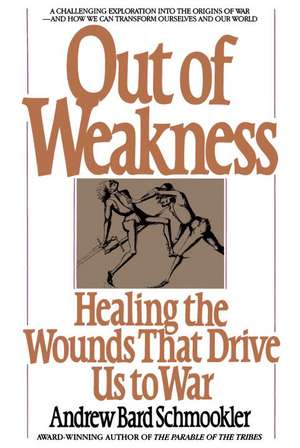

Out of Weakness: Healing the Wounds That Drive Us to War

Autor Andrew Bard Schmookleren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 1988

“A remarkably thorough analysis of the proposition that is our beliefs, conscious and unconscious, which have made war inevitable–and that a change in those assumptions (including the unconscious ones) can free us from the scourge…This is a very hopeful book about a subject that leads many to despair…I believe it will be a most useful contribution to the dialogue about our national security dilemma.”—Willis Harman, President, Institute of Noetic Sciences, author of An Incomplete Guide to the Future

Preț: 120.87 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 181

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.13€ • 25.20$ • 19.49£

23.13€ • 25.20$ • 19.49£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 02-16 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553344776

ISBN-10: 0553344773

Pagini: 384

Dimensiuni: 151 x 230 x 24 mm

Greutate: 0.54 kg

Editura: Bantam Books

ISBN-10: 0553344773

Pagini: 384

Dimensiuni: 151 x 230 x 24 mm

Greutate: 0.54 kg

Editura: Bantam Books

Notă biografică

Andrew Bard Schmookler is Senior Policy Advisor to Search for a Common Ground, Washington, D.C., and a Research Associate of the Center for Psychological Studies in the Nuclear Age, Harvard University.

Extras

Prologue: Out of Weakness

1. THE WARRIOR SPIRIT, War and the Search for Security

War is both the parent and child of fears. For the people of the world today, the expansion of our powers of destruction has increased the scope of our fears. As before, each nation worries about impingement or conquest by rival powers. But a new element has been added. We are haunted by the possibility that in a fit of bellicose passion we human beings may self-destruct. This danger casts a shadow over everything we love.

To avoid this new and cataclysmic danger, we must master an ancient problem. To end the plague of war, we must understand both the adaptive and the maladaptive dimensions of our fears and our efforts to protect ourselves.

For human beings to live in fear is nothing new. Insecurity has been the common lot of civilized peoples: as far back as the written record reaches, societies have preyed upon one another. This has been part of the cost of civilization. Among civilized societies, the struggle for power has continued from the dawn of civilization without relent.

The ceaseless struggle for power has structured the living energies of civilization into the form of fear. Two images of civilization illustrate the structure that fear has imposed: the image of the warrior, whose vital energies of flesh and blood are encased in armor; and that of the fortress city, whose social life is surrounded by thick defensive walls. Fear drives what is alive into a hard, dead shell; it mandates that love is turned inward, while distrust and enmity guard the approaches from the world outside.

This structure governed by fear is adaptive in a world plagued with insecurities. To survive, human societies have made themselves ready to fight, amassing armed forces and adopting a martial spirit in defense of fatherland and national honor. It is the great warriors who have traditionally been sung as heroes, for they have been the most visible molders of peoples' collective destinies. In a world shaped by chronic and inevitable armed conflict, it has been adaptive for civilized peoples to have their values shaped by the demands of war.

The search for security goes on in our times. Where earlier peoples sought stronger metals for their swords, we strive for more accurate missiles. The fortress walls of ancient cities are replaced now by dreams of "Star Wars" bubbles to make us impervious to enemy attack. The technology is new, but the fear and the adaptive strategy are quite ancient.

The nuclear arms race, however, reveals that adaptation is not the whole story. Adaptation means finding the way toward survival. An uncontrolled race for superiority in weapons of mass destruction is clearly not the best strategy for assuring survival for anyone. The inability of the warriors of two mighty nations to seize upon their overriding common interest suggests that dark passions have clouded their reason. Each side may legitimately fear the danger posed by the other. But the greater readiness of each superpower, for the past forty years, to attend to the fear of its dangerous enemy than to reduce the catastrophic danger created by their enmity suggests that maladaptive forces are also at work. A few decades ago, who would have thought that nations armed with such apocalyptic powers could continue their desperate, headlong dash to arm still further? In the 1950s, a comparative handful of nuclear weapons, ready for cumbersome delivery, held the world in terror; now there are tens of thousands of warheads poised minutes from their targets. Yet, both superpowers strive for more weapons with an anxiety and a determination that show no sign of abating.* Something is amiss in our ostensibly self-protective efforts.

There is a saying that when the clock strikes 13 we must question not only the 13th ring but all those that have gone before. For us, the present spectacle of barely restrained escalation in nuclear arms can serve as the 13th ring in the chronicles of the civilized warrior.

Doubtless, part of our present problem is that the nuclear arms race is an atavistic attachment to a strategy that is no longer adaptive. After thousands of years when killing one's enemies enhanced one's security, it is difficult to grasp the implications of the possibility of nuclear winter. In this new kind of war, the blow may ultimately strike him who delivered it as hard as him on whom it falls.

But the problem goes much deeper than the intellectual inertia of strategists always fighting the last war. The persistence of the combative mode in the face of the possibility of mutual annihilation also reveals with striking clarity an irrationally destructive strain that has been present throughout the saga of human strife. There is an attachment to the struggle for preeminence, the need for an evil enemy, a "lust to annihilate." Our means of self-protection have long also been a source of our own endangerment.

The clock has struck 13. It is time to reexamine the warrior spirit that has been shaped and manifested by ten thousand years of civilization.

*As this work goes to press, some most welcome signs of such abatement may be last becoming visible.

1. THE WARRIOR SPIRIT, War and the Search for Security

War is both the parent and child of fears. For the people of the world today, the expansion of our powers of destruction has increased the scope of our fears. As before, each nation worries about impingement or conquest by rival powers. But a new element has been added. We are haunted by the possibility that in a fit of bellicose passion we human beings may self-destruct. This danger casts a shadow over everything we love.

To avoid this new and cataclysmic danger, we must master an ancient problem. To end the plague of war, we must understand both the adaptive and the maladaptive dimensions of our fears and our efforts to protect ourselves.

For human beings to live in fear is nothing new. Insecurity has been the common lot of civilized peoples: as far back as the written record reaches, societies have preyed upon one another. This has been part of the cost of civilization. Among civilized societies, the struggle for power has continued from the dawn of civilization without relent.

The ceaseless struggle for power has structured the living energies of civilization into the form of fear. Two images of civilization illustrate the structure that fear has imposed: the image of the warrior, whose vital energies of flesh and blood are encased in armor; and that of the fortress city, whose social life is surrounded by thick defensive walls. Fear drives what is alive into a hard, dead shell; it mandates that love is turned inward, while distrust and enmity guard the approaches from the world outside.

This structure governed by fear is adaptive in a world plagued with insecurities. To survive, human societies have made themselves ready to fight, amassing armed forces and adopting a martial spirit in defense of fatherland and national honor. It is the great warriors who have traditionally been sung as heroes, for they have been the most visible molders of peoples' collective destinies. In a world shaped by chronic and inevitable armed conflict, it has been adaptive for civilized peoples to have their values shaped by the demands of war.

The search for security goes on in our times. Where earlier peoples sought stronger metals for their swords, we strive for more accurate missiles. The fortress walls of ancient cities are replaced now by dreams of "Star Wars" bubbles to make us impervious to enemy attack. The technology is new, but the fear and the adaptive strategy are quite ancient.

The nuclear arms race, however, reveals that adaptation is not the whole story. Adaptation means finding the way toward survival. An uncontrolled race for superiority in weapons of mass destruction is clearly not the best strategy for assuring survival for anyone. The inability of the warriors of two mighty nations to seize upon their overriding common interest suggests that dark passions have clouded their reason. Each side may legitimately fear the danger posed by the other. But the greater readiness of each superpower, for the past forty years, to attend to the fear of its dangerous enemy than to reduce the catastrophic danger created by their enmity suggests that maladaptive forces are also at work. A few decades ago, who would have thought that nations armed with such apocalyptic powers could continue their desperate, headlong dash to arm still further? In the 1950s, a comparative handful of nuclear weapons, ready for cumbersome delivery, held the world in terror; now there are tens of thousands of warheads poised minutes from their targets. Yet, both superpowers strive for more weapons with an anxiety and a determination that show no sign of abating.* Something is amiss in our ostensibly self-protective efforts.

There is a saying that when the clock strikes 13 we must question not only the 13th ring but all those that have gone before. For us, the present spectacle of barely restrained escalation in nuclear arms can serve as the 13th ring in the chronicles of the civilized warrior.

Doubtless, part of our present problem is that the nuclear arms race is an atavistic attachment to a strategy that is no longer adaptive. After thousands of years when killing one's enemies enhanced one's security, it is difficult to grasp the implications of the possibility of nuclear winter. In this new kind of war, the blow may ultimately strike him who delivered it as hard as him on whom it falls.

But the problem goes much deeper than the intellectual inertia of strategists always fighting the last war. The persistence of the combative mode in the face of the possibility of mutual annihilation also reveals with striking clarity an irrationally destructive strain that has been present throughout the saga of human strife. There is an attachment to the struggle for preeminence, the need for an evil enemy, a "lust to annihilate." Our means of self-protection have long also been a source of our own endangerment.

The clock has struck 13. It is time to reexamine the warrior spirit that has been shaped and manifested by ten thousand years of civilization.

*As this work goes to press, some most welcome signs of such abatement may be last becoming visible.

Descriere

A sweeping social critique in the tradition of Christopher Lasch's The Culture of Narcissism that explores the irrational and unconscious forces that drive people to make war.