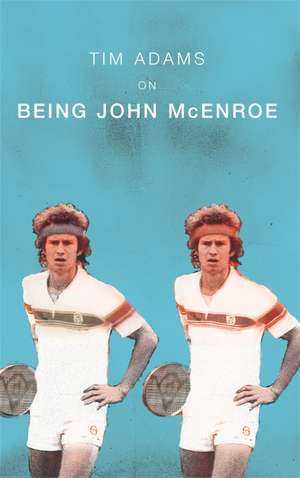

On Being John McEnroe

Autor Tim Adamsen Limba Engleză Paperback – 3 iun 2004

The greatest sports stars characterize their times. They also help to tell us who we are. John McEnroe, at his best and worst, encapsulated the story of the eighties. His improvised quest for tennis perfection and his inability to find a way to grow up dramatized the volatile self-absorption of a generation. His matches were open therapy sessions and they allowed us all to be armchair shrinks.

Tim Adams sets out to explore what it might have meant to be John McEnroe during those times and to define exactly what it is we want from our sporting heroes: how we require them to play out our own dramas; how the best of them provide an intensity that we can measure our own lives by.

Talking to McEnroe, his friends and rivals, and drawing on a range of references, Tim Adams presents a book that is both a portrait of the most colourful player ever to pick up a racket and an original study of the idea of sporting obsession.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 80.19 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 120

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.34€ • 16.02$ • 12.70£

15.34€ • 16.02$ • 12.70£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Livrare express 01-07 martie pentru 13.08 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780224069625

ISBN-10: 0224069624

Pagini: 160

Dimensiuni: 105 x 166 x 11 mm

Greutate: 0.08 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

ISBN-10: 0224069624

Pagini: 160

Dimensiuni: 105 x 166 x 11 mm

Greutate: 0.08 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

Recenzii

“On Being John McEnroe is great . . . it’s witty and smart, and has ideas about sport that don’t strain for significance . . . My favorite McEnroe tirade, one I hadn’t heard before: ‘I’m so disgusting you shouldn’t watch. Everybody leave!’” —Nick Hornby

“Full of pleasures. Adams writes beautifully, is strong on social context, and is sensible about psychological theorizing. Best of all, he does a fine job in re-creating those wonderful encounters between Mac and Borg, Mac and the umpires, Mac and the All-England Club establishment, Mac and the world.” —The Sunday Times

“We got the official version of the life . . . from [You Cannot Be Serious,] McEnroe’s punchy, if coy in places, autobiography. Now here’s the theory—nine deft chapters and an epilogue in which Adams reflects on the nature of the fires flickering and flaring in McEnroe and the ways in which he defined and embodied his time.” —The Daily Telegraph

“A brilliantly insightful essay about a tormented genius who found in tennis an expressionist art form.” —The Independent

“[On Being John McEnroe is] terrific. On one level, it’s about the author’s fascination with a tennis player. But it’s much more than this; it’s a book about how the world has changed in our lifetime. . . . This is a wonderful essay on individuality, as well as a cracking book about tennis.” —The New Statesman

From the Hardcover edition.

“Full of pleasures. Adams writes beautifully, is strong on social context, and is sensible about psychological theorizing. Best of all, he does a fine job in re-creating those wonderful encounters between Mac and Borg, Mac and the umpires, Mac and the All-England Club establishment, Mac and the world.” —The Sunday Times

“We got the official version of the life . . . from [You Cannot Be Serious,] McEnroe’s punchy, if coy in places, autobiography. Now here’s the theory—nine deft chapters and an epilogue in which Adams reflects on the nature of the fires flickering and flaring in McEnroe and the ways in which he defined and embodied his time.” —The Daily Telegraph

“A brilliantly insightful essay about a tormented genius who found in tennis an expressionist art form.” —The Independent

“[On Being John McEnroe is] terrific. On one level, it’s about the author’s fascination with a tennis player. But it’s much more than this; it’s a book about how the world has changed in our lifetime. . . . This is a wonderful essay on individuality, as well as a cracking book about tennis.” —The New Statesman

From the Hardcover edition.

Notă biografică

Tim Adams has been an editor at Granta and literary editor of the Observer, where he now writes full-time. An occasional tennis correspondent and scratchy parks player, he once lost in straight sets to Martin Amis and served a whole game of double faults to Annabel Croft. He lives in London.

Extras

Chapter One: Perfect Day

In the summer of 1983, I queued up for most of a drizzly night in south London to watch John McEnroe play the unseeded American Bill Scanlon in the last sixteen at Wimbledon. To pass the time in the queue I’d brought a couple of books to read. One of them was J. D. Salinger’s Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters. I’d not long before read The Catcher in the Rye, and had developed a carefully worked out theory (I seem to remember) that McEnroe was, in fact, a latter-day Holden Caulfield, unable and unwilling to grow up, full of complicated genius and unresolved conflict, constantly railing against the phonies—dozing linesmen, tournament organisers with walkie-talkies—in authority. I’d brought the novella along therefore, I imagine, in a dubious kind of private homage—my only defence is that I was seventeen—or at least in the pretentious belief that it would make an appropriate preface to the next day’s match.

In any case, when I was reading it in the grey dawn halfway down Somerset Road, a particular passage stuck in my head. Salinger was struggling to describe the idea of perfection in one of his character’s lives, and the closest he could get to it was a tennis match. Perfection was, he suggested, a feeling like “someone you love coming up onto the porch, grinning after three hard sets of victorious tennis, to ask you if you saw the last shot he made.”

It undoubtedly seemed to me then, and it still just about seems to me now, that this was the kind of feeling that John McEnroe was always restless for, and sometimes able to communicate in his game: a kind of instinctive euphoria. He’d found it a few times in his matches against Bjorn Borg, but at the age of twenty-four, after his great rival had retired prematurely, it already looked like he was struggling to summon that kind of heightened sense. As a result he was looking more angry and disconsolate than ever.

Certainly that was the case on that heavily clouded afternoon against the prosaic Scanlon. McEnroe won somewhat disdainfully in straight sets, using all the angles, berating himself and the officials, scratching his head, tugging at the shoulders of his shirt, having a great deal of trouble at changeovers with the lacing of his shoes, searching all the time for something like the appropriate sense of occasion. He had never, of course, looked entirely comfortable on a tennis court, constantly vigilant as he was for the one thing that was ruining it all for him that day—a spectator with a cough, a television microphone—but all through that year’s tournament, which he won by beating the starstruck Kiwi Chris Lewis in a hopelessly one-sided final, he played as if something was absent from his life.

I had a sense then, watching him desperately try to find some kind of self-respect, that the thing which was missing, the thing that had been taken away from him, and from the rest of us, was the real shot at perfection or fulfillment which his games against Borg had offered. He had needed something in his rival to make himself feel whole.

Nearly twenty years later, when I asked him about this during an interview in Chicago, he agreed with the interpretation. “In 1981 when I beat Borg in the Wimbledon finals and then beat him at the US Open, suddenly, out of nowhere, he stopped playing the major events,” he said. “To me it was devastating, if that’s the word. . . . I certainly got very empty after that because it had been so very exciting up to that point. Of course, there were other great challenges—Ivan Lendl and Jimmy Connors—but it was so natural with Borg. Our personalities were so different, the way we played was so different, nothing ever needed to be said.”

Great tennis players, like great chess players or great boxers, cannot exist in isolation: they require a rivalry, an equal, to allow them to discover what they might be capable of. When Andre Agassi returned to the game after his self-imposed break “at the buffet table” in his mid-twenties, Pete Sampras, his nemesis, sent him a heartfelt note expressing relief that he was back. McEnroe tried, every time he met Borg, to persuade him to return to tennis, but he never really got even an explanation for the Swede’s retirement.

When I asked him how he thought their matches would have gone had Borg not retired, he thought for a moment before suggesting that he believed they would both have got better and better as players and, probably, as people, “and that might have been something to see. . . . As it was I found myself lost a bit. I pulled it together, and played probably my greatest tennis in 1984 [the year he dismantled Connors in the Wimbledon final, making only three unforced errors], but even at the end of that year I felt not at all happy. There was this void,” he said, “and I always felt it was up to me in a sense to manufacture my own intensity thereafter.”

Chapter Two: Self 1 and Self 2

John McEnroe had first seen Bjorn Borg play when he was working as a ball boy at the US Open at Forest Hills in 1971. The Swede had already, at fifteen, begun to make a name for himself and collect a hormonal following of schoolgirl fans. Though only three years his senior, to McEnroe—and no doubt to the schoolgirls—Borg looked very much like a grown-up, a state to which McEnroe himself subsequently struggled to aspire. (Like Richie in Wes Anderson’s film The Royal Tenenbaums, McEnroe was in part entranced by the brevity of Borg’s kit: “the Fila outfit, the tight shirts and short shorts . . . I loved that stuff!”). He later had, alongside those of Rod Laver and Farrah Fawcett, a poster of Borg on his bedroom wall.

By the time they got to play each other, Borg was already established as the world’s number one. He had won three Wimbledons and three French Opens; he was living as a tax exile in Monte Carlo; and he had long silenced the adolescent screams of most of his following with the almost pathological reserve and concentration he displayed when playing: there seemed no way to get to him.

McEnroe, though, was determined to break through that mental armoury. He and Borg first met on court, appropriately enough, in Stockholm in 1978, at Borg’s home tournament, in front of the Swedish royal family, who had come to observe the smooth progress of their champion. McEnroe, never a great respecter of form or expectation, beat Borg, and his legend, 6—3, 6—4. It was this victory more than anything—more than his spectacular debut Wimbledon of 1977, when he had reached the semifinal as an eighteen-year-old qualifier and taken a set off Jimmy Connors—that convinced him he could achieve something in the game: “If I could beat Borg,” he said, later, “then I knew I could beat all the others.”

For Borg—who won only 7 points on McEnroe’s serve in that match—that initial meeting held a particular significance, too. It was the first time he had ever been beaten on the tour by someone younger than himself—the first hint, perhaps, of the knowledge that eventually comes to all prodigies: that he, too, would grow old.

To understand anything about McEnroe, it seems first necessary to examine his relationship with Borg. Well before their monumental struggle in the Wimbledon final of 1980, McEnroe had resolved both to establish the Swede as his greatest rival and to eclipse him. Most gifted young tennis players hope to get into the top ten or the top five, but McEnroe always believed he could be number one. With this in mind, he first worked extremely hard to be accepted as a peer of Borg’s, both on and off the court. By the time of their Wimbledon meeting in 1980, he was getting closer to his hero. He had beaten Borg twice more, but the Swede was up 4—3 in matches. They had, too, been partying together along with their mutual friend and master of revels Vitas Gerulaitis.

Borg could see McEnroe coming. In a pictorial autobiography published the week before Wimbledon, Borg examined the contenders for his number one position in 1980: “Jimmy Connors has been my most intense rival for six years,” he wrote. “But at the moment, John McEnroe has the game to give both Jimmy and me sleepless nights. His style is flexible while Jimmy’s is rigid . . . but the fury of a McEnroe/Borg rivalry has not yet had a chance to boil over. It’s still simmering.”

At the same time, McEnroe conceded that “sure, we act differently on court. Once in New Orleans when I went berserk over a call he gently waved his palms up and down to calm me. When we play, the match is always going to be interesting, because of our contrasting styles, with me trying to rush the net and him staying in the backcourt. Sometimes when he and Connors play it’s dull because they both stay in backcourt until someone misses. The most satisfying place for me to beat Bjorn? The French Championships in Paris on clay over five sets.”

Like Muhammad Ali and George Foreman, or Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer, both McEnroe and Borg seemed immediately to see in the other qualities and philosophies that they lacked in themselves, both as players and people. Perhaps unlike those other rivals, though, they each seemed to love the other for his difference. For Borg, McEnroe possessed spontaneity and instinct and was a source of constant surprise. “It sounds strange,” he noted, “but he has more touch than Nastase. He is a master of the unexpected. I can never anticipate his shots.”

For McEnroe, Borg had patience and calm and something like grace. Most of all, he loved the “cleanness” of Borg as an opponent, compared to his own psychological mess. “Borg accepted me,” McEnroe suggests, as if that is all he ever wanted. “There was a level of respect there that I never really reached with anyone else. It was as if he were saying to me, look, we are hitting a tennis ball over the net and this is a pretty damn good way to make a living. And here I was going crazy and thinking he was about to call me an ass. It was beautiful in that way.”

Anyone who has played tennis at any level knows that on court is one of the few places where, generally speaking, you are allowed to talk to yourself, even if it is only to say “C’mmmmmmmooonnnnn!!!” (like Lleyton Hewitt), or “C’mon!” (like Tim Henman). At the time that McEnroe’s game was forming, sports psychology was becoming big business. Few players took a therapist on the road with them, as many do now, but analysis was in the culture, and it was only a matter of time before it became applied to tennis, which, in its balance between extreme action and contemplative inaction, and its relentless examination of the individual, is perhaps the most mentally fraught of

sports.

Many coaches sought to employ the techniques of therapy to their players’ advantage, but few were as successful as W. Timothy Gallwey, who, at the age of fifteen, had missed a heartbreakingly easy volley for match point in the National Junior Tennis Championships in America and always wondered why. In 1976, the year of Borg’s first Wimbledon triumph, Gallwey published a little book called The Inner Game of Tennis, which was pitched, in the spirit of the time, as being somewhere between Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance and How to Win Friends and Influence People. In it he observed that when most people played the game they routinely divided themselves in their heads and, typically, one half of their self railed at the other half, the half that was serving double faults and fluffing volleys.

“Imagine that instead of being two parts of the same person,” Gallwey wrote, “Self 1 and Self 2 are two separate persons. How would you characterise their relationship after witnessing the following conversation between them? The player on court is trying to make a stroke improvement. ‘Okay, dammit, keep your stupid wrist firm,’ he orders. Then as ball after ball comes over the net, Self 1 reminds Self 2, ‘Keep it firm. Keep it firm. Keep it firm!’ Monotonous? Think how Self 2 must feel! It seems as though Self 1 doesn’t think Self 2 hears well, or has a short memory, or is stupid. The truth is, of course, that Self 2, which includes the unconscious mind and nervous system, hears everything, never forgets anything, and is anything but stupid.”

To achieve any kind of success, in tennis, or in life, Gallwey went on to suggest, Self 1, the conscious, nagging, neurotic mind, had to be prepared to get off court. If tennis were taken as a paradigm for life in general, and in particular that kind of modern life which threw pace and spin at you in equal measure, then “the most indispensable tool is the ability to remain calm in the midst of rapid and unsettling changes. The person who will best survive in the present age is the one Kipling described as he who can keep his head while all about are losing theirs. . . .”

In writing this, Gallwey might have been describing Borg, who was almost unique among tennis players in managing, or at least appearing to manage, to take the emotional, self-doubting side of his mind entirely out of his game. In 1980 Borg was insisting, also along with Kipling (whose poem “If” greeted players in the Wimbledon locker room) that “once a match is over, it’s over. I don’t carry either the pain or the glory with me.”

Gallwey would not, however, have known where to begin with McEnroe. The psychologist argued, employing a new phrase, that “ ‘freaking out’ is a general term used for an upset mind. For example, it describes what happens in the mind of many tennis players just after they have hit a shallow lob, or while preparing to serve on match point with the memory of past faults rushing through their minds. Freaking out is [also] what stockbrokers do when the market begins to plunge; or what some parents do when their child has not returned from a date on time. . . . When action is born in worry and self-doubt, it is usually inappropriate and often too late to be effective.”

If Borg sought to remove the fretting of his conscious mind from play, to let habit and faith in his physical strength and skill take over, McEnroe seemed unable and often unwilling to quiet the voices in his head for even a moment. Every shot he played, even his soft-handed instinctive volleying, appeared, to some degree, to have been born out of a titanic internal struggle with “worry and self-doubt.” His face and body language constantly betrayed the fact that he wanted to question the integrity of every ball he went for, every move he took, and every decision he or anyone else made on court.

From the Hardcover edition.

In the summer of 1983, I queued up for most of a drizzly night in south London to watch John McEnroe play the unseeded American Bill Scanlon in the last sixteen at Wimbledon. To pass the time in the queue I’d brought a couple of books to read. One of them was J. D. Salinger’s Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters. I’d not long before read The Catcher in the Rye, and had developed a carefully worked out theory (I seem to remember) that McEnroe was, in fact, a latter-day Holden Caulfield, unable and unwilling to grow up, full of complicated genius and unresolved conflict, constantly railing against the phonies—dozing linesmen, tournament organisers with walkie-talkies—in authority. I’d brought the novella along therefore, I imagine, in a dubious kind of private homage—my only defence is that I was seventeen—or at least in the pretentious belief that it would make an appropriate preface to the next day’s match.

In any case, when I was reading it in the grey dawn halfway down Somerset Road, a particular passage stuck in my head. Salinger was struggling to describe the idea of perfection in one of his character’s lives, and the closest he could get to it was a tennis match. Perfection was, he suggested, a feeling like “someone you love coming up onto the porch, grinning after three hard sets of victorious tennis, to ask you if you saw the last shot he made.”

It undoubtedly seemed to me then, and it still just about seems to me now, that this was the kind of feeling that John McEnroe was always restless for, and sometimes able to communicate in his game: a kind of instinctive euphoria. He’d found it a few times in his matches against Bjorn Borg, but at the age of twenty-four, after his great rival had retired prematurely, it already looked like he was struggling to summon that kind of heightened sense. As a result he was looking more angry and disconsolate than ever.

Certainly that was the case on that heavily clouded afternoon against the prosaic Scanlon. McEnroe won somewhat disdainfully in straight sets, using all the angles, berating himself and the officials, scratching his head, tugging at the shoulders of his shirt, having a great deal of trouble at changeovers with the lacing of his shoes, searching all the time for something like the appropriate sense of occasion. He had never, of course, looked entirely comfortable on a tennis court, constantly vigilant as he was for the one thing that was ruining it all for him that day—a spectator with a cough, a television microphone—but all through that year’s tournament, which he won by beating the starstruck Kiwi Chris Lewis in a hopelessly one-sided final, he played as if something was absent from his life.

I had a sense then, watching him desperately try to find some kind of self-respect, that the thing which was missing, the thing that had been taken away from him, and from the rest of us, was the real shot at perfection or fulfillment which his games against Borg had offered. He had needed something in his rival to make himself feel whole.

Nearly twenty years later, when I asked him about this during an interview in Chicago, he agreed with the interpretation. “In 1981 when I beat Borg in the Wimbledon finals and then beat him at the US Open, suddenly, out of nowhere, he stopped playing the major events,” he said. “To me it was devastating, if that’s the word. . . . I certainly got very empty after that because it had been so very exciting up to that point. Of course, there were other great challenges—Ivan Lendl and Jimmy Connors—but it was so natural with Borg. Our personalities were so different, the way we played was so different, nothing ever needed to be said.”

Great tennis players, like great chess players or great boxers, cannot exist in isolation: they require a rivalry, an equal, to allow them to discover what they might be capable of. When Andre Agassi returned to the game after his self-imposed break “at the buffet table” in his mid-twenties, Pete Sampras, his nemesis, sent him a heartfelt note expressing relief that he was back. McEnroe tried, every time he met Borg, to persuade him to return to tennis, but he never really got even an explanation for the Swede’s retirement.

When I asked him how he thought their matches would have gone had Borg not retired, he thought for a moment before suggesting that he believed they would both have got better and better as players and, probably, as people, “and that might have been something to see. . . . As it was I found myself lost a bit. I pulled it together, and played probably my greatest tennis in 1984 [the year he dismantled Connors in the Wimbledon final, making only three unforced errors], but even at the end of that year I felt not at all happy. There was this void,” he said, “and I always felt it was up to me in a sense to manufacture my own intensity thereafter.”

Chapter Two: Self 1 and Self 2

John McEnroe had first seen Bjorn Borg play when he was working as a ball boy at the US Open at Forest Hills in 1971. The Swede had already, at fifteen, begun to make a name for himself and collect a hormonal following of schoolgirl fans. Though only three years his senior, to McEnroe—and no doubt to the schoolgirls—Borg looked very much like a grown-up, a state to which McEnroe himself subsequently struggled to aspire. (Like Richie in Wes Anderson’s film The Royal Tenenbaums, McEnroe was in part entranced by the brevity of Borg’s kit: “the Fila outfit, the tight shirts and short shorts . . . I loved that stuff!”). He later had, alongside those of Rod Laver and Farrah Fawcett, a poster of Borg on his bedroom wall.

By the time they got to play each other, Borg was already established as the world’s number one. He had won three Wimbledons and three French Opens; he was living as a tax exile in Monte Carlo; and he had long silenced the adolescent screams of most of his following with the almost pathological reserve and concentration he displayed when playing: there seemed no way to get to him.

McEnroe, though, was determined to break through that mental armoury. He and Borg first met on court, appropriately enough, in Stockholm in 1978, at Borg’s home tournament, in front of the Swedish royal family, who had come to observe the smooth progress of their champion. McEnroe, never a great respecter of form or expectation, beat Borg, and his legend, 6—3, 6—4. It was this victory more than anything—more than his spectacular debut Wimbledon of 1977, when he had reached the semifinal as an eighteen-year-old qualifier and taken a set off Jimmy Connors—that convinced him he could achieve something in the game: “If I could beat Borg,” he said, later, “then I knew I could beat all the others.”

For Borg—who won only 7 points on McEnroe’s serve in that match—that initial meeting held a particular significance, too. It was the first time he had ever been beaten on the tour by someone younger than himself—the first hint, perhaps, of the knowledge that eventually comes to all prodigies: that he, too, would grow old.

To understand anything about McEnroe, it seems first necessary to examine his relationship with Borg. Well before their monumental struggle in the Wimbledon final of 1980, McEnroe had resolved both to establish the Swede as his greatest rival and to eclipse him. Most gifted young tennis players hope to get into the top ten or the top five, but McEnroe always believed he could be number one. With this in mind, he first worked extremely hard to be accepted as a peer of Borg’s, both on and off the court. By the time of their Wimbledon meeting in 1980, he was getting closer to his hero. He had beaten Borg twice more, but the Swede was up 4—3 in matches. They had, too, been partying together along with their mutual friend and master of revels Vitas Gerulaitis.

Borg could see McEnroe coming. In a pictorial autobiography published the week before Wimbledon, Borg examined the contenders for his number one position in 1980: “Jimmy Connors has been my most intense rival for six years,” he wrote. “But at the moment, John McEnroe has the game to give both Jimmy and me sleepless nights. His style is flexible while Jimmy’s is rigid . . . but the fury of a McEnroe/Borg rivalry has not yet had a chance to boil over. It’s still simmering.”

At the same time, McEnroe conceded that “sure, we act differently on court. Once in New Orleans when I went berserk over a call he gently waved his palms up and down to calm me. When we play, the match is always going to be interesting, because of our contrasting styles, with me trying to rush the net and him staying in the backcourt. Sometimes when he and Connors play it’s dull because they both stay in backcourt until someone misses. The most satisfying place for me to beat Bjorn? The French Championships in Paris on clay over five sets.”

Like Muhammad Ali and George Foreman, or Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer, both McEnroe and Borg seemed immediately to see in the other qualities and philosophies that they lacked in themselves, both as players and people. Perhaps unlike those other rivals, though, they each seemed to love the other for his difference. For Borg, McEnroe possessed spontaneity and instinct and was a source of constant surprise. “It sounds strange,” he noted, “but he has more touch than Nastase. He is a master of the unexpected. I can never anticipate his shots.”

For McEnroe, Borg had patience and calm and something like grace. Most of all, he loved the “cleanness” of Borg as an opponent, compared to his own psychological mess. “Borg accepted me,” McEnroe suggests, as if that is all he ever wanted. “There was a level of respect there that I never really reached with anyone else. It was as if he were saying to me, look, we are hitting a tennis ball over the net and this is a pretty damn good way to make a living. And here I was going crazy and thinking he was about to call me an ass. It was beautiful in that way.”

Anyone who has played tennis at any level knows that on court is one of the few places where, generally speaking, you are allowed to talk to yourself, even if it is only to say “C’mmmmmmmooonnnnn!!!” (like Lleyton Hewitt), or “C’mon!” (like Tim Henman). At the time that McEnroe’s game was forming, sports psychology was becoming big business. Few players took a therapist on the road with them, as many do now, but analysis was in the culture, and it was only a matter of time before it became applied to tennis, which, in its balance between extreme action and contemplative inaction, and its relentless examination of the individual, is perhaps the most mentally fraught of

sports.

Many coaches sought to employ the techniques of therapy to their players’ advantage, but few were as successful as W. Timothy Gallwey, who, at the age of fifteen, had missed a heartbreakingly easy volley for match point in the National Junior Tennis Championships in America and always wondered why. In 1976, the year of Borg’s first Wimbledon triumph, Gallwey published a little book called The Inner Game of Tennis, which was pitched, in the spirit of the time, as being somewhere between Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance and How to Win Friends and Influence People. In it he observed that when most people played the game they routinely divided themselves in their heads and, typically, one half of their self railed at the other half, the half that was serving double faults and fluffing volleys.

“Imagine that instead of being two parts of the same person,” Gallwey wrote, “Self 1 and Self 2 are two separate persons. How would you characterise their relationship after witnessing the following conversation between them? The player on court is trying to make a stroke improvement. ‘Okay, dammit, keep your stupid wrist firm,’ he orders. Then as ball after ball comes over the net, Self 1 reminds Self 2, ‘Keep it firm. Keep it firm. Keep it firm!’ Monotonous? Think how Self 2 must feel! It seems as though Self 1 doesn’t think Self 2 hears well, or has a short memory, or is stupid. The truth is, of course, that Self 2, which includes the unconscious mind and nervous system, hears everything, never forgets anything, and is anything but stupid.”

To achieve any kind of success, in tennis, or in life, Gallwey went on to suggest, Self 1, the conscious, nagging, neurotic mind, had to be prepared to get off court. If tennis were taken as a paradigm for life in general, and in particular that kind of modern life which threw pace and spin at you in equal measure, then “the most indispensable tool is the ability to remain calm in the midst of rapid and unsettling changes. The person who will best survive in the present age is the one Kipling described as he who can keep his head while all about are losing theirs. . . .”

In writing this, Gallwey might have been describing Borg, who was almost unique among tennis players in managing, or at least appearing to manage, to take the emotional, self-doubting side of his mind entirely out of his game. In 1980 Borg was insisting, also along with Kipling (whose poem “If” greeted players in the Wimbledon locker room) that “once a match is over, it’s over. I don’t carry either the pain or the glory with me.”

Gallwey would not, however, have known where to begin with McEnroe. The psychologist argued, employing a new phrase, that “ ‘freaking out’ is a general term used for an upset mind. For example, it describes what happens in the mind of many tennis players just after they have hit a shallow lob, or while preparing to serve on match point with the memory of past faults rushing through their minds. Freaking out is [also] what stockbrokers do when the market begins to plunge; or what some parents do when their child has not returned from a date on time. . . . When action is born in worry and self-doubt, it is usually inappropriate and often too late to be effective.”

If Borg sought to remove the fretting of his conscious mind from play, to let habit and faith in his physical strength and skill take over, McEnroe seemed unable and often unwilling to quiet the voices in his head for even a moment. Every shot he played, even his soft-handed instinctive volleying, appeared, to some degree, to have been born out of a titanic internal struggle with “worry and self-doubt.” His face and body language constantly betrayed the fact that he wanted to question the integrity of every ball he went for, every move he took, and every decision he or anyone else made on court.

From the Hardcover edition.