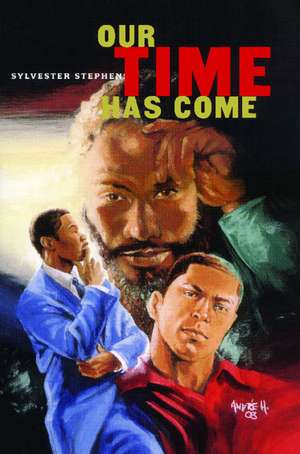

Our Time Has Come

Autor Sylvester Stephensen Limba Engleză Paperback – 26 oct 2004

In a dazzling display of political insight and masterful storytelling, Sylvester Stephens presents a new novel about what has been wrong throughout America's past—and what can be made right in its future.

Solomon Chambers is born in Saginaw, Michigan, in 1940. His parents and his uncle moved to Michigan from Mississippi years earlier, hoping to avoid the racism of their home state. Solomon eventually becomes a lawyer, and when his uncle is murdered in Mississippi he serves as a witness for the prosecution—and has his first real brush with the reality of racism. Later, in the year 2007, Affirmative Action and the Voting Rights Acts are abolished. When African Americans charge the United States government with violating their constitutional rights, Solomon is called to try the most significant case of his career, and one of the most important in history.

Full of powerful political commentary and dramatic narrative, Our Time Has Come is the inspiring story of a man who must confront himself and his own history—and fight for a just future that can heal the pains of a violent past.

Preț: 136.69 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 205

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.16€ • 28.40$ • 21.97£

26.16€ • 28.40$ • 21.97£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 02-16 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781593090265

ISBN-10: 1593090269

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.45 kg

Ediția:04000

Editura: Strebor Books

Colecția Strebor Books

ISBN-10: 1593090269

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.45 kg

Ediția:04000

Editura: Strebor Books

Colecția Strebor Books

Notă biografică

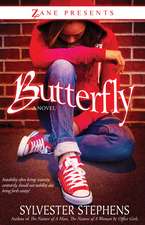

Sylvester Stephens is an author and playwright who performs motivational speaking engagements to motivate youths and encourage literary awareness. His books include Butterfly, Our Time Has Come, The Nature of a Man, The Nature of a Woman, and The Office Girls. He lives in Atlanta, Georgia.

Extras

Chapter One

SAGINAW, MICHIGAN, 2008

Every family has a story. A chronology of time, where names and people in the history of that family serve as a vessel from the past to the present. This is the story of my family. A story about the prophecy of a man named Alexander Chambers, told through the hearts and souls of his children. A story that tells of three generations to fulfill one prophecy. The first generation was given the prophecy, the second generation interpreted the prophecy, and the third generation fulfilled the prophecy. I am the fourth generation of the Chambers legacy, and though my father Solomon Chambers would fulfill the prophecy, I am blessed with revealing the prophecy to you.

My great-grandfather, Alexander Chambers, was born in a place called Derma County, Mississippi, in 1855. He was an only child, and a slave. He was college-educated, and not accepted very well by white people because of it. He met my great-grandmother Annie Mae while they were children growing up on the West Plantation in Derma County, Mississippi. After the Emancipation Proclamation, slavery was abolished, and Negro people were freed. However, my great-grandparents continued to work on the West Plantation. They eventually married and had one child, a son they would name Isaiah, my grandfather. He met and wedded my grandmother, Orabell, whom I loved with all of my heart. They, too, were blessed with only one child, Solomon, my father. We are generations of ones, for I, too, am an only child.

My great-grandfather Alexander decided his family would not be just another colored family satisfied with being free on paper, and not free in life. He wanted his family to be prideful, and understand that freedom is given to all men at birth. Great-grandfather Alexander believed that his son Isaiah had the hands of God upon him, and he was destined for greatness.

My great-grandfather created a book to chronicle our family's history. He said it would be our family Bible. He wrote the title of our family Bible: Our Time Has Come! Our Time Has Come originated from his inspiration that his family would one day overcome the manacles of slavery, and rise to the pinnacle of humanity. He started the Chambers Bible with the first verse. Each generation was to incorporate his, or her, new verse to pass on to the next generation to come. And these are the words of our family Bible:

"Our Time Has Come"

Alexander and Annie Mae Chambers -- 1902

The dawning of a new millennium, sing songs of freedom, Our Time Has

Come. Our God send signs it's time for unity, this is our destiny,

Our Time Has Come.

Isaiah and Orabell Chambers -- 1939

Today begins the day, thought never be, when we rise, in unity, One God,

One Love. Our voices be the sound of victory, when we, stand proud

and sing, Our Time Has Come!

Solomon and Sunshine Chambers -- ????

These are the inspirational words of my great-grandfather, and my grandfather. But here it is in the year of our Lord 2008, and my father has yet to add his generation's verse to the family's Bible. He is a sixty-eight-year-old man and his opportunity to pass the Bible to me with his verse inscribed, is rapidly decreasing.

My father does not believe in the prophecy as my grandfather, and great-grandfather. He believes in today, and making the most of it. He wants his legacy to be remembered for what he has done as a scholar and professional, and not as a martyr, or activist. He does not believe in the struggle for the advancement of Black people. He believes that every man should make his own way through the means of education; regardless of the circumstances. He believes that success is colorblind. All that he sees is determination and hard work. Any circumstance can be overcome by determination and hard work. I adamantly disagree with my father. I believe that success, first of all, is a relative word. I think that one can dream of success, but when one arrives at the reality, he has lost so much of himself that the passion for success has turned into a mere achievement.

My father has a lifetime of achievements: certificates, honorary degrees, memorials, foundations. If you can think of any outstanding award that is bestowed upon a human being, my father has one somewhere with his name on it. He is one of the most famous attorneys in the United States. His name alone is said to have settled cases without ever going into litigation. And yes, this man, is my father. A man of strong character, and resiliency, of course he has suffered as all men have suffered. But through his sufferings, he emerged a stronger and more determined man than he was before his crisis.

A "trailblazer" in the field of law for African-Americans who follow in his footsteps; a title he publicly denounces. He is called a paramount of an attorney not just for African-Americans, but for all Americans. When asked of his contributions to law, he humbly refers to Thurgood Marshall and says, "Without his contributions, there would be no place for my own." This man is my father.

At this hour, my father is doing what he has done his entire life; searching for the perfect solution to his current problem. This time the issue he faces is greater than any other he has faced in his life. For the issue is not about losing or winning a case. It is not about the prestige of his name, or his crafty courtroom tactics. It is not about awards, certificates, or foundations. It is about an issue he has eluded, and escaped for sixty-eight years. It is time for my father to relinquish his past, and embrace the present. The time has come for my father to face his ultimate nemesis: himself.

• • •

WASHINGTON, D.C., 2008

"As I stand here before you, Lord, my mind reflects upon the past sixty-eight years of my life. And I wonder why destiny has led me to this place, and this time. I am an old man, Lord. If You had given me this task twenty years ago, I would have been more than able to fulfill it. But tonight, what good am I to you?

"I have spent the last year working, and trying to do Your will but I am tired, Lord. I don't know if my old feebly body can hold on until tomorrow.

"But I do know one thing, Jesus. When I leave this courtroom tomorrow, one way or the other, I won't have to worry about ever coming back into another one again in my life. I'm going to have to rest these old bones.

"Well, Lord, I'm almost through praying. My knees hurt so bad I can hardly stand up. Wait a minute, Lord. I've changed my mind. I'm not quite through yet. I wonder how my father would feel if he knew that his only son had grown up to be in this dubious position. My guess would be very afraid. Afraid that I may die in the same manner in which he died. Could You tell him I'm sorry, Lord? Aw, don't worry about it. As old as I feel, I may be able to tell him personally in a day or two.

"Lord, my mother always said that you won't put any more on us than we can handle. How much more do You think I have left, Lord? Give me my strength for one more day, Lord; just like you did Sampson. Please, Lord, just one more day." Solomon continued to stay on his knees as he held the back of the pew in front of him for support. He said, "Amen," to conclude his prayer, and looked up to see an old man entering the rear of the courtroom.

"I'm sorry, sir, this courtroom is not open to the public. You are not

supposed to be in here. This is a top security building. How did you get in here, anyway?" Solomon asked.

"That's the one good thang 'bout bein' a broke-down old man. Nobody ever pay you no 'tention. 'Course they don't pay you no 'tention when you need it, too. I walked up to that do' and walked straight through it, and ain't nobody said one word to me. When you old like this, son, you 'come invisible." The old man laughed.

"I know the feeling of being old," Solomon said.

"Why, you just a baby, Solomon." The old man laughed again.

"You know my name?" Solomon asked.

"Who don't know Solomon Chambers, the modern-day Moses," the old man whispered. "We need you, son. We need you bad."

"What can one man do against the powers that be?" Solomon asked.

"You ain't just one man. You God's man, and like the good book say, if God be fo' you, who can be against you? If God is in you, son, then you the powuh that be. Who can stand against you?" the old man said with his chest stuck out and shoulders pulled back.

"The United States government!" Solomon sighed.

The old man laid his cane to his side, and slid onto one of the benches.

"Let me tell you somethin', son. Sixty-eight years ago I was convicted of robbin' somebody. I was only sixteen years old. They stuck me in a prison with old overgrown men. I was only a boy. Sixteen years old! And they stuck me in that hole and let me rot for sixty-eight long years. I don't have no family. I don't have no friends. I don't have no nothin'!

"They only let me out so I can die, and they won't have to foot the bill. My whole life is gone. Just wasted! You know I done asked God a million times to just let me die. But He wouldn't. As a matter of fact, I ain't never been sick a day in my life until they let me out of jail. And even now, my body ailin' me, but I ain't been down sick. Who say God ain't got no sense of humor, huhn?" The old man laughed.

"Well, thank Jesus you're a free man now," Solomon said.

"Free? What make me free? I ain't got no place to live. I ain't got nobody to love, and I ain't got nobody to love me. I ain't even got nowhere to die. My freedom was taken from me when I was sixteen. I'm an eighty-four-year-old man; the only freedom I got waitin' for me is death. And I can't wait for it to come neitha! I spent my last cent, and probably my last breath comin' all the way up here to talk to you about how important this trial is, Solomon, and I thank God I did."

"I know that this is a high-profile trial. But the bottom line for me is that I see this as yet another trial that I must bring to a just and strategic conclusion."

"Is that why you was prayin' to the Lord? 'cause this is just another trial?"

"I was praying to the Lord because I need him."

"You don't have to worry about the Lord helpin' you, son! You know He gon' do that. You gotta help yo'self!"

Solomon sat up, and tried to stand. It took him a while, but he eventually completed the task. He grabbed his briefcase and thanked the old man for the words of inspiration.

"Thank you, sir, for the words of confidence. I am curious about one thing, sir," Solomon said. "How in the world did you possibly get sixty-eight years in prison for robbery?"

"Hell, I sat in prison for two years befo' they even stuck a charge on me."

"No trial, no conviction, no due process?" Solomon asked.

"Due process? In 1940? In Mississippi? I was happy fuh due life!"

"Did you come all the way up here to tell me that story?"

"No, son, that ain't the story."

"Well, why did you travel all of this way to talk to me?"

"I came to tell you about a man. But befo' I tell you 'bout anybody else, do you know who you are? I ain't talkin' 'bout you bein' no lawyer. Do you know who you is inside? If not, you need to think. Think, son! Before I go any furtha," the old man said.

• • •

DERMA COUNTY, MISSISSIPPI 1935

It was a small county where the colored people made up seventy-two percent of the population. However, the imbalanced number of white people were the beneficiaries of wealth, and power from prior generations. Most of the white people were the children of former slave owners, while most of the colored people were children of former slaves.

The white families had spacious plantation homes, with long driveways that started so far from the house, it was impossible to see the house from the road. There was a social and economic status that was commonplace for mostly all of the white people.

Derma was a rich county, and there were only a few white families who were not wealthy, or financially established. Those few lived in small houses, and worked for the wealthy whites. They also socialized with coloreds, more than whites. The coloreds still called them "Ma'am" and "Sir" and entered through the rear of their homes. They had to respect the color barrier, because the laws of Jim Crow were in full effect.

Jim Crow Laws were the laws formed by Southern states to fight the federal laws incorporated by the Emancipation Proclamation. It kept the spirit of the old South alive.

The colored people lived in large groups in small houses, only a few feet apart. Two or three generations often shared one- or two-bedroom cabins. There were some colored people who moved far into the woods where land had not been claimed to create breathing room for their families. These few families often broke the mold of the poverty-stricken coloreds and became educated and financially stable themselves.

One of those families was the Chambers family, Alexander and Annie Mae Chambers. Alexander was college-educated and worked as a teacher, which was the most prestigious profession for a colored man in Derma County, outside of the clergy. Annie Mae worked on the West Plantation as a maid. She and Alexander were raised together on the West Plantation.

Alexander left Mississippi and went to college up north in Pennsylvania. There he witnessed colored people who were respected and accepted in everyday society. He met a young minister who would later move to Mississippi and hire Annie Mae from the West Plantation. When he returned to Mississippi he could no longer accept the blatant discrimination against colored people without voicing his opinion.

Alexander and Annie were married in 1883 and had their only child, Isaiah, eighteen years later in 1901. Alexander taught Isaiah that he was the equal to any man on this planet: colored, white, rich, or poor. Alexander instilled in his son that the only way to fight discrimination was through education. He made Isaiah believe that an education may not stop some doors from closing in your face, but it can sure open a lot of doors that have always been locked. Annie Mae, on the other hand, taught Isaiah how to be an educated man in Derma County without ending up with his neck at the end of a rope.

In 1911, Alexander's inability to adapt to Mississippi's growing defiance of the advancement of colored people caused him to rally colored families together and speak out against their mistreatment from whites. He told them to save money and buy plenty of land, as he had done, and farm it to support themselves. He told them to learn to depend upon themselves for survival, and not white men.

Alexander explained that coloreds in Derma County outnumbered whites three to one, and they should be a part of the decision-making process. He was met with angry and violent resistance from the white politicians.

On Christmas Eve of that same year, Alexander went out to fetch Christmas dinner for his family, and never returned. Isaiah and one of his friends found his body two days later hanging from a tree in the woods. They dragged his body on a blanket four miles to their house. Ironically, the boy who helped him carry his father's body from the woods was a white boy named John, who lived on the next acre of land with his mother. Isaiah had nothing to give the boy to repay him for his kindness. So he made him a necklace out of the twine used to hang his father. The boy may not have realized where the material to make the necklace came from, but nevertheless, being an impoverished child himself, he was happy to receive it.

Annie Mae was devastated, and never mentally recovered from Alexander's death. Later, her land was confiscated and all that remained for her to support herself and Isaiah was her job working as a maid; a job most colored women sought for employment. But Annie Mae had become accustomed to Alexander's income from farming their land. The land was gone, and the income went with it. Her strength for living was to protect and provide for her son. Isaiah, at the age of ten, suddenly became the man of the house.

Annie Mae raised Isaiah to be a God-fearing man, to believe in God's book, and not man's book. Isaiah, although having been raised by Alexander for only ten short years, was truly his father's son, for he decided to believe in both.

Isaiah grew up to be a strong-willed, but gentle man. His father's murder left an indelible mark on his heart and soul. Like his father, he, too, went up North to attend college. He also witnessed the acceptance of colored people in society, and the conspicuous difference between Negroes in the North, and coloreds in the South.

After college, Isaiah went back to Mississippi to take care of his mother and the land his mother's bossman had purchased for her while he was away. He did not want his mother to lose her land again to the manipulating scoundrels who had stolen their land after his father's death.

He became a schoolteacher and a leader in the colored community. He was respected by coloreds and whites. He had an even temper, and was respectful to every person he met.

In 1934, Annie Mae was stricken with a severe case of pneumonia and died peacefully in her sleep. On her death bed, she revealed to Isaiah certain secrets she had kept hidden from him. The news paralyzed Isaiah's emotions and, after Annie Mae was buried, he became more involved in the church.

A year later Isaiah met a young lady by the name of Orabell Moore in church, where he taught Sunday School. Most people said he had missed his calling to be a preacher. Isaiah started to invite Orabell to church functions, and they fell in love and wanted to be married. He knew that before they discussed marriage any further he had to discuss it with her parents, whom he had never met personally. Mrs. Moore was the sweetest old lady you'd ever find, but Mr. Moore was stubborn, and settled in his ways. He was notorious for carrying a shotgun named Susie and shooting it at people. Though his reputation preceded him, no one ever found proof that he had actually shot someone.

Mr. Moore was a balding, white-haired old man with light skin and sharp, gray eyes. His eyebrows and mustache matched the white color of the hair on the top of his head. He was a small man who spoke fast with a high-pitched voice. He often stuttered, which made it difficult to understand him sometimes. He was in a hurry to get things done; even when there was nothing to do. He wore baggy pants held up by suspenders and corduroy shirts with a white undershirt even in the midst of summer. And he capped it off with a gray and black evening hat. He was a religious man, with the tongue and temper of the devil, who often spoke before he thought.

Mrs. Moore was dark-skinned with long white hair that she kept plaited in one big ball. She wore the long thick skirts that tied around the waist. Her shoes were black with buckles on top. She was the exact opposite of her husband. She was humble and courteous and often resolved issues instead of create them. Mrs. Moore had long patience and tough skin. But when her patience ran out, she could be as vicious as anyone.

The Moores lived back in the woods on land founded and owned by Mr. Moore's father. As most black men in those days, Mr. Moore's father died young, and he had to take over being the man of the house. After he and Mrs. Moore were married they lived together in the house with his mother until her death in 1889. Mr. Moore farmed the land until his body would no longer allow him.

Mr. Moore was proud of his house and his land. His house was huge with a grand porch. The driveway was long like the white folks' driveway and led to the front door of the house. The house sat back far from the road with trees in the yard that hid most of its view until you were almost directly in front of it. There were six stairs leading to the porch making the house appear to be sitting high off of the ground. The porch had two rocking chairs and a porch swing. You entered through the front door and into the living room. The walls were painted with bright colors. The floor was hardwood and shiny. The furniture was antique but in new condition. The kitchen was huge and green. It had a green floor, green cabinets, green walls, and white sink. Upstairs there were five bedrooms. The Moores occupied one, their daughter Orabell and son Stanford occupied one apiece, and the other two were for occasional visitors.

Isaiah had taken notes on all of the habits, beliefs and ideas of the Moore family, and he was going to use them to his advantage when he was courageous enough to go to the Moores and ask for their daughter's hand in marriage.

Mr. Moore refused to allow Orabell to court any man, and she was twenty years old. In that day, an old hag. Isaiah felt that he could convince Mr. Moore to change his mind. He was nervous and perspiring when he walked up the porch stairs to the Moores' home. They looked at him strangely when he stood before them but did not say a word. Finally he found the courage to speak.

"How are you doing this evening, Mr. Moore, Mrs. Moore?" Isaiah asked. "Wonderful evening, isn't it?"

Isaiah was about five feet, ten inches tall, fair-skinned, with dark black curly hair. He had very broad shoulders with light brown eyes, and spoke softly and articulately. He had finally gotten up the nerve to ask for his girlfriend's hand in marriage. A girlfriend whose parents had no idea she was dating.

"It sho' is, son. What might you be payin' us a visit fa tonight?" Mrs. Moore asked.

"Ya look too old to be runnin' around wit my boy, so ya must be comin' fa somethin' else. I hope it ain't fa my gal. Tell me dat ain't why you here, son?" Mr. Moore snapped.

"Well sir, here is the situation. I want to explain this properly so that you won't get the wrong understanding of my intention. I've been a little sweet on your daughter. Yes, sir, I'll admit that to you face to face, like a man, and get that out of the way. I know I am talking a little fast, sir, but that's because I'm nervous...not shady like I'm trying to be crooked, sir, but

nervous...nervous. OK, sir, here it is! I am a schoolhouse teacher, and a Sunday School teacher. I give my tithes every Sunday. Even more than the ten percent the Bible tells us to give. I...I...I...I don't drink, I don't run around chasing after a bunch of different women...I don't have any children running around here either, sir! You can believe that straight from the horse's mouth," Isaiah rambled nervously.

"Hey, boy! You tryin' ta court me, or my daughta?" Mr. Moore asked.

"I'm sorry, sir. I want your daughter, sir," Isaiah said calmly.

"AHA! I knew that's all you wonted!" Mr. Moore screamed.

"No! No, sir! I don't want anything...well, I want Orabell, but that's it!"

"Henry, stop it! You 'bout to scare that boy halfway to death." Mrs. Moore laughed.

"You sure are, sir; you're about to scare that boy halfway to death," Isaiah cried.

"See what you done did, Henry? That boy done fuhgot who he is," Mrs. Moore whispered.

"Mr. Moore, please listen to me, sir. I plan on taking care of your daughter. I have a big house that I built, outside of the West Plantation; I have just as much land as any white man in Derma County. If we ever needed money I could always sell my land so that Orabell would never want for anything," Isaiah said.

"You might not be shady, but you sho' sneaky. You think we don't know 'bout you creepin' round here wit' Orabell?" Mr. Moore asked. "Hadn't been fuh my wife, and me bein' a Christian, me and ol' Susie woulda came and paid you a visit, boy!"

"Mr. Moore, I stand to tell you that yes, I have been courting your daughter, Orabell, but only to church picnics, and revivals. I am not tied up, nor have I ever met anyone named Susie."

"Boy, are you sho' you from Derma County?" Henry asked. "Susie is my shotgun!" Mr. Moore said, erupting in a very loud laugh.

"Oh," Isaiah said, feeling embarrassed.

"Say what you gotta say, son. I gotta get ready fa bed," Mr. Moore mumbled.

"Well, Mr. Moore, all that I have to say is that I love your daughter, and I came over here to ask you for her hand in marriage."

"Son, if I'm right, and I figur' I am, you 'bout twice my daughta age, ain't ya?" Mr. Moore asked.

"No, sir. I am approximately fourteen years older than Orabell, but that doesn't matter."

"The hell it don't!" Mr. Moore shouted. "You done had women, grown women, and my baby ain't had no exper'ince wit' no grown man...ha' she?"

"Oh no, sir! No! No! No! No!"

Mr. Moore looked at Isaiah out of the corner of his eye, as if to let him know that he was watching him to see if he was lying or not.

"We gon' have to pray on it, son. Like my husband say, you near 'bout twice huh age. She don't know nothin' 'bout bein' wit' a man, 'cause I ain't taught huh yet." Mrs. Moore smiled.

"Ma'am, I don't mean any disrespect, but what do you think you can teach her about me, if you don't know me?"

"I don't aim to teach huh nothin' 'bout you, son. She might not even end up wit' you. I'll teach huh what she need ta look out fa in any man. You seem like a good enough fella. You just too old fa my baby. I don't think huh daddy too happy 'bout dis either."

"Hell naw, I ain't happy!"

"Stop all dat cussin', Henry!"

"Well, dis boy could be a crook, a bank robba', anythang! Hell, we don't know!" Mr. Moore said, pointing at Isaiah. "Son, I had my baby when I was almost sixty years old. She is the most preshus thang I got. I can't just let anybody walk up here and take her off."

"I understand what you're saying Mr. Moore," Isaiah said, walking backwards down the stairs. "I think it's about time for me to leave, but 'm happy to have met you and your beautiful wife, and I wish you both a lovely evening."

"Boy, you sho' know how to suck up, don't ya?" Mr. Moore laughed.

"Henry, leave dat boy alone! Thank you fuh stoppin' by, Isiaer," Mrs. Moore said.

"You're welcome," Isaiah answered, nodding his head and holding up his hat.

Isaiah walked off of the porch, and down the driveway to his car. Mr. and Mrs. Moore immediately began to discuss their opinion of his visit.

"I'm gon' tell you sumthin', Cornelia; dat is da fanciest talkin' nigga' I have evuh seen in my life. Talk like a ol' fashion woman. Ain't no man dat good, and he a fool if he think I believe one word of dat mess."

"Well, I believe him. He sound like he was tellin' da troof."

"Lissen at you, ol' woman. A young man come 'round here talkin' fancy to ya, and ya ready to just give ya daughta off to him. Don't dat beat ev'rythang?"

"Say what you wont 'bout his age, but dat's a good man, and ya know it. You just don't wanna give ya baby up."

"You dam' right I don't, and I ain't neitha!"

"You gon' have to one day, if ya wont to, or not."

"Where O'Bell at? Get out here, O'Bell!" Mr. Moore yelled.

Mrs. Moore stood up and yelled through the screen door.

"O'Bell, come see what ya daddy wont!"

Orabell took her time, but eventually she stepped through the screen door to see what her father wanted. Orabell was stunningly beautiful. Dark, smooth skin. Naturally wavy hair, that trickled down her back. An hourglass figure, which displayed every curve on her body, even in the loose-fitting dress she wore. Although she was quite petite in stature, her presence was amazingly noticeable.

"Yes, Daddy?" Orabell asked.

"Ya new beau came ovuh here askin' fuh ya hand in marriage. Nah you wanna tell me what dat's all about?"

"What you talkin' 'bout, Daddy?"

"You know what I'm talkin' 'bout, guhl. Don't talk to me stupid! I'm talkin' 'bout dis grown man comin' up to my house askin' fuh ya hand in marriage. Where you meet dis man? And what make you think I'm gon' let you run off wit' him?"

"Daddy, I ain't runnin' off with nobody. Isaiah and me, we go to church together. He taught me how to read good, and not like how they taught us in school. He's a good man, Daddy, and I love him...I just love him."

"You love him? What you know 'bout love, O'Bell? What make you think dis man gon' make a good husban'?"

"He treat me special. He always askin' how I'm doin', or what can he do to make me happy." Orabell sobbed. "Sometime, Daddy, I wonder why God even let me be born. Think about it, Daddy, what do I have to live for? All I do is take care of you, and Mama. I ain't complainin' 'bout that, but who am I goin' to live for when y'all ain't here no mo'? What's gon' happen to me when I have to live my life all by myself? You ever think about that, Daddy? I don't care how old Isaiah is, he love me for me. And I'm goin' to marry him if you say yes, or if you say no. Now I love you and Mama with all my heart, and I ain't never in my life stepped against nothin' y'all ever told me to do. But I ain't goin' to let this man get away from me," Orabell said with tears in her eyes.

"Cornelia, you ain't gon' say nothin' to dis guhl, talkin' crazy like dis?" Henry shouted.

"It ain't my place to say no mo', Henry, and yours neitha. That guhl know if she love dat man or not. She right, she gon' have to live huh own life. And if she know she love dat man, and dat man love huh, Henry...leave huh be."

"I said what I had to say 'bout it. Until I get to know dis man, ain't nobody marryin' nobody! So get dat notion out of ya head right now! Ya hear me?"

"Yes, Daddy." Orabell sighed.

Mrs. Moore wrapped her arms around Orabell and whispered, "Ev'rythang gon' be all right, baby. Go on in da house and get ya some rest."

"I know it will, Mama," Orabell whispered back. "Goodnight, Daddy."

"Goodnight, baby," Mr. Moore mumbled. "Hey! Come on ovuh here and give ma a kiss."

Orabell kissed Mr. Moore and told him she loved him.

"I love you too, baby. I hope you know I ain't tryin' to huht ya. I'm tryin' to pratect ya."

"I know, Daddy."

As Orabell started to walk back into the house Mr. Moore reached for her arm and stopped her. Orabell saw that her father was on the verge of crying, something she had never witnessed before, and she wiped his eyes.

"Baby, sometime it's hard to say goodbye to somethin' you love so much, but I guess holdin' on ain't gon' make thangs no betta. I guess it's time fa me to say goodbye and let go...goodbye, angel." Mr. Moore cried.

"Goodnight, Daddy." Orabell smiled.

At 4:00 A.M. the next morning, Orabell was awakened by cries from her mother. She quickly jumped out of bed and rushed to her mother's bedroom.

"What's wrong, Mama?"

"Yo' daddy, child, yo daddy ain't movin'! Help me wake him up!"

Orabell shook Mr. Moore, and cried along with her mother. Her younger brother, Stanford, rushed into the bedroom bewildered and hysterical. After unsuccessfully waking Mr. Moore, Orabell shouted for Stanford to run and get Dr. George West. Most colored folks in Derma County didn't have telephones, and the Moores were among the many who didn't, so when there was a medical emergency their only communication for help was primarily through word of mouth. Dr. West was the only doctor in Derma County. A lot of people believed that the West family kept other doctors from practicing in Derma County because Dr. West wanted all of the business for himself. Which meant he treated his patients less than respectable. Especially the colored patients.

Mr. Moore was still alive when Stanford left for Dr. West. He was breathing weakly, and had no control over his body, but he was alive just the same. Stanford returned from Dr. West's house at 7:00 a.m., but Dr. West did not arrive at the Moores' house until 5:30 p.m. He apologized for the delay, saying he had prior plans to visit some friends for breakfast and lunch. Unfortunately, by the time he arrived Mr. Moore was dead.

"Excuse me, doctor, how long my daddy been dead?" Stanford asked.

"I reckon he ain't been dead no more'n an hour or so," Dr. West answered.

"Are you tellin' me my daddy might still be alive if you woulda got here when you was supposed to?" Orabell cried.

"Can't say yeah, can't say no, but what I can say is that he sho' is dead now, ain't he?" Dr. West snickered.

"How can you stand there wit' a man lyin' dead in front of you and laugh like that. Knowin' that you could have pro'bly saved his life?" Orabell screamed.

"I can stand here on my two feet," Dr. West snarled. "Nah, Cornelia, I know this is a sad time for you and yours, but don't let ya pretty little girl get herself in trouble talkin' back like that. Get her on outta here befo' I lose my patience and fuhget her daddy layin' up here dead."

"She just huht, Dr. West; don't pay no 'tention to huh," Mrs. Moore pleaded.

"I'm gon' pay plenty 'tention to her if she don't shut that black mouth and let me do my job," Dr. West said, then went back to discussing Henry. "Henry looks like he's in good shape for the night, but I advise you to round up some of these boys and get him outta here by tomorrow morning. It's gon' be a scorcha, and that heat will rot Henry up quicker than a lit match light to a gallon of gas. I guess my job here is done. Cornelia, do you have some of ya famous cool lemonade?"

"Yessuh, Dr. West. I'll go fetch ya some," Mrs. Moore said.

"I'll go get it, Mama; you just sit down and cool off." Orabell smiled.

Dr. West stared at Orabell and shouted as she was going into the kitchen, "I betta not see no suds floatin' round my glass. You look too eager to be fetchin' some lemonade," alluding to the possibility of Orabell spitting in his drink.

Orabell went into the kitchen and fixed Dr. West a glass of lemonade, then took it back to him. Dr. West reached into his coat pocket and took out a handkerchief. He carefully wiped the mouth of the glass before he took a drink.

Meanwhile, Isaiah was walking up the driveway and noticed Dr. West's automobile. Orabell saw him and went outside to meet him.

"I'm so happy to see you, Isaiah." Orabell sighed.

"Hey, Orabell, what's going on, who's sick?" Isaiah asked.

"Nobody sick no more. My daddy died today."

"What happened?"

0 "When mama woke up this morning she tried to wake my daddy up, but she couldn't. But he was still alive, Isaiah. Stanford went for Dr. West at five-thirty in the mo'ning, but he didn't get here until five o' clock this evening. He had all day to help my daddy, but he had betta things to do like go eat wit' white folks."

"Orabell, talking that way is only going to bring on worry, and worry is going to bring on pain, so stop fretting over things you can't change and go take care of your mother. I'll see to Dr. West."

Orabell went back into the bedroom with her mother and dead father, while Isaiah pulled Stanford aside and took him into the living room with him.

"Good evening, Dr. West," Isaiah said.

"How do! What's yo' name again, boy? I know you that schoolteacher. You Annie Mae's boy, ain't ya?"

"Yessir, Annie Mae was my mother. But I haven't been a boy in nearly twenty years. I'm a grown man and I'd appreciate it very kindly if you would refer to man as such. Especially in front of the boy, sir."

"Henry ain't been dead a day, and you done came in and made yo'self right at home, ain't you, boy?" Dr. West laughed.

"As I told you, sir, if you are going to address me, I'd appreciate it if you would address me as a man. Especially in front of the boy!" Isaiah said firmly.

"Looka here, you done went out and got you a little education, and yo' britches done got too big for yo' own good, boy."

"Dr. West, this family needs to be alone. I am asking you to please leave so that they can get some peace and quiet, and get on with their family business of burying their dead."

Dr. West stood up and brushed off his hat. He placed the empty glass on the end table next to where he was sitting and told Isaiah, "You know what, boy, it ain't been too long ago when I coulda had you hung for shootin' off at the mouth like that. You niggahs don't appreciate how good you got it these days. I come all the way out here to check on ol' man Henry and all I get from you ungrateful niggahs is a bunch o' smart-mouth sassin'. Tell you what, the next time one of ya get sick, don't call me, ya hear?" Dr. West screamed angrily.

Stanford slowly raised his head and muffled, "Don't you worry 'bout dat, Dr. West. It don't do no good no way. 'cause ev'rytime you come 'round here seem like somebody dead when you leave."

Dr. West was enraged by Stanford's comment and took the backside of his hand and slapped him to the floor. Isaiah immediately grabbed Dr. West and slung him out of the screen door and onto the ground. Isaiah stood on the porch and angrily pointed his finger at Dr. West, who lay flat on his back looking upward.

"Now, Dr. West, I am sorry for losing my temper, but I just can't stand here and let you slap that boy around like that. I didn't mean to hurt you. Once again, I apologize, now you just calm down and I'll make this up to you."

"There's only one way you can make this up to me, and that's for me to see a rope around your neck, niggah! And I'm here to tell ya, that befo' they can put ol' Henry in the ground, they gon' have to dig another hole for you." Dr. West screamed. Then he jumped in his automobile and sped off with wheels spinning, and dirt flying.

"You all right, boy?" Isaiah asked.

"Yessir, I'm fine," Stanford answered. "That old man can't hurt me."

"Let's go check on your mother and sister to see how they're holding up."

Later that evening Mrs. Moore, Orabell, Stanford and Isaiah were all sitting around Mr. Moore's bedside. They were exhausted from the events of the day. They sat in silence until Mrs. Moore thanked Isaiah for helping them during their crisis. "I thank you for stayin' 'round here makin' sho' ev'rythang all right, Isaier."

"It's only fitting that in times like these, we reach out to one another as one family. As common as death is, ma'am, it is still something that you can never get used to experiencing. I'm going to pray for your family that God has mercy on you all."

"We gon' need Him, and all of ya prayers. I don't know what we gon' do 'bout Henry. Lookin' back, I know I shoulda been prepared for him leavin', but I saw Henry as a young man, and I just didn't think he would be leavin' no time soon."

"Don't you worry about Mr. Moore, ma'am. I will take care of all the burial business. We can bury him on my land. I have a nice pretty spread where Mr. Moore can rest. And no thing, or no one, will disturb him. I'll be by first thing in the morning to take care of everything. We can have service for him in a day or two. Once everyone has been notified of his death, and given an opportunity to see him off. Then we can put him to rest."

"It ain't nobody to be notified," Mrs. Moore said.

"Well, that settles that. I will have Mr. Moore resting by this time tomorrow."

"You a good man, Isaier. You don't even much know us and you helpin' us like this," Mrs. Moore whispered.

"I know, Orabell, and if she is hurting, then I am hurting, ma'am. And I can only start to feel better when I know for sure that she already feels better."

"Whoo-whee! That man gotta tongue like a snake; I see why you fell fuh him." Mrs. Moore laughed.

• • •

In the days to follow Isaiah arranged for Henry to be buried on his land. Meanwhile, Dr. West had organized a lynch mob which plotted to kill Isaiah for pushing him to the ground. The colored community was well aware of Dr. West and his mob so they carefully hid Isaiah until they felt the situation had boiled over.

Isaiah became impatient with running and hiding. It was not his nature to hide from anyone, and sitting back waiting for a man to track him down did not rest well with him. He decided to confront Dr. West face to face. He figured that if he was going to be killed, he'd rather die like a proud man, than a sniveling coward. Of course Dr. West didn't care how he died; he just wanted him dead.

Isaiah picked a Sunday afternoon when coloreds and whites would be uptown in the Square enjoying ice cream and hot dogs after church. The Square was an enclosed four-block business district, except for the streets leading into and out of this business district. In the center of the four enclosed streets was a park for social activities. Most small Southern towns had a Square and the same activities went on at almost all of them.

Isaiah figured that Dr. West would be more forgiving if he was in broad daylight in front of his church friends wearing a white suit, than on a dark night with his Klan friends, wearing a white sheet.

Orabell pleaded for him to stay hidden until Dr. West had cooled off. This was considered to be a manner of paying back your disrespectful dues. When a white person had been publicly disrespected by a colored person, in order for the colored person to re-establish himself in his humbled inferiority position and return to the public without the threat of violence, they would have to not show his or her face again until an appropriate amount of time had passed. This was to re-establish the superiority status for that white person in society.

Isaiah had not served that respectable length of time because Dr. West was as mad as ever. However, it was a gorgeous Sunday afternoon, church was over, and the Square was filled with good spirits. Isaiah almost felt guilty about confronting Dr. West with all of the jubilation on the Square. But he knew it was confront him now, or be confronted later, with a shotgun and a rope.

The white people were in the park were enjoying themselves, while the colored people were standing around in the streets enjoying themselves. Dr. West and his wife, Mamie, were walking from picnic table to picnic table communing with other groups of white people and didn't notice Isaiah walking directly toward them.

Isaiah walked up to Dr. West and Ms. Mamie and stood in front of them. A few colored and white people noticed him, but it was no big deal to see Isaiah talking to white people no matter where they were. Isaiah cleared his throat and began to speak to the Wests very nicely.

"How are you doing, sir? Lovely day isn't it, Ms. Mamie?" Isaiah said.

"Boy, you must be outta yo' niggah mind to be walkin' up to me like this in broadlight!" Dr. West whispered.

"Is everything all right, Isaiah?" Mamie cried.

"I'm sorry, Ms. Mamie; I didn't come here for any trouble. I came to apologize to Dr. West about a certain matter. I want it to be done with this afternoon, one way or the other."

"I don't know what matter you're referring to, but this is hardly the time for you to be walkin' up to my husband for any kinda matter. You know you know betta than that Isaiah, now gon'." Ms. Mamie shooed with her hands.

"Ms. Mamie, I'm afraid that if I don't get this settled right now, the next time I see your husband he'll be wearing a white sheet, instead of the clean white suit he has on." Isaiah smiled.

"I demand to know what Isaiah is talkin' about right now, George!"

"This nigga has completely lost his mind, darling," Dr. West said.

"Oh no, Ms. Mamie, I am in my right mind and your husband knows it. He and some of his hooded bandits are going to kill me first chance they get. It may as well be right here, and right now. Ain't that right, Dr. West?"

"You know daddy wouldn't stand fa nothin' like that, Isaiah, 'specially from George!"

"I don't know what this fool talkin' 'bout, Mamie!" Dr. West cried angrily.

"Let me tell you something; my husband is a good Christian man, and he wouldn't harm a fly. So go on over there with the otha culluds before I forget about how much yo' mama meant to me."

Isaiah leaned over to Dr. West and said, "You know what I'm talking about, don't you, Dr. West?"

Grinding his teeth, Dr. West walked up to Isaiah and said, "Get out of my face befo' I kill you right here and now, nigga!"

"It's too bad you couldn't hear what your Christian husband just said in my ear, Ms. Mamie. But then if you did, you'd only pretend you didn't hear him anyway, now wouldn't you, ma'am?"

Dr. West pulled away from his wife, grabbed Isaiah by his arms and whispered in his ear, "Consida yo'self dead, boy."

"I already have, that's why I'm here..." Isaiah whispered back, with anger in his voice, "....Boy!"

"Leave Isaiah be, before everybody start lookin', George," Mamie said.

Dr. West pulled out a cigar, and puffed the smoke in Isaiah's face.

"Come on, honey, let's go," Mamie added.

Mamie did not want to be the center of gossip, especially if it involved Isaiah and his family. Her father was Reverend Willingham, who was particularly fond of Isaiah because of his mother, Annie Mae. She was the Reverend's maid, and best friend for the last forty-two years of her life. He treated Annie Mae as if she was his family. He bought all of the land within a two-mile radius of her house, and gave it to her. He was at her side when she died, and prayed while her soul crossed over to the other side.

Reverend Willingham was born and raised in Pennsylvania. His wife, Annabelle, was born and raised in Mississippi in the old traditional ways. She died two years after they moved to Mississippi in 1892. He met her in Pennsylvania and they were married in 1868. Before she died, Annabelle often fantasized about her early childhood and how magnificent it was before the Civil War. After she was stricken with tuberculosis, the reverend decided to move his family back to Mississippi, thinking maybe they could find a miracle in her joy to return to her home. To their dismay, they did not.

Annie Mae was working at the West Plantation when Alexander convinced her to work for Reverend Willingham. The West Plantation did not want to let her go, but Reverend Willingham had a way of getting what he wanted, even from the West family. She took care of Annabelle, and made her feel comfortable up until the day she died. After that, Annie Mae helped raise Mamie until she was grown and married to Dr. West. Reverend Willingham was indebted, and shielded Annie Mae and her family from the everyday confrontations of bigotry. Even with the protection of the reverend, it was not enough to save Alexander. Annie Mae made sure that, what happened to her husband would not happen to her son. She armed him with information that would protect him from the people that could harm him most, and she befriended the only person who could destroy those people once they realized he had that information, Reverend Willingham.

Reverend Robert Willingham was the minister of the largest church in Derma County, and the son of Abolitionists from Pennsylvania. Reverend Willingham's father aided in the escape of many slaves to freedom, using the underground methods of communication between the slaves, and the freed colored people, helping a countless number of slaves to escape from the South to the North.

Because of his upbringing, Reverend Willingham always preached and practiced equality to all men in his church. He fought discrimination and prejudices throughout the state of Mississippi. His battles ended up as defeats most of the time, yet still, he never refused a single challenge. Unfortunately, he had no inkling that his greatest foes sat on his pews every Sunday morning. He foolishly believed that his congregation believed and practiced as he taught, but even his precious daughter Mamie grimaced at the thought of a colored man living as her equal. Mamie dared not to speak a word of this to Reverend Willingham for even at his old age, he would probably take a strap to her behind.

Reverend Willingham was also one of the wealthiest men in the United States; a quarter of his assets could dwarf the entire West fortune if he chose to invoke his estate from Pennsylvania. His father was a mogul who helped build the railroad system from the East Coast to the West Coast. His father also traded in international metal trading. He had one sibling, a brother who was killed in the Civil War so he was sole heir to the Willingham Estate. Reverend Willingham, however, lived a humbled life and provided his family with only the necessities. He wanted his family not to be dependent upon money, but upon God. The Willingham Estate was to be inherited by his grandchildren. When Dr. West's two children inherited the Reverend's estate that would make the West family one of the wealthiest families in the country as well.

Reverend Willingham was nearly eighty-two years old, and his health was fading fast. Certainly, it would only be a matter of time before he passed on. The West family knew the reverend's health could not sustain much longer. So they patiently waited for him to die. But if he knew of the hypocritical manner in which they ran their business and the county, it would definitely strike a fire in him. Reverend Willingham would use every cent of his estate to bring them to their knees. The last thing they wanted was to give him a reason for staying around a few more years. They remained his most faithful members, for as far as his eyes could see them. They patronized him by standing in his church and giving testimonies on how they want all of the coloreds to one day be treated the same as white folks. Clapping their hands in celebration and telling the Reverend he had brought forth a peaceful way of living to Derma County. But all the time they were praising his name to his face, they were the decaying scab that covered the sores of Derma County.

The Wests believed that niggas should always be niggas, and white folks should always be white folks, and the two shall therefore never mix.

Privately, they were suspected as being the leaders of the Derma County chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan members of Derma County were not just redneck bigots who wanted to keep the white race pure. The Klan realized that they could benefit from utilizing the resources of the colored man. They developed businesses on colored people's land, and allowed the colored people to work at these businesses to support themselves. They had plenty of work, for minimal wages, if there were any wages at all.

The West family owned nearly sixty-eight percent of the businesses in Derma County. They came of their wealth during old slave-trading days, and in the production of agriculture.

The Wests used their money and power to manipulate the political process, and intimidate the coloreds and poor whites into not voting. That was the way the small population of whites was capable of holding every political office in Derma County. They considered this to be the necessary means of keeping white folks, white, and niggas, niggas. And assuring that the two would never mix!

• • •

Isaiah and Orabell were married in early spring, 1937. Isaiah had become a quiet activist for the equality of colored people. He didn't want to create a negative situation between the whites and coloreds, because that would only worsen the condition for coloreds. He kept his information and his approach very subtle and tried to bring awareness to the eyes of both races. Whites, he tried to convince to assist in advancing the lives for coloreds, and coloreds he tried to convince to become unified, and self-sufficient. And to accept the belief that equality should be the manner in which all men live. Both races thought Isaiah's views were too radical and too progressive, and they rejected them with harsh criticism. Isaiah figured that if he could get them to conquer their fears, they would begin to co-exist in an equal society. First, he had to get them to understand their fears. One, the fear of losing superiority, and the other, the fear from the wrath of gaining equality. Despite the reluctance from the people of Derma County, Isaiah still tried to unite the races.

While Isaiah was crusading the causes for colored people, Orabell had become paranoid with the thought of her husband being lynched by a mob of white men. She begged Isaiah to stay home and try to start their own family. He tried to assure Orabell that there was nothing to fear, and she should stop worrying. But it is much easier said than done for a woman who loves a man the way that Orabell loved Isaiah.

"Orabell, you're too young to have such an old soul; why do you worry so much?"

"I can't help it. My whole life I've been carin' for folks, and I can't change that now."

"You don't have to change. Being kind has never been a bad thing. Just stop worrying about the things you can't change."

"What I'm s'pposed to do, Isaiah?" Orabell shouted. "You're stirrin' up mess every day wit' these white folks! I know one day you ain't gon' walk through that door; I just know it! Why can't you just be happy wit' me, and start ya own family instead of runnin' 'round tryin' to take care of every otha' colored fam'ly in Derma County?"

"See, baby, that's where we're both alike. You give of yourself to your family, because that's the way God made you. I give of myself to my fellow man because that's how God made me. Can't you understand what I'm saying?"

"But carin' for my family ain't gon' get me killed! I don't wont to be no widow. I wont a family! Children! I just...Isaiah, I just want us to have our own fam'ly, wit' our own children. And leave everybody else alone."

"Listen to me, Orabell, please! My mother and my father were both slaves. After they were freed, life was even harder for them. My father was hung from a tree like an animal, just because he wanted what was his...and that's freedom, baby! Don't you see, just because Lincoln signed that piece of paper, it didn't make us free? The only way that we're going to be free is if we fight for our freedom!"

"My mama and my daddy was slaves, too, Isaiah! But I don't see what that got to do wit' nothin'! This is your family right here. You and me! You the head of this family, and you need to start actin' like it!" Orabell screamed.

"I've always been the head of this family. You don't want for anything, Orabell."

"I wonts for you, Isaiah! Can't you see that? I wonts for you! All this land don't mean nothin' to me if you ain't here wit' it! You ain't even here enough for us to even make no babies!" Orabell cried, bursting into tears.

Isaiah pulled her to his chest, and wiped her eyes.

"No, baby, no. We don't have any children because it's just not time for us to have any children. Why would you say something like that?"

"Because, Isaiah, everybody we know got babies, but us!"

"So what?"

"So what's wrong wit' us?

"There's nothing wrong with us. All that I can say is that if God wants us to have children, we will have them. And if he doesn't...well, I suppose we won't. Right now, I know that we have each other, and that's all we need to worry about."

"You know you got me, Isaiah, but I'm not so sure I got you. Seem like everybody in this world got you, but me."

"Nobody has me, Orabell, but you and the Lord. And I have to do what the Lord tells me to do. So please, let me be your husband, and God's servant."

"I don't wanna come between you and your God, but I love you so much, and I don't wanna lose you."

"I'm not going anywhere until God calls me. And what makes you so sure he's going to call me first?" Isaiah joked, "Ol' Gabriel may be playing his trumpet for you, before he plays my tune."

"That will be fine by me." Orabell laughed. "'cause when I'm gone, you'll just be the one crying like a baby instead of me."

"You are full of yourself today, aren't you, lady?"

"Oh, I'm full o' myself every day, baby, every day!" Orabell laughed with him.

Isaiah did not want to cause his newlywed any additional stress, so he stayed home more often and helped with the issues that only concerned colored versus colored. Orabell was happy. She finally had the marriage, and the man, she wanted.

• • •

One Saturday morning, in the fall of 1937, a young colored man by the name of William Crowell was riding the railroad passenger train back to Michigan. The young man had returned home to Derma County to attend his mother's funeral. He was only supposed to be there for a few days, and he then get back up North.

His mother was laid to rest, and so was his business with Mississippi. William missed his family and friends, but he could live the rest of his life and never return to the sweltering climate of bigotry and discrimination that hovered over Mississippi.

Although William was born and raised in Derma County, he was distinctive in his appearance, and his dialect. He had straight, sandy brown hair. His eyes were green. He had very thin lips. An extremely tall man of six feet four inches, he spoke very articulately, and his skin resembled that of a white man. It was well known that William's father was indeed a white man, but unknown was his identity. William was often mistaken for being a white man himself. As he grew older in life when that situation occurred, he learned to deal with it. If it was beneficial to him to pose as a white man, he acted accordingly. If it was not to his benefit, he simply explained himself as being colored.

After completing college William moved up North to a small Midwestern town to work. At that time, jobs were difficult to come by, due to the Great Depression that began in 1929, the year William left Mississippi. The South still had the same jobs, paying the same wages for colored people, educated or not. Adding to the pressure was the scramble for so many colored people to occupy so few jobs. The North was in the middle on the industrial revolution and jobs were a little more plentiful than in the South.

The automobile industry had just begun its assembly boom, and cities in Michigan, particularly cities near Detroit, maintained a steady work flow. When William first arrived in Detroit he was intimidated by the progressive lifestyle, having grown up in such a rural area. He decided to go further north, and settled in the town of Saginaw. He had not returned to Mississippi since he had moved to Saginaw. This was his first visit back since he had left eight years earlier.

• • •

As William sat on the train he had just one regret on his visit back to Mississippi, and it was that he didn't get the opportunity to visit his lifelong friend, Isaiah, whom he affectionately referred to as Zay. The two grew up as best friends from spanking new babies. They were born a couple of days apart, and were inseparable until they both became grown men and went their different ways. They were alike in many ways, but when it came to patience, God must have given all of William's to Isaiah, because he had very little.

Both of their mothers were strong women who raised their sons to be strong, and ambitious young men. They taught their sons to fear God, and God only. And that righteousness takes precedence over self. That standing as an upright man regardless of the circumstances, will always keep wrong from climbing all over your back.

While William sat reminiscing about his youth, two attendants from the train approached him and questioned him on his seating. William was sitting in the very first coach, which was for white persons only. He tried to defuse the situation by offering to move to another coach. The attendants were about to allow William to move to one of the coaches in the rear, but the conductor demanded that he be removed from the train and escorted to the nearest law office. William thought the conductor's request was outrageous and for that instance he forgot that he was in the great state of Mississippi.

He asked the conductor to explain himself. The conductor returned William's question with a question. He wanted to know if William was white or colored. If he was white, and he could prove that somehow, he would be allowed to catch the next train heading north. If he could not, he would have to go to court for violating the Whites Only Law. William refused to answer the conductor's question. He was forcibly removed from the train and escorted to the Derma County Courthouse, which doubled as the post office. He was placed in a cell and held for the remainder of the weekend. He would have to wait for his trial on Monday morning when the honorable Judge Woodrow West, the older brother of Dr. George West, returned from his fishing trip.

The sheriff was also out of town, transferring an escaped prisoner back to Jackson. He would have to stay in Jackson until Wednesday as a witness against the escaped prisoner. The sheriff was so well known for hunting down escaped criminals in the state of Mississippi, other counties, including Hinds, would call on him for assistance.

On Monday morning William was brought before Judge West for indictment, then immediately following, his trial. He was given a court-appointed attorney who wouldn't even look him in the face. William tried to make conversation with the attorney but he wouldn't talk back.

"Good morning, sir. I'm glad to make your acquaintance," William spoke. He held out his hand to shake his hand, but the man ignored him and walked to the judge's bench. They talked and laughed for a minute or two, then the man returned back to their desk. The attorney opened up his briefcase and pulled out a newspaper and began to read while the judge asked William to stand.

William stood before Judge West believing the judge would understand that this had been a huge misunderstanding, and he could clear everything up with an explanation and a sincere apology. William was indicted, and his trial began before he was ever allowed an opportunity to speak. The judge quickly moved forward to the trial. William never had to move his feet, or utter a word. The matter of due process was being moved right along. The judge finally spoke to William to begin the process of the trial.

"Mr. Crowell?" the judge asked.

"Yes, sir," William answered.

"Mr. Crowell, can you read, and, or write? And can you understand white man's English?"

"Yes, sir, I can read, write, and speak very well, sir."

"Well then, Mr. Crowell, you have been charged with violating the state of Miss'ippi Whites Only Law. Mr. Crowell, you are also being charged fa conspirin' to impersonate a white man to therefore violate the Whites Only Law. Is there anythang you would like to say on yo' behalf?"

"May I discuss this with my attorney first, sir?" William asked.

"Go right ahead, help ya' self." The judge smiled.

William sat down next to his attorney and asked him to advise him on what to say. "I kinda need your help here, sit. What should I say to the judge?"

"If I was you, boy, I wouldn't be sayin' nothin' to the judge; I'd be prayin' to the Lord about now." The man smiled and looked back down at his newspaper.

"But you're my lawyer; aren't you going to defend me?"

The man stood up and said, "Judge West, he said he didn't do nothing wrong, and he wonts to go home. Oh, and Judge, we rest our case"

William looked at the lawyer in disbelief, then turned to the judge. "May I say something to the court, Your Honor?"

"Help ya' self, but make it quick," Judge West said hurriedly.

"Sir, I have not intentionally violated any law. I boarded the train and I sat where the porter directed me."

"Where you from, boy? I 'clare you talk betta than me, and lookin' at ya, I can't tell if you white, cullud, or Injian!" Judge West joked.

"I am from Derma County, sir. Born and raised. I reside in Saginaw, Michigan where I work every day and abide by the law."

"What you doin' down here?"

"I came to attend my mother's funeral. All that I am trying to do now is get on a train, and get myself back to work before they let me go."

"Well it ain't that easy, boy. You done committed a serious offense here. We can't have niggas tryin' to pass as white. If I let you get away wit' it, every light-shade nigga in Derma County would be tryin' to get away with it. And we can't have that!"

The courtroom was silent as the judge thumbed through some of William's paperwork. He looked up, and asked William about his family.

"Who's your kin, boy?"

"My mother was Ruthie Lee Crowell."

"What's ya daddy's name?"

"I never knew my father's name, sir," William said reluctantly.

"You mean ya mama don't know what's done been up in her?" Judge West laughed.

William was enraged with the insensitive comments said by the judge. Once again, for an instance, he forgot that he was in the state of Mississippi. He responded with a malicious and resentful attack against his white father.

"Yes, sir, my mother knew exactly who my father was. He was a white man who raped her, and left her pregnant. A man who never accepted responsibility for his child, nor did he accept the responsibility of stripping my mother of her dignity."

"Boy, you already in hot water. That water you sittin' in now, is only stove hot. But you about to make that water hell hot in a minute!" Judge West pointed at William. "Let's just get straight to the point: are you white or are you a nigga?"

William stood there carefully contemplating the words he wanted to say.

"Judge, as an American citizen I choose to call upon the fifth, fourteenth and fifteenth amendments to the Constitution and not answer that question until due process of the United States justice system has been fairly served in this courtroom."

"What the hell?" Judge West looked around with confusion. "I asked you a question: are you white, or are you a nigga?"

"Judge, at this time, as an American born citizen, I choose to call upon the fifth, fourteenth, and fifteenth amendments to the Constitution, and not answer that question until due process of the United States justice system has been fairly served in this courtroom."

"Well, at this time, smart ass, I find you guilty on both counts. I'm gon' read your sentence to the court," Judge West snarled.

Judge West jotted down quick notes, then adjusted his glasses to read the sentences.

"On the first count, I find the prisoner guilty of violating the Whites Only Law of the state of Miss'ippi, and I sentence you to five years imprisonment in Parchman State Penitentiary. On the second count, I find the prisoner guilty of conspiring to impersonate a white man, to enable hisself to commit a violation of the Whites Only Law of the state of Miss'ippi. For that charge I sentence the prisoner to five years imprisonment in Parchman State Penitentiary. These sentences are to run consecutively, startin' one week from this day. At this time, Mr. Crowell, yo' due process of the United States justice systum has been fairly served. And for the recuhd, down here we call it, Miss'ippi justice! Lock the prisoner up, and this here courtroom is adjourned!" The judge loudly sounded his gavel, and limped out of the courtroom.

Copyright © 2004 by Sylvester Stephens

SAGINAW, MICHIGAN, 2008

Every family has a story. A chronology of time, where names and people in the history of that family serve as a vessel from the past to the present. This is the story of my family. A story about the prophecy of a man named Alexander Chambers, told through the hearts and souls of his children. A story that tells of three generations to fulfill one prophecy. The first generation was given the prophecy, the second generation interpreted the prophecy, and the third generation fulfilled the prophecy. I am the fourth generation of the Chambers legacy, and though my father Solomon Chambers would fulfill the prophecy, I am blessed with revealing the prophecy to you.

My great-grandfather, Alexander Chambers, was born in a place called Derma County, Mississippi, in 1855. He was an only child, and a slave. He was college-educated, and not accepted very well by white people because of it. He met my great-grandmother Annie Mae while they were children growing up on the West Plantation in Derma County, Mississippi. After the Emancipation Proclamation, slavery was abolished, and Negro people were freed. However, my great-grandparents continued to work on the West Plantation. They eventually married and had one child, a son they would name Isaiah, my grandfather. He met and wedded my grandmother, Orabell, whom I loved with all of my heart. They, too, were blessed with only one child, Solomon, my father. We are generations of ones, for I, too, am an only child.

My great-grandfather Alexander decided his family would not be just another colored family satisfied with being free on paper, and not free in life. He wanted his family to be prideful, and understand that freedom is given to all men at birth. Great-grandfather Alexander believed that his son Isaiah had the hands of God upon him, and he was destined for greatness.

My great-grandfather created a book to chronicle our family's history. He said it would be our family Bible. He wrote the title of our family Bible: Our Time Has Come! Our Time Has Come originated from his inspiration that his family would one day overcome the manacles of slavery, and rise to the pinnacle of humanity. He started the Chambers Bible with the first verse. Each generation was to incorporate his, or her, new verse to pass on to the next generation to come. And these are the words of our family Bible:

"Our Time Has Come"

Alexander and Annie Mae Chambers -- 1902

The dawning of a new millennium, sing songs of freedom, Our Time Has

Come. Our God send signs it's time for unity, this is our destiny,

Our Time Has Come.

Isaiah and Orabell Chambers -- 1939

Today begins the day, thought never be, when we rise, in unity, One God,

One Love. Our voices be the sound of victory, when we, stand proud

and sing, Our Time Has Come!

Solomon and Sunshine Chambers -- ????

These are the inspirational words of my great-grandfather, and my grandfather. But here it is in the year of our Lord 2008, and my father has yet to add his generation's verse to the family's Bible. He is a sixty-eight-year-old man and his opportunity to pass the Bible to me with his verse inscribed, is rapidly decreasing.

My father does not believe in the prophecy as my grandfather, and great-grandfather. He believes in today, and making the most of it. He wants his legacy to be remembered for what he has done as a scholar and professional, and not as a martyr, or activist. He does not believe in the struggle for the advancement of Black people. He believes that every man should make his own way through the means of education; regardless of the circumstances. He believes that success is colorblind. All that he sees is determination and hard work. Any circumstance can be overcome by determination and hard work. I adamantly disagree with my father. I believe that success, first of all, is a relative word. I think that one can dream of success, but when one arrives at the reality, he has lost so much of himself that the passion for success has turned into a mere achievement.

My father has a lifetime of achievements: certificates, honorary degrees, memorials, foundations. If you can think of any outstanding award that is bestowed upon a human being, my father has one somewhere with his name on it. He is one of the most famous attorneys in the United States. His name alone is said to have settled cases without ever going into litigation. And yes, this man, is my father. A man of strong character, and resiliency, of course he has suffered as all men have suffered. But through his sufferings, he emerged a stronger and more determined man than he was before his crisis.

A "trailblazer" in the field of law for African-Americans who follow in his footsteps; a title he publicly denounces. He is called a paramount of an attorney not just for African-Americans, but for all Americans. When asked of his contributions to law, he humbly refers to Thurgood Marshall and says, "Without his contributions, there would be no place for my own." This man is my father.

At this hour, my father is doing what he has done his entire life; searching for the perfect solution to his current problem. This time the issue he faces is greater than any other he has faced in his life. For the issue is not about losing or winning a case. It is not about the prestige of his name, or his crafty courtroom tactics. It is not about awards, certificates, or foundations. It is about an issue he has eluded, and escaped for sixty-eight years. It is time for my father to relinquish his past, and embrace the present. The time has come for my father to face his ultimate nemesis: himself.

• • •

WASHINGTON, D.C., 2008

"As I stand here before you, Lord, my mind reflects upon the past sixty-eight years of my life. And I wonder why destiny has led me to this place, and this time. I am an old man, Lord. If You had given me this task twenty years ago, I would have been more than able to fulfill it. But tonight, what good am I to you?

"I have spent the last year working, and trying to do Your will but I am tired, Lord. I don't know if my old feebly body can hold on until tomorrow.

"But I do know one thing, Jesus. When I leave this courtroom tomorrow, one way or the other, I won't have to worry about ever coming back into another one again in my life. I'm going to have to rest these old bones.

"Well, Lord, I'm almost through praying. My knees hurt so bad I can hardly stand up. Wait a minute, Lord. I've changed my mind. I'm not quite through yet. I wonder how my father would feel if he knew that his only son had grown up to be in this dubious position. My guess would be very afraid. Afraid that I may die in the same manner in which he died. Could You tell him I'm sorry, Lord? Aw, don't worry about it. As old as I feel, I may be able to tell him personally in a day or two.

"Lord, my mother always said that you won't put any more on us than we can handle. How much more do You think I have left, Lord? Give me my strength for one more day, Lord; just like you did Sampson. Please, Lord, just one more day." Solomon continued to stay on his knees as he held the back of the pew in front of him for support. He said, "Amen," to conclude his prayer, and looked up to see an old man entering the rear of the courtroom.

"I'm sorry, sir, this courtroom is not open to the public. You are not

supposed to be in here. This is a top security building. How did you get in here, anyway?" Solomon asked.

"That's the one good thang 'bout bein' a broke-down old man. Nobody ever pay you no 'tention. 'Course they don't pay you no 'tention when you need it, too. I walked up to that do' and walked straight through it, and ain't nobody said one word to me. When you old like this, son, you 'come invisible." The old man laughed.

"I know the feeling of being old," Solomon said.

"Why, you just a baby, Solomon." The old man laughed again.

"You know my name?" Solomon asked.

"Who don't know Solomon Chambers, the modern-day Moses," the old man whispered. "We need you, son. We need you bad."

"What can one man do against the powers that be?" Solomon asked.

"You ain't just one man. You God's man, and like the good book say, if God be fo' you, who can be against you? If God is in you, son, then you the powuh that be. Who can stand against you?" the old man said with his chest stuck out and shoulders pulled back.

"The United States government!" Solomon sighed.

The old man laid his cane to his side, and slid onto one of the benches.

"Let me tell you somethin', son. Sixty-eight years ago I was convicted of robbin' somebody. I was only sixteen years old. They stuck me in a prison with old overgrown men. I was only a boy. Sixteen years old! And they stuck me in that hole and let me rot for sixty-eight long years. I don't have no family. I don't have no friends. I don't have no nothin'!

"They only let me out so I can die, and they won't have to foot the bill. My whole life is gone. Just wasted! You know I done asked God a million times to just let me die. But He wouldn't. As a matter of fact, I ain't never been sick a day in my life until they let me out of jail. And even now, my body ailin' me, but I ain't been down sick. Who say God ain't got no sense of humor, huhn?" The old man laughed.

"Well, thank Jesus you're a free man now," Solomon said.