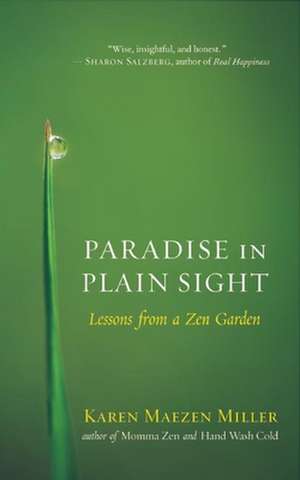

Paradise in Plain Sight: Lessons from a Zen Garden

Autor Karen Maezen Milleren Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 apr 2014

Come See the Garden That Is Your Life

When Zen teacher Karen Maezen Miller and her family land in a house with a hundred-year-old Japanese garden, she uses the paradise in her backyard to glean the living wisdom of our natural world. Through her eyes, rocks convey faith, ponds preach stillness, flowers give love, and leaves express the effortless ease of letting go. The book welcomes readers into the garden for Zen lessons in fearlessness, forgiveness, presence, acceptance, and contentment. Miller gathers inspiration from the ground beneath her feet to remind us that paradise is always here and now.

When Zen teacher Karen Maezen Miller and her family land in a house with a hundred-year-old Japanese garden, she uses the paradise in her backyard to glean the living wisdom of our natural world. Through her eyes, rocks convey faith, ponds preach stillness, flowers give love, and leaves express the effortless ease of letting go. The book welcomes readers into the garden for Zen lessons in fearlessness, forgiveness, presence, acceptance, and contentment. Miller gathers inspiration from the ground beneath her feet to remind us that paradise is always here and now.

Preț: 84.93 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 127

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.26€ • 17.66$ • 13.66£

16.26€ • 17.66$ • 13.66£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781608682522

ISBN-10: 1608682528

Pagini: 192

Dimensiuni: 124 x 201 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: NEW WORLD LIBRARY

ISBN-10: 1608682528

Pagini: 192

Dimensiuni: 124 x 201 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: NEW WORLD LIBRARY

Cuprins

Prologue: Paradise

Part One: Coming Here

Have faith in yourself as the Way.

1. Curb: The View from a Distance

2. Gate: What’s Holding You Back

3. Path: Straight On

4. Ground: Here It Is

5. Sun: What You See

6. Moon: What You Don’t See

Part Two: Living Now

Cover the ground where you stand.

7. Rocks: The Remains of Faith

8. Ponds: The Right View

9. Roots: The Meaning of Life

10. Bamboo: A Forest of Emptiness

11. Palm: The Eternal Now

12. Pine: A Disappearing Breed

Part Three: Letting Go

Make the effort of no effort.

13. Fruit: Swallowing Whole

14. Flowers: Love Is Letting Go

15. Leaves: The Age of Undoing

16. Weeds: A Flourishing Practice

17. Song: Not What You Know

18. Silence: Not What I Say

Epilogue: Rules for a Mindful Garden

Acknowledgments

Permissions

About the Author

Part One: Coming Here

Have faith in yourself as the Way.

1. Curb: The View from a Distance

2. Gate: What’s Holding You Back

3. Path: Straight On

4. Ground: Here It Is

5. Sun: What You See

6. Moon: What You Don’t See

Part Two: Living Now

Cover the ground where you stand.

7. Rocks: The Remains of Faith

8. Ponds: The Right View

9. Roots: The Meaning of Life

10. Bamboo: A Forest of Emptiness

11. Palm: The Eternal Now

12. Pine: A Disappearing Breed

Part Three: Letting Go

Make the effort of no effort.

13. Fruit: Swallowing Whole

14. Flowers: Love Is Letting Go

15. Leaves: The Age of Undoing

16. Weeds: A Flourishing Practice

17. Song: Not What You Know

18. Silence: Not What I Say

Epilogue: Rules for a Mindful Garden

Acknowledgments

Permissions

About the Author

Recenzii

“[Karen Maezen Miller] skillfully weaves vivid details of nature with personal history and such gritty tasks as curbing running bamboo and raking endless sycamore leaves....Miller's graceful writing, hard-learned wisdom, and heartfelt commitment to help her readers find their own bit of paradise here and now make this an inspiring guide.”

— Publishers Weekly

“Wise, insightful, and honest.”

— Sharon Salzberg, author of Real Happiness

“This is one of the most beautiful books I’ve ever read. Karen Maezen Miller has cleared a path for all of us — from pain and confusion to joy and gratitude. She taught me that the secret garden I’ve been searching for has existed all along. I just needed to find the right guide.”

— Priscilla Warner, author of Learning to Breathe and coauthor of the New York Times bestseller The Faith Club

“Paradise in Plain Sight stopped me in my tracks and invited me to look into the backyard of my own life in a different way: with deep attention and radical gratitude. To read this extraordinary book — so brief in length, yet so magnificently deep and so transparently clear — is to remember that home is where I am and that what I need I have.”

— Katrina Kenison, author of Magical Journey

— Publishers Weekly

“Wise, insightful, and honest.”

— Sharon Salzberg, author of Real Happiness

“This is one of the most beautiful books I’ve ever read. Karen Maezen Miller has cleared a path for all of us — from pain and confusion to joy and gratitude. She taught me that the secret garden I’ve been searching for has existed all along. I just needed to find the right guide.”

— Priscilla Warner, author of Learning to Breathe and coauthor of the New York Times bestseller The Faith Club

“Paradise in Plain Sight stopped me in my tracks and invited me to look into the backyard of my own life in a different way: with deep attention and radical gratitude. To read this extraordinary book — so brief in length, yet so magnificently deep and so transparently clear — is to remember that home is where I am and that what I need I have.”

— Katrina Kenison, author of Magical Journey

Notă biografică

Karen Maezen Miller is a Zen Buddhist priest and teacher at the Hazy Moon Zen Center in Los Angeles. The author of Hand Wash Cold and Momma Zen, she leads retreats around the country.

Extras

Chapter 16:

Weeds — A flourishing practice

Empty handed, holding a hoe. — Mahasattva Fu

Paradise is a patch of weeds.

What loyal friends, these undesirables that infiltrate the lawn, insinuate between cracks, and luxuriate in the deep shade of my neglect. Weeds are everywhere, showing up every day. I have quite a bit of help around here but weeds are my most reliable underlings. Where would I be without them? I would run out of reasons to wake up every morning. I would lack motivation and direction. I might consider the job here to be done.

The job here is just beginning.

As if it isn’t obvious enough, I must confess that in these sixteen years of gardening I have not yet learned how to garden. Oops! By this I mean that I do not know the chemistry of soils or the biology of compost. I have not learned the nomenclature; I do not know the right time or way to prune. My most useful tools are the ones farthest from my hands: sun and water. I have not planted a single thing still standing. In all this time in the yard I have cultivated no worthwhile skills, save one that is decidedly unskilled.

I weed.

I offer this up as a modest qualification because I have noticed how reluctantly most people bring themselves to the task. Weeding is not a popular pastime, even among gardeners. Weeds are the very emblem of aversion. Weeding doesn’t produce a rewarding outcome. No grand finale, no big reveal. There’s absolutely nothing to show for it. One spring I directed our revered Mr. Isobe to a troublesome spot in the backyard where invasives were spreading through the mondo grass. He squinted to see what I was pointing to. Subsequently he did not share my distress, but broke into laughter. “You want me to weed?” Perhaps he couldn’t believe that someone of his stature would be asked to stoop to the occasion. Or perhaps I was just imagining what he meant. In any event, I was offended, and I didn’t ask him again. The weeds were all mine.

While I was casting about for something to do for the rest of my life, as we like to characterize temporary forms of employment, I hit upon a scheme. I’d seen how common it was for an otherwise respectable yard to be surrendered over to wilderness for the lack of a spade. And the worse it got, the worse it gets. I suggested to my husband that I start an enterprise — not for landscape design or decoration, for which I was unsuited — but just to weed. I would call it “Just Weeds.” I would go over to people’s houses every week and just pull weeds — probably weeds they didn’t even know they had! I thought it was inspired, but he thought it was lame. So instead I do it every day for no pay. This is how your life becomes rich with purpose. You take care of things that lie right under your feet, and no one even notices.

The most common weeds in the yard are crabgrass, dandelion, and chickweed. The most common weeds in the world are greed, anger, and ignorance.

This is the way to weed. Anchor yourself low to the ground so you can get a good look at what you’re dealing with. Use a spade to loosen the hardpack and go deeper. The next part is tricky. Take hold of the stem and apply your attention, allowing the root to release. Haste and carelessness will only aggravate the situation. Sometimes you can get the root on the first tug. Other times you’ll just tear off the top. Even if you don’t get it all the first time, that’s okay. It may take two or three, ten or twenty, one hundred thousand million times, to get the root completely. Just keep going along like that, encountering the next weed that appears in front of you for the rest of your life.

— —

Ten things to do to spare the garden from stubborn entanglements:

1. Blame no one. I could blame the yardman for the weeds. Or everyone who ever let them fester. The folks who aren’t around for what they haven’t done. The sun, the dirt, the wind, the seed, the rain, and the shade. But what does any of that matter when the spade is in my hands? Blame’s central deceit is that anyone or anything else is responsible for what I think, feel, say and do. Blame is a powerful barrier: like prickly thistle, it spreads pain and disaffection. So why toss fault around? To elevate my ego and justify my self-righteousness, that’s why. Watch that you do not become attached to your version of events. Blame turns the garden into a menace.

2. Take no offense. But I’m so good at it! And usually, offended by what someone doesn’t even know they did. That’s because offense is an inside job. It requires that we ascribe malice and meaning to empty words or actions. Consider the energy we expend to prolong fictional injuries. How hard is it to get over what’s already over? I know: it’s hard. But there’s a way.

3. Forgive. Forgiveness is the cure. Without it, we sell the farm under our feet, subdividing common ground into stingy little parcels that are good for nothing. Forgiveness reconciles the rift between self and other. Like property lines, the barrier between us doesn’t really exist except as a function of greed, anger, or judgment. Forgive someone today — forgive yourself today — and feel the fence lines recede. Suddenly, it’s much easier to move on.

4. Do not compare. There is no greener grass. There is no other side. Your life is not a competition, race or a chase. No one is ahead of you, and there is no way to fall behind. Satisfy yourself with what you have in hand. It may not look like much, but this right here is everything. And, it’s alive.

5. Take off your gloves. A nurseryman once told me, “A real gardener doesn’t wear gloves.” A gardener wears dirt, unafraid to get muddy, scratched, or stung, because hands are how we see, hear, and feel. Native intelligence flows through your fingertips, wisdom received in direct connection with the world, telling you know how deep to dig and how hard to pull, when to gather and when to release. Self-defenses make you timid and clumsy. You can do without the layers of protection.

6. Forget yourself. The world needs a few less people to own their own greatness and few more to own their own humility. So let’s stop pretending. We are never really who we think we are, nor are we anywhere close to the ideal we strive for. My neighbors down the street installed expensive artificial turf on a strip of yard closest to the street. It’s an uncanny likeness. Each blade is a uniform height and color, so it never needs to be watered or cut. It passes as grass from a distance, but up close you can tell it’s not real. Worse yet, weeds still crop up through the weave, and they are even harder to get rid of. When you can face reality without camouflage, yours is the face of compassion. What a sight for sore eyes! No longer obsessed with your self-image, you become genuine. Barefaced and open, your smile is easy; your eyes, wide and bright. Nothing is beneath or beyond you. You can do the smallest things. You carry peace wherever you go and share it with everyone, mindful that we’re all doing our best, and headed in the same direction.

7. Grow old. It isn’t easy, it’s effortless.

8. Have no answers. If, as the ancients say, we are born and die six billion times a day; if, according to modern science, fifty million cells in your body will replace themselves in the time you read this sentence, do you really have an answer for anything? In Zen, we don’t find the answers; we lose the questions. It’s impossible to comprehend the marvel of what we are, or to understand the mystery of life’s impeccable genius. Thankfully, there is no need. You don’t have to know how your heart beats so you can get your mitral valve to open. You don’t have to ace Anatomy 101 to move your arms and feet. The state of not-knowing does not imply a lack of learning, it is the totality of truth. You’re already real, genuine, and functioning perfectly as you are. Weed out the confusion that comes from trying to understand. Don’t think, and you will be grateful.

9. Seek nothing. “All who seek suffer,” Buddhism teaches. “If there is no seeking, only then is there bliss.” That gives you a pretty clear picture of where the suffering begins and ends. Just for one moment take my word that you lack nothing. That you’re perfectly okay even when you’re not okay. If you’ve recognized something in these pages you want to underline and remember, it’s because you already know it. Have faith in yourself as the Way.

10. Go back to 1. The Buddha is still refining his practice.

— —

The old teachers called them “sweet grasses,” the overgrowth that beckons from the side of the road. Dense and shimmery, they are eye candy to the weary pilgrim, but poisonous. Wander close and they’ll make you sick. Let me chew on this for awhile — anger, blame, guilt — let me hide out in those brambles — fear and worry — let me lie down and go to sleep — rumination and make-believe — so I don’t have to keep going. The path leads on. There’s no end in sight. You can only see what’s right in front of you. The scenery may not seem interesting or the time, productive. You get bored and look around for, well, something.

Shouldn’t I be making progress? Going faster? Accomplishing more? Getting somewhere? Surely there’s more to this trip than one measly breath at a time, one lousy foot in front of the other? I don’t see what’s so special about it.

We can lose our lives in these sidetracks: dwelling on the past and anticipating the future; judging, resisting and debating with ourselves; falling again for the familiar ruts. To be fair, poison ivy isn’t all bad: its berries feed foraging birds and wildlife. But by all means you don’t want to tromp around in it. In tiny doses, hemlock is medicinal. But don’t make a meal of it.

When folks begin to practice, they can be set back by how hard it is. They might have expected to be good at it — for certain they expected something — but what they are good at is something else altogether.

Why is it so hard to just breathe? Because you’ve been practicing holding your breath.

Why is it so hard to keep my eyes open? Because you’ve been practicing falling asleep.

Why is it so hard to be still? Because you’ve been practicing running amok.

Why is it so hard to be quiet? Because you’ve been practicing talking to yourself.

Why is it so hard to pay attention? Because you’ve been practicing inattention.

Why is it so hard to relax? Because you’ve been practicing stress.

Why is it so hard to trust? Because you’ve been practicing fear.

Why is it so hard to have faith? Because you’ve been trying to know.

Why is it so hard to feel good? Because you’ve been practicing feeling bad.

Whatever you practice, you’ll get very good at, and you’ve been practicing these things forever. Take your own life as proof that practice works as long as you keep doing it. Just replace a harmful practice with one that does no harm.

The desperate traveler keeps going, and a change takes place. The landscape transforms from a jungle pocked with toxins into an open field. The interruptions are fewer; the diversions, farther between. The sweet grasses are left behind. The field is one we cultivate step by step: swinging breath like a hoe to clear the surface of mind, using samadhi like a spade to go deeper. What does it take to turn a pit of poison into paradise? We can say we know, but we still have to do it over and over again, and never quit.

After practicing shikantaza, just sitting, for forty years, Maezumi Roshi said,

“I think I’m beginning to do it.”

Every time I step into the garden, I’ve landed my dream job. Only it’s not called “Just Weeds.” It’s just weeds, the business of a buddha. I think I’m beginning to do it.

Weeds — A flourishing practice

Empty handed, holding a hoe. — Mahasattva Fu

Paradise is a patch of weeds.

What loyal friends, these undesirables that infiltrate the lawn, insinuate between cracks, and luxuriate in the deep shade of my neglect. Weeds are everywhere, showing up every day. I have quite a bit of help around here but weeds are my most reliable underlings. Where would I be without them? I would run out of reasons to wake up every morning. I would lack motivation and direction. I might consider the job here to be done.

The job here is just beginning.

As if it isn’t obvious enough, I must confess that in these sixteen years of gardening I have not yet learned how to garden. Oops! By this I mean that I do not know the chemistry of soils or the biology of compost. I have not learned the nomenclature; I do not know the right time or way to prune. My most useful tools are the ones farthest from my hands: sun and water. I have not planted a single thing still standing. In all this time in the yard I have cultivated no worthwhile skills, save one that is decidedly unskilled.

I weed.

I offer this up as a modest qualification because I have noticed how reluctantly most people bring themselves to the task. Weeding is not a popular pastime, even among gardeners. Weeds are the very emblem of aversion. Weeding doesn’t produce a rewarding outcome. No grand finale, no big reveal. There’s absolutely nothing to show for it. One spring I directed our revered Mr. Isobe to a troublesome spot in the backyard where invasives were spreading through the mondo grass. He squinted to see what I was pointing to. Subsequently he did not share my distress, but broke into laughter. “You want me to weed?” Perhaps he couldn’t believe that someone of his stature would be asked to stoop to the occasion. Or perhaps I was just imagining what he meant. In any event, I was offended, and I didn’t ask him again. The weeds were all mine.

While I was casting about for something to do for the rest of my life, as we like to characterize temporary forms of employment, I hit upon a scheme. I’d seen how common it was for an otherwise respectable yard to be surrendered over to wilderness for the lack of a spade. And the worse it got, the worse it gets. I suggested to my husband that I start an enterprise — not for landscape design or decoration, for which I was unsuited — but just to weed. I would call it “Just Weeds.” I would go over to people’s houses every week and just pull weeds — probably weeds they didn’t even know they had! I thought it was inspired, but he thought it was lame. So instead I do it every day for no pay. This is how your life becomes rich with purpose. You take care of things that lie right under your feet, and no one even notices.

The most common weeds in the yard are crabgrass, dandelion, and chickweed. The most common weeds in the world are greed, anger, and ignorance.

This is the way to weed. Anchor yourself low to the ground so you can get a good look at what you’re dealing with. Use a spade to loosen the hardpack and go deeper. The next part is tricky. Take hold of the stem and apply your attention, allowing the root to release. Haste and carelessness will only aggravate the situation. Sometimes you can get the root on the first tug. Other times you’ll just tear off the top. Even if you don’t get it all the first time, that’s okay. It may take two or three, ten or twenty, one hundred thousand million times, to get the root completely. Just keep going along like that, encountering the next weed that appears in front of you for the rest of your life.

— —

Ten things to do to spare the garden from stubborn entanglements:

1. Blame no one. I could blame the yardman for the weeds. Or everyone who ever let them fester. The folks who aren’t around for what they haven’t done. The sun, the dirt, the wind, the seed, the rain, and the shade. But what does any of that matter when the spade is in my hands? Blame’s central deceit is that anyone or anything else is responsible for what I think, feel, say and do. Blame is a powerful barrier: like prickly thistle, it spreads pain and disaffection. So why toss fault around? To elevate my ego and justify my self-righteousness, that’s why. Watch that you do not become attached to your version of events. Blame turns the garden into a menace.

2. Take no offense. But I’m so good at it! And usually, offended by what someone doesn’t even know they did. That’s because offense is an inside job. It requires that we ascribe malice and meaning to empty words or actions. Consider the energy we expend to prolong fictional injuries. How hard is it to get over what’s already over? I know: it’s hard. But there’s a way.

3. Forgive. Forgiveness is the cure. Without it, we sell the farm under our feet, subdividing common ground into stingy little parcels that are good for nothing. Forgiveness reconciles the rift between self and other. Like property lines, the barrier between us doesn’t really exist except as a function of greed, anger, or judgment. Forgive someone today — forgive yourself today — and feel the fence lines recede. Suddenly, it’s much easier to move on.

4. Do not compare. There is no greener grass. There is no other side. Your life is not a competition, race or a chase. No one is ahead of you, and there is no way to fall behind. Satisfy yourself with what you have in hand. It may not look like much, but this right here is everything. And, it’s alive.

5. Take off your gloves. A nurseryman once told me, “A real gardener doesn’t wear gloves.” A gardener wears dirt, unafraid to get muddy, scratched, or stung, because hands are how we see, hear, and feel. Native intelligence flows through your fingertips, wisdom received in direct connection with the world, telling you know how deep to dig and how hard to pull, when to gather and when to release. Self-defenses make you timid and clumsy. You can do without the layers of protection.

6. Forget yourself. The world needs a few less people to own their own greatness and few more to own their own humility. So let’s stop pretending. We are never really who we think we are, nor are we anywhere close to the ideal we strive for. My neighbors down the street installed expensive artificial turf on a strip of yard closest to the street. It’s an uncanny likeness. Each blade is a uniform height and color, so it never needs to be watered or cut. It passes as grass from a distance, but up close you can tell it’s not real. Worse yet, weeds still crop up through the weave, and they are even harder to get rid of. When you can face reality without camouflage, yours is the face of compassion. What a sight for sore eyes! No longer obsessed with your self-image, you become genuine. Barefaced and open, your smile is easy; your eyes, wide and bright. Nothing is beneath or beyond you. You can do the smallest things. You carry peace wherever you go and share it with everyone, mindful that we’re all doing our best, and headed in the same direction.

7. Grow old. It isn’t easy, it’s effortless.

8. Have no answers. If, as the ancients say, we are born and die six billion times a day; if, according to modern science, fifty million cells in your body will replace themselves in the time you read this sentence, do you really have an answer for anything? In Zen, we don’t find the answers; we lose the questions. It’s impossible to comprehend the marvel of what we are, or to understand the mystery of life’s impeccable genius. Thankfully, there is no need. You don’t have to know how your heart beats so you can get your mitral valve to open. You don’t have to ace Anatomy 101 to move your arms and feet. The state of not-knowing does not imply a lack of learning, it is the totality of truth. You’re already real, genuine, and functioning perfectly as you are. Weed out the confusion that comes from trying to understand. Don’t think, and you will be grateful.

9. Seek nothing. “All who seek suffer,” Buddhism teaches. “If there is no seeking, only then is there bliss.” That gives you a pretty clear picture of where the suffering begins and ends. Just for one moment take my word that you lack nothing. That you’re perfectly okay even when you’re not okay. If you’ve recognized something in these pages you want to underline and remember, it’s because you already know it. Have faith in yourself as the Way.

10. Go back to 1. The Buddha is still refining his practice.

— —

The old teachers called them “sweet grasses,” the overgrowth that beckons from the side of the road. Dense and shimmery, they are eye candy to the weary pilgrim, but poisonous. Wander close and they’ll make you sick. Let me chew on this for awhile — anger, blame, guilt — let me hide out in those brambles — fear and worry — let me lie down and go to sleep — rumination and make-believe — so I don’t have to keep going. The path leads on. There’s no end in sight. You can only see what’s right in front of you. The scenery may not seem interesting or the time, productive. You get bored and look around for, well, something.

Shouldn’t I be making progress? Going faster? Accomplishing more? Getting somewhere? Surely there’s more to this trip than one measly breath at a time, one lousy foot in front of the other? I don’t see what’s so special about it.

We can lose our lives in these sidetracks: dwelling on the past and anticipating the future; judging, resisting and debating with ourselves; falling again for the familiar ruts. To be fair, poison ivy isn’t all bad: its berries feed foraging birds and wildlife. But by all means you don’t want to tromp around in it. In tiny doses, hemlock is medicinal. But don’t make a meal of it.

When folks begin to practice, they can be set back by how hard it is. They might have expected to be good at it — for certain they expected something — but what they are good at is something else altogether.

Why is it so hard to just breathe? Because you’ve been practicing holding your breath.

Why is it so hard to keep my eyes open? Because you’ve been practicing falling asleep.

Why is it so hard to be still? Because you’ve been practicing running amok.

Why is it so hard to be quiet? Because you’ve been practicing talking to yourself.

Why is it so hard to pay attention? Because you’ve been practicing inattention.

Why is it so hard to relax? Because you’ve been practicing stress.

Why is it so hard to trust? Because you’ve been practicing fear.

Why is it so hard to have faith? Because you’ve been trying to know.

Why is it so hard to feel good? Because you’ve been practicing feeling bad.

Whatever you practice, you’ll get very good at, and you’ve been practicing these things forever. Take your own life as proof that practice works as long as you keep doing it. Just replace a harmful practice with one that does no harm.

The desperate traveler keeps going, and a change takes place. The landscape transforms from a jungle pocked with toxins into an open field. The interruptions are fewer; the diversions, farther between. The sweet grasses are left behind. The field is one we cultivate step by step: swinging breath like a hoe to clear the surface of mind, using samadhi like a spade to go deeper. What does it take to turn a pit of poison into paradise? We can say we know, but we still have to do it over and over again, and never quit.

After practicing shikantaza, just sitting, for forty years, Maezumi Roshi said,

“I think I’m beginning to do it.”

Every time I step into the garden, I’ve landed my dream job. Only it’s not called “Just Weeds.” It’s just weeds, the business of a buddha. I think I’m beginning to do it.