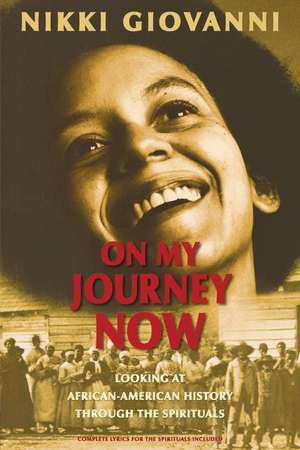

On My Journey Now: Looking at African-American History Through the Spirituals

Autor Nikki Giovannien Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2009 – vârsta de la 12 ani

Ever since she was a little girl attending three different churches, poet Nikki Giovanni has loved the spirituals. Now, with the passion of a poet and the knowledge of a historian, she paints compelling portraits of the lives of her ancestors through the words of songs such as "Go Down, Moses" and "Ain’t Got Time to Die," celebrating a people who overcame enslavement and found a way to survive, to worship, and to build.

Preț: 54.38 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 82

Preț estimativ în valută:

10.41€ • 11.34$ • 8.77£

10.41€ • 11.34$ • 8.77£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780763643805

ISBN-10: 0763643807

Pagini: 128

Ilustrații: 1-COLOR

Dimensiuni: 149 x 233 x 9 mm

Greutate: 0.15 kg

Editura: Candlewick Press (MA)

ISBN-10: 0763643807

Pagini: 128

Ilustrații: 1-COLOR

Dimensiuni: 149 x 233 x 9 mm

Greutate: 0.15 kg

Editura: Candlewick Press (MA)

Notă biografică

Nikki Giovanni is the author of several books for children, most recently ROSA, illustrated by Bryan Collier. Three of her poetry collections for adults have received NAACP Image Awards. She is a University Distinguished Professor at Virginia Tech and lives in Christiansburg, Virginia.

Extras

America was looking for very, very, very cheap labor, because they wanted workers who were even cheaper than indentured servants. The Africans were taken from their homes, their villages, their cities. They were chained and lined up, and people who could not keep up were thrown to the side. So many people dying changed the patterns of the predators, especially the hyenas, the buzzards, the scavengers. The animals came in closer to the coast, following their prey.

They rowed these people out to the sailboats that were going to take them to America. When they put people on ships - and it was deliberate - they separated family groups so they could not speak to each other, so they could not plot. So the slavers had these people on their hands who they had to keep healthy-looking, or else they weren't going to get anything for them. Sometimes they had to force them to eat, because some of them would go on hunger strikes. They were packed head to toe in the ship. Anything that came out of the next person fell on you. So the sailors had to bring you up and pour water on you to more or less wash you. It's not a wash, but it does what it is supposed to do; it gets off all the dirt and mess that is covering you.

We know from the diaries of slave captains that if they brought the Africans up the first or second day, they would jump overboard because the people could just look back and see home. And, having seen it, having recognized that this was not really going to be a good idea at all, and having struggled, they would want to go back. There is something I'm always laughing about: the myth that Africans don't swim, which is crazy. When swimming pools were segregated, that made it harder for African Americans to learn to swim. But of course Africans could swim; many lived near the Atlantic Ocean, and they would swim. In some cases when they jumped overboard, they were shot in the back and wounded and they died, and in other cases they made it. Most ended up in the belly of a shark. The sharks, too, changed their patterns. They began to follow the ships west, feeding on the bodies of the dead or dying Africans.

So the slavers waited, got to that fourth and fifth day, and then there was a calm among the Africans, and they talked about that. There was a calm because they could look out, and although they couldn't see the land, they could see the heat coming off the land. They could see that shimmer, and it's the most fantastic thing to travel to Africa by boat, because you see the heat before you see the land.

And so, by that sixth or seventh day, or maybe around the eighth day, they could no longer see the land or the heat, and so there is going to be a restlessness, because people are beginning to feel lost, because now they're thinking, "Well, this is farther out." So now we have the Africans in a position of not really being able to see anything familiar. But of course they followed the clouds, and we do know that clouds above land are different from clouds over water, so they could see that land had to be that way. And so we're going to have a serious problem somewhere around the tenth day. And those who study this - I'm just a poet, but the people who study slavery - say that those ships' captains knew that this was going to be the day that, I don't want to say all hell is going to break loose, but the day they really have to tighten up, because now the people realize they will not know how to get home.

Fare you well, fare you well, fare you well, everybody.

Fare you well, fare you well, whenever I do get a-home.

What those captured people had - which is why I so admire those people - was a tone, a voice, a moan. They made a decision, because they had to decide: Do we shut ourselves down, or do we continue forward? Now, they ultimately are going to sing a lot of songs; they're going to sing a song that says,

Done made my vow to the Lord,

And I never will turn back.

I will go,

I shall go,

To see what the end will be.

Done opened my mouth to the Lord,

And I never will turn back.

I will go,

I shall go,

To see what the end will be.

So, it's a fabulous thing. But there is also a much sadder song that says,

I told Jesus it would be all right if He changed my name,

I told Jesus it would be all right if He changed my name,

I told Jesus it would be all right if He changed my name.

And He told me that I would go hungry if He changed my name,

And He told me that I would go hungry if He changed my name,

And He told me that I would go hungry if He changed my name.

The Africans are trying to decide, do we continue forward to see what the end will be, or not? Do we agree to change our names, or not? And frankly speaking, I always think it was a woman who started the singing, because I think women do that. Somewhere in the belly of that ship, a woman started in humming, because she couldn't call out and speak to others - there were too many different languages. But she could hum, and that hum, that moan was picked up and went all over the ship and became a single voice. We've heard it in groups like the Moses Hogan Chorale; you hear the voices of all of those people becoming one voice, and it's a moan. But that moan says, "We will find a way; we will continue."

________

ON MY JOURNEY NOW by Nikki Giovanni. Copyright (c) 2007 by Nikki Giovanni. Published by Candlewick Press, Inc., Cambridge, MA.

They rowed these people out to the sailboats that were going to take them to America. When they put people on ships - and it was deliberate - they separated family groups so they could not speak to each other, so they could not plot. So the slavers had these people on their hands who they had to keep healthy-looking, or else they weren't going to get anything for them. Sometimes they had to force them to eat, because some of them would go on hunger strikes. They were packed head to toe in the ship. Anything that came out of the next person fell on you. So the sailors had to bring you up and pour water on you to more or less wash you. It's not a wash, but it does what it is supposed to do; it gets off all the dirt and mess that is covering you.

We know from the diaries of slave captains that if they brought the Africans up the first or second day, they would jump overboard because the people could just look back and see home. And, having seen it, having recognized that this was not really going to be a good idea at all, and having struggled, they would want to go back. There is something I'm always laughing about: the myth that Africans don't swim, which is crazy. When swimming pools were segregated, that made it harder for African Americans to learn to swim. But of course Africans could swim; many lived near the Atlantic Ocean, and they would swim. In some cases when they jumped overboard, they were shot in the back and wounded and they died, and in other cases they made it. Most ended up in the belly of a shark. The sharks, too, changed their patterns. They began to follow the ships west, feeding on the bodies of the dead or dying Africans.

So the slavers waited, got to that fourth and fifth day, and then there was a calm among the Africans, and they talked about that. There was a calm because they could look out, and although they couldn't see the land, they could see the heat coming off the land. They could see that shimmer, and it's the most fantastic thing to travel to Africa by boat, because you see the heat before you see the land.

And so, by that sixth or seventh day, or maybe around the eighth day, they could no longer see the land or the heat, and so there is going to be a restlessness, because people are beginning to feel lost, because now they're thinking, "Well, this is farther out." So now we have the Africans in a position of not really being able to see anything familiar. But of course they followed the clouds, and we do know that clouds above land are different from clouds over water, so they could see that land had to be that way. And so we're going to have a serious problem somewhere around the tenth day. And those who study this - I'm just a poet, but the people who study slavery - say that those ships' captains knew that this was going to be the day that, I don't want to say all hell is going to break loose, but the day they really have to tighten up, because now the people realize they will not know how to get home.

Fare you well, fare you well, fare you well, everybody.

Fare you well, fare you well, whenever I do get a-home.

What those captured people had - which is why I so admire those people - was a tone, a voice, a moan. They made a decision, because they had to decide: Do we shut ourselves down, or do we continue forward? Now, they ultimately are going to sing a lot of songs; they're going to sing a song that says,

Done made my vow to the Lord,

And I never will turn back.

I will go,

I shall go,

To see what the end will be.

Done opened my mouth to the Lord,

And I never will turn back.

I will go,

I shall go,

To see what the end will be.

So, it's a fabulous thing. But there is also a much sadder song that says,

I told Jesus it would be all right if He changed my name,

I told Jesus it would be all right if He changed my name,

I told Jesus it would be all right if He changed my name.

And He told me that I would go hungry if He changed my name,

And He told me that I would go hungry if He changed my name,

And He told me that I would go hungry if He changed my name.

The Africans are trying to decide, do we continue forward to see what the end will be, or not? Do we agree to change our names, or not? And frankly speaking, I always think it was a woman who started the singing, because I think women do that. Somewhere in the belly of that ship, a woman started in humming, because she couldn't call out and speak to others - there were too many different languages. But she could hum, and that hum, that moan was picked up and went all over the ship and became a single voice. We've heard it in groups like the Moses Hogan Chorale; you hear the voices of all of those people becoming one voice, and it's a moan. But that moan says, "We will find a way; we will continue."

________

ON MY JOURNEY NOW by Nikki Giovanni. Copyright (c) 2007 by Nikki Giovanni. Published by Candlewick Press, Inc., Cambridge, MA.

Descriere

With the passion of a poet and the knowledge of a historian, Giovanni tells the story of Africans in America through the glorious words of 46 spirituals, which celebrate a people who overcame enslavement and found a way to survive, to worship, and to build.