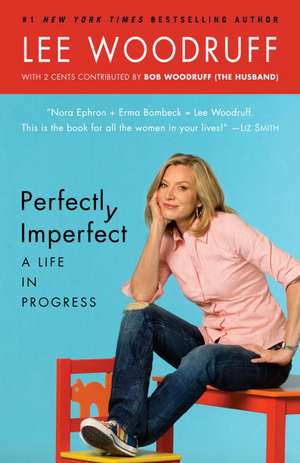

Perfectly Imperfect: A Life in Progress

Autor Lee Woodruff Bob Woodruffen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2010

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Books for a Better Life (2009)

Preț: 82.20 lei

Preț vechi: 99.86 lei

-18% Nou

Puncte Express: 123

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.73€ • 16.82$ • 13.11£

15.73€ • 16.82$ • 13.11£

Disponibilitate incertă

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812979022

ISBN-10: 0812979028

Pagini: 235

Ilustrații: CHAPTER-OPENING PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 141 x 201 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0812979028

Pagini: 235

Ilustrații: CHAPTER-OPENING PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 141 x 201 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

Lee Woodruff is the life and family contributor for ABC’s Good Morning America and a freelance writer. She is on the board of trustees of the Bob Woodruff Family Foundation, a nonprofit organization that provides critical resources and support to our nation’s injured service members, veterans, and their families, especially those affected by the signature hidden injuries of war: traumatic brain injury and combat stress. Lee Woodruff lives in Westchester County, New York, with her husband, ABC News anchor Bob Woodruff, and their four children.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter One

Amusement Park Mecca

Do you want a margarita?” yelled the insipidly chirpy waitress in the Hawaiian shirt. We were in the Jimmy Buffett–themed restaurant at Universal Studios, Orlando, and she was trying to be heard over “Come Monday,” which was blaring from the speaker system.

“No,” I said wearily. My feet throbbed, and, as the designated pack mule, I’d been lugging the twenty-pound backpack with the camera, extra batteries and chargers, water, fleeces, and enough snacks to outfit an Everest expedition. I’d been so distracted getting everyone else breakfast that morning that I hadn’t had more than a few bites of the kids’ cold toast. My blood sugar level was alarmingly low. I was ready to drink the ketchup right out of the crusty red bottle on the table.

“Really...?” The waitress sounded genuinely surprised, almost disdainful. “You sure you don’t want a margarita?”

What I said was “No thank you.” What I really wanted to do was to grab her by the front of her fluorescent shirt with one fist, like they did in spaghetti westerns, and snarl, “Listen, amiga, you see these four kids here? You think I can possibly deal with this theme park and all four of them if I start downing tequila? Do you want me to blow chunks on the Hulk? Would you like me to pass out here in Margaritaville and lose this brood somewhere between Seuss Landing and Fear Factor Live?”

Instead, I kept my voice even, my countenance beaming, and an adoring look focused on my kids. I didn’t want them to suspect for a moment that I wasn’t as ecstatic as they were to be there. I’d shouldered the responsibility of continually making sure everyone was in tow, of keeping all four kids contented despite age gaps greater than the drop at Splash Mountain, determined that they view me as “Most Fun Mom.” I wanted them to remember that I’d cheerily gone on all the rides with them, from Jimmy Neutron’s Nicktoon Blast to the Amazing Adventures of Spider-Man. I wanted it seared in their brains that I’d let them order chocolate sundaes from room service and stay up late with in-room movies. I was focused on creating a fond memory so that, on my deathbed, they could all recall the time I’d loosened the purse strings and let them buy souvenirs and eat unlimited amounts of greasy park food. This was downright radical compared to our normal household rules.

I knew enough to understand that it would be years before the day-to- day martyrdom of mothering would even hit their radar screens. The nutritious home-cooked dinners, the homework patrol, and the midnight snuggles when they had the flu that made up the real heroics of parenting didn’t earn medals. Those acts wouldn’t truly be appreciated until my kids had children of their own and were bleeding out of their ears from the decibel level on an elementary school field-trip bus ride.

What they would remember, what would live in the collective film library of their childhood memories, was the highlight reel: the trips to Magic Kingdom, the ski weekends, and the beach vacations. The rest of it, the work in the trenches, would be like background noise; it was low-level radar, like the commercials in between the Oscar presentations. I needed to make this one big.

•••

Our country’s theme parks are the proving ground for parental excellence. I’ve yet to meet a mom or dad who has been able to escape a pilgrimage to Disney, Universal, Six Flags, or any of the other überintense, megapacked square miles of finger-lickin’ Fun for the Whole Family. Folks will clip coupons, hunt for bargains, look for deals, and save for years—anything to cross that threshold for the kids and snap those cherished family photos with Mickey or Buzz Lightyear with a giant roller coaster in the background.

But the pages in our family album wouldn’t have the whole picture. My husband would have to be Photoshopped into the frame because, once again, right before the trip he had been sent on assignment to cover some world event; what had been planned as a family vacation had ended up as a milestone in single parenting. The responsibility, plus the twenty-pound backpack, was now on my Sherpa shoulders.

So here I was, alone with four kids: Mack, age sixteen, Cathryn, nearly fourteen, and twins Nora and Claire, who were seven. This was my big weekend in Orlando, where I was determined to prove that I was, in fact, the best mom in the world.

I felt the promise this one day had to erase all the recent failures: the moments when I had been distracted, or hadn’t read to the twins at bedtime, or had spent too much time on my e-mail. There was always so much more I could be doing, should be doing if I was to be a GREAT mom.

So far we had braved threatening thunderclouds, pouring rain, and then blistering humidity. No wonder the park had been quiet and the lines not too long; we’d been soaked through to our footwear, and the weight on my back had felt ten pounds heavier. I had become an extra in Saving Private Ryan. As the afternoon had worn on, though, the sun had emerged, and masses of people began pushing through the turnstiles in all of their exuberant glory, as if Oprah herself had announced her giant giveaway sweepstakes. It seemed that everyone had a shot at the shiny red Chevrolet if they poured through the gates right now.

We’d snagged the last available table in the Jimmy Buffett restaurant and were soon digging into a coma-inducing amount of food: obese hamburgers, fries like fence posts nachos dripping with cheese and jalapeños, sheer excess. This was vacation food, designed to stop arterial blood in its tracks. The “Volcano” song began blasting over the speakers, and some sort of earsplitting alarm with lights went off in the restaurant as a giant papier-mâché volcano began to smoke and froth. Soon green margarita water was running down the mountain and into a huge swirling goblet poised over the bar, reminiscent of Linda Blair in The Exorcist. My kids were transfixed. I was catatonic.

On the giant TV screens of the all-Buffett, all-the-time Sirius radio simulcast, men in silly shark-shaped foam hats holding up beers and women in what looked like a perimenopausal wet T-shirt contest with unspeakable sayings scrawled on their chests danced across the screen, wagging everything that was waggable. It looked like a colossal episode of Grandparents Gone Wild.

“Mom, what’s wrong with those ladies?” Claire asked. Mack just smiled with an “I’ve seen it all before” teenage look. Lord knows what movies and Internet sites he had feasted on, out from under my watchful gaze.

“Those ladies are drunk,” I said, using my weary church lady voice. “And that makes them do really stupid things.” I was eager to change the subject.

My two younger children were getting a far earlier education in the marginal areas of life than the older ones had. Was I just worn down or simply inured? Or was it harder to rear two younger ones on good guy/bad guy morality tales when there were older siblings in the house? The teenagers understood that there could be gray areas and room for little white lies. My parental explanation skills had to span Barney to blow jobs, the colors of the rainbow to, ahem, rainbow parties. (Note to reader: if you need an explanation here, ask your teens. On second thought, don’t ask your teens.) Come to think of it, a theme park was one of the few places where I could pretty much guarantee that everybody would be happy. Most of the time. If only I could keep track of them.

My defenses weaken in an amusement park. My normally high threshold for saying no lowers just enough for my kids to climb over the fence, and this, unfortunately, applies to more than greasy food. Perhaps that is just what the owners count on. Fatigue, exhaustion, the beating sun, or rain—it’s almost easier to hand over the wallet than to fight the good fight. Oh, what the heck, I think to myself as Cathryn works on me for a hammered leather bracelet I know she will never wear again. “We’re on vacation,” I say with false cheer. This seems to mean that all of my rules are out the window. I’m now rolling with it.

With each turn through the fantastically constructed “lands” of the park there were endless opportunities for food and merchandising. I remained strong as we passed numerous booths for great globs of fried dough the size of a large pizza. Big and small people passed me gnawing on giant caveman-sized turkey legs like packs of wolves, ripping the pink meat with their teeth as they shambled forward like extras in Night of the Living Dead.

Spider-Man mugs, key chains with our names on them, flip-flops with SpongeBob’s head; in my cheeseburger-and-roller-coaster-induced trance I told myself we would probably never be here again, so it was okay to buy some mementos. I found myself peeling off more bills, even though I knew with certainty that these items would end up in the garage-sale basket or church thrift shop by spring cleaning. These tchotchkes would be cherished for exactly one day and then become prime candidates for my famous biannual “crap control” efforts as I swept through the house with industrial-sized black garbage bags.

“Can I have this necklace?” my daughter Nora asked sweetly. It was some kind of sea-themed monstrosity from the Jaws ride, distantly related to the ubiquitous pukka shells popular in my teens, when an “authentic” strand of pukka was the height of chic. Where had they found all these pukkas? What the heck was a pukka?

Meanwhile, I was fascinated by my son’s approach to the park, something he had looked forward to for a long time. He walked a few paces behind us, continually texting up-to-the-minute info about each ride to his friends back home on his cell phone. He was becoming a kind of real-time information booth on which rides were cool, which ones were “duds,” and what we simply had to do while we were here.

It took all I had not to be a mom as I watched this. I fought the urge to say, “Put away the electronics, kiddo, and just enjoy this...be in the moment.” Because, in fact, he was in the moment. This was how our kids did moments now; they multitasked and instant- messaged through some of the great moments in life, one eye on the keyboard and one on real time. I had to remind myself that just because it was different from how I’d processed experiences as a kid, it didn’t make it wrong. I held my tongue and took a bite of Cathryn’s red licorice to settle the cheeseburger.

As we walked through the park’s uncanny versions of lower Manhattan, Wall Street, and San Francisco’s Fishermen’s Wharf, I marveled at how sophisticated amusement parks had become. Why bother to actually visit all these places separately when you could just come here? You’d save a fortune on airfare and hotels.

Growing up in upstate New York, my sisters and I had thought that the height of excitement was a visit to Storytown in Lake George Village. I remember the real-life Cinderella in the pumpkin carriage and her magical dress with cut-glass beads. There was the Frontier Town train ride chugging slowly through the badlands. Although I could see the unpainted boards on the back of the two-dimensional saloon, and the bandit mechanically popped up on cue when the little train chugged around the boulder, it was all simply magical.

Before computer generation, before elaborate headset video games, Steven Spielberg, and holographic special effects, our expectations were so reasonable, so minimal that I was simply bamboozled by that long-ago theme park.

Did my kids feel transported today? It would be hard to compare. They had each become such jaded, sophisticated consumers, flooded daily with images and transported by sensational, three-dimensional graphics.

Still, no matter how elaborate and lifelike the graphics and holograms got, it seemed there was no substitute for good old- fashioned Newton-defying physics to get the kids riled up. This was evident from the screams as I found myself in line for the Hulk rollercoaster, a giant green monster of rails and poles that thundered over the top of the walkway, twisting like a worm on dry pavement with scores of terrified riders.

“It’s going to be so cool to go totally upside down,” said Mack. I’m not much of a meat eater, so the giant cheeseburger in paradise was still objecting at every turn of my digestive system. My mother says this is her food “reporting back to her.” I remembered seeing something that week on TV about a ground beef recall, the biggest in history. My first cheeseburger in months and it could be contaminated meat from a theme park. I eyed the screaming riders corkscrewing above me.

As we approached the Hulk, a sign with a yardstick indicating the required height stood prominently by the entrance. My twins fell a good five inches short.

Seeing this, Claire huffed and began to wail. Unlike her more

Zen-like twin sister, she was caught between two worlds. She wanted desperately to be as grown up as her fourteen-year-old sister and sixteen-year-old brother, yet she milked her “youngest” status in the family for every last drop.

“I want to go on the Hulk,” she said, crossing her arms over her chest and thrusting out her lower lip. “Why can’t I go? Why do I have to be that tall?” Sigh.

As the four of us tried to reason with her, she sat down by the entrance and put her head in her hands. I had a lose-lose scenario here: ride with my sixteen-year-old or mollify my crying second grader. Mack had a year left in our home before college, I reflected, and this might be the last roller-coaster ride of our lives together. Nostalgia and reason won out. I chose the ride with Mack, leaving the twins behind with a grim-faced Cathryn, who had no interest in the belly-lurching experience.

Once we were strapped into a chair with so much padding I thought we might be going intergalactic, the Hulk took off slowly, then, on the incline, instantly achieved warp speed. I couldn’t even turn my head to see how Mack, next to me, was doing. All I could do was scream like Tippi Hedren as each turn buffeted me against the halter, speed instantly peeling my lips inside out while the centrifugal force plastered me back against the seat. I had a flashback of my first time in Disney World as a teenager, when the It’s a Small World attraction became stuck and we were trapped inside a room of costumed dolls singing the song repeatedly in twenty languages. That had actually been more terrifying than this roller coaster, I thought grimly.

From the Hardcover edition.

Amusement Park Mecca

Do you want a margarita?” yelled the insipidly chirpy waitress in the Hawaiian shirt. We were in the Jimmy Buffett–themed restaurant at Universal Studios, Orlando, and she was trying to be heard over “Come Monday,” which was blaring from the speaker system.

“No,” I said wearily. My feet throbbed, and, as the designated pack mule, I’d been lugging the twenty-pound backpack with the camera, extra batteries and chargers, water, fleeces, and enough snacks to outfit an Everest expedition. I’d been so distracted getting everyone else breakfast that morning that I hadn’t had more than a few bites of the kids’ cold toast. My blood sugar level was alarmingly low. I was ready to drink the ketchup right out of the crusty red bottle on the table.

“Really...?” The waitress sounded genuinely surprised, almost disdainful. “You sure you don’t want a margarita?”

What I said was “No thank you.” What I really wanted to do was to grab her by the front of her fluorescent shirt with one fist, like they did in spaghetti westerns, and snarl, “Listen, amiga, you see these four kids here? You think I can possibly deal with this theme park and all four of them if I start downing tequila? Do you want me to blow chunks on the Hulk? Would you like me to pass out here in Margaritaville and lose this brood somewhere between Seuss Landing and Fear Factor Live?”

Instead, I kept my voice even, my countenance beaming, and an adoring look focused on my kids. I didn’t want them to suspect for a moment that I wasn’t as ecstatic as they were to be there. I’d shouldered the responsibility of continually making sure everyone was in tow, of keeping all four kids contented despite age gaps greater than the drop at Splash Mountain, determined that they view me as “Most Fun Mom.” I wanted them to remember that I’d cheerily gone on all the rides with them, from Jimmy Neutron’s Nicktoon Blast to the Amazing Adventures of Spider-Man. I wanted it seared in their brains that I’d let them order chocolate sundaes from room service and stay up late with in-room movies. I was focused on creating a fond memory so that, on my deathbed, they could all recall the time I’d loosened the purse strings and let them buy souvenirs and eat unlimited amounts of greasy park food. This was downright radical compared to our normal household rules.

I knew enough to understand that it would be years before the day-to- day martyrdom of mothering would even hit their radar screens. The nutritious home-cooked dinners, the homework patrol, and the midnight snuggles when they had the flu that made up the real heroics of parenting didn’t earn medals. Those acts wouldn’t truly be appreciated until my kids had children of their own and were bleeding out of their ears from the decibel level on an elementary school field-trip bus ride.

What they would remember, what would live in the collective film library of their childhood memories, was the highlight reel: the trips to Magic Kingdom, the ski weekends, and the beach vacations. The rest of it, the work in the trenches, would be like background noise; it was low-level radar, like the commercials in between the Oscar presentations. I needed to make this one big.

•••

Our country’s theme parks are the proving ground for parental excellence. I’ve yet to meet a mom or dad who has been able to escape a pilgrimage to Disney, Universal, Six Flags, or any of the other überintense, megapacked square miles of finger-lickin’ Fun for the Whole Family. Folks will clip coupons, hunt for bargains, look for deals, and save for years—anything to cross that threshold for the kids and snap those cherished family photos with Mickey or Buzz Lightyear with a giant roller coaster in the background.

But the pages in our family album wouldn’t have the whole picture. My husband would have to be Photoshopped into the frame because, once again, right before the trip he had been sent on assignment to cover some world event; what had been planned as a family vacation had ended up as a milestone in single parenting. The responsibility, plus the twenty-pound backpack, was now on my Sherpa shoulders.

So here I was, alone with four kids: Mack, age sixteen, Cathryn, nearly fourteen, and twins Nora and Claire, who were seven. This was my big weekend in Orlando, where I was determined to prove that I was, in fact, the best mom in the world.

I felt the promise this one day had to erase all the recent failures: the moments when I had been distracted, or hadn’t read to the twins at bedtime, or had spent too much time on my e-mail. There was always so much more I could be doing, should be doing if I was to be a GREAT mom.

So far we had braved threatening thunderclouds, pouring rain, and then blistering humidity. No wonder the park had been quiet and the lines not too long; we’d been soaked through to our footwear, and the weight on my back had felt ten pounds heavier. I had become an extra in Saving Private Ryan. As the afternoon had worn on, though, the sun had emerged, and masses of people began pushing through the turnstiles in all of their exuberant glory, as if Oprah herself had announced her giant giveaway sweepstakes. It seemed that everyone had a shot at the shiny red Chevrolet if they poured through the gates right now.

We’d snagged the last available table in the Jimmy Buffett restaurant and were soon digging into a coma-inducing amount of food: obese hamburgers, fries like fence posts nachos dripping with cheese and jalapeños, sheer excess. This was vacation food, designed to stop arterial blood in its tracks. The “Volcano” song began blasting over the speakers, and some sort of earsplitting alarm with lights went off in the restaurant as a giant papier-mâché volcano began to smoke and froth. Soon green margarita water was running down the mountain and into a huge swirling goblet poised over the bar, reminiscent of Linda Blair in The Exorcist. My kids were transfixed. I was catatonic.

On the giant TV screens of the all-Buffett, all-the-time Sirius radio simulcast, men in silly shark-shaped foam hats holding up beers and women in what looked like a perimenopausal wet T-shirt contest with unspeakable sayings scrawled on their chests danced across the screen, wagging everything that was waggable. It looked like a colossal episode of Grandparents Gone Wild.

“Mom, what’s wrong with those ladies?” Claire asked. Mack just smiled with an “I’ve seen it all before” teenage look. Lord knows what movies and Internet sites he had feasted on, out from under my watchful gaze.

“Those ladies are drunk,” I said, using my weary church lady voice. “And that makes them do really stupid things.” I was eager to change the subject.

My two younger children were getting a far earlier education in the marginal areas of life than the older ones had. Was I just worn down or simply inured? Or was it harder to rear two younger ones on good guy/bad guy morality tales when there were older siblings in the house? The teenagers understood that there could be gray areas and room for little white lies. My parental explanation skills had to span Barney to blow jobs, the colors of the rainbow to, ahem, rainbow parties. (Note to reader: if you need an explanation here, ask your teens. On second thought, don’t ask your teens.) Come to think of it, a theme park was one of the few places where I could pretty much guarantee that everybody would be happy. Most of the time. If only I could keep track of them.

My defenses weaken in an amusement park. My normally high threshold for saying no lowers just enough for my kids to climb over the fence, and this, unfortunately, applies to more than greasy food. Perhaps that is just what the owners count on. Fatigue, exhaustion, the beating sun, or rain—it’s almost easier to hand over the wallet than to fight the good fight. Oh, what the heck, I think to myself as Cathryn works on me for a hammered leather bracelet I know she will never wear again. “We’re on vacation,” I say with false cheer. This seems to mean that all of my rules are out the window. I’m now rolling with it.

With each turn through the fantastically constructed “lands” of the park there were endless opportunities for food and merchandising. I remained strong as we passed numerous booths for great globs of fried dough the size of a large pizza. Big and small people passed me gnawing on giant caveman-sized turkey legs like packs of wolves, ripping the pink meat with their teeth as they shambled forward like extras in Night of the Living Dead.

Spider-Man mugs, key chains with our names on them, flip-flops with SpongeBob’s head; in my cheeseburger-and-roller-coaster-induced trance I told myself we would probably never be here again, so it was okay to buy some mementos. I found myself peeling off more bills, even though I knew with certainty that these items would end up in the garage-sale basket or church thrift shop by spring cleaning. These tchotchkes would be cherished for exactly one day and then become prime candidates for my famous biannual “crap control” efforts as I swept through the house with industrial-sized black garbage bags.

“Can I have this necklace?” my daughter Nora asked sweetly. It was some kind of sea-themed monstrosity from the Jaws ride, distantly related to the ubiquitous pukka shells popular in my teens, when an “authentic” strand of pukka was the height of chic. Where had they found all these pukkas? What the heck was a pukka?

Meanwhile, I was fascinated by my son’s approach to the park, something he had looked forward to for a long time. He walked a few paces behind us, continually texting up-to-the-minute info about each ride to his friends back home on his cell phone. He was becoming a kind of real-time information booth on which rides were cool, which ones were “duds,” and what we simply had to do while we were here.

It took all I had not to be a mom as I watched this. I fought the urge to say, “Put away the electronics, kiddo, and just enjoy this...be in the moment.” Because, in fact, he was in the moment. This was how our kids did moments now; they multitasked and instant- messaged through some of the great moments in life, one eye on the keyboard and one on real time. I had to remind myself that just because it was different from how I’d processed experiences as a kid, it didn’t make it wrong. I held my tongue and took a bite of Cathryn’s red licorice to settle the cheeseburger.

As we walked through the park’s uncanny versions of lower Manhattan, Wall Street, and San Francisco’s Fishermen’s Wharf, I marveled at how sophisticated amusement parks had become. Why bother to actually visit all these places separately when you could just come here? You’d save a fortune on airfare and hotels.

Growing up in upstate New York, my sisters and I had thought that the height of excitement was a visit to Storytown in Lake George Village. I remember the real-life Cinderella in the pumpkin carriage and her magical dress with cut-glass beads. There was the Frontier Town train ride chugging slowly through the badlands. Although I could see the unpainted boards on the back of the two-dimensional saloon, and the bandit mechanically popped up on cue when the little train chugged around the boulder, it was all simply magical.

Before computer generation, before elaborate headset video games, Steven Spielberg, and holographic special effects, our expectations were so reasonable, so minimal that I was simply bamboozled by that long-ago theme park.

Did my kids feel transported today? It would be hard to compare. They had each become such jaded, sophisticated consumers, flooded daily with images and transported by sensational, three-dimensional graphics.

Still, no matter how elaborate and lifelike the graphics and holograms got, it seemed there was no substitute for good old- fashioned Newton-defying physics to get the kids riled up. This was evident from the screams as I found myself in line for the Hulk rollercoaster, a giant green monster of rails and poles that thundered over the top of the walkway, twisting like a worm on dry pavement with scores of terrified riders.

“It’s going to be so cool to go totally upside down,” said Mack. I’m not much of a meat eater, so the giant cheeseburger in paradise was still objecting at every turn of my digestive system. My mother says this is her food “reporting back to her.” I remembered seeing something that week on TV about a ground beef recall, the biggest in history. My first cheeseburger in months and it could be contaminated meat from a theme park. I eyed the screaming riders corkscrewing above me.

As we approached the Hulk, a sign with a yardstick indicating the required height stood prominently by the entrance. My twins fell a good five inches short.

Seeing this, Claire huffed and began to wail. Unlike her more

Zen-like twin sister, she was caught between two worlds. She wanted desperately to be as grown up as her fourteen-year-old sister and sixteen-year-old brother, yet she milked her “youngest” status in the family for every last drop.

“I want to go on the Hulk,” she said, crossing her arms over her chest and thrusting out her lower lip. “Why can’t I go? Why do I have to be that tall?” Sigh.

As the four of us tried to reason with her, she sat down by the entrance and put her head in her hands. I had a lose-lose scenario here: ride with my sixteen-year-old or mollify my crying second grader. Mack had a year left in our home before college, I reflected, and this might be the last roller-coaster ride of our lives together. Nostalgia and reason won out. I chose the ride with Mack, leaving the twins behind with a grim-faced Cathryn, who had no interest in the belly-lurching experience.

Once we were strapped into a chair with so much padding I thought we might be going intergalactic, the Hulk took off slowly, then, on the incline, instantly achieved warp speed. I couldn’t even turn my head to see how Mack, next to me, was doing. All I could do was scream like Tippi Hedren as each turn buffeted me against the halter, speed instantly peeling my lips inside out while the centrifugal force plastered me back against the seat. I had a flashback of my first time in Disney World as a teenager, when the It’s a Small World attraction became stuck and we were trapped inside a room of costumed dolls singing the song repeatedly in twenty languages. That had actually been more terrifying than this roller coaster, I thought grimly.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Lee Woodruff is a modern day truth-teller. She is a laugh-out-loud funny, complex, contradictory, compassionate sister in the struggles and sweet successes of contemporary motherhood, sisterhood and wife-dom. An immediately relatable group of recollections and reflections on the often unfair, unexpected and unbelievably beautiful paths of a woman’s life.”—Jamie Lee Curtis

“Nora Ephron + Erma Bombeck = Lee Woodruff. This is the book for all the women in your lives!”—Liz Smith, syndicated columnist

“Reading Lee Woodruff’s warm, joyful, heartfelt essays on everything from sagging knees to facing a child’s disability is a little like staying up all night dishing with your best friend. You’ll nod in agreement, laugh out loud, shed a few tears, and come away with a renewed appreciation for the magic of everyday moments, which Woodruff celebrates with her characteristic humor and grace in Perfectly Imperfect.”—Ann Pleshette Murphy, parenting contributor for ABC’s Good Morning America and author of The 7 Stages of Motherhood

“I want to snuggle up with a cup of tea and Lee Woodruff herself. Perfectly Imperfect is like having an old, dear friend who you haven’t seen in awhile regale you with stories about life that you swear could be your own. This book will become my constant companion.” —Rita Wilson

From the Hardcover edition.

“Nora Ephron + Erma Bombeck = Lee Woodruff. This is the book for all the women in your lives!”—Liz Smith, syndicated columnist

“Reading Lee Woodruff’s warm, joyful, heartfelt essays on everything from sagging knees to facing a child’s disability is a little like staying up all night dishing with your best friend. You’ll nod in agreement, laugh out loud, shed a few tears, and come away with a renewed appreciation for the magic of everyday moments, which Woodruff celebrates with her characteristic humor and grace in Perfectly Imperfect.”—Ann Pleshette Murphy, parenting contributor for ABC’s Good Morning America and author of The 7 Stages of Motherhood

“I want to snuggle up with a cup of tea and Lee Woodruff herself. Perfectly Imperfect is like having an old, dear friend who you haven’t seen in awhile regale you with stories about life that you swear could be your own. This book will become my constant companion.” —Rita Wilson

From the Hardcover edition.

Premii

- Books for a Better Life Finalist, 2009