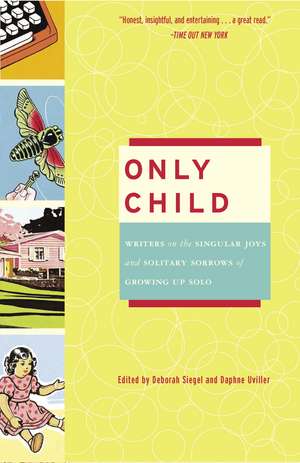

Only Child: Writers on the Singular Joys and Solitary Sorrows of Growing Up Solo

Editat de Deborah Siegel, Daphne Uvilleren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2008

In this insightful and entertaining collection, writers including Judith Thurman, Kathryn Harrison, John Hodgman, and Peter Ho Davies reflect on a lifetime of being an only. They describe what it’s like to be an only child of divorce, an only because of the death of a sibling, an only who reveled in it, or an only who didn’t. As adults searching for partners, they are faced with the unique challenge of trying to turn their family units of three into units of four, and as they watch their parents age, they come face-to-face with the onus of being their families’ sole historians.

Whether you’re an only child, the partner or spouse of an only, a parent pondering whether to stop at one, or a curious sibling, Only Child offers a look behind the scenes and into the hearts of twenty-one smart and sensitive writers as they reveal the truth about growing up–and being a grown-up–solo.

Preț: 115.34 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 173

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.07€ • 24.05$ • 18.60£

22.07€ • 24.05$ • 18.60£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 02-16 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307238078

ISBN-10: 0307238075

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 0307238075

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

DEBORAH SIEGEL is the author of Sisterhood, Interrupted: From Radical Women to Grrls Gone Wild. She has written for Psychology Today and The Progressive and is a founding editor of The Scholar & Feminist Online.

DAPHNE UVILLER is a former editor and current contributing writer to Time Out New York. She has been published in the Washington Post, the New York Times, Newsday, The Forward, Allure, and Self. Both editors are only children.

From the Hardcover edition.

DAPHNE UVILLER is a former editor and current contributing writer to Time Out New York. She has been published in the Washington Post, the New York Times, Newsday, The Forward, Allure, and Self. Both editors are only children.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Postcards to Myself

Peter Terzian

When I was in second grade, I brought home books from my elementary-school library with titles like Fair Is Our Land and Beyond New England Thresholds. These books had glossy pictures of colonial towns with sheep grazing in the commons and forts where cannons were fired on the hour. I pleaded to be taken to these places, to monuments, writers' homes, battlefields, and living-history museums. I planned prospective itineraries on road maps and selected appropriately priced motels from our AAA Guide. I had no brothers and sisters whose wishes needed to be taken into account. How could my parents refuse?

We were a family of four: my mother, my father, me, and my mother's mother, who moved in with us not long after I was born. I grew up thinking of my grandmother as a sort of surrogate sibling. I was her only grandson, and she doted on me, pouring my cereal each morning and picking up my toys every evening. When I came home from school, we would sit together on the lumpy couch in the den and watch children's public television shows. But my mother and father didn't invite my grandmother to join us on our vacations, and she didn't ask to come along. Perhaps there was a silent understanding that travel allowed my parents and me to revert temporarily to our original, two-generational state. We became a family of three.

On the road, I would sit alone in the back of the car, surrounded by pillows and books and stuffed animals. There was no one to fight with, no one to draw an invisible do-not-cross line down the middle of the seat with, no one to play billboard lotto with. Still, I didn't miss having a sibling. My parents were up front, taking turns behind the wheel and reading the newspaper. We all looked out the windows at the passing landscape. I read out loud descriptions of the attractions we'd soon be seeing, from brochures that I had written away for months in advance. I rode in a bubble of contentment, happy to be away from my school and our street and our small domestic worries. Still, I counted the hours until our arrival- how long it would take to check in to our hotel, how long before we came across a souvenir stand, how long before I spotted a rack of postcards.

I bought my first postcards- on our first family vacation, a long weekend in Washington, D.C. It was 1975, and I was feverish with the American Bicentennial. Every morning, I stood at the living-room window and recited the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag in our next-door neighbor's yard. I sang patriotic songs around the house and wore a plastic tricornered hat at the dinner table. I helped my parents pick out wallpaper for my bedroom- a pattern of colonial cartography. It was my greatest wish to visit the District of Columbia. I wanted to see the marble of the Capitol building shining like polished teeth. I wanted to walk the Mall.

My parents were only too happy to grant this wish. My mother was a childhood bookworm. My father was a second-generation Armenian-American who grew up with other children of immigrants. English-language books were scarce in his early life, and his parents placed little value on education. His father told him that he should take up a trade. But the GI Bill allowed my father to go to college, and he became a high-school math teacher. His great hope was that his son would be a scholar. And now, here I was, begging for a trip that most kids my age would have thought perilously close to schoolwork.

We drove to Washington, a seven-hour trip from our home in upstate New York. At the Jefferson Memorial, we admired the statue of the president. I read aloud the inscriptions on the walls, excerpts of his letters and writings; some of these passages I already knew by heart. My father's face showed boundless pride as I precociously sounded out the long words: tyranny . . . inalienable . . . providence . . .

I was to be rewarded. Taking me by the hand, my father led me down a staircase to a souvenir shop in the basement. There he brought me to a white pegboard display, with rows of little wire racks that held thick stacks of small, brilliantly colored pictures. These were postcards, my father explained. Did I want any, to keep as mementos?

I wanted many, and I wanted them badly. Together we picked out about a dozen: the district's rotundas and pillared porticoes; the Washington Monument, that alien-looking obelisk; cherry blossoms surrounding the Tidal Basin; aerial views of the green-and-white city. One card was a grid of about twenty miniature scenes, a postcard like a quilt of smaller postcards. (This was soon to become my most cherished specimen.) My father handed a dollar- all this for a single dollar!- to the kindly white-haired woman behind the counter. I clasped the bag of postcards for the rest of the day until it was wrinkled and fuzzy with the sweat from my hands.

Back at the hotel, I fingered the scalloped edges of these cards; they were shaped like rectangular pieces of lace. Each had a white bar across the bottom that identified in elegant script the subject of the picture. The skies were deep blue, bluer than any real sky, with cottony clouds. The buildings and monuments sparkled. The places in these photographs were like none I had ever seen. I wanted to enter these pictures, where everything was perfect. I imagined living inside a postcard.

When we returned home a few days later, I showed the postcards to my grandmother. She gave me a clear plastic shoe box, embossed with a pattern of daisies and topped with a butter-yellow lid, to store them in. I placed the box on a shelf above my desk and admired the cards through the transparent flowers. There were too few postcards for such a long box; they fell over any time I moved it. It was clear to me that I needed to fill the box.

Over time my collection grew steadily. One spring, we took a trip to Florida, to Walt Disney World and south to Miami, with stops at roadside attractions in between. In gift shops, I skipped over postcards of bikinied women on generic-looking beaches and found parrots and pyramids of rapturous water-skiers. We spent a long weekend in Boston, following the Freedom Trail in a pelting rainstorm that inverted our umbrellas, my accumulating packets of postcards sheltered deep under my layers of coat and sweater. We trekked across the state to Niagara Falls, the banks thick with honky-tonk shops and wax museums that I found wildly alluring.

My parents were supportive of my new habit. Postcard hoarding was inexpensive and educational; what was there to object to? My collecting impulse was abetted by my grandmother, who belonged to a local senior-citizens group. The seniors went on "mystery trips" every few months. I was fascinated by the idea of older people boarding a bus for a day's excursion, not knowing where they were going until they were on the highway, when the group organizer would announce their destination. These places never sounded very exciting- a large shopping mall on the outskirts of a run-down city, an old-fashioned general store that sold jam and wicker items. But when my grandmother returned in the evening, she always had two or three additions for my postcard box.

I fiddled with my cards obsessively. I would bring the box out to the front porch and sit on a folding lawn chair, flipping through them. I would count them, then count them again. My father gave me a set of index-card dividers, which I used to separate them into geographic categories. I was a child; naturally, I wanted to play with my postcards. But I knew that the neighborhood kids my age didn't play like this. No one else had this sort of toy.

I decided to write on one. The blank spaces on the backs beckoned. I turned over the best one, the multipictured card from Washington. Who could I write to? I couldn't think of anyone; I would write to myself. "Dear Peter," I began. Then I paused- I had nothing to say. I put the card back, ashamed. I had marred my prized possession. Later, I would wince whenever I came across the childish scrawl.

Sometimes I glimpsed the difference between my world- my solitude, my unique live-in grandparent, my idiosyncratic obsessions- and the other world, the world of nuclear families, of brothers and sisters. Next door to us lived Josh and Jenny, twins two years older than me, who lived in a house of shared toys and board games. I wondered, Did the whole family play these games together after dinner, like they did on Saturday morning television commercials? I tried to cajole my family into sitting down to Monopoly or Clue. But my grandmother couldn't understand the rules, or my father would grow restless. "I don't like board games," he would say with a grin, relishing the coming pun. "They bore me."

One day I heard the twins talking about how they were going to make paper masks that evening with their parents in preparation for a church youth-group event. I thought longingly about the mask-making all afternoon. When it grew dark I pulled a book of craft projects from my bookcase and crossed the lawn between the two houses. Jenny answered the bell. "I have this book, it might have instructions for how to make masks," I explained. "We don't need it," she said. I put one foot up on the doorjamb, as if to inch my way into the house. "What are you doing?" she asked icily. She closed the door in my face, pushing me back onto the porch.

I came to realize there were things I could do outside the house and things I could only do inside. Outside, I tried to join other kids in made-up games of War and Spaceship, making machine-gun and siren sounds. Inside, I quietly tended my postcards like a garden.

This division, unfortunately, wasn't always so neat. I knew, for example, that I couldn't bring my postcard box to school. But for a while, I would stash a few cards into a large blue zippered pencil case. I didn't dare take them out; rather, when I was in need of comfort in the middle of class, I would pretend that I needed a new or different pencil, and peek in the bag at the hidden image.

When I turned ten, my parents and I took a monthlong trip to California. My collection nearly doubled. So many new attractions: giant trees! Cable cars! My father's second cousin, a pistachio farmer outside of Fresno, invited us to stay at his ranch for a month; he and his wife and their two daughters, who were a few years my senior, traveled with us up and down the state. Kristi and Katrina were at first curious about my interest. They even began picking out cards here and there for themselves. But as the weeks went by and the long hours in the family's VW van wore everyone down, my obsession became an annoyance. I would spot a display of postcards on the sidewalk outside a cheap souvenir store and bring the clan to a halt while I squeaked the revolving rack around, hunting for fresh Kodachrome. My cousins blew at their bangs and tapped the toes of their clogs to dramatize their impatience.

Later that year, when we moved to a new neighborhood, I refused to pack my postcards with my toys and books. Instead, I sat in the cab of the moving truck on the way to the new house with my shoe box in my lap. I had a new favorite card that I proudly displayed through the transparent front of the box. The words "Greetings from the Golden State" were emblazoned over a triptych of the Sacramento Statehouse, the Golden Gate Bridge, and Half Dome.

That fall, as I entered junior high school, I grieved over our California trip. I tried desperately to recapture it. In English class, I wrote a poem about horseback riding in Yosemite. ("The horse_/_clopped_/_on the beaten path_/_far behind_/_the tour group.") At home, I decided to compose my life's story. The first chapter was a day-by-day recounting of our month in California. ("We drove along the Pismo state beach for about twenty minutes. We had dinner at McDonald's. I had a banana shake. The next day we checked out of our motel.") I started a second chapter that began with my birth and proceeded chronologically from there, but I quickly lost interest. The non-California periods of my life didn't seem so exciting anymore.

My parents bought a small business that took up much of their time. We didn't go on many vacations anymore. I was growing older and fitting into my new body awkwardly. My feet hurt, my posture was bad, my rear end stuck out. I didn't know what clothes to wear. My glasses, Coke-bottle lenses in aviator frames, were usually covered in dust and dandruff. I was confused about music. The junior-high-school walls were tattooed in blue pen with strange logos- Zoso, AC/DC. I only knew that these had something to do with devilish bands led by hairy men.

I became a walking target for jocks and burnouts. I was afraid to use the boys' room. I wished I had an older sibling, a sister with long straight hair, who would tell me what clothes to buy and what music to listen to. She would miraculously swoop in to fend off any would-be tormentors.

But what if I had a sister who became a jock or a burnout herself? What if she joined the ranks of my tormentors? I imagined an additional presence in our small suburban home, another person's voice and smells; long hair in the sink. She would be all-seeing, all-knowing. And I would be self-conscious about playing with postcards in front of her. She might make fun of them. Worse, she might tell my classmates about them.

I entertained a more horrific thought: She might actually like my postcards and want to play with them herself. What if she mishandled them? Or left them out in the backyard? Or got peanut butter on them?

I grew increasingly nostalgic for past trips. I longed to be elsewhere, far from home and school, secure with my parents, seeing new sights, breathing different air. We weren't traveling, but I searched for more postcards. At the stationery store in the mall, I'd buy cards of our city and the minor points of interest nearby: a bridge just outside of town, named after a Polish Revolutionary War general, on the highway to the Canadian border; bicyclists in a dull-looking park by the river; the large plaster dog, a local landmark, on the roof of an old hi-fi factory.

From the Hardcover edition.

Peter Terzian

When I was in second grade, I brought home books from my elementary-school library with titles like Fair Is Our Land and Beyond New England Thresholds. These books had glossy pictures of colonial towns with sheep grazing in the commons and forts where cannons were fired on the hour. I pleaded to be taken to these places, to monuments, writers' homes, battlefields, and living-history museums. I planned prospective itineraries on road maps and selected appropriately priced motels from our AAA Guide. I had no brothers and sisters whose wishes needed to be taken into account. How could my parents refuse?

We were a family of four: my mother, my father, me, and my mother's mother, who moved in with us not long after I was born. I grew up thinking of my grandmother as a sort of surrogate sibling. I was her only grandson, and she doted on me, pouring my cereal each morning and picking up my toys every evening. When I came home from school, we would sit together on the lumpy couch in the den and watch children's public television shows. But my mother and father didn't invite my grandmother to join us on our vacations, and she didn't ask to come along. Perhaps there was a silent understanding that travel allowed my parents and me to revert temporarily to our original, two-generational state. We became a family of three.

On the road, I would sit alone in the back of the car, surrounded by pillows and books and stuffed animals. There was no one to fight with, no one to draw an invisible do-not-cross line down the middle of the seat with, no one to play billboard lotto with. Still, I didn't miss having a sibling. My parents were up front, taking turns behind the wheel and reading the newspaper. We all looked out the windows at the passing landscape. I read out loud descriptions of the attractions we'd soon be seeing, from brochures that I had written away for months in advance. I rode in a bubble of contentment, happy to be away from my school and our street and our small domestic worries. Still, I counted the hours until our arrival- how long it would take to check in to our hotel, how long before we came across a souvenir stand, how long before I spotted a rack of postcards.

I bought my first postcards- on our first family vacation, a long weekend in Washington, D.C. It was 1975, and I was feverish with the American Bicentennial. Every morning, I stood at the living-room window and recited the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag in our next-door neighbor's yard. I sang patriotic songs around the house and wore a plastic tricornered hat at the dinner table. I helped my parents pick out wallpaper for my bedroom- a pattern of colonial cartography. It was my greatest wish to visit the District of Columbia. I wanted to see the marble of the Capitol building shining like polished teeth. I wanted to walk the Mall.

My parents were only too happy to grant this wish. My mother was a childhood bookworm. My father was a second-generation Armenian-American who grew up with other children of immigrants. English-language books were scarce in his early life, and his parents placed little value on education. His father told him that he should take up a trade. But the GI Bill allowed my father to go to college, and he became a high-school math teacher. His great hope was that his son would be a scholar. And now, here I was, begging for a trip that most kids my age would have thought perilously close to schoolwork.

We drove to Washington, a seven-hour trip from our home in upstate New York. At the Jefferson Memorial, we admired the statue of the president. I read aloud the inscriptions on the walls, excerpts of his letters and writings; some of these passages I already knew by heart. My father's face showed boundless pride as I precociously sounded out the long words: tyranny . . . inalienable . . . providence . . .

I was to be rewarded. Taking me by the hand, my father led me down a staircase to a souvenir shop in the basement. There he brought me to a white pegboard display, with rows of little wire racks that held thick stacks of small, brilliantly colored pictures. These were postcards, my father explained. Did I want any, to keep as mementos?

I wanted many, and I wanted them badly. Together we picked out about a dozen: the district's rotundas and pillared porticoes; the Washington Monument, that alien-looking obelisk; cherry blossoms surrounding the Tidal Basin; aerial views of the green-and-white city. One card was a grid of about twenty miniature scenes, a postcard like a quilt of smaller postcards. (This was soon to become my most cherished specimen.) My father handed a dollar- all this for a single dollar!- to the kindly white-haired woman behind the counter. I clasped the bag of postcards for the rest of the day until it was wrinkled and fuzzy with the sweat from my hands.

Back at the hotel, I fingered the scalloped edges of these cards; they were shaped like rectangular pieces of lace. Each had a white bar across the bottom that identified in elegant script the subject of the picture. The skies were deep blue, bluer than any real sky, with cottony clouds. The buildings and monuments sparkled. The places in these photographs were like none I had ever seen. I wanted to enter these pictures, where everything was perfect. I imagined living inside a postcard.

When we returned home a few days later, I showed the postcards to my grandmother. She gave me a clear plastic shoe box, embossed with a pattern of daisies and topped with a butter-yellow lid, to store them in. I placed the box on a shelf above my desk and admired the cards through the transparent flowers. There were too few postcards for such a long box; they fell over any time I moved it. It was clear to me that I needed to fill the box.

Over time my collection grew steadily. One spring, we took a trip to Florida, to Walt Disney World and south to Miami, with stops at roadside attractions in between. In gift shops, I skipped over postcards of bikinied women on generic-looking beaches and found parrots and pyramids of rapturous water-skiers. We spent a long weekend in Boston, following the Freedom Trail in a pelting rainstorm that inverted our umbrellas, my accumulating packets of postcards sheltered deep under my layers of coat and sweater. We trekked across the state to Niagara Falls, the banks thick with honky-tonk shops and wax museums that I found wildly alluring.

My parents were supportive of my new habit. Postcard hoarding was inexpensive and educational; what was there to object to? My collecting impulse was abetted by my grandmother, who belonged to a local senior-citizens group. The seniors went on "mystery trips" every few months. I was fascinated by the idea of older people boarding a bus for a day's excursion, not knowing where they were going until they were on the highway, when the group organizer would announce their destination. These places never sounded very exciting- a large shopping mall on the outskirts of a run-down city, an old-fashioned general store that sold jam and wicker items. But when my grandmother returned in the evening, she always had two or three additions for my postcard box.

I fiddled with my cards obsessively. I would bring the box out to the front porch and sit on a folding lawn chair, flipping through them. I would count them, then count them again. My father gave me a set of index-card dividers, which I used to separate them into geographic categories. I was a child; naturally, I wanted to play with my postcards. But I knew that the neighborhood kids my age didn't play like this. No one else had this sort of toy.

I decided to write on one. The blank spaces on the backs beckoned. I turned over the best one, the multipictured card from Washington. Who could I write to? I couldn't think of anyone; I would write to myself. "Dear Peter," I began. Then I paused- I had nothing to say. I put the card back, ashamed. I had marred my prized possession. Later, I would wince whenever I came across the childish scrawl.

Sometimes I glimpsed the difference between my world- my solitude, my unique live-in grandparent, my idiosyncratic obsessions- and the other world, the world of nuclear families, of brothers and sisters. Next door to us lived Josh and Jenny, twins two years older than me, who lived in a house of shared toys and board games. I wondered, Did the whole family play these games together after dinner, like they did on Saturday morning television commercials? I tried to cajole my family into sitting down to Monopoly or Clue. But my grandmother couldn't understand the rules, or my father would grow restless. "I don't like board games," he would say with a grin, relishing the coming pun. "They bore me."

One day I heard the twins talking about how they were going to make paper masks that evening with their parents in preparation for a church youth-group event. I thought longingly about the mask-making all afternoon. When it grew dark I pulled a book of craft projects from my bookcase and crossed the lawn between the two houses. Jenny answered the bell. "I have this book, it might have instructions for how to make masks," I explained. "We don't need it," she said. I put one foot up on the doorjamb, as if to inch my way into the house. "What are you doing?" she asked icily. She closed the door in my face, pushing me back onto the porch.

I came to realize there were things I could do outside the house and things I could only do inside. Outside, I tried to join other kids in made-up games of War and Spaceship, making machine-gun and siren sounds. Inside, I quietly tended my postcards like a garden.

This division, unfortunately, wasn't always so neat. I knew, for example, that I couldn't bring my postcard box to school. But for a while, I would stash a few cards into a large blue zippered pencil case. I didn't dare take them out; rather, when I was in need of comfort in the middle of class, I would pretend that I needed a new or different pencil, and peek in the bag at the hidden image.

When I turned ten, my parents and I took a monthlong trip to California. My collection nearly doubled. So many new attractions: giant trees! Cable cars! My father's second cousin, a pistachio farmer outside of Fresno, invited us to stay at his ranch for a month; he and his wife and their two daughters, who were a few years my senior, traveled with us up and down the state. Kristi and Katrina were at first curious about my interest. They even began picking out cards here and there for themselves. But as the weeks went by and the long hours in the family's VW van wore everyone down, my obsession became an annoyance. I would spot a display of postcards on the sidewalk outside a cheap souvenir store and bring the clan to a halt while I squeaked the revolving rack around, hunting for fresh Kodachrome. My cousins blew at their bangs and tapped the toes of their clogs to dramatize their impatience.

Later that year, when we moved to a new neighborhood, I refused to pack my postcards with my toys and books. Instead, I sat in the cab of the moving truck on the way to the new house with my shoe box in my lap. I had a new favorite card that I proudly displayed through the transparent front of the box. The words "Greetings from the Golden State" were emblazoned over a triptych of the Sacramento Statehouse, the Golden Gate Bridge, and Half Dome.

That fall, as I entered junior high school, I grieved over our California trip. I tried desperately to recapture it. In English class, I wrote a poem about horseback riding in Yosemite. ("The horse_/_clopped_/_on the beaten path_/_far behind_/_the tour group.") At home, I decided to compose my life's story. The first chapter was a day-by-day recounting of our month in California. ("We drove along the Pismo state beach for about twenty minutes. We had dinner at McDonald's. I had a banana shake. The next day we checked out of our motel.") I started a second chapter that began with my birth and proceeded chronologically from there, but I quickly lost interest. The non-California periods of my life didn't seem so exciting anymore.

My parents bought a small business that took up much of their time. We didn't go on many vacations anymore. I was growing older and fitting into my new body awkwardly. My feet hurt, my posture was bad, my rear end stuck out. I didn't know what clothes to wear. My glasses, Coke-bottle lenses in aviator frames, were usually covered in dust and dandruff. I was confused about music. The junior-high-school walls were tattooed in blue pen with strange logos- Zoso, AC/DC. I only knew that these had something to do with devilish bands led by hairy men.

I became a walking target for jocks and burnouts. I was afraid to use the boys' room. I wished I had an older sibling, a sister with long straight hair, who would tell me what clothes to buy and what music to listen to. She would miraculously swoop in to fend off any would-be tormentors.

But what if I had a sister who became a jock or a burnout herself? What if she joined the ranks of my tormentors? I imagined an additional presence in our small suburban home, another person's voice and smells; long hair in the sink. She would be all-seeing, all-knowing. And I would be self-conscious about playing with postcards in front of her. She might make fun of them. Worse, she might tell my classmates about them.

I entertained a more horrific thought: She might actually like my postcards and want to play with them herself. What if she mishandled them? Or left them out in the backyard? Or got peanut butter on them?

I grew increasingly nostalgic for past trips. I longed to be elsewhere, far from home and school, secure with my parents, seeing new sights, breathing different air. We weren't traveling, but I searched for more postcards. At the stationery store in the mall, I'd buy cards of our city and the minor points of interest nearby: a bridge just outside of town, named after a Polish Revolutionary War general, on the highway to the Canadian border; bicyclists in a dull-looking park by the river; the large plaster dog, a local landmark, on the roof of an old hi-fi factory.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Some of the onlies loathed their solitary state . . . Others reveled in the spotlight . . . But most of the entries fall somewhere in between–contented but bittersweet.”

—New York Times

“The dueling characteristics of the only child–lonely or independent? precocious or smart-mouthed? clingy or loyal?–[are] the makings . . . of a collection of twenty-one essays by various writers exploring the pleasures and paucity of a life without siblings.”

—New York Observer

“(H)onest, insightful and entertaining…these diverse essays play exceedingly well together.”

—Time Out New York

—New York Times

“The dueling characteristics of the only child–lonely or independent? precocious or smart-mouthed? clingy or loyal?–[are] the makings . . . of a collection of twenty-one essays by various writers exploring the pleasures and paucity of a life without siblings.”

—New York Observer

“(H)onest, insightful and entertaining…these diverse essays play exceedingly well together.”

—Time Out New York

Descriere

In this unprecedented collection, such writers as Judith Thurman, Kathryn Harrison, John Hodgman, and Peter Ho Davies reflect on the single, transforming episode that defined each of them as an only child.