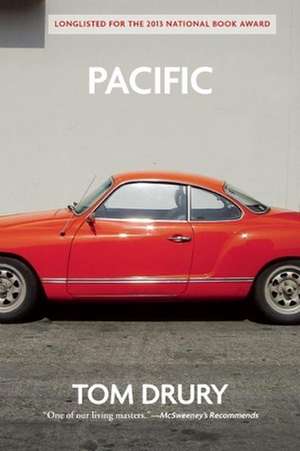

Pacific

Autor Tom Druryen Limba Engleză Paperback – 12 mai 2014

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

National Book Awards (2013)

“Reading Pacific makes me once again fall in love with Drury’s words, and his perception of a world that is full of dangers and passions and mysteries and graces.”—Yiyun Li

In Pacific, Tom Drury revisits the community of Grouse County, the setting of his landmark debut, The End of Vandalism. When fourteen-year-old Micah Darling travels to Los Angeles to reunite with the mother who abandoned him seven years ago, he finds himself out of his league in a land of magical freedom. Back in the Midwest, an ethereal young woman comes to Stone City on a mission that will unsettle the lives of everyone she meets—including Micah’s half-sister, Lyris, and his father, Tiny, a petty thief. An investigation into the stranger’s identity uncovers a darkly disturbed life, as parallel narratives of the comic and tragic, the mysterious and quotidian, unfold in both the country and the city.

In Pacific, Tom Drury revisits the community of Grouse County, the setting of his landmark debut, The End of Vandalism. When fourteen-year-old Micah Darling travels to Los Angeles to reunite with the mother who abandoned him seven years ago, he finds himself out of his league in a land of magical freedom. Back in the Midwest, an ethereal young woman comes to Stone City on a mission that will unsettle the lives of everyone she meets—including Micah’s half-sister, Lyris, and his father, Tiny, a petty thief. An investigation into the stranger’s identity uncovers a darkly disturbed life, as parallel narratives of the comic and tragic, the mysterious and quotidian, unfold in both the country and the city.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 56.88 lei 3-5 săpt. | +7.16 lei 6-12 zile |

| Old Street Publishing Ltd – 2 aug 2016 | 56.88 lei 3-5 săpt. | +7.16 lei 6-12 zile |

| Old Street Publishing Ltd – 10 noi 2015 | 75.90 lei 3-5 săpt. | +9.55 lei 6-12 zile |

Preț: 54.31 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 81

Preț estimativ în valută:

10.39€ • 11.11$ • 8.66£

10.39€ • 11.11$ • 8.66£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780802121172

ISBN-10: 0802121179

Pagini: 194

Dimensiuni: 137 x 206 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Grove Atlantic

ISBN-10: 0802121179

Pagini: 194

Dimensiuni: 137 x 206 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Grove Atlantic

Notă biografică

Tom Drury is also the author of The End of Vandalism, Hunts in Dreams, The Driftless Area, and The Black Brook. His fiction has appeared in The New Yorker, Harper’s Magazine, and The Mississippi Review, and he has been named one of Granta’s “Best Young American Novelists.”

Extras

CHAPTER ONE

Tiny and his son Micah sat on the back porch watching the sun set behind the trees.

“Say you’re carrying something,” said Tiny.

“Like what?”

Micah was fourteen and wore a forest-green stocking hat, his hair like feathers around his calm brown eyes.

“Something of value,” said Tiny. “This ashtray here. Say this ashtray is of value.”

The astray was made of green glass with yellowed seashells glued to the rim. So old it actually might have been of value.

Micah picked it up and walked to the end of the porch and back.

“Good,” said Tiny. “Something of value you carry in front of you and never at your side.”

“I’ll remember.”

“Now say you get in a fight.”

“I won’t.”

“What you do is you put your head down and ram them in the solar plexus. It’s unexpected.”

“I wouldn’t expect it.”

“Well, no one does,” said Tiny. “Sometimes they faint. They always fall over. Oh, and never get a credit card.”

It was a cool night in May. The level light cast a red glow on the grass and trees, the house and the shed.

“Do you still want to go?” said Tiny. “You can call it off any time.”

“I’ve never been in an airplane.”

“We could get Paul Francis to take you up.”

“That’s not what I’m talking about,” said Micah.

Tiny nodded. “I just said that to be saying something.”

A red-tailed hawk came from the north and landed on a hardwood branch with new leaves.

“There’s your hawk,” said Tiny. “Come to say goodbye.”

•

Dan Norman walked out of his house carrying the pieces of a broken table. He and Louise still lived on the old Klar farm on the hill.

The table had fallen apart in the living room. It was not bearing unusual weight and neither Dan nor Louise was nearby when it fell. Just the table’s time, apparently.

A car pulled slowly into the driveway and a woman got out and stood in the yellow circle of the yard light. She had long blond hair, wore a pleated red dress and white gloves.

“You don’t remember me,” she said.

“I do,” said Dan. “Joan Gower.”

He shifted the table pieces over to his left arm and they shook hands.

“Did you know we get second chances, Sheriff?” said Joan.

“Yeah. I’d say I knew that.”

“He will turn again and have compassion upon us and subdue our iniquities.”

“I’m not sheriff anymore, though.”

The door of the house opened and Louise came out wearing a long white button-down shirt as a dress.

“Who are you talking to?”

“Joan Gower.”

“Really.”

Louise had tangled red hair, wild and alive with the light of the house behind her.

“Is this business?”

“I’m getting my son back,” said Joan.

“Give me those, love,” said Louise.

She took the table parts from Dan and headed for the hedge behind the house.

•

Louise put the wood in the trash burner and went on to the barn, the dust of the old farmyard cool and powdery on her feet.

Empty and dark as a church, the barn was no longer used for anything. Louise climbed the ladder and walked across the floor of the hayloft.

The planks had been worn smooth by decades of boots and bales and the changing of seasons. She sat in the open door, dangled her bare legs over the side, lit a cigarette, and smoked in the night.

Dan and Joan were down there, talking in the yard. Louise listened to the muted sound of their voices.

She saw Joan reach up and put her hand on Dan’s shoulder, and then his face. The gesture made Louise happy for some reason.

Maybe that it was beautiful. A graceful sight to be seen in the country, whatever else you might think of it.

•

Lyris and Albert slouched on a davenport smoking grass from a wooden pipe from El Salvador and reading the promotional copy printed on Lyris’s moving boxes.

Lyris was Joan’s other child——Micah’s half sister. At twenty-three she had just moved in with her boyfriend, Albert Robeshaw.

The boxes were said to be good for four moves or twelve years’ storage, and anyone who got more use out of them was directed to sign onto the company’s website and explain.

“As if anyone would do that,” said Albert.

"To whom it may concern," said Lyris.

"We move constantly."

"It’s a hard life. We love your boxes."

“So what are we doing?" said Albert.

“About what?”

“Are we going to see Micah?”

Lyris drew on the pipe. “The little scamper,” she said.

Joan had given her up for adoption at birth. She appeared at Joan and Tiny’s door when she was sixteen and Micah seven. When Joan went away Lyris raised Micah as much as anyone did.

•

Louise came down from the hayloft and walked back to the house. Dan made her a drink and opened a beer, and they faced each other across the kitchen table.

“What have we learned?”

Dan raised his eyebrows. “Sounds like Micah Darling’s going to live with her in California.”

“What’s that got to do with us?”

“I don’t know. Guess she just wanted to tell someone.”

“I saw her touch you,” said Louise.

“Did you?”

Louise picked up the bottle cap from the beer and flicked it at Dan.

“Yeah, man. Pretty sweet scene.”

Dan caught the cap and tossed it toward the corner where it landed on the floor by the wastebasket.

“Where were you?” said Dan.

“Up in the barn.”

“How was it?”

“The same. Good.”

•

Tiny was drinking vodka and Hi-C and watching the Ironman Triathlon on television when Lyris and Albert arrived. An athlete had completed the running part and staggered like a new colt.

“They ought to put him in a wheelbarrow or something,” said Tiny.

Lyris and Albert stood on either side of his chair, looking at the screen.

“Is there archery in this?” Albert asked.

Tiny laughed. “Hell no, there isn’t archery. You swim, ride a bike, and run. It all has to be done in seventeen minutes.”

“That can’t be right,” said Lyris.

“I’m sorry. Hours,” said Tiny.

“Where’s Micah?”

Tiny tipped his head back to gaze at the ceiling. “In his room. Packing his belongings.”

“How are you?”

“I’m all right.”

Albert sat down in a chair to watch TV, or watch Tiny watching TV. Lyris climbed the narrow stairs between pineboard walls lined with pictures that she had cut from magazines and framed.

Micah had Lyris’s old suitcase open on his bed and was folding clothes into it. The suitcase was made of woven sand-colored fibers with red metal edges. From the pocket of her jeans Lyris took out a folded sheet of paper and tucked it in the suitcase.

“Okay, boy, that’s my number,” she said. “You get into trouble, you need to talk, I’m here.”

“Who will call me boy in California?”

“No one. That’s why you shouldn’t leave.”

“Do you think so?”

She shrugged. “Go and see what it is.”

“Are airplanes loud?”

“You get used to it,” said Lyris. “Sometimes they kind of shake.”

“They shake?”

“Well, no. Rattle. Occasionally. From bumps in the clouds. But that’s nothing. If you get nervous just look at the flight people. No matter what happens, they always seem to be thinking, ‘Hmm-hmm-hmm, wonder what I’ll have for supper tonight.”

•

The hotel that Joan stayed in had a tavern with blue neon lights in the windows. She went in and sat at the bar and ordered a Dark and Stormy.

The bartender was a young woman in a black and white smock with horizontal ivy vines above the belt and black-eyed susans below.

“Are you here for the wedding?” she asked.

Joan explained about Micah——how she’d left him seven years ago and wanted a chance to make up for it.

“Oh my,” said the bartender. “That will be quite a change for everyone.”

“It will,” said Joan. “They all probably think it will be a big disaster.”

“Well, it seems brave to me.”

Joan took a drink. “It does?”

“Oh, yeah. Even kind of, what would you say, inspirational.”

“You are the sweetest girl,” said Joan.

“You look like someone on TV.”

“That’s ‘cause I am.”

“Sister Mia. On Forensic Mystic.”

Joan nodded.

“Oh my gosh,” said the bartender. “Would you autograph my hand?”

“I would be honored.”

“Say Sister Mia.”

Joan held the bartender’s hand palm up and using a purple felt pen wrote Sister Mia and drew a heart with an arrow through it.

“People will think I did this myself,” said the bartender.

“Why would you?”

Joan finished her drink and went to her room. It was on the second floor in the back, overlooking a pond with dark trees and houses all around. She turned off the lights in the room and stood on the balcony looking at the water.

•

Tiny made breakfast and Micah came downstairs to the smell of scrambled eggs and canadian bacon and coffee. They ate and Micah asked Tiny if he was going to fight with Joan and Tiny shook his head.

“I don’t think about her that much anymore.”

“You watch her show.”

“Sometimes.”

“You must think of her then.”

Tiny put pepper on his food from a red tin. “I have trouble enough following the plot.”

“I believe that.”

“You have to mind her,” said Tiny. “Maybe you think she owes you. It won’t work if you think like that. You have to mind her like you mind me.”

“I don’t mind you.”

“Use your imagination.”

“You seem more like a brother than a father to me,” said Micah. “And I don’t mean that bad.”

Tiny got up and carried his plate and silverware to the sink, where he washed and rinsed them and put them on the drainboard.

“I don’t take it bad,” he said.

•

Joan arrived in the middle of the morning, and Micah watched her from the window. She crossed the yard smiling, as if thinking it was not so different from what she remembered.

The three of them met on the front porch. For a moment they seemed to be waiting for someone to appear who could tell them what to do.

Then Joan cried, took Micah in her arms, and pressed her head to his chest. He was a head taller than she was.

“I can hear your heart,” she said.

“Come on inside,” said Tiny.

“You have to invite me.”

“I just did.”

“Come in, Mom,” said Micah.

Joan took a chair at the table. Her eyelids and lips were brushed with fine reddish powder, and her skin glowed like a lamp in the room.

“We had eggs and canadian bacon,” said Tiny. “Do you want some?”

“No thank you, I ate at the hotel,” she said quietly.

“How was it?”

“Fair.”

“Where you staying.”

“The Landmark Suites,” said Joan.

“Nice.”

“Oh! There’s the broom.”

“What?” said Tiny.

“I see the broom. I bought it, and now I’m looking right at it.”

“Yeah, we haven’t changed. It’s missing a few straws.”

Micah went upstairs to have a last look at his room. He thought he should feel sad, but he only wondered when he would see it again.

•

“And how is the plumbing business going?” said Joan.

Tiny explained how he lost the plumbing business. The pipes had burst in a house, and the house froze and fell in on itself. The insurance company came in and sued all the contractors.

“Was it your fault?”

“Any pipe you let freeze with water in it, that pipe’ll split. Who puts it in is immaterial. Could be Jesus, pipe’s going to break. Since then I’ve been moving things for people.”

“Do you need money?”

With his hands on the table, Tiny pushed his chair back and looked at her. “I have nothing against you. You want to do things for Micah, and I hope you can. But do I want money? Come on, Joan.”

“I’m sorry.”

“This is my house.”

“I know it.”

She apologized again, and he waved a hand as if to say it was done.

“You want to stay over? You can stay in Lyris’s old room.”

“We fly out of Stone City this afternoon,” said Joan. “Is she going to be here?”

“Her and Albert Robeshaw came over last night. She’s still kind of mad at you.”

“You can’t blame her,” said Joan.

“I don’t.”

•

Tiny’s mother arrived. Her ahadow loomed in the doorway and she yelled hello though Tiny and Joan were sitting right there.

She wore a large Hawaiian shirt, jeans with hammer loops, and Red Wing boots. People feared her, as if she had special powers, but she was just an old lady given to yelling at people and playing with their minds.

Joan stood and gave her a hug, which made her uncomfortable. It wasn’t that she didn’t like Joan, she just wasn’t used to being hugged.

Micah walked down the stairs sideways, dragging Lyris’s suitcase by the red plastic handle. The suitcase bumped down the stairs. The kitchen became crowded, and Tiny took the suitcase and led everyone out to the front yard. They gathered around Micah in the shadow of the willow tree.

“I’m going to miss you,” said Micah’s grandmother. “But you’ll be all right. There’ll be somebody there to help you when you run into trouble.

”

“I will,” said Joan.

“Besides you. There’s someone else.”

Tiny stood behind his mother, gazing absently into the panoramic view of her Hawaiian shirt. Her predictions never surprised him. She made lots of them.

The shirt was dark blue and green and depicted nightfall in an island village of palm trees and grass huts with yellow lights burning in the windows. A pretty place.

Then Micah put thumb and finger to the corners of his mouth and whistled. Pretty soon an old doe goat crept around the side of the house. Micah and Lyris had raised her——fed and tended her, anyhow——there wasn’t a lot of training involved.

The goat came soft-footed down the grass. The reds and whites of her coat had faded to shades of silver. She surveyed the visitors and then stared at Micah, as if to say, “Oh, wait a minute. You’re leaving? That’s what this is all about?”

Micah fell to his knees and roughed up the goat’s long and matted coat. You could see him trying not to cry. His lips trembled, his eyes blurred with tears. The goat stared with slotted eyes at the road that went by the house.

“This is harder than I thought it would be,” said Micah.

•

Tiny and his mother stood in the yard, watching Joan’s car go around the bend. A bank of blue and gray clouds moved in hiding the sun. Colette took out a pipe and a pouch of tobacco and proceeded to smoke.

“And then there was one,” she said. “You think he’s doing the right thing?”

“He might be.”

She walked off to her truck, and Tiny went into the house, closed the door, and walked up the stairs with his shoulders bumping the walls. Micah’s bed was made with a blanket of red and black plaid and a light blue pillow centered beneath the headboard. A hockey stick leaned in the corner, blade wrapped in frayed electrical tape, by an old poster from a movie about heroic dogs.

The bedsprings wheezed like an accordion as Tiny sat down at the foot of the bed. A car went by, the road became quiet, and light rain began to fall against the window.

He sat with his forearms on his knees and his hands folded, remembering when the goat was young, how she and Micah would dance around the yard. Then he got up, pulled the blanket tight at the corners, and left the room.

Tiny and his son Micah sat on the back porch watching the sun set behind the trees.

“Say you’re carrying something,” said Tiny.

“Like what?”

Micah was fourteen and wore a forest-green stocking hat, his hair like feathers around his calm brown eyes.

“Something of value,” said Tiny. “This ashtray here. Say this ashtray is of value.”

The astray was made of green glass with yellowed seashells glued to the rim. So old it actually might have been of value.

Micah picked it up and walked to the end of the porch and back.

“Good,” said Tiny. “Something of value you carry in front of you and never at your side.”

“I’ll remember.”

“Now say you get in a fight.”

“I won’t.”

“What you do is you put your head down and ram them in the solar plexus. It’s unexpected.”

“I wouldn’t expect it.”

“Well, no one does,” said Tiny. “Sometimes they faint. They always fall over. Oh, and never get a credit card.”

It was a cool night in May. The level light cast a red glow on the grass and trees, the house and the shed.

“Do you still want to go?” said Tiny. “You can call it off any time.”

“I’ve never been in an airplane.”

“We could get Paul Francis to take you up.”

“That’s not what I’m talking about,” said Micah.

Tiny nodded. “I just said that to be saying something.”

A red-tailed hawk came from the north and landed on a hardwood branch with new leaves.

“There’s your hawk,” said Tiny. “Come to say goodbye.”

•

Dan Norman walked out of his house carrying the pieces of a broken table. He and Louise still lived on the old Klar farm on the hill.

The table had fallen apart in the living room. It was not bearing unusual weight and neither Dan nor Louise was nearby when it fell. Just the table’s time, apparently.

A car pulled slowly into the driveway and a woman got out and stood in the yellow circle of the yard light. She had long blond hair, wore a pleated red dress and white gloves.

“You don’t remember me,” she said.

“I do,” said Dan. “Joan Gower.”

He shifted the table pieces over to his left arm and they shook hands.

“Did you know we get second chances, Sheriff?” said Joan.

“Yeah. I’d say I knew that.”

“He will turn again and have compassion upon us and subdue our iniquities.”

“I’m not sheriff anymore, though.”

The door of the house opened and Louise came out wearing a long white button-down shirt as a dress.

“Who are you talking to?”

“Joan Gower.”

“Really.”

Louise had tangled red hair, wild and alive with the light of the house behind her.

“Is this business?”

“I’m getting my son back,” said Joan.

“Give me those, love,” said Louise.

She took the table parts from Dan and headed for the hedge behind the house.

•

Louise put the wood in the trash burner and went on to the barn, the dust of the old farmyard cool and powdery on her feet.

Empty and dark as a church, the barn was no longer used for anything. Louise climbed the ladder and walked across the floor of the hayloft.

The planks had been worn smooth by decades of boots and bales and the changing of seasons. She sat in the open door, dangled her bare legs over the side, lit a cigarette, and smoked in the night.

Dan and Joan were down there, talking in the yard. Louise listened to the muted sound of their voices.

She saw Joan reach up and put her hand on Dan’s shoulder, and then his face. The gesture made Louise happy for some reason.

Maybe that it was beautiful. A graceful sight to be seen in the country, whatever else you might think of it.

•

Lyris and Albert slouched on a davenport smoking grass from a wooden pipe from El Salvador and reading the promotional copy printed on Lyris’s moving boxes.

Lyris was Joan’s other child——Micah’s half sister. At twenty-three she had just moved in with her boyfriend, Albert Robeshaw.

The boxes were said to be good for four moves or twelve years’ storage, and anyone who got more use out of them was directed to sign onto the company’s website and explain.

“As if anyone would do that,” said Albert.

"To whom it may concern," said Lyris.

"We move constantly."

"It’s a hard life. We love your boxes."

“So what are we doing?" said Albert.

“About what?”

“Are we going to see Micah?”

Lyris drew on the pipe. “The little scamper,” she said.

Joan had given her up for adoption at birth. She appeared at Joan and Tiny’s door when she was sixteen and Micah seven. When Joan went away Lyris raised Micah as much as anyone did.

•

Louise came down from the hayloft and walked back to the house. Dan made her a drink and opened a beer, and they faced each other across the kitchen table.

“What have we learned?”

Dan raised his eyebrows. “Sounds like Micah Darling’s going to live with her in California.”

“What’s that got to do with us?”

“I don’t know. Guess she just wanted to tell someone.”

“I saw her touch you,” said Louise.

“Did you?”

Louise picked up the bottle cap from the beer and flicked it at Dan.

“Yeah, man. Pretty sweet scene.”

Dan caught the cap and tossed it toward the corner where it landed on the floor by the wastebasket.

“Where were you?” said Dan.

“Up in the barn.”

“How was it?”

“The same. Good.”

•

Tiny was drinking vodka and Hi-C and watching the Ironman Triathlon on television when Lyris and Albert arrived. An athlete had completed the running part and staggered like a new colt.

“They ought to put him in a wheelbarrow or something,” said Tiny.

Lyris and Albert stood on either side of his chair, looking at the screen.

“Is there archery in this?” Albert asked.

Tiny laughed. “Hell no, there isn’t archery. You swim, ride a bike, and run. It all has to be done in seventeen minutes.”

“That can’t be right,” said Lyris.

“I’m sorry. Hours,” said Tiny.

“Where’s Micah?”

Tiny tipped his head back to gaze at the ceiling. “In his room. Packing his belongings.”

“How are you?”

“I’m all right.”

Albert sat down in a chair to watch TV, or watch Tiny watching TV. Lyris climbed the narrow stairs between pineboard walls lined with pictures that she had cut from magazines and framed.

Micah had Lyris’s old suitcase open on his bed and was folding clothes into it. The suitcase was made of woven sand-colored fibers with red metal edges. From the pocket of her jeans Lyris took out a folded sheet of paper and tucked it in the suitcase.

“Okay, boy, that’s my number,” she said. “You get into trouble, you need to talk, I’m here.”

“Who will call me boy in California?”

“No one. That’s why you shouldn’t leave.”

“Do you think so?”

She shrugged. “Go and see what it is.”

“Are airplanes loud?”

“You get used to it,” said Lyris. “Sometimes they kind of shake.”

“They shake?”

“Well, no. Rattle. Occasionally. From bumps in the clouds. But that’s nothing. If you get nervous just look at the flight people. No matter what happens, they always seem to be thinking, ‘Hmm-hmm-hmm, wonder what I’ll have for supper tonight.”

•

The hotel that Joan stayed in had a tavern with blue neon lights in the windows. She went in and sat at the bar and ordered a Dark and Stormy.

The bartender was a young woman in a black and white smock with horizontal ivy vines above the belt and black-eyed susans below.

“Are you here for the wedding?” she asked.

Joan explained about Micah——how she’d left him seven years ago and wanted a chance to make up for it.

“Oh my,” said the bartender. “That will be quite a change for everyone.”

“It will,” said Joan. “They all probably think it will be a big disaster.”

“Well, it seems brave to me.”

Joan took a drink. “It does?”

“Oh, yeah. Even kind of, what would you say, inspirational.”

“You are the sweetest girl,” said Joan.

“You look like someone on TV.”

“That’s ‘cause I am.”

“Sister Mia. On Forensic Mystic.”

Joan nodded.

“Oh my gosh,” said the bartender. “Would you autograph my hand?”

“I would be honored.”

“Say Sister Mia.”

Joan held the bartender’s hand palm up and using a purple felt pen wrote Sister Mia and drew a heart with an arrow through it.

“People will think I did this myself,” said the bartender.

“Why would you?”

Joan finished her drink and went to her room. It was on the second floor in the back, overlooking a pond with dark trees and houses all around. She turned off the lights in the room and stood on the balcony looking at the water.

•

Tiny made breakfast and Micah came downstairs to the smell of scrambled eggs and canadian bacon and coffee. They ate and Micah asked Tiny if he was going to fight with Joan and Tiny shook his head.

“I don’t think about her that much anymore.”

“You watch her show.”

“Sometimes.”

“You must think of her then.”

Tiny put pepper on his food from a red tin. “I have trouble enough following the plot.”

“I believe that.”

“You have to mind her,” said Tiny. “Maybe you think she owes you. It won’t work if you think like that. You have to mind her like you mind me.”

“I don’t mind you.”

“Use your imagination.”

“You seem more like a brother than a father to me,” said Micah. “And I don’t mean that bad.”

Tiny got up and carried his plate and silverware to the sink, where he washed and rinsed them and put them on the drainboard.

“I don’t take it bad,” he said.

•

Joan arrived in the middle of the morning, and Micah watched her from the window. She crossed the yard smiling, as if thinking it was not so different from what she remembered.

The three of them met on the front porch. For a moment they seemed to be waiting for someone to appear who could tell them what to do.

Then Joan cried, took Micah in her arms, and pressed her head to his chest. He was a head taller than she was.

“I can hear your heart,” she said.

“Come on inside,” said Tiny.

“You have to invite me.”

“I just did.”

“Come in, Mom,” said Micah.

Joan took a chair at the table. Her eyelids and lips were brushed with fine reddish powder, and her skin glowed like a lamp in the room.

“We had eggs and canadian bacon,” said Tiny. “Do you want some?”

“No thank you, I ate at the hotel,” she said quietly.

“How was it?”

“Fair.”

“Where you staying.”

“The Landmark Suites,” said Joan.

“Nice.”

“Oh! There’s the broom.”

“What?” said Tiny.

“I see the broom. I bought it, and now I’m looking right at it.”

“Yeah, we haven’t changed. It’s missing a few straws.”

Micah went upstairs to have a last look at his room. He thought he should feel sad, but he only wondered when he would see it again.

•

“And how is the plumbing business going?” said Joan.

Tiny explained how he lost the plumbing business. The pipes had burst in a house, and the house froze and fell in on itself. The insurance company came in and sued all the contractors.

“Was it your fault?”

“Any pipe you let freeze with water in it, that pipe’ll split. Who puts it in is immaterial. Could be Jesus, pipe’s going to break. Since then I’ve been moving things for people.”

“Do you need money?”

With his hands on the table, Tiny pushed his chair back and looked at her. “I have nothing against you. You want to do things for Micah, and I hope you can. But do I want money? Come on, Joan.”

“I’m sorry.”

“This is my house.”

“I know it.”

She apologized again, and he waved a hand as if to say it was done.

“You want to stay over? You can stay in Lyris’s old room.”

“We fly out of Stone City this afternoon,” said Joan. “Is she going to be here?”

“Her and Albert Robeshaw came over last night. She’s still kind of mad at you.”

“You can’t blame her,” said Joan.

“I don’t.”

•

Tiny’s mother arrived. Her ahadow loomed in the doorway and she yelled hello though Tiny and Joan were sitting right there.

She wore a large Hawaiian shirt, jeans with hammer loops, and Red Wing boots. People feared her, as if she had special powers, but she was just an old lady given to yelling at people and playing with their minds.

Joan stood and gave her a hug, which made her uncomfortable. It wasn’t that she didn’t like Joan, she just wasn’t used to being hugged.

Micah walked down the stairs sideways, dragging Lyris’s suitcase by the red plastic handle. The suitcase bumped down the stairs. The kitchen became crowded, and Tiny took the suitcase and led everyone out to the front yard. They gathered around Micah in the shadow of the willow tree.

“I’m going to miss you,” said Micah’s grandmother. “But you’ll be all right. There’ll be somebody there to help you when you run into trouble.

”

“I will,” said Joan.

“Besides you. There’s someone else.”

Tiny stood behind his mother, gazing absently into the panoramic view of her Hawaiian shirt. Her predictions never surprised him. She made lots of them.

The shirt was dark blue and green and depicted nightfall in an island village of palm trees and grass huts with yellow lights burning in the windows. A pretty place.

Then Micah put thumb and finger to the corners of his mouth and whistled. Pretty soon an old doe goat crept around the side of the house. Micah and Lyris had raised her——fed and tended her, anyhow——there wasn’t a lot of training involved.

The goat came soft-footed down the grass. The reds and whites of her coat had faded to shades of silver. She surveyed the visitors and then stared at Micah, as if to say, “Oh, wait a minute. You’re leaving? That’s what this is all about?”

Micah fell to his knees and roughed up the goat’s long and matted coat. You could see him trying not to cry. His lips trembled, his eyes blurred with tears. The goat stared with slotted eyes at the road that went by the house.

“This is harder than I thought it would be,” said Micah.

•

Tiny and his mother stood in the yard, watching Joan’s car go around the bend. A bank of blue and gray clouds moved in hiding the sun. Colette took out a pipe and a pouch of tobacco and proceeded to smoke.

“And then there was one,” she said. “You think he’s doing the right thing?”

“He might be.”

She walked off to her truck, and Tiny went into the house, closed the door, and walked up the stairs with his shoulders bumping the walls. Micah’s bed was made with a blanket of red and black plaid and a light blue pillow centered beneath the headboard. A hockey stick leaned in the corner, blade wrapped in frayed electrical tape, by an old poster from a movie about heroic dogs.

The bedsprings wheezed like an accordion as Tiny sat down at the foot of the bed. A car went by, the road became quiet, and light rain began to fall against the window.

He sat with his forearms on his knees and his hands folded, remembering when the goat was young, how she and Micah would dance around the yard. Then he got up, pulled the blanket tight at the corners, and left the room.

Premii

- National Book Awards Nominee, 2013