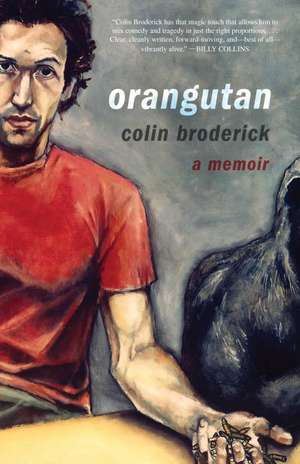

Orangutan: A Memoir

Autor Colin Brodericken Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 noi 2009

Orangutan is the story of a generation of young men and women in search of identity in a foreign land, both in love with and at odds with the country they've made their home. So much more than just another memoir about battling addiction, Orangutan is an odyssey across the unforgiving terrain of 1980s, '90s, and post-9/11 America.

Whether he is languishing in the boozy squalor of the Bronx, coke-fueled and manic in the streets of Manhattan, chasing Hunter S. Thompson's American Dream from San Francisco to the desert, or turning the South into his beer-soaked playground, Broderick plainly and unflinchingly charts what it means to be Irish in America, and how the grips of heritage can destroy a man's soul. But brutal though Orangutan may be, it is ultimately a story of hope and redemption—it is the story of an Irish drunk unlike any you've met before.

Preț: 123.09 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 185

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.56€ • 24.45$ • 19.64£

23.56€ • 24.45$ • 19.64£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307453402

ISBN-10: 0307453405

Pagini: 340

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 0307453405

Pagini: 340

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

COLIN BRODERICK was raised Irish Catholic in the heart of Northern Ireland. In 1988, at the age of twenty, he moved to the Bronx to drink, work construction, and pursue his dream of becoming a writer. For the next twenty years, as he drank himself into oblivion: there were failed marriages, car wrecks, hospitals and jail cells. Few people who have been a slave to an addiction as vicious, destructive, and unrelenting as Broderick's have lived to tell their tale. Orangutan is the story of an Irish drunk unlike any you've met before. Broderick has written a play, Father Who, and published articles in The Irish Echo, The Irish Voice, and The New York Times.

Recenzii

"Colin Broderick has that magic touch that allows him to mix comedy and tragedy in just the right proportions…Clear, cleanly written, forward-moving, and—best of all—vibrantly alive."

—Billy Collins

"I have great admiration for the style and the tenacity and the sheer swerve of Colin Broderick's work. He is one of those younger writers who makes sense of where we are right now. He has his finger on the collective pulse."

—Colum McCann

"Colin Broderick has written a book that is not of the "I was lost & now I am found" genre. It is his unique story of drugs drink dregs & degradation uniquely told and devoid of self pity or any attempt to justify his loony behaviour. Broderick does not preach. He merely says as they did in the old west "Ah wouldn' t do dat if I was you." Read the mans book and it might save a life which might be your own"

—Malachy McCourt

"His book is part grail quest, part cautionary tale and part rollicking Irish emigrant’s adventure story. What makes it remarkable is that he manages to snatch a victory out of near impossible odds. This book is written in blood, it deserves to become a classic."

—Irish Voice

"Readers who appreciate the gritty style of Charles Bukowski or are fans of Augusten Burroughs’s Dry will find this work enveloping."

—Library Journal

"It is honest, moving and at times heart-wrenching. Orangutan is, at its core, a story of a man who spent two decades fighting the beast inside of him and surviving life as he did so."

—Irish America magazine

"...to my delight, Broderick has all the storytelling abilities the Irish people have become known for around the world and in almost every culture."

—Irish Focus

"As a writer, he's a bit like the driver of one of those illegal taxis, taking you at high speed to some very dark places."

—Minneapolis Star Tribune

—Billy Collins

"I have great admiration for the style and the tenacity and the sheer swerve of Colin Broderick's work. He is one of those younger writers who makes sense of where we are right now. He has his finger on the collective pulse."

—Colum McCann

"Colin Broderick has written a book that is not of the "I was lost & now I am found" genre. It is his unique story of drugs drink dregs & degradation uniquely told and devoid of self pity or any attempt to justify his loony behaviour. Broderick does not preach. He merely says as they did in the old west "Ah wouldn' t do dat if I was you." Read the mans book and it might save a life which might be your own"

—Malachy McCourt

"His book is part grail quest, part cautionary tale and part rollicking Irish emigrant’s adventure story. What makes it remarkable is that he manages to snatch a victory out of near impossible odds. This book is written in blood, it deserves to become a classic."

—Irish Voice

"Readers who appreciate the gritty style of Charles Bukowski or are fans of Augusten Burroughs’s Dry will find this work enveloping."

—Library Journal

"It is honest, moving and at times heart-wrenching. Orangutan is, at its core, a story of a man who spent two decades fighting the beast inside of him and surviving life as he did so."

—Irish America magazine

"...to my delight, Broderick has all the storytelling abilities the Irish people have become known for around the world and in almost every culture."

—Irish Focus

"As a writer, he's a bit like the driver of one of those illegal taxis, taking you at high speed to some very dark places."

—Minneapolis Star Tribune

Extras

My wife reads my journal and is waiting for me when I come home from work with it opened to the page where I say that I have fallen helplessly in love with a teenager. The same teenager she’s had her suspicions about all along. I try to deny it, but she informs me that it’s too late, my good buddy Bill, my business partner, my AA sponsor, has already confirmed that it’s true. I take a seat and try to comprehend the magnitude of his deceit.

I decide to take this opportunity to I tell her how I really feel. I tell her that I’m unhappy in the marriage and that I want a divorce. She hopes I rot in hell. So I move to the couch in the basement.

Within a week Bill and I have parted company. He has apologized for his indiscretion but I can’t look at him anymore without wanting to rip out his throat. He comes by when I’m not there and takes his few personal items, then has me served with papers seeking half the business. I tear up the papers and throw them in the trash can. I have never seen him or spoken to him since.

The adoption agency has called; they have a child for us in South America. She’s almost two years old. We are to fly immediately to meet her and take her back to the States. Brigitte tells me that this is the last thing she wants me to do for her. She cannot do it alone. The agency wouldn’t allow it. She needs a husband. I agree to go along.

We agree that when I come back I will find an apartment somewhere nearby and we will work something out so that we can take care of the child together.

Three days before we fly to Ecuador I find out that Brigitte has emptied my bank accounts, sold the stocks I had purchased, and maxed the credit cards that were in my name. I’m suddenly about forty thousand dollars in the hole. I am completely broke. I have to call Tony to borrow money for gas. She won’t lend me twenty dollars of my own money. My friend who’s a lawyer begs me not to go through with the adoption process. He tells me that I’ll lose everything. I know he’s right, but I feel guilty about falling in love with someone else, so I go along as a form of penance.

My friend steps in and takes care of the business while I’m gone. The poet Rick Pernod and I decide to become business partners and make a fresh go of it at the café. I tell Oksana that I am in love with her, and she tells me she will be waiting for me when I return from Ecuador. Brigitte and I travel to Ecuador. My daughter is a beautiful, healthy two-year-old, and I cry the moment I take her in my arms. I had never expected to fall in love with her instantaneously. She is the most beautiful child I have ever seen in my entire life. I look into her eyes and I know her and she knows me. I return from Ecuador a few days early, as agreed, to set up my own apartment and prepare for my daughter’s return. Oksana and Rick are waiting for me at the airport. I am an emotional basket case.

I borrow money from Tony and rent a one-bedroom apartment in Riverdale, up on the Parkway. I buy a new bed and move a few personal items out of the house. Brigitte returns from Ecuador with our daughter. She refuses to let me see her, just as my lawyer had predicted. She hires an expensive lawyer of her own and announces she wants full custody. After a brief struggle and the advice of two other attorneys, I relent. I give her everything. The house, the money, Molly, and our daughter. She moves away and I have not seen or heard from her since.

I have an apartment in Riverdale that I can’t afford. I have a ten-year-old car in need of repair. I’m completely broke. My credit is destroyed. The coffee shop is barely paying its own bills.

I close the café on a Friday night after I have signed the divorce papers. I lock the doors. Oksana has gone out for the night with some friends of hers. I am alone. I turn down the lights and take out a bottle of absinthe someone sent Rick and me as a gift from Prague. It’s the real deal. The illegal stuff with the wormwood. We were saving it for special customers. I pour a small glass of it. I dip a spoonful of sugar into it, remove it again and then light the absinthe-soaked sugar. It burns with a blue-green flame. I haven’t tasted alcohol in eight years. I will have one drink just to see what it tastes like. I want to drink again. I don’t want to be a drunk. I’ve just decided that I’m going to have a few drinks every once in a while. I deserve it after all I’ve been through. The flame is hypnotic. As it dances I picture van Gogh in Arles, Joyce in Paris, Hemingway in Spain. I was meant to drink. Why should I deny myself this right? I was born to drink. I drop the spoon into the glass and stir. I take it in my fist and smell its sharp menthol fumes. I lift the glass and my arm almost doesn’t want to bend. I force it. It hits my lips and I don’t stop until the glass is empty. My eyes water. I set the glass down and brace myself. My throat burns. A hot flame runs all the way to my gut. I’m still alive. That tasted good. I think I’ll have one more. Just one. After three I decide I’d better just take the bottle home with me. I don’t want to get drunk and then have to drive home. I take the scenic route home through Fieldston. There’s something familiar about myself that I can’t quite put my finger on, but I like it. I go home and finish the entire bottle. I’m thirty-one years old. I’m broke. I’m divorced for the second time. I have a teenage girlfriend. I’m drinking again.

IT’S DRINKING AGAIN

See, I’m not an alcoholic. I just drank a bottle of absinthe and I’m fine. You people are crazy. Alcoholic! Ha. Jesus, it’s nice to be drinking again. I’m Irish; I’m a writer; who the fuck did I think I was kidding? So I was young and a little confused. Quitting drinking at the age of twenty-three! I can’t believe I have denied myself this pleasure for eight whole years. Never again! I will never put myself through the misery of being sober ever again. Sober life sucks ass. It’s no wonder all my cousins stopped inviting me to their little parties. What a bore I was. And those muscle cramps in my gut, gone. Gone. They were stress-related. I was all bunched up. I was a tightwad miserable fuck. All I needed was a good drink to relax. My God, I feel like an idiot. How? How could I have been so stupid? AA! Jesus. What a bunch of dry old farts. What a miserable, despicable collection of rejects. What a sad, pathetic little family of losers. What they need is a good drink. Every last one of them. I cannot believe I associated myself with those people for eight whole years. My family must have thought I’d lost my mind. I can’t wait to have a few drinks with the lads again. Or a nice bottle of beer with the old man next time I’m home. Jesus, I can’t wait. Drink like a grown-up. You know what? I’m glad I went to AA. I’m glad I went through a couple of therapists. It was not a complete waste. At least now I know myself. I will always be able to monitor my own drinking. If my drinking begins to cause problems, I’ll check myself. I just have to keep an eye on it. If it gets out of hand, if I find myself crossing any lines, I’ll just pull it together, knock it on the head for a week or two. God knows that shouldn’t be a problem. I didn’t drink for eight years. A week or two is a joke. If I watch it, if I’m careful, I’ll be able to enjoy this luxury for the rest of my life. I am so damned happy I could cry. Thank you, God, for giving me this beautiful opportunity to drink again. I promise you I will continue to pray. I will keep the twelve steps in mind and continue to live a good, responsible life. All I have to do is keep my drinking under control. It’s that simple.

TWO WEEKS LATER

It was one in the morning on a hot Friday night. I was sitting in the dark by the open window, watching the traffic roll by on the Henry Hudson Parkway. There’s something about the sound of passing traffic that normally soothes me, but it just wasn’t working on this particular night. Nothing was working. I’d finished the two bottles of wine and started in on the vodka. Oksana was gone. We’d had one of those boozed-up fights the previous night that makes Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? look like a children’s fairy tale. She had stormed out, saying she was going back to live at home with her parents. Again. I was glad she was gone. I needed time to think. Everything was happening so fast I could barely keep up with it all. I was just out of a six-year marriage. My café-bookstore was closing. I was broke and back working construction. I needed a smoke. A nice fat joint would sort me right out. That had always worked before. I’d just go get myself a nice little dime bag of weed. Just enough to take the edge off. I’d come home, turn the lights down, listen to some Floyd. Chill the fuck out. Just like the old days. I’d just have another little glass of vodka for the road. God, it was good to be drinking again.

I took a ride in my old Honda Civic to White Plains Road. The same area where I’d been beaten and left for dead ten years before. It was time to give it another shot. Surely it was more civilized now.

I spotted a few guys hanging out near the old street corner. They looked cool. I was good at this. I have a real feel for people. I can sense danger a mile away. One of the guys, a young black kid, gave me the nod. I nodded back. I was in business. He flipped his head left to right a couple of times, checking for cops, and waved me onto the side street. I made the turn and pulled in at a hydrant. I left the car running and stepped out to greet him as he walked toward me.

I leaned against the front fender and folded my arms nonchalantly. I wanted him to know that I was cool, that we were the same, he and I. We were both cut from the same cloth. I’d done a little dealing myself back in the day, in London. I knew the scene: a lot of posturing, head-nodding, grunting, toughguy shit. I could almost taste the weed already. Eight years without a smoke. This was going to be great. The kid was moving toward me, crossing the street at a brisk pace. And now that I could see him up close, he looked a little crazed. Maybe I’d misjudged this motherfucker. I’d had a lot to drink. It was too late anyway. I was just going to have to roll with it and hope for the best. Maybe I shouldn’t have pulled onto this side street. Maybe I shouldn’t have gotten out of my car. Maybe I shouldn’t have left my apartment. Maybe . . . He had a knife in his hand. He must have pulled it from his waistband. I definitely didn’t see that coming. Fuck.

“Give me your wallet, muthafucka.” He had stopped about an arm’s length away and he held the knife toward me. It was a big knife. Shiny. “Give me your muthafuckin’ wallet, asshole.”

“Fuck you,” my mouth said.

“What d’you say to me, mutherfucker? You wanna die? Give me the muthafuckin’ wallet.”

“Go fuck yourself.” There it was again. That mouth of mine sure did have a life of its own. He swiped the knife across my middle. I managed to pull back just a fraction without making a big to-do about it. He’d missed. Maybe he meant to miss.

“Give me the wallet, man,” he continued. He looked a little perplexed now, as if this was just way too much work. He was obviously used to a little more cooperation than this. “You want to die?” he said.

“You’re not getting my fucking wallet, asshole,” my mouth said with great confidence. He swiped again. This time he was pissed. He slashed the knife across my throat in a wild swing.

“Give me the wallet!” he shouted. “You want to die here?” I casually reached my left hand to my neck and rubbed my fingers across my throat. I held my hand up to my face and looked at the thin streak of blood across my fingers. He’d cut me alright, but barely. It was only a nick across my Adam’s apple. No big deal. He really was pushing it, this kid.

“OK. I’ll tell you what I’m going to do,” I said, pausing to collect myself. It was time for some diplomacy here. This was beginning to get serious. I was going to have to calm down and negotiate. Treat him like a businessman. That’s it. Give the guy a little respect. They love a little negotiation, these guys. They want to feel like they’re being heard. That’s cool. I could roll with that. “I’m going to take my wallet out and I’m going to hand you the cash. But I keep the wallet—” Slash. There he was with that knife again. This time he connected. I lifted my right arm and sure enough there was a huge gash running across my arm between my elbow and my hand. It was wide open. I could see a white wall of flesh. It was deep. This kid was a tough negotiator, no doubt about it. I actually laughed a little. He’d really taken me by surprise with that one. It was time to wrap this thing up before things got out of hand.

“OK,” I said, holding my arm up so that he could get a good look at the cut. “If you put that knife near me one more time, I’m going to take it off you and shove it up your fucking ass.”

“Are you fuckin’ crazy, man . . .”

“I’m going to take my wallet out and give you the cash,” I said, reaching for my wallet. “I’m going to give you the cash and I’m going to keep the wallet.” I had the wallet out. I opened it and he waited, shifting nervously from foot to foot while I removed the cash. There was maybe two hundred dollars in there.

I handed it to him. “Now go fuck yourself, asshole.” He grabbed the cash from my hand and ran off up the side street. When he was about twenty feet away he turned and shouted, “You’re fuckin’ crazy, man. You need fuckin’ help.”

“Fuck you, tough guy,” I shouted after him. It was then that I noticed that a few guys had gathered across the street. They made their way toward me. I was in no hurry to go anywhere at this point. I put my wallet back in my pocket as they gathered around. There were maybe four or five of them. Young black kids.

“He cut you, man?” one of them asked.

I held up my arm so that they could see.

“Fuck, man,” he said, taking a good look at it. “He fucked you up pretty good, huh?”

“Yeah, he’s a real tough guy. He a friend of yours?”

“Naw, man,” one of the other kids said. “We don’t know that guy.” They were all huddled around, inspecting my arm. It did look pretty bad. I felt alright about it somehow. It didn’t hurt too badly.

“Any of you guys got a smoke I could bum?” I asked. A couple of them dug into their pockets. One of them handed me a smoke, another held out a light for me. “Well, guys, it’s been real, but I gotta get myself to a hospital.”

I got back in the Honda and searched around until I found a plastic bag on the passenger-side floor and placed it behind the stick shift between the two seats to catch the blood from my arm. The guys gathered around the car and watched me as I placed it just right. “This muthafucka’s crazy,” one of the kids said, laughing.

I was going to have to find a new spot for weed, I decided. White Plains Road was now officially off-limits.

At the hospital I gave them a false name and told the doctor I’d cut myself cooking a chicken. He eyed me with a look of tired skepticism, jotted something on his clipboard, and sauntered off out of the room, scratching his head without another word, leaving the nurse to patch me up. Apparently he’d heard that one before. He didn’t want to hear the truth any more than I wanted to tell it. I’d had enough fun for one night without having to deal with the cops as well.

Two hours and fifteen stitches later I was back home on my couch with a large tumbler of vodka. The sun was coming up as I finally hit bed. I had to drink half the bottle to put me to sleep. The birds were already chirping in the trees outside my window.

“You’re an asshole,” they were singing cheerfully. “You’re a big fat waste of space,” another one squawked. I got up and closed the curtains on them, fuckin’ birds. What the fuck did they know? Goddamned pain-in-the-ass chirping motherfuckers. Go bug somebody else. Tomorrow was going to be a long day.

When I showed Oksana the stitched gash on my arm the next day, she slapped my face and burst into tears. I guess I deserved it. The blood had caked and blackened around the stitches, making it look a lot worse than it was. I told her an edited version of the story, minimizing my role in the whole scenario as much as possible. I told her that the guy had grabbed my arm through the open window and cut me when I tried to hand him my cash. It didn’t help things much.

I poured us a couple of large glasses of red wine and promised her nothing like that would ever happen again. That did the trick. I was just going to have to be more careful from now on.

I was glad that something so violent had happened so soon. It had really opened my eyes to the dangers involved in drinking again. I could now see clearly where I had crossed the line. I should never have gotten into the car in the first place. I should have just gone to bed. It was a stupid mistake, but there was no point in getting my pants in a bunch about it.

It just wouldn’t happen again. I was sure of it. I had to be careful. I had to keep this beautiful gift of drinking in my life. There was no way I was going back to those goddamned church basement meetings. No siree. I was done with that chapter, thank you very much.

Alcoholics Anonymous! Ha. Who could have ever dreamed up such an outfit? An American, of course. Bill W. What a wanker. Typical: an armchair philosopher; a lazy, good-fornothing couch bum who couldn’t do it by himself. He couldn’t just tighten up a wee bit. Pull up his bootstraps and get on with his life like an Irishman. He couldn’t just cut back a bit when things got out of hand with his drinking. No, no, of course not. That would take effort, self-control, discipline. It might mean work. God forbid. Talk about your stereotypical Yank. If the work was in the bed they’d sleep on the floor. Work? Not on your nelly. Not in this country. But if you’d like to sit down and have a chat about it, well, then, that was a different thing entirely. They’d be lined up around the block for that alright, in deck chairs, of course, with the portable TV and a cooler of refreshments, just in case. Oh, no, old Bill couldn’t just stop; instead he had to dream up some little egomaniacal, cockamamie cult to absolve himself of all his drinking sins and spoil it for everybody else. Well, fuck you, Bill W. Why couldn’t you have kept your big yapper shut? I will never, I repeat: never, associate myself with that bunch of brainwashed buffoons ever again. Not so long as there’s a breath in my body. My poor family. I can’t imagine the embarrassment I must have caused them. “Oh, our boy Colin’s had to get help with his drinking. He’s an alcoholic.” The shame. What utter humiliation. My God. Brainwashed. That’s what I was. Brainwashed. There was no other logical explanation. Keep coming back. It works if you work it. Keep it simple, stupid. Oh, yeah, well I’ve got a slogan for you pal. Go fuck yourself. Boy, was it good to be drinking again.

Things were good between Oksana and me again in no time. She liked the idea that I had been stabbed, that I had a scar. It was her scar. She owned it the way she owned everything about me. I was hers and she was mine.

I was working construction again, but it was different from before. I was a finish carpenter now. I was moving up in the work chain. The work was cleaner and the cash was much better. I was working with a crew of guys installing baseboard and door trim on a job up in Westchester. We had about four hundred apartments to do. It was easy work once you got the hang of it. We worked in crews of two. One guy did the measuring and nailing and the other took care of the cuts. We now had laborers to handle all of the rough stuff. My days of lugging sheets of plywood and floor-sanding machines up and down flights of stairs were over. I left work in the evening as clean as the moment I walked through the door that morning. Now, this was the life.

On Friday evenings the tool belts were discarded and the gang box was bolted shut a good half hour early. Once we had those checks in our hands we were history. Irish lads working in every corner of the city were on the move and their destination was Woodlawn. It was a race straight to the Tara Hill Bar on Katonah Avenue to cash those checks. By five o’clock the place would be jumping, AC/DC on the jukebox, a line of quarters backed up on the pool table, a cold beer in every fist, the occasional group of cheeky-faced Irish American girls stopping by to flirt with the boys. The lads still in their work clothes, dusty from the day, some tanned from a day’s sweat in the sun, tying one on before we all went our separate ways for the weekend. I was back. No, I wasn’t back; I had never been here before. It had never been this good. I was no longer a newbie, fresh-faced and green off the boat. I had survived in this town for twelve years now, while others had chickened out, gone home, or gone mad. That was an accomplishment in itself. This was living. Beer had never tasted so good as it did on those evenings. We had earned it. We had suffered through the hangovers early in the week and managed to bash out another five days’ work. We were the men. You couldn’t take it away from us. We deserved this. For a fleeting crystallized moment, as those first few crisp beers rushed to our heads, we were the kings of Katonah Avenue.

I would usually stay for only about five or six bottles before I said my good-byes. I lived in Riverdale, another fifteen-minute drive away. I had to be careful. I couldn’t afford to get caught drunk driving. I needed my transportation for work. I’d heard enough horror stories over the years that I did go to meetings to know that drunk driving was something I would never do.

On my way home I would stop at the liquor store. Oksana was too young to go to a bar, so I would stock up enough booze and movie rentals to keep us going for the weekend and we’d just hole up for two days until it was time for me to go back to work. A half-gallon of good vodka, one decent bottle of red wine, two magnums of cheaper wine, and a twelve-pack of beer for Sunday to taper off. Who had it better than me? Nobody. I got a letter in the mail about that time from a New York journal called Rattapallax. They wanted to publish one of my short stories. I’d written it just after I’d started drinking again, a response to the Omagh bombing. Rick Pernod had edited the story for me and in the process had taught me a few valuable lessons about the importance of clarity in my work. He’d made only a few suggestions, but those small changes had transformed the story into a fairly tight piece. I’d always been careless in this regard. Every time I’d submitted something before, I’d sent off the rough draft, convinced that whoever was lucky enough to receive my masterpiece would be on the phone in a flash with a book offer and a fat check. Strangely, that had never happened.

I called the editor of the journal and he told me in a voice as mean as a rusty bucket of nails that I should stop by to see him. The editor’s name was George Dickerson. Dickerson was not only a poet and editor, but he was also an actor, best known for his role as the detective in the David Lynch movie Blue Velvet. I told him I would be there within the hour. I was more than a little keen to hear what he had to say.

The man who opened the door of his fifth-floor walkup an hour later looked like something that had been peeled off the blacktop in the parking lot of a truck stop outside of Nevada. A mottled strip of parchment, infused with the tire tracks of an unforgiving life, pockmarks and windburn, oil stains and all. I could not have dreamed of a more suitable candidate to publish

my first short story. I wanted to take him in my arms and hug the life out of the old bastard, but under the circumstances I thought it would be best to resist the temptation.

The apartment might best be described as a den, the den of some curious word-foraging animal. It was a chaotic explosion of paper. There were books and stacks of paper covering every square inch of the place. Sheaves of paper and dusty folders spilled out of every crevice. There wasn’t a square inch of the floor still visible. George made no attempt to excuse the carnage or clear a seat for me. He quite simply slumped into it, and with a nod of his head invited me to do the same.

“So you’re the new Irish writer, huh?” he said as he leaned over and miraculously located, among the madness, the very file that contained my story. I was tempted to suggest that he spray paint it bright orange so that it would be next to impossible to lose in here, but it seemed George understood this chaos better than I was giving him credit for.

“Yeah, that would be me.”

“From the North by the sounds of this story,” he said, flipping through the first few pages. The story was called “Bang.” It is set in the area where I grew up in County Tyrone and narrated in the voice of an elderly farmer. It had been the easiest short story I had ever written; I had bashed it out in two sittings. The voice of the farmer spoke to me and I just put his words on the page. It was that simple. It was an experience that taught me to get out of my own way and let the writing happen. All my previous efforts and struggles with my egotistical sense of how things should sound had availed me nothing. I wasn’t that important, it seemed, in the grand scheme of things.

“I’m from a place called Altamuskin,” I told him. “That’s where the story is set. All those events were part of my own experience of growing up there.”

“Some childhood. You ever think of writing a book about it?”

“I’ve thought about it.”

“By the looks of this story there’s probably enough material there for a couple of books.”

“I want to make sure I can really write before I tackle that stuff. Writing about home is tricky business.”

“You’ll get there.”

Then he started in about his own stuff. He was working on a book of poetry. He was reaching for another folder to show me something he was working on. That’s where he lost me. We’re a selfish breed of creature, writers are. I could have yapped away all day when it was my own writing we were talking about, but the minute he mentioned his stuff I was out the door. I thanked him for the honor of being published in his journal and I was gone.

About a month later, I walked into a magazine store between Seventy-first and Seventy-second on Broadway, and there on the shelf next to Poetry and the Paris Review was the third edition of Rattapallax. I was tempted to announce my good fortune to the other folks in the store browsing through the magazines, but I restrained myself. A gentleman in a tweed jacket and the tussled hair of an English professor lifted a copy and thumbed through it right next to me. Then he returned it to the shelf and bought the Antioch Review instead. There were three copies left on the stand. I bought all three. I would send a copy to my parents and give the others to friends. There may be other stories and journals in my future, but none will ever equal the rush of seeing that first one in print, in a store, for sale, in New York City. I felt like my entire existence had been validated in that one simple moment. I was now a published writer.

Inspired by my newfound success, I started on a new novel. It was time to take this thing seriously. Maybe if I put as much effort into my writing as I did into my drinking, I might actually get somewhere. But it was impossible. I was too tired from working during the day to put the required energy into it. Even when I pushed myself to stay with it, there was always the drink to slow me up. Or Oksana. I discovered quickly that dating an eighteen-year-old could be a real drain on the creative process. Teenagers are a particularly selfish breed of creature; they are like writers in that regard. I’d work on the novel religiously for four days in a row, get drunk for three days, die with a hangover for two days, and then by the time I was feeling like writing again I was ready for another drink. After six months I had amassed a sketchy seventy pages. The more I looked at it, the uglier it got. The uglier it got, the more I drank. I needed some fresh experience, some inspiration.

Every summer, Oksana took a trip to Russia to visit her grandparents. This year I was invited to tag along to meet the rest of the family. I leapt at the chance.

Since we had started seeing each other, Oksana had been bringing me all her own favorites to read: Turgenev, Dostoyevsky, and Chekhov. I was drunk with the tragedy of it all: unrequited love, duels to the death—they really knew how to wipe the smile off your face in a hurry, these Ruskies. We spent months reading entire books aloud to one another: Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time, Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita; her favorite, Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, we read twice.

Oksana went a couple of weeks ahead of me to spend the whole summer in Russia, as she always did. I had time for only three weeks.

I traveled with her mother. We had a pleasant, civilized flight, drinking tea and chatting, reading the New Yorker. The thought crossed my mind more than once that this might have been a more enjoyable trip with someone of my own age, someone with as much class as her mother, like my ex-wife.

Divorce can be beautiful to observe from a distance but painful and bloody to execute, like ripping a rosebush out of a thick hedge with your bare hands. This is the real reason people stay in miserable marriages for the rest of their lives. Better to endure the dull ache for a lifetime than suffer the ferocious evisceration for even a flash.

I was more than a little anxious about meeting Oksana’s childhood friends and spending what was likely to be an entire three weeks drinking vodka with them. I had begun to distrust my drinking self again. I was not wholly predictable once that first mouthful crossed my lips. Bad things had started to happen when I drank—not all the time, mind you, but enough. Oksana and I fought almost constantly now when we were drinking. I would have to be careful in Russia. I’d heard stories. This was not a country to stagger around with your eyes half closed. Not if you valued your life. I would just have to be extra vigilant while I was there, stay away from the vodka, try to stick with beer. That was the answer. The possibility of not drinking at all was out of the question. My fellow countrymen would never forgive me.

Had I been spending the three weeks visiting Russia with her mother, none of these anxieties would have been an issue. Oksana’s parents had always been very civilized with me. I could never quite understand why. I suppose they were just very civilized people. They were much closer in age to me than I was to their daughter. I could just imagine the carnage if my seventeenyear- old daughter, my only child, my little princess, arrived home with a twice divorced, drunken Irish writer/construction worker, fourteen years her senior. I would have to be dug out of him. I’d have his guts for garters. I’d do time for the bastard. But they accepted me warmly into their lives. It might have been better for me if they hadn’t.

Oksana’s uncle picked us up at the airport. Even though it was summer, I was shocked by how bright and warm it was as we made our way out of the airport terminal. I suppose I had half expected Doctor Zhivago to bundle us onto the back of a snow sled. Oksana, of course, who was supposed to be with him, was nowhere to be seen. This did not shock me in the least. In New York she could disappear for a week without so much as a phone call, then show up casually like she’d just stepped out of the room to use the bathroom, saying she’d met an old high school friend and decided to stay over. Her uncle informed me that he hadn’t heard from her in two days.

On the ride from the airport I struggled not to picture her ferociously copulating with one of her former young lovers. This was beginning to feel like one of those Russian tragedies I’d been reading so much about. I pictured a duel on the foggy banks of the Volga at dawn before I left town.

On our drive back from the airport, Oksana’s uncle told me a little story by way of warning. A man had been stabbed the previous night just outside the building where I would be staying with Oksana’s grandmother. He was a local man. He had lived in one of the flats in the neighborhood his whole life. He had grown up there. He was in his early thirties. Oksana’s grandmother had discovered the body that morning as she left for work. She had called the cops to report it. The body was still there when she was on her way home at four o’clock that afternoon. Some kids were poking at it with a stick, so she had to call the authorities again. “But there is no need to worry. The ambulance has taken him away now,” he assured me with a bright smile before going on to explain to me how someone had gutted the guy, stolen his clothes and his sneakers, and that it was probably someone from the neighborhood. Possibly someone he knew. These kinds of things happened here, I was informed. I should be careful. People were poor around here, and some were desperate. I should be careful about being overheard speaking English or wearing clothes that made me stand out. I should never go out alone after dark. Ever. Welcome to Russia. Enjoy your stay. Next.

When we pulled up at her grandmother’s flat, I was greeted by the sight of a group of young children prancing around playfully in the courtyard. One of them held a short, thin stick with a bloody plastic glove on the end. He was scaring the other kids with it, threatening to poke them with it and then chasing them off, squealing, in the direction of the swings. A scrawny-looking street dog stole quickly across the yard and sniffed the bloodstained tarmac next to where we had parked. He gingerly lifted the other bloody glove in his teeth and scarpered off. This was not Doctor Zhivago, I thought to myself, although it did appear as if an operation had taken place here.

Oksana was still nowhere to be seen. I was having tea with her grandmother when she showed up unapologetically an hour later with some story about how she hadn’t realized the time. Oksana insisted that we ditch the family as quickly as possible so that we could go meet her best friend, Marina, and start drinking right away.

About an hour later, the three of us, Oksana, Marina, and I, were in a bar on the main drag near her grandmother’s flat. Well, I don’t know if you would classify it as a bar. It was an unadorned room with some cheap white plastic chairs and tables where you could buy either a small or a large glass of straight vodka. My large glass was served by a surly-looking lady who possessed all the warmth and grace of a hedgehog while retaining the distinct appearance of a small tugboat. She didn’t seem at all pleased with taking our money and having to perform the laborious task of refilling our tumblers, even though we were the only customers she had in the whole time we were there. The girls talked in Russian and I spent most of the time trying to figure out what the hell they were talking about. Oksana made it abundantly clear that she was not going to spend her vacation translating for me. Thank God for vodka.

Within a very short time we were sloshed. Unfortunately, it was only six thirty or so in the evening and the girls informed me that we had only just begun drinking for the night. I tried to say something about jet lag and needing to get to sleep at some point, but the girls had staggered off down the street with their arms around each other, singing something loud and bawdy in Russian. It was a bright sunny evening in the former city of Gorky and I decided I’d better go with the flow. We were off to find Marina’s husband, Loesha; apparently we were going out for the night to celebrate my arrival. Just then, a stray dog darted out from behind a parked car and dashed into the street, right next to me. The first car to hit it knocked it sprawling into the oncoming traffic in the next lane, where it was dragged for about twenty yards in the opposite direction before spinning off onto the sidewalk. It somehow managed to rise to its feet, and it took off yelping and hobbling past me down the block. Neither car paused; not a single person on the street stopped to see what had happened. It staggered on, whimpering, past the two girls, who were still singing, then veered off into a small park up ahead to the left.

“Didn’t you see what just happened?” I said when I caught up to the two girls.

“What?” Oksana said. Marina looked confused.

“That poor dog just got nailed by two cars crossing the

street.”

“Oh, don’t worry about it.” Oksana smiled. “It’s Russia,

Colin; that sort of thing happens all the time.” Then, with a roll of her eyes, she translated the conversation for Marina, who said something in a comforting tone to me that I didn’t understand. Oksana didn’t bother to translate it to me. I could see this was going to be a problem.

When I found the dog, he was lying in the uncut grass behind a park bench. He was whimpering and his body was shaking from the shock. His front leg was broken and he’d been scuffed up pretty bad; he was bleeding in a few places, but not severely. I sat in the grass and tried to comfort him for a while, petting him and telling him it was going to be OK. Two young boys not more than ten years old sat nearby on the swings, huffing glue out of a potato chip bag. They were too far gone to notice either me or the dog, or maybe they just didn’t give a shit. I must have been sitting there for a while, because when Oksana and Marina arrived they had Loesha with them. They had brought along an armful of large bottles of beer. I was glad to see them and, more importantly, the beer.

Loesha was a big lad, tall and handsome with a strong jaw and a kind face. I liked him right away. I felt a sense of relief as I shook his hand. I felt suddenly that I wasn’t going to be alone here. He spoke sincerely with me, having Oksana translate as he did so. He said it was admirable to take care of the dog the way I did, but there was really nothing to be done about it. He inspected the dog himself and surmised that it would be fine. The leg was definitely broken, but it would manage to live with it. He’d seen much worse. The dog had stopped shaking and had managed to sit up a little. Loesha gave it half of the sandwich he was carrying and it managed to wolf that down. The girls opened a few beers and Loesha handed me one.

“Welcome in Russia,” he announced proudly in an attempt at English as he gave me a broad smile and raised his bottle to mine.

A couple of cops passed by not ten feet away, chatting and casually observing the setting: two drunk teenage girls guzzling large bottles of beer; a pair of kids on the swings, one so far gone he couldn’t keep his eyes open, the other with his head shoved in a bag of glue, still huffing; Loesha and I with our beers hunkered next to a bleeding, whimpering dog. They continued on without so much as a pause in their conversation. Welcome in Russia, indeed, I thought to myself.

The following day, with my throbbing head as tender as a bruised tomato, we made our way to a small office somewhere in town to exchange some dollars for rubles. I had been warned by Marina and Loesha, who had come along to help with the transaction, that I should stay quiet once we were in the office. They were afraid that by speaking in English I would jeopardize the transaction. I didn’t quite understand their apprehension. It’s not like we were meeting an arms dealer in an abandoned warehouse. After all, this was a legitimate transaction in a legitimate currency exchange office.

The office we went to resembled the bar we had been drinking in the day before. It was a no-frills establishment. A woman sat behind a desk and glowered at us over her glasses. Apart from the pen she was twisting in her fingers and the big black phone perched ominously to the left of her elbow, there was nothing else of interest in the room to playfully ponder as I pretended to be Russian.

Marina placed herself in the chair opposite the lady to conduct the transaction while we stood behind her in silence, fidgeting with our hands. I felt like an idiot for not having exchanged the dollars in my bank back in New York. I hadn’t realized that to possess American dollars would be regarded as an offense against mother Russia. Marina handed the woman the hundred-dollar bill I had given her. We had decided to start small in case there was trouble. The woman fingered the bill precariously, staring at it and then at Marina, and then from Marina to us as if she was waiting for one of us to crack. She turned and held it up to the light of the window behind her, adjusting her glasses while still keeping the corner of her beady eyes on us lest we had any ideas about rushing the desk and overpowering her. The office door opened behind us and an elderly lady walked in with a small dog on a leash. The little dog leapt on my leg and started jumping up and down with excitement. I was relieved for this momentary break in the interrogation. Involuntarily I leaned to pet the dog and without thinking said, “What a cute little puppy.” That did it. I had blown our cover. The office lady spun around in her chair and glared at me. I might as well have torn up a portrait of the tsar and tossed it onto her desk. She erupted in a barrage of Russian invective directed at Marina. Marina shook her head and tried to plead with her, but it was too late. The lady was reaching for the phone. Marina spun around and, with a pleading, desperate expression, said, “Run.” Run? I thought perhaps I’d misheard her, or it had to be a Russian word

I didn’t understand. Marina couldn’t speak English.

“Run,” Oksana barked at me. Loesha grabbed me by the arm and we legged it out of there and up the street, leaving Marina there for what I could only assume was torture and quite possibly the gallows.

Loesha ushered us into a bar about a half mile away, checking to make sure we hadn’t been followed, and over a few glasses of vodka it was explained to me how a lot of these small exchange places were working in cahoots with the local police, setting up foreign tourists on counterfeiting charges. We stayed and drank, not daring to return home lest they lay in wait.

Later, when we did finally return to Oksana’s grandmother’s apartment, we found out that Marina had been released after about eight hours of questioning. The cops had then driven her home and confiscated her passport, but not before turning her apartment upside down searching for “the rest” of the “counterfeit” American currency. They demanded to know who had supplied it, but she stuck to her guns and told them it had been sent to her as a gift by a friend from America. They kept the hundred dollars that they already had for evidence. Loesha told me how things were so corrupt that the police and the exchange officers pulled this stunt on a regular basis. They’d take the money from the tourists, claim it was forged, and split it up between themselves and the exchange lady. Not a bad payday when you considered Loesha earned roughly thirty dollars a month as a car mechanic.

As a token of my appreciation and because I now realized I needed a full-time bodyguard to look out for my drunk Irish ass, I offered to pay for Loesha and Marina to come along with us on a boat trip up the Volga to Saint Petersburg. Neither of them had ever made the trip. They were ecstatic about the idea. We went down to the pier the next day and booked two cabins on a boat called the Turgenev. I tried to appear enthusiastic, but the truth was, I was vodka sick. I had developed some kind of chest infection and I was having difficulty breathing. I was hacking up a disturbing green bile that might have scared a lesser man into an emergency room. I should probably have eased off on the two packs of smokes a day, but I was on vacation, goddamn it. Oksana’s mother tried to convince me to stay on at the house with them and rest for a few days. But I hadn’t come this far to miss Saint Petersburg. I hid my cough as best I could and soldiered on as if nothing was wrong.

The morning before we were to leave on our trip, Oksana’s grandmother took us on a little trip to the graveyard. She brought along some garden tools and fresh flowers and went about tidying the family plot, weeding and pruning the small bushes, planting fresh flowers, and tilling the clay with a small rake. I took the time to browse the enormous graveyard, reading the dates of demise on the headstones and studying the faces in the small photographs on each, looking for some clue as to the great mystery of the unknown. The faces stared back, saying, “Hey, I don’t know shit, buster.”

I did begin to see a pattern develop. An unsettling number of the graves were those of young men, between the ages of roughly twenty-seven and forty-two. As I found more and more of these headstones, I began to wonder if I hadn’t missed some great Russian war. These were deaths that had occurred within the previous ten years; there were scores of them, sometimes two or three in a row. What could possibly have killed so many young Russian men? I wanted to ask Oksana or her grandmother, but I was afraid of revealing my ignorance of world affairs. Perhaps it was a great epidemic of some sort, but why, then, only the men? By the time I had returned to Oksana and her grandmother, I could contain myself no longer. I simply had to know. I had Oksana translate the question to her grandmother. She straightened herself and shook her head solemnly and then raised her hand to her mouth as if she were drinking out of a bottle.

“Vodka,” she said.

Vodka? I was astounded. She continued in Russian and Oksana translated, saying that since perestroika, the young men had had trouble finding work to support their families, so they drank instead. I was floored. It was like witnessing the aftermath of a mass suicide of a generation of men. How was it possible that I’d never read a single thing about this, never once heard it mentioned? It explained the emptiness I had felt since I had arrived. This was not the Russia I had envisioned. This was the afterbirth of some savage delivery. Blood had been spilled in the theater. The great country was anew at the cost of thousands, hundreds of thousands perhaps. I comforted myself with the thought that this was the way all things were born on God’s green earth and vowed to lay off the cheap vodka and to go see a doctor about my chest infection the moment I touched down again in New York.

EIGHT DAYS ON THE VOLGA

A DIARY

DAY ONE

We are on an old boat called the Turgenev. We said good-bye to Nizhny Novgorod yesterday morning. I drank a bottle of samagon with Loesha before lunchtime, blacked out, and woke up cold, huddled on a bench on the top deck at six thirty this morning. Less than twenty-four hours into the trip and Oksana has stopped speaking to me already. My chest is worse than ever. I might not survive this voyage.

DAY TWO

We made a brief stop in Yaroslavl today to visit an old gramophone museum. The rest of the day, the four of us drank sweet red wine in our cabin. Oksana will neither speak to me nor translate what the others are saying. Thank God for the wine.

Later the girls went to a disco up on deck and Loesha produced a large glass jar of weed. There’s enough here to have us chained together in a cold cell in Siberia for the rest of our lives if we are caught. Thank God for the wine and the weed.

DAY THREE

Another day of drinking red wine and waiting for Oksana to lift the verbal embargo. I spent the day listening to the radio, staring out the window, scribbling in my notebook. There are four wooden houses in a clearing near the river’s edge. A ribbon of smoke files past them almost horizontally over the rooftops. The sky is blue, and white shirts are being pegged to a clothesline by a woman in a red apron. A barechested man is cutting logs with a saw that looks like a huge violin bow. The land is flat here, so there is nothing to bracket any of this. There is a green tent on a beach and a dog barking, a broken wooden pier and a dirty yellow boat upturned in the grass next to it. And here is a church and another church and another. I have been told that at one time there were sixty thousand churches along the Volga. They are empty now and crumbling, their minarets silhouetted in the afternoon sun like the helmets of some ancient tribe. We are drifting along on the Volga not more than twenty-five feet from shore. I could jump overboard here and walk off into the woods. No one would ever hear from me again.

DAY FOUR

We stopped in Rybinsk today. The four of us took a walk and bought jars of pickled mushrooms, dried fish, and various knickknacks. I bought a small aluminum statue of a drunk with a bottle raised to his head. Then I got into a screaming match with Oksana in the pouring rain. She was wearing a tight white T-shirt and hadn’t bothered to wear a bra. I had to endure wolf whistles from the boat crew as she stormed ahead of me onto the boat on the way back. One of them said something loud enough for Oksana to hear, and I heard her answer, “Spacibo”: Thank you.

DAY FIVE

Oksana made me a sardine sandwich today. It is a peace offering. The first gesture of affection she has shown me in days. The boat will not stop today, she tells me. We are between Goritsy and Valaam and crossing Lake Ladoga, the largest lake in Europe. Land is no longer visible, and I feel particularly vulnerable. I’m drinking heavily today to quell my fears, even though my body is screaming at me to stop.

DAY SIX

Today we reached Valaam Island at around ten in the morning, and she was in love with me again. We walked with Marina and Loesha five miles through the woods to the Valaam monastery, high on a hill. There was a definite ache in my liver this morning. I prayed it was a walking cramp and made a silent vow to stop drinking the cheap vodka we had been purchasing.

Inside the monastery two young monks were on their hands and knees scrubbing the immaculate stone floor. Others went about reverentially polishing gold and brass chalices, rails, and crosses. Every square inch of the walls, the ceiling, and the dome far above us was covered with rich colorful frescoes so awe-inspiring that it caught my heart by surprise. Art for God’s sake. And in that instant, I could believe too. I wanted to lie down and hold my cheek against the cold stone floor, because I felt that somewhere here in this great silence was the real prayer.

DAY SEVEN

Today we visited one of the summer homes of Catherine the Great. While we were walking around, a young boy came up to show me a cricket he had cupped in his hands. Oksana leaned over to look and smiled at the boy. The boy’s mother grabbed his arm and yanked him to her side. The cricket fell from his hands and made a hop for freedom, but as the boy stumbled to his mother’s side, he accidentally stepped on it.

“Why are people so cruel?” Oksana said, and she began to cry. “I want to take the little boy home with us. Did you see his face?”

“It was an accident,” I said.

“No it wasn’t. People are mean and cruel. They all are, even you and me. We’re all mean. People are horrible. Only animals and little children are good. I can’t stand it anymore.” She turned away from me and started off toward the bus that had taken us there from the boat. I tried to follow but she turned on me.

“Leave me alone. I want to be alone. I want to be little again.”

DAY EIGHT

We were in Saint Petersburg today. Oksana and I went to see Pushkin’s home.

“I’m not in love with you anymore,” she said as I watched a cat that had snuck in and nestled itself in Pushkin’s old writing chair. An old woman in a blue head scarf noticed the cat and stepped over the red rope, scolding and slapping her leg with her hand. The cat bolted off the chair and managed to scale four shelves of books before she caught him.

“You’re breaking up with me in the middle of our vacation?” “It’s over.” I was tempted to step over the rope and take a seat at Pushkin’s desk for a moment. Russian writers suddenly made more sense. Maybe he kept an old musket in that desk drawer. I could end it all here, put a stop to all this drama; one more gunshot as a punctuation mark on the historical literary landscape. It is late as I write this. I am alone again in our small cabin, drinking cheap vodka straight from a plastic tumbler. She is gone with Marina to the disco. Loesha has slipped down to the other cabin to fetch the jar of weed. Maybe that will help take the edge off a little. It is going to be a long ride back.

I had another week of Russia to endure now that I was single. I tried to stay focused on getting my ass back to New York in one piece. Things had started to get a little crazy before we made it back to Nizhny. People from other boats, complete strangers, would approach me in the small villages where we stopped for supplies and ask me to go drinking with them or if they could possibly have a picture taken with me. Loesha explained that word of my drinking exploits had spread. People wanted to see the crazy Irishman. The orangutan was loose. I had become the town entertainment. At first I thought it was just a little paranoia from all the weed we’d been smoking, but apparently people were really staring at me. Loesha had to remind me that I was the only non-Russian that he had seen on the whole river trip. A waitress on the Turgenev had told us that in the five years she had worked on the boat I was the first non-Russian she had served. It didn’t help that I had been spotted sleeping on the deck on numerous occasions or trying to throw my screaming girlfriend overboard into Lake Ladoga in broad daylight. This did not bode well. This was not a country where you wanted to stand out as a crazy drinker. Not in a country where the life expectancy of the average drinking male is about thirty-five years old. It was too late to stop drinking now anyway. I couldn’t afford to go into withdrawals in the middle of my trip. I would need at least four days alone in my apartment to detox from this one. I would just have to monitor my alcohol intake for the rest of the trip, keep a bottle near the bed for when I woke up, maintain a steady buzz, keep my chin up. The liver had only just begun to hurt; there was plenty of fight left in the bastard yet.

Before we left Russia, Oksana’s uncle and her mother took us on a little road trip to the country to see Oksana’s greatuncle. On the way there we passed through Dzerzhinsk, a town the New York Times has called the most tainted city in the world. Oksana’s uncle advised us to keep the windows up while we passed through so that we wouldn’t breathe in the radiation. I couldn’t tell if he was serious or not, but I was willing to listen.

Thankfully, Uncle Kosha lived beyond the city line in a wooden cabin way out in the country. He came rushing out of an old tin shed to greet us with outstretched arms when we pulled up in front. Here was Pablo Picasso’s long-lost twin brother; I was sure of it. The resemblance was uncanny. His wife, who had been down in the garden weeding the vegetables, hurried up, wiping her hands on her apron, and embraced each of us in a warm hug before ushering the party indoors to find their beautiful daughter, Anna, who had dashed off to put on a clean dress and fix her hair when she had seen the car approaching up the field.

This was the Russia I had read about. There was no phone here to warn them of our arrival. No e-mail in advance. This was how it had been everywhere once upon a time: big pleasant surprises in the simplest of things.

The women shoved us into the comfortable old worn chairs around the living room and went about fussing over us, handing us drinks and grabbing laundry off the clothesline above the stove, kicking boots underneath the chairs, sweeping the dust out the door, while Kosha ran off to alert the neighbors to prepare for a party. It reminded me of my grandparents’ house when I was a kid: the smell of a wood fire, furniture that had been sat in for generations, a floor that had been worn into soft grooves around the kitchen table. I had almost forgotten what it was like to be in a house like this.

For the next four hours or so they prepared dish after dish: cucumber, beet, and potato salads all fresh from the garden; there was a chicken plucked and herring boned; mushroom caps were stuffed and served dripping in butter; wine was sloshed into our goblets and we drank and ate and the neighbors arrived with dessert and we sang songs. Picasso took Oksana and danced with her in the garden as the little black-and-white collie spun himself in giddy circles, yapping.

Then came the late afternoon and the vodka; that was when the real drinking began, a shot for every toast. We raised a drink to Oksana and one to her mother and one for her father, who could not be there. At this point the ladies held their hands over their glasses when Picasso came around to fill them again. They would sip their vodka from here on in. Oksana’s uncle was excused because he had to drive us back to the city. Oksana gave me a kick in the shin under the table and a raised eyebrow above it to signify that I had to keep going. Pablo was just warming up, it seemed: one for the food, and the ladies who prepared it; another for the Irish and another for the neighbors who had arrived from across the fields with the dessert. I was relieved to see the bottle of vodka run dry after about five shots. I was having trouble getting them to my mouth without spilling them at this point, but Picasso was nowhere near done yet. He had Anna fetch another bottle from the room and bring it to the table. But wait, hold up a minute, what was this? This wasn’t vodka. It looked like some kind of hospital bottle. It didn’t have a label, but it was definitely hospital brown. Like a large medicine bottle.

“What the hell is that?” I whispered to Oksana. I got another kick underneath the table. “Is that some kind of hospital cleaning fluid?”

“Shhh.”

“Is that from a hospital?”

“Anna is a nurse.”

“I can’t . . .”

“Don’t embarrass me or them. Just drink it.”

“It could kill me.”

“Just drink it and stop being a big baby.”

Baby? Did she just call me a baby? I’m no damned baby. Don’t you dare call me a baby. I will drink every drop of alcohol east of the Volga. I will drink turpentine, gasoline if I have to. Fill my glass up there, Pablo, you old crotch-muncher. Let’s party.

I still don’t know what was in that bottle, but it burned like hell. My tongue shriveled and my throat squeaked and tears rolled down my face. Pablo poured us another one. The second one wasn’t so bad now that my taste buds had been seared off. The third was like water.

I decide to take this opportunity to I tell her how I really feel. I tell her that I’m unhappy in the marriage and that I want a divorce. She hopes I rot in hell. So I move to the couch in the basement.

Within a week Bill and I have parted company. He has apologized for his indiscretion but I can’t look at him anymore without wanting to rip out his throat. He comes by when I’m not there and takes his few personal items, then has me served with papers seeking half the business. I tear up the papers and throw them in the trash can. I have never seen him or spoken to him since.

The adoption agency has called; they have a child for us in South America. She’s almost two years old. We are to fly immediately to meet her and take her back to the States. Brigitte tells me that this is the last thing she wants me to do for her. She cannot do it alone. The agency wouldn’t allow it. She needs a husband. I agree to go along.

We agree that when I come back I will find an apartment somewhere nearby and we will work something out so that we can take care of the child together.

Three days before we fly to Ecuador I find out that Brigitte has emptied my bank accounts, sold the stocks I had purchased, and maxed the credit cards that were in my name. I’m suddenly about forty thousand dollars in the hole. I am completely broke. I have to call Tony to borrow money for gas. She won’t lend me twenty dollars of my own money. My friend who’s a lawyer begs me not to go through with the adoption process. He tells me that I’ll lose everything. I know he’s right, but I feel guilty about falling in love with someone else, so I go along as a form of penance.

My friend steps in and takes care of the business while I’m gone. The poet Rick Pernod and I decide to become business partners and make a fresh go of it at the café. I tell Oksana that I am in love with her, and she tells me she will be waiting for me when I return from Ecuador. Brigitte and I travel to Ecuador. My daughter is a beautiful, healthy two-year-old, and I cry the moment I take her in my arms. I had never expected to fall in love with her instantaneously. She is the most beautiful child I have ever seen in my entire life. I look into her eyes and I know her and she knows me. I return from Ecuador a few days early, as agreed, to set up my own apartment and prepare for my daughter’s return. Oksana and Rick are waiting for me at the airport. I am an emotional basket case.

I borrow money from Tony and rent a one-bedroom apartment in Riverdale, up on the Parkway. I buy a new bed and move a few personal items out of the house. Brigitte returns from Ecuador with our daughter. She refuses to let me see her, just as my lawyer had predicted. She hires an expensive lawyer of her own and announces she wants full custody. After a brief struggle and the advice of two other attorneys, I relent. I give her everything. The house, the money, Molly, and our daughter. She moves away and I have not seen or heard from her since.

I have an apartment in Riverdale that I can’t afford. I have a ten-year-old car in need of repair. I’m completely broke. My credit is destroyed. The coffee shop is barely paying its own bills.

I close the café on a Friday night after I have signed the divorce papers. I lock the doors. Oksana has gone out for the night with some friends of hers. I am alone. I turn down the lights and take out a bottle of absinthe someone sent Rick and me as a gift from Prague. It’s the real deal. The illegal stuff with the wormwood. We were saving it for special customers. I pour a small glass of it. I dip a spoonful of sugar into it, remove it again and then light the absinthe-soaked sugar. It burns with a blue-green flame. I haven’t tasted alcohol in eight years. I will have one drink just to see what it tastes like. I want to drink again. I don’t want to be a drunk. I’ve just decided that I’m going to have a few drinks every once in a while. I deserve it after all I’ve been through. The flame is hypnotic. As it dances I picture van Gogh in Arles, Joyce in Paris, Hemingway in Spain. I was meant to drink. Why should I deny myself this right? I was born to drink. I drop the spoon into the glass and stir. I take it in my fist and smell its sharp menthol fumes. I lift the glass and my arm almost doesn’t want to bend. I force it. It hits my lips and I don’t stop until the glass is empty. My eyes water. I set the glass down and brace myself. My throat burns. A hot flame runs all the way to my gut. I’m still alive. That tasted good. I think I’ll have one more. Just one. After three I decide I’d better just take the bottle home with me. I don’t want to get drunk and then have to drive home. I take the scenic route home through Fieldston. There’s something familiar about myself that I can’t quite put my finger on, but I like it. I go home and finish the entire bottle. I’m thirty-one years old. I’m broke. I’m divorced for the second time. I have a teenage girlfriend. I’m drinking again.

IT’S DRINKING AGAIN

See, I’m not an alcoholic. I just drank a bottle of absinthe and I’m fine. You people are crazy. Alcoholic! Ha. Jesus, it’s nice to be drinking again. I’m Irish; I’m a writer; who the fuck did I think I was kidding? So I was young and a little confused. Quitting drinking at the age of twenty-three! I can’t believe I have denied myself this pleasure for eight whole years. Never again! I will never put myself through the misery of being sober ever again. Sober life sucks ass. It’s no wonder all my cousins stopped inviting me to their little parties. What a bore I was. And those muscle cramps in my gut, gone. Gone. They were stress-related. I was all bunched up. I was a tightwad miserable fuck. All I needed was a good drink to relax. My God, I feel like an idiot. How? How could I have been so stupid? AA! Jesus. What a bunch of dry old farts. What a miserable, despicable collection of rejects. What a sad, pathetic little family of losers. What they need is a good drink. Every last one of them. I cannot believe I associated myself with those people for eight whole years. My family must have thought I’d lost my mind. I can’t wait to have a few drinks with the lads again. Or a nice bottle of beer with the old man next time I’m home. Jesus, I can’t wait. Drink like a grown-up. You know what? I’m glad I went to AA. I’m glad I went through a couple of therapists. It was not a complete waste. At least now I know myself. I will always be able to monitor my own drinking. If my drinking begins to cause problems, I’ll check myself. I just have to keep an eye on it. If it gets out of hand, if I find myself crossing any lines, I’ll just pull it together, knock it on the head for a week or two. God knows that shouldn’t be a problem. I didn’t drink for eight years. A week or two is a joke. If I watch it, if I’m careful, I’ll be able to enjoy this luxury for the rest of my life. I am so damned happy I could cry. Thank you, God, for giving me this beautiful opportunity to drink again. I promise you I will continue to pray. I will keep the twelve steps in mind and continue to live a good, responsible life. All I have to do is keep my drinking under control. It’s that simple.

TWO WEEKS LATER

It was one in the morning on a hot Friday night. I was sitting in the dark by the open window, watching the traffic roll by on the Henry Hudson Parkway. There’s something about the sound of passing traffic that normally soothes me, but it just wasn’t working on this particular night. Nothing was working. I’d finished the two bottles of wine and started in on the vodka. Oksana was gone. We’d had one of those boozed-up fights the previous night that makes Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? look like a children’s fairy tale. She had stormed out, saying she was going back to live at home with her parents. Again. I was glad she was gone. I needed time to think. Everything was happening so fast I could barely keep up with it all. I was just out of a six-year marriage. My café-bookstore was closing. I was broke and back working construction. I needed a smoke. A nice fat joint would sort me right out. That had always worked before. I’d just go get myself a nice little dime bag of weed. Just enough to take the edge off. I’d come home, turn the lights down, listen to some Floyd. Chill the fuck out. Just like the old days. I’d just have another little glass of vodka for the road. God, it was good to be drinking again.

I took a ride in my old Honda Civic to White Plains Road. The same area where I’d been beaten and left for dead ten years before. It was time to give it another shot. Surely it was more civilized now.

I spotted a few guys hanging out near the old street corner. They looked cool. I was good at this. I have a real feel for people. I can sense danger a mile away. One of the guys, a young black kid, gave me the nod. I nodded back. I was in business. He flipped his head left to right a couple of times, checking for cops, and waved me onto the side street. I made the turn and pulled in at a hydrant. I left the car running and stepped out to greet him as he walked toward me.

I leaned against the front fender and folded my arms nonchalantly. I wanted him to know that I was cool, that we were the same, he and I. We were both cut from the same cloth. I’d done a little dealing myself back in the day, in London. I knew the scene: a lot of posturing, head-nodding, grunting, toughguy shit. I could almost taste the weed already. Eight years without a smoke. This was going to be great. The kid was moving toward me, crossing the street at a brisk pace. And now that I could see him up close, he looked a little crazed. Maybe I’d misjudged this motherfucker. I’d had a lot to drink. It was too late anyway. I was just going to have to roll with it and hope for the best. Maybe I shouldn’t have pulled onto this side street. Maybe I shouldn’t have gotten out of my car. Maybe I shouldn’t have left my apartment. Maybe . . . He had a knife in his hand. He must have pulled it from his waistband. I definitely didn’t see that coming. Fuck.

“Give me your wallet, muthafucka.” He had stopped about an arm’s length away and he held the knife toward me. It was a big knife. Shiny. “Give me your muthafuckin’ wallet, asshole.”

“Fuck you,” my mouth said.

“What d’you say to me, mutherfucker? You wanna die? Give me the muthafuckin’ wallet.”

“Go fuck yourself.” There it was again. That mouth of mine sure did have a life of its own. He swiped the knife across my middle. I managed to pull back just a fraction without making a big to-do about it. He’d missed. Maybe he meant to miss.

“Give me the wallet, man,” he continued. He looked a little perplexed now, as if this was just way too much work. He was obviously used to a little more cooperation than this. “You want to die?” he said.

“You’re not getting my fucking wallet, asshole,” my mouth said with great confidence. He swiped again. This time he was pissed. He slashed the knife across my throat in a wild swing.

“Give me the wallet!” he shouted. “You want to die here?” I casually reached my left hand to my neck and rubbed my fingers across my throat. I held my hand up to my face and looked at the thin streak of blood across my fingers. He’d cut me alright, but barely. It was only a nick across my Adam’s apple. No big deal. He really was pushing it, this kid.

“OK. I’ll tell you what I’m going to do,” I said, pausing to collect myself. It was time for some diplomacy here. This was beginning to get serious. I was going to have to calm down and negotiate. Treat him like a businessman. That’s it. Give the guy a little respect. They love a little negotiation, these guys. They want to feel like they’re being heard. That’s cool. I could roll with that. “I’m going to take my wallet out and I’m going to hand you the cash. But I keep the wallet—” Slash. There he was with that knife again. This time he connected. I lifted my right arm and sure enough there was a huge gash running across my arm between my elbow and my hand. It was wide open. I could see a white wall of flesh. It was deep. This kid was a tough negotiator, no doubt about it. I actually laughed a little. He’d really taken me by surprise with that one. It was time to wrap this thing up before things got out of hand.

“OK,” I said, holding my arm up so that he could get a good look at the cut. “If you put that knife near me one more time, I’m going to take it off you and shove it up your fucking ass.”

“Are you fuckin’ crazy, man . . .”

“I’m going to take my wallet out and give you the cash,” I said, reaching for my wallet. “I’m going to give you the cash and I’m going to keep the wallet.” I had the wallet out. I opened it and he waited, shifting nervously from foot to foot while I removed the cash. There was maybe two hundred dollars in there.

I handed it to him. “Now go fuck yourself, asshole.” He grabbed the cash from my hand and ran off up the side street. When he was about twenty feet away he turned and shouted, “You’re fuckin’ crazy, man. You need fuckin’ help.”

“Fuck you, tough guy,” I shouted after him. It was then that I noticed that a few guys had gathered across the street. They made their way toward me. I was in no hurry to go anywhere at this point. I put my wallet back in my pocket as they gathered around. There were maybe four or five of them. Young black kids.

“He cut you, man?” one of them asked.

I held up my arm so that they could see.

“Fuck, man,” he said, taking a good look at it. “He fucked you up pretty good, huh?”

“Yeah, he’s a real tough guy. He a friend of yours?”

“Naw, man,” one of the other kids said. “We don’t know that guy.” They were all huddled around, inspecting my arm. It did look pretty bad. I felt alright about it somehow. It didn’t hurt too badly.

“Any of you guys got a smoke I could bum?” I asked. A couple of them dug into their pockets. One of them handed me a smoke, another held out a light for me. “Well, guys, it’s been real, but I gotta get myself to a hospital.”