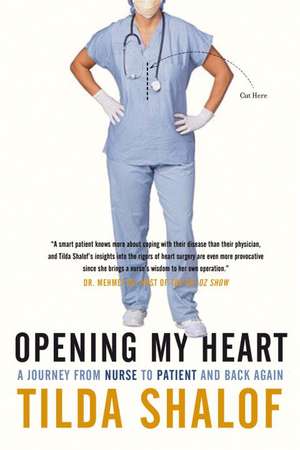

Opening My Heart: A Journey from Nurse to Patient and Back Again

Autor Tilda Shalofen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2012

Tilda’s story takes readers from the diagnosis through all her fears and concerns, the or, her stay in the icu, the cardiac ward, recovery at home, rehabilitation, and ultimately, her return to work in the hospital armed with new insights on the patient’s perspective. She learned more in her week-long stay as a patient than in all her years caring for the critically ill, especially about trust and working in partnership with her caregivers.

In Opening My Heart, Shalof expertly weaves recollections from her career and accounts of other nurses’ experiences into her own story, creating the perfect marriage between fascinating clinical detail and a personal journey of healing. Throughout it all is Shalof’s warm, friendly voice and humorous outlook. Nurses everywhere and anyone who’s ever been a hospital patient, or who is currently hospitalized or who might be one day (and those who love them!), will be empowered, enlightened, comforted, and entertained by this book.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 109.80 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 165

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.01€ • 21.83$ • 17.45£

21.01€ • 21.83$ • 17.45£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780771079894

ISBN-10: 0771079893

Pagini: 317

Dimensiuni: 152 x 226 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

ISBN-10: 0771079893

Pagini: 317

Dimensiuni: 152 x 226 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

Notă biografică

TILDA SHALOF, RN, BScN, CNCC (C), has been a staff nurse in the Medical-Surgical Intensive Care Unit at Toronto General Hospital for over twenty years. She is the author of five books about her experiences in nursing, including A Nurse’s Story, The Making of a Nurse, and Camp Nurse, and the editor of a collection of nurse's stories, Lives in the Balance. She is an outspoken patient advocate, passionate nurse leader, public speaker, and media commentator. She lives in Toronto with her husband and their two sons.

Extras

The story of my heart begins with an earache in the night. The ear belongs to my eleven-year-old son, Max, who wakes me, head in his hands, tears welling up. Sleepy mom and hard-boiled nurse that I am, I dope him up with a slurp of purple painkiller syrup and send him back to bed. But in the morning his ear still hurts and he’s spiked a temperature, so I take him to the doctor.

The waiting room is packed. How much longer until our turn? I pester the receptionist, but she’s too busy to answer. Hovering around the front desk, I scan the rack of doctors’ business cards. Three general practitioners and an asthma specialist share this office. Oh, a cardiologist, too, and I pocket one of his cards. Some people collect stamps, antiques, or lovers. I collect cardiologists ߝ a hobby of mine for years.

Eventually, we get to see Dr. Ivor Teitelbaum. He’s my husband’s doctor, and Max and his older brother, Harry’s, doctor, but not mine. I don’t go to doctors.

Ivor is a handsome, smartly dressed, young-looking middleaged guy with an old-school manner. Always relaxed, he never rushes us along, despite the bustling waiting room. He examines Max, then offers me his otoscope so I can look into the ear canal myself and see the bulging, inflamed tympanic membrane, severe enough for Ivor to prescribe an antibiotic.

We get up to go, but I pause. “This cardiologist” ߝ I wave the card at Ivor ߝ “is he any good?”

“Very.” He looks up from writing in Max’s chart. “Who needs a cardiologist?”

I shoo Max back out to the waiting room, pull up my T-shirt, and nod at the stethoscope around Ivor’s neck to remind him of my secret. I’d had to tell him so that my children’s hearts could be checked for defects. Fortunately, neither inherited my heart problem.

It takes Ivor only a quick listen and then he looks up at me, hard, grips me by the shoulder, and steers me down the hall to the office of Dr. Milutin Drobac, the cardiologist.

“She needs to be seen,” he tells the secretary, “as soon as possible.”

“It’s your lucky day,” she says. “I just got a cancellation. Tomorrow at 11:00?”

“Sorry, I can’t make it,” I say. “I’ve booked a haircut.”

She shoots me a glance. What’ll it be, your hair or your heart? Okay, heart it is.

At home I give Max the first dose of antibiotic and another dollop of grape-flavoured syrup. Soon he’s back to his usual cheery self, so I hustle him off to school, leaving me alone to muse on my funny-sounding heart. It’s only a murmur, I remind myself. What a cozy-sounding word. It almost sounds like a good thing to have.

Who wouldn’t want one? Many people have murmurs and most are normal or “innocent.” But not mine. Murmur is a term that refers to any irregularity in the heart’s blood flow, and in my case it’s due to a serious heart defect ߝ a faulty valve. It’s congenital, meaning I was born with it.

As a child, I sensed something was wrong from the get-go. The heart specialists who spoke in solemn tones and the protective, cautious way my parents held me all conveyed the message: Fragile ߝ Handle with care!

Then, around the age of ten, on one of many days off from school, I sat in a pediatrician’s office and heard him say to my parents: “In time, her condition will worsen. One day she’ll need open-heart surgery.” He probably assumed I wasn’t listening (a mistake many adults make around children) because my head was buried in a book. “No overexertion,” he warned them, “and no sports or gym classes.” For my parents, that was a perfect prescription. It dovetailed with their need to keep me close, conveniently available to help my chronically ill and depressed mother. As far as they were concerned, school was optional.

Don’t think I didn’t hear the doctor’s parting comment to my parents before he left the room: “A certain percentage of these children experience sudden death.”

That’s some experience, I thought and dove deeper into my book. I’ve always known my heart could stop suddenly, but I banished the thought. I accorded my heart no respect, never allowing myself to think I had any physical limitations. I avoided strenuous physical activities, but in my mind, I was swimming the English Channel, riding horses, even running a marathon. Meanwhile, my parents became preoccupied with their own health problems and I became a nurse so that I could focus on other people’s problems, not dare think of my own. My mo has always been to fly low on the medical radar and hope that an apple a day would keep the doctor away. (I eat a lot of apples.)

After a quiet, sedentary childhood, I threw caution to the wind and became a wild, adventurous teenager, then an active adult and energetic mother of two boys. I’ve always done whatever I wanted to do. That is, until recently. Lately, I haven’t been feeling my best. The next morning, I find myself where I always intended to never be ߝ a cardiologist’s office. First, there’s the electrocardiogram (ecg) and an echocardiogram, tests I’ve helped many patients through, so I know the ropes. I strip off my T-shirt and bra, don the blue paper gown, jump up on the table, and lie down on my back. As Cezar, a big, burly guy who’s Dr. Drobac’s technologist, does the ecg, I glimpse the tracing over his shoulder, noting that my heart is in a regular rate of sixty beats per minute. Normal sinus rhythm. So far so good.

Cezar tears the printout off the machine and attaches it to my chart with a paper clip. For the echo, I flip to my left side so that he can obtain the best view. He glides the probe around my chest, digging it in at certain landmarks for a closer look, pausing, peering at the screen, then moving on. While Cezar works, I take a look around the small room, dimly lit as a nightclub to enhance the clarity of the picture onscreen. In the corner there’s a treadmill for stress tests and a red “crash cart,” equipped with defibrillator, pacemaker, and emergency drugs.

“Ever had to use that?” I point at it. For a patient like me?

“Yup.” Cezar’s brow creases, his eyes widen then narrow, but he keeps them trained on the screen in front of him. The sound of the amplified beats of my heart fills the room.

“See anything?” I inquire, well aware that he’s not supposed to divulge anything, but I’m quite sure Cezar knows a thing or two.

“Don’t worry,” I assure him. “You can tell me. I’m a nurse ߝ an icu nurse.” He stays focused while I chatter on. “There’s a problem with the valve, isn’t there?”

Cezar pauses his probe and looks at me. “Big-time.”

But I feel fine! Well, maybe not my best . . .”How bad is it?”

“I’ll let Dr. Drobac speak with you about it.”

I get dressed and graduate to the office of Dr. Drobac, who greets me warmly. As he reviews my ecg and echo report, I check him out. He’s a tall, thin, elegant man who looks like he may have run a few marathons himself.

“You’ll never see a fat cardiologist,” my old nurse buddy Laura says. “Yet, there are many neurotic psychiatrists,” she points out. Laura has developed extensive character profiles of every medical specialty. According to her, neurologists are precise and nerdy, gastroenterologists are messy and swear a lot ߝ “think of what they do!” ߝ and all ophthalmologists have small, legible handwriting. Her theories have yet to be tested.

Dr. Drobac introduces himself and we sit down opposite each other for the “functional inquiry,” also known as the “patient interview.”

“How have you been feeling?” he starts off.

“Great! No problem!” I say. “Asymptomatic,” I feel compelled to add.

“Any history of family illnesses?”

“My mother had early onset Parkinson’s disease and manic depression. My father had type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease.”

Died from it, too, but I keep that detail to myself so as not to prejudice my case.

“Do you smoke?”

“Never!” How virtuous am I?

“Take any prescription drugs on a regular basis?

“No.” My body is a temple!

“How about recreational drugs?”

“No . . .” Well, not lately . . .

“What about alcohol?”

“Clearly, not enough.” Now that gets a laugh out of him.

“Are you a Muslim?” he asks, breaking from the script of a standard cardiac history to figure out who I am. He hasn’t quite got me pegged.

“No,” I say. “Jewish. We like to eat. But I plan to start drinking more red wine as soon as possible. In moderation, of course. Strictly for the cardio-protective properties.” Broccoli and dark chocolate, too. From now on, I’m going to do everything right. My mouth is dry, my hands are beginning to shake. “I have a feeling you’re about to give me bad news.”

“No, I’m not.” He smiles. “Not at all.”

Maybe it’s nothing. What am I worried about? I feel perfectly fine. “Any shortness of breath?” he continues.

“No . . . Not really.” Well . . . maybe, a little, now that you mention it.

“Chest pain . . .”

“No, never!”

“What about chest discomfort or tightness, or racing heartbeats?

Have you had any dizziness, light-headedness, coughing, or fainting spells?”

Now that you mention it . . . I swallow the lump in my throat and stifle the harsh, dry cough I’ve had for a few months. Suddenly, I realize it is a cardiac cough. I’d have recognized it in a patient!

“How do you feel after you walk up a flight of stairs?”

“Not great,” I admit. The truth is I haven’t been able to walk up stairs for a few months now. I’ve been avoiding them when possible, and when not, I take them slowly, pushing against the heaviness in my chest, out of breath within moments. Ditto for hills and any inclines, for that matter.

“Do you have much stress at work?”

“Not at all.” My patients do, but not me! But dare I mention that lately I can barely make it to the end of my shifts at the hospital? I am exhausted by lunchtime. “What’s wrong with Tilda lately? She’s always lying down,” I heard a nurse say in the staff lounge the other day. “I’m taking a power nap,” I said, popping up. At the end of my shifts, I’ve been dragging myself home and crashing into bed, not a drop of energy to spare.

“Are you able to do your daily activities at home?”

“Yes,” I say but don’t tell him that I couldn’t rake leaves or shovel snow this past winter and the house is a mess. I move the vacuum cleaner two sweeps and have to sit down to rest. A laundry basket full of folded clothes sits at the bottom of the stairs, too heavy for me to lift and carry to the top.

“How about sexual activity?”

“Absolutely!”

“Sex is very beneficial for heart health,” he explains.

In that case, I’ll have sex every day ߝ twice a day ߝ if necessary! (Note to self: Notify Ivan of this new treatment protocol.)

“What about exercise?”

“I have a gym membership. I’ve done a few aerobics classes . . .”

Yes, I’ve showed up at all those classes with the improbable names like Guts and Butts, Cardio Funk, and Jazzercise. But my workouts have become lame and “half-hearted.” I can’t get my heart rate up above 100 and it takes a long time to recover and return to my resting rate. Oh, and I’ll never bring a water bottle so I can have an excuse to keep stopping for a drink at the fountain to catch my breath.

“Are you keeping up with your peers?”

I haven’t heard that phrase since I was fourteen when I begged my parents for the real Adidas running shoes with three stripes that the cool kids wore, not the cheap North Stars with only two. Of course it was only a fashion statement and status symbol, since I wasn’t doing any running anyway.

Then there is my recent attempt to keep up ߝ literally. It was on a vacation to Nelson, British Columbia, to visit my friend Robyn, during a group hike up a trail on Pulpit Rock, in the foothills of the Kootenay Range, near the Rockies ߝ listed as a “gentle climb” in the guidebook. As I struggled to keep up with the pack, other friends easily strolling along faster, farther, and higher were casting back sympathetic gazes. Robyn stayed behind with me, looking worried.

“I’m taking it slow . . . so I can . . . enjoy . . . the view,” I said as I huffed and puffed, shaky and breathless. I need to make it to the top of this hill, was all I could think as I kept stopping every few feet to clutch my chest, praying I wouldn’t collapse on the way. I’m a wounded buffalo, trying to keep up with the herd. Shoot the beast! Put it out of its misery! We both knew something was wrong but didn’t discuss it. Now I allow myself to know the truth: I could have dropped dead up there on that mountaintop.

Suddenly I realize the real reason that I quit the amateur parent teacher talent show a few months ago. For my audition, I chose “A Cockeyed Optimist” from South Pacific, and mercifully they cut me off after a few bars since I sucked, but I was also too out of breath to finish. Nonetheless, they gave me a one-line solo in a songand- dance number from CATS that required me to leap onto a platform wearing a skin-tight catsuit (what was I thinking?) and belt out, “Can you ride on your broomstick to places far distant?” I couldn’t make it to broomstick. I bowed out, claiming to be too busy for rehearsals.

“So, no symptoms?” Dr. Drobac presses on.

“No.” Only a premonition of doom, which I’m having right about now.

He makes notes in my chart ߝ I now have a chart! ߝ probably jotting down unreliable historian, the damning term for patients who aren’t to be trusted. He’s recorded my symptoms ߝ what the patient reports ߝ and now moves on to the physical examination, the signs ߝ what he, the physician, observes and can measure.

We look at the ecg together. “Mild ventricular hypertrophy,” he notes and points out the deep amplitude spikes in the chest leads and explains that my left ventricle is dangerously enlarged as a result of having to work extra hard to pump blood against the resistance of a constricted aortic valve. Any icu nurse would grasp what he’s talking about, but my thinking is so jumbled I can’t follow his train of thought.

He stands up for the physical examination, ready to discover his own findings. Okay, let the objective tests be the judge. I may lie, but they won’t.

Back in my patient “uniform,” I lie down on the examining table. Dr. Drobac palpates my pulses, the carotid in my neck, brachial in my arm, radial at my wrist, femoral in my groin, popliteal at the back of my knees, and dorsalis in my feet. My pulses have always been weak and he notes that. He examines my jugular neck veins, which reflect the pressures in my heart. He places the bell of his stethoscope on my chest, closes his eyes, and listens. As I await my verdict I recall that according to Laura’s profile, in addition to being slim and fit, cardiologists are the most musical of doctors. It does make sense: they spend their days listening to the melodies of the heart and have to be exquisitely attuned to pitch, volume, rhythm, tempo, crescendos, and diminuendos.

As Dr. Drobac moves his stethoscope around my chest, I know exactly what he hears: a slushy, mushy whooshing. My heart doesn’t have the distinct sounds of a healthy cardiac cycle of contracting and relaxing; not the vigorous lub-dub of strong ventricles pumping effectively with valves opening and closing efficiently. My heart is the swish, swish of a lazy, burbling stream.

As a child, I was invited by medical schools as an interesting case study for doctors-in-training to learn abnormal heart sounds. Any first-year med student who could not correctly diagnose my obvious, loud systolic murmur would surely fail. But, when I grew up and became a nursing student myself, I stayed home from class the day they taught cardiac auscultation. We were supposed to listen to each other’s hearts and my cover would have been blown.

Back in my civvies, I sit down with Dr. Drobac, who looks me squarely in the eyes. “It’s clear why you’ve come to me now. You’re not feeling well, not keeping up. The echo shows that your valve is tight. You have severe aortic stenosis.” He gives me a moment to take that in, then says what I’ve waited all my life not to hear. “There is no doubt in my mind that you need open-heart surgery to replace your valve and to repair part of your aorta, too.”

Valve plus aorta. Cut and blow-dry. Shave and a haircut, two bits. The bottom drops out. I can’t breathe. His words catapult me to the other side. I’ve crash-landed on Planet Patient, a destination where no one ߝ but especially no nurse ߝ wants to go. Hey, don’t I get any immunity from these things happening to me?

Way over there is the doctor, talking to me from the safe side, waving and smiling from the far shore. He still seems to be thinking he’s giving me good news.

“You’ll need a cardiac angiogram first,” he continues, eager to get this party started, “to rule out coronary artery disease before surgery. . . .”

Of course. The cardiac surgeon doesn’t want to open me up and get in there only to find blocked arteries and that I need a coronary artery bypass as well as a valve replacement.

“Can this wait awhile?” I ask.

“Better to face it now, when you’re feeling relatively well, with no other co-morbidities.”

He means high blood pressure, peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery disease, hardening of the arteries, diabetes, kidney failure, a little of this, a touch of that, things waiting in the wings for most of us, one day, eventually.

“Your aorta is enlarged . . . the valve severely constricted . . . blood flow is reduced . . . ejection fraction is less than 30 per cent . . . you’re not getting adequate blood supply.”

“Could it be repaired? A minimally invasive procedure?” Could this have been avoided if I’d dealt with it earlier? That question, I wonder, but don’t dare ask since I don’t want to know the answer.

“No, your valve is too diseased. Extensive work needs to be done. It has to be replaced along with part of the aorta. It can only be fixed by opening the chest.”

But these things happen to patients! “I need time to think about it.”

“Don’t take too long.”

“When should it be done?”

“Soon. Within the next few weeks . . .”

Open-heart surgery ߝ how inconvenient! I had lots of other, much more fun plans for the summer! Taking a break from my work in the icu, spending time with Ivan and the kids, working as a camp nurse, spending time at my brother Tex’s cottage on Georgian Bay. And this was the summer we were finally going to adopt a puppy, a year after the death of our elderly dog, Rambo.

Dr. Drobac asks if I have any questions. None and many, but first I have something to tell him that’s way more urgent than any questions I might have.

“I want you to know that if I get a serious complication and don’t wake up afterward, or if I become severely brain-damaged or have to be on prolonged life support, please let me go. If it’s my time, let me go.” I do not want to be kept around beyond my useful shelf life.

I blurt out these dire directives, not bothering to explain why catastrophe is uppermost on my mind.

He’s incredulous, at a loss as to how to react to my at-the-ready disaster plan. “Have you thought this through?”

Have I ever! I think but can only nod yes to his question.

He looks perplexed, perhaps wondering how to reassure someone so anxious and somewhat irrational-sounding.

“If that’s how you feel,” he says, taking me at my word, “you should document your wishes and make sure to tell your family doctor.”

“I don’t have one.”

“Get a lawyer and write a living will. Spell out your advance directives. Let your family know your wishes for your end-of-life care. Inform the surgeon.” He shakes his head. “I don’t want to disappoint you, but you’re actually going to do very well. I wouldn’t send you for surgery if I didn’t think you were going to make it. This is a routine case.”

Surely he’s had patients who’ve died from “routine” surgery. And yes, I know, it is a good thing to be an ordinary patient with a common problem, but, see, I don’t want to be a patient at all! Walking slowly out of his office into the bright, hot summer afternoon, I’m scared out of my mind. Admittedly, there’s a tiny bit of relief, too, to be set free from this heavy secret buried inside of me all of these years. In my heart of hearts, I knew this day would come. I’ve always felt I was getting away with something, continually dodging a bullet. Up until now, I’ve managed to stay on this side of the bed, a nurse in charge of others’ care. Now I’ll be the one in the bed, nurses bending over my body, tending to me.

I’ve always been such a big champion of our health care system, here in Canada, but will I remain a loyal fan when I’m on the receiving end?

I’m also a writer of stories that have been described as “heartwarming” and “heart-wrenching.” The only thing I know for certain about the story ahead of me is that it will be heart-stopping.

From the Hardcover edition.

The waiting room is packed. How much longer until our turn? I pester the receptionist, but she’s too busy to answer. Hovering around the front desk, I scan the rack of doctors’ business cards. Three general practitioners and an asthma specialist share this office. Oh, a cardiologist, too, and I pocket one of his cards. Some people collect stamps, antiques, or lovers. I collect cardiologists ߝ a hobby of mine for years.

Eventually, we get to see Dr. Ivor Teitelbaum. He’s my husband’s doctor, and Max and his older brother, Harry’s, doctor, but not mine. I don’t go to doctors.

Ivor is a handsome, smartly dressed, young-looking middleaged guy with an old-school manner. Always relaxed, he never rushes us along, despite the bustling waiting room. He examines Max, then offers me his otoscope so I can look into the ear canal myself and see the bulging, inflamed tympanic membrane, severe enough for Ivor to prescribe an antibiotic.

We get up to go, but I pause. “This cardiologist” ߝ I wave the card at Ivor ߝ “is he any good?”

“Very.” He looks up from writing in Max’s chart. “Who needs a cardiologist?”

I shoo Max back out to the waiting room, pull up my T-shirt, and nod at the stethoscope around Ivor’s neck to remind him of my secret. I’d had to tell him so that my children’s hearts could be checked for defects. Fortunately, neither inherited my heart problem.

It takes Ivor only a quick listen and then he looks up at me, hard, grips me by the shoulder, and steers me down the hall to the office of Dr. Milutin Drobac, the cardiologist.

“She needs to be seen,” he tells the secretary, “as soon as possible.”

“It’s your lucky day,” she says. “I just got a cancellation. Tomorrow at 11:00?”

“Sorry, I can’t make it,” I say. “I’ve booked a haircut.”

She shoots me a glance. What’ll it be, your hair or your heart? Okay, heart it is.

At home I give Max the first dose of antibiotic and another dollop of grape-flavoured syrup. Soon he’s back to his usual cheery self, so I hustle him off to school, leaving me alone to muse on my funny-sounding heart. It’s only a murmur, I remind myself. What a cozy-sounding word. It almost sounds like a good thing to have.

Who wouldn’t want one? Many people have murmurs and most are normal or “innocent.” But not mine. Murmur is a term that refers to any irregularity in the heart’s blood flow, and in my case it’s due to a serious heart defect ߝ a faulty valve. It’s congenital, meaning I was born with it.

As a child, I sensed something was wrong from the get-go. The heart specialists who spoke in solemn tones and the protective, cautious way my parents held me all conveyed the message: Fragile ߝ Handle with care!

Then, around the age of ten, on one of many days off from school, I sat in a pediatrician’s office and heard him say to my parents: “In time, her condition will worsen. One day she’ll need open-heart surgery.” He probably assumed I wasn’t listening (a mistake many adults make around children) because my head was buried in a book. “No overexertion,” he warned them, “and no sports or gym classes.” For my parents, that was a perfect prescription. It dovetailed with their need to keep me close, conveniently available to help my chronically ill and depressed mother. As far as they were concerned, school was optional.

Don’t think I didn’t hear the doctor’s parting comment to my parents before he left the room: “A certain percentage of these children experience sudden death.”

That’s some experience, I thought and dove deeper into my book. I’ve always known my heart could stop suddenly, but I banished the thought. I accorded my heart no respect, never allowing myself to think I had any physical limitations. I avoided strenuous physical activities, but in my mind, I was swimming the English Channel, riding horses, even running a marathon. Meanwhile, my parents became preoccupied with their own health problems and I became a nurse so that I could focus on other people’s problems, not dare think of my own. My mo has always been to fly low on the medical radar and hope that an apple a day would keep the doctor away. (I eat a lot of apples.)

After a quiet, sedentary childhood, I threw caution to the wind and became a wild, adventurous teenager, then an active adult and energetic mother of two boys. I’ve always done whatever I wanted to do. That is, until recently. Lately, I haven’t been feeling my best. The next morning, I find myself where I always intended to never be ߝ a cardiologist’s office. First, there’s the electrocardiogram (ecg) and an echocardiogram, tests I’ve helped many patients through, so I know the ropes. I strip off my T-shirt and bra, don the blue paper gown, jump up on the table, and lie down on my back. As Cezar, a big, burly guy who’s Dr. Drobac’s technologist, does the ecg, I glimpse the tracing over his shoulder, noting that my heart is in a regular rate of sixty beats per minute. Normal sinus rhythm. So far so good.

Cezar tears the printout off the machine and attaches it to my chart with a paper clip. For the echo, I flip to my left side so that he can obtain the best view. He glides the probe around my chest, digging it in at certain landmarks for a closer look, pausing, peering at the screen, then moving on. While Cezar works, I take a look around the small room, dimly lit as a nightclub to enhance the clarity of the picture onscreen. In the corner there’s a treadmill for stress tests and a red “crash cart,” equipped with defibrillator, pacemaker, and emergency drugs.

“Ever had to use that?” I point at it. For a patient like me?

“Yup.” Cezar’s brow creases, his eyes widen then narrow, but he keeps them trained on the screen in front of him. The sound of the amplified beats of my heart fills the room.

“See anything?” I inquire, well aware that he’s not supposed to divulge anything, but I’m quite sure Cezar knows a thing or two.

“Don’t worry,” I assure him. “You can tell me. I’m a nurse ߝ an icu nurse.” He stays focused while I chatter on. “There’s a problem with the valve, isn’t there?”

Cezar pauses his probe and looks at me. “Big-time.”

But I feel fine! Well, maybe not my best . . .”How bad is it?”

“I’ll let Dr. Drobac speak with you about it.”

I get dressed and graduate to the office of Dr. Drobac, who greets me warmly. As he reviews my ecg and echo report, I check him out. He’s a tall, thin, elegant man who looks like he may have run a few marathons himself.

“You’ll never see a fat cardiologist,” my old nurse buddy Laura says. “Yet, there are many neurotic psychiatrists,” she points out. Laura has developed extensive character profiles of every medical specialty. According to her, neurologists are precise and nerdy, gastroenterologists are messy and swear a lot ߝ “think of what they do!” ߝ and all ophthalmologists have small, legible handwriting. Her theories have yet to be tested.

Dr. Drobac introduces himself and we sit down opposite each other for the “functional inquiry,” also known as the “patient interview.”

“How have you been feeling?” he starts off.

“Great! No problem!” I say. “Asymptomatic,” I feel compelled to add.

“Any history of family illnesses?”

“My mother had early onset Parkinson’s disease and manic depression. My father had type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease.”

Died from it, too, but I keep that detail to myself so as not to prejudice my case.

“Do you smoke?”

“Never!” How virtuous am I?

“Take any prescription drugs on a regular basis?

“No.” My body is a temple!

“How about recreational drugs?”

“No . . .” Well, not lately . . .

“What about alcohol?”

“Clearly, not enough.” Now that gets a laugh out of him.

“Are you a Muslim?” he asks, breaking from the script of a standard cardiac history to figure out who I am. He hasn’t quite got me pegged.

“No,” I say. “Jewish. We like to eat. But I plan to start drinking more red wine as soon as possible. In moderation, of course. Strictly for the cardio-protective properties.” Broccoli and dark chocolate, too. From now on, I’m going to do everything right. My mouth is dry, my hands are beginning to shake. “I have a feeling you’re about to give me bad news.”

“No, I’m not.” He smiles. “Not at all.”

Maybe it’s nothing. What am I worried about? I feel perfectly fine. “Any shortness of breath?” he continues.

“No . . . Not really.” Well . . . maybe, a little, now that you mention it.

“Chest pain . . .”

“No, never!”

“What about chest discomfort or tightness, or racing heartbeats?

Have you had any dizziness, light-headedness, coughing, or fainting spells?”

Now that you mention it . . . I swallow the lump in my throat and stifle the harsh, dry cough I’ve had for a few months. Suddenly, I realize it is a cardiac cough. I’d have recognized it in a patient!

“How do you feel after you walk up a flight of stairs?”

“Not great,” I admit. The truth is I haven’t been able to walk up stairs for a few months now. I’ve been avoiding them when possible, and when not, I take them slowly, pushing against the heaviness in my chest, out of breath within moments. Ditto for hills and any inclines, for that matter.

“Do you have much stress at work?”

“Not at all.” My patients do, but not me! But dare I mention that lately I can barely make it to the end of my shifts at the hospital? I am exhausted by lunchtime. “What’s wrong with Tilda lately? She’s always lying down,” I heard a nurse say in the staff lounge the other day. “I’m taking a power nap,” I said, popping up. At the end of my shifts, I’ve been dragging myself home and crashing into bed, not a drop of energy to spare.

“Are you able to do your daily activities at home?”

“Yes,” I say but don’t tell him that I couldn’t rake leaves or shovel snow this past winter and the house is a mess. I move the vacuum cleaner two sweeps and have to sit down to rest. A laundry basket full of folded clothes sits at the bottom of the stairs, too heavy for me to lift and carry to the top.

“How about sexual activity?”

“Absolutely!”

“Sex is very beneficial for heart health,” he explains.

In that case, I’ll have sex every day ߝ twice a day ߝ if necessary! (Note to self: Notify Ivan of this new treatment protocol.)

“What about exercise?”

“I have a gym membership. I’ve done a few aerobics classes . . .”

Yes, I’ve showed up at all those classes with the improbable names like Guts and Butts, Cardio Funk, and Jazzercise. But my workouts have become lame and “half-hearted.” I can’t get my heart rate up above 100 and it takes a long time to recover and return to my resting rate. Oh, and I’ll never bring a water bottle so I can have an excuse to keep stopping for a drink at the fountain to catch my breath.

“Are you keeping up with your peers?”

I haven’t heard that phrase since I was fourteen when I begged my parents for the real Adidas running shoes with three stripes that the cool kids wore, not the cheap North Stars with only two. Of course it was only a fashion statement and status symbol, since I wasn’t doing any running anyway.

Then there is my recent attempt to keep up ߝ literally. It was on a vacation to Nelson, British Columbia, to visit my friend Robyn, during a group hike up a trail on Pulpit Rock, in the foothills of the Kootenay Range, near the Rockies ߝ listed as a “gentle climb” in the guidebook. As I struggled to keep up with the pack, other friends easily strolling along faster, farther, and higher were casting back sympathetic gazes. Robyn stayed behind with me, looking worried.

“I’m taking it slow . . . so I can . . . enjoy . . . the view,” I said as I huffed and puffed, shaky and breathless. I need to make it to the top of this hill, was all I could think as I kept stopping every few feet to clutch my chest, praying I wouldn’t collapse on the way. I’m a wounded buffalo, trying to keep up with the herd. Shoot the beast! Put it out of its misery! We both knew something was wrong but didn’t discuss it. Now I allow myself to know the truth: I could have dropped dead up there on that mountaintop.

Suddenly I realize the real reason that I quit the amateur parent teacher talent show a few months ago. For my audition, I chose “A Cockeyed Optimist” from South Pacific, and mercifully they cut me off after a few bars since I sucked, but I was also too out of breath to finish. Nonetheless, they gave me a one-line solo in a songand- dance number from CATS that required me to leap onto a platform wearing a skin-tight catsuit (what was I thinking?) and belt out, “Can you ride on your broomstick to places far distant?” I couldn’t make it to broomstick. I bowed out, claiming to be too busy for rehearsals.

“So, no symptoms?” Dr. Drobac presses on.

“No.” Only a premonition of doom, which I’m having right about now.

He makes notes in my chart ߝ I now have a chart! ߝ probably jotting down unreliable historian, the damning term for patients who aren’t to be trusted. He’s recorded my symptoms ߝ what the patient reports ߝ and now moves on to the physical examination, the signs ߝ what he, the physician, observes and can measure.

We look at the ecg together. “Mild ventricular hypertrophy,” he notes and points out the deep amplitude spikes in the chest leads and explains that my left ventricle is dangerously enlarged as a result of having to work extra hard to pump blood against the resistance of a constricted aortic valve. Any icu nurse would grasp what he’s talking about, but my thinking is so jumbled I can’t follow his train of thought.

He stands up for the physical examination, ready to discover his own findings. Okay, let the objective tests be the judge. I may lie, but they won’t.

Back in my patient “uniform,” I lie down on the examining table. Dr. Drobac palpates my pulses, the carotid in my neck, brachial in my arm, radial at my wrist, femoral in my groin, popliteal at the back of my knees, and dorsalis in my feet. My pulses have always been weak and he notes that. He examines my jugular neck veins, which reflect the pressures in my heart. He places the bell of his stethoscope on my chest, closes his eyes, and listens. As I await my verdict I recall that according to Laura’s profile, in addition to being slim and fit, cardiologists are the most musical of doctors. It does make sense: they spend their days listening to the melodies of the heart and have to be exquisitely attuned to pitch, volume, rhythm, tempo, crescendos, and diminuendos.

As Dr. Drobac moves his stethoscope around my chest, I know exactly what he hears: a slushy, mushy whooshing. My heart doesn’t have the distinct sounds of a healthy cardiac cycle of contracting and relaxing; not the vigorous lub-dub of strong ventricles pumping effectively with valves opening and closing efficiently. My heart is the swish, swish of a lazy, burbling stream.

As a child, I was invited by medical schools as an interesting case study for doctors-in-training to learn abnormal heart sounds. Any first-year med student who could not correctly diagnose my obvious, loud systolic murmur would surely fail. But, when I grew up and became a nursing student myself, I stayed home from class the day they taught cardiac auscultation. We were supposed to listen to each other’s hearts and my cover would have been blown.

Back in my civvies, I sit down with Dr. Drobac, who looks me squarely in the eyes. “It’s clear why you’ve come to me now. You’re not feeling well, not keeping up. The echo shows that your valve is tight. You have severe aortic stenosis.” He gives me a moment to take that in, then says what I’ve waited all my life not to hear. “There is no doubt in my mind that you need open-heart surgery to replace your valve and to repair part of your aorta, too.”

Valve plus aorta. Cut and blow-dry. Shave and a haircut, two bits. The bottom drops out. I can’t breathe. His words catapult me to the other side. I’ve crash-landed on Planet Patient, a destination where no one ߝ but especially no nurse ߝ wants to go. Hey, don’t I get any immunity from these things happening to me?

Way over there is the doctor, talking to me from the safe side, waving and smiling from the far shore. He still seems to be thinking he’s giving me good news.

“You’ll need a cardiac angiogram first,” he continues, eager to get this party started, “to rule out coronary artery disease before surgery. . . .”

Of course. The cardiac surgeon doesn’t want to open me up and get in there only to find blocked arteries and that I need a coronary artery bypass as well as a valve replacement.

“Can this wait awhile?” I ask.

“Better to face it now, when you’re feeling relatively well, with no other co-morbidities.”

He means high blood pressure, peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery disease, hardening of the arteries, diabetes, kidney failure, a little of this, a touch of that, things waiting in the wings for most of us, one day, eventually.

“Your aorta is enlarged . . . the valve severely constricted . . . blood flow is reduced . . . ejection fraction is less than 30 per cent . . . you’re not getting adequate blood supply.”

“Could it be repaired? A minimally invasive procedure?” Could this have been avoided if I’d dealt with it earlier? That question, I wonder, but don’t dare ask since I don’t want to know the answer.

“No, your valve is too diseased. Extensive work needs to be done. It has to be replaced along with part of the aorta. It can only be fixed by opening the chest.”

But these things happen to patients! “I need time to think about it.”

“Don’t take too long.”

“When should it be done?”

“Soon. Within the next few weeks . . .”

Open-heart surgery ߝ how inconvenient! I had lots of other, much more fun plans for the summer! Taking a break from my work in the icu, spending time with Ivan and the kids, working as a camp nurse, spending time at my brother Tex’s cottage on Georgian Bay. And this was the summer we were finally going to adopt a puppy, a year after the death of our elderly dog, Rambo.

Dr. Drobac asks if I have any questions. None and many, but first I have something to tell him that’s way more urgent than any questions I might have.

“I want you to know that if I get a serious complication and don’t wake up afterward, or if I become severely brain-damaged or have to be on prolonged life support, please let me go. If it’s my time, let me go.” I do not want to be kept around beyond my useful shelf life.

I blurt out these dire directives, not bothering to explain why catastrophe is uppermost on my mind.

He’s incredulous, at a loss as to how to react to my at-the-ready disaster plan. “Have you thought this through?”

Have I ever! I think but can only nod yes to his question.

He looks perplexed, perhaps wondering how to reassure someone so anxious and somewhat irrational-sounding.

“If that’s how you feel,” he says, taking me at my word, “you should document your wishes and make sure to tell your family doctor.”

“I don’t have one.”

“Get a lawyer and write a living will. Spell out your advance directives. Let your family know your wishes for your end-of-life care. Inform the surgeon.” He shakes his head. “I don’t want to disappoint you, but you’re actually going to do very well. I wouldn’t send you for surgery if I didn’t think you were going to make it. This is a routine case.”

Surely he’s had patients who’ve died from “routine” surgery. And yes, I know, it is a good thing to be an ordinary patient with a common problem, but, see, I don’t want to be a patient at all! Walking slowly out of his office into the bright, hot summer afternoon, I’m scared out of my mind. Admittedly, there’s a tiny bit of relief, too, to be set free from this heavy secret buried inside of me all of these years. In my heart of hearts, I knew this day would come. I’ve always felt I was getting away with something, continually dodging a bullet. Up until now, I’ve managed to stay on this side of the bed, a nurse in charge of others’ care. Now I’ll be the one in the bed, nurses bending over my body, tending to me.

I’ve always been such a big champion of our health care system, here in Canada, but will I remain a loyal fan when I’m on the receiving end?

I’m also a writer of stories that have been described as “heartwarming” and “heart-wrenching.” The only thing I know for certain about the story ahead of me is that it will be heart-stopping.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"A smart patient knows more about coping with their disease than their physician, and Tilda Shalof's insights into the rigors of heart surgery are even more provocative since she brings a nurse's wisdom to her own operation."

—Dr. Mehmet Oz, Host of the The Dr. Oz Show

From the Hardcover edition.

—Dr. Mehmet Oz, Host of the The Dr. Oz Show

From the Hardcover edition.