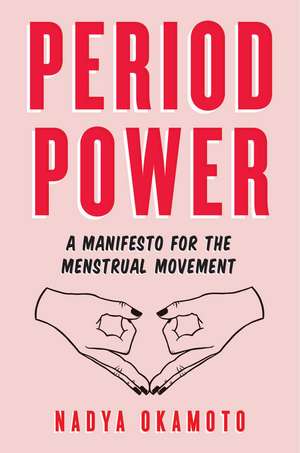

Period Power: A Manifesto for the Menstrual Movement

Autor Nadya Okamoto Ilustrat de Rebecca Elfasten Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2022 – vârsta ani

Throughout history, periods have been hidden from the public. They’re taboo. They’re embarrassing. They’re gross. And due to a crumbling or nonexistent national sex ed program, they are misunderstood. Because of these stigmas, a status quo has been established to exclude people who menstruate from the seat at the decision-making table, creating discriminations like the tampon tax, medicines that favor male biology, and more.

Period Power aims to explain what menstruation is, shed light on the stigmas and resulting biases, and create a strategy to end the silence and prompt conversation about periods.

Preț: 48.20 lei

Preț vechi: 58.50 lei

-18% Nou

Puncte Express: 72

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.23€ • 10.02$ • 7.75£

9.23€ • 10.02$ • 7.75£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-16 aprilie

Livrare express 15-21 martie pentru 33.39 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781534430204

ISBN-10: 1534430202

Pagini: 368

Ilustrații: 3-c cvr (spfx: 3 flat colors + spot uv); 4 b-w line illustrations

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

Colecția Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

ISBN-10: 1534430202

Pagini: 368

Ilustrații: 3-c cvr (spfx: 3 flat colors + spot uv); 4 b-w line illustrations

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

Colecția Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

Notă biografică

Nadya Okamoto grew up in Portland and currently attends Harvard College. She is the founder and executive director of PERIOD (Period.org), an organization she founded at the age of sixteen, which is now the largest youth-run NGO in women’s health, and one of the fastest growing ones here in the United States. She is also the cofounder and spokesperson of Next Fellows (NextFellows.org). In 2017, Nadya ran for office in Cambridge, Massachusetts. While she did not win, her campaign team made historic waves in mobilizing young people on the ground and at polls.

Extras

Period Power

•

Periods are powerful. Human life would literally not exist without them. They are what make reproduction possible and keep our wombs ready to bear children, if or when we choose to do that.

The common experience of menstruation connects people all over the world. Think about it: if you were assigned female at birth, most likely you will get your period on a monthly basis for around forty years of your life. It doesn’t matter where you are from, how you identify, or what access to resources you have. And if you don’t get your period during menstruation age, it means that your body is telling you either that you are pregnant or that your health needs attention. Though, it’s also important to know that when birth control is used without breaks, menstruation may stop as well.

To strengthen the way we advocate for periods, we need to understand what a period is in the first place. In the United States we still live in a culture where there is no expectation that we’ll learn about periods. Even when it is taught (in schools, by parents, by friends), it’s often taught in a way that limits our understanding of what we might call the menstrual experience.

Basic sex education—if available—usually starts in the final years of elementary school and continues into middle school. For those of us who have already experienced it, we might have cringe-worthy memories of our teachers holding up bananas or wooden models of penises to demonstrate how to properly roll a condom on. My favorite memory is of when my eighth-grade science teacher took a red condom, blew it up, and shouted, “See? It works for any size!”

My experience with sex education in elementary and middle school was in gender-segregated classrooms. Teachers often shuffle boys into one classroom and girls into another. In the boys’ classroom the health teacher might explain that the boys’ voices are going to get lower, their testicles will descend, and hairs will grow in unfamiliar places on their bodies.

In the other classroom the girls are learning about their bodies too. They will learn about their own hair growth, about the development of boobs, and about hormones and the new emotions that they might start to feel. This might also be the first time periods are brought up in the classroom. The teacher will hold up a tampon and pad and explain what products are available and the basics of how to use them. But the experience of actually menstruating will not be covered. You won’t find out what the blood will actually look like or what to do if you feel extreme pain while menstruating. The teachers won’t tell you what you should do if you stop menstruating suddenly. The option of using sustainable alternatives such as menstrual cups and reusable pads, rather than a typical tampon or pad, will not be discussed.

From the moment the classroom separates into boys and girls, the girls learn to feel shame about openly talking about menstruation, and this prevents future conversations and questions from surfacing. Girls learn that the topic of periods is something you either keep to yourself or you mention only to other girls, in private circles. And boys often don’t formally learn anything about menstruation. They are taught that it isn’t any of their business, that it’s weird to even be curious.

Menstruator or not, you still have to share spaces with many people who are. Everyone, regardless of sex or gender identity, should know what periods are and should feel comfortable talking about them—this is necessary in order to build inclusive and egalitarian communities. So, let’s dive in.

“Period” and “menstrual cycle” are two terms that are used to indicate the time of the month when the body excretes blood, but the words don’t mean exactly the same thing. The “menstrual cycle” refers to the approximately twenty-eight-day process during which the body prepares for pregnancy. A “period” is just one brief stop in a much larger menstrual cycle.

![]()

The diagram above gives us a look into a menstruator’s pelvic area, right between the hips. The two ovaries hold the eggs, and the whole menstrual cycle is directed by two of our hormone friends: estrogen and progesterone.

At the beginning of each cycle, estrogen and progesterone trigger the creation of the endometrium, which is a lining on the inside walls of the uterus. Made of tissue and blood, the endometrium is spongy enough to make a perfect landing place for a fertilized egg. When pregnancy does occur, the uterus is often referred to as the womb.

Ovulation happens when a menstruator’s ovaries release a matured egg about halfway through a menstrual cycle. As you can see from the diagram, in order to get to the uterus, the matured egg travels through the fallopian tubes. The egg basically just sits in the fallopian tube or the uterus and waits, hoping to be fertilized by a sperm cell. Most of the time pregnancy does not occur, which causes the uterine lining to break off from the uterine wall and exit the body through the vaginal canal. This action is what we call a period.

When I first got my period, I was scared. I knew what menstruation was, but no one had ever told me how period blood would look, smell, and feel. So, here it is—the bloody truth in all its glory:

What period blood actually looks like, how it smells, the color, and how much of it comes out will vary across menstrual experiences. There is no “normal” version of menstruation. All bodies are different, so period experiences will also be different. Yes, the menstrual cycle is approximately a twenty-eight-day interval, but the cycle is rarely precisely twenty-eight days—and some menstruators sometimes will bleed between periods.1

On average a menstruator will lose anywhere from five to twelve teaspoons, or about thirty to seventy-two milliliters, of blood in one menstrual cycle.2 Sixty milliliters of blood or more is considered a heavy flow. But how can someone measure the amount of blood? Each regular-size tampon holds about five milliliters of blood;3 so this means that if you are using more than twelve tampons per period that are getting fully soaked, then you should go see a doctor. Another way to figure out how much blood you are expelling is to use menstrual cups, which often have marks for measurement on their sides.

When period flow gets very heavy, more than eighty milliliters per cycle, it’s called menorrhagia, and losing this much blood can cause one to feel tired and short of breath—both of which are symptoms of anemia. Having such a heavy flow is not only a hassle because more period products are needed, but it can also be extremely painful. The opposite of this condition, a very light period of less than twenty-five milliliters of blood lost, is called hypomenorrhea.4 So what causes some of us to have only light spotting once a month, and others to experience prolonged menstrual cycles that involve changing pads multiple times in an hour?

Menstruators who have had children or are in perimenopause (the phase right before menopause) typically have heavier flows because menorrhagia can be caused by hormone imbalance—high estrogen and low progesterone leads to more bleeding and clots (passing more than one per day)—but menorrhagia can occur for a number of different reasons, such as certain medications that interfere with blood clotting, uterine fibroids (benign tumors), and polyps (benign growths).5,6 What can you do to regulate or help lessen the pain of period flow? Use the right products for you, eat well, and exercise in a healthy way.7

The color of period blood can also be anywhere from dark brown or even black to a very vibrant red color. This difference in color does not necessarily have any implication for one’s health when within the red spectrum. The color of the blood is dependent on how long the blood, tissue, or even clots have been exposed to oxygen. It’s similar to how your blood changes color if you cut your skin. When you first start to bleed, the color is this very bright red. After letting the cut heal a bit (hopefully with a bandage and disinfectant), the scab that forms is very dark, almost purple. The color of blood darkens with more exposure to oxygen because the pigment concentrates as the water in the blood evaporates.8 The brighter the period blood, the less time it has been in your uterus. The blood flow tends to get a bit heavier on day two or three of your period, so this is when the color of one’s period blood might become brighter.9

The consistency of period blood is probably what people are most in the dark about. No one really tells you what your period is going to feel like, much less what the actual blood is going to be like. Most of my guy friends assume that period blood is watery, like when you get a bloody nose. Incorrect. Your menstrual blood might be watery some of the time, particularly in the first few cycles or in the final days of your period, but it won’t only be like that—and it might not be like that at all for some menstruators. Since vaginal mucus also comes out during a period, the discharge is sometimes slippery and feels a bit like jelly. It’s also pretty normal for period blood to look a little clumpy, from small blood clots. There is nothing to worry about if any clots appear on a period product or in the toilet. This just means that your body is pushing out the menstrual blood faster than your body can break down the clots. Clots are a concern only if they are the size of a quarter or larger.10

Do not feel embarrassed about how your period blood smells, and definitely don’t try to fix it by douching. Douching and forcibly cleaning out your uterus can actually be very unhealthy because it changes the uterus’s natural acidity. It is totally normal for your vagina and period blood to have distinct odors. In fact, menstrual blood is supposed to have that smell. Some might describe this smell as a bit metallic. It isn’t just blood you’re smelling; it’s also mucus and tissue from the lining, as well as bacteria and other fluids. And the smell is stronger when these things sit in your uterus for longer.

If your vaginal discharge or period blood starts to have a fishy scent, that’s when you should see a doctor. There are some common infections, such as bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis, that are known to have a fishy scent. Luckily, these infections can be easily cured with antibiotics.11 The truth is, after the first few times, you’ll get familiar with your period, and the smell of your own period blood and vaginal discharge will become completely recognizable. So, if you suddenly start to notice that it smells different, then you know to go to the doctor and ask questions.12

Pooping more during your period? Also totally normal. When progesterone levels suddenly drop immediately after your period starts (after reaching maximum production right before), that sort of release can cause your bowels to open up a bit more.13

Menstruation usually starts when a person is between ten and fifteen years old, with the average age of menarche being twelve years old. There is no “correct” age when someone should get their first period, and there are a lot of biological and environmental factors that affect when menarche begins.14 Usually, in the six months leading up to menarche, a menstruator will notice more vaginal discharge than usual.15 Vaginal discharge is absolutely normal: it’s a sort of housekeeping function where glands in the vagina and cervix produce fluids to help carry dead cells and any bacteria out of the body. The discharge can vary in color and texture but is usually a white or cloudy-colored thick paste.16

There are theories about the age at which menarche occurs and what it can tell you about your future and current life, especially since studies have shown that both hormones and stress can influence when you get your period. Some of these theories say that an early first period can signify an unsettled childhood, and that if menarche occurs at either a very young age or a very late age, that can mean a higher chance of heart disease.17 Another observation is that experiencing menarche at a younger age is linked to breast cancer.18 But ultimately the most important thing is that the first period (when blood actually comes out of the vagina) indicates that a menstruator has the ability to get pregnant.

The menstrual career (a term that we’ll use to refer to the years when menstruation happens) extends until menopause occurs. After menopause happens, a person can no longer get pregnant.19 There is no process to determine when a menstruator can expect to experience menopause, but in the United States the average age is fifty-two.20 The process of menopause can be a strenuous one that may involve vaginal dryness, hot flashes and chills, abrupt mood changes, trouble sleeping, lower energy, and so on. Of course, different people will experience different symptoms, but having irregular periods during perimenopause is very common. A menstruator is considered to be in menopause when a full twelve months have passed without a period.21

It is not only women who menstruate. Some transgender men and people who identify as nonbinary or genderqueer (or others) but who were assigned female at birth might still experience periods. For many readers this may be the first time you’ve thought about the intersectionality of gender and periods before, but it is an extremely important discussion to have early on, to ensure that the Menstrual Movement is inclusive of all period experiences. I will admit that in my early days of menstrual activism, I did not consider that anyone other than women could experience menstruation. However, since learning about it, gender inclusivity when talking about periods has become one of my priorities.

It’s important to use language that is inclusive of all menstrual experiences. For transgender men and genderqueer people (and others) who still experience menstruation and have uteruses, vaginas, ovaries, and fallopian tubes, periods can be very difficult—not only because of menstrual health management, but also because menstruation is a reminder that their sex (assigned at birth) does not match their gender identity. As you may have noticed, I avoid using terms such as “feminine hygiene” and “feminine products” in an effort to be gender-inclusive.

The word “menarche” is made up of two Greek words: “men,” which means “month,” and “arche,” which means “beginning.” So the term literally means “the first occurrence of a monthly event.” It is the beginning of something that starts when you’re young and continues through much of your life.

“Amenorrhea” is the word used to describe when menstruation is absent for someone who is of menstruating age—when they have missed three or more of their periods or haven’t gotten their period before the age of fifteen. Amenorrhea is usually caused by pregnancy, breast-feeding, or menopause. When someone gets pregnant, they do not experience menstruation because the uterine lining is needed to cultivate the fertilized egg.22 Amenorrhea can also be caused by a problem with the reproductive organs or unregulated hormone levels, or disruption of normal hormone levels as a result of birth control.23

Periods are sort of magical in the way that they can tell us when our bodies need a bit more attention. For example, I ran for city council in Cambridge, Massachusetts, when I was nineteen years old. Doing so was one of the most exhausting experiences of my life—from how emotionally draining it was to be under scrutiny at all times, to the physical fatigue of canvassing for at least four hours per day.

I did not get my period for the entire duration of my campaign—literally from the week before I announced my candidacy in March, all the way until the day after Election Day, November 8. My doctors could explain my period’s break only in relation to the stress and perhaps increased and abnormal (for me, at least) activity that canvassing so often requires.

In anticipation of a potential sperm cell that can fertilize the egg, two weeks prior to menstruation, estrogen and progesterone orchestrate premenstrual syndrome, more commonly referred to as PMS. It is not irregular to meet someone who doesn’t fully understand what a period is but is definitely familiar with PMS—especially men who use the term “PMS” to refer to that “time of month” when they perceive women as more emotionally on edge.

Who hasn’t heard jokes about PMS? When I was growing up, boys and girls being moody or overly emotional were called out for being “on their period.” My sisters and I would also tease my mom about menstruating when she had odd cravings or would start randomly crying about things that seemed trivial to us. I heard these jokes on my favorite television shows and in school hallways as boys competed with one another to see who was more “manly.” While all these jokes exacerbate the stigma around periods in a very negative way—by painting periods as something that makes women perhaps less stable and thus less capable—these assumptions are based on very real symptoms of PMS.

PMS symptoms, which affect an estimated 75 percent of menstruators, include “mood swings, tender breasts, food cravings, fatigue, irritability and depression.”24 Other symptoms include social withdrawal, having trouble concentrating, crying spells, heightened anxiety, muscle pain, and so much more. Though the list of potential symptoms is long, most menstruators experience only a few of them and not severely.25 PMS is very normal, and symptoms can be reduced and even stopped with basic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like Advil and Motrin, or basic hormonal therapy like birth control (which can help regulate or healthily stop periods).26

If the PMS symptoms are extreme, even to the point where the menstruator can’t get out of bed, then they could be suffering from a condition such as endometriosis (which we will explore in a bit) or premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). PMDD is a severe form of PMS that induces a lot of pain, like strong menstrual cramps and headaches. Severe PMS like this is difficult to handle every month and can lead to poor mental health—the cramps and negative moods can seriously affect a menstruator’s confidence and perception of their own ability.27

If you have to miss something because you have bad cramps, tell someone that is why! The more we legitimize periods and period pain, we will help people think of it as something that happens to everybody, which it does.

—Elizabeth Yuko, sex educator and writer28

As I said, it’s very common to experience some degree of pain during your period. Most of the time it’s perfectly normal and fine, even if it’s unpleasant. At other times the pain can be an indication that something is wrong, so we do need to pay attention. Here are various kinds and causes of menstrual pain. I hope this information doesn’t scare you but rather empowers you to know your body!

Painful menstruation, also known as dysmenorrhea, is the number one cause of absenteeism in menstruating adolescents and in menstruators younger than thirty years old.29 Up to 80 percent of menstruators struggle with varying levels of menstrual pain in their lifetime.30 At least 10 percent of these menstruators are temporarily physically disabled by extreme symptoms.31

Because menstrual cramps are so common, young menstruators often assume it to be a natural part of having your period—even when the cramps are debilitating. While there are no cures for cramps, there are remedies that can reduce the severity of the symptoms, but in order to find the right treatments, menstruators have to speak out about their period experience. As more young women have come forward with their personal stories of feeling incapacitated by menstrual pain, dysmenorrhea has increasingly been recognized as a serious medical condition. It is important to talk about period pain—not only because it may help lead to more menstruators finding effective remedies, but also because severe menstrual cramps could actually be endometriosis, which is much more serious (and, if left untreated, can cause more permanent damage to internal tissue), rather than simply normal cramps.32

Menstrual cramps are caused by chemicals called prostaglandins, which are produced by the uterine lining that grows during the menstrual cycle. These chemicals cause surrounding muscles to contract, triggering sharp pains in the lower abdomen and lower back areas, similar to labor pains. The cramps usually start a few days before menstruation begins and last for up to four days. Other symptoms of dysmenorrhea include “nausea, vomiting, sweating, dizziness, headaches,” and sometimes diarrhea.33 These cramps usually start when puberty begins and will last for around a decade, so younger menstruators are more at risk for painful periods. Cramps also tend to be worse for those who have never given birth or who naturally have heavy flows.34

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as Advil, Motrin, and generic ibuprofen can be used to block the production of prostaglandins—and these drugs are often more effective for period cramps than other basic painkillers, like Tylenol.35 Some menstruators have their own home remedies for preventing painful periods—whether that be taking warm baths or using heating pads or sipping certain favorite decaffeinated teas. Menstrual cramps can also be lessened with a healthier diet that lowers the intake of fat, alcohol, and caffeine; and by engaging in less stressful and more active lifestyles.36

Cramping pain that is caused by a specific condition is called secondary dysmenorrhea, and an estimated 5 to 10 percent of menstruators suffer from these conditions.37 These include endometriosis, uterine fibroids, and pelvic inflammatory disease.38

Endometriosis is a gynecological disorder and chronic condition that makes menstruation a very painful and difficult process, with heavier flows, extreme fatigue, and chronic pain around the pelvis. Those who suffer from this condition may experience congestive dysmenorrhea, a fancy term for really painful periods, where the pain is a deep, constant severe aching. This intense pain usually begins before and ends after one’s period. While endometriosis can typically occur in menstruators between the ages of fifteen and forty-four, the symptoms are more apparent for women in their thirties and forties.39 Endometriosis may also cause deep dyspareunia, which means that sex is extremely painful—usually triggered by pressure on the cervix. Even going to the bathroom might be painful.40,41 And it is not guaranteed that symptoms of endometriosis will stop after menopause, when menstruation no longer occurs.42

Endometriosis is a condition in which the uterine lining (the endometrium) grows outside the uterus.43 The endometrial tissue will act normally and will thicken, break down, and bleed as it usually does during menstruation. However, when the tissue isn’t in the uterus, there is nowhere for the blood to exit the body, so it gets trapped. This irritates the surrounding body tissue and can cause the tissue to scar and stick together. Too much adhesion of the tissue can even cause the pelvic anatomy to distort (like the colon sticks to the back of the uterus or an ovary).44 In some cases of endometriosis, endometriomas (ovarian cysts made of endometrial tissue) may form.45 These cysts are associated with heightened pain during menstruation.46

Endometriosis is also directly linked to infertility. A study conducted in 2009 found that about 47 percent of infertile menstruators had endometriosis.47 Unfortunately, the condition never disappears once you have it, but the symptoms may be less severe at certain points.48 Most symptoms will subside when menopause occurs, because endometriosis is an “estrogen-dependent disease.”49

Endometriosis is extremely hard to diagnose because many of its symptoms are extreme versions of a usual menstrual experience. On average, someone with endometriosis goes seven years before any formal diagnosis.50 The only way to diagnose endometriosis is with a laparoscopic inspection of the pelvis—an invasive procedure that uses a video camera to examine internal organs.51 Another issue that may prevent a diagnosis is the fact that period pain is so common and there is no “normal” level of pain. Many menstruators underestimate the severity of their condition, and it’s also difficult for doctors to gauge when period pain becomes serious enough to demand the laparoscopic surgery.52 In 2011 a study found that 11 percent of all menstruators who had not already been diagnosed have endometriosis, and 6 to 10 percent of all menstruators of reproductive age have the disorder. If this holds true for the general population in the United States, then it is estimated that more than 6.5 million menstruators suffer from endometriosis.53

There is no cure for endometriosis, and there are limited options for treatment. Hormone therapy and some surgery are usually used to reduce the severity of symptoms.54 In very extreme cases of endometriosis—where having your period may be absolutely debilitating—having a hysterectomy (an operation to remove the uterus) is a last resort. However, even then, endometriosis symptoms can reoccur because of tissue lesions that still exist.55

Lowering estrogen levels in the body by using birth control and other drugs also hinders ovulation and will likely compromise fertility, and the painful symptoms of endometriosis will recur as soon as drug usage ceases.56 Fortunately, surgical treatment of endometriosis has been found to improve pregnancy rates for previously infertile women.57 Lowering body fat percentage (eat well and exercise more!) and limiting the amount of alcohol and caffeine you consume can also help decrease estrogen levels, which helps decrease the severity of symptoms.58 If these medical interventions do not improve the condition, there are also alternative methods such as acupuncture, naturopathic medicine, homeopathy, chiropractic treatments, and energy therapies to reduce pain.59

Adenomyosis is a condition more prevalent in older menstruators closer to menopause age, when the endometrial tissue that normally lines the uterus actually grows into the muscular wall of the uterus. This makes periods increasingly painful because the tissue continues to act as it normally would—thickening, breaking down, and bleeding—but while embedded in the uterus. Symptoms include heavier and longer periods with much more cramping, and painful sex. The treatments that exist are anti-inflammatory drugs and hormone therapy.60 The cause of adenomyosis is unknown, and the only known cure is a hysterectomy.61

Uterine fibroids—also known as leiomyomas or myomas—are noncancerous tumors that “grow from the muscle layers” of the uterus.62 Fibroids are not associated with any form of cancer, and their presence does not mean that a menstruator has a higher chance of developing uterine cancer, but they can cause period-related pain and other unfortunate symptoms. Uterine fibroids are surprisingly very common. By the age of thirty-five, about 30 percent of all women have fibroids, and 20 to 80 percent of women will have them by the age of fifty.63

The size of uterine fibroids ranges from undetectable to the naked eye to much bulkier growths that can enlarge or distort the shape of one’s uterus. Most people who have fibroids do not suffer any symptoms besides heavier flows and increased pelvic pressure and pain. However, in some cases—depending on the size, location, and number—fibroids can cause difficulty peeing or pooping, and increased back and leg pains. Because fibroids often don’t cause any particular symptoms, it’s sometimes really hard to tell if you have them. They can be found only if a doctor actively looks with a pelvic exam, ultrasound, or further confirming tests.64

Uterine fibroids are the leading single reason why a hysterectomy—the surgical removal of the uterus—is performed. The hysterectomy is the “second most frequently performed surgical procedure (after cesarean section) for US women who are of reproductive age.”65 More than six hundred thousand hysterectomies are performed every year in the United States alone, and “more than one-third of all women [aged sixty or older] have had a hysterectomy.” And it is estimated that “approximately 20 million American women have had a hysterectomy.”66 There are four different types of hysterectomies, involving partial or total removal of the uterus, cervix, ovaries, and fallopian tubes. There is still a chance of pregnancy when only one ovary or fallopian tube is taken out. However, for a total hysterectomy—which is the removal of the uterus, cervix, both ovaries, and both fallopian tubes—there is absolutely no chance of pregnancy.67

Two other less-invasive surgical procedures that do not involve removing the uterus are called a myomectomy (removes just the fibroids and keeps the uterus intact) and a myolysis (an electrified needle shrinks the fibroids and their blood supply).68 Neither a myomectomy nor a myolysis affects a woman’s fertility, but it is possible that after a myomectomy a doctor will recommend that the person give birth only through a cesarean section.69

Additionally, uterine artery embolization (UAE) is a minimally invasive approach to treating fibroids. In UAE an interventional radiologist uses local anesthesia so that a catheter can be inserted into the uterine artery (which supplies blood to the uterus) through a tiny cut made right at the top of your leg.70 Through this catheter “small plastic or gelatin particles”—called polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)—are pushed into the blood supply. The PVA then “creates a clot that blocks the blood flow to the uterus and fibroids,” which causes the fibroids to “shrink and die.”71

Though any human with a uterus can have uterine fibroids, African American women tend to have more, get them at an earlier age, and suffer from more severe symptoms. Black women are also more likely to experience painful symptoms for longer before seeking any sort of treatment—and studies have shown that it is significantly harder for these women to find valid information on the effects of treatment options.72 African American women are also 2.4 times more likely to have a hysterectomy than a woman from any other group.73 And as women grow older, the risk of developing uterine fibroids decreases overall for most women but not for African American women.74

Lynn Seely is the CEO of Myovant Sciences, a biotechnology company that is working to develop “innovative therapies for heavy menstrual bleeding from uterine fibroids and endometriosis-associated pain.” Companies such as Myovant are striving for a future where menstruators do not have to “suffer in silence, unable to realize their full potential,” but can have their pain recognized and “treated with a pill, instead of invasive surgeries.” Seely says that breaking the silence around menstruation is part of the journey to alleviating intense period pain. Talking about menstruation helps medical professionals diagnose conditions, it raises awareness about the demand for more research into solutions, and most important, it contributes to a future where people feel empowered to “speak openly about their experiences [and] to seek help if needed.”75

More than eight hundred thousand menstruators are diagnosed with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) every year in the United States. PID is “an inflammation of the female reproductive organs” that causes chronic pain around the pelvic area and difficulty with fertility. One in eight women who have been diagnosed with PID have difficulty becoming pregnant.76 PID is usually caused by untreated sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), such as chlamydia and gonorrhea.77 PID may be prevented by reducing STDs—so use condoms!

PID is curable once it is diagnosed. However, there is no treatment to fix the damage already done by the infection to the reproductive system. Once you are treated, you also have a higher chance of getting it again. If PID is not treated early, complications that may arise include the formation of scar tissue surrounding the fallopian tubes, long-term pain, infertility, and even ectopic pregnancies (when a fetus grows outside the womb, often in fallopian tubes).78 Everyday symptoms of the infection include general pain in the lower back and abdominal area, longer and heavier periods, fever, painful sex, and a burning sensation while peeing.79

We as a society need to talk more about periods and about the related conditions, so that menstruators are better able to know their bodies and regulate their own health. We need to create an atmosphere in the medical field (and also with the general public) that encourages finding solutions to painful period-related infections. We need to educate others about these different health risks, and create an environment where menstruators aren’t afraid to ask questions about their periods and talk about their menstrual experiences, so that we can collect more information to actually find solutions and make diagnoses much earlier and more accurately.

We have just begun to tap into the potential of how better understanding menstruation can improve daily life. There is a slowly growing wave of menstruators who are using their menstruation cycles as a way to plan out their social and work calendars. Some people are even relying on their cycles when making life plans, because they are more in touch with how hormones affect them. A good friend of mine, Mara Zepeda, an entrepreneur in Portland, Oregon, introduced me to this concept of planning around periods—which she learned from Miranda Gray’s book, The Optimized Woman: Using Your Menstrual Cycle to Achieve Success and Fulfillment. Mara thinks of her menstrual cycle as having four seasons, each with its own energy, and plans how she works around this—from the number of hours she works or meetings she has scheduled, to how much social time she allocates for herself to tend to relationships. She says this understanding has allowed her to be more in touch with “what type of self-care and support was needed, and what was possible energetically.”80

In order to increase equitable access to menstrual hygiene and education, it is essential that we understand what stands in our way. Our capacity to innovate and find solutions around problems related to menstruation is hindered by our inability to comfortably talk about and understand periods. We still live in a society where simply whispering the word “period” or “menstruation” can trigger a hailstorm of giggles and redden the cheeks of spectators from discomfort and embarrassment. This taboo and stigmatization of menstruation and associated pain creates a status quo that needs to change.

CHAPTER ONE

•

THE BLOODY TRUTH

Periods are powerful. Human life would literally not exist without them. They are what make reproduction possible and keep our wombs ready to bear children, if or when we choose to do that.

The common experience of menstruation connects people all over the world. Think about it: if you were assigned female at birth, most likely you will get your period on a monthly basis for around forty years of your life. It doesn’t matter where you are from, how you identify, or what access to resources you have. And if you don’t get your period during menstruation age, it means that your body is telling you either that you are pregnant or that your health needs attention. Though, it’s also important to know that when birth control is used without breaks, menstruation may stop as well.

To strengthen the way we advocate for periods, we need to understand what a period is in the first place. In the United States we still live in a culture where there is no expectation that we’ll learn about periods. Even when it is taught (in schools, by parents, by friends), it’s often taught in a way that limits our understanding of what we might call the menstrual experience.

Basic sex education—if available—usually starts in the final years of elementary school and continues into middle school. For those of us who have already experienced it, we might have cringe-worthy memories of our teachers holding up bananas or wooden models of penises to demonstrate how to properly roll a condom on. My favorite memory is of when my eighth-grade science teacher took a red condom, blew it up, and shouted, “See? It works for any size!”

My experience with sex education in elementary and middle school was in gender-segregated classrooms. Teachers often shuffle boys into one classroom and girls into another. In the boys’ classroom the health teacher might explain that the boys’ voices are going to get lower, their testicles will descend, and hairs will grow in unfamiliar places on their bodies.

In the other classroom the girls are learning about their bodies too. They will learn about their own hair growth, about the development of boobs, and about hormones and the new emotions that they might start to feel. This might also be the first time periods are brought up in the classroom. The teacher will hold up a tampon and pad and explain what products are available and the basics of how to use them. But the experience of actually menstruating will not be covered. You won’t find out what the blood will actually look like or what to do if you feel extreme pain while menstruating. The teachers won’t tell you what you should do if you stop menstruating suddenly. The option of using sustainable alternatives such as menstrual cups and reusable pads, rather than a typical tampon or pad, will not be discussed.

From the moment the classroom separates into boys and girls, the girls learn to feel shame about openly talking about menstruation, and this prevents future conversations and questions from surfacing. Girls learn that the topic of periods is something you either keep to yourself or you mention only to other girls, in private circles. And boys often don’t formally learn anything about menstruation. They are taught that it isn’t any of their business, that it’s weird to even be curious.

Menstruator or not, you still have to share spaces with many people who are. Everyone, regardless of sex or gender identity, should know what periods are and should feel comfortable talking about them—this is necessary in order to build inclusive and egalitarian communities. So, let’s dive in.

• WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A PERIOD AND A MENSTRUAL CYCLE? •

“Period” and “menstrual cycle” are two terms that are used to indicate the time of the month when the body excretes blood, but the words don’t mean exactly the same thing. The “menstrual cycle” refers to the approximately twenty-eight-day process during which the body prepares for pregnancy. A “period” is just one brief stop in a much larger menstrual cycle.

The diagram above gives us a look into a menstruator’s pelvic area, right between the hips. The two ovaries hold the eggs, and the whole menstrual cycle is directed by two of our hormone friends: estrogen and progesterone.

At the beginning of each cycle, estrogen and progesterone trigger the creation of the endometrium, which is a lining on the inside walls of the uterus. Made of tissue and blood, the endometrium is spongy enough to make a perfect landing place for a fertilized egg. When pregnancy does occur, the uterus is often referred to as the womb.

Ovulation happens when a menstruator’s ovaries release a matured egg about halfway through a menstrual cycle. As you can see from the diagram, in order to get to the uterus, the matured egg travels through the fallopian tubes. The egg basically just sits in the fallopian tube or the uterus and waits, hoping to be fertilized by a sperm cell. Most of the time pregnancy does not occur, which causes the uterine lining to break off from the uterine wall and exit the body through the vaginal canal. This action is what we call a period.

• THE BLOODY TRUTH ABOUT PERIOD BLOOD •

When I first got my period, I was scared. I knew what menstruation was, but no one had ever told me how period blood would look, smell, and feel. So, here it is—the bloody truth in all its glory:

What period blood actually looks like, how it smells, the color, and how much of it comes out will vary across menstrual experiences. There is no “normal” version of menstruation. All bodies are different, so period experiences will also be different. Yes, the menstrual cycle is approximately a twenty-eight-day interval, but the cycle is rarely precisely twenty-eight days—and some menstruators sometimes will bleed between periods.1

On average a menstruator will lose anywhere from five to twelve teaspoons, or about thirty to seventy-two milliliters, of blood in one menstrual cycle.2 Sixty milliliters of blood or more is considered a heavy flow. But how can someone measure the amount of blood? Each regular-size tampon holds about five milliliters of blood;3 so this means that if you are using more than twelve tampons per period that are getting fully soaked, then you should go see a doctor. Another way to figure out how much blood you are expelling is to use menstrual cups, which often have marks for measurement on their sides.

When period flow gets very heavy, more than eighty milliliters per cycle, it’s called menorrhagia, and losing this much blood can cause one to feel tired and short of breath—both of which are symptoms of anemia. Having such a heavy flow is not only a hassle because more period products are needed, but it can also be extremely painful. The opposite of this condition, a very light period of less than twenty-five milliliters of blood lost, is called hypomenorrhea.4 So what causes some of us to have only light spotting once a month, and others to experience prolonged menstrual cycles that involve changing pads multiple times in an hour?

Menstruators who have had children or are in perimenopause (the phase right before menopause) typically have heavier flows because menorrhagia can be caused by hormone imbalance—high estrogen and low progesterone leads to more bleeding and clots (passing more than one per day)—but menorrhagia can occur for a number of different reasons, such as certain medications that interfere with blood clotting, uterine fibroids (benign tumors), and polyps (benign growths).5,6 What can you do to regulate or help lessen the pain of period flow? Use the right products for you, eat well, and exercise in a healthy way.7

The color of period blood can also be anywhere from dark brown or even black to a very vibrant red color. This difference in color does not necessarily have any implication for one’s health when within the red spectrum. The color of the blood is dependent on how long the blood, tissue, or even clots have been exposed to oxygen. It’s similar to how your blood changes color if you cut your skin. When you first start to bleed, the color is this very bright red. After letting the cut heal a bit (hopefully with a bandage and disinfectant), the scab that forms is very dark, almost purple. The color of blood darkens with more exposure to oxygen because the pigment concentrates as the water in the blood evaporates.8 The brighter the period blood, the less time it has been in your uterus. The blood flow tends to get a bit heavier on day two or three of your period, so this is when the color of one’s period blood might become brighter.9

The consistency of period blood is probably what people are most in the dark about. No one really tells you what your period is going to feel like, much less what the actual blood is going to be like. Most of my guy friends assume that period blood is watery, like when you get a bloody nose. Incorrect. Your menstrual blood might be watery some of the time, particularly in the first few cycles or in the final days of your period, but it won’t only be like that—and it might not be like that at all for some menstruators. Since vaginal mucus also comes out during a period, the discharge is sometimes slippery and feels a bit like jelly. It’s also pretty normal for period blood to look a little clumpy, from small blood clots. There is nothing to worry about if any clots appear on a period product or in the toilet. This just means that your body is pushing out the menstrual blood faster than your body can break down the clots. Clots are a concern only if they are the size of a quarter or larger.10

Do not feel embarrassed about how your period blood smells, and definitely don’t try to fix it by douching. Douching and forcibly cleaning out your uterus can actually be very unhealthy because it changes the uterus’s natural acidity. It is totally normal for your vagina and period blood to have distinct odors. In fact, menstrual blood is supposed to have that smell. Some might describe this smell as a bit metallic. It isn’t just blood you’re smelling; it’s also mucus and tissue from the lining, as well as bacteria and other fluids. And the smell is stronger when these things sit in your uterus for longer.

If your vaginal discharge or period blood starts to have a fishy scent, that’s when you should see a doctor. There are some common infections, such as bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis, that are known to have a fishy scent. Luckily, these infections can be easily cured with antibiotics.11 The truth is, after the first few times, you’ll get familiar with your period, and the smell of your own period blood and vaginal discharge will become completely recognizable. So, if you suddenly start to notice that it smells different, then you know to go to the doctor and ask questions.12

Pooping more during your period? Also totally normal. When progesterone levels suddenly drop immediately after your period starts (after reaching maximum production right before), that sort of release can cause your bowels to open up a bit more.13

• WHO MENSTRUATES? •

Menstruation usually starts when a person is between ten and fifteen years old, with the average age of menarche being twelve years old. There is no “correct” age when someone should get their first period, and there are a lot of biological and environmental factors that affect when menarche begins.14 Usually, in the six months leading up to menarche, a menstruator will notice more vaginal discharge than usual.15 Vaginal discharge is absolutely normal: it’s a sort of housekeeping function where glands in the vagina and cervix produce fluids to help carry dead cells and any bacteria out of the body. The discharge can vary in color and texture but is usually a white or cloudy-colored thick paste.16

There are theories about the age at which menarche occurs and what it can tell you about your future and current life, especially since studies have shown that both hormones and stress can influence when you get your period. Some of these theories say that an early first period can signify an unsettled childhood, and that if menarche occurs at either a very young age or a very late age, that can mean a higher chance of heart disease.17 Another observation is that experiencing menarche at a younger age is linked to breast cancer.18 But ultimately the most important thing is that the first period (when blood actually comes out of the vagina) indicates that a menstruator has the ability to get pregnant.

The menstrual career (a term that we’ll use to refer to the years when menstruation happens) extends until menopause occurs. After menopause happens, a person can no longer get pregnant.19 There is no process to determine when a menstruator can expect to experience menopause, but in the United States the average age is fifty-two.20 The process of menopause can be a strenuous one that may involve vaginal dryness, hot flashes and chills, abrupt mood changes, trouble sleeping, lower energy, and so on. Of course, different people will experience different symptoms, but having irregular periods during perimenopause is very common. A menstruator is considered to be in menopause when a full twelve months have passed without a period.21

It is not only women who menstruate. Some transgender men and people who identify as nonbinary or genderqueer (or others) but who were assigned female at birth might still experience periods. For many readers this may be the first time you’ve thought about the intersectionality of gender and periods before, but it is an extremely important discussion to have early on, to ensure that the Menstrual Movement is inclusive of all period experiences. I will admit that in my early days of menstrual activism, I did not consider that anyone other than women could experience menstruation. However, since learning about it, gender inclusivity when talking about periods has become one of my priorities.

It’s important to use language that is inclusive of all menstrual experiences. For transgender men and genderqueer people (and others) who still experience menstruation and have uteruses, vaginas, ovaries, and fallopian tubes, periods can be very difficult—not only because of menstrual health management, but also because menstruation is a reminder that their sex (assigned at birth) does not match their gender identity. As you may have noticed, I avoid using terms such as “feminine hygiene” and “feminine products” in an effort to be gender-inclusive.

• WHEN YOUR PERIOD DOESN’T COME •

The word “menarche” is made up of two Greek words: “men,” which means “month,” and “arche,” which means “beginning.” So the term literally means “the first occurrence of a monthly event.” It is the beginning of something that starts when you’re young and continues through much of your life.

“Amenorrhea” is the word used to describe when menstruation is absent for someone who is of menstruating age—when they have missed three or more of their periods or haven’t gotten their period before the age of fifteen. Amenorrhea is usually caused by pregnancy, breast-feeding, or menopause. When someone gets pregnant, they do not experience menstruation because the uterine lining is needed to cultivate the fertilized egg.22 Amenorrhea can also be caused by a problem with the reproductive organs or unregulated hormone levels, or disruption of normal hormone levels as a result of birth control.23

Periods are sort of magical in the way that they can tell us when our bodies need a bit more attention. For example, I ran for city council in Cambridge, Massachusetts, when I was nineteen years old. Doing so was one of the most exhausting experiences of my life—from how emotionally draining it was to be under scrutiny at all times, to the physical fatigue of canvassing for at least four hours per day.

I did not get my period for the entire duration of my campaign—literally from the week before I announced my candidacy in March, all the way until the day after Election Day, November 8. My doctors could explain my period’s break only in relation to the stress and perhaps increased and abnormal (for me, at least) activity that canvassing so often requires.

• WHAT IS PMS? •

In anticipation of a potential sperm cell that can fertilize the egg, two weeks prior to menstruation, estrogen and progesterone orchestrate premenstrual syndrome, more commonly referred to as PMS. It is not irregular to meet someone who doesn’t fully understand what a period is but is definitely familiar with PMS—especially men who use the term “PMS” to refer to that “time of month” when they perceive women as more emotionally on edge.

Who hasn’t heard jokes about PMS? When I was growing up, boys and girls being moody or overly emotional were called out for being “on their period.” My sisters and I would also tease my mom about menstruating when she had odd cravings or would start randomly crying about things that seemed trivial to us. I heard these jokes on my favorite television shows and in school hallways as boys competed with one another to see who was more “manly.” While all these jokes exacerbate the stigma around periods in a very negative way—by painting periods as something that makes women perhaps less stable and thus less capable—these assumptions are based on very real symptoms of PMS.

PMS symptoms, which affect an estimated 75 percent of menstruators, include “mood swings, tender breasts, food cravings, fatigue, irritability and depression.”24 Other symptoms include social withdrawal, having trouble concentrating, crying spells, heightened anxiety, muscle pain, and so much more. Though the list of potential symptoms is long, most menstruators experience only a few of them and not severely.25 PMS is very normal, and symptoms can be reduced and even stopped with basic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like Advil and Motrin, or basic hormonal therapy like birth control (which can help regulate or healthily stop periods).26

If the PMS symptoms are extreme, even to the point where the menstruator can’t get out of bed, then they could be suffering from a condition such as endometriosis (which we will explore in a bit) or premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). PMDD is a severe form of PMS that induces a lot of pain, like strong menstrual cramps and headaches. Severe PMS like this is difficult to handle every month and can lead to poor mental health—the cramps and negative moods can seriously affect a menstruator’s confidence and perception of their own ability.27

• DOES GETTING YOUR PERIOD HURT? •

If you have to miss something because you have bad cramps, tell someone that is why! The more we legitimize periods and period pain, we will help people think of it as something that happens to everybody, which it does.

—Elizabeth Yuko, sex educator and writer28

As I said, it’s very common to experience some degree of pain during your period. Most of the time it’s perfectly normal and fine, even if it’s unpleasant. At other times the pain can be an indication that something is wrong, so we do need to pay attention. Here are various kinds and causes of menstrual pain. I hope this information doesn’t scare you but rather empowers you to know your body!

MENSTRUAL CRAMPS (DYSMENORRHEA)

Painful menstruation, also known as dysmenorrhea, is the number one cause of absenteeism in menstruating adolescents and in menstruators younger than thirty years old.29 Up to 80 percent of menstruators struggle with varying levels of menstrual pain in their lifetime.30 At least 10 percent of these menstruators are temporarily physically disabled by extreme symptoms.31

Because menstrual cramps are so common, young menstruators often assume it to be a natural part of having your period—even when the cramps are debilitating. While there are no cures for cramps, there are remedies that can reduce the severity of the symptoms, but in order to find the right treatments, menstruators have to speak out about their period experience. As more young women have come forward with their personal stories of feeling incapacitated by menstrual pain, dysmenorrhea has increasingly been recognized as a serious medical condition. It is important to talk about period pain—not only because it may help lead to more menstruators finding effective remedies, but also because severe menstrual cramps could actually be endometriosis, which is much more serious (and, if left untreated, can cause more permanent damage to internal tissue), rather than simply normal cramps.32

Menstrual cramps are caused by chemicals called prostaglandins, which are produced by the uterine lining that grows during the menstrual cycle. These chemicals cause surrounding muscles to contract, triggering sharp pains in the lower abdomen and lower back areas, similar to labor pains. The cramps usually start a few days before menstruation begins and last for up to four days. Other symptoms of dysmenorrhea include “nausea, vomiting, sweating, dizziness, headaches,” and sometimes diarrhea.33 These cramps usually start when puberty begins and will last for around a decade, so younger menstruators are more at risk for painful periods. Cramps also tend to be worse for those who have never given birth or who naturally have heavy flows.34

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as Advil, Motrin, and generic ibuprofen can be used to block the production of prostaglandins—and these drugs are often more effective for period cramps than other basic painkillers, like Tylenol.35 Some menstruators have their own home remedies for preventing painful periods—whether that be taking warm baths or using heating pads or sipping certain favorite decaffeinated teas. Menstrual cramps can also be lessened with a healthier diet that lowers the intake of fat, alcohol, and caffeine; and by engaging in less stressful and more active lifestyles.36

Cramping pain that is caused by a specific condition is called secondary dysmenorrhea, and an estimated 5 to 10 percent of menstruators suffer from these conditions.37 These include endometriosis, uterine fibroids, and pelvic inflammatory disease.38

ENDOMETRIOSIS

Endometriosis is a gynecological disorder and chronic condition that makes menstruation a very painful and difficult process, with heavier flows, extreme fatigue, and chronic pain around the pelvis. Those who suffer from this condition may experience congestive dysmenorrhea, a fancy term for really painful periods, where the pain is a deep, constant severe aching. This intense pain usually begins before and ends after one’s period. While endometriosis can typically occur in menstruators between the ages of fifteen and forty-four, the symptoms are more apparent for women in their thirties and forties.39 Endometriosis may also cause deep dyspareunia, which means that sex is extremely painful—usually triggered by pressure on the cervix. Even going to the bathroom might be painful.40,41 And it is not guaranteed that symptoms of endometriosis will stop after menopause, when menstruation no longer occurs.42

Endometriosis is a condition in which the uterine lining (the endometrium) grows outside the uterus.43 The endometrial tissue will act normally and will thicken, break down, and bleed as it usually does during menstruation. However, when the tissue isn’t in the uterus, there is nowhere for the blood to exit the body, so it gets trapped. This irritates the surrounding body tissue and can cause the tissue to scar and stick together. Too much adhesion of the tissue can even cause the pelvic anatomy to distort (like the colon sticks to the back of the uterus or an ovary).44 In some cases of endometriosis, endometriomas (ovarian cysts made of endometrial tissue) may form.45 These cysts are associated with heightened pain during menstruation.46

Endometriosis is also directly linked to infertility. A study conducted in 2009 found that about 47 percent of infertile menstruators had endometriosis.47 Unfortunately, the condition never disappears once you have it, but the symptoms may be less severe at certain points.48 Most symptoms will subside when menopause occurs, because endometriosis is an “estrogen-dependent disease.”49

Endometriosis is extremely hard to diagnose because many of its symptoms are extreme versions of a usual menstrual experience. On average, someone with endometriosis goes seven years before any formal diagnosis.50 The only way to diagnose endometriosis is with a laparoscopic inspection of the pelvis—an invasive procedure that uses a video camera to examine internal organs.51 Another issue that may prevent a diagnosis is the fact that period pain is so common and there is no “normal” level of pain. Many menstruators underestimate the severity of their condition, and it’s also difficult for doctors to gauge when period pain becomes serious enough to demand the laparoscopic surgery.52 In 2011 a study found that 11 percent of all menstruators who had not already been diagnosed have endometriosis, and 6 to 10 percent of all menstruators of reproductive age have the disorder. If this holds true for the general population in the United States, then it is estimated that more than 6.5 million menstruators suffer from endometriosis.53

There is no cure for endometriosis, and there are limited options for treatment. Hormone therapy and some surgery are usually used to reduce the severity of symptoms.54 In very extreme cases of endometriosis—where having your period may be absolutely debilitating—having a hysterectomy (an operation to remove the uterus) is a last resort. However, even then, endometriosis symptoms can reoccur because of tissue lesions that still exist.55

Lowering estrogen levels in the body by using birth control and other drugs also hinders ovulation and will likely compromise fertility, and the painful symptoms of endometriosis will recur as soon as drug usage ceases.56 Fortunately, surgical treatment of endometriosis has been found to improve pregnancy rates for previously infertile women.57 Lowering body fat percentage (eat well and exercise more!) and limiting the amount of alcohol and caffeine you consume can also help decrease estrogen levels, which helps decrease the severity of symptoms.58 If these medical interventions do not improve the condition, there are also alternative methods such as acupuncture, naturopathic medicine, homeopathy, chiropractic treatments, and energy therapies to reduce pain.59

ADENOMYOSIS

Adenomyosis is a condition more prevalent in older menstruators closer to menopause age, when the endometrial tissue that normally lines the uterus actually grows into the muscular wall of the uterus. This makes periods increasingly painful because the tissue continues to act as it normally would—thickening, breaking down, and bleeding—but while embedded in the uterus. Symptoms include heavier and longer periods with much more cramping, and painful sex. The treatments that exist are anti-inflammatory drugs and hormone therapy.60 The cause of adenomyosis is unknown, and the only known cure is a hysterectomy.61

UTERINE FIBROIDS

Uterine fibroids—also known as leiomyomas or myomas—are noncancerous tumors that “grow from the muscle layers” of the uterus.62 Fibroids are not associated with any form of cancer, and their presence does not mean that a menstruator has a higher chance of developing uterine cancer, but they can cause period-related pain and other unfortunate symptoms. Uterine fibroids are surprisingly very common. By the age of thirty-five, about 30 percent of all women have fibroids, and 20 to 80 percent of women will have them by the age of fifty.63

The size of uterine fibroids ranges from undetectable to the naked eye to much bulkier growths that can enlarge or distort the shape of one’s uterus. Most people who have fibroids do not suffer any symptoms besides heavier flows and increased pelvic pressure and pain. However, in some cases—depending on the size, location, and number—fibroids can cause difficulty peeing or pooping, and increased back and leg pains. Because fibroids often don’t cause any particular symptoms, it’s sometimes really hard to tell if you have them. They can be found only if a doctor actively looks with a pelvic exam, ultrasound, or further confirming tests.64

Uterine fibroids are the leading single reason why a hysterectomy—the surgical removal of the uterus—is performed. The hysterectomy is the “second most frequently performed surgical procedure (after cesarean section) for US women who are of reproductive age.”65 More than six hundred thousand hysterectomies are performed every year in the United States alone, and “more than one-third of all women [aged sixty or older] have had a hysterectomy.” And it is estimated that “approximately 20 million American women have had a hysterectomy.”66 There are four different types of hysterectomies, involving partial or total removal of the uterus, cervix, ovaries, and fallopian tubes. There is still a chance of pregnancy when only one ovary or fallopian tube is taken out. However, for a total hysterectomy—which is the removal of the uterus, cervix, both ovaries, and both fallopian tubes—there is absolutely no chance of pregnancy.67

Two other less-invasive surgical procedures that do not involve removing the uterus are called a myomectomy (removes just the fibroids and keeps the uterus intact) and a myolysis (an electrified needle shrinks the fibroids and their blood supply).68 Neither a myomectomy nor a myolysis affects a woman’s fertility, but it is possible that after a myomectomy a doctor will recommend that the person give birth only through a cesarean section.69

Additionally, uterine artery embolization (UAE) is a minimally invasive approach to treating fibroids. In UAE an interventional radiologist uses local anesthesia so that a catheter can be inserted into the uterine artery (which supplies blood to the uterus) through a tiny cut made right at the top of your leg.70 Through this catheter “small plastic or gelatin particles”—called polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)—are pushed into the blood supply. The PVA then “creates a clot that blocks the blood flow to the uterus and fibroids,” which causes the fibroids to “shrink and die.”71

Though any human with a uterus can have uterine fibroids, African American women tend to have more, get them at an earlier age, and suffer from more severe symptoms. Black women are also more likely to experience painful symptoms for longer before seeking any sort of treatment—and studies have shown that it is significantly harder for these women to find valid information on the effects of treatment options.72 African American women are also 2.4 times more likely to have a hysterectomy than a woman from any other group.73 And as women grow older, the risk of developing uterine fibroids decreases overall for most women but not for African American women.74

Lynn Seely is the CEO of Myovant Sciences, a biotechnology company that is working to develop “innovative therapies for heavy menstrual bleeding from uterine fibroids and endometriosis-associated pain.” Companies such as Myovant are striving for a future where menstruators do not have to “suffer in silence, unable to realize their full potential,” but can have their pain recognized and “treated with a pill, instead of invasive surgeries.” Seely says that breaking the silence around menstruation is part of the journey to alleviating intense period pain. Talking about menstruation helps medical professionals diagnose conditions, it raises awareness about the demand for more research into solutions, and most important, it contributes to a future where people feel empowered to “speak openly about their experiences [and] to seek help if needed.”75

PELVIC INFLAMMATORY DISEASE (PID)

More than eight hundred thousand menstruators are diagnosed with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) every year in the United States. PID is “an inflammation of the female reproductive organs” that causes chronic pain around the pelvic area and difficulty with fertility. One in eight women who have been diagnosed with PID have difficulty becoming pregnant.76 PID is usually caused by untreated sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), such as chlamydia and gonorrhea.77 PID may be prevented by reducing STDs—so use condoms!

PID is curable once it is diagnosed. However, there is no treatment to fix the damage already done by the infection to the reproductive system. Once you are treated, you also have a higher chance of getting it again. If PID is not treated early, complications that may arise include the formation of scar tissue surrounding the fallopian tubes, long-term pain, infertility, and even ectopic pregnancies (when a fetus grows outside the womb, often in fallopian tubes).78 Everyday symptoms of the infection include general pain in the lower back and abdominal area, longer and heavier periods, fever, painful sex, and a burning sensation while peeing.79

We as a society need to talk more about periods and about the related conditions, so that menstruators are better able to know their bodies and regulate their own health. We need to create an atmosphere in the medical field (and also with the general public) that encourages finding solutions to painful period-related infections. We need to educate others about these different health risks, and create an environment where menstruators aren’t afraid to ask questions about their periods and talk about their menstrual experiences, so that we can collect more information to actually find solutions and make diagnoses much earlier and more accurately.

We have just begun to tap into the potential of how better understanding menstruation can improve daily life. There is a slowly growing wave of menstruators who are using their menstruation cycles as a way to plan out their social and work calendars. Some people are even relying on their cycles when making life plans, because they are more in touch with how hormones affect them. A good friend of mine, Mara Zepeda, an entrepreneur in Portland, Oregon, introduced me to this concept of planning around periods—which she learned from Miranda Gray’s book, The Optimized Woman: Using Your Menstrual Cycle to Achieve Success and Fulfillment. Mara thinks of her menstrual cycle as having four seasons, each with its own energy, and plans how she works around this—from the number of hours she works or meetings she has scheduled, to how much social time she allocates for herself to tend to relationships. She says this understanding has allowed her to be more in touch with “what type of self-care and support was needed, and what was possible energetically.”80

In order to increase equitable access to menstrual hygiene and education, it is essential that we understand what stands in our way. Our capacity to innovate and find solutions around problems related to menstruation is hindered by our inability to comfortably talk about and understand periods. We still live in a society where simply whispering the word “period” or “menstruation” can trigger a hailstorm of giggles and redden the cheeks of spectators from discomfort and embarrassment. This taboo and stigmatization of menstruation and associated pain creates a status quo that needs to change.

Recenzii

"A must-read for anyone who wants to make change at the state and national levels.”

"If you’re looking for a way to turn your anger about gender inequality into action, this book is a must read. You’ll learn a great deal about menstrual inequities and the intersectional impacts created because of our failure to address them. This is a how-to handbook on what you can do to change that."

"Period Power, much like it’s author Nadya Okamoto, is insightful and impossible to ignore. I’ve found empowerment in her prose, and inspiration in her lack of shame. This book teaches adults and youths alike to be unapologetically proud to bleed. If someone you love has a vagina then Period Power is required reading."

*“[T]ruly intersectional and…a useful guide for activists inspired by this work…A smart, honest, and comprehensive education on movement building and menstrual rights.”

"Okamoto intends to end menstrual stigma and taboo--full stop. This book is a game-changer for anyone who has ever had a period—or knows anyone who has had or will have one."

"A true manifesto, Period Power is the book my fourteen-year-old self wished for and the one my adult self desperately needed."

"Nadya Okamoto has written a quintessential manifesto for the leader in all of us. Her infectious passion, wit, and piercing intelligence will inspire you to rise into your bravest self. Moreover, this book and her voice have the power to help us learn self-love and respect, in a deep, authentic, lasting way. Not only will this book change your life, it will change the world. Nadya Okamoto is a revolution."

"Period Power is the latest in the growing list of gifts that author and activist Nadya Okamoto has bestowed on this world. In her book one can glean her dedication to ending period stigma and her effervescent and infectious enthusiasm for human rights. Period Power is a necessary and empowering take on menstruation that everyone should add to their personal library."

"Period Power is a must-read for women and men to educate themselves both on the history and stigma of menstruation, period policy, and its representation in the media -- but also concrete action items for making a difference. Nadya's ability to combine knowledge with action is what makes Period Power so powerful."

"Nadya Okamoto’s Period Power takes a brave, necessary look at menstruation. Filled with both personal narratives and historical context, this book should be required reading for not just young students around puberty age, but adults as well. We must, as a society, reframe and relearn how we discuss and understand bleeding, and Okamoto’s book is a necessary first step."

"Nadya is a paradigm changer. Period Power exposes the true cost of a society too embarrassed to talk about this universal issue, but also offers a plan of action that is humanizing to the individual and grand in enough in scope to change our culture forever."

"Nadya's spirit and period positivity explodes throughout this book. Reading about the menstrual movement through the lens of a young menstruator is refreshing and truly gives me hope for the future."

"This book is very interesting as it addresses an important issue related to the power of women. I hugely recommend you read it and learn its wisdom."

"Nadya Okamato's book, Period Power, is filled with information crucial to being a good person in this world. Periods affect more than half of the world's population. If this blurb makes you uncomfortable because I'm talking about menstruation, you NEED to read this book. Change the cycle."

“Okamoto writes with passion and power, her voice clear and straightforward…[an] empowering book.”

"Since the beginning of time, women have been made to feel ashamed of their bodies and their periods. It has even been a barrier to women and girls ability to have and seek access to education and or employment. Its time we remove the stigma and create space for honest and informative conversation about menstruation, one that doesn’t leave anyone out. Period Power helps us get there.”

"Nadya is a powerhouse helping to lead the menstrual movement in this country. This book is a must read for anyone who sees the need to smash the shame around periods."

"A must-read for anyone committed to gender equity. Nadya Okamoto educates and activates in her personal manifesto aimed at getting rid of the stigma around periods and beginning honest conversations. Her mission includes changing policies which cause menstruators to experience financial burdens and social separation based on a normal life cycle event for half of the world's population. It is well-past time to talk and act, and Nadya's book is a great anthem to organize the movement."

"If you’re looking for a way to turn your anger about gender inequality into action, this book is a must read. You’ll learn a great deal about menstrual inequities and the intersectional impacts created because of our failure to address them. This is a how-to handbook on what you can do to change that."

"Period Power, much like it’s author Nadya Okamoto, is insightful and impossible to ignore. I’ve found empowerment in her prose, and inspiration in her lack of shame. This book teaches adults and youths alike to be unapologetically proud to bleed. If someone you love has a vagina then Period Power is required reading."

*“[T]ruly intersectional and…a useful guide for activists inspired by this work…A smart, honest, and comprehensive education on movement building and menstrual rights.”

"Okamoto intends to end menstrual stigma and taboo--full stop. This book is a game-changer for anyone who has ever had a period—or knows anyone who has had or will have one."

"A true manifesto, Period Power is the book my fourteen-year-old self wished for and the one my adult self desperately needed."

"Nadya Okamoto has written a quintessential manifesto for the leader in all of us. Her infectious passion, wit, and piercing intelligence will inspire you to rise into your bravest self. Moreover, this book and her voice have the power to help us learn self-love and respect, in a deep, authentic, lasting way. Not only will this book change your life, it will change the world. Nadya Okamoto is a revolution."