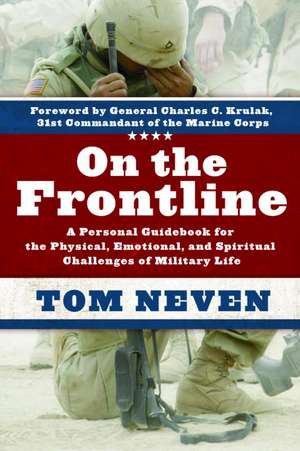

On the Frontline: A Personal Guidebook for the Physical, Emotional, and Spiritual Challenges of Military Life

Autor Tom Neven Charles C. Krulaken Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2006

The demands of military life can be staggering. Soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines face pressures and temptations that civilians will never know. Fortunately, here is help from someone who has been there.

Tom Neven uses examples from history, real-life anecdotes from men and women in uniform, and biblical wisdom to help you navigate the biggest challenges of military life. On the Frontline addresses issues such as:

·Loneliness (how to cope with deployment and separation from family and friends)

·Sex (how to resist temptation and remain faithful)

·Debt (how to manage money and avoid financial traps)

·Relationships (how to build and maintain a marriage, friendships, and other relationships from a distance)

·Fear (how to deal with the threat of injury or death)

Written for both men and women, this powerful book confronts these and other issues head-on, offering hope, encouragement, and practical guidance for every day you serve On the Frontline.

Preț: 92.14 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 138

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.63€ • 18.34$ • 14.56£

17.63€ • 18.34$ • 14.56£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400073351

ISBN-10: 1400073359

Pagini: 215

Dimensiuni: 141 x 187 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Waterbrook Press

ISBN-10: 1400073359

Pagini: 215

Dimensiuni: 141 x 187 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Waterbrook Press

Notă biografică

Tom Neven is an author, editor, and former Marine who served seven years as an M-60 machine gunner and a U.S. embassy guard in Africa and Europe. He covered the first Gulf War for The Marine Corps Gazette, and has written for numerous newspapers and magazines. He is currently senior editor of Plugged In, a Focus on the Family magazine/Web site. He and his wife, Colette, are the parents of two children and live in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Extras

Challenge. The word could be synonymous with “military.” In fact, you probably entered the military welcoming the challenge, seeking to test yourself against the best. You wanted to prove you have what it takes, and you did prove it. You earned a place in the United States military, the most powerful fighting force known to man. You have gained hard-won experience. and you’re making your mark in the military. But, of course, the demands don’t get any lighter. There is no other profession as pressure packed as serving in the armed forces. Some days you love it, I know. And some days you probably ask yourself why you chose this career path.

The good news is that God has you where you are for a reason, and he wants to use you in a way that will amaze even yourself. The pressure and hardship might seem overwhelming at times, but you serve a limitless God. And not only that, you number among the most disciplined and the most highly trained warriors on the planet. Obedience and discipline are keys to success in the military, just as they are in the Christian life and life in general. The lessons you are learning will serve you well for the rest of your life. In Iraq, our military is battling not only the insurgency but also the incredible, stifling heat. It fills the air and radiates from the ground. If you don’t stay hydrated, you can die. First Lieutenant Adam Morehouse, an artillery officer by training, is all too familiar with the deadly desert heat. It can become almost a living thing that crushes the breath out of men and women conducting missions in Iraq. And the demands are mental as well as physical—the pressure can be overwhelming.

Morehouse describes a battalion-sized cordon-and-search missionin a neighborhood near Baghdad, conducted by the Second Infantry Division. His job was to take a team of soldiers and blockoff one of the highways into town. They were going to be sitting along a road, out in the open, for as long as ten hours. Long before the mission was to start, Morehouse racked his sleep-deprived brain: Does everyone know his job? Do we have everything we need? Will we get hit? He collapsed onto his cot, trying to get some rest. His fear was intense. He prayed to God, asking for wisdom and peace. Finally, he drifted off to sleep.

“After I woke up,” he said, “I felt almost a day-and-night change. I felt a complete sense of peace. I’d done everything I could. We were in God’s hands.”

The mission went off without a hitch and without anyone getting hurt. Recently, Morehouse looked back at that experience. “It was the most tangible time in my life that God had directly, instantly, quickly answered a prayer in an obvious way,” he said. Without his faith in God, Lieutenant Morehouse is not sure how he could have handled the pressure. “At every stage of your life you have to make a fresh decision to obey him,” he said. “You can’t make just one decision and coast on it for the rest of your life. You have to decide every day at being obedient to the Lord and work

hard at it. I believe God has me in the Army for a reason, and I trust that he’s still taking care of me. You have to continually seek God’s face.”

Standing Up Under Pressure

The pressure begins the moment you enter basic training. In fact, you feel the force of it as soon as you step off the bus. In my case, it was late, nearly midnight. I’d spent the past five hours on a Greyhound bus traveling from Jacksonville, Florida. We had a short layover in Savannah, Georgia, before pulling out of the bus station, over the towering Savannah bridge and into the night, headed into the South Carolina lowlands. I had only a vague idea of what lay ahead, even though I had volunteered for it. I sat by myself in the dark, watching trees that dripped Spanish moss flash by in the bus’s headlights. As we wound through the back roads, riffs from that summer’s Top 40 hit “Love Will Keep Us Together” kept playing in my mind, crowding out thoughts or doubts before they formed. I didn’t want to think about why I was riding this bus or whether this was what I really wanted to be doing.

There were occasional mileage signs along the way: Hilton Head, 25 miles; Hardeeville, 10 miles; but there were no signs for where we were going. About an hour after the bus left Savannah, we rounded a curve and there it was. A sentry booth guarded the entrance to a long causeway where a large red sign with gold lettering read: Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island, South Carolina. I had arrived.

The driver stopped on the curve and opened the bus’s door with a hiss of escaping air. I joined five other young men getting off the bus, as the passengers bound for Beaufort and points beyond busied themselves with newspapers or buried their faces deeper into makeshift pillows. At the door we were greeted by a puff of warm, humid air that smelled of swamp. We headed toward the sentry booth, where a Marine in blue trousers, khaki shirt, and white garrison cap stood, hands on hips, awaiting our arrival. We sauntered across the road, joking in subdued voices.

“GET OVER HERE—NOW!” he roared.

His voice shook me. The muscles of my legs and buttocks reacted almost involuntarily, as if jolted by a cattle prod. I ran to the gate.

“GET IN LINE! STAND AT ATTENTION!”

We ran to the curb the sentry pointed to, and I fell in at the end of the line. Assuming my best high-school-marching-band position of attention, I remembered not to lock my knees. The sentry didn’t seem to know what to do with us; this apparently was not the usual way for recruits to arrive. They normally came in a full bus and were driven to the receiving barracks on base. He made a phone call, constantly looking toward us as if we were going to run away. He concluded the conversation. “Okay, they’ll be waiting for you.”

The sentry turned to us, his voice only a few decibels lower than when he previously addressed us. “Stand there. A van will be out to pick you up.”

So we stood there in the humid South Carolina night. Meanwhile, cars full of Marines returning from liberty entered the gate. We were pelted with laughs, jeers, you’ll be sorrys. We must have looked ridiculous, standing there at awkward attention in our civilian clothes and long hair. I was disoriented and a bit afraid. I realized later that this was nothing more than the age-old tradition of hazing new members of an elite organization. It was an affirmation of pride; we were the outsiders who had not yet proven our worthiness to belong to their Marine Corps. Soon a van approached the sentry booth, and an avuncular black man in civilian clothing got out and spoke with the sentry. We were told to climb into the van, and I immediately felt a sense of impending judgment. What had I gotten myself into? The driver only added to my confusion. After the gruffness of the sentry, he was friendly and talkative. As we drove down a long causeway lined with palmetto and neatly trimmed shrubbery, he told us that if we had any weapons, particularly knives, we should throw them out the window now before we got to the receiving barracks. On the island, we drove past maintenance buildings and then barracks. Huge steam pipes lined the road, snaking and curving over and around obstacles. On the left was a paved drill field, empty this time of night. The only illumination came from streetlights and stairwell lights in the barracks. We made a right turn, then a left, and stopped outside a twostory white clapboard building. I recognized the sign over the doorway: “Through this portal pass prospects for the world’s finest fighting force.” It struck me as being in the same vein as Dante’s counsel: “All hope abandon, ye who enter here.”

A man in a Smokey Bear hat waited, hands on hips, as the van pulled up. Before one of the other new arrivals could open the van’s door, this man—a drill instructor, otherwise known as a DI—

barked out a Neanderthal sound. I don’t know what he yelled. The mere fact that we were the objects of his wrath jerked us into motion. We tumbled out of the van.

“GET ON THE YELLOW HOOF PRINTS! YOU BETTER HURRY UP.”

I saw a formation of yellow footprints painted on the pavement, but due to my fright or naiveté I looked for yellow horseshoe prints. I finally figured out what he wanted and jumped on the first pair of footprints I saw. I was first in line, so I could see into the door of the barracks. Many other men in civilian clothes, recruits who had arrived earlier that evening, for some reason stood at rigid attention next to tables with silver tops. The DI came up behind me, bending close to my ear.

“Do you see that private in there?” he asked in a menacing voice. The hair stood up on the back of my neck. I didn’t see any private. I couldn’t see anyone in uniform. I hadn’t yet caught on that we were all privates, and the one in question was the man standing closest to the open door. Still, I nodded.

“I want you to go in there and stand at attention next to him,” the DI said. I nodded again, and he grunted out a loud, “MOVE!” I jumped a few inches in the air, as if in a Tex Avery cartoon, and ran up the few steps and into the brightly lit room. Taking a chance, I stopped next to the first man, the private in question. The long room was full of other men standing at attention.

Some already had their heads shaved, although they still wore civilian clothes. A large desk such as you might find in a police station dominated the middle of the room, and several uniformed Marines lounged around it. On the walls of the room were red wooden signs with yellow lettering:

“The first and last word out of your mouth will always be ‘Sir!’” “If you want to use the rest room, you will ask the drill instructor: ‘Sir, Private ____ requests permission to use the head, sir!’”

“You will respond to all orders by sounding off ‘Aye aye, sir!’”

The Marines’ recruiting slogan offers no compromise: “We Don’t Promise You a Rose Garden.”

What Are You After?

For me, this was the culmination of a dream. Okay, it was the beginning of the culmination. One of my earliest memories is as a first-grader sitting at my desk at Hoover Elementary School in Crawfordsville, Indiana, daydreaming about being the youngest member of the Marine Corps, riding to school in the back of a Jeep while wearing the Corps’ Dress Blue uniform, chauffeured by two adult Marines wearing their own snappy Dress Blues. Shortly after that my family moved to Florida, and I played Marine in the surf at the beach, fantasizing amphibious assaults on the sands of the Sunshine State. As a teenager, I devoured books on military history and strategy.

Still, enlisting in the military was not the popular thing to do at the time. America’s involvement in the Vietnam War had officially ended two years earlier, but the situation that spring of 1975 was far from peaceful, and there was fear the United States could be dragged back into the war. Ironically, on the day I signed the dotted line—March 10, 1975—North Vietnam launched a final offensive that would culminate in the fall of South Vietnam in less than two months. My high school friends just couldn’t understand my decision. Why the Marines?

On the surface, a life of rigorous discipline and obedience doesn’t look all that appealing. Some of the strongest natural tendencies inside us rebel at the thought. And at the time I couldn’t put into words why I wanted to join the military. As I look back, though, I realize I wanted to be part of something larger than myself, I wanted adventure, and I wanted to be challenged.

My friend Chuck Holton, a former Army Ranger, was much more articulate about his yearnings as a fifteen-year-old. He wrote in his journal:

There’s so much that I haven’t done that I want to do. So many things I haven’t seen, been to experienced. I’m anxious and excited! What’s God got for me? It’s like I’m standing on the edge of an ocean of possibilities. I can’t see the other side, but I know it’s great. I can’t wait to cross, and I know that although there will always be the peaks and the troughs, every step is an adventure. Life is LIFE! Fill me to overflowing.

Holton had a big advantage over me because he knew God. I did not. But in my case, God was using the Marines as a first step in bringing me to himself. I recognize now that, deep down, my desire to become a Marine was a desire for significance. I needed to do something that mattered. Everyone has a yearning for something bigger than himself. It has been described as the God-shaped hole that we all seek to fill in some way. In his Confessions, Saint Augustine wrote of God, “You have made us for yourself, and our heart is restless until it rests in you.”2 Sometimes, though, filling the restless void can be a lot harder than we imagine. Sometimes God takes us through a wilderness experience to teach us something important. One big reason why is that sometimes the lesson won’t stick any other way.

Learning Discipline in the Wilderness

Moses had to wander on the back side of the desert for forty years before he was prepared for God to use him to confront pharaoh and lead the Hebrews to freedom. Later in the history of Israel,

God chose a shepherd boy, David, to be king of Israel. But David first had to spend months in the wilderness, running from his enemy, Saul, before he was ready to assume the throne. Various Old Testament prophets also had to endure tough times as part of fulfilling God’s purposes. Even Jesus spent forty days fasting in the Judean desert at the beginning of his ministry.

Basic training, in its own way, is like being trained in the wilderness. The process takes us outside ourselves and makes us think in ways we haven’t had to before. It breaks us down so that the military can mold us into men and women who can fulfill a mission. It trains us to be sensitive to orders and to understand the importance of obedience. The biblical figures who were trained by God in the wilderness learned these same lessons. Knowing in the abstract that boot camp will be tough and coming face to face with a tough DI are two entirely different things. I was standing in a room full of frightened recruits being stalked by madmen wearing funny hats. It was late and the heat was sweltering, even at night. Never mind my lifelong dream to be a Marine—I wanted to be anywhere but there. The early days of boot camp, called First Phase, were the hardest. But slowly, gradually, I toughened both physically and mentally. The physical training became a little easier. I was also getting more accustomed to the DIs’ constant demands and the instant obedience they required.

The Power of Individual Discipline

In addition to learning to function as a team in the Marines, we had myriad individual skills to master. Some things we could do only by ourselves, such as fighting with the pugil stick. This training weapon was used to simulate close combat with a rifle. Each stick— pole, really—was about five feet long with large padded ends. In theory, each fight would consist of elegant thrusts and parries, with a clean blow to the head, neck, or upper torso counting as a kill. In reality, the matches quickly degenerated into wild swinging, staggering, and, usually, at least one person flat on his back.

During our platoon’s first session with pugil sticks, I was on one of my periodic spells of light duty for tendonitis. While I was out of commission, the other recruits were shown several tricks for fighting. When we revisited the pugil sticks in Third Phase, all the other recruits had the benefit of at least some experience. I was a rookie. And adding to my sense of dread, the DIs introduced a new wrinkle to the fights: two against one.

We marched as a four-platoon series to the sandy pugil stick pits, where each platoon formed a side of the square. The platoon sat in the grass alongside the pit as instructors conducted quick

refresher training, and then it was time to start. The DIs encouraged us to cheer for fellow platoon members, and the scene soon took on the air of a gladiatorial contest. I was genuinely scared as I awaited my turn. After a few fights—my platoon was losing more than it was winning—one of our DIs, Staff Sergeant Pulley, looked over our platoon. I looked down, as if lack of eye contact would somehow make me invisible. Still, his eyes settled on me. I, who had absolutely no experience with a pugil stick, was chosen to face two opponents.

Weak at the knees and with gargantuan butterflies in my belly, I went to get suited up. As I strapped on the heavy gloves, padded groin protector, and the football helmet with mesh face mask, I was sure I was done for. My heart pounded in my throat as I grasped the pugil stick; it was much heavier than I’d expected. I ventured into the center of the pit, where the referee told me to hold my spot. My two opponents seemed to tower over me. They were ready to put me in a world of hurt. The referee blew the whistle for the match to start, and a passing comment he’d made in the refresher course flashed into my mind: when fighting two or more opponents, keep moving so they can’t come at you two-abreast. That way, one would always be blocked by his partner. I began a rapid sidestep and tried my best to remember the jabs and swings we’d been taught in our close-combat training with the rifle. The sand seemed to grab my feet and hold them, slowing me down. Blows rained down on my arms and shoulders; fortunately none counted as a kill. The fight became a blur of colors and pain, grunts and curses. The rest of the world vanished as I tried desperately to fend off the blows and to make my own feeble counterattack. The stick became heavier, and I soon felt as if I were flailing uselessly. My shoulder muscles burned, my lungs gasped for air, and my legs were turning to jelly as I danced around my opponents in the sand.

Suddenly, the referee’s whistle blew. He motioned to one of my opponents with a slashing motion to the neck, meaning the recruit had been killed. I looked at the referee in disbelief as a roar went

up from my platoon. I’d done that? Pure luck, no doubt. Still, I faced a remaining foe. My arms were growing weaker, my jabs and swings more ineffectual. But my adversary seemed to have slowed even more. He was also looking a bit worried. I was ready to end this thing—NOW! I was seized by a new aggressiveness, and whereas my first kill was probably luck, I found myself aiming a direct slashing blow to his head. My first shot missed, but I was driving him back with a flurry of blows and jabs. Suddenly, the whistle blew again. The referee motioned toward my opponent’s

head—he was out. I triumphantly raised the pugil stick over my head in a scene straight out of Gladiator. My platoon roared its approval. “Nice job, recruit,” the referee said as he helped me strip off the protective gear, and that compliment stoked a fire in my chest. For the first time since arriving at Parris Island, I had a sense of having done something truly significant. Later, in the barracks, I realized my thumb had been seriously smashed despite the protective gloves. I hadn’t felt it during the fight or in the period following. As I stood examining my throbbing digit, lost in thought, Pulley’s voice came from the front of the squad bay.

“If you can move it, it’s not broken.”

I looked up, surprised. He had a slight smile on his face; I sensed he was proud of me. I also sensed he had not expected such an outcome when he chose me, considering I was not the most studly recruit in the platoon. (I’m six-one now, but the last four of those inches came in a final growth spurt after boot camp.) Maybe when he sent me into the sand pit he sensed I was capable of more. I’ll never know.

Following God in the Military

Looking back, I realize it doesn’t matter what was behind the DI’s decision to send me up against two armed opponents. Serving in uniform means you will be asked to do things you’re sure you are not capable of. And then, after plunging in, you find that you are capable of much more than you thought. As someone has said, “God does not call the qualified; he qualifies the called.”

It’s a good thing God is involved in our training, because without his help in overcoming our lower nature we’d be hard pressed to develop the discipline and obedience necessary to succeed in the military. As you well know, these are two of the hardest things in life to master, and it’s not because of laziness or a secret desire to fail. It’s because we are born with a sin nature that automatically rebels whenever we are told what to do by a higher authority (see Genesis 3:1, 4, 6). Human nature is referred to in the New Testament as the “old self” (see Colossians 3:9).

Our original nature, which remains active even after we become Christians, wars against our new nature, given to us by Christ (see 2 Corinthians 5:17; Romans 7:15–25). The conflict between the two comes out in everyday life, whether you’re a civilian or in uniform. But in the pressure cooker of military life, you could rightly say the war between our old nature and our new nature assumes biblical proportions. Living up to the expectations of our DIs in boot camp was hard. Living up to the life God calls us to is much harder.

Thankfully, we’re not alone in this struggle. Think about the task set before Moses. God called him to take on the most powerful man in the world, the pharaoh of Egypt, and to demand that pharaoh free the Hebrew slaves. Moses was, quite understandably, afraid. He was also uncertain of his own abilities. In fact, he made sure God was aware of his many deficiencies. “Moses said to the LORD, ‘O Lord, I have never been eloquent, neither in the past nor since you have spoken to your servant. I am slow of speech and tongue’” (Exodus 4:10). But God would have none of it. “The LORD said to him, ‘Who gave man his mouth? Who makes him deaf or mute? Who gives him sight or makes him blind? Is it not I, the LORD? Now go; I will help you speak and will teach you what

to say’” (Exodus 4:11–12). Unlike the ancient warriors of God, we will not stand face to face in opposition to the world’s most powerful king, as Moses did, or face a giant, as the boy David did. Instead, in light of today’s wars, you might face insurgents who easily blend into the crowd.

Every pothole in the road and every piece of trash might be a vehicle-destroying bomb. You might be caught in the middle of warring factions, countrymen who can’t seem to settle their differences

without resorting to arms. In fulfilling your mission, you might also have to fight discouragement. What will it take to bring about good in a land that seems intent on thwarting all attempts to restore peace and order? If you are serving in Iraq or Afghanistan, you are putting your life on the line to help a country in turmoil, and the solutions are far from simple.

You know already that in the military, the pressure doesn’t let up. The demands are constant and often seem to require superhuman strength and wisdom. And in a sense, they do require that level of strength and wisdom. It’s a good thing you have God as a guide. Just as God directed David, Moses, and other warriors in ancient times, he stands ready to help you today.

Colonel Paul Meredith, who recently retired after twentyseven years in the Army, stressed that you cannot be passive in seeking God’s help. “You have to be proactive to nurture your faith,” he said. “Soldiers have a lot of discretionary time. You have to choose to build a discipleship group, to seek an accountability partner, to find the chaplain and let him know who you are and that you’re a believer. “Always get involved in a prayer group,” he added. “These have been the best, the closest relationships I ever had in the Army. Those are the guys who are your closest friends."

The good news is that God has you where you are for a reason, and he wants to use you in a way that will amaze even yourself. The pressure and hardship might seem overwhelming at times, but you serve a limitless God. And not only that, you number among the most disciplined and the most highly trained warriors on the planet. Obedience and discipline are keys to success in the military, just as they are in the Christian life and life in general. The lessons you are learning will serve you well for the rest of your life. In Iraq, our military is battling not only the insurgency but also the incredible, stifling heat. It fills the air and radiates from the ground. If you don’t stay hydrated, you can die. First Lieutenant Adam Morehouse, an artillery officer by training, is all too familiar with the deadly desert heat. It can become almost a living thing that crushes the breath out of men and women conducting missions in Iraq. And the demands are mental as well as physical—the pressure can be overwhelming.

Morehouse describes a battalion-sized cordon-and-search missionin a neighborhood near Baghdad, conducted by the Second Infantry Division. His job was to take a team of soldiers and blockoff one of the highways into town. They were going to be sitting along a road, out in the open, for as long as ten hours. Long before the mission was to start, Morehouse racked his sleep-deprived brain: Does everyone know his job? Do we have everything we need? Will we get hit? He collapsed onto his cot, trying to get some rest. His fear was intense. He prayed to God, asking for wisdom and peace. Finally, he drifted off to sleep.

“After I woke up,” he said, “I felt almost a day-and-night change. I felt a complete sense of peace. I’d done everything I could. We were in God’s hands.”

The mission went off without a hitch and without anyone getting hurt. Recently, Morehouse looked back at that experience. “It was the most tangible time in my life that God had directly, instantly, quickly answered a prayer in an obvious way,” he said. Without his faith in God, Lieutenant Morehouse is not sure how he could have handled the pressure. “At every stage of your life you have to make a fresh decision to obey him,” he said. “You can’t make just one decision and coast on it for the rest of your life. You have to decide every day at being obedient to the Lord and work

hard at it. I believe God has me in the Army for a reason, and I trust that he’s still taking care of me. You have to continually seek God’s face.”

Standing Up Under Pressure

The pressure begins the moment you enter basic training. In fact, you feel the force of it as soon as you step off the bus. In my case, it was late, nearly midnight. I’d spent the past five hours on a Greyhound bus traveling from Jacksonville, Florida. We had a short layover in Savannah, Georgia, before pulling out of the bus station, over the towering Savannah bridge and into the night, headed into the South Carolina lowlands. I had only a vague idea of what lay ahead, even though I had volunteered for it. I sat by myself in the dark, watching trees that dripped Spanish moss flash by in the bus’s headlights. As we wound through the back roads, riffs from that summer’s Top 40 hit “Love Will Keep Us Together” kept playing in my mind, crowding out thoughts or doubts before they formed. I didn’t want to think about why I was riding this bus or whether this was what I really wanted to be doing.

There were occasional mileage signs along the way: Hilton Head, 25 miles; Hardeeville, 10 miles; but there were no signs for where we were going. About an hour after the bus left Savannah, we rounded a curve and there it was. A sentry booth guarded the entrance to a long causeway where a large red sign with gold lettering read: Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island, South Carolina. I had arrived.

The driver stopped on the curve and opened the bus’s door with a hiss of escaping air. I joined five other young men getting off the bus, as the passengers bound for Beaufort and points beyond busied themselves with newspapers or buried their faces deeper into makeshift pillows. At the door we were greeted by a puff of warm, humid air that smelled of swamp. We headed toward the sentry booth, where a Marine in blue trousers, khaki shirt, and white garrison cap stood, hands on hips, awaiting our arrival. We sauntered across the road, joking in subdued voices.

“GET OVER HERE—NOW!” he roared.

His voice shook me. The muscles of my legs and buttocks reacted almost involuntarily, as if jolted by a cattle prod. I ran to the gate.

“GET IN LINE! STAND AT ATTENTION!”

We ran to the curb the sentry pointed to, and I fell in at the end of the line. Assuming my best high-school-marching-band position of attention, I remembered not to lock my knees. The sentry didn’t seem to know what to do with us; this apparently was not the usual way for recruits to arrive. They normally came in a full bus and were driven to the receiving barracks on base. He made a phone call, constantly looking toward us as if we were going to run away. He concluded the conversation. “Okay, they’ll be waiting for you.”

The sentry turned to us, his voice only a few decibels lower than when he previously addressed us. “Stand there. A van will be out to pick you up.”

So we stood there in the humid South Carolina night. Meanwhile, cars full of Marines returning from liberty entered the gate. We were pelted with laughs, jeers, you’ll be sorrys. We must have looked ridiculous, standing there at awkward attention in our civilian clothes and long hair. I was disoriented and a bit afraid. I realized later that this was nothing more than the age-old tradition of hazing new members of an elite organization. It was an affirmation of pride; we were the outsiders who had not yet proven our worthiness to belong to their Marine Corps. Soon a van approached the sentry booth, and an avuncular black man in civilian clothing got out and spoke with the sentry. We were told to climb into the van, and I immediately felt a sense of impending judgment. What had I gotten myself into? The driver only added to my confusion. After the gruffness of the sentry, he was friendly and talkative. As we drove down a long causeway lined with palmetto and neatly trimmed shrubbery, he told us that if we had any weapons, particularly knives, we should throw them out the window now before we got to the receiving barracks. On the island, we drove past maintenance buildings and then barracks. Huge steam pipes lined the road, snaking and curving over and around obstacles. On the left was a paved drill field, empty this time of night. The only illumination came from streetlights and stairwell lights in the barracks. We made a right turn, then a left, and stopped outside a twostory white clapboard building. I recognized the sign over the doorway: “Through this portal pass prospects for the world’s finest fighting force.” It struck me as being in the same vein as Dante’s counsel: “All hope abandon, ye who enter here.”

A man in a Smokey Bear hat waited, hands on hips, as the van pulled up. Before one of the other new arrivals could open the van’s door, this man—a drill instructor, otherwise known as a DI—

barked out a Neanderthal sound. I don’t know what he yelled. The mere fact that we were the objects of his wrath jerked us into motion. We tumbled out of the van.

“GET ON THE YELLOW HOOF PRINTS! YOU BETTER HURRY UP.”

I saw a formation of yellow footprints painted on the pavement, but due to my fright or naiveté I looked for yellow horseshoe prints. I finally figured out what he wanted and jumped on the first pair of footprints I saw. I was first in line, so I could see into the door of the barracks. Many other men in civilian clothes, recruits who had arrived earlier that evening, for some reason stood at rigid attention next to tables with silver tops. The DI came up behind me, bending close to my ear.

“Do you see that private in there?” he asked in a menacing voice. The hair stood up on the back of my neck. I didn’t see any private. I couldn’t see anyone in uniform. I hadn’t yet caught on that we were all privates, and the one in question was the man standing closest to the open door. Still, I nodded.

“I want you to go in there and stand at attention next to him,” the DI said. I nodded again, and he grunted out a loud, “MOVE!” I jumped a few inches in the air, as if in a Tex Avery cartoon, and ran up the few steps and into the brightly lit room. Taking a chance, I stopped next to the first man, the private in question. The long room was full of other men standing at attention.

Some already had their heads shaved, although they still wore civilian clothes. A large desk such as you might find in a police station dominated the middle of the room, and several uniformed Marines lounged around it. On the walls of the room were red wooden signs with yellow lettering:

“The first and last word out of your mouth will always be ‘Sir!’” “If you want to use the rest room, you will ask the drill instructor: ‘Sir, Private ____ requests permission to use the head, sir!’”

“You will respond to all orders by sounding off ‘Aye aye, sir!’”

The Marines’ recruiting slogan offers no compromise: “We Don’t Promise You a Rose Garden.”

What Are You After?

For me, this was the culmination of a dream. Okay, it was the beginning of the culmination. One of my earliest memories is as a first-grader sitting at my desk at Hoover Elementary School in Crawfordsville, Indiana, daydreaming about being the youngest member of the Marine Corps, riding to school in the back of a Jeep while wearing the Corps’ Dress Blue uniform, chauffeured by two adult Marines wearing their own snappy Dress Blues. Shortly after that my family moved to Florida, and I played Marine in the surf at the beach, fantasizing amphibious assaults on the sands of the Sunshine State. As a teenager, I devoured books on military history and strategy.

Still, enlisting in the military was not the popular thing to do at the time. America’s involvement in the Vietnam War had officially ended two years earlier, but the situation that spring of 1975 was far from peaceful, and there was fear the United States could be dragged back into the war. Ironically, on the day I signed the dotted line—March 10, 1975—North Vietnam launched a final offensive that would culminate in the fall of South Vietnam in less than two months. My high school friends just couldn’t understand my decision. Why the Marines?

On the surface, a life of rigorous discipline and obedience doesn’t look all that appealing. Some of the strongest natural tendencies inside us rebel at the thought. And at the time I couldn’t put into words why I wanted to join the military. As I look back, though, I realize I wanted to be part of something larger than myself, I wanted adventure, and I wanted to be challenged.

My friend Chuck Holton, a former Army Ranger, was much more articulate about his yearnings as a fifteen-year-old. He wrote in his journal:

There’s so much that I haven’t done that I want to do. So many things I haven’t seen, been to experienced. I’m anxious and excited! What’s God got for me? It’s like I’m standing on the edge of an ocean of possibilities. I can’t see the other side, but I know it’s great. I can’t wait to cross, and I know that although there will always be the peaks and the troughs, every step is an adventure. Life is LIFE! Fill me to overflowing.

Holton had a big advantage over me because he knew God. I did not. But in my case, God was using the Marines as a first step in bringing me to himself. I recognize now that, deep down, my desire to become a Marine was a desire for significance. I needed to do something that mattered. Everyone has a yearning for something bigger than himself. It has been described as the God-shaped hole that we all seek to fill in some way. In his Confessions, Saint Augustine wrote of God, “You have made us for yourself, and our heart is restless until it rests in you.”2 Sometimes, though, filling the restless void can be a lot harder than we imagine. Sometimes God takes us through a wilderness experience to teach us something important. One big reason why is that sometimes the lesson won’t stick any other way.

Learning Discipline in the Wilderness

Moses had to wander on the back side of the desert for forty years before he was prepared for God to use him to confront pharaoh and lead the Hebrews to freedom. Later in the history of Israel,

God chose a shepherd boy, David, to be king of Israel. But David first had to spend months in the wilderness, running from his enemy, Saul, before he was ready to assume the throne. Various Old Testament prophets also had to endure tough times as part of fulfilling God’s purposes. Even Jesus spent forty days fasting in the Judean desert at the beginning of his ministry.

Basic training, in its own way, is like being trained in the wilderness. The process takes us outside ourselves and makes us think in ways we haven’t had to before. It breaks us down so that the military can mold us into men and women who can fulfill a mission. It trains us to be sensitive to orders and to understand the importance of obedience. The biblical figures who were trained by God in the wilderness learned these same lessons. Knowing in the abstract that boot camp will be tough and coming face to face with a tough DI are two entirely different things. I was standing in a room full of frightened recruits being stalked by madmen wearing funny hats. It was late and the heat was sweltering, even at night. Never mind my lifelong dream to be a Marine—I wanted to be anywhere but there. The early days of boot camp, called First Phase, were the hardest. But slowly, gradually, I toughened both physically and mentally. The physical training became a little easier. I was also getting more accustomed to the DIs’ constant demands and the instant obedience they required.

The Power of Individual Discipline

In addition to learning to function as a team in the Marines, we had myriad individual skills to master. Some things we could do only by ourselves, such as fighting with the pugil stick. This training weapon was used to simulate close combat with a rifle. Each stick— pole, really—was about five feet long with large padded ends. In theory, each fight would consist of elegant thrusts and parries, with a clean blow to the head, neck, or upper torso counting as a kill. In reality, the matches quickly degenerated into wild swinging, staggering, and, usually, at least one person flat on his back.

During our platoon’s first session with pugil sticks, I was on one of my periodic spells of light duty for tendonitis. While I was out of commission, the other recruits were shown several tricks for fighting. When we revisited the pugil sticks in Third Phase, all the other recruits had the benefit of at least some experience. I was a rookie. And adding to my sense of dread, the DIs introduced a new wrinkle to the fights: two against one.

We marched as a four-platoon series to the sandy pugil stick pits, where each platoon formed a side of the square. The platoon sat in the grass alongside the pit as instructors conducted quick

refresher training, and then it was time to start. The DIs encouraged us to cheer for fellow platoon members, and the scene soon took on the air of a gladiatorial contest. I was genuinely scared as I awaited my turn. After a few fights—my platoon was losing more than it was winning—one of our DIs, Staff Sergeant Pulley, looked over our platoon. I looked down, as if lack of eye contact would somehow make me invisible. Still, his eyes settled on me. I, who had absolutely no experience with a pugil stick, was chosen to face two opponents.

Weak at the knees and with gargantuan butterflies in my belly, I went to get suited up. As I strapped on the heavy gloves, padded groin protector, and the football helmet with mesh face mask, I was sure I was done for. My heart pounded in my throat as I grasped the pugil stick; it was much heavier than I’d expected. I ventured into the center of the pit, where the referee told me to hold my spot. My two opponents seemed to tower over me. They were ready to put me in a world of hurt. The referee blew the whistle for the match to start, and a passing comment he’d made in the refresher course flashed into my mind: when fighting two or more opponents, keep moving so they can’t come at you two-abreast. That way, one would always be blocked by his partner. I began a rapid sidestep and tried my best to remember the jabs and swings we’d been taught in our close-combat training with the rifle. The sand seemed to grab my feet and hold them, slowing me down. Blows rained down on my arms and shoulders; fortunately none counted as a kill. The fight became a blur of colors and pain, grunts and curses. The rest of the world vanished as I tried desperately to fend off the blows and to make my own feeble counterattack. The stick became heavier, and I soon felt as if I were flailing uselessly. My shoulder muscles burned, my lungs gasped for air, and my legs were turning to jelly as I danced around my opponents in the sand.

Suddenly, the referee’s whistle blew. He motioned to one of my opponents with a slashing motion to the neck, meaning the recruit had been killed. I looked at the referee in disbelief as a roar went

up from my platoon. I’d done that? Pure luck, no doubt. Still, I faced a remaining foe. My arms were growing weaker, my jabs and swings more ineffectual. But my adversary seemed to have slowed even more. He was also looking a bit worried. I was ready to end this thing—NOW! I was seized by a new aggressiveness, and whereas my first kill was probably luck, I found myself aiming a direct slashing blow to his head. My first shot missed, but I was driving him back with a flurry of blows and jabs. Suddenly, the whistle blew again. The referee motioned toward my opponent’s

head—he was out. I triumphantly raised the pugil stick over my head in a scene straight out of Gladiator. My platoon roared its approval. “Nice job, recruit,” the referee said as he helped me strip off the protective gear, and that compliment stoked a fire in my chest. For the first time since arriving at Parris Island, I had a sense of having done something truly significant. Later, in the barracks, I realized my thumb had been seriously smashed despite the protective gloves. I hadn’t felt it during the fight or in the period following. As I stood examining my throbbing digit, lost in thought, Pulley’s voice came from the front of the squad bay.

“If you can move it, it’s not broken.”

I looked up, surprised. He had a slight smile on his face; I sensed he was proud of me. I also sensed he had not expected such an outcome when he chose me, considering I was not the most studly recruit in the platoon. (I’m six-one now, but the last four of those inches came in a final growth spurt after boot camp.) Maybe when he sent me into the sand pit he sensed I was capable of more. I’ll never know.

Following God in the Military

Looking back, I realize it doesn’t matter what was behind the DI’s decision to send me up against two armed opponents. Serving in uniform means you will be asked to do things you’re sure you are not capable of. And then, after plunging in, you find that you are capable of much more than you thought. As someone has said, “God does not call the qualified; he qualifies the called.”

It’s a good thing God is involved in our training, because without his help in overcoming our lower nature we’d be hard pressed to develop the discipline and obedience necessary to succeed in the military. As you well know, these are two of the hardest things in life to master, and it’s not because of laziness or a secret desire to fail. It’s because we are born with a sin nature that automatically rebels whenever we are told what to do by a higher authority (see Genesis 3:1, 4, 6). Human nature is referred to in the New Testament as the “old self” (see Colossians 3:9).

Our original nature, which remains active even after we become Christians, wars against our new nature, given to us by Christ (see 2 Corinthians 5:17; Romans 7:15–25). The conflict between the two comes out in everyday life, whether you’re a civilian or in uniform. But in the pressure cooker of military life, you could rightly say the war between our old nature and our new nature assumes biblical proportions. Living up to the expectations of our DIs in boot camp was hard. Living up to the life God calls us to is much harder.

Thankfully, we’re not alone in this struggle. Think about the task set before Moses. God called him to take on the most powerful man in the world, the pharaoh of Egypt, and to demand that pharaoh free the Hebrew slaves. Moses was, quite understandably, afraid. He was also uncertain of his own abilities. In fact, he made sure God was aware of his many deficiencies. “Moses said to the LORD, ‘O Lord, I have never been eloquent, neither in the past nor since you have spoken to your servant. I am slow of speech and tongue’” (Exodus 4:10). But God would have none of it. “The LORD said to him, ‘Who gave man his mouth? Who makes him deaf or mute? Who gives him sight or makes him blind? Is it not I, the LORD? Now go; I will help you speak and will teach you what

to say’” (Exodus 4:11–12). Unlike the ancient warriors of God, we will not stand face to face in opposition to the world’s most powerful king, as Moses did, or face a giant, as the boy David did. Instead, in light of today’s wars, you might face insurgents who easily blend into the crowd.

Every pothole in the road and every piece of trash might be a vehicle-destroying bomb. You might be caught in the middle of warring factions, countrymen who can’t seem to settle their differences

without resorting to arms. In fulfilling your mission, you might also have to fight discouragement. What will it take to bring about good in a land that seems intent on thwarting all attempts to restore peace and order? If you are serving in Iraq or Afghanistan, you are putting your life on the line to help a country in turmoil, and the solutions are far from simple.

You know already that in the military, the pressure doesn’t let up. The demands are constant and often seem to require superhuman strength and wisdom. And in a sense, they do require that level of strength and wisdom. It’s a good thing you have God as a guide. Just as God directed David, Moses, and other warriors in ancient times, he stands ready to help you today.

Colonel Paul Meredith, who recently retired after twentyseven years in the Army, stressed that you cannot be passive in seeking God’s help. “You have to be proactive to nurture your faith,” he said. “Soldiers have a lot of discretionary time. You have to choose to build a discipleship group, to seek an accountability partner, to find the chaplain and let him know who you are and that you’re a believer. “Always get involved in a prayer group,” he added. “These have been the best, the closest relationships I ever had in the Army. Those are the guys who are your closest friends."

Recenzii

Praise for On the Frontline

“No tactical field manual will help you when the bullets are flying if you don’t have your head on straight, and that is where On the Frontline comes in. Read it. Take it to heart. You’ll be glad you did.”

–Chuck Holton, author, Army Ranger, and CBN Adventure Correspondent

“God’s word and On the Frontline are a must in order to lead a complete and victorious life as a Christian warrior. Don’t deploy without Tom Neven’s operational manual on Christian living in the military!”

–Lt. General Bruce L. Fister, USAF (retired), Executive Director of Officers’ Christian Fellowship of the USA

“Tom Neven offers clear and concise answers to the questions and concerns that plague military members and their families. This book needs to be on every frontline reading list of military members from every branch of the service.”

– Ellie Kay, best-selling author of Heroes at Home and keynote speaker for the Heroes at Home World Tour

“If you’re looking for God’s answers to man’s dilemmas, this book is a great tool–particularly for the men and women on America’s frontlines.”

–Colonel Jeff O’Leary, USAF (retired), Fox News Military Analyst

“Tom Neven steels the heart and soul for the warfare, both worldly and spiritual, that awaits the warrior. Neven speaks with the wisdom and authority of a scout who has walked the trail and knows how to get to the objective without falling prey to the enemy.”

–Lt. Colonel Gary Walsh, U.S. Army (retired), Infantry and Legal Officer who served combat tours in Grenada and Somalia

“No tactical field manual will help you when the bullets are flying if you don’t have your head on straight, and that is where On the Frontline comes in. Read it. Take it to heart. You’ll be glad you did.”

–Chuck Holton, author, Army Ranger, and CBN Adventure Correspondent

“God’s word and On the Frontline are a must in order to lead a complete and victorious life as a Christian warrior. Don’t deploy without Tom Neven’s operational manual on Christian living in the military!”

–Lt. General Bruce L. Fister, USAF (retired), Executive Director of Officers’ Christian Fellowship of the USA

“Tom Neven offers clear and concise answers to the questions and concerns that plague military members and their families. This book needs to be on every frontline reading list of military members from every branch of the service.”

– Ellie Kay, best-selling author of Heroes at Home and keynote speaker for the Heroes at Home World Tour

“If you’re looking for God’s answers to man’s dilemmas, this book is a great tool–particularly for the men and women on America’s frontlines.”

–Colonel Jeff O’Leary, USAF (retired), Fox News Military Analyst

“Tom Neven steels the heart and soul for the warfare, both worldly and spiritual, that awaits the warrior. Neven speaks with the wisdom and authority of a scout who has walked the trail and knows how to get to the objective without falling prey to the enemy.”

–Lt. Colonel Gary Walsh, U.S. Army (retired), Infantry and Legal Officer who served combat tours in Grenada and Somalia

Descriere

This powerful book for men and women uses examples from history, real-life anecdotes, and biblical wisdom to help readers navigate the biggest challenges of military life. Neven confronts such issues as stress, depression, loneliness, and other issues, offering hope, encouragement, and practical guidance.