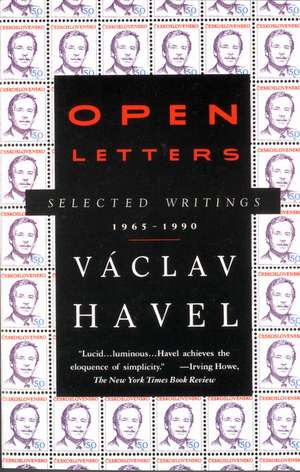

Open Letters: Selected Writings, 1965-1990

Autor Vaclav Havel Traducere de PAUL WILSONen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 1992

Preț: 97.80 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 147

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.72€ • 19.47$ • 15.69£

18.72€ • 19.47$ • 15.69£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780679738114

ISBN-10: 0679738118

Pagini: 432

Dimensiuni: 134 x 202 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Ediția:Vintage Books.

Editura: Vintage Publishing

ISBN-10: 0679738118

Pagini: 432

Dimensiuni: 134 x 202 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Ediția:Vintage Books.

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Extras

Preface

by Paul Wilson

Toronto, March 1991

I am unwilling to believe that this whole civilization is no more than a blind alley of history and a fatal error of the human spirit. More probably it represents a necessary phase that man and humanity must go through, one that man—if he survives—will ultimately, and on some higher level (unthinkable of course without the present phase) transcend.

—Václav Havel, "Thriller"

The idea of putting together a selection of Václav Havel's nondramatic writing seemed at first like a simple enough proposition. The purpose was, and remains, for this to be a companion volume to Letters to Olga, Disturbing the Peace, and his plays. Open Letters will round out the picture these other works give us of Václav Havel as dramatist, writer, thinker, and future statesman.

The problem, however, was that many of Havel's major essays and articles had already been translated and published, and some, like "The Power of the Powerless"—Havel's most penetrating analysis of the totalitarian system and how people resist it—had been widely reprinted. It still made sense to bring these essays together in a single volume, but the risk was that such a volume might not have given readers who had been following Havel's work much that was new.

Thinking about this problem, I realized that the new distinction between major and minor works in what I was trying to do was misleading. Havel's lesser-known pieces—his speeches, letters, newspaper articles, his samizdat reports meant mainly for friends, the profiles of people he admired, the conversations and interviews—provide us with the humus of this thinking and give us glimpses of the man that are sometimes missing from his more substantial works. Therefore, they belong in a book that intends to present the reader with Havel the man, not just Havel the dissident thinker.

The twenty-five items assembled here cover Václav Havel's nondramatic writing from 1965—when he was a young playwright with the Theatre on the Balustrade in Prague—to his New Year's address to Czechoslovakia on January 1, 1990, shortly after he had become the country's president. The chronological arrangement (with the exception of the first item, "Second Wind") comes naturally out of the book's purpose. Havel is, in the best sense of the word, an occasional writer; he responds, in his writing, to events, experiences, insights, arguments, states of mind. When his pieces are assembled in the order in which he wrote them, they become a chronicle both of his intellectual life, and, implicitly, of his times as well.

Many of Havel's essays were, in fact, agents of history. I don't know whether his private letter to Alexander Dubček in 1969 influenced the agonizing decision Dubček had to make at the time, but I remember clearly the deep transformation in the mood in Prague brought about by "Dear Dr. Husák," Havel's widely circulated open letter to the Czechoslovak president in 1975. This essay raised the hope that Husák's regime would one day end, made that end seem inevitable, and thus brought it closer. But the best testimony to the power of Havel's prose comes from the Polish politician and former Solidarity activist Zbygniew Bujak. In the late 1970s when Bujak was a young activist trying to organize resistance to the communist bosses in the Ursus factory near Warsaw, he became discouraged at the lack of response and began to doubt the meaning of what he was doing. Then he came across a copy of "The Power of the Powerless," by Havel. "Its ideas," he told me, "strengthened us and persuaded us that what we were doing would not evaporate without a trace, that this was the source of our power, and that one day this power would manifest itself. . . .When I look at the victories of Solidarity and of Charter 77, I see in them an astonishing fulfillment of the prophecies contained in Havel's essay."

* * *

For readers as yet unfamiliar with Havel's other work, it may be worth reviewing, briefly, the phases of life encompassed in this volume. In the earliest stage, up to the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 and its immediate aftermath, Havel was known mainly as a playwright, and only occasionally as an essayist. When he became active in public life, in the mid-1960's, he spoke chiefly as a member of the editorial board of Tvář magazine and a member of the Union of Czechoslovak Writers. His chief target was not so much communism as it was the ideology of reform communism, that "peculiar dialectical dance of truth and lies" which suggested that with certain minor adjustments, the beast that Marx conceived, Lenin unleashed, and Stalin goaded into a fury could be tamed and domesticated. In an early speech to the Writer's Union ("On Evasive Thinking") Havel talks, with remarkable prescience, about the destruction and tragedy that result when language and ideology turn away from the world, when writers avoid problems by putting them in false contexts. Later, his quarrel with the reformers becomes more specific. "On the Theme of Opposition," written during the Prague Spring of 1968, is his most openly political clash with that viewpoint.

In the 1970s, along with many of his old reform communist adversaries, Havel became an outcast and later an active dissenter. As a dramatist without a stage, he continued to write plays (some of his best, in fact, come from this period), but his impact as a playwright was now almost exclusively abroad. Inside Czechoslovakia his influence now came through his power as an essayist. He dissected aspects of the new repression, examining its effect on culture and everyday life ("Dear Dr. Husák"), on the way laws were applied ("The Trial," "Article 202," and "Article 303"), and on the growth of an "anti-political politics" in which dissidents of all hues harnessed the power of truth ("The Power of the Powerless"). He was a founding member and spokesman of the human rights "initiative" Charter 77 and the Committee to Defend the Unjustly Prosecuted, and he published his own samizdat series of books called Edice Expedice. These activities, as well as his essays, landed him in prison in 1979 where, in a remarkable series of letters to his wife Olga, he was compelled by circumstances and the prison censor to dig deeply into his own personality and beliefs and explore their broader, more philosophical implications.

The essays Havel wrote on his return from prison to 1983 reflect this deeper view of things. In "Politics and Conscience," for instance, he returns to his old themes, but in a broader context this time, arguing that the problems the world faces are rooted in "the irrational momentum of anonymous, impersonal and inhuman power," and that while the crisis is deepest and most acute in communist countries, it is a worldwide phenomenon. In the meantime, Havel had become an international cause célèbre, which meant that he spent a good deal of his time talking to journalists, intellectuals, and activists from the West. This gave him the opportunity to reflect, as he does in "Anatomy of a Reticence," upon why there were such deep misunderstandings between people on either side of the Iron Curtain, when they should find themselves natural allies. Finally, when Mikhail Gorbachev, about whom Havel was initially skeptical, becomes head of the Soviet Union, a period begins in which Havel can see the end of communism, or at least its gradual transformation into something more tolerable. All his writing from the mid-eighties on is strongly colored by this conviction. In one of the last pieces in this book, "A Word About Words," he returns to an early theme: the destructive power of language, this time to examine the words that have contained the hopes and the horrors of this century. By now he has the experience of the dissident movement behind him, and he writes as someone who knows, at first hand, about "the mysterious power of words in human history."

* * *

I have excluded far more of Havel's prose than I have included. The most painful omissions were two of Havel's youthful essays, "The Anatomy of a Gag" and "On Dialectical Metaphysics," because they were too long and too abstract, and two of his later essays on theatre, because Havel had said much the same things elsewhere, more forcefully. I have included none of Haven's introductions to samizdat books or anthologies, and only one of his many profiles of friends and colleagues ("Thinking About František K.," which is more than just a reminiscence). Havel drafted countless declarations, protests, and brief public speeches, most of which are too occasional and too slight to use. Nor have I included any of the several statements he made in his own defense in court, mostly because the texts we have are not necessarily from Havel’s own hand, but rather based on clandestinely procured transcriptions. As he became better known, Havel was asked for, and granted, many interviews. Some of these provide excellent surveys of his thought, but precisely for that reason they are repetitive; thus, with two exceptions they too were excluded. Finally, in the year and a half before the “revolution” of 1989, Havel was a regular contributor to the underground (now legal) newspaper Lidové noviny. As interesting as these articles are historically, I felt they were too closely tied to specific events.

If there is one class of items I regret not being able to include, it is Havel’s polemical articles. Havel never shied away from a good debate not even when he ran the risk of alienating a colleague or disturbing the solidarity of the Charter 77 community. One important exchange was with Milan Kundera in late 1968 over the meaning of the popular resistance to the Soviet invasion—and more broadly, over how the Czechs and Slovaks view their own history. Another, in the late 1970s, was a debate with Ludvík Vaculík and Petr Pithart over the kinds of activities that were worth risking jail sentences for. In both cases, I felt it would have been unfair to publish Havel’s side of the polemic without also including the texts he was responding to.

* * *

As I write this preface, more than a year has elapsed since the miraculous and sudden collapse of communism in Central Europe. The euphoric hopes of a year ago seem dampened, though not extinguished, by the stark economic difficulties faced by the new democracies, by the resurgence of old, hard-line habits of rule in the Soviet Union, and by the war in the Middle East and its aftermath. It is a tribute to the vitality and depth of Václav Havel’s writing that, though these essays were written in a different world and a different time, the still illuminate the present. For did not Havel warn that the damage to individuals and societies left behind by totalitarianism would be worse than even its victims could imagine, and take a long time to repair? Did he not point out that the root cause of war does not lie in the weaponry that each side deploys against the other, but in the political realities of a divided world, and that the greatest danger—one that should be clearly foreseeable—comes from willful indifference to regimes that humiliate and oppress and silence their own citizens in the name of some expediency, or grand, utopian scheme? And does he not remind us, both in his words and by his example, that the starting point for change must be the human conscience at work in the “hidden sphere” of society, and that not to believe in its power, despite all the forces arrayed against it, is at the very least a matter of bad faith?

by Paul Wilson

Toronto, March 1991

I am unwilling to believe that this whole civilization is no more than a blind alley of history and a fatal error of the human spirit. More probably it represents a necessary phase that man and humanity must go through, one that man—if he survives—will ultimately, and on some higher level (unthinkable of course without the present phase) transcend.

—Václav Havel, "Thriller"

The idea of putting together a selection of Václav Havel's nondramatic writing seemed at first like a simple enough proposition. The purpose was, and remains, for this to be a companion volume to Letters to Olga, Disturbing the Peace, and his plays. Open Letters will round out the picture these other works give us of Václav Havel as dramatist, writer, thinker, and future statesman.

The problem, however, was that many of Havel's major essays and articles had already been translated and published, and some, like "The Power of the Powerless"—Havel's most penetrating analysis of the totalitarian system and how people resist it—had been widely reprinted. It still made sense to bring these essays together in a single volume, but the risk was that such a volume might not have given readers who had been following Havel's work much that was new.

Thinking about this problem, I realized that the new distinction between major and minor works in what I was trying to do was misleading. Havel's lesser-known pieces—his speeches, letters, newspaper articles, his samizdat reports meant mainly for friends, the profiles of people he admired, the conversations and interviews—provide us with the humus of this thinking and give us glimpses of the man that are sometimes missing from his more substantial works. Therefore, they belong in a book that intends to present the reader with Havel the man, not just Havel the dissident thinker.

The twenty-five items assembled here cover Václav Havel's nondramatic writing from 1965—when he was a young playwright with the Theatre on the Balustrade in Prague—to his New Year's address to Czechoslovakia on January 1, 1990, shortly after he had become the country's president. The chronological arrangement (with the exception of the first item, "Second Wind") comes naturally out of the book's purpose. Havel is, in the best sense of the word, an occasional writer; he responds, in his writing, to events, experiences, insights, arguments, states of mind. When his pieces are assembled in the order in which he wrote them, they become a chronicle both of his intellectual life, and, implicitly, of his times as well.

Many of Havel's essays were, in fact, agents of history. I don't know whether his private letter to Alexander Dubček in 1969 influenced the agonizing decision Dubček had to make at the time, but I remember clearly the deep transformation in the mood in Prague brought about by "Dear Dr. Husák," Havel's widely circulated open letter to the Czechoslovak president in 1975. This essay raised the hope that Husák's regime would one day end, made that end seem inevitable, and thus brought it closer. But the best testimony to the power of Havel's prose comes from the Polish politician and former Solidarity activist Zbygniew Bujak. In the late 1970s when Bujak was a young activist trying to organize resistance to the communist bosses in the Ursus factory near Warsaw, he became discouraged at the lack of response and began to doubt the meaning of what he was doing. Then he came across a copy of "The Power of the Powerless," by Havel. "Its ideas," he told me, "strengthened us and persuaded us that what we were doing would not evaporate without a trace, that this was the source of our power, and that one day this power would manifest itself. . . .When I look at the victories of Solidarity and of Charter 77, I see in them an astonishing fulfillment of the prophecies contained in Havel's essay."

* * *

For readers as yet unfamiliar with Havel's other work, it may be worth reviewing, briefly, the phases of life encompassed in this volume. In the earliest stage, up to the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 and its immediate aftermath, Havel was known mainly as a playwright, and only occasionally as an essayist. When he became active in public life, in the mid-1960's, he spoke chiefly as a member of the editorial board of Tvář magazine and a member of the Union of Czechoslovak Writers. His chief target was not so much communism as it was the ideology of reform communism, that "peculiar dialectical dance of truth and lies" which suggested that with certain minor adjustments, the beast that Marx conceived, Lenin unleashed, and Stalin goaded into a fury could be tamed and domesticated. In an early speech to the Writer's Union ("On Evasive Thinking") Havel talks, with remarkable prescience, about the destruction and tragedy that result when language and ideology turn away from the world, when writers avoid problems by putting them in false contexts. Later, his quarrel with the reformers becomes more specific. "On the Theme of Opposition," written during the Prague Spring of 1968, is his most openly political clash with that viewpoint.

In the 1970s, along with many of his old reform communist adversaries, Havel became an outcast and later an active dissenter. As a dramatist without a stage, he continued to write plays (some of his best, in fact, come from this period), but his impact as a playwright was now almost exclusively abroad. Inside Czechoslovakia his influence now came through his power as an essayist. He dissected aspects of the new repression, examining its effect on culture and everyday life ("Dear Dr. Husák"), on the way laws were applied ("The Trial," "Article 202," and "Article 303"), and on the growth of an "anti-political politics" in which dissidents of all hues harnessed the power of truth ("The Power of the Powerless"). He was a founding member and spokesman of the human rights "initiative" Charter 77 and the Committee to Defend the Unjustly Prosecuted, and he published his own samizdat series of books called Edice Expedice. These activities, as well as his essays, landed him in prison in 1979 where, in a remarkable series of letters to his wife Olga, he was compelled by circumstances and the prison censor to dig deeply into his own personality and beliefs and explore their broader, more philosophical implications.

The essays Havel wrote on his return from prison to 1983 reflect this deeper view of things. In "Politics and Conscience," for instance, he returns to his old themes, but in a broader context this time, arguing that the problems the world faces are rooted in "the irrational momentum of anonymous, impersonal and inhuman power," and that while the crisis is deepest and most acute in communist countries, it is a worldwide phenomenon. In the meantime, Havel had become an international cause célèbre, which meant that he spent a good deal of his time talking to journalists, intellectuals, and activists from the West. This gave him the opportunity to reflect, as he does in "Anatomy of a Reticence," upon why there were such deep misunderstandings between people on either side of the Iron Curtain, when they should find themselves natural allies. Finally, when Mikhail Gorbachev, about whom Havel was initially skeptical, becomes head of the Soviet Union, a period begins in which Havel can see the end of communism, or at least its gradual transformation into something more tolerable. All his writing from the mid-eighties on is strongly colored by this conviction. In one of the last pieces in this book, "A Word About Words," he returns to an early theme: the destructive power of language, this time to examine the words that have contained the hopes and the horrors of this century. By now he has the experience of the dissident movement behind him, and he writes as someone who knows, at first hand, about "the mysterious power of words in human history."

* * *

I have excluded far more of Havel's prose than I have included. The most painful omissions were two of Havel's youthful essays, "The Anatomy of a Gag" and "On Dialectical Metaphysics," because they were too long and too abstract, and two of his later essays on theatre, because Havel had said much the same things elsewhere, more forcefully. I have included none of Haven's introductions to samizdat books or anthologies, and only one of his many profiles of friends and colleagues ("Thinking About František K.," which is more than just a reminiscence). Havel drafted countless declarations, protests, and brief public speeches, most of which are too occasional and too slight to use. Nor have I included any of the several statements he made in his own defense in court, mostly because the texts we have are not necessarily from Havel’s own hand, but rather based on clandestinely procured transcriptions. As he became better known, Havel was asked for, and granted, many interviews. Some of these provide excellent surveys of his thought, but precisely for that reason they are repetitive; thus, with two exceptions they too were excluded. Finally, in the year and a half before the “revolution” of 1989, Havel was a regular contributor to the underground (now legal) newspaper Lidové noviny. As interesting as these articles are historically, I felt they were too closely tied to specific events.

If there is one class of items I regret not being able to include, it is Havel’s polemical articles. Havel never shied away from a good debate not even when he ran the risk of alienating a colleague or disturbing the solidarity of the Charter 77 community. One important exchange was with Milan Kundera in late 1968 over the meaning of the popular resistance to the Soviet invasion—and more broadly, over how the Czechs and Slovaks view their own history. Another, in the late 1970s, was a debate with Ludvík Vaculík and Petr Pithart over the kinds of activities that were worth risking jail sentences for. In both cases, I felt it would have been unfair to publish Havel’s side of the polemic without also including the texts he was responding to.

* * *

As I write this preface, more than a year has elapsed since the miraculous and sudden collapse of communism in Central Europe. The euphoric hopes of a year ago seem dampened, though not extinguished, by the stark economic difficulties faced by the new democracies, by the resurgence of old, hard-line habits of rule in the Soviet Union, and by the war in the Middle East and its aftermath. It is a tribute to the vitality and depth of Václav Havel’s writing that, though these essays were written in a different world and a different time, the still illuminate the present. For did not Havel warn that the damage to individuals and societies left behind by totalitarianism would be worse than even its victims could imagine, and take a long time to repair? Did he not point out that the root cause of war does not lie in the weaponry that each side deploys against the other, but in the political realities of a divided world, and that the greatest danger—one that should be clearly foreseeable—comes from willful indifference to regimes that humiliate and oppress and silence their own citizens in the name of some expediency, or grand, utopian scheme? And does he not remind us, both in his words and by his example, that the starting point for change must be the human conscience at work in the “hidden sphere” of society, and that not to believe in its power, despite all the forces arrayed against it, is at the very least a matter of bad faith?

Recenzii

"Brilliant and perceptive analyses...of the abuse of power by bureaucracies driven by cynical self-interest." -- Boston Globe

"An inspiring collection...a fitting tribute to a cultural and political hero, and a valuable resource for anyone seeking reassurance that the principles of democracy are still cherished in our time." -- Kirkus Reviews

"Havel's essays...show a complex political and moral sensibility. [Writing] with wonderful clarity and directness, he has a rare gift for metaphor and example. He can capture, with a phrase or a word, the dishonesty of an era."

-- Times Literary Supplement

"An inspiring collection...a fitting tribute to a cultural and political hero, and a valuable resource for anyone seeking reassurance that the principles of democracy are still cherished in our time." -- Kirkus Reviews

"Havel's essays...show a complex political and moral sensibility. [Writing] with wonderful clarity and directness, he has a rare gift for metaphor and example. He can capture, with a phrase or a word, the dishonesty of an era."

-- Times Literary Supplement

Descriere

The 25 years' worth of essays, letters, interviews, and reportage collected in this historic volume portray Havel's evolution from a modestly known playwright with the courage to criticize his country's dictator to his election as President of Czechslovakia. hero".--Kirkus Reviews.

Notă biografică

Václav Havel was born in Czechoslovakia in 1936. His plays have been produced around the world, and he is the author of many influential essays on totalitarianism and dissent. He was a founding spokesman for Charter 77 and served as president of the Czech Republic until 2003. He died in 2011 at the age of 75.