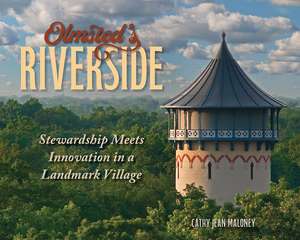

Olmsted's Riverside: Stewardship Meets Innovation in a Landmark Village

Autor Cathy Jean Maloneyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 18 dec 2024

Just outside the bustling metropolis of Chicago lies the unlikely green oasis of Riverside, Illinois, a small village that has continued to directly influence American landscapes and suburbs since the 1870s. Once farmland, the location provided a blank canvas for preeminent designers Fredrick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s manifestation of a truly democratic society. Olmsted’s Riverside details the village’s historical significance, harmony with nature, and its nearly 150-year impact on American suburbs today.

Cathy Jean Maloney explores how Riverside’s layout and design presaged today’s urban planning goals of walkability, green space, public transportation access, sustainability, and resiliency. Houses in Riverside are set back from the road, sidewalks meander along gently curving roads, and public green spaces abound. Maloney shows how Riverside’s leaders and residents struggled with stewardship of Olmsted’s ideals by balancing competing interests in suburban development and Chicago sprawl from the 1870s to the 2020s. She details in chronological chapters how the village adapted to tragedies such as the Great Fire of 1871 and the Panic of 1873, as well as advancements in transportation, local civic life, urban policy, and environmental thought, all while staying true to the framework inherited from Olmsted and Vaux.

Olmsted’s Riverside provides engaging examples of how citizen involvement can protect a community’s ideals. This richly illustrated volume combines landscape architecture, regional history, and urban design to show how audacious civic planning and thoughtful conservation can provide a model for future American suburbs.

Preț: 152.10 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 228

Preț estimativ în valută:

29.11€ • 30.24$ • 24.18£

29.11€ • 30.24$ • 24.18£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780809339525

ISBN-10: 0809339528

Pagini: 154

Ilustrații: 60

Dimensiuni: 254 x 203 x 8 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

ISBN-10: 0809339528

Pagini: 154

Ilustrații: 60

Dimensiuni: 254 x 203 x 8 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

Notă biografică

Cathy Jean Maloney is a landscape historian and author of five books on garden and environmental history, including World’s Fair Gardens: Shaping American Landscapes. For more than twenty years, Maloney served as senior editor of Chicagoland Gardening magazine. She also chaired the Landscape Advisory Commission in historic Riverside, Illinois, and spearheaded its certification as an arboretum. Maloney has appeared on numerous radio and TV shows, and teaches at the Morton Arboretum and the Chicago Botanic Garden while writing for national and regional publications.

Extras

INTRODUCTION

While on the phone with a landscape architect recently, I mentioned where I lived. “Riverside,” he mused. “That’s an interesting artifact.”

Artifact? Like a vestigial tail or a buggy whip? Something past its prime that belongs in a curiosity cabinet? To me, a Riverside resident of more than 30 years, the thriving, beautiful 150-plus-year old community glows with health and promise. This model suburb created by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in 1869 inspires today’s urban planners, landscape architects, and community designers. Equally important, Riverside’s long stewardship tradition to safeguard and invigorate this national treasure offers lessons to any community.

This is not just local boosterism. Olmsted’s design for Riverside, Illinois has outlasted technology changes, environmental disruption, demographic shifts, and tug-of-wars between public and private property rights. The Riverside General Plan of 1869 successfully pioneered subsequent master planning models and included walkability, integrated green space, mixed housing stock, transit-oriented-development, sense of community, quality architecture, and more elements to enhance quality of life. If everything old is new again, Riverside is the ultimate urban planning blueprint.

Olmsted and Vaux created Riverside, just outside of Chicago, at the behest of real estate investors. The plan incorporated the best ideas about working with nature to enhance residents’ overall well-being. Olmsted’s social reform philosophies including democratic ideals, healthful living, and moral uplifting underpinned the design. While pioneering, the design reflected the cumulative ideals of leading authors, reformers, and community planners of the day and of the years before. Still, Riverside was not created as a utopia, but as a profitable investment. Having seen the success of New York’s Central Park and other green spaces in raising nearby property values, Riverside’s investors hoped for sensational sales of their master-planned village fitted with an abundance of green spaces.

The Riverside plan boldly broke from previous grid-based city plans. The effect on the psyche is subtle: gently curved roads offer soothing vistas of abundant greenery and of the village’s namesake, the Des Plaines River. According to Olmsted scholar Charles Beveridge, “As a result of [Olmsted’s] own experience and wide reading, he concluded that the most powerful effect of scenery was one that worked by an unconscious process.” Now a National Historic Landmark village, Riverside’s classic design still evokes this intuitive embrace.

Scholarly articles and books routinely hail Riverside as a milestone in suburban planning, but then abruptly leave the story of the village in stasis at 1869. With so many traits of a desirable town plan, is it not worthwhile to examine how these features might be translated to other American communities? And, to learn how the design survived more or less intact, should we not consider the threats and opportunities to the plan as posed in the past fifteen decades? This book attempts to answer both of these questions. While I briefly mention the architecture in the village, there are other books that extol Riverside buildings by Frank Lloyd Wright, William Le Baron Jenney, Louis Sullivan, and other luminaries. My main emphasis is on the more fragile, and more ephemeral elements of the cultural landscape; the green spaces and how their usage changes over time.

Although Frederick Law Olmsted had already earned a reputation as a preeminent designer while planning Riverside, it was not until about 100 years later when serious scholarship on his work began with the Olmsted Papers Project in 1972. Two years prior, the National Park Service had designated Riverside as a National Historic Landmark. Thus, not only had nearly a century passed before Riverside received any preservation status, but in the fifty-plus years since, a host of new challenges confront the residents. The lessons from Riverside’s success and setbacks in stewardship over the decades will be useful to town planners and residents of any cherished community.

The push-pull of progress versus preservation plays out in several arenas. There are questions of the role of commerce (Riverside’s modest central business district) potentially competing with residential interests. Other persistent issues over the years have included differences in active or passive recreational use of green space, use of native or nonnative plantings, extent of outdoor signage, landscaping standards, use of quasi-public space, light pollution, noise abatement, river pollution and flooding, zoning issues, federal and state regulations, and more recently, the impact of climate change. Multi-generation residents know what has historically been done, new residents ask what else can be done, and everyone has the age-old, imponderable question, “What Would Olmsted Do?”

What would Olmsted do, a rhetorical query literally posed by modern-day residents, aims to imbue Olmsted’s philosophical ideals into any major decision affecting the village’s design. The goal is not necessarily to slavishly replicate the materials and exact elements of his plan onto a world that, in more than 150 years, has changed. Rather, it is to understand his thinking and, where possible, preserve for residents and visitors alike the thoughtful, naturalistic landscape design. To everyone’s bedevilment, Olmsted left no detailed planting plans for the village. Some residents have argued that, as a progressive thinker, Olmsted would adopt the latest technology or planting philosophy of today. There is appeal to this line of thought, until one considers that nearly all of America’s luminaries were also progressive thinkers: does this give the stewards of historic landmarks carte blanche to modify for today’s needs? Should, for example, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation convert the historic Monticello vineyards and vegetable gardens to an eco-friendly forest suitable for the Piedmont region? As is frequently the case, progress is pitted against preservation as a false choice.

Tradeoffs between environmental considerations and preservation concerns surface frequently in historic communities, including Riverside. Olmsted’s signature greenswards, large expanses of smooth lawn, for example, come under recent attack from ecologists who see turf as monocultures awash in polluting chemicals. Recently, a wonderful landscape architect prepared a plan for a small, but degraded green space in Riverside. To replace the turf and trees, the landscape architect proposed a more ecologically-friendly solution with an herbaceous layer of prairie plant natives. When asked if he could modify the design to a more traditional tree and grass combination, he remarked, “Oh, you mean, Riverside as a museum.” What is the correct response? Would prairie plants disrupt the overall harmony of trees and turf that tie together individual residences and public parks? Or, is it better to contribute more healthy habitats to Illinois, the “prairie state” where only one percent of prairies remain?

Riverside, like many areas in the American Midwest, is not immune to climate change. Heavy rainfalls throughout the Des Plaines River watershed area result in floods in Riverside. Presciently, Olmsted had reserved the riverbanks for greenery, never residential or commercial structures. Indeed, increased flooding events in recent years prompted a landscape change to one of Riverside’s most iconic vistas – the outlook over the river valley in an area called Swan Pond. Heretofore a pastoral view of greensward and trees, the Swan Pond manicured landscape was no longer sustainable since standing floodwater killed the grass and prevented regular mowing. After consulting with a landscape architect and the village’s Landscape Advisory Commission, the Village staff replaced part of the lawn in the most significant flood-prone area with wetland native plants. More recently, the entirety of Swan Pond was designated a managed natural area, with trial and error in use to gauge the effectiveness of the new habitat. Bioswales are also being introduced in other parts of Olmsted’s landscape.

Author and landscape architecture professor Richard Melznick proposes that historic landscape stewards find solutions more resilient to climate change. By identifying nonnegotiable aspects of an historic landscape, and allowing for potential substitutions in others, he offers a compromise. Suggesting a broader plant palette, for example, Melznick proposes, “. . .a more flexible understanding of what we mean by character-defining features, for example, especially when it comes to historic plant materials and plant communities.” Such is the continuum of choices that Riverside residents, and all stewards of historic landscapes, now face.

Climate change is the latest threat that dominates today’s headlines, and may be the most significant. Yet, Riverside has faced many other challenges during the past several decades that have tested the essence of Olmsted’s design. Flooding and river pollution have relentlessly plagued generations of Riversiders, with different causes and solutions each era. Riverside residents have targeted health issues, from mosquitoes to unleashed dogs, with ordinances or publicity campaigns. Debates over the optimal use of public land have caused lawsuits.

Yet, Riverside remains, very close to the original plan as laid out by Olmsted and Vaux after 150 years. The combination of stewardship and Olmsted’s design genius warrants a look at Riverside for inspiration in other communities. Olmsted’s Riverside is not an artifact, it is a living work of art, which may be appreciated for generations to come. We may never know what Olmsted would do. As stewards, we must develop basic principles to identify and preserve the true genius of place while adapting to the most pernicious of today’s challenges.

[end of excerpt]

While on the phone with a landscape architect recently, I mentioned where I lived. “Riverside,” he mused. “That’s an interesting artifact.”

Artifact? Like a vestigial tail or a buggy whip? Something past its prime that belongs in a curiosity cabinet? To me, a Riverside resident of more than 30 years, the thriving, beautiful 150-plus-year old community glows with health and promise. This model suburb created by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in 1869 inspires today’s urban planners, landscape architects, and community designers. Equally important, Riverside’s long stewardship tradition to safeguard and invigorate this national treasure offers lessons to any community.

This is not just local boosterism. Olmsted’s design for Riverside, Illinois has outlasted technology changes, environmental disruption, demographic shifts, and tug-of-wars between public and private property rights. The Riverside General Plan of 1869 successfully pioneered subsequent master planning models and included walkability, integrated green space, mixed housing stock, transit-oriented-development, sense of community, quality architecture, and more elements to enhance quality of life. If everything old is new again, Riverside is the ultimate urban planning blueprint.

Olmsted and Vaux created Riverside, just outside of Chicago, at the behest of real estate investors. The plan incorporated the best ideas about working with nature to enhance residents’ overall well-being. Olmsted’s social reform philosophies including democratic ideals, healthful living, and moral uplifting underpinned the design. While pioneering, the design reflected the cumulative ideals of leading authors, reformers, and community planners of the day and of the years before. Still, Riverside was not created as a utopia, but as a profitable investment. Having seen the success of New York’s Central Park and other green spaces in raising nearby property values, Riverside’s investors hoped for sensational sales of their master-planned village fitted with an abundance of green spaces.

The Riverside plan boldly broke from previous grid-based city plans. The effect on the psyche is subtle: gently curved roads offer soothing vistas of abundant greenery and of the village’s namesake, the Des Plaines River. According to Olmsted scholar Charles Beveridge, “As a result of [Olmsted’s] own experience and wide reading, he concluded that the most powerful effect of scenery was one that worked by an unconscious process.” Now a National Historic Landmark village, Riverside’s classic design still evokes this intuitive embrace.

Scholarly articles and books routinely hail Riverside as a milestone in suburban planning, but then abruptly leave the story of the village in stasis at 1869. With so many traits of a desirable town plan, is it not worthwhile to examine how these features might be translated to other American communities? And, to learn how the design survived more or less intact, should we not consider the threats and opportunities to the plan as posed in the past fifteen decades? This book attempts to answer both of these questions. While I briefly mention the architecture in the village, there are other books that extol Riverside buildings by Frank Lloyd Wright, William Le Baron Jenney, Louis Sullivan, and other luminaries. My main emphasis is on the more fragile, and more ephemeral elements of the cultural landscape; the green spaces and how their usage changes over time.

Although Frederick Law Olmsted had already earned a reputation as a preeminent designer while planning Riverside, it was not until about 100 years later when serious scholarship on his work began with the Olmsted Papers Project in 1972. Two years prior, the National Park Service had designated Riverside as a National Historic Landmark. Thus, not only had nearly a century passed before Riverside received any preservation status, but in the fifty-plus years since, a host of new challenges confront the residents. The lessons from Riverside’s success and setbacks in stewardship over the decades will be useful to town planners and residents of any cherished community.

The push-pull of progress versus preservation plays out in several arenas. There are questions of the role of commerce (Riverside’s modest central business district) potentially competing with residential interests. Other persistent issues over the years have included differences in active or passive recreational use of green space, use of native or nonnative plantings, extent of outdoor signage, landscaping standards, use of quasi-public space, light pollution, noise abatement, river pollution and flooding, zoning issues, federal and state regulations, and more recently, the impact of climate change. Multi-generation residents know what has historically been done, new residents ask what else can be done, and everyone has the age-old, imponderable question, “What Would Olmsted Do?”

What would Olmsted do, a rhetorical query literally posed by modern-day residents, aims to imbue Olmsted’s philosophical ideals into any major decision affecting the village’s design. The goal is not necessarily to slavishly replicate the materials and exact elements of his plan onto a world that, in more than 150 years, has changed. Rather, it is to understand his thinking and, where possible, preserve for residents and visitors alike the thoughtful, naturalistic landscape design. To everyone’s bedevilment, Olmsted left no detailed planting plans for the village. Some residents have argued that, as a progressive thinker, Olmsted would adopt the latest technology or planting philosophy of today. There is appeal to this line of thought, until one considers that nearly all of America’s luminaries were also progressive thinkers: does this give the stewards of historic landmarks carte blanche to modify for today’s needs? Should, for example, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation convert the historic Monticello vineyards and vegetable gardens to an eco-friendly forest suitable for the Piedmont region? As is frequently the case, progress is pitted against preservation as a false choice.

Tradeoffs between environmental considerations and preservation concerns surface frequently in historic communities, including Riverside. Olmsted’s signature greenswards, large expanses of smooth lawn, for example, come under recent attack from ecologists who see turf as monocultures awash in polluting chemicals. Recently, a wonderful landscape architect prepared a plan for a small, but degraded green space in Riverside. To replace the turf and trees, the landscape architect proposed a more ecologically-friendly solution with an herbaceous layer of prairie plant natives. When asked if he could modify the design to a more traditional tree and grass combination, he remarked, “Oh, you mean, Riverside as a museum.” What is the correct response? Would prairie plants disrupt the overall harmony of trees and turf that tie together individual residences and public parks? Or, is it better to contribute more healthy habitats to Illinois, the “prairie state” where only one percent of prairies remain?

Riverside, like many areas in the American Midwest, is not immune to climate change. Heavy rainfalls throughout the Des Plaines River watershed area result in floods in Riverside. Presciently, Olmsted had reserved the riverbanks for greenery, never residential or commercial structures. Indeed, increased flooding events in recent years prompted a landscape change to one of Riverside’s most iconic vistas – the outlook over the river valley in an area called Swan Pond. Heretofore a pastoral view of greensward and trees, the Swan Pond manicured landscape was no longer sustainable since standing floodwater killed the grass and prevented regular mowing. After consulting with a landscape architect and the village’s Landscape Advisory Commission, the Village staff replaced part of the lawn in the most significant flood-prone area with wetland native plants. More recently, the entirety of Swan Pond was designated a managed natural area, with trial and error in use to gauge the effectiveness of the new habitat. Bioswales are also being introduced in other parts of Olmsted’s landscape.

Author and landscape architecture professor Richard Melznick proposes that historic landscape stewards find solutions more resilient to climate change. By identifying nonnegotiable aspects of an historic landscape, and allowing for potential substitutions in others, he offers a compromise. Suggesting a broader plant palette, for example, Melznick proposes, “. . .a more flexible understanding of what we mean by character-defining features, for example, especially when it comes to historic plant materials and plant communities.” Such is the continuum of choices that Riverside residents, and all stewards of historic landscapes, now face.

Climate change is the latest threat that dominates today’s headlines, and may be the most significant. Yet, Riverside has faced many other challenges during the past several decades that have tested the essence of Olmsted’s design. Flooding and river pollution have relentlessly plagued generations of Riversiders, with different causes and solutions each era. Riverside residents have targeted health issues, from mosquitoes to unleashed dogs, with ordinances or publicity campaigns. Debates over the optimal use of public land have caused lawsuits.

Yet, Riverside remains, very close to the original plan as laid out by Olmsted and Vaux after 150 years. The combination of stewardship and Olmsted’s design genius warrants a look at Riverside for inspiration in other communities. Olmsted’s Riverside is not an artifact, it is a living work of art, which may be appreciated for generations to come. We may never know what Olmsted would do. As stewards, we must develop basic principles to identify and preserve the true genius of place while adapting to the most pernicious of today’s challenges.

[end of excerpt]

Cuprins

CONTENTS

Preface

Introduction

Chapter 1: Laying the Groundwork: Olmsted and Community Planning

Chapter 2: The Genius of the Plan, Job #607

Chapter 3: Off the Drawing Boards

Chapter 4: Progressives and Pollution (1880—1929)

Chapter 5: Depression through Atomic Age (1930—1969)

Chapter 6: Historic Landmark to New Millennium (1971—2000)

Chapter 7: The New Millennium (2000 to Present)

Chapter 8: The Next 150 Years

Acknowledgments

Bibliography

Index

Preface

Introduction

Chapter 1: Laying the Groundwork: Olmsted and Community Planning

Chapter 2: The Genius of the Plan, Job #607

Chapter 3: Off the Drawing Boards

Chapter 4: Progressives and Pollution (1880—1929)

Chapter 5: Depression through Atomic Age (1930—1969)

Chapter 6: Historic Landmark to New Millennium (1971—2000)

Chapter 7: The New Millennium (2000 to Present)

Chapter 8: The Next 150 Years

Acknowledgments

Bibliography

Index

Recenzii

“This is a book that needed to be written. Cathy Jean Maloney not only provides a complete, expert, and detailed history of the design and development of one of the country’s first suburbs, but also provides ample evidence that Riverside was and is an exemplar of the American suburban ideal.”—Malcolm Cairns, author of The Landscape Architecture Heritage of Illinois

“Maloney’s book offers a lively look at the past and future of Riverside, the model—and magical—suburb created by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in 1869. Using Riverside as an example, she acknowledges that historic preservation is not a static endeavor and explores the ways communities can safeguard and invigorate their historic designed treasures while adapting to modern challenges.”—Anne Neal Petri, president CEO, Olmsted Network

“Maloney helps us understand how a historically significant suburb designed by Frederick Law Olmsted learned to adapt to changing environmental, social, and cultural conditions while preserving historical integrity. The book will be of interest to urban historians, planners, and residents of places who seek to preserve what is good.”—Curt Winkle, associate professor emeritus of urban planning and policy, University of Illinois at Chicago

“Olmsted's Riverside is a case study in how one municipality has faced the struggles and strains of societal changes and worked to retain its initial nature—specifically its world-famous design by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. In addition, the book serves as an in-depth look at the ecology of a place where, for a century and a half, people have sought to have more of an interconnection with the natural world than most villages and cities provide. Maloney marshals her information well, seasons her pages with occasional pithy anecdotes and snappy quotes and keeps the pace moving. Her writing is energetic and far from stuffy. And the reader benefits greatly from Maloney’s obvious affection for the village and its design and her ability to describe how the village looks and feels, and how residents interact viscerally with the curving streets, vistas and other aspect of the design.”—Patrick T. Reardon, author of The Loop: The “L” Tracks That Shaped and Saved Chicago (SIU Press, 2020)

“Maloney’s book offers a lively look at the past and future of Riverside, the model—and magical—suburb created by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in 1869. Using Riverside as an example, she acknowledges that historic preservation is not a static endeavor and explores the ways communities can safeguard and invigorate their historic designed treasures while adapting to modern challenges.”—Anne Neal Petri, president CEO, Olmsted Network

“Maloney helps us understand how a historically significant suburb designed by Frederick Law Olmsted learned to adapt to changing environmental, social, and cultural conditions while preserving historical integrity. The book will be of interest to urban historians, planners, and residents of places who seek to preserve what is good.”—Curt Winkle, associate professor emeritus of urban planning and policy, University of Illinois at Chicago

“Olmsted's Riverside is a case study in how one municipality has faced the struggles and strains of societal changes and worked to retain its initial nature—specifically its world-famous design by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. In addition, the book serves as an in-depth look at the ecology of a place where, for a century and a half, people have sought to have more of an interconnection with the natural world than most villages and cities provide. Maloney marshals her information well, seasons her pages with occasional pithy anecdotes and snappy quotes and keeps the pace moving. Her writing is energetic and far from stuffy. And the reader benefits greatly from Maloney’s obvious affection for the village and its design and her ability to describe how the village looks and feels, and how residents interact viscerally with the curving streets, vistas and other aspect of the design.”—Patrick T. Reardon, author of The Loop: The “L” Tracks That Shaped and Saved Chicago (SIU Press, 2020)

Descriere

Olmsted's Riverside tells the story of the oasis of Riverside, Illinois, a Chicago suburb planned by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in 1869. The book describes the village's inception and details in four chronological chapters how Riverside adapted to tragedies and changes in public works technology and environmental thought.