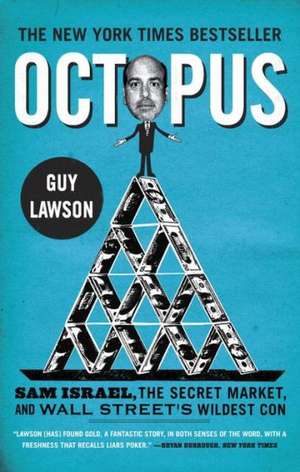

Octopus: Sam Israel, the Secret Market, and Wall Street's Wildest Con

Autor Guy Lawsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 8 iul 2013

But it was all an elaborate charade. After suffering devastating losses and fabricating fake returns, Israel knew it was only a matter of time before his real performance would be discovered. So when a former black-ops agent told him about a “secret market” run by the Fed, Israel bet his last $150 million on a chance to make billions.

Thus began his bizarre journey into “the Upperworld”—a society populated by clandestine bankers, shady European nobility, and spooks issuing cryptic warnings about a mysterious cabal known as the Octopus.

Preț: 114.19 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 171

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.85€ • 22.81$ • 18.08£

21.85€ • 22.81$ • 18.08£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307716088

ISBN-10: 0307716082

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0307716082

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

GUY LAWSON has traveled the world reporting on war, crime, politics, and sports. His work has appeared in the New York Times, Harper's, GQ, and Rolling Stone. He and his live in upstate New York.

Extras

Chapter One

Trust

All Sam Israel ever wanted to be was a Wall Street trader. For generations, the men of the Israel family had been prominent and hugely successful commodities traders. For nearly a century they and their cousins the Arons had been major players trading in coffee, sugar, cocoa, rubber, soy, precious metals-the substance of modern American life. Along the way, the family became fantastically wealthy. Long before the term was coined, the Israels were real-life Masters of the Universe.

But it was Wall Street that attracted Sam, not the commodities market. As a boy growing up in New Orleans he'd sat on the lap of his legendary grandfather, Samuel Israel Jr., watching the ticker tape from the New York Stock Exchange and imagining what life was like in that distant place. When the Israels moved to New York and his father took a senior position in the family business, which had grown into a multi-billion-dollar multinational conglomerate named ACLI, Sam dreamed about trading stock in the skyscrapers of Lower Manhattan.

In the summer of 1978, at the age of eighteen, Sam got the chance to try his luck. At the time, he was a newly minted graduate of Hackley, an elite prep school outside New York City. Although the Israels were very rich, Sam was expected to earn his own pocket money. Thus he was spending the summer working odd jobs and training to try out for the freshman football team at Tulane University, alma mater of his father and grandfather. In the Israel family it was assumed that Sam would go to work for ACLI when he finished college. He was smart, charming, athletic, extremely likable. But Sam had a propensity for lying. In his mind, they were harmless lies, teenage lies, about girls, sports, deeds of derring-do. It was his way to be liked, to be funny, to get attention, to make himself feel good.

Sam had been blessed with all the good fortune any young man could hope for. But he didn't want to follow in the footsteps of his illustrious ancestors. He didn't want to be the beneficiary of nepotism, with all of its attendant resentments and insecurities. Despite the Israel family's outward appearance of perfection, Sam's relationship with his father was deeply troubled. Sam wanted to be his own man, shaping his own destiny, proving his own worth.

"My father asked me if I wanted to come into the family business," Israel recalled. "But I said no. I didn't want to be like my father in any way. I was only a kid, but I could see what was going on. My father had gone into the business, and his father had treated him poorly. My grandfather was always on my father about one thing or another. Nothing could ever please my grandfather. My father was doomed to that life. He was never going to break away and be on his own. It would've been the same for me.

"If I became a Wall Street trader, I wouldn't be working for my father. I'd be trading stocks instead of commodities. It may seem like a small distinction, but it was huge to me. At my father's business I'd be the kid who had been born into the right family. On Wall Street I'd be on my own. I was always told that the New York Stock Exchange was the greatest place on earth. It was where the smartest people went. It was the hardest place to get ahead. Wall Street traders lived by their wits. It wouldn't matter that my last name was Israel. It wouldn't matter who my father and grandfather were. On Wall Street, anybody could make it-if they were tough enough and smart enough."

One fine June afternoon in his eighteenth year, Sam was working as a bartender at a garden party in his uncle's backyard. The crowd was middle-aged, well dressed, seemingly unremarkable-pretty wives and pale-faced men with paunches and high blood pressure, drinking too much, smoking too much. But Sam knew that beneath the milquetoast appearances, these men were Wall Street's ruling class.

Standing behind the bar, Sam was approached by a heavyset man in search of a cocktail. The man was just under six feet tall, weighed more than two hundred pounds, and had an unruly mane of brown hair and a ruddy complexion. He was wearing expensive clothes, but he was slightly disheveled and had the twinkle in his eye of a prankster. Sam instantly recognized him. Standing before Sam was the famous Freddy Graber-the man they called "the King" on Wall Street. Sam had heard his father and uncles talk about Graber's exploits. Still only in his early thirties, Graber was already famous for his unbelievable ability to trade stocks.

Instead of accepting a partnership offer at Lehman Brothers, Graber had started something called a "hedge fund." In the seventies, hedge funds were exceptionally rare and mysterious, a secret realm run by the high priests of high finance. Only the wealthiest people even knew of the existence of hedge funds. Only the greatest traders gained entrée to the select society. Freddy Graber was in that number. His hedge fund acted as a broker for major investment banks, clipping a few pennies in commission for executing trades on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange for companies like Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley.

But Graber's true genius was the way he traded his own money. Unlike most Wall Street traders, Graber didn't bet with other people's money. This was a dare within a dare. Normally traders who "ran" money invested funds given to them by banks, insurance companies, pension funds, high-net worth individuals. Not Graber. He traded for himself exclusively. His stake in the early seventies had been $400,000. In less than a decade he'd turned it into $23 million. Cash. It was the kind of feat that had made the Israel men famous. In 1898 Sam's great-uncle Leon Israel had started with $10,000, and by 1920 he had $25 million-the equivalent of $500 million today.

Graber carried himself with confidence that bordered on arrogance. But at the same time he was unpretentious, quick to grin, instantly likable. He was also a serious drinker. Graber asked the young Israel for a vodka and cranberry juice on the rocks, with a chunk of lime. Israel handed over the drink and introduced himself-knowing his last name would be recognized. But Graber didn't take much notice of the eager teenager.

When Graber returned for another drink a few minutes later, though, Sam was ready. "Vodka and cranberry on the rocks," Sam said, mixing the cocktail before Graber could order. "With a chunk of lime."

"You have a good memory, kid," Graber said. "You any good with numbers?"

"I'm very good with numbers," Israel said.

"You could make a living doing what I do," Graber said.

"I'd love to see what you do, Mr. Graber," Israel said.

"Come up and see me anytime," Graber said, handing over his card. "The door is always open."

From Graber's offhand manner, Israel knew it was an empty invitation. But Sam wasn't going to let this opportunity pass him by. The next Monday morning, he dressed in his best suit and caught the early train to Manhattan.

"When I walked up the subway stairs into the sunlight at the corner of Wall Street and Broadway for the first time it was like I was entering a new universe," Israel remembered. "The streets were teeming with action. Secretaries hustled by. Shoe shine guys, newsstand boys, hot dog vendors, everyone was on the make. To me it was the most incredible place on earth. It was like a giant casino. It was pure glamour. It was everything I'd dreamt about."

Frederic J. Graber and Company operated on the thirtieth floor of 1 New York Plaza, a fifty-story skyscraper that housed Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and powerful law firms. Graber's trading room was in a suite of offices with a dozen or so other independent hedge funds. At the time there were only a few hundred funds running perhaps a few billion dollars, compared with the trillion-dollar industry that would emerge in the coming decades. Israel stood awkwardly at the threshold watching the early-morning commotion. Sitting behind a large marble desk in the trading pit, Graber didn't recognize Israel at first. Then Sam summoned the courage to remind the older man of his offer. Graber grinned at Israel's nerve. He could have sent Israel away, but he was gregarious by nature and inclined to be generous, and Sam was obviously keen. Graber sent Sam down to the trading floor to see how things worked there. By sending him to the floor, Graber was making it plain that Sam was on his own. It could easily have been his first and last day. But Sam had other plans.

In the late seventies the floor of the New York Stock Exchange was a madhouse, a roiling sea of humanity being tossed by waves of greed and fear. The exchange was divided into a series of rooms, each with huge boards to record the hundreds of millions of dollars being traded at every moment, each filled with brokers and clerks screaming their orders and jostling for every eighth of a point. In this oversized fraternity house, the kind of place where men played Pin the Tail on the Donkey and sprayed shaving cream for practical jokes, the intensity was so high a trader could fall over from a heart attack and trading wouldn't stop. There would be a moment of concern, perhaps, as the trader lay gasping on the floor, but trading would go on as the paramedics arrived with a stretcher and took him away.

The teenage Israel walked through the pandemonium for the first time in a state of awe. The floor was chaotic, but the action was also choreographed. Brokers with numbers on their chests took orders from clerks, who worked banks of phones; runners known as "squads" sped the orders to specialists, who checked the trades and then posted them to the ticker tape on the big board. The noise and speed were bewildering. Buffeted by the mob, Sam slowly found his way to Graber's booth, number 0020. The tiny space was crammed with a hundred telephones, each connected to a different broker. There stood Graber's trading clerk, a short, dark-haired, stout man twenty years older than Israel-Phil Ratner.

"Phil was a tough old bird who knew everything about trading," Israel recalled. "By the time I made it to the floor it was nearly lunchtime. I watched, but no one was really talking to me or telling me anything. Not that they were rude, they were just busy. So Phil sent me to get pizza. I went and bought eight large pies, with extra cheese, extra toppings. When I got back to the floor, I was stopped at the door. The guy working security told me that food wasn't allowed on the floor. All the phones and wires in the systems would be damaged if people took food or drink onto the floor. But I wasn't to be denied. I started to argue. The governor of the floor came over and started screaming at me for bringing pizzas into the exchange, asking me who the fuck I thought I was. I pointed at Phil and I said, 'That man over there has the power to give me a job, and I'm not going to lose that chance. I'm bringing him these pizzas unless you knock me out.' I was a kid. I still had zits. I shoved past the governor of the exchange. That was how determined I was to please those men.

"Phil and the guys started pissing themselves laughing. The governor was bent over double. It was all a setup-a prank. They wanted to see if I had the mettle. I was being hazed. I laughed along with them-I pretended to laugh. But I was very serious. Nothing was going to stop me from becoming a trader. At the end of the day, I asked Phil if I could come back the next day. Just to watch, I said. I was scared he was going to say no. But he took pity on me, I guess. Or he thought I would be good for a laugh. Being able to laugh at yourself, that was one of the most important things on the Street. Phil said okay. From that day forward, I was in, and no one was going to get me out."

Sam spent the rest of the summer as a runner on the floor of the NYSE with Phil and his crew of clerks. Graber had an account at the members' smoke shop in the NYSE, so Sam was sent to fetch cigarettes and snacks. In idle moments, Sam was taught "liar's poker," a game of chance, based on gambling on the serial numbers of dollars, that prized the ability to deceive. The floor of the exchange was completely foreign to the well-heeled teenager, and he set about learning its ways with the attention to detail of an aspiring samurai. "Downstairs" was the name for the floor. "Upstairs" was where Freddy Graber and the other traders made their decisions about buying and selling.

"All of the brokers downstairs came from Brooklyn and Staten Island-they talked in 'dem's and 'dose,'" Sam recalled. "Lots of them had no college education, but they made a lot of money considering their backgrounds. A good broker could make a couple of hundred thousand a year, back when that was real money. The lead guys were like Mafia dons. You had to pay your respects to them or you weren't going to get into the specialists' booth. Upstairs was completely different. It was suits and ties. The guys on the floor were real street guys. But I loved it on the floor. I would stay late to do the work nobody else wanted to do, making sure the accounts were straight and all the tickets for the trades were clean and accurate. Everything was done on paper in those days, so it was tedious work, but it was a way for me to ingratiate myself. Just because my name was Israel, and I was known as a rich kid, I wasn't above doing the grunt work."

At home in Westchester on the weekends, Sam moved inside circles of enormous wealth and prestige. The Israels were fixtures at the Century Country Club, perhaps the single most exclusive golf club in the country. The crowd at the Century Club included many of the world's most powerful people. Sam read about their exploits as he rode the train to the city every day. "They were the crème de la crème," Israel recalled. "My father's friends were captains of industry. Presidents of investment banks. The heads of major multinational companies. Alan Greenspan before he took over the Federal Reserve. Sandy Weill, who became the chairman of Citibank. Larry Tisch, who became a billionaire as the CEO of CBS.

Trust

All Sam Israel ever wanted to be was a Wall Street trader. For generations, the men of the Israel family had been prominent and hugely successful commodities traders. For nearly a century they and their cousins the Arons had been major players trading in coffee, sugar, cocoa, rubber, soy, precious metals-the substance of modern American life. Along the way, the family became fantastically wealthy. Long before the term was coined, the Israels were real-life Masters of the Universe.

But it was Wall Street that attracted Sam, not the commodities market. As a boy growing up in New Orleans he'd sat on the lap of his legendary grandfather, Samuel Israel Jr., watching the ticker tape from the New York Stock Exchange and imagining what life was like in that distant place. When the Israels moved to New York and his father took a senior position in the family business, which had grown into a multi-billion-dollar multinational conglomerate named ACLI, Sam dreamed about trading stock in the skyscrapers of Lower Manhattan.

In the summer of 1978, at the age of eighteen, Sam got the chance to try his luck. At the time, he was a newly minted graduate of Hackley, an elite prep school outside New York City. Although the Israels were very rich, Sam was expected to earn his own pocket money. Thus he was spending the summer working odd jobs and training to try out for the freshman football team at Tulane University, alma mater of his father and grandfather. In the Israel family it was assumed that Sam would go to work for ACLI when he finished college. He was smart, charming, athletic, extremely likable. But Sam had a propensity for lying. In his mind, they were harmless lies, teenage lies, about girls, sports, deeds of derring-do. It was his way to be liked, to be funny, to get attention, to make himself feel good.

Sam had been blessed with all the good fortune any young man could hope for. But he didn't want to follow in the footsteps of his illustrious ancestors. He didn't want to be the beneficiary of nepotism, with all of its attendant resentments and insecurities. Despite the Israel family's outward appearance of perfection, Sam's relationship with his father was deeply troubled. Sam wanted to be his own man, shaping his own destiny, proving his own worth.

"My father asked me if I wanted to come into the family business," Israel recalled. "But I said no. I didn't want to be like my father in any way. I was only a kid, but I could see what was going on. My father had gone into the business, and his father had treated him poorly. My grandfather was always on my father about one thing or another. Nothing could ever please my grandfather. My father was doomed to that life. He was never going to break away and be on his own. It would've been the same for me.

"If I became a Wall Street trader, I wouldn't be working for my father. I'd be trading stocks instead of commodities. It may seem like a small distinction, but it was huge to me. At my father's business I'd be the kid who had been born into the right family. On Wall Street I'd be on my own. I was always told that the New York Stock Exchange was the greatest place on earth. It was where the smartest people went. It was the hardest place to get ahead. Wall Street traders lived by their wits. It wouldn't matter that my last name was Israel. It wouldn't matter who my father and grandfather were. On Wall Street, anybody could make it-if they were tough enough and smart enough."

One fine June afternoon in his eighteenth year, Sam was working as a bartender at a garden party in his uncle's backyard. The crowd was middle-aged, well dressed, seemingly unremarkable-pretty wives and pale-faced men with paunches and high blood pressure, drinking too much, smoking too much. But Sam knew that beneath the milquetoast appearances, these men were Wall Street's ruling class.

Standing behind the bar, Sam was approached by a heavyset man in search of a cocktail. The man was just under six feet tall, weighed more than two hundred pounds, and had an unruly mane of brown hair and a ruddy complexion. He was wearing expensive clothes, but he was slightly disheveled and had the twinkle in his eye of a prankster. Sam instantly recognized him. Standing before Sam was the famous Freddy Graber-the man they called "the King" on Wall Street. Sam had heard his father and uncles talk about Graber's exploits. Still only in his early thirties, Graber was already famous for his unbelievable ability to trade stocks.

Instead of accepting a partnership offer at Lehman Brothers, Graber had started something called a "hedge fund." In the seventies, hedge funds were exceptionally rare and mysterious, a secret realm run by the high priests of high finance. Only the wealthiest people even knew of the existence of hedge funds. Only the greatest traders gained entrée to the select society. Freddy Graber was in that number. His hedge fund acted as a broker for major investment banks, clipping a few pennies in commission for executing trades on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange for companies like Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley.

But Graber's true genius was the way he traded his own money. Unlike most Wall Street traders, Graber didn't bet with other people's money. This was a dare within a dare. Normally traders who "ran" money invested funds given to them by banks, insurance companies, pension funds, high-net worth individuals. Not Graber. He traded for himself exclusively. His stake in the early seventies had been $400,000. In less than a decade he'd turned it into $23 million. Cash. It was the kind of feat that had made the Israel men famous. In 1898 Sam's great-uncle Leon Israel had started with $10,000, and by 1920 he had $25 million-the equivalent of $500 million today.

Graber carried himself with confidence that bordered on arrogance. But at the same time he was unpretentious, quick to grin, instantly likable. He was also a serious drinker. Graber asked the young Israel for a vodka and cranberry juice on the rocks, with a chunk of lime. Israel handed over the drink and introduced himself-knowing his last name would be recognized. But Graber didn't take much notice of the eager teenager.

When Graber returned for another drink a few minutes later, though, Sam was ready. "Vodka and cranberry on the rocks," Sam said, mixing the cocktail before Graber could order. "With a chunk of lime."

"You have a good memory, kid," Graber said. "You any good with numbers?"

"I'm very good with numbers," Israel said.

"You could make a living doing what I do," Graber said.

"I'd love to see what you do, Mr. Graber," Israel said.

"Come up and see me anytime," Graber said, handing over his card. "The door is always open."

From Graber's offhand manner, Israel knew it was an empty invitation. But Sam wasn't going to let this opportunity pass him by. The next Monday morning, he dressed in his best suit and caught the early train to Manhattan.

"When I walked up the subway stairs into the sunlight at the corner of Wall Street and Broadway for the first time it was like I was entering a new universe," Israel remembered. "The streets were teeming with action. Secretaries hustled by. Shoe shine guys, newsstand boys, hot dog vendors, everyone was on the make. To me it was the most incredible place on earth. It was like a giant casino. It was pure glamour. It was everything I'd dreamt about."

Frederic J. Graber and Company operated on the thirtieth floor of 1 New York Plaza, a fifty-story skyscraper that housed Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and powerful law firms. Graber's trading room was in a suite of offices with a dozen or so other independent hedge funds. At the time there were only a few hundred funds running perhaps a few billion dollars, compared with the trillion-dollar industry that would emerge in the coming decades. Israel stood awkwardly at the threshold watching the early-morning commotion. Sitting behind a large marble desk in the trading pit, Graber didn't recognize Israel at first. Then Sam summoned the courage to remind the older man of his offer. Graber grinned at Israel's nerve. He could have sent Israel away, but he was gregarious by nature and inclined to be generous, and Sam was obviously keen. Graber sent Sam down to the trading floor to see how things worked there. By sending him to the floor, Graber was making it plain that Sam was on his own. It could easily have been his first and last day. But Sam had other plans.

In the late seventies the floor of the New York Stock Exchange was a madhouse, a roiling sea of humanity being tossed by waves of greed and fear. The exchange was divided into a series of rooms, each with huge boards to record the hundreds of millions of dollars being traded at every moment, each filled with brokers and clerks screaming their orders and jostling for every eighth of a point. In this oversized fraternity house, the kind of place where men played Pin the Tail on the Donkey and sprayed shaving cream for practical jokes, the intensity was so high a trader could fall over from a heart attack and trading wouldn't stop. There would be a moment of concern, perhaps, as the trader lay gasping on the floor, but trading would go on as the paramedics arrived with a stretcher and took him away.

The teenage Israel walked through the pandemonium for the first time in a state of awe. The floor was chaotic, but the action was also choreographed. Brokers with numbers on their chests took orders from clerks, who worked banks of phones; runners known as "squads" sped the orders to specialists, who checked the trades and then posted them to the ticker tape on the big board. The noise and speed were bewildering. Buffeted by the mob, Sam slowly found his way to Graber's booth, number 0020. The tiny space was crammed with a hundred telephones, each connected to a different broker. There stood Graber's trading clerk, a short, dark-haired, stout man twenty years older than Israel-Phil Ratner.

"Phil was a tough old bird who knew everything about trading," Israel recalled. "By the time I made it to the floor it was nearly lunchtime. I watched, but no one was really talking to me or telling me anything. Not that they were rude, they were just busy. So Phil sent me to get pizza. I went and bought eight large pies, with extra cheese, extra toppings. When I got back to the floor, I was stopped at the door. The guy working security told me that food wasn't allowed on the floor. All the phones and wires in the systems would be damaged if people took food or drink onto the floor. But I wasn't to be denied. I started to argue. The governor of the floor came over and started screaming at me for bringing pizzas into the exchange, asking me who the fuck I thought I was. I pointed at Phil and I said, 'That man over there has the power to give me a job, and I'm not going to lose that chance. I'm bringing him these pizzas unless you knock me out.' I was a kid. I still had zits. I shoved past the governor of the exchange. That was how determined I was to please those men.

"Phil and the guys started pissing themselves laughing. The governor was bent over double. It was all a setup-a prank. They wanted to see if I had the mettle. I was being hazed. I laughed along with them-I pretended to laugh. But I was very serious. Nothing was going to stop me from becoming a trader. At the end of the day, I asked Phil if I could come back the next day. Just to watch, I said. I was scared he was going to say no. But he took pity on me, I guess. Or he thought I would be good for a laugh. Being able to laugh at yourself, that was one of the most important things on the Street. Phil said okay. From that day forward, I was in, and no one was going to get me out."

Sam spent the rest of the summer as a runner on the floor of the NYSE with Phil and his crew of clerks. Graber had an account at the members' smoke shop in the NYSE, so Sam was sent to fetch cigarettes and snacks. In idle moments, Sam was taught "liar's poker," a game of chance, based on gambling on the serial numbers of dollars, that prized the ability to deceive. The floor of the exchange was completely foreign to the well-heeled teenager, and he set about learning its ways with the attention to detail of an aspiring samurai. "Downstairs" was the name for the floor. "Upstairs" was where Freddy Graber and the other traders made their decisions about buying and selling.

"All of the brokers downstairs came from Brooklyn and Staten Island-they talked in 'dem's and 'dose,'" Sam recalled. "Lots of them had no college education, but they made a lot of money considering their backgrounds. A good broker could make a couple of hundred thousand a year, back when that was real money. The lead guys were like Mafia dons. You had to pay your respects to them or you weren't going to get into the specialists' booth. Upstairs was completely different. It was suits and ties. The guys on the floor were real street guys. But I loved it on the floor. I would stay late to do the work nobody else wanted to do, making sure the accounts were straight and all the tickets for the trades were clean and accurate. Everything was done on paper in those days, so it was tedious work, but it was a way for me to ingratiate myself. Just because my name was Israel, and I was known as a rich kid, I wasn't above doing the grunt work."

At home in Westchester on the weekends, Sam moved inside circles of enormous wealth and prestige. The Israels were fixtures at the Century Country Club, perhaps the single most exclusive golf club in the country. The crowd at the Century Club included many of the world's most powerful people. Sam read about their exploits as he rode the train to the city every day. "They were the crème de la crème," Israel recalled. "My father's friends were captains of industry. Presidents of investment banks. The heads of major multinational companies. Alan Greenspan before he took over the Federal Reserve. Sandy Weill, who became the chairman of Citibank. Larry Tisch, who became a billionaire as the CEO of CBS.

Recenzii

“Lawson [has] found gold…This is a fantastic story, in both senses of the word, with a freshness that recalls Liars Poker.”

—Bryan Burrough, New York Times

“Read this book to understand Wall Street…Someone is going to Octopus into a movie. By this time next year, Lawson will have a fat deal…The reason for that is that Octopus is an incredible dark comedy with one of the craziest true-life ironic twists you can possibly imagine."

—Matt Taibbi, Rolling Stone

"Lively...turns a lens on the fast and loose ways of Wall Street...would make an excellent gift for a regulatory complicance officer...or a shrink."

—Bloomberg Businessweek

"Lawson's spellbinding account of Sam Israel's rise and fall is a phantasmagoric trip through the larcenous outer reaches (as well as the dark heart) of the world of finance. Octopus made me worry that I was being followed or swindled."

—Nick Paumgarten, New Yorker

“A cautionary tale of the highly sophisticated, often endemic fraud that still lurks on Wall Street…I was riveted by Mr. Lawson’s telling…the story is mind-boggling.”

—Andrew Sorkin, New York Times (Dealbook)

“Entertaining…a colorful contemporary story about greed and ambition warping judgment, about con men duping other con men…replete with secret markets, shady intelligence operatives, and even a space alien that overdosed on ice cream.”

—Reuters

“Full on Twilight Zone…features not just rampant fraud but guns, supposed CIA double agents, drugs, JFK’s assassination, and oh yes, world domination. Did I mention that this is a nonfiction book?...An outrageous but definitely movie-worthy tale. Lawson’s reporting is prodigious.”

—Fortune

“Like The Sting…An astounding story that forces you to remind yourself that this actually happened not ten years ago, to real people with real money.”

—Maclean’s

“[Features] a series of spy-thriller escapades that could have been plucked from a Jason Bourne movie…More fun and thrilling than any work of journalism about hedge funds has the right to be.”

—Canadian Business

“An inside look at a savage tribal society [of Wall Street traders] that also reminds one of that rollicking farce concocted by Mel Brooks, ‘The Producers’… Brings to life one of the most colorful, and often engaging, con men of this or any other century…an entertaining, well-told tale.”

—Washington Times

“If you dig movies about cons, like Catch Me If You Can, The Sting, and The Spanish Prisoner, you will blow through Octopus, Guy Lawson’s deftly and enthusiastically told tale of Same Israel and the Bayou hedge fund.”

—The Daily Beast

“Penetratingly comprehensive…Lawson nimbly traverses the labyrinthine depths of a worldwide banking con that managed to involve looted Federal Reserve notes and the JFK assassination…An eye-opening window onto Wall Street’s destructive culture of unchecked hubris and a harrowing thrill ride into the unraveling mind of a desperate operator.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Lawson has mined the darkest, most seductive world I can imagine and delivered up a story that almost defies comprehension. Octopus is written with a force and clarity that I found absolutely irresistible…It’s a hell of a book.”

—Sebastian Junger, New York Times bestselling author of The Perfect Storm

"Liars and fraudsters and con men, oh my. Beyond the Bayou hedge fund implosion and faked suicide, Guy Lawson wonderfully winds the bizarre tale of Sam Israel's demise into a swirl of global conspiracy and ultimate delusion."

—Andy Kessler, New York Times bestselling author of Running Money and How We Got Here

"A scintillating real-life thriller about one of the most peculiar frauds in history…Part true-crime thriller, part Wall Street investigation, Octopus is filled with startling revelations.”

—Gary Weiss, former investigative reporter for Business Week and author of Born to Steal, Wall Street Versus America and Ayn Rand Nation

"An absorbing, splendidly detailed and darkly illuminating tale of our times.”

—David Whitford, Editor-at-Large, Fortune magazine

"A rollicking, roller-coaster ride of a book that is utterly impossible to put down. Crackling with energy, Guy Lawson's account of Sam Israel -- rogue Wall Street trader and grifter par excellence - and the con within a con within a con that led to his ruin is a story that no novelist could possibly make up. Forget the sniveling Bernie Madoff and his garden-variety Ponzi Scheme; for anyone wanting to understand just how truly crazy Wall Street became and why, this is the book to read."

—Scott Anderson, Vanity Fair contributor and author of Triage

"[Israel's Ponzi scheme] speaks to the banality of evil. But there is nothing banal about Guy Lawson's telling of the most incredible story I've ever heard in or out of Wall Street."

—Jared Dillian, author of Street Freak: Money and Madness at Lehman Brothers

"Thrilling, outrageous and true, Octopus is a riveting ride through the shadow world of global high finance. A desperate man with a touch of insanity, Sam Israel is a character straight out of what we could only wish this story were: fantastic fiction."

—Martin Kihn, author of House of Lies and Bad Dog (A Love Story)

—Bryan Burrough, New York Times

“Read this book to understand Wall Street…Someone is going to Octopus into a movie. By this time next year, Lawson will have a fat deal…The reason for that is that Octopus is an incredible dark comedy with one of the craziest true-life ironic twists you can possibly imagine."

—Matt Taibbi, Rolling Stone

"Lively...turns a lens on the fast and loose ways of Wall Street...would make an excellent gift for a regulatory complicance officer...or a shrink."

—Bloomberg Businessweek

"Lawson's spellbinding account of Sam Israel's rise and fall is a phantasmagoric trip through the larcenous outer reaches (as well as the dark heart) of the world of finance. Octopus made me worry that I was being followed or swindled."

—Nick Paumgarten, New Yorker

“A cautionary tale of the highly sophisticated, often endemic fraud that still lurks on Wall Street…I was riveted by Mr. Lawson’s telling…the story is mind-boggling.”

—Andrew Sorkin, New York Times (Dealbook)

“Entertaining…a colorful contemporary story about greed and ambition warping judgment, about con men duping other con men…replete with secret markets, shady intelligence operatives, and even a space alien that overdosed on ice cream.”

—Reuters

“Full on Twilight Zone…features not just rampant fraud but guns, supposed CIA double agents, drugs, JFK’s assassination, and oh yes, world domination. Did I mention that this is a nonfiction book?...An outrageous but definitely movie-worthy tale. Lawson’s reporting is prodigious.”

—Fortune

“Like The Sting…An astounding story that forces you to remind yourself that this actually happened not ten years ago, to real people with real money.”

—Maclean’s

“[Features] a series of spy-thriller escapades that could have been plucked from a Jason Bourne movie…More fun and thrilling than any work of journalism about hedge funds has the right to be.”

—Canadian Business

“An inside look at a savage tribal society [of Wall Street traders] that also reminds one of that rollicking farce concocted by Mel Brooks, ‘The Producers’… Brings to life one of the most colorful, and often engaging, con men of this or any other century…an entertaining, well-told tale.”

—Washington Times

“If you dig movies about cons, like Catch Me If You Can, The Sting, and The Spanish Prisoner, you will blow through Octopus, Guy Lawson’s deftly and enthusiastically told tale of Same Israel and the Bayou hedge fund.”

—The Daily Beast

“Penetratingly comprehensive…Lawson nimbly traverses the labyrinthine depths of a worldwide banking con that managed to involve looted Federal Reserve notes and the JFK assassination…An eye-opening window onto Wall Street’s destructive culture of unchecked hubris and a harrowing thrill ride into the unraveling mind of a desperate operator.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Lawson has mined the darkest, most seductive world I can imagine and delivered up a story that almost defies comprehension. Octopus is written with a force and clarity that I found absolutely irresistible…It’s a hell of a book.”

—Sebastian Junger, New York Times bestselling author of The Perfect Storm

"Liars and fraudsters and con men, oh my. Beyond the Bayou hedge fund implosion and faked suicide, Guy Lawson wonderfully winds the bizarre tale of Sam Israel's demise into a swirl of global conspiracy and ultimate delusion."

—Andy Kessler, New York Times bestselling author of Running Money and How We Got Here

"A scintillating real-life thriller about one of the most peculiar frauds in history…Part true-crime thriller, part Wall Street investigation, Octopus is filled with startling revelations.”

—Gary Weiss, former investigative reporter for Business Week and author of Born to Steal, Wall Street Versus America and Ayn Rand Nation

"An absorbing, splendidly detailed and darkly illuminating tale of our times.”

—David Whitford, Editor-at-Large, Fortune magazine

"A rollicking, roller-coaster ride of a book that is utterly impossible to put down. Crackling with energy, Guy Lawson's account of Sam Israel -- rogue Wall Street trader and grifter par excellence - and the con within a con within a con that led to his ruin is a story that no novelist could possibly make up. Forget the sniveling Bernie Madoff and his garden-variety Ponzi Scheme; for anyone wanting to understand just how truly crazy Wall Street became and why, this is the book to read."

—Scott Anderson, Vanity Fair contributor and author of Triage

"[Israel's Ponzi scheme] speaks to the banality of evil. But there is nothing banal about Guy Lawson's telling of the most incredible story I've ever heard in or out of Wall Street."

—Jared Dillian, author of Street Freak: Money and Madness at Lehman Brothers

"Thrilling, outrageous and true, Octopus is a riveting ride through the shadow world of global high finance. A desperate man with a touch of insanity, Sam Israel is a character straight out of what we could only wish this story were: fantastic fiction."

—Martin Kihn, author of House of Lies and Bad Dog (A Love Story)