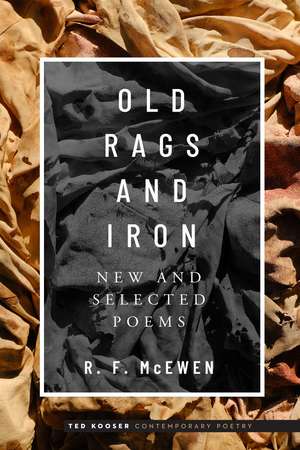

Old Rags and Iron: New and Selected Poems: Ted Kooser Contemporary Poetry

Autor R. F. McEwen Introducere de Ted Kooseren Limba Engleză Paperback – mar 2025

Set primarily in the back-of-the-yard neighborhood of South Side Chicago, where McEwen grew up, as well as Pine Ridge, South Dakota, western Nebraska, Ireland, and elsewhere, the poems celebrate many voices and stories. Utilizing tree-trimming as a central metaphor, these poems of blank verse fictions reverberate like truth.

Preț: 104.73 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 157

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.05€ • 21.78$ • 16.85£

20.05€ • 21.78$ • 16.85£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781496241894

ISBN-10: 1496241894

Pagini: 144

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Editura: Nebraska

Colecția University of Nebraska Press

Seria Ted Kooser Contemporary Poetry

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 1496241894

Pagini: 144

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Editura: Nebraska

Colecția University of Nebraska Press

Seria Ted Kooser Contemporary Poetry

Locul publicării:United States

Notă biografică

R. F. McEwen was born in Chicago, Illinois. Since 1962 he has been a professional logger and tree trimmer, and he has taught English in Chadron, Nebraska, since 1972. McEwen is the author of several books, most recently The Big Sandy, Bill’s Boys and Other Poems, and And There’s Been Talk . . .

Extras

Old Rags and Iron

There was an apple tree in our backyard,

and I remember balancing myself

against the wind in its green top. The apples, too,

were green, and I remember picking them

for pie my mother baked. It was a good

backyard, with rhubarb smack against the fence,

and farther back a weather-ravaged shed

we never used, until my mother fixed

a hoop against its side. And there I’d stand

and shoot against the world, against all time;

for morning lingered into afternoons,

and afternoons to long, descending dusks

that never fell until I’d won my game,

or mother called. And I remember well

the junkman and his wizened horse. They came

on Wednesday morning down the alley, where

in autumn we burned leaves; where the police

took rabid dogs to make them well; and where

on winter mornings tramps might keep a fire

in a rusty garbage can. This junkman, though,

it seemed he’d lost a lion by the name

of Rags. For over and again his voice

rang down the alley like a muffled bell,

its clapper wrapped in someone’s cast-off drawers.

“Old Rags, Old Rags the Lion,” was his cry

that, when I first remember hearing it,

had me believing he had Rags in tow,

that for a nickel one might view the beast

who, though he’d fallen on hard times, had once

been king.

It was late autumn, and the air

was heavy with a mist and lingering

leaf-smoke. I’d gone outside that morning, hard

upon my mother’s discontent with milk

that turned before it wet the glass, but more

with me: I’d moved the glass before she poured.

And when I heard the call announcing Rags

I called into the megaphone I’d made

my hands, “I’ll be right there.” And off I ran

with hope the man would stop just long enough

for me to see Old Rags. Then, “Stop! Wait up!”

I cried, confounded by my father’s coat

I’d worn against the rain, which caught, along

with clutching apple roots and unretrieved,

slow-rotting fruit, beneath my feet and pitched

me flailing on the apple-rancid ground.

And from my place I watched the horse pass by

and defecate. Its nostrils blew a stream

of heavy breath that sprayed the air with clots

of phlegm and mucous-weighted blood. It wore

a funnel-shaped fedora and a shawl

of emerald. And then I saw the man

and hailed him from my stew of muddy fruit;

“I want to see Old Rags,” I cried, my voice

a small tin whistle, shrill, at which he stopped his cart.

His back was bent, and he sat huddling

beneath a Turkish rug that formed a tent

about his shoulders and his head. Drawn on,

my head just level with the wheel’s top rim,

I heard within the tent the sound of raw,

long, grating coughs and sputtering. The air

that hovered at the entrance to the tent

was mingled with a staleness of smoke.

I stood below him in the mud; my eyes

were blank, my voice, except to say, “Old Rags,”

was gone. The soft rain, too, had gone from drops

to dampened air; the mist had cleared, the smoke

dispersed. And as I stood I couldn’t help

but send my glances slantways toward the cart.

But nothing rumbled, no, and nothing roared.

“If Rags is in there now,” I thought, “he’s off

to sleep, or sick.” But when the junkman turned

toward me and coughed, “Old Rags?” not glancing down,

I answered him, “I want to see Old Rags

the Lion.” “Then all aboard,” he said, “but don’t

be long.” And then he laughed, low, short, and mean,

“He wants to see old rags!”

But only heaps

of spongy gabardine, and shredded twists

of wilted felt, and steaming woolen scraps,

and greasy denim, corduroy in lumps

confronted me. Old Rags had bolted: “Free,”

I thought, while fear rose like a secret

in my throat. And with this revelation came

the sudden snapping of the junkman’s whip,

and then his gravel-burdened voice, “Move off

from there.” The wagon lurched, and I went down

into the mud still looking for Old Rags.

It was two years, I think, before I learned

the truth about Old Rags. Until that time

I played less in the yard, and when I did

I kept a weather eye for mottled shade

and always one ear cocked against the low,

voracious rumbling I knew would sound

his contemplation of a charge. And never

on a Wednesday would I play, unless indoors.

And always on a Wednesday I would hear,

come early morning on near breakfast time

after my father’d left for work, the sound

that, long years later, I remembered when

in northern Michigan, I heard far off

from shore the sound the ore boats make so late

at night when they are wallowing through fog.

“Old Rags, Old Rags the Lion, the Lion . . .”

And I, from safe inside, would always see

that grizzled man, aslump in summer with

a rainbow umbrella rattling

above his head, in fall and winter with

the Turkish rug; and always with a fresh,

more wizened horse, less lucky than the last

that must have died. But never did I see

the lion, Rags, or hear his deep marauding voice.

I never saw him springing from the mist,

or blend his tawny shadow with the trees.

And then one Wednesday when the night before

my ma had pulverized the house with cleaning up,

and gathered half a ton of junk, she heard

along with me the voice she’d waited for.

“Ah, that’ll be the man himself,” she said,

“the rags and iron man.” And then she turned

on me. “Get outta that,” she said, for I

was crouching near the pile. “Or would you stare

and watch me hauling this and never stir?”

Well, stir I did, and stir I have. Till now

it’s been mid-past full forty years since Rags

would, on a Wednesday, stalk our neighborhood

and make of our backyard his hunting ground.

My fear abated when I learned the truth,

and yet I’ve never lost entirely

my terror when I peered above the siding

of the junkman’s weathered cart and saw

old rags heaped listlessly like fallen men

and knew the Lion I was looking for

had fled. And it’s stayed with me all this time,

another rag of truth that nothing yet

in life’s caused me to shed or made less true:

I know the junkman never found Old Rags.

There was an apple tree in our backyard,

and I remember balancing myself

against the wind in its green top. The apples, too,

were green, and I remember picking them

for pie my mother baked. It was a good

backyard, with rhubarb smack against the fence,

and farther back a weather-ravaged shed

we never used, until my mother fixed

a hoop against its side. And there I’d stand

and shoot against the world, against all time;

for morning lingered into afternoons,

and afternoons to long, descending dusks

that never fell until I’d won my game,

or mother called. And I remember well

the junkman and his wizened horse. They came

on Wednesday morning down the alley, where

in autumn we burned leaves; where the police

took rabid dogs to make them well; and where

on winter mornings tramps might keep a fire

in a rusty garbage can. This junkman, though,

it seemed he’d lost a lion by the name

of Rags. For over and again his voice

rang down the alley like a muffled bell,

its clapper wrapped in someone’s cast-off drawers.

“Old Rags, Old Rags the Lion,” was his cry

that, when I first remember hearing it,

had me believing he had Rags in tow,

that for a nickel one might view the beast

who, though he’d fallen on hard times, had once

been king.

It was late autumn, and the air

was heavy with a mist and lingering

leaf-smoke. I’d gone outside that morning, hard

upon my mother’s discontent with milk

that turned before it wet the glass, but more

with me: I’d moved the glass before she poured.

And when I heard the call announcing Rags

I called into the megaphone I’d made

my hands, “I’ll be right there.” And off I ran

with hope the man would stop just long enough

for me to see Old Rags. Then, “Stop! Wait up!”

I cried, confounded by my father’s coat

I’d worn against the rain, which caught, along

with clutching apple roots and unretrieved,

slow-rotting fruit, beneath my feet and pitched

me flailing on the apple-rancid ground.

And from my place I watched the horse pass by

and defecate. Its nostrils blew a stream

of heavy breath that sprayed the air with clots

of phlegm and mucous-weighted blood. It wore

a funnel-shaped fedora and a shawl

of emerald. And then I saw the man

and hailed him from my stew of muddy fruit;

“I want to see Old Rags,” I cried, my voice

a small tin whistle, shrill, at which he stopped his cart.

His back was bent, and he sat huddling

beneath a Turkish rug that formed a tent

about his shoulders and his head. Drawn on,

my head just level with the wheel’s top rim,

I heard within the tent the sound of raw,

long, grating coughs and sputtering. The air

that hovered at the entrance to the tent

was mingled with a staleness of smoke.

I stood below him in the mud; my eyes

were blank, my voice, except to say, “Old Rags,”

was gone. The soft rain, too, had gone from drops

to dampened air; the mist had cleared, the smoke

dispersed. And as I stood I couldn’t help

but send my glances slantways toward the cart.

But nothing rumbled, no, and nothing roared.

“If Rags is in there now,” I thought, “he’s off

to sleep, or sick.” But when the junkman turned

toward me and coughed, “Old Rags?” not glancing down,

I answered him, “I want to see Old Rags

the Lion.” “Then all aboard,” he said, “but don’t

be long.” And then he laughed, low, short, and mean,

“He wants to see old rags!”

But only heaps

of spongy gabardine, and shredded twists

of wilted felt, and steaming woolen scraps,

and greasy denim, corduroy in lumps

confronted me. Old Rags had bolted: “Free,”

I thought, while fear rose like a secret

in my throat. And with this revelation came

the sudden snapping of the junkman’s whip,

and then his gravel-burdened voice, “Move off

from there.” The wagon lurched, and I went down

into the mud still looking for Old Rags.

It was two years, I think, before I learned

the truth about Old Rags. Until that time

I played less in the yard, and when I did

I kept a weather eye for mottled shade

and always one ear cocked against the low,

voracious rumbling I knew would sound

his contemplation of a charge. And never

on a Wednesday would I play, unless indoors.

And always on a Wednesday I would hear,

come early morning on near breakfast time

after my father’d left for work, the sound

that, long years later, I remembered when

in northern Michigan, I heard far off

from shore the sound the ore boats make so late

at night when they are wallowing through fog.

“Old Rags, Old Rags the Lion, the Lion . . .”

And I, from safe inside, would always see

that grizzled man, aslump in summer with

a rainbow umbrella rattling

above his head, in fall and winter with

the Turkish rug; and always with a fresh,

more wizened horse, less lucky than the last

that must have died. But never did I see

the lion, Rags, or hear his deep marauding voice.

I never saw him springing from the mist,

or blend his tawny shadow with the trees.

And then one Wednesday when the night before

my ma had pulverized the house with cleaning up,

and gathered half a ton of junk, she heard

along with me the voice she’d waited for.

“Ah, that’ll be the man himself,” she said,

“the rags and iron man.” And then she turned

on me. “Get outta that,” she said, for I

was crouching near the pile. “Or would you stare

and watch me hauling this and never stir?”

Well, stir I did, and stir I have. Till now

it’s been mid-past full forty years since Rags

would, on a Wednesday, stalk our neighborhood

and make of our backyard his hunting ground.

My fear abated when I learned the truth,

and yet I’ve never lost entirely

my terror when I peered above the siding

of the junkman’s weathered cart and saw

old rags heaped listlessly like fallen men

and knew the Lion I was looking for

had fled. And it’s stayed with me all this time,

another rag of truth that nothing yet

in life’s caused me to shed or made less true:

I know the junkman never found Old Rags.

Cuprins

Acknowledgments

Introduction by Ted Kooser

"Old Rags and Iron" & Other Narratives

Old Rags and Iron

Cotton Bishop’s Good Sleep

A Round on Jackson’s Trace

A Strong Wind Clear and Keen

Ash Hollow

Bill Richard’s Boy

Hammer Ring

John Hanks’s Blue Hound

Fragment from a Larger Poem

Crossing

Dad’s Way

Dust to Dust

High Hawk: Eugene Pierce, His Passing (1998–2017)

In the Pines

Incident at the Bus Stop

Kadokah

Lion’s Head: Cass County, Nebraska, 1953

Lost Tracks at Sorley’s Creek

Moody Boatright’s “Dead Dad Ditty”

Nick’s Night

On the Wing

Parrot Pal

Second Shift at Tilden Steel

Snow Man

Spelling Wilson James: Blue Island, Illinois, 1967

The Honcho River and Its Run

The Wind along the Crest

Well-Found at Neilly’s Creek

The Rising of Rock Fowler Creek

George Corchran’s Later Blow

Tree Trimmer’s Paradise

To Jim D. Manning, Tree Man: Who Died in His Tree June 1983

Late October: Richardson and Early Storms

Bill Ward’s Winter Break

Absent Crew

John Early Poems

Their Last Lad’s Fishing

Early Rising

John Early Remembers: The Moment of His Wife’s Death

Sonnet for the Lost and Found

On Looking Back

John Early Wonders, Waiting Dawn

White River Poems

Tracks Don’t Lie

Panaderia

The Lessoning

Buried Deep at Fast Horse Creek

Aunt Rose in Great Demand

Lean Jack MacBride: A Fragment

From Prairie Schooner, 1991–2005

Tuckered In, Tuckered Out

Wings

Snow Gazer

Quare Garden at the Dry End of the State

Gill Bronsen’s Dream

Irish Poems

Back to Old Mhaigh Eo

The Far Side of Red Bay

Small Favors

For Agnes Maddy Conlin (1892–1953): On the Occasion of Her Funeral

Her Way with Words, with Life: Aileen O’Lyne (1993–2018)

Double Shift

Introduction by Ted Kooser

"Old Rags and Iron" & Other Narratives

Old Rags and Iron

Cotton Bishop’s Good Sleep

A Round on Jackson’s Trace

A Strong Wind Clear and Keen

Ash Hollow

Bill Richard’s Boy

Hammer Ring

John Hanks’s Blue Hound

Fragment from a Larger Poem

Crossing

Dad’s Way

Dust to Dust

High Hawk: Eugene Pierce, His Passing (1998–2017)

In the Pines

Incident at the Bus Stop

Kadokah

Lion’s Head: Cass County, Nebraska, 1953

Lost Tracks at Sorley’s Creek

Moody Boatright’s “Dead Dad Ditty”

Nick’s Night

On the Wing

Parrot Pal

Second Shift at Tilden Steel

Snow Man

Spelling Wilson James: Blue Island, Illinois, 1967

The Honcho River and Its Run

The Wind along the Crest

Well-Found at Neilly’s Creek

The Rising of Rock Fowler Creek

George Corchran’s Later Blow

Tree Trimmer’s Paradise

To Jim D. Manning, Tree Man: Who Died in His Tree June 1983

Late October: Richardson and Early Storms

Bill Ward’s Winter Break

Absent Crew

John Early Poems

Their Last Lad’s Fishing

Early Rising

John Early Remembers: The Moment of His Wife’s Death

Sonnet for the Lost and Found

On Looking Back

John Early Wonders, Waiting Dawn

White River Poems

Tracks Don’t Lie

Panaderia

The Lessoning

Buried Deep at Fast Horse Creek

Aunt Rose in Great Demand

Lean Jack MacBride: A Fragment

From Prairie Schooner, 1991–2005

Tuckered In, Tuckered Out

Wings

Snow Gazer

Quare Garden at the Dry End of the State

Gill Bronsen’s Dream

Irish Poems

Back to Old Mhaigh Eo

The Far Side of Red Bay

Small Favors

For Agnes Maddy Conlin (1892–1953): On the Occasion of Her Funeral

Her Way with Words, with Life: Aileen O’Lyne (1993–2018)

Double Shift

Recenzii

“R. F. McEwen’s collection presents a compelling chorus of voices in different tones and registers, and widely dispersed across time, place, and human experience. McEwen masterfully revives here the noble tradition of the extended poetic narrative, adding richly and intensively to that enduring poetic tradition that his poems at once amplify and enrich. Meticulously conducted and finely detailed in language, image, and emotional intensity, these are brawny poems that we shall not easily forget. They set root in the mind, reminding us, through the moving voices and histories of the characters we meet in them, of the terrible and terrifying adventure of human community, of the triumph and torment that, in all its extraordinary diversity, unites us all, branches upon a deep-rooted tree that reach ever toward the sky.”—Stephen Behrendt, George Holmes Distinguished Professor of English emeritus at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

“We enter the world of these narrative poems like Robert Frost’s rider of birches—a whiplash to the eye as you make your way into the tangled twigs, then a fantasy taking flight on bent branches up through the traumas of childhood through the arc of adulthood, from winds having their say, stops along the road outside Kadokah, the rising White River or Fast Horse Creek, up the tree trimmer’s hold, down the streets of vagrants and rolling bottles, from Chicago to reservation towns, past the complications of families mixed and otherwise, across the waters to the Emerald Island itself. These poems thrust us up and out of the page a while, then bring us back down firmly on Earth, good both going and coming, unsettling and exhilarating in the same sweep. No discussion of Great Plains literature is complete without at least one trip into the understory with R. F. McEwen as your guide.”—Matt Evertson, professor of English at Western Colorado University

“R. F. McEwen’s Old Rags and Iron is a generous and joyful gathering of work written across a lifetime. In finely crafted narrative poems, McEwen gives eloquent and tender voice to the human and the nonhuman worlds that harbor his subjects. He reminds us that wherever there are people, there are animals and trees, all contending with or enjoying the seasons in Nebraska, Illinois, Iowa, and Ireland. Both mythic figures like Lonesome Frank in ‘Hammer Ring’ and an old aunt in ‘A Strong Wind Clear and Keen’—‘I see her still, my mother’s aunt, her feet like freezing soldiers doddering along’—come vibrantly alive in the distinctive, sparkling, and wonderful poems that compose this collection.”—Eamonn Wall, author of My Aunts at Twilight Poker

Descriere

Using tree-trimming as one of several central metaphors, Old Rags and Iron is a collection of narrative poems about the life experiences of working-class people.