconventional lifestyle, and her struggles as an artist and a woman are brought to life in this definitive biography.

Preț: 144.84 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 217

Preț estimativ în valută:

27.71€ • 28.94$ • 22.89£

27.71€ • 28.94$ • 22.89£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553380699

ISBN-10: 0553380699

Pagini: 448

Dimensiuni: 140 x 218 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.63 kg

Ediția:Bantam Trade Pb.

Editura: Bantam

ISBN-10: 0553380699

Pagini: 448

Dimensiuni: 140 x 218 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.63 kg

Ediția:Bantam Trade Pb.

Editura: Bantam

Extras

Prologue

In the spring of 1973 a hapless young wanderer with hair down his back and only memories in his pockets arrived in a remote outpost on New Mexico's high desert. He told people he had been sent there, clear across the continent, by a spirit. He was not embarrassed to say so. Most of the residents of Abiquiu were not put off by John Bruce Hamilton--better known as Juan--and his other worlds. Isolated by high mountains and wide arid plains, in remote parts of New Mexico--like Abiquiu--natives occupied virtually the same sphere as their eighteenth-century Spanish forebears. It was believed that witches cast spells and snakes flew in the night. Grown men beat themselves with whips made of cactus barbs in the name of religion.

Being driven across the continent by a spirit was as commonplace as long sunsets and fantastic landforms in Abiquiu--a small place in a big land, peopled with a few hundred natives of a unique mixture of Arab, Basque, Spanish, and American Indian blood and consisting of a saloon with a swinging door, a one-room general store complete with saddles and tack, a collection of flat-roofed buildings made out of red mud, a large Catholic church--and an old white woman who lived by herself behind a high wall. Though some called her a bruja, or witch, she called herself an artist.

Having turned in conventional clothes for patched jeans, faded flannel shirts, a three-day-old beard, a bushy moustache, and a VW van coated with road dust, twenty-six-year-old Juan Hamilton looked like a troubadour or a gypsy or a hippie--depending on your point of view. Sometimes he wore his brown hair braided in a long Chinese-style pigtail. Sometimes his hair cascaded across his shoulders and down his back freely. A tall man, slender and long-waisted, he had a way of walking that suggested there was no rush. He slunk. He used his brown eyes to good effect, either narrowing them to a squint to indicate displeasure or opening them wide like a puppy dog to please. Words left his mouth softly in a twang, like that of a lugubrious country and western singer. Some women found him sexy. Some men found him ornery. He liked to laugh.

Hamilton had driven thousands of miles across America to find and care for Georgia Totto O'Keeffe, an eighty-five-year-old artist whose impact on American culture was so enormous that no one was certain what to make of her--least of all, how to care for her. Hamilton believed he did. Something had told him he might find a place in her life. A spirit had taken hold of him. It compelled him to move into the unknown. It drove him across the continent and into what looked like a biblical firmament. "I believed," he said, "that maybe she was alone and needed a friend."

Successful beyond the dreams of most women and men, O'Keeffe operated a feudal empire in a vast desert valley. Seemingly fortified behind high adobe walls and across miles of cactus-covered plain, the artist was not exactly well situated to welcome strangers into her world. Over the years she had carefully trained people to accept her imperious ways and to do things as she wished to support the myth of who she was. Once O'Keeffe complained that she had to put up with a person who cared for her "her way," because she did not have time to train her "in mine." Even as a young girl, long before she achieved success, O'Keeffe had felt she could control others by using what she considered her special powers of persuasion. "When so few people ever think at all," she asked a friend, with remarkable cynicism for a fourteen-year-old, "isn't it all right for me to think for them and get them to do what I want?"

With the aid of a large staff and faithful companions, she got people to do what she wanted and had arranged her life so that, between two houses some twenty miles apart, she could enjoy various desert landscapes from which she drew the subjects for most of her paintings. From one house, the sun rose in the morning over a verdant river valley; from another, the sun went down across bizarre land formations. O'Keeffe was enthralled by the desert. She referred to it romantically as if it were a make-believe place, and in some ways it was. She called it "The Faraway," "the end of the earth," or "mad country." "It is really absurd in a way," she wrote, "to just love country as I love this--."

In the twenties, as the first woman artist to excel in America alongside men, O'Keeffe became, for legions of women who had recently acquired the right to vote, "a religion," according to her late husband and guiding light, photographer and art impresario Alfred Stieglitz. The union between these two artists became the stuff of legend, but O'Keeffe's own fame came to exceed that of her already famous husband. Her sexually charged paintings of large flowers, in which people saw both male and female genitalia, attracted hordes of fans who sought her presence as if she were a movie star. She retreated to Abiquiu, where she found the solitude she desired as the only Anglo woman in a tiny village of fierce Spanish-speaking natives. "My pleasant disposition," she once remarked, "likes the world with nobody in it."

The myth of Georgia O'Keeffe grew in proportion to her isolation. Five decades later, occupying a "world with nobody in it" in her own Shangri-la, she still held America's imagination in her spell. As an octogenarian recluse who rarely ventured beyond the open space of Abiquiu, the artist attracted a new generation of disciples who wanted to be near her and know her, as if she were the Oracle of Delphi or the Dalai Lama. Unlike her initial following, which had been primarily female and largely urban, these pilgrims were both male and female, urban and rural, and sometimes were sorely misinformed about who the artist was. But for them, who she was was not as important as what she stood for. Garbed in long black dresses like a nineteenth-century widow, veiled like a nun, growing her own produce in a harsh desert--a person of the earth--she symbolized bravery at a time when many felt compelled to live outside civilization, a period marred by America's invasion of Vietnam.

A conscientious objector to the Vietnam War, John Bruce Hamilton was born during the post-World War 11 baby boom, in Dallas, Texas, on December 23, 1946, the first and last child of his parents' marriage. He was raised in South America and New Jersey in a strict religious atmosphere. Allen, his father, a tall Texan with a slow drawl and quick temper, was a missionary who developed education programs for children of Presbyterian converts in Colombia and Venezuela and later held an executive position at the United Presbyterian headquarters in New York. A large Bible, opened to a passage for each day, rested on a lectern in the hallway of their house.

Hamilton encountered the spirit that would draw him to New Mexico in his van at Lake George, New York, where O'Keeffe and Stieglitz had spent their summers in the twenties and thirties in the Stieglitz family compound. As he drove along the shoreline late at night, past old mansions sunk into deep woods of pine and birch, Hamilton says, a premonition that O'Keeffe needed care came to him out of the mist on the clear blue water.

Hamilton had been heading from Vermont to his parents' house in New Jersey when he heard the voice. He was going home to recoup from a personal defeat and to gather strength to move on in his life. Following a brief and tumultuous union, during which he and his first wife had built a cabin in the woods of Vermont, she had asked him to leave. He now felt abandoned and scared. He was aware that O'Keeffe and Stieglitz had spent time at Lake George because his estranged wife had hung a reproduction of an O'Keeffe painting titled Lake George with Crows (1921) on a wall of their simple cabin. His first wife had been devoted to Georgia O'Keeffe's work. Hamilton, too, admired the artist's use of space and light.

On arriving at his parents' home, Hamilton confided to them what had happened to his marriage. When they asked what he was going to do, he did not tell them about the voice or about his secret mission. He simply said he planned to spend a summer in New Mexico. His father offered to introduce Juan to his colleague, Jim Hall, who ran Ghost Ranch Conference Center in Abiquiu. Coincidentally, one of O'Keeffe's houses was on the grounds of Ghost Ranch, a remote retreat covering twenty-three thousand acres of badland--so named, according to legend, because from time to time the voice of a woman crying in the night for her dead husband had been heard echoing in the sandstone canyons.

Finding the artist would not be so easy. Looking for Georgia O'Keeffe was one of the main tourist draws to remote Abiquiu. Over the years dedicated fans of the artist had employed all sorts of means to get through to her, but she had increasingly learned how to avoid them in the style of Greta Garbo, who wanted to be alone. Once, the story goes, a group of art students knocked on the gate to her house. O'Keeffe opened the gate herself. After listening to their request--they said they wanted to see Georgia O'Keeffe--the artist held them to their word and put on a show. "Front side," she said coldly. "Back side," she said, turning around. "Good-bye!" she added, slamming shut the gate.

When he arrived in New Mexico, Hamilton told nearly everyone he met his story: that he was an artist who had lived in Vermont and wanted to meet the great artist. People sympathized with him, but they would not help him. Seven months passed before he even spotted Q'Keeffe driving her car. He lived simply, traveling, sleeping, and eating in his van. He swam naked on hot days in the cool waters of the snow-fed Chama River. Life was lazy. There were a number of large communes in the area. Hamilton found out where they were and began spending time with various commune members who, like himself, had dropped out of society to live in the wilds of northern New Mexico.

One day, he was working in the maintenance department at Ghost Ranch when one of his co-workers asked if he wanted to go to O'Keeffe's house with him. Hamilton seized the opportunity. Something was wrong with the plumbing in her house, and she wanted Juan's co-worker to fix it for her. It was a summer day. The cottonwoods along the river drooped in the desert heat. Rattlesnakes sunbathed along dirt roadbeds. As he passed boulders the size of elephants and mounds of purple-colored earth shaped like cones on the approach to her house, it seemed he was entering another planet. A sandstone cliff, striated with bands of red and yellow, rose thousands of feet overhead, casting a long dark shadow.

On the patio of the U-shaped hacienda, bushy sage plants grew out of cracks in a flagstone patio. There was not another building in sight. A watercress salad glistened in an old Indian basket on a rough wooden table. Various skulls and rocks were arranged haphazardly around the interior of the cool, dark hacienda. Stark Navajo blankets--black crosses against a white background--covered the floors. Hamilton had never seen such a world, or met such a person.

O'Keeffe was a thin woman of medium height and small bones, with a face of coinlike clarity, like Abraham Lincoln's. There was a time when, because she was dark-skinned, people thought she was an American Indian, and she allowed them their fantasy--even promoted it herself. She was in fact a mixture of Irish, Dutch, English, and Hungarian blood--born of American parents in a woodframe farmhouse in the prairie of Wisconsin. Her brown eyes were focused in a narrow gaze, seeming to miss nothing. Her face was etched with what seemed a million wrinkles from constant exposure to the bright desert sun.

Her prominent Roman nose and high forehead were exaggerated by the way she pulled her steely gray hair from her face into a bun on the nape of her neck. She walked with a measured gait as deliberate as a metronome and as vigorous as that of someone decades younger. Her posture was so erect, it seemed she could have balanced a cup of hot tea on the crown of her head. People did not seem to scare her, and in fact, by the way she spoke to the maintenance man about the plumbing, it seemed that she was the one who did the scaring. "Dealing with Georgia is very easy," a person who had worked with her commented, "provided you do exactly what she wants."

Hamilton was in awe of O'Keeffe. He studied her carefully and observed the way she had had her house decorated and how she dressed and talked to the maintenance man. She did not seem to mind that he was staring at her and inspecting her house. She talked to the maintenance man about the plumbing, and when Hamilton looked at her, in an effort to get her attention, she returned his advance with a frightening reply: "She looked right past me," he later said, "as if I were transparent." She did not need him. She already had enough help. And anyway, she had already had years of experience in dealing with people who tried to invade her privacy. "You know about the Indian eye," she asked later, "that passes over you without lingering, as though you didn't exist? That was the way I used to look at the Presbyterians at the ranch, so they wouldn't become too friendly."

Not even the Indian eye would dissuade Hamilton, however. He was obsessed. Meeting and working for O'Keeffe became his mission. He would not take no for an answer. Finally, months later, after several aborted attempts, the young artist entered the elderly artist's life. He went to her main house in the pueblo at dawn. As a friend had instructed him, he waited outside the gate for the artist to come to him--then proceeded to the back door when she did not immediately appear. "I am not a creature of habit," O'Keeffe had told people--"the only habit I have is getting up and seeing the dawn come."

O'Keeffe may have been old and barely able to see, but she knew what to look for. Hamilton was a tall, broad young man who could surely carry a load for her. The men who had already worked for her were nearly as old as she--the young men of the village had abandoned the barren land to find work in cities. Since she had been raised on a nineteenth-century farm where itinerants had been the mainstay of her family's help, O'Keeffe was accustomed to hiring people off the road to do for her. These people were addressed imperiously without name. Hamilton was this kind of person. She called him "my boy."

Had she been better able to see, she would have noticed a striking resemblance between Hamilton and the young Alfred Stieglitz. Put their pictures together, and you would almost have the same man, separated by some eighty years. It was an eerie coincidence. O'Keeffe had not known Stieglitz when he was as young as Hamilton, but she had no doubt known him better than anyone else. Theirs had been a marriage about which books are written and movies are made. Like other women who marry older men, O'Keeffe had watched her husband die while she was still youthful. She had never remarried. The memory of Stieglitz remained a force in her life as she grew old. She told people that her male and female chow dogs represented herself and "Alfred."

What she did notice about Hamilton was his hands. His hands were like her own: long slender fingers and wide palms--working hands. She needed extra hands, and although she was not sure what to make of him, she asked him to stay and wrap paintings for her. O'Keeffe's hands were famous. Stieglitz had photographed them over and over, along with many other parts of her body. His ongoing portrait of her had spanned decades and included several hundred pictures of a striking woman in her thirties and forties in various stages of dress.

As Hamilton wrapped the paintings and put them into a wooden crate, she noticed that he was moving as she did: slowly and carefully, with measure and balance. A suspicious person who trusted no one, she watched carefully to make sure he did not steal from her. What she saw was impressive: He was wrapping the packages as she would have herself. Here was someone who operated her way without having to be told.

The meeting of the young artist and the old artist soon became the freshest installment in the myth of Georgia O'Keeffe. As its details acquired the elusiveness of the rest of her tale, they became stylized to fit O'Keeffe's self-conception. Hamilton embraced the myth and became its most vocal proponent. Even the story of how he came to work for her became a fable. It is clear that the truth has many faces.

O'Keeffe seemed to bask in the pale light of notoriety. Taking what people thought was a lover young enough to be her grandson was a fitting finale to a life of independence. When others told her they regretted that they no longer saw her now that Hamilton was caring for her, she would say something utterly mystical. Although she rarely spoke or wrote about her beliefs, preferring to let her paintings do her talking, she occasionally made a passing reference to a higher power at work in her life. This was one of those occasions. "Juan was sent to me," she would tell those who questioned his role in her life as she grew old and weak and frail. Almost all believed her.

In the spring of 1973 a hapless young wanderer with hair down his back and only memories in his pockets arrived in a remote outpost on New Mexico's high desert. He told people he had been sent there, clear across the continent, by a spirit. He was not embarrassed to say so. Most of the residents of Abiquiu were not put off by John Bruce Hamilton--better known as Juan--and his other worlds. Isolated by high mountains and wide arid plains, in remote parts of New Mexico--like Abiquiu--natives occupied virtually the same sphere as their eighteenth-century Spanish forebears. It was believed that witches cast spells and snakes flew in the night. Grown men beat themselves with whips made of cactus barbs in the name of religion.

Being driven across the continent by a spirit was as commonplace as long sunsets and fantastic landforms in Abiquiu--a small place in a big land, peopled with a few hundred natives of a unique mixture of Arab, Basque, Spanish, and American Indian blood and consisting of a saloon with a swinging door, a one-room general store complete with saddles and tack, a collection of flat-roofed buildings made out of red mud, a large Catholic church--and an old white woman who lived by herself behind a high wall. Though some called her a bruja, or witch, she called herself an artist.

Having turned in conventional clothes for patched jeans, faded flannel shirts, a three-day-old beard, a bushy moustache, and a VW van coated with road dust, twenty-six-year-old Juan Hamilton looked like a troubadour or a gypsy or a hippie--depending on your point of view. Sometimes he wore his brown hair braided in a long Chinese-style pigtail. Sometimes his hair cascaded across his shoulders and down his back freely. A tall man, slender and long-waisted, he had a way of walking that suggested there was no rush. He slunk. He used his brown eyes to good effect, either narrowing them to a squint to indicate displeasure or opening them wide like a puppy dog to please. Words left his mouth softly in a twang, like that of a lugubrious country and western singer. Some women found him sexy. Some men found him ornery. He liked to laugh.

Hamilton had driven thousands of miles across America to find and care for Georgia Totto O'Keeffe, an eighty-five-year-old artist whose impact on American culture was so enormous that no one was certain what to make of her--least of all, how to care for her. Hamilton believed he did. Something had told him he might find a place in her life. A spirit had taken hold of him. It compelled him to move into the unknown. It drove him across the continent and into what looked like a biblical firmament. "I believed," he said, "that maybe she was alone and needed a friend."

Successful beyond the dreams of most women and men, O'Keeffe operated a feudal empire in a vast desert valley. Seemingly fortified behind high adobe walls and across miles of cactus-covered plain, the artist was not exactly well situated to welcome strangers into her world. Over the years she had carefully trained people to accept her imperious ways and to do things as she wished to support the myth of who she was. Once O'Keeffe complained that she had to put up with a person who cared for her "her way," because she did not have time to train her "in mine." Even as a young girl, long before she achieved success, O'Keeffe had felt she could control others by using what she considered her special powers of persuasion. "When so few people ever think at all," she asked a friend, with remarkable cynicism for a fourteen-year-old, "isn't it all right for me to think for them and get them to do what I want?"

With the aid of a large staff and faithful companions, she got people to do what she wanted and had arranged her life so that, between two houses some twenty miles apart, she could enjoy various desert landscapes from which she drew the subjects for most of her paintings. From one house, the sun rose in the morning over a verdant river valley; from another, the sun went down across bizarre land formations. O'Keeffe was enthralled by the desert. She referred to it romantically as if it were a make-believe place, and in some ways it was. She called it "The Faraway," "the end of the earth," or "mad country." "It is really absurd in a way," she wrote, "to just love country as I love this--."

In the twenties, as the first woman artist to excel in America alongside men, O'Keeffe became, for legions of women who had recently acquired the right to vote, "a religion," according to her late husband and guiding light, photographer and art impresario Alfred Stieglitz. The union between these two artists became the stuff of legend, but O'Keeffe's own fame came to exceed that of her already famous husband. Her sexually charged paintings of large flowers, in which people saw both male and female genitalia, attracted hordes of fans who sought her presence as if she were a movie star. She retreated to Abiquiu, where she found the solitude she desired as the only Anglo woman in a tiny village of fierce Spanish-speaking natives. "My pleasant disposition," she once remarked, "likes the world with nobody in it."

The myth of Georgia O'Keeffe grew in proportion to her isolation. Five decades later, occupying a "world with nobody in it" in her own Shangri-la, she still held America's imagination in her spell. As an octogenarian recluse who rarely ventured beyond the open space of Abiquiu, the artist attracted a new generation of disciples who wanted to be near her and know her, as if she were the Oracle of Delphi or the Dalai Lama. Unlike her initial following, which had been primarily female and largely urban, these pilgrims were both male and female, urban and rural, and sometimes were sorely misinformed about who the artist was. But for them, who she was was not as important as what she stood for. Garbed in long black dresses like a nineteenth-century widow, veiled like a nun, growing her own produce in a harsh desert--a person of the earth--she symbolized bravery at a time when many felt compelled to live outside civilization, a period marred by America's invasion of Vietnam.

A conscientious objector to the Vietnam War, John Bruce Hamilton was born during the post-World War 11 baby boom, in Dallas, Texas, on December 23, 1946, the first and last child of his parents' marriage. He was raised in South America and New Jersey in a strict religious atmosphere. Allen, his father, a tall Texan with a slow drawl and quick temper, was a missionary who developed education programs for children of Presbyterian converts in Colombia and Venezuela and later held an executive position at the United Presbyterian headquarters in New York. A large Bible, opened to a passage for each day, rested on a lectern in the hallway of their house.

Hamilton encountered the spirit that would draw him to New Mexico in his van at Lake George, New York, where O'Keeffe and Stieglitz had spent their summers in the twenties and thirties in the Stieglitz family compound. As he drove along the shoreline late at night, past old mansions sunk into deep woods of pine and birch, Hamilton says, a premonition that O'Keeffe needed care came to him out of the mist on the clear blue water.

Hamilton had been heading from Vermont to his parents' house in New Jersey when he heard the voice. He was going home to recoup from a personal defeat and to gather strength to move on in his life. Following a brief and tumultuous union, during which he and his first wife had built a cabin in the woods of Vermont, she had asked him to leave. He now felt abandoned and scared. He was aware that O'Keeffe and Stieglitz had spent time at Lake George because his estranged wife had hung a reproduction of an O'Keeffe painting titled Lake George with Crows (1921) on a wall of their simple cabin. His first wife had been devoted to Georgia O'Keeffe's work. Hamilton, too, admired the artist's use of space and light.

On arriving at his parents' home, Hamilton confided to them what had happened to his marriage. When they asked what he was going to do, he did not tell them about the voice or about his secret mission. He simply said he planned to spend a summer in New Mexico. His father offered to introduce Juan to his colleague, Jim Hall, who ran Ghost Ranch Conference Center in Abiquiu. Coincidentally, one of O'Keeffe's houses was on the grounds of Ghost Ranch, a remote retreat covering twenty-three thousand acres of badland--so named, according to legend, because from time to time the voice of a woman crying in the night for her dead husband had been heard echoing in the sandstone canyons.

Finding the artist would not be so easy. Looking for Georgia O'Keeffe was one of the main tourist draws to remote Abiquiu. Over the years dedicated fans of the artist had employed all sorts of means to get through to her, but she had increasingly learned how to avoid them in the style of Greta Garbo, who wanted to be alone. Once, the story goes, a group of art students knocked on the gate to her house. O'Keeffe opened the gate herself. After listening to their request--they said they wanted to see Georgia O'Keeffe--the artist held them to their word and put on a show. "Front side," she said coldly. "Back side," she said, turning around. "Good-bye!" she added, slamming shut the gate.

When he arrived in New Mexico, Hamilton told nearly everyone he met his story: that he was an artist who had lived in Vermont and wanted to meet the great artist. People sympathized with him, but they would not help him. Seven months passed before he even spotted Q'Keeffe driving her car. He lived simply, traveling, sleeping, and eating in his van. He swam naked on hot days in the cool waters of the snow-fed Chama River. Life was lazy. There were a number of large communes in the area. Hamilton found out where they were and began spending time with various commune members who, like himself, had dropped out of society to live in the wilds of northern New Mexico.

One day, he was working in the maintenance department at Ghost Ranch when one of his co-workers asked if he wanted to go to O'Keeffe's house with him. Hamilton seized the opportunity. Something was wrong with the plumbing in her house, and she wanted Juan's co-worker to fix it for her. It was a summer day. The cottonwoods along the river drooped in the desert heat. Rattlesnakes sunbathed along dirt roadbeds. As he passed boulders the size of elephants and mounds of purple-colored earth shaped like cones on the approach to her house, it seemed he was entering another planet. A sandstone cliff, striated with bands of red and yellow, rose thousands of feet overhead, casting a long dark shadow.

On the patio of the U-shaped hacienda, bushy sage plants grew out of cracks in a flagstone patio. There was not another building in sight. A watercress salad glistened in an old Indian basket on a rough wooden table. Various skulls and rocks were arranged haphazardly around the interior of the cool, dark hacienda. Stark Navajo blankets--black crosses against a white background--covered the floors. Hamilton had never seen such a world, or met such a person.

O'Keeffe was a thin woman of medium height and small bones, with a face of coinlike clarity, like Abraham Lincoln's. There was a time when, because she was dark-skinned, people thought she was an American Indian, and she allowed them their fantasy--even promoted it herself. She was in fact a mixture of Irish, Dutch, English, and Hungarian blood--born of American parents in a woodframe farmhouse in the prairie of Wisconsin. Her brown eyes were focused in a narrow gaze, seeming to miss nothing. Her face was etched with what seemed a million wrinkles from constant exposure to the bright desert sun.

Her prominent Roman nose and high forehead were exaggerated by the way she pulled her steely gray hair from her face into a bun on the nape of her neck. She walked with a measured gait as deliberate as a metronome and as vigorous as that of someone decades younger. Her posture was so erect, it seemed she could have balanced a cup of hot tea on the crown of her head. People did not seem to scare her, and in fact, by the way she spoke to the maintenance man about the plumbing, it seemed that she was the one who did the scaring. "Dealing with Georgia is very easy," a person who had worked with her commented, "provided you do exactly what she wants."

Hamilton was in awe of O'Keeffe. He studied her carefully and observed the way she had had her house decorated and how she dressed and talked to the maintenance man. She did not seem to mind that he was staring at her and inspecting her house. She talked to the maintenance man about the plumbing, and when Hamilton looked at her, in an effort to get her attention, she returned his advance with a frightening reply: "She looked right past me," he later said, "as if I were transparent." She did not need him. She already had enough help. And anyway, she had already had years of experience in dealing with people who tried to invade her privacy. "You know about the Indian eye," she asked later, "that passes over you without lingering, as though you didn't exist? That was the way I used to look at the Presbyterians at the ranch, so they wouldn't become too friendly."

Not even the Indian eye would dissuade Hamilton, however. He was obsessed. Meeting and working for O'Keeffe became his mission. He would not take no for an answer. Finally, months later, after several aborted attempts, the young artist entered the elderly artist's life. He went to her main house in the pueblo at dawn. As a friend had instructed him, he waited outside the gate for the artist to come to him--then proceeded to the back door when she did not immediately appear. "I am not a creature of habit," O'Keeffe had told people--"the only habit I have is getting up and seeing the dawn come."

O'Keeffe may have been old and barely able to see, but she knew what to look for. Hamilton was a tall, broad young man who could surely carry a load for her. The men who had already worked for her were nearly as old as she--the young men of the village had abandoned the barren land to find work in cities. Since she had been raised on a nineteenth-century farm where itinerants had been the mainstay of her family's help, O'Keeffe was accustomed to hiring people off the road to do for her. These people were addressed imperiously without name. Hamilton was this kind of person. She called him "my boy."

Had she been better able to see, she would have noticed a striking resemblance between Hamilton and the young Alfred Stieglitz. Put their pictures together, and you would almost have the same man, separated by some eighty years. It was an eerie coincidence. O'Keeffe had not known Stieglitz when he was as young as Hamilton, but she had no doubt known him better than anyone else. Theirs had been a marriage about which books are written and movies are made. Like other women who marry older men, O'Keeffe had watched her husband die while she was still youthful. She had never remarried. The memory of Stieglitz remained a force in her life as she grew old. She told people that her male and female chow dogs represented herself and "Alfred."

What she did notice about Hamilton was his hands. His hands were like her own: long slender fingers and wide palms--working hands. She needed extra hands, and although she was not sure what to make of him, she asked him to stay and wrap paintings for her. O'Keeffe's hands were famous. Stieglitz had photographed them over and over, along with many other parts of her body. His ongoing portrait of her had spanned decades and included several hundred pictures of a striking woman in her thirties and forties in various stages of dress.

As Hamilton wrapped the paintings and put them into a wooden crate, she noticed that he was moving as she did: slowly and carefully, with measure and balance. A suspicious person who trusted no one, she watched carefully to make sure he did not steal from her. What she saw was impressive: He was wrapping the packages as she would have herself. Here was someone who operated her way without having to be told.

The meeting of the young artist and the old artist soon became the freshest installment in the myth of Georgia O'Keeffe. As its details acquired the elusiveness of the rest of her tale, they became stylized to fit O'Keeffe's self-conception. Hamilton embraced the myth and became its most vocal proponent. Even the story of how he came to work for her became a fable. It is clear that the truth has many faces.

O'Keeffe seemed to bask in the pale light of notoriety. Taking what people thought was a lover young enough to be her grandson was a fitting finale to a life of independence. When others told her they regretted that they no longer saw her now that Hamilton was caring for her, she would say something utterly mystical. Although she rarely spoke or wrote about her beliefs, preferring to let her paintings do her talking, she occasionally made a passing reference to a higher power at work in her life. This was one of those occasions. "Juan was sent to me," she would tell those who questioned his role in her life as she grew old and weak and frail. Almost all believed her.

Recenzii

"A frank, compassionate, and memorable study of the woman behind the legend and her ravishing creations."

--Booklist

"This engrossing biography of Georgia O'Keeffe sweeps away myths and legends....a remarkable piece of detective work."

--Publishers Weekly

"Hogrefe manages to be both fair and compassionate in his treatment of a difficult woman--who also happens to be one of our most dazzling national treasures."

--Edmund White

"A historic, in-depth study of what it means to risk one's life to be an artist. It is also a depiction of sexual confusions, ironic outrage and rage, and the shedding of society's armor to create a female knight in pursuit of a vision. Georgia O'Keeffe is the one woman who was there first in the world of art."

--Sandra Hochman

--Booklist

"This engrossing biography of Georgia O'Keeffe sweeps away myths and legends....a remarkable piece of detective work."

--Publishers Weekly

"Hogrefe manages to be both fair and compassionate in his treatment of a difficult woman--who also happens to be one of our most dazzling national treasures."

--Edmund White

"A historic, in-depth study of what it means to risk one's life to be an artist. It is also a depiction of sexual confusions, ironic outrage and rage, and the shedding of society's armor to create a female knight in pursuit of a vision. Georgia O'Keeffe is the one woman who was there first in the world of art."

--Sandra Hochman

Notă biografică

Jeffrey Hogrefe