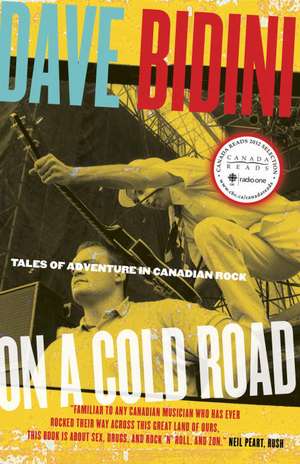

On a Cold Road: Tales of Adventure in Canadian Rock

Autor Dave Bidinien Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 1998

Bidini has played all across the country many times, in venues as far flung and unalike as Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto and the Royal Albert Hotel in Winnipeg. In 1996, when the Rheostatics opened for the Tragically Hip on their Trouble at the Henhouse tour, Bidini kept a diary. In On a Cold Road he weaves his colourful tales about that tour with revealing and hilarious anecdotes from the pioneers of Canadian rock - including BTO, Goddo, the Stampeders, Max Webster, Crowbar, the Guess Who, Triumph, Trooper, Bruce Cockburn, Gale Garnett, and Tommy Chong - whom Bidini later interviewed in an effort to compare their experiences with his. The result is an original, vivid, and unforgettable picture of what it has meant, for the last forty years, to be a rock musician in Canada.

Preț: 103.45 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 155

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.80€ • 20.72$ • 16.48£

19.80€ • 20.72$ • 16.48£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780771014567

ISBN-10: 0771014562

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 158 x 221 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

ISBN-10: 0771014562

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 158 x 221 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

Notă biografică

Author and musician Dave Bidini is the only person to have been nominated for a Gemini, Genie and Juno as well CBC's Canada Reads. A founding member of Rheostatics, he has written 10 books, including On a Cold Road, Tropic of Hockey, Around the World in 57 1/2 Gigs, and Home and Away. He has made two Gemini Award-nominated documentaries and his play, the Five Hole Stories, was staged by One Yellow Rabbit Performance Company, touring the country in 2008. His third book, Baseballissimo, is being developed for the screen by Jay Baruchel, and, in 2010, he won his third National Magazine Award, for "Travels in Narnia." He writes a weekly column for the Saturday Post and, in 2011, he published his latest book, Writing Gordon Lightfoot.

Extras

I was nothing but a pimply little question mark on the day my sister and I first walked into Ken Jones Music in Etobicoke. Sunlight streamed through the windows, dappling the guitars that hung behind the counter and bathing the small music shop at the back of the Westway Plaza in warm light. The store was cluttered with drums stacked on top of each other, keyboards leaning three deep against the walls, dusty racks of unread sheet music, long outdated band want-ads taped to the cash register, and ashtrays scattered across old chairs and window ledges. At the back of the store, young boys sat in tiny rooms plucking guitars through amplifiers that buzzed like heat bugs, the sound of their hammer-ons and finger-rolls and string-benders snaking out to where I stood, sucking it all in like sugar through a Pixie-Stik.

After our first taste of this place, my sister and I signed up for guitar lessons, which I grew to hate. My disdain might have had something to do with the fact that Cathy had mastered the basic chords and strumming technique before I’d grown my first finger callus. She out-licked me on “Kum Ba Yah,” “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore,” and “House of the Rising Sun,” which we debuted for our parents in our living room sitting on bridge table chairs behind music stands. I’d like to tell you that I rose to her challenge and went on to become a blurry-fingered virtuoso of the fretboard whose technique set the world’s pants on fire. But I did not.

Instead, I quit.

Cathy played her hand just right. My room was papered with an Aerosmith poster over my bed, 10cc above my night table, and Rush’s Farewell to Kings staring at me each night as I hit my pillow. Every other inch of the walls was pasted with photos culled from Hit Parader, Creem, and Circus magazines, or purchased at Flash Jack’s Head Shop, the scuzzy Yonge Street epicentre of high school stonerdom, where they sold roach clips and hash pipes and lurid pictures of Linda Ronstadt. These pictures of my favourite bands were testament to my desire to be like them, but they were also witness to my failure to do anything about it. I’d wander into my sister’s austere room – shockingly devoid of rock shrine-ography – and stare at her acoustic guitar, Mel Bay How-to-Play book, and music stand casually draped with belts, purses and other young-girl ephemera. In this display of coolness, Cathy seemed indifferent that she was better than me. My jealousy deepened. School ended. Summer passed. Winter descended. My sister played on.

But then a year later, mysteriously, she stopped. As soon as Cathy put away her guitar, I picked mine up again. I went back to Ken Jones Music to sign up for more lessons, still a damp patty of clay waiting to be palmed, but this time confident enough to look into the future and see someone other than who I was: a nervous child dressed in brown, ankle-riding cords and a maroon sweater that scratched like steel wool. No, this time I could see myself as a figure straight from my walls – a sparkling giant outfitted in electrically lit platform shoes and a spangly jumpsuit, flaunting a great bramble of chest hair, and topped by a frizzy afro and bug sunglasses.

I approached the counter, where an unclean fellow sat with his feet up, plucking a mandolin.

“I was wondering about guitar lessons,” I gulped.

“Do you play guitar, man?” asked the freak.

“No. Well, I did. But I’m not very good,” I said.

“Excellent,” he replied, strangely.

Stu looked like he’d just strode off a Three Dog Night album cover. He had that Jesus-as-folksinger look, thin-framed with a moustache and straggly beard. It was 1975. The first time I smelled pot, it was rising like steam off his flower-patched denim jacket. But while Stu was a prodigious stoner, he was a lot easier to understand than most of my teachers at school. He’d sit with me while I waited for my lesson with Ken and describe all the bands I’d never heard of whose music books he sold at the store – ZZ Top, the Eagles, Humble Pie, the James Gang. He told me about rigging a stage, setting up microphones, sound-checking, recording, tuning, and keeping your instrument in playable condition. He let me in on these mysteries as if he were spooling out paradigms from a lost language.

When a few friends and I finally got a band together, we set up in the store so that Stu could teach us the basic tenets of songwriting and arranging. We paid him with money given to us by our parents, who had parted with their hard-earned dollars even though they knew the money would be going to an indolent hippie who wore love beads and smoked skunk-weed from a water pipe. Stu took us through the looking glass, and we followed like Alice.

Our little combo was enthusiastic, if musically repugnant. We were four fourteen-year-olds playing the Triumph version of “Rocky Mountain Way” on out-of-tune instruments. Everybody took a solo, even our drummer, Mario Molinaro, who played so hard that he punched his sticks through his drumskins and shredded the hi-hats into shrapnel. But no matter how hellacious our din, Stu would listen patiently, bemused, and then show us what a bridge was. We were thrilled. Every now and then, his own group rehearsed in the store. We’d camp outside and listen to them play Led Zeppelin and Rush songs with three-tiered synthesizers, double-neck guitars, roto-tom drum terraces, disembowellingly loud bass guitars, and vocal mikes cabled through a Traynor P.A. To us it was like hearing the Stones at the Gardens. We vowed that we’d be good enough to have gear that real and a sound that big. Stu just tapped his head and said, “You will, you will,” then folded his hands in his lap.

Stu worked the front of the store, but the fellow whose name was on the place did most of the work. Ken Jones was a round, balding fellow who looked shockingly like Captain Kangaroo without the mendacious eyebrows. Ken sold me my first guitar, a white El Degas Stratocaster copy with a soft neck and a tone that was as warm and forgiving as a tire crunching glass. Ken showed me the basics out of the Mel Bay books, and soon I was putting two notes together, pretending to play “Rock and Roll Hoochie- Koo.” That Ken had the patience to take me this far was remarkable considering that he spent most of his time locked away in a closet-sized room teaching sweaty teenagers with breath like milk gone bad how to cop Eric Clapton licks or strum church hymns. He eventually passed me on to a local long-haired rock troll who tried teaching me Frank Marino, Joe Walsh, and Domenic Troiano riffs while his girlfriend sat cross-legged smoking in the corner. This often led to lead-guitar duels with him in which I placed a distant second. I was put off playing solos for the rest of my life, but Ken and Stu had already turned me on to music and there was no going back.

A few years after I left the store for other musical experiences, the Toronto Star wrote an article about the Rheostatics’ first gig at the Edge in February 1980. We were seventeen years old at the time and had to get a special liquor permit to play in the club. About fifty kids from high school came to see us play, and when we finished, the band we were opening for pleaded with us to get our friends to stay. But it was a school night. The Star found all of this interminably cute and dispatched a reporter to interview and photograph us on the bleachers of a high-school football field. I owe it to my mom for calling them and suggesting the idea in the first place. It was the first time I ever saw myself in print, and it was a shock. In the photo, I’m wearing blue trousers, a white striped blazer, and a T-shirt with an exclamation mark on it. Even though I’m sporting my most expensive haircut to date – thirty dollars at Super Cutz in Sherway Gardens – my head still looks like a luge helmet.

Ken Jones posted the clipping in his shop. He drew an arrow pointing to me and wrote, “I taught him!” on it. He didn’t do it because he had any intuition that we would dent the mug of Canadian rock, or grow up to dazzle industry captains or play sold-out concerts in hockey rinks or take champagne baths in rooms wallpapered with money. It was because of one gig.

One.

Three dollars. Tuesday night.

The Edge.

Sixteen years, handfuls of tours, walls of faces, miles of strings and cables, thickets of magnetic and electrical tape, lakes of beer, numberless clubhouse sandwiches, and six hundred gigs later, we were asked to do a national tour with the Tragically Hip in the winter of 1996 to support their Trouble at the Henhouse album. The biggest tour by a Canadian band in the history of music in Canada. It would put the Rheostatics in front of almost half a million people and finally give us a chance to play our music to the mass audience that till then had eluded us. Since our inaugural gig at the Edge in 1980, we’d gone through many changes in sound and had suffered the loss of our drummer of fourteen years, Dave Clark, who quit the band sixteen months before our tour. People like Stu and Ken and a million others had floated across those years, and as I set out to write down my experiences about being on the road, I found myself thinking not only about them, but also about the bands and musicians whose songs I’d heard on the radio as a kid, and whose bravura had founded the musical culture in which I now lived and explored.

I decided to track down these figures from my past. I wanted to understand, through them, the anatomy of making music in a country noted more for space and snow than for money or people. I was fully aware of the struggle it takes to sustain a musical career in Canada (I was painfully conscious that a small number of consumers supported Canadian bands – 19 per cent of total sales – and that our scant population meant that musicians shared the same audience in ten cities across the country), but I knew very little about the artists themselves. It became important to me to know what it was like for the early bands, the first to leave their home towns hauling P.A. systems and glitter balls, chasing down one-nighters in towns that barely existed. They’d established the east-west route that every Canadian group now travelled, and more than likely took for granted. Without their perseverance, neither we nor the Hip would have had reason to exist, let alone to light out for the coast, let alone to write this book.

After our first taste of this place, my sister and I signed up for guitar lessons, which I grew to hate. My disdain might have had something to do with the fact that Cathy had mastered the basic chords and strumming technique before I’d grown my first finger callus. She out-licked me on “Kum Ba Yah,” “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore,” and “House of the Rising Sun,” which we debuted for our parents in our living room sitting on bridge table chairs behind music stands. I’d like to tell you that I rose to her challenge and went on to become a blurry-fingered virtuoso of the fretboard whose technique set the world’s pants on fire. But I did not.

Instead, I quit.

Cathy played her hand just right. My room was papered with an Aerosmith poster over my bed, 10cc above my night table, and Rush’s Farewell to Kings staring at me each night as I hit my pillow. Every other inch of the walls was pasted with photos culled from Hit Parader, Creem, and Circus magazines, or purchased at Flash Jack’s Head Shop, the scuzzy Yonge Street epicentre of high school stonerdom, where they sold roach clips and hash pipes and lurid pictures of Linda Ronstadt. These pictures of my favourite bands were testament to my desire to be like them, but they were also witness to my failure to do anything about it. I’d wander into my sister’s austere room – shockingly devoid of rock shrine-ography – and stare at her acoustic guitar, Mel Bay How-to-Play book, and music stand casually draped with belts, purses and other young-girl ephemera. In this display of coolness, Cathy seemed indifferent that she was better than me. My jealousy deepened. School ended. Summer passed. Winter descended. My sister played on.

But then a year later, mysteriously, she stopped. As soon as Cathy put away her guitar, I picked mine up again. I went back to Ken Jones Music to sign up for more lessons, still a damp patty of clay waiting to be palmed, but this time confident enough to look into the future and see someone other than who I was: a nervous child dressed in brown, ankle-riding cords and a maroon sweater that scratched like steel wool. No, this time I could see myself as a figure straight from my walls – a sparkling giant outfitted in electrically lit platform shoes and a spangly jumpsuit, flaunting a great bramble of chest hair, and topped by a frizzy afro and bug sunglasses.

I approached the counter, where an unclean fellow sat with his feet up, plucking a mandolin.

“I was wondering about guitar lessons,” I gulped.

“Do you play guitar, man?” asked the freak.

“No. Well, I did. But I’m not very good,” I said.

“Excellent,” he replied, strangely.

Stu looked like he’d just strode off a Three Dog Night album cover. He had that Jesus-as-folksinger look, thin-framed with a moustache and straggly beard. It was 1975. The first time I smelled pot, it was rising like steam off his flower-patched denim jacket. But while Stu was a prodigious stoner, he was a lot easier to understand than most of my teachers at school. He’d sit with me while I waited for my lesson with Ken and describe all the bands I’d never heard of whose music books he sold at the store – ZZ Top, the Eagles, Humble Pie, the James Gang. He told me about rigging a stage, setting up microphones, sound-checking, recording, tuning, and keeping your instrument in playable condition. He let me in on these mysteries as if he were spooling out paradigms from a lost language.

When a few friends and I finally got a band together, we set up in the store so that Stu could teach us the basic tenets of songwriting and arranging. We paid him with money given to us by our parents, who had parted with their hard-earned dollars even though they knew the money would be going to an indolent hippie who wore love beads and smoked skunk-weed from a water pipe. Stu took us through the looking glass, and we followed like Alice.

Our little combo was enthusiastic, if musically repugnant. We were four fourteen-year-olds playing the Triumph version of “Rocky Mountain Way” on out-of-tune instruments. Everybody took a solo, even our drummer, Mario Molinaro, who played so hard that he punched his sticks through his drumskins and shredded the hi-hats into shrapnel. But no matter how hellacious our din, Stu would listen patiently, bemused, and then show us what a bridge was. We were thrilled. Every now and then, his own group rehearsed in the store. We’d camp outside and listen to them play Led Zeppelin and Rush songs with three-tiered synthesizers, double-neck guitars, roto-tom drum terraces, disembowellingly loud bass guitars, and vocal mikes cabled through a Traynor P.A. To us it was like hearing the Stones at the Gardens. We vowed that we’d be good enough to have gear that real and a sound that big. Stu just tapped his head and said, “You will, you will,” then folded his hands in his lap.

Stu worked the front of the store, but the fellow whose name was on the place did most of the work. Ken Jones was a round, balding fellow who looked shockingly like Captain Kangaroo without the mendacious eyebrows. Ken sold me my first guitar, a white El Degas Stratocaster copy with a soft neck and a tone that was as warm and forgiving as a tire crunching glass. Ken showed me the basics out of the Mel Bay books, and soon I was putting two notes together, pretending to play “Rock and Roll Hoochie- Koo.” That Ken had the patience to take me this far was remarkable considering that he spent most of his time locked away in a closet-sized room teaching sweaty teenagers with breath like milk gone bad how to cop Eric Clapton licks or strum church hymns. He eventually passed me on to a local long-haired rock troll who tried teaching me Frank Marino, Joe Walsh, and Domenic Troiano riffs while his girlfriend sat cross-legged smoking in the corner. This often led to lead-guitar duels with him in which I placed a distant second. I was put off playing solos for the rest of my life, but Ken and Stu had already turned me on to music and there was no going back.

A few years after I left the store for other musical experiences, the Toronto Star wrote an article about the Rheostatics’ first gig at the Edge in February 1980. We were seventeen years old at the time and had to get a special liquor permit to play in the club. About fifty kids from high school came to see us play, and when we finished, the band we were opening for pleaded with us to get our friends to stay. But it was a school night. The Star found all of this interminably cute and dispatched a reporter to interview and photograph us on the bleachers of a high-school football field. I owe it to my mom for calling them and suggesting the idea in the first place. It was the first time I ever saw myself in print, and it was a shock. In the photo, I’m wearing blue trousers, a white striped blazer, and a T-shirt with an exclamation mark on it. Even though I’m sporting my most expensive haircut to date – thirty dollars at Super Cutz in Sherway Gardens – my head still looks like a luge helmet.

Ken Jones posted the clipping in his shop. He drew an arrow pointing to me and wrote, “I taught him!” on it. He didn’t do it because he had any intuition that we would dent the mug of Canadian rock, or grow up to dazzle industry captains or play sold-out concerts in hockey rinks or take champagne baths in rooms wallpapered with money. It was because of one gig.

One.

Three dollars. Tuesday night.

The Edge.

Sixteen years, handfuls of tours, walls of faces, miles of strings and cables, thickets of magnetic and electrical tape, lakes of beer, numberless clubhouse sandwiches, and six hundred gigs later, we were asked to do a national tour with the Tragically Hip in the winter of 1996 to support their Trouble at the Henhouse album. The biggest tour by a Canadian band in the history of music in Canada. It would put the Rheostatics in front of almost half a million people and finally give us a chance to play our music to the mass audience that till then had eluded us. Since our inaugural gig at the Edge in 1980, we’d gone through many changes in sound and had suffered the loss of our drummer of fourteen years, Dave Clark, who quit the band sixteen months before our tour. People like Stu and Ken and a million others had floated across those years, and as I set out to write down my experiences about being on the road, I found myself thinking not only about them, but also about the bands and musicians whose songs I’d heard on the radio as a kid, and whose bravura had founded the musical culture in which I now lived and explored.

I decided to track down these figures from my past. I wanted to understand, through them, the anatomy of making music in a country noted more for space and snow than for money or people. I was fully aware of the struggle it takes to sustain a musical career in Canada (I was painfully conscious that a small number of consumers supported Canadian bands – 19 per cent of total sales – and that our scant population meant that musicians shared the same audience in ten cities across the country), but I knew very little about the artists themselves. It became important to me to know what it was like for the early bands, the first to leave their home towns hauling P.A. systems and glitter balls, chasing down one-nighters in towns that barely existed. They’d established the east-west route that every Canadian group now travelled, and more than likely took for granted. Without their perseverance, neither we nor the Hip would have had reason to exist, let alone to light out for the coast, let alone to write this book.