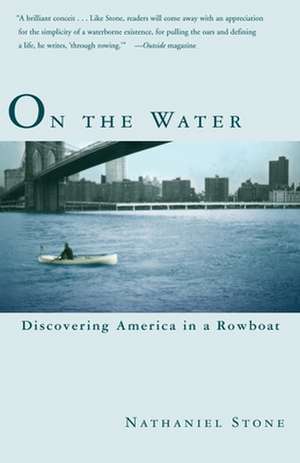

On the Water: Discovering America in a Row Boat

Autor Nathaniel Stoneen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2003

Few people have ever considered the eastern United States to be an island, but when Nat Stone began tracing waterways in his new atlas at the age of ten he discovered that if one had a boat it was possible to use a combination of waterways to travel up the Hudson River, west across the barge canals and the Great Lakes, down the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico, and back up the eastern seaboard. Years later, still fascinated by the idea of the island, Stone read a biography of Howard Blackburn, a nineteenth-century Gloucester fisherman who had attempted to sail the same route a century before. Stone decided he would row rather than sail, and in April 1999 he launched a scull beneath the Brooklyn Bridge to see how far he could get. After ten months and some six thousand miles he arrived back at the Brooklyn Bridge, and continued rowing on to Eastport, Maine.

Retracing Stone’s extraordinary voyage, On the Water is a marvelous portrait of the vibrant cultures inhabiting American shores and the magic of a traveler’s chance encounters. From Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where a rower at the local boathouse bequeaths him a pair of fabled oars, to Vanceburg, Kentucky, where he spends a day fishing with Ed Taylor -- a man whose efficient simplicity recalls The Old Man and the Sea -- Stone makes his way, stroke by stroke, chatting with tugboat operators and sleeping in his boat under the stars. He listens to the live strains of Dwight Yoakum on the banks of the Ohio while the world’s largest Superman statue guards the nearby town square, and winds his way through the Louisiana bayous, where he befriends Scoober, an old man who reminds him that the happiest people are those who’ve “got nothin’.” He briefly adopts a rowing companion -- a kitten -- along the west coast of Florida, and finds himself stuck in the tidal mudflats of Georgia. Along the way, he flavors his narrative with local history and lore and records the evolution of what started out as an adventure but became a lifestyle.

An extraordinary literary debut in the lyrical, timeless style of William Least Heat-Moon and Henry David Thoreau, On the Water is a mariner’s tribute to childhood dreams, solitary journeys, and the transformative powers of America’s rivers, lakes, and coastlines.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 115.10 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 173

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.03€ • 23.92$ • 18.50£

22.03€ • 23.92$ • 18.50£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 02-16 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767908429

ISBN-10: 0767908422

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 141 x 217 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.42 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0767908422

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 141 x 217 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.42 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

Nathaniel Stone grew up in Marblehead, Massachusetts. He taught tenth grade history in Pasadena, California, and Zuni, New Mexico, where he founded the local newspaper and currently resides.

www.natstone.com

From the Hardcover edition.

www.natstone.com

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

1

A Perceptible Wake

"What street are we at?" I call up to a jogger who's been watching as my strokes against the river's current overtake his strides along the promenade. He glances to his left, where one of the lesser architectural canyons of Manhattan is marked by a street sign just out of my view.

"One-hundred-and-tenth Street," he reports. A moment of silence as we acknowledge each other in self-propulsion.

"How far are you going?"

I search the riverscape briefly, then look back to him: "Bourbon Street!"

A blank look. He carries his momentum through a few more strides while I take a couple of strokes. And then suddenly he smiles and punches a fist up into the air.

It is spring on the Harlem River. As I row northward, people fishing from the granite seawall cast their lures and hooks on silken strands that sing out across the water. The way the weighted barbs arc across the blue April sky you'd think the aim, spiderlike, was for the opposing shore of the Bronx. Then, reels spent, they lose their flight and softly plunge into brown, working water, and the slackened filaments follow, sighing across the river's surface. There are others too, families and friends, who sit on city benches, talking and laughing, or reading, or with their eyes closed and faces tilted up to the spring-warm sun. Some lean against the green metal railing with their forearms, hands clasped, looking down at the river, or beyond the river to the Bronx, or, as I pass by, at me. Young children wave to me through the bars of the railing. One boy is too tall to look below the handrail, but too short to look above. He stretches his legs for the upper view, then stoops for the lower and waves. Some call out to ask where I'm going, and I tell them "New Orleans!" or "the Gulf of Mexico!" One man with a thick city accent corrects me, pointing south: "You're goin' the wrong way, man! New Orleans is that way!" He won't be the last to say so as I proceed up the Hudson toward Albany, and west along the Erie Canal toward Buffalo, five hundred miles of rowing without an inch gained toward the gulf before finally swinging the bow southward toward the land of the Cajuns.

Already the palms of my hands have opened up to the deepest layers of skin. Two months before setting out I started training on a rowing machine in hopes of building my calluses, but the machine doesn't mimic the feathering of the oars, and any toughness I had has been blistered, ruptured, then slowly worn away as if the trip itself has had a word with me: "Now let me show you what I meant by calluses." The chafing is exacerbated by the rubber grips of my secondhand oars. The parallel fine ridges of rubber tread, presumably once soft, have been hardened by exposure to the sun and slowly pare my hands to their epidermal base. Yet just two weeks and 140 miles from here, at Watervliet, near Albany, I will be given a piece of 80-grit sandpaper with which I'll scour smooth the ridges of my leathered palms.

"What possessed you?"

A question I was frequently asked over six thousand miles of rowing. The phrasing rarely wavered, and the verb choice was consistent. It's enough to say that I'm possessed by a love for water and by a fascination with boats. Had I been raised in farm country I might have ridden a horse from Butte to Bar Harbor, but I grew up along the coast of Massachusetts, and the first boat I was ever in by myself was an inflatable dinghy with the wooden oars of a skiff. It was the summer of 1975 and I was seven years old, and I still remember my newfound sense of independence as I struggled to coordinate the two unwieldy oars through the translucent cold below. Two snapshots were taken of me that day. In the first, preserved in the family photo album, I am seated, oars idle in the oarlocks, blades in the water, grinning at the camera and with arms raised in a cheer. In the second picture, with oars not quite synchronized but leaving a perceptible wake, I am rowing away.

Add to my love affair with boats and water a passion for geography. I spent uncounted hours as a child poring through the family atlas, distracted from the center of the universe that was my hometown by the idea that someone, at the same moment, was living in such exotic outbacks as the Zuni Indian Reservation in New Mexico, or along the simple crosshairs of Leola, South Dakota, or at the end of the dead-end road to Candelaria, West Texas. At some point, when I was perhaps ten, while studying the Mississippi River, the Great Lakes, and their outlet down the St. Lawrence to the sea, it occurred to me that the right combination of blue watery veins on the atlas maps might provide a narrow yet unbroken channel between the North Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico. From Lake Erie I traced the dead-end Sandusky, and eyed the Maumee River, which very nearly kisses the Wabash, a tributary of the Ohio. To the east, heading inland from Lake Ontario, the Genesee's shared geological roots with the Allegheny tempted me. I discovered, though, that they too are divided, with headwaters some five miles apart, as one drains toward the Atlantic and the other toward the Gulf of Mexico. Just cousins.

I traced west through the pages of the atlas, past, for my purposes, riverless Michigan and Indiana, and arrived by finger at Chicago. There I discovered I'd been right to mount the quest, for parallel to both the Adlai E. Stevenson Expressway and the partly filled Illinois and Michigan Canal runs the thirty-mile thread of the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal. Though I imagined a gapingly wide sewage gutter plied by oceangoing ships with foreign flags, a canal is a canal, and by Joliet, heading south, it becomes the Illinois River, bound for the Mississippi. Despite this technicality of American engineering, and with Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and a bit of Quebec included, I've thought of the eastern United States as an island ever since.

A final seed of motivation was planted shortly after the day of my college graduation when, as I bade farewell to extended youth, I was diagnosed with chicken pox. While friends celebrated and planned their next steps, I sat at home for three weeks, let my whiskers grow into a beard I was not allowed to scratch, and read. I became immersed in Lone Voyager, Joseph Garland's biography of Howard Blackburn, a late-nineteenth-century Gloucester fisherman. While fishing for halibut in January on Newfoundland's Burgeo Bank, Blackburn and his dory mate, Thomas Welch, were separated from their mother schooner, the Grace L. Fears, by a blizzard. When the blizzard gave way to night and a cloudless gale, the two could see the lantern lights of the schooner on the windward horizon, but they were unable to row their lumbering dory against the waves. By morning they had been blown out of sight of the Grace L. Fears.

The two men took turns bailing for their lives as the gale continued, and in doing so inadvertently bailed from the boat Blackburn's woolen mittens, which he'd tossed into the salty bilge to keep them from freezing solid while he worked. Soon as Welsh weakened in the cold, Howard's fingers grew frostbitten and useless. With rowing for the coast his only hope, he forced his fingers around the handles of the oars. In twenty minutes they were frozen claws.

On the second night, with the gale unabated, Thomas Welch died of exposure. With his frozen partner as company and ballast, Blackburn managed to continue bailing with his lifeless hands. At dawn of the third day the wind eased and he started rowing north toward the coast of Newfoundland, some sixty miles away. For two days and a night Blackburn continued on, his fingers worn bare to the bone on the wooden handles of the oars.

Amazingly, Blackburn reached the desolate coast, and happened to find an abandoned, roofless shack in which he spent a night fighting his lethal desire for sleep. The following day, after attempting to remove Welch's corpse from the boat and losing it to the salty depths, Blackburn set out again in his dory and headed west along the rugged coast in search of help. On the fifth night after Howard Blackburn and Thomas Welch were lost on the wintry sea, Blackburn was rescued when he landed near a settlement of impoverished fishermen, who over the following months nursed him to digitless health.

After returning to fame in Gloucester and a venture as a successful tavern owner, Blackburn grew restless and taught himself to sail despite the limited usefulness of his hands. After several solo transatlantic crossings in smaller and smaller boats, he embarked in 1902 on a circumnavigation of the eastern United States by sail. He cruised his gaff-rigged sloop, Great Republic, up the Hudson River, towed his boat from the footpath the length of the Erie Canal, and then sailed the Great Lakes to Chicago. Eight decades before I had stumbled across it in an atlas, Blackburn traveled the Illinois and Michigan Canal to the Illinois River, and was soon headed down the Mississippi for the Gulf of Mexico.

Upon rounding Florida and reaching Miami, Blackburn had nearly had enough. Among other obstacles, his deep-draft vessel had regularly encountered the shallow depths of Mississippi sandbars and the shoals of the Gulf coast. After running hard aground near Miami, he sold Great Republic and with characteristic obstinacy replaced it with a twelve-foot rowing boat. Blackburn managed, with a leather strap around each wrist, to row another two hundred miles up the coast of Florida, at which point he'd had fully enough, and took a steamer back to New England.

Yet Blackburn had thought of the island too. I was entranced. I pulled out my road atlas, with its detailed representation of American rivers--the book most often by my side--and studied the route and possible alternatives. By the time I had finished Lone Voyager I'd decided that the ideal nonmotorized vessel, for its shallow draft, carrying capacity, and ability to progress in wind or calm, was a rowing boat. And over the following seven years, years spent discouragingly far from navigable water, my bedtime reading was often from the atlas. I wondered how many miles I could row in a day, and for how many days on end.

I had plain adventure in mind, to be sure. I imagined camping along riverbanks, dodging coal barges, and simply being in a boat on the water. But there was more to it than boyhood fantasy, and it's not enough just to add that I wanted the physical challenge. Over a period of several years, in a recurring dream of descent into darkness, I found myself following narrow, wooden, rickety stairs, dimly lit, perhaps by a hanging bulb, to a musty cellar, which in turn led through a trapdoor or some gaping hole to other stairs and other cellars, one below another. In variations of the dream I followed tunnels borrowed from Edgar Allan Poe--ever constricting but not dead-ending--or ventured into darkened water through which I dived headlong, uncertain whether the bottom was feet or fathoms below. Sometimes I carried a light that emitted a murky glow, then died. Other times I had enough light only to say the darkness was not absolute.

The dreams were tense, yet void of fear. I was not running from anything, but was being drawn toward some unknown, in cellars and tunnels and oceans never fully plumbed. To me, they suggested an inner search for something more, perhaps, for something richer, more off-centering than what my everyday, familiar routines allowed. It was true, I'd been treading water, wondering what was next, and waking up in the morning had become more of a habit than an opportunity. Days were becoming forgettable; they blended too quickly in memory. It was time to derail the train, jump off, and walk into the nearest forest. Not that the dreams alone motivated me to set off rowing, but they reflected, amid my work for one bureaucracy and then another, a need and desire to step, as Robert Frost titled one of his poems, "into my own." In a culture of acquisition and enlargement, I felt an impulse to stop, step back, observe, and live by my wits and material minimums.

And so I decided that I would row the circuit I had traced with a finger as a boy, the same orbit that captured the sailing Blackburn, a circumnavigation whose point of departure would evolve into a point of return. For the real meaning of circumnavigation lies not just in movement from Point A to Point A, but in the opportunity to mark change in oneself at two different times in the same place. The beginning becomes the end as we labor, react, create, flourish, or suffer to make it so. In short, to answer the question that was to become so common, nothing possessed me. I possessed myself.

The route would begin in New York City and lead to the Gulf of Mexico, following a series of waterways including the Hudson River, the Erie Canal, and Lake Erie. With a nod to those merchant mariners, including Blackburn, who'd claimed the Great Lakes were as treacherous as any oceans they'd sailed, I would search for the simplest portage from Lake Erie toward the Allegheny or Ohio. The Ohio leads to the Mississippi, and the Mississippi gives way to the Gulf. And, if I made it that far, I would row the Gulf coast to Key West, and the Atlantic coast back to Brooklyn.

In a rented sandstone farmhouse on the Zuni Indian Reservation, where I'd spent the previous few years teaching and running the local newspaper, I saw a magazine advertisement for a rowing shell I thought would be appropriate for the trip, and with a description of the route, sent off a request for a brochure. Soon I received a letter from the company offering the use of one of their boats, a sleek scull with a sliding seat and long oars, for my endeavor. I was ecstatic. As I stood outside my local post office, where tumbleweeds often roll down the main road until they get caught up in some wire fence, and four hundred miles from the nearest body of open water, the trip had suddenly become a reality. I left my job with the newspaper and headed east.

From the Hardcover edition.

A Perceptible Wake

"What street are we at?" I call up to a jogger who's been watching as my strokes against the river's current overtake his strides along the promenade. He glances to his left, where one of the lesser architectural canyons of Manhattan is marked by a street sign just out of my view.

"One-hundred-and-tenth Street," he reports. A moment of silence as we acknowledge each other in self-propulsion.

"How far are you going?"

I search the riverscape briefly, then look back to him: "Bourbon Street!"

A blank look. He carries his momentum through a few more strides while I take a couple of strokes. And then suddenly he smiles and punches a fist up into the air.

It is spring on the Harlem River. As I row northward, people fishing from the granite seawall cast their lures and hooks on silken strands that sing out across the water. The way the weighted barbs arc across the blue April sky you'd think the aim, spiderlike, was for the opposing shore of the Bronx. Then, reels spent, they lose their flight and softly plunge into brown, working water, and the slackened filaments follow, sighing across the river's surface. There are others too, families and friends, who sit on city benches, talking and laughing, or reading, or with their eyes closed and faces tilted up to the spring-warm sun. Some lean against the green metal railing with their forearms, hands clasped, looking down at the river, or beyond the river to the Bronx, or, as I pass by, at me. Young children wave to me through the bars of the railing. One boy is too tall to look below the handrail, but too short to look above. He stretches his legs for the upper view, then stoops for the lower and waves. Some call out to ask where I'm going, and I tell them "New Orleans!" or "the Gulf of Mexico!" One man with a thick city accent corrects me, pointing south: "You're goin' the wrong way, man! New Orleans is that way!" He won't be the last to say so as I proceed up the Hudson toward Albany, and west along the Erie Canal toward Buffalo, five hundred miles of rowing without an inch gained toward the gulf before finally swinging the bow southward toward the land of the Cajuns.

Already the palms of my hands have opened up to the deepest layers of skin. Two months before setting out I started training on a rowing machine in hopes of building my calluses, but the machine doesn't mimic the feathering of the oars, and any toughness I had has been blistered, ruptured, then slowly worn away as if the trip itself has had a word with me: "Now let me show you what I meant by calluses." The chafing is exacerbated by the rubber grips of my secondhand oars. The parallel fine ridges of rubber tread, presumably once soft, have been hardened by exposure to the sun and slowly pare my hands to their epidermal base. Yet just two weeks and 140 miles from here, at Watervliet, near Albany, I will be given a piece of 80-grit sandpaper with which I'll scour smooth the ridges of my leathered palms.

"What possessed you?"

A question I was frequently asked over six thousand miles of rowing. The phrasing rarely wavered, and the verb choice was consistent. It's enough to say that I'm possessed by a love for water and by a fascination with boats. Had I been raised in farm country I might have ridden a horse from Butte to Bar Harbor, but I grew up along the coast of Massachusetts, and the first boat I was ever in by myself was an inflatable dinghy with the wooden oars of a skiff. It was the summer of 1975 and I was seven years old, and I still remember my newfound sense of independence as I struggled to coordinate the two unwieldy oars through the translucent cold below. Two snapshots were taken of me that day. In the first, preserved in the family photo album, I am seated, oars idle in the oarlocks, blades in the water, grinning at the camera and with arms raised in a cheer. In the second picture, with oars not quite synchronized but leaving a perceptible wake, I am rowing away.

Add to my love affair with boats and water a passion for geography. I spent uncounted hours as a child poring through the family atlas, distracted from the center of the universe that was my hometown by the idea that someone, at the same moment, was living in such exotic outbacks as the Zuni Indian Reservation in New Mexico, or along the simple crosshairs of Leola, South Dakota, or at the end of the dead-end road to Candelaria, West Texas. At some point, when I was perhaps ten, while studying the Mississippi River, the Great Lakes, and their outlet down the St. Lawrence to the sea, it occurred to me that the right combination of blue watery veins on the atlas maps might provide a narrow yet unbroken channel between the North Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico. From Lake Erie I traced the dead-end Sandusky, and eyed the Maumee River, which very nearly kisses the Wabash, a tributary of the Ohio. To the east, heading inland from Lake Ontario, the Genesee's shared geological roots with the Allegheny tempted me. I discovered, though, that they too are divided, with headwaters some five miles apart, as one drains toward the Atlantic and the other toward the Gulf of Mexico. Just cousins.

I traced west through the pages of the atlas, past, for my purposes, riverless Michigan and Indiana, and arrived by finger at Chicago. There I discovered I'd been right to mount the quest, for parallel to both the Adlai E. Stevenson Expressway and the partly filled Illinois and Michigan Canal runs the thirty-mile thread of the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal. Though I imagined a gapingly wide sewage gutter plied by oceangoing ships with foreign flags, a canal is a canal, and by Joliet, heading south, it becomes the Illinois River, bound for the Mississippi. Despite this technicality of American engineering, and with Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and a bit of Quebec included, I've thought of the eastern United States as an island ever since.

A final seed of motivation was planted shortly after the day of my college graduation when, as I bade farewell to extended youth, I was diagnosed with chicken pox. While friends celebrated and planned their next steps, I sat at home for three weeks, let my whiskers grow into a beard I was not allowed to scratch, and read. I became immersed in Lone Voyager, Joseph Garland's biography of Howard Blackburn, a late-nineteenth-century Gloucester fisherman. While fishing for halibut in January on Newfoundland's Burgeo Bank, Blackburn and his dory mate, Thomas Welch, were separated from their mother schooner, the Grace L. Fears, by a blizzard. When the blizzard gave way to night and a cloudless gale, the two could see the lantern lights of the schooner on the windward horizon, but they were unable to row their lumbering dory against the waves. By morning they had been blown out of sight of the Grace L. Fears.

The two men took turns bailing for their lives as the gale continued, and in doing so inadvertently bailed from the boat Blackburn's woolen mittens, which he'd tossed into the salty bilge to keep them from freezing solid while he worked. Soon as Welsh weakened in the cold, Howard's fingers grew frostbitten and useless. With rowing for the coast his only hope, he forced his fingers around the handles of the oars. In twenty minutes they were frozen claws.

On the second night, with the gale unabated, Thomas Welch died of exposure. With his frozen partner as company and ballast, Blackburn managed to continue bailing with his lifeless hands. At dawn of the third day the wind eased and he started rowing north toward the coast of Newfoundland, some sixty miles away. For two days and a night Blackburn continued on, his fingers worn bare to the bone on the wooden handles of the oars.

Amazingly, Blackburn reached the desolate coast, and happened to find an abandoned, roofless shack in which he spent a night fighting his lethal desire for sleep. The following day, after attempting to remove Welch's corpse from the boat and losing it to the salty depths, Blackburn set out again in his dory and headed west along the rugged coast in search of help. On the fifth night after Howard Blackburn and Thomas Welch were lost on the wintry sea, Blackburn was rescued when he landed near a settlement of impoverished fishermen, who over the following months nursed him to digitless health.

After returning to fame in Gloucester and a venture as a successful tavern owner, Blackburn grew restless and taught himself to sail despite the limited usefulness of his hands. After several solo transatlantic crossings in smaller and smaller boats, he embarked in 1902 on a circumnavigation of the eastern United States by sail. He cruised his gaff-rigged sloop, Great Republic, up the Hudson River, towed his boat from the footpath the length of the Erie Canal, and then sailed the Great Lakes to Chicago. Eight decades before I had stumbled across it in an atlas, Blackburn traveled the Illinois and Michigan Canal to the Illinois River, and was soon headed down the Mississippi for the Gulf of Mexico.

Upon rounding Florida and reaching Miami, Blackburn had nearly had enough. Among other obstacles, his deep-draft vessel had regularly encountered the shallow depths of Mississippi sandbars and the shoals of the Gulf coast. After running hard aground near Miami, he sold Great Republic and with characteristic obstinacy replaced it with a twelve-foot rowing boat. Blackburn managed, with a leather strap around each wrist, to row another two hundred miles up the coast of Florida, at which point he'd had fully enough, and took a steamer back to New England.

Yet Blackburn had thought of the island too. I was entranced. I pulled out my road atlas, with its detailed representation of American rivers--the book most often by my side--and studied the route and possible alternatives. By the time I had finished Lone Voyager I'd decided that the ideal nonmotorized vessel, for its shallow draft, carrying capacity, and ability to progress in wind or calm, was a rowing boat. And over the following seven years, years spent discouragingly far from navigable water, my bedtime reading was often from the atlas. I wondered how many miles I could row in a day, and for how many days on end.

I had plain adventure in mind, to be sure. I imagined camping along riverbanks, dodging coal barges, and simply being in a boat on the water. But there was more to it than boyhood fantasy, and it's not enough just to add that I wanted the physical challenge. Over a period of several years, in a recurring dream of descent into darkness, I found myself following narrow, wooden, rickety stairs, dimly lit, perhaps by a hanging bulb, to a musty cellar, which in turn led through a trapdoor or some gaping hole to other stairs and other cellars, one below another. In variations of the dream I followed tunnels borrowed from Edgar Allan Poe--ever constricting but not dead-ending--or ventured into darkened water through which I dived headlong, uncertain whether the bottom was feet or fathoms below. Sometimes I carried a light that emitted a murky glow, then died. Other times I had enough light only to say the darkness was not absolute.

The dreams were tense, yet void of fear. I was not running from anything, but was being drawn toward some unknown, in cellars and tunnels and oceans never fully plumbed. To me, they suggested an inner search for something more, perhaps, for something richer, more off-centering than what my everyday, familiar routines allowed. It was true, I'd been treading water, wondering what was next, and waking up in the morning had become more of a habit than an opportunity. Days were becoming forgettable; they blended too quickly in memory. It was time to derail the train, jump off, and walk into the nearest forest. Not that the dreams alone motivated me to set off rowing, but they reflected, amid my work for one bureaucracy and then another, a need and desire to step, as Robert Frost titled one of his poems, "into my own." In a culture of acquisition and enlargement, I felt an impulse to stop, step back, observe, and live by my wits and material minimums.

And so I decided that I would row the circuit I had traced with a finger as a boy, the same orbit that captured the sailing Blackburn, a circumnavigation whose point of departure would evolve into a point of return. For the real meaning of circumnavigation lies not just in movement from Point A to Point A, but in the opportunity to mark change in oneself at two different times in the same place. The beginning becomes the end as we labor, react, create, flourish, or suffer to make it so. In short, to answer the question that was to become so common, nothing possessed me. I possessed myself.

The route would begin in New York City and lead to the Gulf of Mexico, following a series of waterways including the Hudson River, the Erie Canal, and Lake Erie. With a nod to those merchant mariners, including Blackburn, who'd claimed the Great Lakes were as treacherous as any oceans they'd sailed, I would search for the simplest portage from Lake Erie toward the Allegheny or Ohio. The Ohio leads to the Mississippi, and the Mississippi gives way to the Gulf. And, if I made it that far, I would row the Gulf coast to Key West, and the Atlantic coast back to Brooklyn.

In a rented sandstone farmhouse on the Zuni Indian Reservation, where I'd spent the previous few years teaching and running the local newspaper, I saw a magazine advertisement for a rowing shell I thought would be appropriate for the trip, and with a description of the route, sent off a request for a brochure. Soon I received a letter from the company offering the use of one of their boats, a sleek scull with a sliding seat and long oars, for my endeavor. I was ecstatic. As I stood outside my local post office, where tumbleweeds often roll down the main road until they get caught up in some wire fence, and four hundred miles from the nearest body of open water, the trip had suddenly become a reality. I left my job with the newspaper and headed east.

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

Now in paperback: In a new twist on the nautical voyage, author Stone rows his way around the "eastern island" of the United States in a 17-foot scull offering a unique tour of America and a pioneering personal story perfect for boat-lovers everywhere.