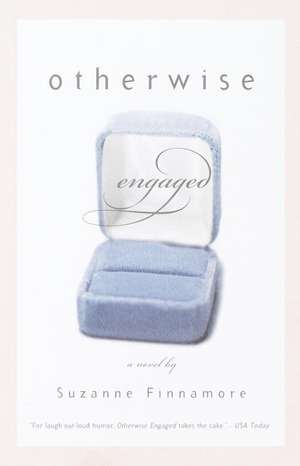

Otherwise Engaged

Autor Suzanne Finnamoreen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2000

When Michael pops the question, Eve is deliriously happy. She tells grocery clerks. She subscribes to bridal magazines. She delights in the rainbows that shower from the one-carat (okay, .81-carat) ring on her hand. For two days. As the cumulative stresses of ordering invitations, finding a dress, and organizing the Perfect Honeymoon fry Eve's nerves, the very real prospect of being with one man for the rest of her days reverberates through her consciousness like a Chinese gong. Suddenly the sight of Michael's discarded socks on the floor and his passing mentions of his former live-in French girlfriend incite doubt, argument, and public fainting.

Uproarious, insightful, tender, Otherwise Engaged dashes our soap-bubble fantasies in favor of a hilariously realistic walk to the alter.

Preț: 67.65 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 101

Preț estimativ în valută:

12.95€ • 13.44$ • 10.80£

12.95€ • 13.44$ • 10.80£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375706424

ISBN-10: 0375706429

Pagini: 224

Dimensiuni: 132 x 207 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0375706429

Pagini: 224

Dimensiuni: 132 x 207 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Suzanne Finnamore lives in Larkspur, California.

Extras

He did it. I said yes and checked my watch. 7:22 p.m.

I sneak a pen out of my purse and write the time down on the palm of my hand, in what I hope is a nonchalant fashion. I am excited and at the same time I feel there is a possibility of an inquiry.

He didn't kneel. It's unlikely I would marry someone who did. From then on, I would live in fear of Whitman's Samplers. Tandem bicycles. Someone who knelt would need me to give up my name and bake pies while his aging mother cried out in pain from the next room.

Exhilaration. Also something darker: a sense of triumph. It is primal, furtive; my ovaries cracking cheap champagne. I win. Those two words; that's exactly how I feel. Happy, but not in an I Knew It All Along way. Definitely in a Contestant Who Has Won in the Final Round Despite Major Setbacks way.

And the Harvard professors who say a woman is as likely to be married after thirty-five as to be abducted by terrorists? May they fall into open manholes, where hard-body lesbians with blowtorches await them.

I am thirty-six years of age.

I need to write it all down. Exactly what was said, exactly what happened.

It all began Sunday morning. I woke up and heard him padding around the kitchen of our San Francisco flat: making coffee, unfolding his New York Times. Sun dappled the crisp two-hundred-thread-count cotton sheets. Outside the bedroom window, two finches nuzzled on a branch. In the kitchen, Molly O'Neill was freeing kumquats from their humdrum lives. At that moment I decided it probably wasn't going to get any better than this. The free introductory trial period was over.

He brought in my coffee, murmuring the theme song from Goldfinger. "Goldfinger . . . he's the man, the man with the Midas touch . . . the spider's touch."

He was planning his day. It was going to be a day like any other. It would be free of confrontation, conflict, or commitment, anything that could remotely lead to a subpoena. Michael is what his therapist calls change averse. The survivor of a bitter divorce, which he refers to simply as The Unpleasantness.

The day he had planned was going to include me, but it was going to revolve around him. Just a nice Sunday is what he would have called it.

It was my task to set the earth spinning the other way.

I took his hand, and said, "You know what?" Pleasantly, as though I had some interesting good news to share with him.

"You need to decide about us. Now." He tensed, his eyes flitting around the room. A paperboy caught in the grip of a mad clown.

There ensued a period of silence. He stared past my right shoulder, transfixed by a point just outside the present. He had decided to go blank.

I cataloged events for him, since he was so bad with time.

"We've known each other three years. We've been living together six months."

I asserted that I wasn't going to be like Gabrielle, the hair model who lived with him for four years and got the Samsonite luggage.

"I love you," I said. "But I can't just stay in limbo."

What's wrong with limbo? I heard him thinking. Limbo is fantastic.

"Especially if we want to have children," I said.

His face went white. He had understood that one word, "children." Ten years ago his first wife, Grace, left him and moved to Vermont along with Michael's three year-old daughter, Phoebe. Every year, Michael cries on her birthday. Phoebe calls her stepfather Daddy, and Michael, Michael.

"I understand if you can't move forward," I said. Beat. Sip of coffee. Sad smile. "But I have to."

I added that if he didn't marry me, he would probably end up alone. A few meaningless and shallow affairs with a certain type.

"Users," I said. "Women who don't want a commitment."

His face, I thought, lit up.

"An old man in a rocking chair," I said. "Eating Dinty Moore beef stew out of cans."

This is what he eats when I am gone. This and corn. Michael turned forty-four last July. Together we are about a hundred.

"We're meant to be together," I said. "But if not you, I'll move on and find someone else."

I wondered how many women were lying that same lie at that exact moment. In truth he would have to blast me out with dynamite, just like Gabrielle. Holding on to the front doorjamb with the tips of my fingers and screaming. Hooking my feet around the wrought-iron banister.

He said he would think it over. The fact that he had to think it over made me want to cry and break things. I looked out the window. The birds were gone.

"I guess I always knew it would come to this," he pronounced, deadpan.

He slumped quietly out the door and I heard his motorcycle start up. I looked out the window as he drove away. He had his full-face Shoei helmet on. He looked like a large blue-headed beetle, moving away at high speed. The way he was going, one might think he would never return. But just like the little rubber ball attached to the toy paddle with a long elastic string and a single staple, he has to come back. All his things are here.

When he returned four hours later we both pretended it hadn't happened. I roasted a chicken; we ate it in front of 60 Minutes. I commented on how fine Ed Bradley looked. How tall and sleek, like a panther. Michael is five foot nine, Caucasian. Serial dreams of being in the NBA.

The following day he left for an overnight business trip to Colorado. The timing was impeccable. One night to think things over, to imagine a world without a sun. That night he called me from his hotel in Denver, saying there was something he wanted to talk about when he got back. Code word: "Something."

"Have a safe trip home," I said. "Darling." I hung up and made reservations at the Lark Creek Inn in Marin. Chef Bradley Ogden, home of the eighteen-dollar appetizer. That night I sleep fitfully. I am what my mother used to call overexcited. I think about what if the plane crashes and he never gets to ask me. I will tell people he did, I decide.

I felt extremely focused.

The next day, Tuesday. He comes home around four in the afternoon. He actually runs to the kitchen, to find me.

He loves me, I am thinking. Also: Baby, you are going DOWN.

We embrace. His skin feels cool, as though he had flown home without the airplane. He has on a thick moss-green plaid flannel shirt which he has purchased in Santa Fe, probably in a Western store with a wooden Indian outside. It soothed him, buying that shirt. I can see that.

At six we dress for dinner in silence. I watch him. And when I see him pull his gray suit out of the armoire, I know. It's not his best suit, but it's my favorite. Single-breasted. With the suit, he puts on his black merino-wool sweater. Another clue. A simple shirt would've been one thing. Or a black knit tee. The black tee would say, I'm sporty but not serious. It would say, I know how to wear a tee shirt with a suit, I'm a good catch. Try and catch me. The merino sweater has a collar and three neat buttons. It says, I'm caught. And I'm taking it like a man.

I wear a black sheer-paneled skirt and a long knit jacket from my first trip to Paris. Black hose, black heels. I put on my earrings with my eyes still on him. I hook the wire through the hole, blind.

We drive across the Golden Gate Bridge without speaking. Black Saab, top down. I'm wearing a velvet hat and dark sunglasses. We are listening to the jazz station. This would make a good commercial, is what I'm thinking. Also I am wondering how I am going to live if he doesn't ask. We would have to break up immediately, tonight. This instant. My mind flips back and forth, a fish on the deck.

We arrive and valets grab the keys from his hand, open doors. Once inside, we are quickly seated. Time is speeding up, not slowing down as in emergencies. Table in the corner. The perfect table, I am thinking. Now he has to ask me. The center tables are ambiguous. The corner tables are definite.

They pour the wine. He tastes it, nodding. He orders our food; I let him. I can't feel my legs.

There is a long, flesh-eating silence. And then he says, "So what should we do?" "About what?" I ask, caressing the stem of my glass. I am going to make this as difficult as possible for him, I don't know why. There seem to be bonus points involved.

"You know what," he says. He has a wide, strange smile, like a maniac who is about to reveal that he is strapped full of Plastique explosives.

"What what?" I ask.

Now I am smiling too. I can't help it.

"Maybe we should get engaged." He says it.

"Maybe we should," I say.

I take a long slow sip of wine. I have seen our cat, Cow Kitty, whom we call the Cow for short, do this to bees. First he stuns them and then he watches them die.

"Do I have to do it now?" Michael asks. He sees the waiter headed toward us, a large tray held expertly overhead. He has ordered the Yankee Flatiron Pot Roast, with baby vegetables. $28.95. "Can't we wait until after?" he says.

"No. You have to ask me now," I say. The pot roast is an incentive, making sure it's hot when he eats it. I'll get this out of the way, he's thinking, and then there will be pot roast.

"Will you marry me?" he says.

"Yes," I say.

We kiss. People around us continue to eat. It seems there should be something else, but there isn't. It's just a question, after all. Five words, including the answer. The pot roast arrives and he eats it all. I barely touch my cod; it is impossibly pale. I can see the plate through it. It occurs to me that I may be dreaming. I pinch my arm.

"What are you smiling at?" he asks.

"Nothing," I say. I'm awake, I don't say.

I always thought I would cry, but I don't. I laugh.

Later we get on the speaker phone and call my mother, who lives in Carmel with my stepfather, Don. She whoops.

It's difficult not to feel insulted. We finally found a buyer for the Edsel.

I sneak a pen out of my purse and write the time down on the palm of my hand, in what I hope is a nonchalant fashion. I am excited and at the same time I feel there is a possibility of an inquiry.

He didn't kneel. It's unlikely I would marry someone who did. From then on, I would live in fear of Whitman's Samplers. Tandem bicycles. Someone who knelt would need me to give up my name and bake pies while his aging mother cried out in pain from the next room.

Exhilaration. Also something darker: a sense of triumph. It is primal, furtive; my ovaries cracking cheap champagne. I win. Those two words; that's exactly how I feel. Happy, but not in an I Knew It All Along way. Definitely in a Contestant Who Has Won in the Final Round Despite Major Setbacks way.

And the Harvard professors who say a woman is as likely to be married after thirty-five as to be abducted by terrorists? May they fall into open manholes, where hard-body lesbians with blowtorches await them.

I am thirty-six years of age.

I need to write it all down. Exactly what was said, exactly what happened.

It all began Sunday morning. I woke up and heard him padding around the kitchen of our San Francisco flat: making coffee, unfolding his New York Times. Sun dappled the crisp two-hundred-thread-count cotton sheets. Outside the bedroom window, two finches nuzzled on a branch. In the kitchen, Molly O'Neill was freeing kumquats from their humdrum lives. At that moment I decided it probably wasn't going to get any better than this. The free introductory trial period was over.

He brought in my coffee, murmuring the theme song from Goldfinger. "Goldfinger . . . he's the man, the man with the Midas touch . . . the spider's touch."

He was planning his day. It was going to be a day like any other. It would be free of confrontation, conflict, or commitment, anything that could remotely lead to a subpoena. Michael is what his therapist calls change averse. The survivor of a bitter divorce, which he refers to simply as The Unpleasantness.

The day he had planned was going to include me, but it was going to revolve around him. Just a nice Sunday is what he would have called it.

It was my task to set the earth spinning the other way.

I took his hand, and said, "You know what?" Pleasantly, as though I had some interesting good news to share with him.

"You need to decide about us. Now." He tensed, his eyes flitting around the room. A paperboy caught in the grip of a mad clown.

There ensued a period of silence. He stared past my right shoulder, transfixed by a point just outside the present. He had decided to go blank.

I cataloged events for him, since he was so bad with time.

"We've known each other three years. We've been living together six months."

I asserted that I wasn't going to be like Gabrielle, the hair model who lived with him for four years and got the Samsonite luggage.

"I love you," I said. "But I can't just stay in limbo."

What's wrong with limbo? I heard him thinking. Limbo is fantastic.

"Especially if we want to have children," I said.

His face went white. He had understood that one word, "children." Ten years ago his first wife, Grace, left him and moved to Vermont along with Michael's three year-old daughter, Phoebe. Every year, Michael cries on her birthday. Phoebe calls her stepfather Daddy, and Michael, Michael.

"I understand if you can't move forward," I said. Beat. Sip of coffee. Sad smile. "But I have to."

I added that if he didn't marry me, he would probably end up alone. A few meaningless and shallow affairs with a certain type.

"Users," I said. "Women who don't want a commitment."

His face, I thought, lit up.

"An old man in a rocking chair," I said. "Eating Dinty Moore beef stew out of cans."

This is what he eats when I am gone. This and corn. Michael turned forty-four last July. Together we are about a hundred.

"We're meant to be together," I said. "But if not you, I'll move on and find someone else."

I wondered how many women were lying that same lie at that exact moment. In truth he would have to blast me out with dynamite, just like Gabrielle. Holding on to the front doorjamb with the tips of my fingers and screaming. Hooking my feet around the wrought-iron banister.

He said he would think it over. The fact that he had to think it over made me want to cry and break things. I looked out the window. The birds were gone.

"I guess I always knew it would come to this," he pronounced, deadpan.

He slumped quietly out the door and I heard his motorcycle start up. I looked out the window as he drove away. He had his full-face Shoei helmet on. He looked like a large blue-headed beetle, moving away at high speed. The way he was going, one might think he would never return. But just like the little rubber ball attached to the toy paddle with a long elastic string and a single staple, he has to come back. All his things are here.

When he returned four hours later we both pretended it hadn't happened. I roasted a chicken; we ate it in front of 60 Minutes. I commented on how fine Ed Bradley looked. How tall and sleek, like a panther. Michael is five foot nine, Caucasian. Serial dreams of being in the NBA.

The following day he left for an overnight business trip to Colorado. The timing was impeccable. One night to think things over, to imagine a world without a sun. That night he called me from his hotel in Denver, saying there was something he wanted to talk about when he got back. Code word: "Something."

"Have a safe trip home," I said. "Darling." I hung up and made reservations at the Lark Creek Inn in Marin. Chef Bradley Ogden, home of the eighteen-dollar appetizer. That night I sleep fitfully. I am what my mother used to call overexcited. I think about what if the plane crashes and he never gets to ask me. I will tell people he did, I decide.

I felt extremely focused.

The next day, Tuesday. He comes home around four in the afternoon. He actually runs to the kitchen, to find me.

He loves me, I am thinking. Also: Baby, you are going DOWN.

We embrace. His skin feels cool, as though he had flown home without the airplane. He has on a thick moss-green plaid flannel shirt which he has purchased in Santa Fe, probably in a Western store with a wooden Indian outside. It soothed him, buying that shirt. I can see that.

At six we dress for dinner in silence. I watch him. And when I see him pull his gray suit out of the armoire, I know. It's not his best suit, but it's my favorite. Single-breasted. With the suit, he puts on his black merino-wool sweater. Another clue. A simple shirt would've been one thing. Or a black knit tee. The black tee would say, I'm sporty but not serious. It would say, I know how to wear a tee shirt with a suit, I'm a good catch. Try and catch me. The merino sweater has a collar and three neat buttons. It says, I'm caught. And I'm taking it like a man.

I wear a black sheer-paneled skirt and a long knit jacket from my first trip to Paris. Black hose, black heels. I put on my earrings with my eyes still on him. I hook the wire through the hole, blind.

We drive across the Golden Gate Bridge without speaking. Black Saab, top down. I'm wearing a velvet hat and dark sunglasses. We are listening to the jazz station. This would make a good commercial, is what I'm thinking. Also I am wondering how I am going to live if he doesn't ask. We would have to break up immediately, tonight. This instant. My mind flips back and forth, a fish on the deck.

We arrive and valets grab the keys from his hand, open doors. Once inside, we are quickly seated. Time is speeding up, not slowing down as in emergencies. Table in the corner. The perfect table, I am thinking. Now he has to ask me. The center tables are ambiguous. The corner tables are definite.

They pour the wine. He tastes it, nodding. He orders our food; I let him. I can't feel my legs.

There is a long, flesh-eating silence. And then he says, "So what should we do?" "About what?" I ask, caressing the stem of my glass. I am going to make this as difficult as possible for him, I don't know why. There seem to be bonus points involved.

"You know what," he says. He has a wide, strange smile, like a maniac who is about to reveal that he is strapped full of Plastique explosives.

"What what?" I ask.

Now I am smiling too. I can't help it.

"Maybe we should get engaged." He says it.

"Maybe we should," I say.

I take a long slow sip of wine. I have seen our cat, Cow Kitty, whom we call the Cow for short, do this to bees. First he stuns them and then he watches them die.

"Do I have to do it now?" Michael asks. He sees the waiter headed toward us, a large tray held expertly overhead. He has ordered the Yankee Flatiron Pot Roast, with baby vegetables. $28.95. "Can't we wait until after?" he says.

"No. You have to ask me now," I say. The pot roast is an incentive, making sure it's hot when he eats it. I'll get this out of the way, he's thinking, and then there will be pot roast.

"Will you marry me?" he says.

"Yes," I say.

We kiss. People around us continue to eat. It seems there should be something else, but there isn't. It's just a question, after all. Five words, including the answer. The pot roast arrives and he eats it all. I barely touch my cod; it is impossibly pale. I can see the plate through it. It occurs to me that I may be dreaming. I pinch my arm.

"What are you smiling at?" he asks.

"Nothing," I say. I'm awake, I don't say.

I always thought I would cry, but I don't. I laugh.

Later we get on the speaker phone and call my mother, who lives in Carmel with my stepfather, Don. She whoops.

It's difficult not to feel insulted. We finally found a buyer for the Edsel.

Recenzii

"For laugh-out-loud humor, Otherwise Engaged takes the cake." --USA Today

"Bitchy, bold, and brilliant." --Mademoiselle

"A darkly comic novel.... Finnamore also captures tender and even touching moments that illuminate this couple's relationship--and keep you rooting for them. But mostly she keeps you laughing. A great shower gift for the stressed-out June bride-to-be."--Newsday

"So funny and charming and smart. I felt bitter that someone else got to write it."--Anne Lamott, author of Traveling Mercies

"Bitchy, bold, and brilliant." --Mademoiselle

"A darkly comic novel.... Finnamore also captures tender and even touching moments that illuminate this couple's relationship--and keep you rooting for them. But mostly she keeps you laughing. A great shower gift for the stressed-out June bride-to-be."--Newsday

"So funny and charming and smart. I felt bitter that someone else got to write it."--Anne Lamott, author of Traveling Mercies

Descriere

Uproarious, insightful, and tender, "Otherwise Engaged" dashes our soap-bubble fantasies of weddings in favor of a hilariously realistic walk to the altar. "A great shower gift for the stressed-out June bride-to-be."--"Newsday."