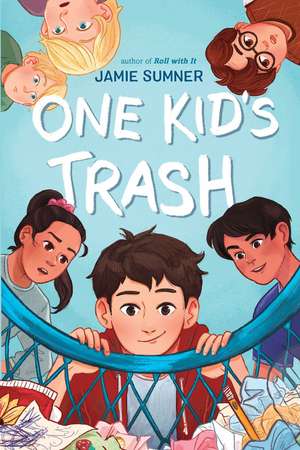

One Kid's Trash

Autor Jamie Sumneren Limba Engleză Paperback – 8 dec 2022 – vârsta de la 10 ani

Hugo is not happy about being dragged halfway across the state of Colorado just because his dad had a midlife crisis and decided to become a ski instructor. It’d be different if Hugo weren’t so tiny, if girls didn’t think he was adorable like a puppy in a purse and guys didn’t call him “leprechaun” and rub his head for luck. But here he is, the tiny new kid on his first day of middle school.

When his fellow students discover his remarkable talent for garbology, the science of studying trash to tell you anything you could ever want to know about a person, Hugo becomes the cool kid for the first time in his life. But what happens when it all goes to his head?

Preț: 45.50 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 68

Preț estimativ în valută:

8.71€ • 9.31$ • 7.26£

8.71€ • 9.31$ • 7.26£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 28 martie-09 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781534457041

ISBN-10: 1534457046

Pagini: 256

Ilustrații: f-c cvr (spfx: spot gloss on matte); digital

Dimensiuni: 130 x 194 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Atheneum Books for Young Readers

Colecția Atheneum Books for Young Readers

ISBN-10: 1534457046

Pagini: 256

Ilustrații: f-c cvr (spfx: spot gloss on matte); digital

Dimensiuni: 130 x 194 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Atheneum Books for Young Readers

Colecția Atheneum Books for Young Readers

Notă biografică

Jamie Sumner is the author of Roll with It, Time to Roll, Rolling On, Tune It Out, One Kid’s Trash, The Summer of June, Maid for It, Deep Water, Please Pay Attention, and Schooled. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and other publications. She loves stories that celebrate the grit and beauty in all kids. She is also the mother of a son with cerebral palsy and has written extensively about parenting a child with special needs. She and her family live in Nashville, Tennessee. Visit her at Jamie-Sumner.com.

Extras

Chapter One: The Coefficient of Hugo

![]()

Chapter One The Coefficient of Hugo

The beautiful and terrible thing about having your bedroom in the basement is that you never know what time it is. So when Mom yells down the stairs, “Hugo, if you don’t get up this minute, you will miss the bus!” I assume that I am already late. And if I miss the bus, there is only one other option: Mom drives me. Which isn’t really an option at all. I am not having my mother drive me to the first day of middle school. That’s social suicide. A guy like me can’t afford to take chances.

I sprint to the bathroom and take the fastest shower in the history of showers. And then I run up the stairs with socks in my mouth and my arms full of jacket, shoes, and backpack. Mom takes one look at me in the hallway and says, “You can’t go out with your hair wet.”

I spit the socks onto the floor.

“Either I catch the bus, or I dry my hair. You can’t have it both ways, Mom.”

I start yanking on a sock, slightly damp from my mouth. Mom watches in her pink fuzzy bathrobe. Back home she was the first one up and dressed and out the door. She had her own private therapy practice in an office building downtown. Client appointments started at eight a.m., which I never understood. If I could set my own schedule, nothing would begin before eleven.

She crouches down and hands me my other sock. Then she reaches out like she’s going to fix my hair. It’s shooting in a million different directions. I bob and weave like a boxer.

“Mom. No.”

“Okay, I just— Do you have your phone?”

The phone is new. They said I couldn’t have one until I turned twelve, which isn’t until April, but I guess with the move they thought I’d need it sooner. So uprooting my entire life came with one bonus.

“Yeah, I got it.” I stand and grab my bag.

“Here, take this.” She tosses me a chocolate PediaSure.

“No. Uh-uh.” I throw it back to her like a hot potato. “I’m too old for this.”

“You’re only too old when Dr. Ross says you’re too old.” She stuffs the bottle in my bag.

Dr. Ross is my pediatrician. She’s had me on a weight-gain plan since, well, when I came out of the womb two months too soon. I bet I’ve drunk approximately four thousand shakes. “Creamy” chocolate, “French” vanilla, “very berry” strawberry—they all taste like chalk. And they don’t work… obviously. I’m the dot on the growth chart that can’t reach a line. I’m Ant-Man if he couldn’t unshrink himself. My aunt once bought me age-appropriate athletic shorts for my birthday. They came to my shins. Adam, the meanest kid in second grade, took one look at me and said, “Nice pants, Shorts.” That was my name for the next two years. Please, please, please, I say to the universe as I head out the door, don’t let me be Shorts again. The universe probably isn’t listening. I bet it doesn’t take client calls until eleven.

“Text if you need anything, okay?” Mom says. I sigh but give her a side hug as Dad comes skidding down the hall at a run.

He’s in jeans and he’s fighting the zipper on his Patagonia jacket. The zipper seems to be winning. It’s weird to see him without a tie. “Come on, I’ll walk you to—” He checks his watch. “Er, we’ll jog to the bus stop.” That’s the other new thing. We sold Mom’s Tahoe to help save money while she builds up her practice again and Dad does… whatever Dad plans to do. Now he has to catch the bus, just like me. Except his bus carries him to his new job in Creekside, the resort town at the top of the mountain, and mine takes me to purgatory—I mean, middle school.

I follow him out the door. His hair may be a totally different color, carroty red compared to my dark brown, but it looks just as bad as mine—permanent bedhead. Outside, the wind is fierce and yellow birch leaves dart through the air like angry hummingbirds. It’s only the beginning of September, but you can smell the cold coming.

We jog toward the end of the block and then break into a sprint when the bus passes us on its way to the corner. It screeches to a halt in a cloud of exhaust—the little engine that couldn’t—and I barely make it before it chugs off again. This is good. I’m so late I don’t have time to be nervous. I hurl myself into the heat of the bus before the doors whoosh closed behind me. I dart up the steps as fast as I can, praying for invisibility. But when I turn down the aisle, the bus driver says, “Hey, little fella, there’s plenty of room up front.” She points to the empty seat right behind her. Little fella. Two girls across the aisle giggle. I don’t even dare to look at anybody else. I walk all the way to an unoccupied row near the back. Outside on the sidewalk, Dad waves and waves and waves. I ignore him and blink back the tears that could only make this situation worse.

And so it begins.

Beech Creek Middle School looks a lot like every other public school in the universe. When we pull into the circle, I take my time filing out and give the place a nervous once-over. It’s a brick, one-story building, one long Lego, except it has stone columns in front of the main entrance—an attempt to be as classy as the resort up the hill. But it’s just a game of dress-up. If you live down here, you’re not a part of that world. Anybody rich enough to actually live in a lodge/chalet/palace up on high goes to the private school outside Vail.

How do I know this, as the new kid? My cousin Vijay, Vij, also lives here and goes to Beech Creek. He gave me the lowdown on the who, what, when, and where of the place. He was trying to help, but every conversation ended with me hanging up the phone and gently banging my head against the window of the bedroom in Denver that I did not want to leave. Trying to fit into a new school is like studying for a test for a class you’ve never taken.

It took me until fourth grade to make any friends worth keeping—Jason and Marquis and Cole, who are probably already searching for my FIFA replacement. Marquis was the first one to show me how to double tap the shoot button at the right time. I scored some sublime goals because of him. He’s also the first one who invited me over for game night and introduced me to Jason and Cole and their intense love for spray cheese. I will not miss the cheese, but I will miss them.

I hitch my backpack up on my shoulders. Vij waits for me by the main entrance. He’s wearing sunglasses even though the sky is one long blanket of cloud, and he’s throwing a bouncy ball over and over against one of the stone columns. He looks like he’s been here his whole life. I wish I had that level of confidence about anything.

“Hey,” I say, and duck as the bouncy ball goes careening off the stone, over my head, and into the street.

Vij lets it go.

“Hey, dude. You ready?” He lifts his glasses and his eyebrows at the same time. I’m not ready. Of course I’m not, but what am I going to do, hide under the cars with the bouncy ball? I take a deep breath and let him lead me inside.

I do not make eye contact with a single person. My stomach sloshes with Cinnamon Toast Crunch and nerves. Vij high-fives everyone, including the secretary, who hands me my schedule and ruffles my hair on my way to first period. I blush and keep my eyes trained on the ground. Females find my smallness irresistible, but in the worst way possible. I am a potential pet.

I have English first with Vij, who directs us both to the back corner near the window. Because this is the first day of middle school for the entire sixth grade, I assumed everyone else would be stunned into submission, like me, by the boatload of newness. But they all already know one another because they went to elementary school together. It’s like trying to join a team when the positions are already filled. I wait, slightly behind Vij, while he does the whole “hey, this is my cuz, be nice to him” thing. I love my cousin. But I wish I didn’t need a tour guide for my own life. I smile shyly at the floor and ignore the girls who whisper “isn’t he cute” because I know they don’t mean “cool.” They mean “adorable,” like a puppy they want to carry around. No guy wants to be adorable. Ever.

Vij takes the last seat in the row, leaving the one right in front of him open for me. I sit and do what I’ve been doing since first grade: slouch down in my seat so you can’t tell exactly how short I really am. I wouldn’t have been the king of the school by a long shot, but at least if I’d stayed in Denver I would have still had my friends, the ones who let me have the lowest swing on the playground without making a big deal about it and came over to play Xbox all summer and basically forgot I was little Hugo and just thought of me as Hugo. I watch everyone else out of the corner of my eye. They already know who to sit with and what color one another’s walls are at home and what movies they saw this summer. Like the new Marvel movie me and Jason and Marquis and Cole saw in the dine-in theater before I left. We ate nachos and drank slushies and laughed at all the bad superhero lines.

During roll call, I nudge Vij when they call his name, because he’s already not listening. He stares out the window, totally engrossed in the plight of a Doritos bag blowing across the parking lot. Our English teacher, Mrs. Jacobsen, says his name sharply, like fingers snapping, over and over until he mumbles “here.” She wears square red glasses that she pushes up on her head and then can’t find when they get lost in her curly hair during her PowerPoint. She seems all right, but kind of scary in that “I can do the crossword puzzle in eight seconds” way. Her syllabus is twelve pages long, front and back. I didn’t even know what a syllabus was until today. Lucky for me, she included the definition on page one.

Vij and I split up for second period. I talk to no one, look at no one, and say exactly two words: “yes, ma’am” when my Spanish teacher, Señora Molitoris, asks me if I’m settling in okay. I’m so relieved to see Vij when we meet again for third period that I have to stop myself from hugging him. Then the bell rings and Mr. Wahl, our algebra teacher, slams the door like he’s locking in the prisoners. A gloom settles over the room that has nothing to do with the clouds outside. I shiver.

There’s always one class where the goal is simply to survive. You’re not aiming for As or Bs or to make a new best friend. You just want to get through. As the seconds tick by and Mr. Wahl stares at the class, saying nothing, not even blinking, I realize this is my survival class. My throat fills with cotton. I couldn’t swallow even if I wanted to, which I don’t, because I am already terrified of drawing his laser eyes toward me.

The first, and nicest thing, I can say about Mr. Wahl is that at least he’s color coordinated. Which is to say, he wears entirely one hue: tan. Tan shirt tucked into tan pants that are just short enough to reveal tan socks. His hair is the same washed-out brown as his shoes. The only spark of color on him is a green notepad sticking out of his shirt pocket. It is a packet of detention slips.

He doesn’t call roll. Instead, he passes a sheet of paper down the aisle, and we’re supposed to check ourselves off a list. I’m pretty sure he isn’t planning on talking at all, or you know, trying to match actual faces with names. Vij, who is sitting behind me again, decides this is excellent.

“Man, you think he even counts heads?” he whispers. “I could put a mop in this seat, and he wouldn’t notice.” He looks out the window again. I follow his gaze. He’s staring at the road that leads up the mountain. It’s lined with flags of all the countries of the world. It’s Creekside’s royal welcome to ski country.

“Uh-uh. No way.” I shake my head.

“What?” he says in the voice he uses when his mom asks if he’s the reason his little sister is crying.

“There’s not even snow yet, Vijay. We can’t skip school to go skiing. Our parents will murder us and then host a double funeral-slash-family reunion.”

“We’re not skipping school, man. I swear.” He scowls at me like I’m the buzzkill of the century. “And don’t call me ‘Vijay.’ You sound like my mother.”

“You. Back right.” Mr. Wahl’s voice lashes out from the front of the room like a whip. “What’s your name?”

“O’Connell, sir,” Vij says, the “sir” sounding more like a curse.

“And you.” He points at me. “Name.”

“O’Connell.”

He walks halfway up our aisle. Behind all that tan, he’s younger than he looks. I shrink down farther in my seat.

“Is this a joke?”

“No, sir,” I say now, because Vij is ignoring us both and studying his hands like they hold the mystery of the universe. “We’re cousins.”

Mr. Wahl looks back and forth between us. I can see him comparing Vij’s brown skin and my pasty white face and weighing the odds. Then he shakes his head and stalks back to the front of the room.

“Mr. Vijay O’Connell, what’s the coefficient of 10x – 8?”

“The ten,” Vij says without looking up. He’s pulled out a Sharpie and is tracing the lines on his palm like a spiderweb. Mr. Wahl blinks. Because Vij never acts like he cares about school, nobody expects him to know anything. But he’s supersmart and he doesn’t even have to try. Same with making friends. He’s always been able to just do things. It’s never bothered me before. In fact, I was proud of him. But it’s different hearing about it on Christmas vacations and summer visits over a campfire. Up close and personal, it’s… annoying. Now that we’re in the same school and wading in the same small pond of people, I kind of wish Vij were a slightly smaller, slightly dumber version of himself. Then I feel bad for thinking that because he’s using all his social superpowers to smooth the way for me. I should be totally grateful to have him here. As Mom loves to say when I refuse to brush my hair, you only get one chance to make a first impression, and Vij is the best chance I’ve got to get it right.

In the cafeteria, I clutch my sack lunch and follow him past the guys in athletic wear—the snowboard, basketball, track crowd, which I assumed (and dreaded) were Vij’s people. Instead, we walk to a table near the windows with just four people. There is not a single Smith or Under Armour logo in sight. Vij points at two guys, both with white-blond hair and freckles, so identical that they have to be twins, and says, “Jackson, Grayson, meet my cousin, Hugo.”

“Jack,” Jackson says.

“Gray,” Grayson says.

I wave. I will never be able to tell them apart.

The kid at my elbow chirps, “I’m Micah!” He has brown hair and glasses with an actual strap across the back. He blinks at me with eyes magnified to unnatural proportions. I recognize him from algebra class. I’m ashamed to admit I singled him out immediately as a potential weaker link than me. While I am shorter than almost any eleven-year-old on the planet, there’s something about Micah that just feels small.

“Do you want my milk? The lunch lady gave me two!” he asks, each sentence ending higher than it started.

I smile and shake my head. “No, thanks.” I would bet a thousand bucks he still sleeps in matching pajamas and uses a light-up toothbrush to tell him how long before he can spit. But at least he doesn’t make me nervous. In fact, this is the first time today that my heart has decided to beat at a normal pace. I might even be able to eat my lunch.

I sneak a look at the end of the table to the girl who has not lifted her head—the only one I haven’t met.

Vij sits down opposite the twins and pulls me down with him. “That,” he says, “is Em.”

“Emilia,” she corrects him while typing on her phone at approximately 1,783 words per minute.

“So you’re the new kid from Denver,” Jack says. Or Gray.

I nod and unwrap my peanut butter and banana sandwich only to discover that my mom has cut it in the shape of a heart. I tear it to pieces as fast as I can, but not before Vij sees.

“Shut up,” I say before he can laugh.

He unsnaps the lid on his own lunch with a flourish. Micah leans over me to see. It’s orange and looks like cat vomit. I make a grab for it.

“Get your hands off.”

“Is that your mom’s curry?” I ask.

Aunt Soniah makes the best curry on the planet. This is a fact. She should get a medal for it. Maybe she has. I wouldn’t be surprised. It is creamy and gingery and just the right amount of spicy. I have dreams about this curry.

While we all watch, Vij unbends the metal spoon attached to the lid like a pocketknife and takes a huge bite. This is what makes Vij impressive. Most kids would be embarrassed to have a lunch that smelled of anything other than pizza or Doritos. But Vij doesn’t care. Careless. Carefree. Envy knits a stitch in my side.

I stare down at my lunch like it’s toilet paper I trailed in on my shoes—a heart torn to pieces and a note from Mom that says “Good luck on your first day! Remember, deep breaths!” It’s humiliating. What sixth grader still gets notes in his lunch? I should throw it away, but I stuff it in my pocket instead. I like knowing it’s there. You would have to make me eat a hundred heart-shaped sandwiches before I’d admit it, though.

Micah shoves his lunch tray under my nose. “You can have some of my spaghetti. I have breadsticks!”

After I politely decline, Vij waves his hand over the table like the host on Jeopardy! and says, “This, my cuz, is the newspaper staff.” He shoots a finger at me. “You, too, could be a part of the dream team.”

“The, uh, what?”

“Did no one tell you?” Vij pretends to be shocked. “News flash: This crew is going to be responsible for the very first newspaper in Beech Creek history.”

Micah gnaws on a breadstick. The twins trade chips. Emilia types. This has to be Vij’s mom’s idea. She’s always penciling in extracurriculars for his future resume. It’s not easy having two older sisters in Ivy League schools and a younger one who reads the dictionary for fun. An afternoon at Vij’s house makes me glad I’m an only child.

Vij bumps my shoulder with his. “You ready to make history, man?”

“Ummm.” It’s not like I had dreams of being cool. Mom always talks about the importance of setting “attainable goals.” Coolness is not an attainable goal for me. And I’ve come to terms with it. But this is the opposite of that. Joining the newspaper staff would be like pinning a bullseye on my back and then passing out flyers advertising free target practice. Suddenly, I am much less comfortable at this table.

“Here it is!” Emilia yells, holding up her phone and rescuing me from Vij’s stare. I could hug her, except she looks like the kind that can and will throw a punch.

“Let me see,” Jack or Gray says.

Emilia passes over her phone. The twins say “uhhh?” together at the exact same time. “Give it, Jack,” Vij says, and takes it from the twin with the scar over his eyebrow. I make a mental note.

“Ummm, no offense, Em, but what am I looking at here?” he asks.

Emilia comes around the table to stand behind us.

“That’s a picture of the parking lot!” she informs us.

“Well, yes. And?” Emilia grabs the phone from him and swipes left, hard.

“And… this is the same red Volvo in the handicapped spot without proper licensure,” she adds, holding it up an inch from his face.

She watches us and waits. For what, I have no idea. When we just sit there, she yanks her ponytail tighter and sighs like my mom.

“That’s illegal,” she explains.

I know it’s a huge mistake before it happens, but everyone knows you can’t stop an eye roll midroll. When she catches me, her glare could melt bones.

“What a lovely addition to our table,” she quips. “Thanks a lot, Vij.”

So, if we’re rating things on a first-day scale, similar to the pain scale at the doctor’s office, one being “I am now king of the school” and ten being “I have to change my name and relocate ASAP,” English and Spanish were solid fours—not terrible, mostly tolerable. Algebra is teetering on a seven with the specter of Mr. Wahl looming for the next nine months. Lunch would have been a three (I ate with other humans who did not try to see if I fit in the trash can), except for the newspaper invite, which will get me thrown in a trash can, so I’m sitting at a solid seven. Emilia would probably say eleven.

But none of that matters, because I am about to enter the most painful part of all: physical education. Gym is the foundation on which the house of bullying was built. Hey kid, you’re about eye-level with everyone else’s elbow, right? Let’s shoot some hoops. Your legs are half the size of everyone else’s? Go line up. It’s relay races. Tug-of-war? We’ll put you in the middle where you can dangle like dead weight. Not even enough dead weight to count.

The locker room reeks of sweat and farts and floor varnish. I find my name along the row. Vij’s locker is on the other side of the room, so I’m standing by myself, trying to shove my sweatshirt on top of my jeans and close the door before everything falls out again, when a hand snakes out and slams it shut. I yank my fingers away just in time.

“Need a little help there, bro?”

A giant has found its way into the locker room.

A huge kid with the beginnings of facial hair smirks at me. His breath smells of pizza and Dr Pepper. I recognize him from math class. His name is Chance Sullivan, and he’s on the basketball team. How could you name your kid “Chance” and ever expect him to be taken seriously?

He looms, serious enough. I start to swallow convulsively. There’s not enough air in the room or spit in my mouth.

“How’d a third grader get in here?” he asks the room at large, and laughs. It is the noise of a frog burping. It’s as dumb an insult as it sounds, and I have heard so much worse. Huge-O. Tiny Tot. Lowrider. Smurfette. Bite-Size. Runt. Hobbit. Oompa Loompa. Arm Rest was the worst because it invited physical contact. As bullies go, Chance is an amateur. For a second his words just hang there, and I pray it’ll come to nothing. Then one kid who’s sitting on the bench and tying his shoes chuckles. That’s all it takes, one laugh, to make it legit. I want to crawl into my locker and hide under my sweatshirt.

“Whatever,” I mumble.

“What’s that?” Chance leans down and I shrink back, which is a mistake. Never retreat.

“Don’t worry about it, bud.” Chance pats me not-so-kindly on the shoulder. “You still got a few years for that voice to drop.” His own voice is the rumble of a motor, a pack-a-day man, a superhero. I will not cry. I just hope I don’t run. In the general allotment of “fight or flight,” I only got flight.

Vij comes to my rescue. I am both thankful and irritated.

“Let’s go,” he says without looking at Chance.

“Vijay, my man. I was just introducing myself to your cousin.” Chance is jolly now, like we’re old pals. Of course he knows we’re cousins. It’s a small school. Everybody probably already knows my pants size too. Vij and I say nothing. Chance turns to go. I think it’s over. Then he reaches out his sweaty hand and rubs my head. “For luck,” he says. “Leprechauns are lucky, right?” So original. Call the tiny Irish kid a leprechaun.

I imagine myself saying something, fighting back: Better a leprechaun than a troll or At least I remembered deodorant. It could be the beginning of a new era. Hugo O’Connell saves himself and saves the day. No more “small” talk. I’d be funny and popular and living my best life. Finally one of the cool kids. But in the end, I just stand there, humiliation fizzing in my chest while everyone else files out. Vij puts his hand on my shoulder. I shake it off.

“Don’t worry about it,” he says when we’re alone. “It’s just ’cause you’re new.”

But we both know that’s a lie.

Chapter One The Coefficient of Hugo

The beautiful and terrible thing about having your bedroom in the basement is that you never know what time it is. So when Mom yells down the stairs, “Hugo, if you don’t get up this minute, you will miss the bus!” I assume that I am already late. And if I miss the bus, there is only one other option: Mom drives me. Which isn’t really an option at all. I am not having my mother drive me to the first day of middle school. That’s social suicide. A guy like me can’t afford to take chances.

I sprint to the bathroom and take the fastest shower in the history of showers. And then I run up the stairs with socks in my mouth and my arms full of jacket, shoes, and backpack. Mom takes one look at me in the hallway and says, “You can’t go out with your hair wet.”

I spit the socks onto the floor.

“Either I catch the bus, or I dry my hair. You can’t have it both ways, Mom.”

I start yanking on a sock, slightly damp from my mouth. Mom watches in her pink fuzzy bathrobe. Back home she was the first one up and dressed and out the door. She had her own private therapy practice in an office building downtown. Client appointments started at eight a.m., which I never understood. If I could set my own schedule, nothing would begin before eleven.

She crouches down and hands me my other sock. Then she reaches out like she’s going to fix my hair. It’s shooting in a million different directions. I bob and weave like a boxer.

“Mom. No.”

“Okay, I just— Do you have your phone?”

The phone is new. They said I couldn’t have one until I turned twelve, which isn’t until April, but I guess with the move they thought I’d need it sooner. So uprooting my entire life came with one bonus.

“Yeah, I got it.” I stand and grab my bag.

“Here, take this.” She tosses me a chocolate PediaSure.

“No. Uh-uh.” I throw it back to her like a hot potato. “I’m too old for this.”

“You’re only too old when Dr. Ross says you’re too old.” She stuffs the bottle in my bag.

Dr. Ross is my pediatrician. She’s had me on a weight-gain plan since, well, when I came out of the womb two months too soon. I bet I’ve drunk approximately four thousand shakes. “Creamy” chocolate, “French” vanilla, “very berry” strawberry—they all taste like chalk. And they don’t work… obviously. I’m the dot on the growth chart that can’t reach a line. I’m Ant-Man if he couldn’t unshrink himself. My aunt once bought me age-appropriate athletic shorts for my birthday. They came to my shins. Adam, the meanest kid in second grade, took one look at me and said, “Nice pants, Shorts.” That was my name for the next two years. Please, please, please, I say to the universe as I head out the door, don’t let me be Shorts again. The universe probably isn’t listening. I bet it doesn’t take client calls until eleven.

“Text if you need anything, okay?” Mom says. I sigh but give her a side hug as Dad comes skidding down the hall at a run.

He’s in jeans and he’s fighting the zipper on his Patagonia jacket. The zipper seems to be winning. It’s weird to see him without a tie. “Come on, I’ll walk you to—” He checks his watch. “Er, we’ll jog to the bus stop.” That’s the other new thing. We sold Mom’s Tahoe to help save money while she builds up her practice again and Dad does… whatever Dad plans to do. Now he has to catch the bus, just like me. Except his bus carries him to his new job in Creekside, the resort town at the top of the mountain, and mine takes me to purgatory—I mean, middle school.

I follow him out the door. His hair may be a totally different color, carroty red compared to my dark brown, but it looks just as bad as mine—permanent bedhead. Outside, the wind is fierce and yellow birch leaves dart through the air like angry hummingbirds. It’s only the beginning of September, but you can smell the cold coming.

We jog toward the end of the block and then break into a sprint when the bus passes us on its way to the corner. It screeches to a halt in a cloud of exhaust—the little engine that couldn’t—and I barely make it before it chugs off again. This is good. I’m so late I don’t have time to be nervous. I hurl myself into the heat of the bus before the doors whoosh closed behind me. I dart up the steps as fast as I can, praying for invisibility. But when I turn down the aisle, the bus driver says, “Hey, little fella, there’s plenty of room up front.” She points to the empty seat right behind her. Little fella. Two girls across the aisle giggle. I don’t even dare to look at anybody else. I walk all the way to an unoccupied row near the back. Outside on the sidewalk, Dad waves and waves and waves. I ignore him and blink back the tears that could only make this situation worse.

And so it begins.

Beech Creek Middle School looks a lot like every other public school in the universe. When we pull into the circle, I take my time filing out and give the place a nervous once-over. It’s a brick, one-story building, one long Lego, except it has stone columns in front of the main entrance—an attempt to be as classy as the resort up the hill. But it’s just a game of dress-up. If you live down here, you’re not a part of that world. Anybody rich enough to actually live in a lodge/chalet/palace up on high goes to the private school outside Vail.

How do I know this, as the new kid? My cousin Vijay, Vij, also lives here and goes to Beech Creek. He gave me the lowdown on the who, what, when, and where of the place. He was trying to help, but every conversation ended with me hanging up the phone and gently banging my head against the window of the bedroom in Denver that I did not want to leave. Trying to fit into a new school is like studying for a test for a class you’ve never taken.

It took me until fourth grade to make any friends worth keeping—Jason and Marquis and Cole, who are probably already searching for my FIFA replacement. Marquis was the first one to show me how to double tap the shoot button at the right time. I scored some sublime goals because of him. He’s also the first one who invited me over for game night and introduced me to Jason and Cole and their intense love for spray cheese. I will not miss the cheese, but I will miss them.

I hitch my backpack up on my shoulders. Vij waits for me by the main entrance. He’s wearing sunglasses even though the sky is one long blanket of cloud, and he’s throwing a bouncy ball over and over against one of the stone columns. He looks like he’s been here his whole life. I wish I had that level of confidence about anything.

“Hey,” I say, and duck as the bouncy ball goes careening off the stone, over my head, and into the street.

Vij lets it go.

“Hey, dude. You ready?” He lifts his glasses and his eyebrows at the same time. I’m not ready. Of course I’m not, but what am I going to do, hide under the cars with the bouncy ball? I take a deep breath and let him lead me inside.

I do not make eye contact with a single person. My stomach sloshes with Cinnamon Toast Crunch and nerves. Vij high-fives everyone, including the secretary, who hands me my schedule and ruffles my hair on my way to first period. I blush and keep my eyes trained on the ground. Females find my smallness irresistible, but in the worst way possible. I am a potential pet.

I have English first with Vij, who directs us both to the back corner near the window. Because this is the first day of middle school for the entire sixth grade, I assumed everyone else would be stunned into submission, like me, by the boatload of newness. But they all already know one another because they went to elementary school together. It’s like trying to join a team when the positions are already filled. I wait, slightly behind Vij, while he does the whole “hey, this is my cuz, be nice to him” thing. I love my cousin. But I wish I didn’t need a tour guide for my own life. I smile shyly at the floor and ignore the girls who whisper “isn’t he cute” because I know they don’t mean “cool.” They mean “adorable,” like a puppy they want to carry around. No guy wants to be adorable. Ever.

Vij takes the last seat in the row, leaving the one right in front of him open for me. I sit and do what I’ve been doing since first grade: slouch down in my seat so you can’t tell exactly how short I really am. I wouldn’t have been the king of the school by a long shot, but at least if I’d stayed in Denver I would have still had my friends, the ones who let me have the lowest swing on the playground without making a big deal about it and came over to play Xbox all summer and basically forgot I was little Hugo and just thought of me as Hugo. I watch everyone else out of the corner of my eye. They already know who to sit with and what color one another’s walls are at home and what movies they saw this summer. Like the new Marvel movie me and Jason and Marquis and Cole saw in the dine-in theater before I left. We ate nachos and drank slushies and laughed at all the bad superhero lines.

During roll call, I nudge Vij when they call his name, because he’s already not listening. He stares out the window, totally engrossed in the plight of a Doritos bag blowing across the parking lot. Our English teacher, Mrs. Jacobsen, says his name sharply, like fingers snapping, over and over until he mumbles “here.” She wears square red glasses that she pushes up on her head and then can’t find when they get lost in her curly hair during her PowerPoint. She seems all right, but kind of scary in that “I can do the crossword puzzle in eight seconds” way. Her syllabus is twelve pages long, front and back. I didn’t even know what a syllabus was until today. Lucky for me, she included the definition on page one.

Vij and I split up for second period. I talk to no one, look at no one, and say exactly two words: “yes, ma’am” when my Spanish teacher, Señora Molitoris, asks me if I’m settling in okay. I’m so relieved to see Vij when we meet again for third period that I have to stop myself from hugging him. Then the bell rings and Mr. Wahl, our algebra teacher, slams the door like he’s locking in the prisoners. A gloom settles over the room that has nothing to do with the clouds outside. I shiver.

There’s always one class where the goal is simply to survive. You’re not aiming for As or Bs or to make a new best friend. You just want to get through. As the seconds tick by and Mr. Wahl stares at the class, saying nothing, not even blinking, I realize this is my survival class. My throat fills with cotton. I couldn’t swallow even if I wanted to, which I don’t, because I am already terrified of drawing his laser eyes toward me.

The first, and nicest thing, I can say about Mr. Wahl is that at least he’s color coordinated. Which is to say, he wears entirely one hue: tan. Tan shirt tucked into tan pants that are just short enough to reveal tan socks. His hair is the same washed-out brown as his shoes. The only spark of color on him is a green notepad sticking out of his shirt pocket. It is a packet of detention slips.

He doesn’t call roll. Instead, he passes a sheet of paper down the aisle, and we’re supposed to check ourselves off a list. I’m pretty sure he isn’t planning on talking at all, or you know, trying to match actual faces with names. Vij, who is sitting behind me again, decides this is excellent.

“Man, you think he even counts heads?” he whispers. “I could put a mop in this seat, and he wouldn’t notice.” He looks out the window again. I follow his gaze. He’s staring at the road that leads up the mountain. It’s lined with flags of all the countries of the world. It’s Creekside’s royal welcome to ski country.

“Uh-uh. No way.” I shake my head.

“What?” he says in the voice he uses when his mom asks if he’s the reason his little sister is crying.

“There’s not even snow yet, Vijay. We can’t skip school to go skiing. Our parents will murder us and then host a double funeral-slash-family reunion.”

“We’re not skipping school, man. I swear.” He scowls at me like I’m the buzzkill of the century. “And don’t call me ‘Vijay.’ You sound like my mother.”

“You. Back right.” Mr. Wahl’s voice lashes out from the front of the room like a whip. “What’s your name?”

“O’Connell, sir,” Vij says, the “sir” sounding more like a curse.

“And you.” He points at me. “Name.”

“O’Connell.”

He walks halfway up our aisle. Behind all that tan, he’s younger than he looks. I shrink down farther in my seat.

“Is this a joke?”

“No, sir,” I say now, because Vij is ignoring us both and studying his hands like they hold the mystery of the universe. “We’re cousins.”

Mr. Wahl looks back and forth between us. I can see him comparing Vij’s brown skin and my pasty white face and weighing the odds. Then he shakes his head and stalks back to the front of the room.

“Mr. Vijay O’Connell, what’s the coefficient of 10x – 8?”

“The ten,” Vij says without looking up. He’s pulled out a Sharpie and is tracing the lines on his palm like a spiderweb. Mr. Wahl blinks. Because Vij never acts like he cares about school, nobody expects him to know anything. But he’s supersmart and he doesn’t even have to try. Same with making friends. He’s always been able to just do things. It’s never bothered me before. In fact, I was proud of him. But it’s different hearing about it on Christmas vacations and summer visits over a campfire. Up close and personal, it’s… annoying. Now that we’re in the same school and wading in the same small pond of people, I kind of wish Vij were a slightly smaller, slightly dumber version of himself. Then I feel bad for thinking that because he’s using all his social superpowers to smooth the way for me. I should be totally grateful to have him here. As Mom loves to say when I refuse to brush my hair, you only get one chance to make a first impression, and Vij is the best chance I’ve got to get it right.

In the cafeteria, I clutch my sack lunch and follow him past the guys in athletic wear—the snowboard, basketball, track crowd, which I assumed (and dreaded) were Vij’s people. Instead, we walk to a table near the windows with just four people. There is not a single Smith or Under Armour logo in sight. Vij points at two guys, both with white-blond hair and freckles, so identical that they have to be twins, and says, “Jackson, Grayson, meet my cousin, Hugo.”

“Jack,” Jackson says.

“Gray,” Grayson says.

I wave. I will never be able to tell them apart.

The kid at my elbow chirps, “I’m Micah!” He has brown hair and glasses with an actual strap across the back. He blinks at me with eyes magnified to unnatural proportions. I recognize him from algebra class. I’m ashamed to admit I singled him out immediately as a potential weaker link than me. While I am shorter than almost any eleven-year-old on the planet, there’s something about Micah that just feels small.

“Do you want my milk? The lunch lady gave me two!” he asks, each sentence ending higher than it started.

I smile and shake my head. “No, thanks.” I would bet a thousand bucks he still sleeps in matching pajamas and uses a light-up toothbrush to tell him how long before he can spit. But at least he doesn’t make me nervous. In fact, this is the first time today that my heart has decided to beat at a normal pace. I might even be able to eat my lunch.

I sneak a look at the end of the table to the girl who has not lifted her head—the only one I haven’t met.

Vij sits down opposite the twins and pulls me down with him. “That,” he says, “is Em.”

“Emilia,” she corrects him while typing on her phone at approximately 1,783 words per minute.

“So you’re the new kid from Denver,” Jack says. Or Gray.

I nod and unwrap my peanut butter and banana sandwich only to discover that my mom has cut it in the shape of a heart. I tear it to pieces as fast as I can, but not before Vij sees.

“Shut up,” I say before he can laugh.

He unsnaps the lid on his own lunch with a flourish. Micah leans over me to see. It’s orange and looks like cat vomit. I make a grab for it.

“Get your hands off.”

“Is that your mom’s curry?” I ask.

Aunt Soniah makes the best curry on the planet. This is a fact. She should get a medal for it. Maybe she has. I wouldn’t be surprised. It is creamy and gingery and just the right amount of spicy. I have dreams about this curry.

While we all watch, Vij unbends the metal spoon attached to the lid like a pocketknife and takes a huge bite. This is what makes Vij impressive. Most kids would be embarrassed to have a lunch that smelled of anything other than pizza or Doritos. But Vij doesn’t care. Careless. Carefree. Envy knits a stitch in my side.

I stare down at my lunch like it’s toilet paper I trailed in on my shoes—a heart torn to pieces and a note from Mom that says “Good luck on your first day! Remember, deep breaths!” It’s humiliating. What sixth grader still gets notes in his lunch? I should throw it away, but I stuff it in my pocket instead. I like knowing it’s there. You would have to make me eat a hundred heart-shaped sandwiches before I’d admit it, though.

Micah shoves his lunch tray under my nose. “You can have some of my spaghetti. I have breadsticks!”

After I politely decline, Vij waves his hand over the table like the host on Jeopardy! and says, “This, my cuz, is the newspaper staff.” He shoots a finger at me. “You, too, could be a part of the dream team.”

“The, uh, what?”

“Did no one tell you?” Vij pretends to be shocked. “News flash: This crew is going to be responsible for the very first newspaper in Beech Creek history.”

Micah gnaws on a breadstick. The twins trade chips. Emilia types. This has to be Vij’s mom’s idea. She’s always penciling in extracurriculars for his future resume. It’s not easy having two older sisters in Ivy League schools and a younger one who reads the dictionary for fun. An afternoon at Vij’s house makes me glad I’m an only child.

Vij bumps my shoulder with his. “You ready to make history, man?”

“Ummm.” It’s not like I had dreams of being cool. Mom always talks about the importance of setting “attainable goals.” Coolness is not an attainable goal for me. And I’ve come to terms with it. But this is the opposite of that. Joining the newspaper staff would be like pinning a bullseye on my back and then passing out flyers advertising free target practice. Suddenly, I am much less comfortable at this table.

“Here it is!” Emilia yells, holding up her phone and rescuing me from Vij’s stare. I could hug her, except she looks like the kind that can and will throw a punch.

“Let me see,” Jack or Gray says.

Emilia passes over her phone. The twins say “uhhh?” together at the exact same time. “Give it, Jack,” Vij says, and takes it from the twin with the scar over his eyebrow. I make a mental note.

“Ummm, no offense, Em, but what am I looking at here?” he asks.

Emilia comes around the table to stand behind us.

“That’s a picture of the parking lot!” she informs us.

“Well, yes. And?” Emilia grabs the phone from him and swipes left, hard.

“And… this is the same red Volvo in the handicapped spot without proper licensure,” she adds, holding it up an inch from his face.

She watches us and waits. For what, I have no idea. When we just sit there, she yanks her ponytail tighter and sighs like my mom.

“That’s illegal,” she explains.

I know it’s a huge mistake before it happens, but everyone knows you can’t stop an eye roll midroll. When she catches me, her glare could melt bones.

“What a lovely addition to our table,” she quips. “Thanks a lot, Vij.”

So, if we’re rating things on a first-day scale, similar to the pain scale at the doctor’s office, one being “I am now king of the school” and ten being “I have to change my name and relocate ASAP,” English and Spanish were solid fours—not terrible, mostly tolerable. Algebra is teetering on a seven with the specter of Mr. Wahl looming for the next nine months. Lunch would have been a three (I ate with other humans who did not try to see if I fit in the trash can), except for the newspaper invite, which will get me thrown in a trash can, so I’m sitting at a solid seven. Emilia would probably say eleven.

But none of that matters, because I am about to enter the most painful part of all: physical education. Gym is the foundation on which the house of bullying was built. Hey kid, you’re about eye-level with everyone else’s elbow, right? Let’s shoot some hoops. Your legs are half the size of everyone else’s? Go line up. It’s relay races. Tug-of-war? We’ll put you in the middle where you can dangle like dead weight. Not even enough dead weight to count.

The locker room reeks of sweat and farts and floor varnish. I find my name along the row. Vij’s locker is on the other side of the room, so I’m standing by myself, trying to shove my sweatshirt on top of my jeans and close the door before everything falls out again, when a hand snakes out and slams it shut. I yank my fingers away just in time.

“Need a little help there, bro?”

A giant has found its way into the locker room.

A huge kid with the beginnings of facial hair smirks at me. His breath smells of pizza and Dr Pepper. I recognize him from math class. His name is Chance Sullivan, and he’s on the basketball team. How could you name your kid “Chance” and ever expect him to be taken seriously?

He looms, serious enough. I start to swallow convulsively. There’s not enough air in the room or spit in my mouth.

“How’d a third grader get in here?” he asks the room at large, and laughs. It is the noise of a frog burping. It’s as dumb an insult as it sounds, and I have heard so much worse. Huge-O. Tiny Tot. Lowrider. Smurfette. Bite-Size. Runt. Hobbit. Oompa Loompa. Arm Rest was the worst because it invited physical contact. As bullies go, Chance is an amateur. For a second his words just hang there, and I pray it’ll come to nothing. Then one kid who’s sitting on the bench and tying his shoes chuckles. That’s all it takes, one laugh, to make it legit. I want to crawl into my locker and hide under my sweatshirt.

“Whatever,” I mumble.

“What’s that?” Chance leans down and I shrink back, which is a mistake. Never retreat.

“Don’t worry about it, bud.” Chance pats me not-so-kindly on the shoulder. “You still got a few years for that voice to drop.” His own voice is the rumble of a motor, a pack-a-day man, a superhero. I will not cry. I just hope I don’t run. In the general allotment of “fight or flight,” I only got flight.

Vij comes to my rescue. I am both thankful and irritated.

“Let’s go,” he says without looking at Chance.

“Vijay, my man. I was just introducing myself to your cousin.” Chance is jolly now, like we’re old pals. Of course he knows we’re cousins. It’s a small school. Everybody probably already knows my pants size too. Vij and I say nothing. Chance turns to go. I think it’s over. Then he reaches out his sweaty hand and rubs my head. “For luck,” he says. “Leprechauns are lucky, right?” So original. Call the tiny Irish kid a leprechaun.

I imagine myself saying something, fighting back: Better a leprechaun than a troll or At least I remembered deodorant. It could be the beginning of a new era. Hugo O’Connell saves himself and saves the day. No more “small” talk. I’d be funny and popular and living my best life. Finally one of the cool kids. But in the end, I just stand there, humiliation fizzing in my chest while everyone else files out. Vij puts his hand on my shoulder. I shake it off.

“Don’t worry about it,” he says when we’re alone. “It’s just ’cause you’re new.”

But we both know that’s a lie.

Recenzii

* "Sumner perfectly captures the fickle nature of middle school social status and the gnawing pain of betrayal. . . This is a strong work about finding your people, learning to apologize, and the rewards of self-respect. The pitch-perfect voice and everyday bravery of this middle school survivor are not to be missed."

"As in Roll With It (2019), Sumner winningly explores themes of acceptance and physical and emotional vulnerabilities."

"Sumner renders Hugo’s journey toward embracing his strengths and recognizing the power of kindness painfully believable, not shying from his own hurtful and immature behavior as he learns valuable lessons about friendship and family."

"As in Roll With It (2019), Sumner winningly explores themes of acceptance and physical and emotional vulnerabilities."

"Sumner renders Hugo’s journey toward embracing his strengths and recognizing the power of kindness painfully believable, not shying from his own hurtful and immature behavior as he learns valuable lessons about friendship and family."

Descriere

From the acclaimed author of Roll with It and Tune It Out comes a funny and moving middle-grade novel about a boy who uses his unusual talent to try to fit in at his new school.