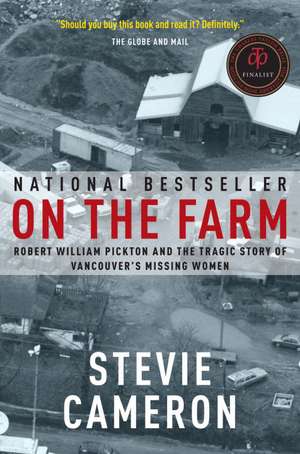

On the Farm: Robert William Pickton and the Tragic Story of Vancouver's Missing Women

Autor Stevie Cameronen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2011

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

RBC Taylor Prize (2011)

Covering the case of one of North America's most prolific serial killer gave Stevie Cameron access not only to the story as it unfolded over many years in two British Columbia courthouses, but also to information unknown to the police - and not in the transcripts of their interviews with Pickton - such as from Pickton's long-time best friend, Lisa Yelds, and from several women who survived terrifying encounters with him. You will now learn what was behind law enforcement's refusal to believe that a serial killer was at work.

Stevie Cameron first began following the story of missing women in 1998, when the odd newspaper piece appeared chronicling the disappearances of drug-addicted sex trade workers from Vancouver's notorious Downtown Eastside. It was February 2002 before Robert William Pickton was arrested, and 2008 before he was found guilty, on six counts of second-degree murder. These counts were appealed and in 2010, the Supreme Court of Canada rendered its conclusion. The guilty verdict was upheld, and finally this unprecedented tale of true crime can be told.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 128.64 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 193

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.62€ • 25.79$ • 20.40£

24.62€ • 25.79$ • 20.40£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 18 martie-01 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780676975857

ISBN-10: 0676975852

Pagini: 768

Ilustrații: 2 8-PAGE PHOTO INSERTS

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 43 mm

Greutate: 0.75 kg

Editura: Vintage Books Canada

ISBN-10: 0676975852

Pagini: 768

Ilustrații: 2 8-PAGE PHOTO INSERTS

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 43 mm

Greutate: 0.75 kg

Editura: Vintage Books Canada

Notă biografică

A woman of many talents, Stevie Cameron is a successful author, investigative journalist, commentator and humanitarian. Her investigative reports have been published by the Globe and Mail and Maclean's, among others, and her award-winning books have brought scandals to the public eye. They include the #1 national bestseller On the Take: Crime, Corruption and Greed in the Mulroney Years and The Last Amigo: Karlheinz Schreiber and the Anatomy of a Scandal, winner of the Crime Writers of Canada Arthur Ellis Award. Cameron's passions for writing, uncovering and dissecting stories of the day have earned her acclaim as one of Canada's foremost investigative journalists. She lives in Toronto.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter One

THE FAMILY FARM

Calling the Pickton place a farm back in 1995 is probably a nice way of putting it. The property, at 963 Dominion Road, across the road from a new shopping centre, was nothing more than a junkyard of old cars, trucks and machinery and enormous mounds of dirt, many of which were covered with black plastic tarps. The Pickton brothers, among their many interests, were in the dirt-moving business. Their shabby white clapboard farmhouse needed painting and repair; the wooden outbuildings—a rickety mess of garages, workshops and sheds—always seemed on the verge of collapse. A shanty that had housed a pigpen had fallen down completely and no one had bothered to tidy up the mess. With no place to keep the pigs, Robert was now stuffing the live weanlings he bought every week at animal auctions into a small horse trailer until he got around to slaughtering them. Only an unpainted hip-roofed Dutch barn looked as if it could last a few more years.

Even though Port Coquitlam was a working-class town of fifty thousand people where few had money to spend fixing up their places, the Pickton farm was infamous, and not just because it was a mess. People knew that the Picktons, who were making a fortune selling off chunks of the land to real estate developers, could easily afford to keep the farm in good repair; it just never occurred to them. That was just how they’d been brought up, not to mind a little mess.

This property wasn’t the family’s original farm. Louise and Leonard Francis Pickton, the parents of David, Robert and Linda, had inherited a family homestead a few kilometres west, on the other side of town in the larger adjoining community of Coquitlam. Louise and Leonard called it L. F. Pickton Ranch Poultry and Pigs. The address, in those days, was 2426 Pitt River Road but it later changed to 2426 Cape Horn.

Today much of this land is crammed with tract housing, but the area in those days was like a vast park blessed with woods, fields and streams, and bears that roamed through the forests around the new hospital. Although the communities here, east of Vancouver, were always mostly working-class, their situation in those days was as favoured as any in the area. The river brimmed with salmon, wild blackberry bushes competed with abundant harvests from the fields and gardens, and the climate was mild. The Coast Mountains to the north and the Cascade Mountains to the south, along the CanadaߝUnited States border, girdled the entire area except the western side, towards Point Grey, at the far end of Vancouver.

The Pickton children—Leonard, Harold, Clifford and Lillian—went to Millside Elementary School, which had been built in 1905, at 1432 Burnett Street in Coquitlam, and the family attended church services at St. Catherine’s Anglican Church in Port Coquitlam.

Lillian married and left the farm, Clifford wound up running a nursing home called the Royal Crescent Convalescent Home and Harold became a night watchman at Flavelle Cedar, a local lumberyard. When Leonard finally inherited the property, he stayed on the farm, although his brothers built houses on lots carved out of the property.

During the 1940s, Leonard, who had been born in England on July 19, 1896, three years before his parents emigrated to Canada, was considered lazy and unambitious by most people who knew him. He seemed to be a confirmed bachelor, content just to work on the farm, but he astonished his relatives by announcing that he was engaged. And not just engaged: he’d snared a woman sixteen years younger than he was, someone he’d met in a coffee shop. It may have been one of his smarter moves; Helen Louise Pickton—born March 20, 1912, in Calgary, Alberta, but raised in a little place called Raymond’s Creek, not far from Swift Current, Saskatchewan—became the driving force in the family.

Linda, their eldest, was born in 1948. Robert, who was called Robbie as a toddler and then almost always Willie, followed on October 24, 1949, and David arrived a year later, in 1950. Willie’s birth was difficult; he was born with the umbilical cord wrapped around his neck and his family wondered afterwards if that had caused some kind of brain damage. But there was nothing wrong with his memory; it has always been remarkable. One of his earliest recollections, he always tells people, is of being only two, living in what had been a chicken coop, and having to lift a floorboard under his bed to get cold water from a spring that ran below. It was the only running water in the house for years.

He also likes to tell people about the time, when he was just three years old, that he crashed his father’s truck, loaded with pigs, into a tree. He was sitting on the driver’s side of his father’s 1940 “Maple Leaf” truck, a Canadian-made General Motors vehicle beloved by farmers in the 1930s and ’40s. Today a Maple Leaf truck is a collector’s item; back then it was a just plain, solid workhorse. Years later, in 1991, Pickton described the incident in detail to a pen pal named Victoria when he sent her an audio letter he called “Bob’s Memoirs.”

“I turn around and the truck started rolling, the pigs all start jumping off and my dad’s running behind the pigs trying to holler to stop the truck,” he says on the tape. “I didn’t know what to do so I smashed it right into a telephone pole. Totalled the truck right out. I sure got the hell beaten out of me. But that’s what happens.”

A year later his mother caught Willie smoking a cigarette and forced him to smoke a cigar to cure him for good. It worked. “That was the last cigarette I ever had,” he said years later.

By anyone’s standards, Louise Pickton was strange. She didn’t just look weird; she behaved outside the norms of convention almost all the time, and as she got older her eccentricity became legendary. To start with, there is no getting past how she looked and how she talked. Like Leonard, she didn’t pay attention to her teeth and eventually most of them rotted out. She lost most of her hair and covered the remaining wisps with a kerchief. Her chin sprouted so many hairs she developed a little goatee that neighbourhood children have never forgotten. “That would blow my mind as a little kid,” remembers one man who occasionally visited the farm as a child. “I would just say to myself, Cut it off!”

And he remembers Louise’s voice, a persistent high screech: “You kids git over here, now!” No one remembers seeing her in shoes, just a pair of men’s thick rubber gumboots. “She waddled like a duck,” another former neighbour says.

Stout and short, with a round face, Louise always wore a cotton housedress over a pair of men’s jeans; when it rained she’d put on an old jacket of Leonard’s. He dressed in much the same kind of costume as his wife: a grubby T-shirt hanging over dirty heavy blue jeans rolled over black rubber boots, and a beat-up old hat. Two of Louise’s children, Linda and Dave, who are also round-faced and short, resemble her, while Willie, tall and narrow-faced with a long, pointed nose, looks like his father. “Rat-faced,” people used to say.

The strongest memories that former neighbours have of Louise today are associated with the family house on Dawes Hill, and later on Dominion Avenue: the smell, the mess, the dirt. Louise didn’t care if the farm animals—chickens, ducks, dogs, even the occasional pig or cow they raised—roamed in and out of the house. She didn’t seem to notice the piles of manure they left behind; she was oblivious to the smell. It was basically a pig farm, after all, and anyone who has lived downwind of one knows what that smell of fresh pig manure is like: piercing and foul, clogging the back of your throat, sticking like scum to your hair and skin. Because the kids had to slop up to two hundred pigs and clean out their pens before and after school, they stank too. They also cleaned up after eight cows that the family milked by hand. In his taped letter to Victoria, Willie said his father delivered the milk to their neighbours.

“The old man also used to pick up garbage from Essondale for his pigs; he’d go up there with his truck to get a freebie,” remembers a man who used to deliver a newspaper to the Picktons. “It seems to me they always had some old trucks around; they were scroungers. They were survivors, resourceful—they had their own ways of doing stuff.

“The farm . . . I can see it: ramshackle, a lot of buildings, went on for about half a block. There was a muddy path down the middle. It was just one shack after another, made up of scraps of lumber. I didn’t go down there. It was so repulsive.”

Once a week or so the kids might have a bath, but it was impossible to get rid of the smell. Neighbouring farmers called Leonard “Piggy” and he never seemed to mind. But the local kids called the boys the same thing, and it hurt. Their own memories of those years are not cozy and warm.

“Things are so modernized these days it’s unbelievable—I had a hard life, I’m telling you, I had a hard life,” Willie told his pen pal years later. He always told people about the homemade or hand-me-down clothes they wore, except for the time Louise bought him a crisp new outfit for Christmas. He was only about five years old, he said, but it was heavily starched and he hated it. “It hurts me, it hurts me,” he complained to his mother, and then he remembers tearing it off and running away in his bare skin.

“These are the stupid things we kind of do,” he told Victoria. “You’re never used to new clothes . . . I was being brought up very, very poorly.”

Even while she was oblivious to the squalor of their lives, Louise wanted her kids to go to Sunday school and birthday parties and ride the school bus like the other children.

“Linda and I went to elementary school together from grade one on and she used to come to the same birthday parties I went to,” remembers one of her classmates. “She wore simple clothes [ordinarily] but her mother would get her party dresses.”

As far as Sunday school went, the only child Louise could bully into going was Linda. Most of the local kids hated it. An elderly retired couple ran it from their small house, right next to the Pickton pig farm. “The Sunday school teacher would come to the foot of the driveway in her big old black Dodge, beep her horn and pick up all the kids,” the classmate said.

Louise had some understanding that it was important for Linda to be like other kids, to have nice clothes, to be included. The same rules didn’t apply to the boys. They didn’t go to Sunday school; they rarely played with other kids. They hung out together, and when they weren’t slopping pigs, they ran wild in the woods around the farm. Like their father, the children went to Millside Elementary on Burnett, where the salmon would come up from the Fraser Creek and spawn. The creeks ran through the farms, including the Picktons’ place, so the boys fished, sometimes with a few neighbourhood children. The most exciting thing that could happen was the arrival of black bears that would amble around the hill looking for pigs to catch at the Pickton farm.

“When one showed up,” remembers a former neighbour, “the Picktons would call the game warden, who’d track it down with dogs all over the farm. The kids would follow. Then they [the warden] would shoot the bear. And all this time the pigs were running free. There was no vegetation where the pigs were because they’d eaten everything and dug big mudholes under the roots of tree stumps. It was a zoo. We’d go there to try to make the pigs chase us.”

As parents, it’s clear that Louise and Leonard were appalling failures. Still, Louise tried in her own twisted way to do her best. She looked out for Willie in particular, knowing that he had a harder time than the others; he was shy and school was almost always an ordeal for him.

“Robert, he just adored Mom,” his sister Linda told Vancouver Sun reporter Kim Bolan in 2002. “He and Mom were so close. Robert was never close to Dad. Robert was kind of Mom’s boy.”

Willie, who started grade one at Millside School in 1955, when he was one month away from his sixth birthday, remembered it later as a one-room school with four grades. “It was quite nice because we had four different blackboards,” he told his pen pal. But a month after he started at Millside he was moved to Viscount Alexander, which was also in Coquitlam. His standard education test results were, according to school records, “very low.”

Grade two was harder for him. His results were a bit better but still “low,” and his teacher decided he needed to be held back and repeat the year. Like all the other kids, Willie had to take standard education tests; by the end of his second try at grade two he was performing at an “average” level. The tests in those years were a mix of standard elementary achievement tests not designed to take into account rural children who might not have access to the advantages of urban kids. In more recent years, with his rural background factored in, Pickton’s test results might have shown him to be doing at least as well as his classmates. His parents certainly never read to him; they would not have encouraged his reading skills, and word recognition was an important factor in scoring higher on these tests.

By the time he was ready for grade three, in the fall of 1958, the school made a decision to place Willie in a class for slow students. He remained in “special education” for the rest of his years in school, even after transferring to a different public school, Mary Hill Elementary in Port Coquitlam. More tests showed that he was performing at the level of a grade-five student, but again the tests were, as teachers sometimes called them, “urbanized,” or set for more sophisticated city kids.

The special ed classes, as they were known, usually had fewer students and more help from teachers. And his tests did show slight improvement year over year in both reading and arithmetic, from outright failure to bare passes in most courses. Robert’s teachers at Mary Hill Elementary nudged him in the direction of occupational classes in high school—blue-collar jobs that wouldn’t require a high level of education or training. So that’s the stream he chose when he turned thirteen and moved on to grade eight at Mary Hill Secondary School in September 1963.

During these years Willie’s attendance was as regular as any other student’s; clearly his parents weren’t putting up with any nonsense about skipping school. He must have wanted to, desperately. Free time on the farm—what there was of it after the chores were done—was basically unsupervised. School, on the other hand, was a nightmare, not just for Willie but for his brother and sister as well. Part of the reason was that they were shunned by the children, most of them doctors’ kids, who lived closest to them.

For several years the Picktons’ nearest neighbour was the new Essondale Hospital, built on a thousand acres of cleared land at the top of their hill to house mental patients. Essondale, named after Dr. Henry Esson Young, the provincial politician responsible for it, had been designed to replace B.C.’s first hospital for the mentally ill, the Provincial Hospital for the Insane, which was built in 1878 in New Westminster; five years later the government introduced work therapy, putting the patients to work in the gardens. But soon there were so many patients—more than three hundred by 1899—that planning began to build a “Hospital for the Mind” in Coquitlam, to care for psychiatric patients as well as physically and mentally handicapped children and adults. Construction started in 1905.

By the time the Pickton kids were climbing onto a school bus in the 1950s, Essondale had become a sprawling hospital complex. Five handsome houses on the hill were for the senior doctors who worked there; others, known as “the mechanical homes,” were for the top engineers and administrators who kept the place running. These were big houses, all with views over the hospital grounds and the river; all with large living and dining rooms, floors laid of mahogany, plenty of bedrooms; all well landscaped on large lots. Most of the kids on the school bus came from these houses; they walked down the hill in nice clothes, through gardens and apple orchards, to wait for the bus at the same roadside corner as the Pickton kids.

Along with the Picktons there were a few other students from the bottom of the hill, poorer, from farm homes. These kids would enter the bus with peashooters and pick fights. The problem for the Pickton kids is that they didn’t fit into this gang either.

“We were all terrible to the Picktons, especially to Robert,” says a doctor’s daughter who now lives in Alberta. Part of the reason was that the boys had speech problems. Dave talked too fast and high; he couldn’t pronounce his R’s, so he sounded like Elmer Fudd, especially when he was worked up about something. Willie was withdrawn and didn’t talk much at all; when he did, he too would gabble in a high, fast voice. People remarked later on their strange voices, but to those who knew them in the old days they seemed perfectly normal—Leonard and his brothers had the same squeaky high voices.

“I remember all of us on the road taunting him,” says the doctor’s daughter. “We’d say to each other, ‘Just let us at him now and we’ll make him talk.’ How were they different? Dirty and stinky. They always had their hair cut in a brush cut. Man, they stunk. Their house was a poor house with no yard and falling-down fences. There were no big trees, only some shrubs. I don’t even remember them at school at all but I do remember them waiting for the school bus. Our bunch was mostly all doctors’ kids. We were the best-dressed and had the nicest houses; almost everyone in the group is successful now.”

What she and her pals share with the poor kids such as the Picktons—the kids they despised—is the memory that the area was a perfect place to grow up: “Essondale had orchards and they were ours for the picking. There was a lost lake called Mundy Lake, surrounded by trees and bushes, out in the middle of the forest. It was idyllic. We could do what we liked as long as we were home for supper. But the Pickton kids never played with us.”

Paradise or not, it sounds more like Lord of the Flies than Tom Sawyer or Huckleberry Finn. Or perhaps even more like One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest. That’s because, along with Essondale, which served the entire province of British Columbia, the provincial government built even more institutions all around the farmland.

When the government first moved three hundred male patients from the overcrowded Provincial Hospital for the Insane, known as PHI, in New Westminster to the Coquitlam site near the Picktons, it changed the name of the New Westminster hospital to Woodlands and turned it into a residence mainly for mentally and physically disabled kids, including babies. As they grew up, Woodlands patients would be transferred to the rambling new thousand-acre hillside site now called Essondale. Several years later, the women from the New Westminster hospital were also moved to Essondale.

On the southwest side of the property, the building originally called the Male Building and then West Lawn held the men; the building on the east side was East Lawn, with room for 675 women. In the centre was the Acute Psychopathic Unit, where new patients were tested; it was later known as Centre Lawn. In those early years there were no corrections officers to handle the criminally insane, just nurses and a few supervisors and doctors. Patients slept in rows in large rooms; by day up to a hundred women, for example, could be in one large room in East Lawn, cared for by a handful of student nurses and two supervisors.

More units were added to the property. A veterans’ building opened in 1934; two years later an old school for boys was renovated to become Valleyview Hospital Unit, an old-age home. Other buildings followed until the place was filled with one kind of patient after another. What they all had in common was that these were special-needs patients, and many of them were insane.

By 1951 Essondale, with 4,630 patients, was like a small town, with many of its inhabitants working on the various properties. Patients mowed the doctors’ lawns and kept the gardens blooming and groomed. At the same time, many of them were allowed to wander all over the place; one day a sister and brother from one of the doctors’ houses were playing in the water and found a dead patient floating there.

Patients who needed psychiatric assessment before being transferred to the appropriate centre at Essondale also worked in the dairy, fields and barns of Colony Farm. This was a working farm at the bottom of the hill below the Pickton property that provided food for all the patients and staff at Essondale and Woodlands. Government records show that farm supervisors used patient labour to clear and dike the original land there to prepare it for farming use. Doctors would take their children down to Colony Farm to see the prized Colony Clydesdales, which won awards at the Pacific National Exhibition every year. Government statistical records brag that it was regarded as “the best farm in Western Canada” and produced “over 700 tons of crops and 200,000 gallons of milk a year.” The patient-labourers were the ones who made this possible. And some of those Colony Farm patients, like some from Essondale, often worked for the Picktons on their farm up on Dawes Hill.

There is a story you hear when local people get talking about the Picktons during the Dawes Hill years, that when he was little, Willie used to crawl into the carcasses of gutted hogs to hide from people who were angry with him. If this is true, the Picktons have never said so.

Willie himself has told another story, over and over again, to anyone who would listen, of an incident that devastated him when he was about twelve years old. He’d gone to a livestock auction with his parents and had enough money saved—thirty-five dollars—to buy a three-week-old black and white calf: “As really pretty as the day is long” is how he described it later to his pen pal Victoria. “It was a nice calf and I was going to keep the calf for the rest of my life.” Every day after school he looked forward to coming home to feed it. Then one day when he returned, he couldn’t find his calf; frantically he searched all around the property.

“I went everywheres looking for this here calf and I couldn’t find it anywheres,” he said years later. “They says, ‘Oh, it must have got out.’ I said, ‘How can it get out the door? The door is locked.’”

Exasperated by his nagging, someone, probably his father, finally turned to him and suggested he look in the barn. Willie raced off and burst through the doors of the barn. “And here I seen the calf hanging upside down there, they butchered my calf on me. Oh boy, I was mad. I couldn’t talk to anybody for three or four days. I locked everybody out of my own mind, I didn’t want to talk to anybody.”

Louise tried to appease him by giving him an extra twenty dollars for it. But he remained upset. “Like my mother says,” he told a friend later, “‘That was a good dollar for the calf. . . . You can go buy another.’ And I says, ‘No, I was going to keep that calf for the rest of my life and now it’s gone.’ That really upset me, but that happens. That’s life. I mean we’re only here for so long . . . When your time is over, your time is over.”

And there is another story about him at that age, although he’s not the one who tells it. A little girl who became his friend many years later remembers Willie today as “a sweet boy.” At the time his parents were selling their meat from the small store the locals called “the meat locker,” which they had opened on the north side of the Lougheed Highway at Shaughnessy Street in Port Coquitlam. Lisa Yelds, whose father was white and mother Chinese, and who was only five years old back in 1962, was being cared for by her grandparents after being abandoned by her parents. Her Chinese grandfather liked to take her fishing on the Stave River near Mission Slough, and on the way home to Coquitlam he’d often stop at the Picktons’ store for meat. Lisa Yelds remembers seeing a young boy there, a boy the others called Willie.

“Willie was helping in the store, and I guess he was about nine or ten. What really struck me was his blond hair. He was working beside a stout and stocky older lady, his mother. One day he looked at me and smiled and then he gave me a bag of hot dogs. Like a present. I wasn’t used to people being nice to me. I never forgot him.”

It would be nearly another thirty years before Lisa Yelds and Willie Pickton met again, this time as neighbours on Dominion Avenue, where he would become her best friend. And she would become his.

From the Hardcover edition.

THE FAMILY FARM

Calling the Pickton place a farm back in 1995 is probably a nice way of putting it. The property, at 963 Dominion Road, across the road from a new shopping centre, was nothing more than a junkyard of old cars, trucks and machinery and enormous mounds of dirt, many of which were covered with black plastic tarps. The Pickton brothers, among their many interests, were in the dirt-moving business. Their shabby white clapboard farmhouse needed painting and repair; the wooden outbuildings—a rickety mess of garages, workshops and sheds—always seemed on the verge of collapse. A shanty that had housed a pigpen had fallen down completely and no one had bothered to tidy up the mess. With no place to keep the pigs, Robert was now stuffing the live weanlings he bought every week at animal auctions into a small horse trailer until he got around to slaughtering them. Only an unpainted hip-roofed Dutch barn looked as if it could last a few more years.

Even though Port Coquitlam was a working-class town of fifty thousand people where few had money to spend fixing up their places, the Pickton farm was infamous, and not just because it was a mess. People knew that the Picktons, who were making a fortune selling off chunks of the land to real estate developers, could easily afford to keep the farm in good repair; it just never occurred to them. That was just how they’d been brought up, not to mind a little mess.

This property wasn’t the family’s original farm. Louise and Leonard Francis Pickton, the parents of David, Robert and Linda, had inherited a family homestead a few kilometres west, on the other side of town in the larger adjoining community of Coquitlam. Louise and Leonard called it L. F. Pickton Ranch Poultry and Pigs. The address, in those days, was 2426 Pitt River Road but it later changed to 2426 Cape Horn.

Today much of this land is crammed with tract housing, but the area in those days was like a vast park blessed with woods, fields and streams, and bears that roamed through the forests around the new hospital. Although the communities here, east of Vancouver, were always mostly working-class, their situation in those days was as favoured as any in the area. The river brimmed with salmon, wild blackberry bushes competed with abundant harvests from the fields and gardens, and the climate was mild. The Coast Mountains to the north and the Cascade Mountains to the south, along the CanadaߝUnited States border, girdled the entire area except the western side, towards Point Grey, at the far end of Vancouver.

The Pickton children—Leonard, Harold, Clifford and Lillian—went to Millside Elementary School, which had been built in 1905, at 1432 Burnett Street in Coquitlam, and the family attended church services at St. Catherine’s Anglican Church in Port Coquitlam.

Lillian married and left the farm, Clifford wound up running a nursing home called the Royal Crescent Convalescent Home and Harold became a night watchman at Flavelle Cedar, a local lumberyard. When Leonard finally inherited the property, he stayed on the farm, although his brothers built houses on lots carved out of the property.

During the 1940s, Leonard, who had been born in England on July 19, 1896, three years before his parents emigrated to Canada, was considered lazy and unambitious by most people who knew him. He seemed to be a confirmed bachelor, content just to work on the farm, but he astonished his relatives by announcing that he was engaged. And not just engaged: he’d snared a woman sixteen years younger than he was, someone he’d met in a coffee shop. It may have been one of his smarter moves; Helen Louise Pickton—born March 20, 1912, in Calgary, Alberta, but raised in a little place called Raymond’s Creek, not far from Swift Current, Saskatchewan—became the driving force in the family.

Linda, their eldest, was born in 1948. Robert, who was called Robbie as a toddler and then almost always Willie, followed on October 24, 1949, and David arrived a year later, in 1950. Willie’s birth was difficult; he was born with the umbilical cord wrapped around his neck and his family wondered afterwards if that had caused some kind of brain damage. But there was nothing wrong with his memory; it has always been remarkable. One of his earliest recollections, he always tells people, is of being only two, living in what had been a chicken coop, and having to lift a floorboard under his bed to get cold water from a spring that ran below. It was the only running water in the house for years.

He also likes to tell people about the time, when he was just three years old, that he crashed his father’s truck, loaded with pigs, into a tree. He was sitting on the driver’s side of his father’s 1940 “Maple Leaf” truck, a Canadian-made General Motors vehicle beloved by farmers in the 1930s and ’40s. Today a Maple Leaf truck is a collector’s item; back then it was a just plain, solid workhorse. Years later, in 1991, Pickton described the incident in detail to a pen pal named Victoria when he sent her an audio letter he called “Bob’s Memoirs.”

“I turn around and the truck started rolling, the pigs all start jumping off and my dad’s running behind the pigs trying to holler to stop the truck,” he says on the tape. “I didn’t know what to do so I smashed it right into a telephone pole. Totalled the truck right out. I sure got the hell beaten out of me. But that’s what happens.”

A year later his mother caught Willie smoking a cigarette and forced him to smoke a cigar to cure him for good. It worked. “That was the last cigarette I ever had,” he said years later.

By anyone’s standards, Louise Pickton was strange. She didn’t just look weird; she behaved outside the norms of convention almost all the time, and as she got older her eccentricity became legendary. To start with, there is no getting past how she looked and how she talked. Like Leonard, she didn’t pay attention to her teeth and eventually most of them rotted out. She lost most of her hair and covered the remaining wisps with a kerchief. Her chin sprouted so many hairs she developed a little goatee that neighbourhood children have never forgotten. “That would blow my mind as a little kid,” remembers one man who occasionally visited the farm as a child. “I would just say to myself, Cut it off!”

And he remembers Louise’s voice, a persistent high screech: “You kids git over here, now!” No one remembers seeing her in shoes, just a pair of men’s thick rubber gumboots. “She waddled like a duck,” another former neighbour says.

Stout and short, with a round face, Louise always wore a cotton housedress over a pair of men’s jeans; when it rained she’d put on an old jacket of Leonard’s. He dressed in much the same kind of costume as his wife: a grubby T-shirt hanging over dirty heavy blue jeans rolled over black rubber boots, and a beat-up old hat. Two of Louise’s children, Linda and Dave, who are also round-faced and short, resemble her, while Willie, tall and narrow-faced with a long, pointed nose, looks like his father. “Rat-faced,” people used to say.

The strongest memories that former neighbours have of Louise today are associated with the family house on Dawes Hill, and later on Dominion Avenue: the smell, the mess, the dirt. Louise didn’t care if the farm animals—chickens, ducks, dogs, even the occasional pig or cow they raised—roamed in and out of the house. She didn’t seem to notice the piles of manure they left behind; she was oblivious to the smell. It was basically a pig farm, after all, and anyone who has lived downwind of one knows what that smell of fresh pig manure is like: piercing and foul, clogging the back of your throat, sticking like scum to your hair and skin. Because the kids had to slop up to two hundred pigs and clean out their pens before and after school, they stank too. They also cleaned up after eight cows that the family milked by hand. In his taped letter to Victoria, Willie said his father delivered the milk to their neighbours.

“The old man also used to pick up garbage from Essondale for his pigs; he’d go up there with his truck to get a freebie,” remembers a man who used to deliver a newspaper to the Picktons. “It seems to me they always had some old trucks around; they were scroungers. They were survivors, resourceful—they had their own ways of doing stuff.

“The farm . . . I can see it: ramshackle, a lot of buildings, went on for about half a block. There was a muddy path down the middle. It was just one shack after another, made up of scraps of lumber. I didn’t go down there. It was so repulsive.”

Once a week or so the kids might have a bath, but it was impossible to get rid of the smell. Neighbouring farmers called Leonard “Piggy” and he never seemed to mind. But the local kids called the boys the same thing, and it hurt. Their own memories of those years are not cozy and warm.

“Things are so modernized these days it’s unbelievable—I had a hard life, I’m telling you, I had a hard life,” Willie told his pen pal years later. He always told people about the homemade or hand-me-down clothes they wore, except for the time Louise bought him a crisp new outfit for Christmas. He was only about five years old, he said, but it was heavily starched and he hated it. “It hurts me, it hurts me,” he complained to his mother, and then he remembers tearing it off and running away in his bare skin.

“These are the stupid things we kind of do,” he told Victoria. “You’re never used to new clothes . . . I was being brought up very, very poorly.”

Even while she was oblivious to the squalor of their lives, Louise wanted her kids to go to Sunday school and birthday parties and ride the school bus like the other children.

“Linda and I went to elementary school together from grade one on and she used to come to the same birthday parties I went to,” remembers one of her classmates. “She wore simple clothes [ordinarily] but her mother would get her party dresses.”

As far as Sunday school went, the only child Louise could bully into going was Linda. Most of the local kids hated it. An elderly retired couple ran it from their small house, right next to the Pickton pig farm. “The Sunday school teacher would come to the foot of the driveway in her big old black Dodge, beep her horn and pick up all the kids,” the classmate said.

Louise had some understanding that it was important for Linda to be like other kids, to have nice clothes, to be included. The same rules didn’t apply to the boys. They didn’t go to Sunday school; they rarely played with other kids. They hung out together, and when they weren’t slopping pigs, they ran wild in the woods around the farm. Like their father, the children went to Millside Elementary on Burnett, where the salmon would come up from the Fraser Creek and spawn. The creeks ran through the farms, including the Picktons’ place, so the boys fished, sometimes with a few neighbourhood children. The most exciting thing that could happen was the arrival of black bears that would amble around the hill looking for pigs to catch at the Pickton farm.

“When one showed up,” remembers a former neighbour, “the Picktons would call the game warden, who’d track it down with dogs all over the farm. The kids would follow. Then they [the warden] would shoot the bear. And all this time the pigs were running free. There was no vegetation where the pigs were because they’d eaten everything and dug big mudholes under the roots of tree stumps. It was a zoo. We’d go there to try to make the pigs chase us.”

As parents, it’s clear that Louise and Leonard were appalling failures. Still, Louise tried in her own twisted way to do her best. She looked out for Willie in particular, knowing that he had a harder time than the others; he was shy and school was almost always an ordeal for him.

“Robert, he just adored Mom,” his sister Linda told Vancouver Sun reporter Kim Bolan in 2002. “He and Mom were so close. Robert was never close to Dad. Robert was kind of Mom’s boy.”

Willie, who started grade one at Millside School in 1955, when he was one month away from his sixth birthday, remembered it later as a one-room school with four grades. “It was quite nice because we had four different blackboards,” he told his pen pal. But a month after he started at Millside he was moved to Viscount Alexander, which was also in Coquitlam. His standard education test results were, according to school records, “very low.”

Grade two was harder for him. His results were a bit better but still “low,” and his teacher decided he needed to be held back and repeat the year. Like all the other kids, Willie had to take standard education tests; by the end of his second try at grade two he was performing at an “average” level. The tests in those years were a mix of standard elementary achievement tests not designed to take into account rural children who might not have access to the advantages of urban kids. In more recent years, with his rural background factored in, Pickton’s test results might have shown him to be doing at least as well as his classmates. His parents certainly never read to him; they would not have encouraged his reading skills, and word recognition was an important factor in scoring higher on these tests.

By the time he was ready for grade three, in the fall of 1958, the school made a decision to place Willie in a class for slow students. He remained in “special education” for the rest of his years in school, even after transferring to a different public school, Mary Hill Elementary in Port Coquitlam. More tests showed that he was performing at the level of a grade-five student, but again the tests were, as teachers sometimes called them, “urbanized,” or set for more sophisticated city kids.

The special ed classes, as they were known, usually had fewer students and more help from teachers. And his tests did show slight improvement year over year in both reading and arithmetic, from outright failure to bare passes in most courses. Robert’s teachers at Mary Hill Elementary nudged him in the direction of occupational classes in high school—blue-collar jobs that wouldn’t require a high level of education or training. So that’s the stream he chose when he turned thirteen and moved on to grade eight at Mary Hill Secondary School in September 1963.

During these years Willie’s attendance was as regular as any other student’s; clearly his parents weren’t putting up with any nonsense about skipping school. He must have wanted to, desperately. Free time on the farm—what there was of it after the chores were done—was basically unsupervised. School, on the other hand, was a nightmare, not just for Willie but for his brother and sister as well. Part of the reason was that they were shunned by the children, most of them doctors’ kids, who lived closest to them.

For several years the Picktons’ nearest neighbour was the new Essondale Hospital, built on a thousand acres of cleared land at the top of their hill to house mental patients. Essondale, named after Dr. Henry Esson Young, the provincial politician responsible for it, had been designed to replace B.C.’s first hospital for the mentally ill, the Provincial Hospital for the Insane, which was built in 1878 in New Westminster; five years later the government introduced work therapy, putting the patients to work in the gardens. But soon there were so many patients—more than three hundred by 1899—that planning began to build a “Hospital for the Mind” in Coquitlam, to care for psychiatric patients as well as physically and mentally handicapped children and adults. Construction started in 1905.

By the time the Pickton kids were climbing onto a school bus in the 1950s, Essondale had become a sprawling hospital complex. Five handsome houses on the hill were for the senior doctors who worked there; others, known as “the mechanical homes,” were for the top engineers and administrators who kept the place running. These were big houses, all with views over the hospital grounds and the river; all with large living and dining rooms, floors laid of mahogany, plenty of bedrooms; all well landscaped on large lots. Most of the kids on the school bus came from these houses; they walked down the hill in nice clothes, through gardens and apple orchards, to wait for the bus at the same roadside corner as the Pickton kids.

Along with the Picktons there were a few other students from the bottom of the hill, poorer, from farm homes. These kids would enter the bus with peashooters and pick fights. The problem for the Pickton kids is that they didn’t fit into this gang either.

“We were all terrible to the Picktons, especially to Robert,” says a doctor’s daughter who now lives in Alberta. Part of the reason was that the boys had speech problems. Dave talked too fast and high; he couldn’t pronounce his R’s, so he sounded like Elmer Fudd, especially when he was worked up about something. Willie was withdrawn and didn’t talk much at all; when he did, he too would gabble in a high, fast voice. People remarked later on their strange voices, but to those who knew them in the old days they seemed perfectly normal—Leonard and his brothers had the same squeaky high voices.

“I remember all of us on the road taunting him,” says the doctor’s daughter. “We’d say to each other, ‘Just let us at him now and we’ll make him talk.’ How were they different? Dirty and stinky. They always had their hair cut in a brush cut. Man, they stunk. Their house was a poor house with no yard and falling-down fences. There were no big trees, only some shrubs. I don’t even remember them at school at all but I do remember them waiting for the school bus. Our bunch was mostly all doctors’ kids. We were the best-dressed and had the nicest houses; almost everyone in the group is successful now.”

What she and her pals share with the poor kids such as the Picktons—the kids they despised—is the memory that the area was a perfect place to grow up: “Essondale had orchards and they were ours for the picking. There was a lost lake called Mundy Lake, surrounded by trees and bushes, out in the middle of the forest. It was idyllic. We could do what we liked as long as we were home for supper. But the Pickton kids never played with us.”

Paradise or not, it sounds more like Lord of the Flies than Tom Sawyer or Huckleberry Finn. Or perhaps even more like One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest. That’s because, along with Essondale, which served the entire province of British Columbia, the provincial government built even more institutions all around the farmland.

When the government first moved three hundred male patients from the overcrowded Provincial Hospital for the Insane, known as PHI, in New Westminster to the Coquitlam site near the Picktons, it changed the name of the New Westminster hospital to Woodlands and turned it into a residence mainly for mentally and physically disabled kids, including babies. As they grew up, Woodlands patients would be transferred to the rambling new thousand-acre hillside site now called Essondale. Several years later, the women from the New Westminster hospital were also moved to Essondale.

On the southwest side of the property, the building originally called the Male Building and then West Lawn held the men; the building on the east side was East Lawn, with room for 675 women. In the centre was the Acute Psychopathic Unit, where new patients were tested; it was later known as Centre Lawn. In those early years there were no corrections officers to handle the criminally insane, just nurses and a few supervisors and doctors. Patients slept in rows in large rooms; by day up to a hundred women, for example, could be in one large room in East Lawn, cared for by a handful of student nurses and two supervisors.

More units were added to the property. A veterans’ building opened in 1934; two years later an old school for boys was renovated to become Valleyview Hospital Unit, an old-age home. Other buildings followed until the place was filled with one kind of patient after another. What they all had in common was that these were special-needs patients, and many of them were insane.

By 1951 Essondale, with 4,630 patients, was like a small town, with many of its inhabitants working on the various properties. Patients mowed the doctors’ lawns and kept the gardens blooming and groomed. At the same time, many of them were allowed to wander all over the place; one day a sister and brother from one of the doctors’ houses were playing in the water and found a dead patient floating there.

Patients who needed psychiatric assessment before being transferred to the appropriate centre at Essondale also worked in the dairy, fields and barns of Colony Farm. This was a working farm at the bottom of the hill below the Pickton property that provided food for all the patients and staff at Essondale and Woodlands. Government records show that farm supervisors used patient labour to clear and dike the original land there to prepare it for farming use. Doctors would take their children down to Colony Farm to see the prized Colony Clydesdales, which won awards at the Pacific National Exhibition every year. Government statistical records brag that it was regarded as “the best farm in Western Canada” and produced “over 700 tons of crops and 200,000 gallons of milk a year.” The patient-labourers were the ones who made this possible. And some of those Colony Farm patients, like some from Essondale, often worked for the Picktons on their farm up on Dawes Hill.

There is a story you hear when local people get talking about the Picktons during the Dawes Hill years, that when he was little, Willie used to crawl into the carcasses of gutted hogs to hide from people who were angry with him. If this is true, the Picktons have never said so.

Willie himself has told another story, over and over again, to anyone who would listen, of an incident that devastated him when he was about twelve years old. He’d gone to a livestock auction with his parents and had enough money saved—thirty-five dollars—to buy a three-week-old black and white calf: “As really pretty as the day is long” is how he described it later to his pen pal Victoria. “It was a nice calf and I was going to keep the calf for the rest of my life.” Every day after school he looked forward to coming home to feed it. Then one day when he returned, he couldn’t find his calf; frantically he searched all around the property.

“I went everywheres looking for this here calf and I couldn’t find it anywheres,” he said years later. “They says, ‘Oh, it must have got out.’ I said, ‘How can it get out the door? The door is locked.’”

Exasperated by his nagging, someone, probably his father, finally turned to him and suggested he look in the barn. Willie raced off and burst through the doors of the barn. “And here I seen the calf hanging upside down there, they butchered my calf on me. Oh boy, I was mad. I couldn’t talk to anybody for three or four days. I locked everybody out of my own mind, I didn’t want to talk to anybody.”

Louise tried to appease him by giving him an extra twenty dollars for it. But he remained upset. “Like my mother says,” he told a friend later, “‘That was a good dollar for the calf. . . . You can go buy another.’ And I says, ‘No, I was going to keep that calf for the rest of my life and now it’s gone.’ That really upset me, but that happens. That’s life. I mean we’re only here for so long . . . When your time is over, your time is over.”

And there is another story about him at that age, although he’s not the one who tells it. A little girl who became his friend many years later remembers Willie today as “a sweet boy.” At the time his parents were selling their meat from the small store the locals called “the meat locker,” which they had opened on the north side of the Lougheed Highway at Shaughnessy Street in Port Coquitlam. Lisa Yelds, whose father was white and mother Chinese, and who was only five years old back in 1962, was being cared for by her grandparents after being abandoned by her parents. Her Chinese grandfather liked to take her fishing on the Stave River near Mission Slough, and on the way home to Coquitlam he’d often stop at the Picktons’ store for meat. Lisa Yelds remembers seeing a young boy there, a boy the others called Willie.

“Willie was helping in the store, and I guess he was about nine or ten. What really struck me was his blond hair. He was working beside a stout and stocky older lady, his mother. One day he looked at me and smiled and then he gave me a bag of hot dogs. Like a present. I wasn’t used to people being nice to me. I never forgot him.”

It would be nearly another thirty years before Lisa Yelds and Willie Pickton met again, this time as neighbours on Dominion Avenue, where he would become her best friend. And she would become his.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

NATIONAL BESTSELLER

“Rich with detail. . . . Should you buy this book and read it? Definitely.”

— Neil Boyd, The Globe and Mail

"Stevie Cameron, who brought the art of political investigative journalism in Canada to new heights over the last three decades, has distinguished herself and her profession once again… [On the Farm] will surely remain a classic for generations of crime readers to come."

— Winnipeg Free Press

"On the Farm is the book you were hoping for… A hard-hitting look at the botched police investigations of Pickton."

— The Vancouver Sun

"No writer knows this story better than Cameron… [On the Farm] will go down as the definitive resource on the Pickton affair."

— Maclean's

"Stevie Cameron has written yet another great book exposing, as is her wont, the 'comfortable establishment' in our country of indifference to societal ills that might be expensive nuisances to deal with."

— The Tyee

From the Hardcover edition.

“Rich with detail. . . . Should you buy this book and read it? Definitely.”

— Neil Boyd, The Globe and Mail

"Stevie Cameron, who brought the art of political investigative journalism in Canada to new heights over the last three decades, has distinguished herself and her profession once again… [On the Farm] will surely remain a classic for generations of crime readers to come."

— Winnipeg Free Press

"On the Farm is the book you were hoping for… A hard-hitting look at the botched police investigations of Pickton."

— The Vancouver Sun

"No writer knows this story better than Cameron… [On the Farm] will go down as the definitive resource on the Pickton affair."

— Maclean's

"Stevie Cameron has written yet another great book exposing, as is her wont, the 'comfortable establishment' in our country of indifference to societal ills that might be expensive nuisances to deal with."

— The Tyee

From the Hardcover edition.

Cuprins

Maps

Author’s note

Part One: The Family

Prologue: Jane Doe

1. The Family Farm

2. Dominion Avenue

3. A Mother’s Will

4. The Pickton Brothers

5. Geography Speaks

6. Cops under Fire

7. A Motley Crew

8. Prime Suspect

9. The Trials of Kim Rossmo and the Growing List of Missing Women

10. Lisa Yelds

11. Piggy’s Palace

12. Maggy Gisle, Cara Ellis and Sandra Gail Ringwald

13. Gina and Willie and More Missing Women

14. Sherry Irving and Marnie Frey

15. The Worst Year

16. Sarah de Vries and Sheila Egan

17. A Doomed Investigation

18. Project Amelia: A Bad Start

19. Roommates

Part Two: The Missing Women

20. What They Saw

21. What Did the Police Do?

22. Closing In on Willie

23. Another Close Call

24. Deadly Girlfriends

25. Rossmo Out

26. Panic on Skid Row

27. The File Review

28. Do Something

29. A Newsroom Leads the Way

30. Police on Trial

31. The Last Woman

32. The Rookie Cop

33. Twenty-Four Hours

34. The Largest Crime Scene in Canadian History

35. Scott Chubb

Part Three: On the Farm

36. Getting Ready for Willie

37. Mike Petrie Wants the Job

38. The Cell Plant

39. The Fordy Interview

40. Don Adam Takes Over

41. Back in the Cell

42. Taking Willie to the Judge

43. In the Workshop

44. The Forensic Team

45. Talking to the Families

46. What the Dead Reveal

47. Willie Goes to Court

48. Telling Tales: Andy Bellwood, Sandra Gail Ringwald and Gina Houston

49. The Last Witnesses

50. The Aristocracy of Victimhood

51. From Twenty-Six to Six

52. The Jury

53. Guilty! But of What?

Aftermath

Acknowledgments

Photo Credits

Index

From the Hardcover edition.

Author’s note

Part One: The Family

Prologue: Jane Doe

1. The Family Farm

2. Dominion Avenue

3. A Mother’s Will

4. The Pickton Brothers

5. Geography Speaks

6. Cops under Fire

7. A Motley Crew

8. Prime Suspect

9. The Trials of Kim Rossmo and the Growing List of Missing Women

10. Lisa Yelds

11. Piggy’s Palace

12. Maggy Gisle, Cara Ellis and Sandra Gail Ringwald

13. Gina and Willie and More Missing Women

14. Sherry Irving and Marnie Frey

15. The Worst Year

16. Sarah de Vries and Sheila Egan

17. A Doomed Investigation

18. Project Amelia: A Bad Start

19. Roommates

Part Two: The Missing Women

20. What They Saw

21. What Did the Police Do?

22. Closing In on Willie

23. Another Close Call

24. Deadly Girlfriends

25. Rossmo Out

26. Panic on Skid Row

27. The File Review

28. Do Something

29. A Newsroom Leads the Way

30. Police on Trial

31. The Last Woman

32. The Rookie Cop

33. Twenty-Four Hours

34. The Largest Crime Scene in Canadian History

35. Scott Chubb

Part Three: On the Farm

36. Getting Ready for Willie

37. Mike Petrie Wants the Job

38. The Cell Plant

39. The Fordy Interview

40. Don Adam Takes Over

41. Back in the Cell

42. Taking Willie to the Judge

43. In the Workshop

44. The Forensic Team

45. Talking to the Families

46. What the Dead Reveal

47. Willie Goes to Court

48. Telling Tales: Andy Bellwood, Sandra Gail Ringwald and Gina Houston

49. The Last Witnesses

50. The Aristocracy of Victimhood

51. From Twenty-Six to Six

52. The Jury

53. Guilty! But of What?

Aftermath

Acknowledgments

Photo Credits

Index

From the Hardcover edition.

Premii

- RBC Taylor Prize Finalist, 2011