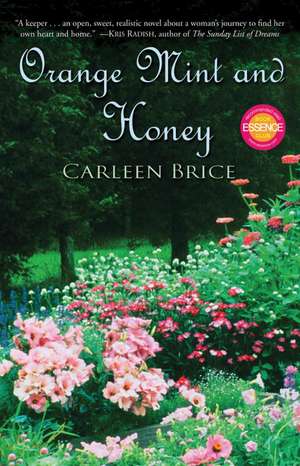

Orange Mint and Honey

Autor Carleen Briceen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2008

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

–Nikki Giovanni, author of Acolytes

Broke and burned-out from grad school, Shay Dixon does the unthinkable after receiving a “vision” from her de facto spiritual adviser, blues singer Nina Simone. She phones Nona, the mother she had all but written off, asking if she can come home for a while.

When Shay was growing up, Nona was either drunk, hungover, or out with her latest low-life guy. So Shay barely recognizes the new Nona, now sober and with a positive outlook on life, a love of gardening, and a toddler named Sunny. Though reconciliation seems a hard proposition for Shay, something unmistakable is taking root inside her, waiting to blossom like the morning glories opening up in Nona’s garden sanctuary.

Soon Shay finds herself facing exciting possibilities and even her first real romantic relationship. But when an unexpected crisis hits, even the wise words and soulful melodies of Nina Simone may not be enough for solace. Shay begins to realize that, like orange mint and honey, sometimes life tastes better when bitter is followed by sweet.

“Carleen Brice has woven her talent for storytelling into a funny, sad, and perceptive novel that speaks to all of us who navigate less-than-perfect relationships with our parents or children.”

–Elyse Singleton, author of This Side of the Sky

“Brice deftly shows the importance and joy of understanding our past and not only forgiving those who hurt us, but loving them in spite of that hurt. Readers of Terry McMillan and Bebe Moore Campbell will find a new writer to watch.”

–Judy Merrill Larsen, author of All the Numbers

Preț: 118.01 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 177

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.59€ • 24.54$ • 18.99£

22.59€ • 24.54$ • 18.99£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 16-22 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345499066

ISBN-10: 0345499069

Pagini: 324

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: ONE WORLD

ISBN-10: 0345499069

Pagini: 324

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: ONE WORLD

Extras

Chapter 1

What Would Nina Simone Do?

i should have known things were getting bad when Nina Simone showed up. Don’t get me wrong. I love Nina. I’ve been listening to her since History of Jazz sophomore year. The professor taught us to worship the great men of jazz, but it was the women who drew me in: Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Dinah Washington, Bessie Smith, Mildred Bailey. They were queens, priestesses, goddesses—encouraging me, pointing me away from danger, schooling me in the ways of life. Especially Nina Simone.

I listened to Nina Simone a thousand times, and I always got something from her music. But the night she came to me for the first time she must have known I needed more than a song could offer. I knew a famous singer—and a dead one at that—shouldn’t have been in my bedroom, but somehow I wasn’t surprised to see her because I had been wishing she were there. Wishing she would tell me what to do.

Usually when I was down I could keep going. But this time I bumped up against something that I couldn’t get over, a wall as hard and cold and impossible to see through as frosted glass. I had lost my job writing grant proposals for an indigent-care clinic, stopped going to class, and received an eviction notice from my landlord. But still all I could do was listen to music, hanging on to the life preserver of Nina Simone’s eerie, regal voice.

That night, I was listening to the fast version of “House of the Rising Sun.” It’s a live recording, seven minutes long. Nina gets so into it, you can’t make out what she’s singing. Behind her, the band chants “rising sun, rising sun” over and over, and the audience claps to the fast beat. The piano, the clapping hands, and the tambourine sound like church and juke joints, like sweat and heat, free and alive. I started dancing. I hadn’t had the energy to get out of my pajamas for a week, but “House of the Rising Sun” had me shaking my head back and forth, twirling in circles, and pumping my arms and legs up and down like I was performing a tribal ritual, like I was one of Alvin Ailey’s dancers. I danced through the song three times until all thoughts of jobs and grad school and unpaid bills were erased from my mind, and I could sleep.

At 3:33 a.m. I opened my eyes and Nina Simone was there, as if I had conjured her, standing in front of my bedroom window, blue moonlight spotlighting her features—thick lips, proud nose, slanted eyes rimmed in kohl like Cleopatra’s. I had been asking myself for days WWNSD (What would Nina Simone do?) and now she had come to tell me. I didn’t know if she was a ghost or a hallucination, and I didn’t care. Eyes wide, heart thumping like the speakers in the car of a teenaged boy, I sat up and waited for Nina Simone to say something wise, to tell me how to fix the mess I’d made of my life, to comfort me, and convince me that I had everything I needed to move forward inside me.

“You’ve really screwed up now,” she said.

“What?”

“You heard me.”

That’s how low I had sunk. Even the spirits of the dead or my own daydreams were turning on me. “I thought you were going to offer me some advice!”

“You’re a grown woman. Why should I tell you what to do?”

It sounded bad when she said it. But I was tired. Tired of always having to figure things out, tired of always having to do everything myself. I’d been taking care of myself since I was eight years old. So for someone else to tell me what to do was exactly what I wanted. For once in my life, I wanted someone else to carry the load. “Because I need help!” I shouted. They were words I had never said before. But then again Nina Simone had never been in my apartment before. It was a night of firsts.

”You got that right,” she said, taking in the mounds of dirty clothes, used Kleenexes, heaps of junk mail, textbooks, CDs, notebooks, and milk-crusted cereal bowls and teacups.

“What I need is . . . is just a break. A rest. A time-out.”

Just the week before, Carl, my advisor, had convinced me that time off was what I needed. Actually, he had “strongly suggested” that I take a year off.

“No!” I had yelled, the most intense emotion I had shown in forever. As exhausted and sick of everything as I was I couldn’t just drop out. I couldn’t be away from school for an entire year.

He stared at me, even more worried.

“I mean, I can’t fall that far behind. I can take a semester off. You’re right, a semester off will do me some good.”

“Okay,” he said, relief washing over his face.

I guess since that MIT student set herself on fire a few years ago—even after visiting the mental health service—the plan was to get depressed college students off campus ASAP. Let them be someone else’s lawsuit in the making.

“What will you do with your time off?”

“I have no idea.” What did people do with time off? I had never taken a day off in my life. If I didn’t have to work, I still had papers to write or tests to study for. Even during the summers I took at least one class or put in extra hours at work. I’d never even skipped school before now. Playing hooky was something that bad kids, going-to-end-up-just-like-their-parents kids did.

“What about your family? Friends? Don’t you have anybody who can help?”

You would think that since I was sitting in front of him in dirty, rumpled clothes and a bandanna on my head, looking like “Who shot John?” as my old hairdresser Belinda used to say, he would know the answer to that question.

Of course, being an academic, he wasn’t much better dressed. Like me, he had on the requisite khakis and button-down shirt. We could have been twins except his clothes probably didn’t come straight out of the hamper. He still thought I was like all his other students, who got care packages, plane tickets, and checks from home. But all I ever got from Nona were postcards from her new, allegedly sober, life. And friends? The last good friend I had was in high school. Stephanie was still back in Denver. I hadn’t spoken to her since we graduated.

“I’ll be fine,” I said.

“I don’t know what’s going on, but you might want to see someone. You know? A professional. I want you to come back ready to finish your thesis.”

My thesis was just one of many things that had stalled. I nodded, exhausted. All I wanted to do was go back home and turn on my music.

“Let’s touch base in a month or so. Send me an e-mail, let me know how you’re doing.”

“I’ll be fine,” I repeated.

Though, clearly, I was far from fine. Things had only gotten worse. I had been “resting” for a week now, and look what happened: A dead woman was sitting in my bedroom talking to me.

“Go home, Shay,” Nina Simone said.

She knew my name.

“You need to go home,” she said.

She must have read my mind, which shouldn’t have been too hard considering there was a good chance she was being generated from the same place. But like Carl, she didn’t understand.

The last time I saw Nona I was in my junior year in college. She came to Iowa City when she reached the step where they make you apologize. She was very pregnant, and I couldn’t believe how ugly she was. Her face was all broken out and she must have gained fifty, sixty pounds. Not just in her breasts and stomach, but in her face, arms, hands, back, butt, and thighs. The bags under her eyes were puffed up like pot stickers. Even her feet were fat.

When I saw her, saw how heavy and zitty she was, I was almost happy she had come. I kept my eyes on her bloated feet the whole time she read her apology. Her voice shook. I don’t remember exactly what she said. Something about being sorry she let me down, sorry I learned I couldn’t trust her. But I remember her saying something about us “being mother and daughter again” and, even though I was looking down at her feet, I saw her rest her hand on her stomach when she said the word mother.

That was too much. Acting like her pregnancy was a good thing, not a horrible, stupid mistake. I had actually been hopeful when she told me she was going to A.A. For the first few months I thought, Wow, she’s really going to do it this time. Stupid me, I actually let myself believe her. Then she got pregnant. Knocked up by a guy she met in A.A., who promptly left her high and dry just like my own father had; and there she was expecting me to believe that things were different. She couldn’t even do A.A. without going off with some guy! She was thirty-six years old and she had never heard of birth control? Never heard of AIDS or chlamydia or herpes?

She told me she hoped I would give her another chance. I think she wanted me to shout “I forgive you!” and throw myself into her arms. But I just stared at her feet, at the flesh rising like bread dough over the straps of her red sandals.

Nina Simone gingerly toed a pair of jeans out of her way, revealing the panties I had worn with them weeks ago tangled up inside, and walked toward me. I hoped she wouldn’t get too close. It had been a while since I had seen soap and water. I was cloaked in a cloud of funk toxic enough to re-kill a dead woman.

She sat on the foot of my bed. “You could rest. Let your mother take care of you.”

I snorted. “That’s not how it worked. I took care of Nona. And I’m done.”

“Maybe it would be different. Maybe you’ve got nothing to lose.”

I doubted it would be very different, but she was right about my having nothing to lose. Spending the next few months in my old VW Bug didn’t sound very appealing. But still I hesitated.

“Go home,” Nina Simone urged, her long earrings swinging like chandeliers.

So I picked up the phone and called Nona for the first time in seven years.

What Would Nina Simone Do?

i should have known things were getting bad when Nina Simone showed up. Don’t get me wrong. I love Nina. I’ve been listening to her since History of Jazz sophomore year. The professor taught us to worship the great men of jazz, but it was the women who drew me in: Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Dinah Washington, Bessie Smith, Mildred Bailey. They were queens, priestesses, goddesses—encouraging me, pointing me away from danger, schooling me in the ways of life. Especially Nina Simone.

I listened to Nina Simone a thousand times, and I always got something from her music. But the night she came to me for the first time she must have known I needed more than a song could offer. I knew a famous singer—and a dead one at that—shouldn’t have been in my bedroom, but somehow I wasn’t surprised to see her because I had been wishing she were there. Wishing she would tell me what to do.

Usually when I was down I could keep going. But this time I bumped up against something that I couldn’t get over, a wall as hard and cold and impossible to see through as frosted glass. I had lost my job writing grant proposals for an indigent-care clinic, stopped going to class, and received an eviction notice from my landlord. But still all I could do was listen to music, hanging on to the life preserver of Nina Simone’s eerie, regal voice.

That night, I was listening to the fast version of “House of the Rising Sun.” It’s a live recording, seven minutes long. Nina gets so into it, you can’t make out what she’s singing. Behind her, the band chants “rising sun, rising sun” over and over, and the audience claps to the fast beat. The piano, the clapping hands, and the tambourine sound like church and juke joints, like sweat and heat, free and alive. I started dancing. I hadn’t had the energy to get out of my pajamas for a week, but “House of the Rising Sun” had me shaking my head back and forth, twirling in circles, and pumping my arms and legs up and down like I was performing a tribal ritual, like I was one of Alvin Ailey’s dancers. I danced through the song three times until all thoughts of jobs and grad school and unpaid bills were erased from my mind, and I could sleep.

At 3:33 a.m. I opened my eyes and Nina Simone was there, as if I had conjured her, standing in front of my bedroom window, blue moonlight spotlighting her features—thick lips, proud nose, slanted eyes rimmed in kohl like Cleopatra’s. I had been asking myself for days WWNSD (What would Nina Simone do?) and now she had come to tell me. I didn’t know if she was a ghost or a hallucination, and I didn’t care. Eyes wide, heart thumping like the speakers in the car of a teenaged boy, I sat up and waited for Nina Simone to say something wise, to tell me how to fix the mess I’d made of my life, to comfort me, and convince me that I had everything I needed to move forward inside me.

“You’ve really screwed up now,” she said.

“What?”

“You heard me.”

That’s how low I had sunk. Even the spirits of the dead or my own daydreams were turning on me. “I thought you were going to offer me some advice!”

“You’re a grown woman. Why should I tell you what to do?”

It sounded bad when she said it. But I was tired. Tired of always having to figure things out, tired of always having to do everything myself. I’d been taking care of myself since I was eight years old. So for someone else to tell me what to do was exactly what I wanted. For once in my life, I wanted someone else to carry the load. “Because I need help!” I shouted. They were words I had never said before. But then again Nina Simone had never been in my apartment before. It was a night of firsts.

”You got that right,” she said, taking in the mounds of dirty clothes, used Kleenexes, heaps of junk mail, textbooks, CDs, notebooks, and milk-crusted cereal bowls and teacups.

“What I need is . . . is just a break. A rest. A time-out.”

Just the week before, Carl, my advisor, had convinced me that time off was what I needed. Actually, he had “strongly suggested” that I take a year off.

“No!” I had yelled, the most intense emotion I had shown in forever. As exhausted and sick of everything as I was I couldn’t just drop out. I couldn’t be away from school for an entire year.

He stared at me, even more worried.

“I mean, I can’t fall that far behind. I can take a semester off. You’re right, a semester off will do me some good.”

“Okay,” he said, relief washing over his face.

I guess since that MIT student set herself on fire a few years ago—even after visiting the mental health service—the plan was to get depressed college students off campus ASAP. Let them be someone else’s lawsuit in the making.

“What will you do with your time off?”

“I have no idea.” What did people do with time off? I had never taken a day off in my life. If I didn’t have to work, I still had papers to write or tests to study for. Even during the summers I took at least one class or put in extra hours at work. I’d never even skipped school before now. Playing hooky was something that bad kids, going-to-end-up-just-like-their-parents kids did.

“What about your family? Friends? Don’t you have anybody who can help?”

You would think that since I was sitting in front of him in dirty, rumpled clothes and a bandanna on my head, looking like “Who shot John?” as my old hairdresser Belinda used to say, he would know the answer to that question.

Of course, being an academic, he wasn’t much better dressed. Like me, he had on the requisite khakis and button-down shirt. We could have been twins except his clothes probably didn’t come straight out of the hamper. He still thought I was like all his other students, who got care packages, plane tickets, and checks from home. But all I ever got from Nona were postcards from her new, allegedly sober, life. And friends? The last good friend I had was in high school. Stephanie was still back in Denver. I hadn’t spoken to her since we graduated.

“I’ll be fine,” I said.

“I don’t know what’s going on, but you might want to see someone. You know? A professional. I want you to come back ready to finish your thesis.”

My thesis was just one of many things that had stalled. I nodded, exhausted. All I wanted to do was go back home and turn on my music.

“Let’s touch base in a month or so. Send me an e-mail, let me know how you’re doing.”

“I’ll be fine,” I repeated.

Though, clearly, I was far from fine. Things had only gotten worse. I had been “resting” for a week now, and look what happened: A dead woman was sitting in my bedroom talking to me.

“Go home, Shay,” Nina Simone said.

She knew my name.

“You need to go home,” she said.

She must have read my mind, which shouldn’t have been too hard considering there was a good chance she was being generated from the same place. But like Carl, she didn’t understand.

The last time I saw Nona I was in my junior year in college. She came to Iowa City when she reached the step where they make you apologize. She was very pregnant, and I couldn’t believe how ugly she was. Her face was all broken out and she must have gained fifty, sixty pounds. Not just in her breasts and stomach, but in her face, arms, hands, back, butt, and thighs. The bags under her eyes were puffed up like pot stickers. Even her feet were fat.

When I saw her, saw how heavy and zitty she was, I was almost happy she had come. I kept my eyes on her bloated feet the whole time she read her apology. Her voice shook. I don’t remember exactly what she said. Something about being sorry she let me down, sorry I learned I couldn’t trust her. But I remember her saying something about us “being mother and daughter again” and, even though I was looking down at her feet, I saw her rest her hand on her stomach when she said the word mother.

That was too much. Acting like her pregnancy was a good thing, not a horrible, stupid mistake. I had actually been hopeful when she told me she was going to A.A. For the first few months I thought, Wow, she’s really going to do it this time. Stupid me, I actually let myself believe her. Then she got pregnant. Knocked up by a guy she met in A.A., who promptly left her high and dry just like my own father had; and there she was expecting me to believe that things were different. She couldn’t even do A.A. without going off with some guy! She was thirty-six years old and she had never heard of birth control? Never heard of AIDS or chlamydia or herpes?

She told me she hoped I would give her another chance. I think she wanted me to shout “I forgive you!” and throw myself into her arms. But I just stared at her feet, at the flesh rising like bread dough over the straps of her red sandals.

Nina Simone gingerly toed a pair of jeans out of her way, revealing the panties I had worn with them weeks ago tangled up inside, and walked toward me. I hoped she wouldn’t get too close. It had been a while since I had seen soap and water. I was cloaked in a cloud of funk toxic enough to re-kill a dead woman.

She sat on the foot of my bed. “You could rest. Let your mother take care of you.”

I snorted. “That’s not how it worked. I took care of Nona. And I’m done.”

“Maybe it would be different. Maybe you’ve got nothing to lose.”

I doubted it would be very different, but she was right about my having nothing to lose. Spending the next few months in my old VW Bug didn’t sound very appealing. But still I hesitated.

“Go home,” Nina Simone urged, her long earrings swinging like chandeliers.

So I picked up the phone and called Nona for the first time in seven years.

Descriere

This haunting, exquisitely written story about mothers and daughters and the power of healing and forgiveness marks the stunning debut of a new novelist.

Notă biografică

Carleen Brice was named 2008 “Breakout Author of the Year” by The African American Literary Awards Show for her debut novel, Orange Mint and Honey, which was also an Essence Book Club selection. Brice is also the author of Walk Tall: Affirmations for People of Color, and Lead Me Home: An African American’s Guide Through the Grief Journey. She edited the anthology Age Ain’t Nothing but a Number: Black Women Explore Midlife. She lives in Denver, Colorado, with her husband and two cats.