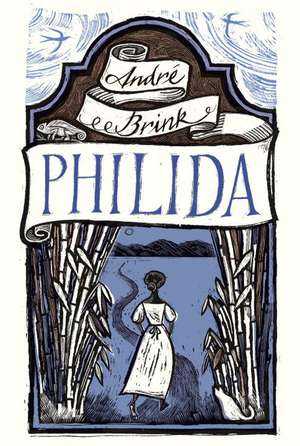

Philida

Autor Andre Brinken Limba Engleză Paperback – 4 feb 2013

In Philida, longlisted for the Man Booker Prize, André Brink—“one of South Africa's greatest novelists” (The Telegraph)—gives us his most powerful novel yet; the truly unforgettable story of a female slave, and her fierce determination to survive and to be free.

It is 1832 in South Africa, the year before slavery is abolished and the slaves are emancipated. Philida is the mother of four children by Francois Brink, the son of her master. When Francois’s father orders him to marry a woman from a prominent Cape Town family, Francois reneges on his promise to give Philida her freedom, threatening instead to sell her to new owners in the harsh country up north.

Here is the remarkable story—based on individuals connected to the author’s family—of a fiercely independent woman who will settle for nothing and for no one. Unwilling to accept the future that lies ahead of her, Philida continues to test the limits and lodges a complaint against the Brink family. Then she sets off on a journey—from the southernmost reaches of the Cape, across a great wilderness, to the far north of the country—in order to reclaim her soul.

Preț: 84.76 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 127

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.23€ • 16.74$ • 13.45£

16.23€ • 16.74$ • 13.45£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345805034

ISBN-10: 0345805038

Pagini: 310

Dimensiuni: 138 x 209 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0345805038

Pagini: 310

Dimensiuni: 138 x 209 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

Extras

Excerpted from Chapter One

On Saturday 17 November 1832, after following the Elephant Trail that runs between the Village of Franschhoek, past the Farm Zandvliet to the small Town of Stellenbosch near Cape Town, the young Slave Woman Philida arrives at the Drostdy with its tall white Pillars, where she is directed to the Office of the Slave Protector, Mijnheer Lindenberg, to lodge a Complaint against her Owner Cornelis Brink and his Son Francois Gerhard Jacob Brink

Here come shit. Just one look, and I can see it coming. Here I walk all this way and God know that is bad enough, what with the child in the abbadoek on my back, and now there’s no turning back, it’s just straight on to hell and gone. This is the man I got to talk to if I want to lay a charge, they tell me, this Grootbaas who is so tall and white and thin and bony, with deep furrows in his forehead, like a badly ploughed wheat field, and a nose like a sweet potato that has grown past itself.

It’s a long story. First he want to find out everything about me, and it’s one question after another. Who am I? Where do I come from? What is the name of my Baas? What is the name of the farm? For how long I been working there? Did I get a pass for coming here? When did I leave and how long did I walk? Where did I sleep last night? What do I think is going to happen to me when I get home again? And every time I say something, he first write it down in his big book with those knobbly hands and his long white fingers. These people got a thing about writing everything down. Just look at the back pages of the black Bible that belong to Oubaas Cornelis Brink, that’s Francois Gerhard Jacob’s father.

While the Grootbaas is writing I keep watching him closely. There’s something second-hand about the man, like a piece of knitting gone wrong that had to be done over, but badly, not very smoothly. I can say that because I know about knitting. On his nose sit a pair of thick glasses like a bat with open wings, but he look at me over them, not through them. His long hands keep busy all the time. Writing, and dipping the long feather in the ink, and sprinkling fine sand on the thick paper, and shifting his papers this way and that on top of the table that is really too low for him because he is so tall. He is sitting, I keep standing, that is how it’s got to be.

In the beginning I feel scared, my throat is tight. But after the second or third question I start feeling better. All I can think of is: If it was me that was knitting you, you’d look a bit better, but now whoever it was that knitted you, did not cast you off right. Still, I don’t say anything. In this place it’s only him and me and I don’t want to get on his wrong side. I got to tell him everything, and that is exactly what I mean to do today, without keeping anything back.

He ask me: When did Francois Brink first... I mean, when was it that the two of you began to... you know what I’m talking about?

Eight years ago.

You sure about that? How can you be so sure?

Ja, it is eight years, I tell you, my Grootbaas. I remember it very clearly because that was the winter when Oubaas Cornelis take the lot of us in to the Caab to see the man they hanged, that slave Abraham, on the Castle gallows. And it was after we come home from there, to the farm Zandvliet, that it begin between Frans and me.

How did it begin? What happened?

It was a bad day for me, Grootbaas. Everything that happen in the Caab, in front of the Castle. The man they hang. Two times, because the first time the rope break, and I remember how the man keep dancing at the end of the rope round his neck, and how his thing get all big and stiff and start to spit.

What do you mean, his thing?

His man-thing, Grootbaas, what else? I hear the people talking about how it sometimes happen when a man is hanged, but it is the first time I see it for myself, and I never want to see it again.

And you said that when you came back on the farm...?

Yes, that was when. We first come past the old sow in the sty, the old fat-arse pig they call Hamboud. The Oubaas say many times before that he want to slaughter her because she is so blarry useless, but the Ounooi keep on saying she must stay here so her big arse can grow even bigger and fatter. And afterwards, when we get home, we come past the four horses in the stable, and the two good-for-nothing donkeys, and then the stupid trassie hen that Ounooi Janna call Zelda after her aunt that skinder so much, the hen that don’t know if she is a cock or a hen and that can never manage to lay an egg herself but always go cackling like a mad thing whenever some other hen on the farm lay one. And then in the late afternoon when we are all back on the farm where we belong I first go to Ouma Nella, her full name is Petronella, but to me she is always just Ouma Nella.

And what happened then? ask the tall bony man, beginning to sound impatient.

So I tell him: Then Frans take me with him, away from the longhouse, through the vineyard where the old cemetery is. Down to where the bamboo copse make its deep, dark shade in the elbow of the river, that’s the Dwars River that run across the farm, and there I begin to cry for the first time and that is when Frans ߝ

You mean Baas Frans, the tall bony man remind me.

Yes, Baas Frans he take me to where the bamboo copse close up all around you, and when he see me crying, he get so hot that his thing also jump up, just like the dead man on the gallows, and that is when he get onto me to ride me.

Behind the dusty thick glasses the man’s deep eyes seem to be looking right into me as he ask: Yes, and what did he do then?

I can feel myself going blunt inside, but I know I can’t stop now, so I bite on my teeth and tell him: He do what a man do with a woman.

And what would that be?

I’m sure the Grootbaas will know about that.

He say: I want to know exactly what he did.

He take me.

How did he take you? I have to know all the particulars.

The law demands that I must find out everything that happened. So that it can all be written down very precisely in this book.

I tell him: He naai me.

The tall thin man with the bald head give a cough, as if his spit is now dried up. After a while he ask: Did you resist?

Grootbaas, in the beginning I try to, but that is when Frans begin to talk to me very nicely and tell me I mustn’t be scared, he won’t hurt me, he just want to make me happy. If I will let him push into me, then he will make sure to buy me my freedom when the time is right, that is what he promise me before the LordGod of the Bible, he say he himself will buy freedom for me. But I remember thinking, how can it be that a thing like freedom can hurt one so bad? Because it was my first time and he didn’t act very gentle with me, he was too hasty, I think it was his first time too.

And then what happened?

When he finish, he get up again and tie the riem of his breeches.

It is just as well the man don’t give me much time to think, because the questions start coming again and they getting more and more difficult.

Philida, I want to know what happened afterwards? ask the man with the ploughed field on his forehead. Did you... I mean, were there any consequences to the intercourse you had in the bamboo copse?

I don’t know about that intercourse thing and the consequences, Grootbaas.

This thing you did in the bamboo place. Did it lead to anything? He getting very red in the face. What you did together in that bamboo place...? Did anything happen inside you ߝ to your body?

Not right away, Grootbaas. Only after he lie with me a few times, I start to swell.

How many times?

Many times, Grootbaas.

Two times? Three times? Ten? Twenty?

I fold my hands around my shoulders. And once again I say: Many times, Grootbaas.

Unexpectedly he ask: Was he the first man that was with you?

I just shake my head because I don’t feel like answering. I already told him mos it was my first time.

He change the question a little bit: Have you had a lot of men?

I tell him, It’s only Baas Frans I come to complain about.

Look, if you have a complaint, you’ve got to tell us everything now. Otherwise you’re wasting our time.

Once again I say: It’s just about Baas Frans that I am here.

Did he hurt you?

No, Grootbaas. It was a bit difficult but I can’t say it hurt me too bad. I had badder things happen to me.

Then what are you complaining about?

Because he take me and he promise me things and now he is going away from me.

What did he promise you?

He say he will give me my freedom.

What did he mean when he said he would give you your freedom? He say he will buy me freedom from the Landdrost. From the Govment. But now instead of buying my freedom he want going away from me.

How is he going away from you?

They say he want to marry a white woman. Not a slave or a Khoe but one of his own kind. So now he want to sell me upcountry.

How do you know that?

I hear him talking to the Ounooi about it. They want to put me up on auction.

Why would they want to do that?

Because they want to take my children away from the farm before the white woman come to live here.

What can you tell me about your children?

That’s mos why I am here, Grootbaas.

How many children do you have?

There is two left, but there was four altogether.

What happened to the other two?

I think by myself: Now it is coming. But after a while I just say: They die when they are small. The first one didn’t have a name yet and the second one was Mamie, but she only lived three months, then she also went.

Who is their father?

Frans and I made them.

Baas Frans?

Baas Frans.

He keep on asking: And the two who are still alive? Where are they?

One is at Zandvliet where we made them. She’s Lena. My Ouma Nella look after her. The last one is this one I bring on my back with me.

For some time he say nothing more. Then he get in a hurry and he ask: When did the other two die?

I don’t look at him. All I can say is: When they was small. One was only three months old.

And the other one?

I have nothing to say about the first one.

Why not?

He die too soon.

He look hard at me, then he sigh. All right, he say. What can you tell me about this one you brought with you?

I don’t say anything. I just turn sideways so that he can see the child in the doek on my back.

I tell the man: He is my youngest. He was born only three months ago. His name is Willempie.

And you say it is your Baas Francois’s child?

Yes, that is the truth, before the LordGod.

Can you prove it?

I ask him: How can I prove a thing like that?

If you cannot prove it I cannot write it in my book.

The Grootbaas must believe me.

To believe something, he says, does not make it true.

Grootbaas, I say, there are things about you that I also cannot see, but I believe they are there and that make them true.

He laugh and I can hear it is not a good laugh. He ask: What you talking about?

It is getting more difficult to breathe, but I know I have no choice and so I ask: Will the Grootbaas give me permission to say it?

He say: Look, we’re getting nowhere like this. So all right then, I give you permission.

I nod and look straight at him and I say: Thank you, my Grootbaas. Then I shall take that permission and say to the Grootbaas that I am speaking of the thing on which the Grootbaas is sitting.

Are you talking about my chair?

I am talking about the Grootbaas’s poephol. That is, his arsehole.

I see him turning red first and then a deep, almost black purple. He pant like a man that climb up a steep hill.

Bladdy meid! he say. Are you looking for trouble?

I am not looking for trouble, Grootbaas, and I hope I won’t find any.

For God’s sake, then say it and have done with it.

Then I shall say it with the permission the Grootbaas give me.

Well, what is it?

I just want to say, that thing the Grootbaas is sitting on: I never seen it and with the help of the LordGod I hope I never will. But I know it is there and I believe it, and so it is true. And it is the same with my children. I know Frans made them.

On Saturday 17 November 1832, after following the Elephant Trail that runs between the Village of Franschhoek, past the Farm Zandvliet to the small Town of Stellenbosch near Cape Town, the young Slave Woman Philida arrives at the Drostdy with its tall white Pillars, where she is directed to the Office of the Slave Protector, Mijnheer Lindenberg, to lodge a Complaint against her Owner Cornelis Brink and his Son Francois Gerhard Jacob Brink

Here come shit. Just one look, and I can see it coming. Here I walk all this way and God know that is bad enough, what with the child in the abbadoek on my back, and now there’s no turning back, it’s just straight on to hell and gone. This is the man I got to talk to if I want to lay a charge, they tell me, this Grootbaas who is so tall and white and thin and bony, with deep furrows in his forehead, like a badly ploughed wheat field, and a nose like a sweet potato that has grown past itself.

It’s a long story. First he want to find out everything about me, and it’s one question after another. Who am I? Where do I come from? What is the name of my Baas? What is the name of the farm? For how long I been working there? Did I get a pass for coming here? When did I leave and how long did I walk? Where did I sleep last night? What do I think is going to happen to me when I get home again? And every time I say something, he first write it down in his big book with those knobbly hands and his long white fingers. These people got a thing about writing everything down. Just look at the back pages of the black Bible that belong to Oubaas Cornelis Brink, that’s Francois Gerhard Jacob’s father.

While the Grootbaas is writing I keep watching him closely. There’s something second-hand about the man, like a piece of knitting gone wrong that had to be done over, but badly, not very smoothly. I can say that because I know about knitting. On his nose sit a pair of thick glasses like a bat with open wings, but he look at me over them, not through them. His long hands keep busy all the time. Writing, and dipping the long feather in the ink, and sprinkling fine sand on the thick paper, and shifting his papers this way and that on top of the table that is really too low for him because he is so tall. He is sitting, I keep standing, that is how it’s got to be.

In the beginning I feel scared, my throat is tight. But after the second or third question I start feeling better. All I can think of is: If it was me that was knitting you, you’d look a bit better, but now whoever it was that knitted you, did not cast you off right. Still, I don’t say anything. In this place it’s only him and me and I don’t want to get on his wrong side. I got to tell him everything, and that is exactly what I mean to do today, without keeping anything back.

He ask me: When did Francois Brink first... I mean, when was it that the two of you began to... you know what I’m talking about?

Eight years ago.

You sure about that? How can you be so sure?

Ja, it is eight years, I tell you, my Grootbaas. I remember it very clearly because that was the winter when Oubaas Cornelis take the lot of us in to the Caab to see the man they hanged, that slave Abraham, on the Castle gallows. And it was after we come home from there, to the farm Zandvliet, that it begin between Frans and me.

How did it begin? What happened?

It was a bad day for me, Grootbaas. Everything that happen in the Caab, in front of the Castle. The man they hang. Two times, because the first time the rope break, and I remember how the man keep dancing at the end of the rope round his neck, and how his thing get all big and stiff and start to spit.

What do you mean, his thing?

His man-thing, Grootbaas, what else? I hear the people talking about how it sometimes happen when a man is hanged, but it is the first time I see it for myself, and I never want to see it again.

And you said that when you came back on the farm...?

Yes, that was when. We first come past the old sow in the sty, the old fat-arse pig they call Hamboud. The Oubaas say many times before that he want to slaughter her because she is so blarry useless, but the Ounooi keep on saying she must stay here so her big arse can grow even bigger and fatter. And afterwards, when we get home, we come past the four horses in the stable, and the two good-for-nothing donkeys, and then the stupid trassie hen that Ounooi Janna call Zelda after her aunt that skinder so much, the hen that don’t know if she is a cock or a hen and that can never manage to lay an egg herself but always go cackling like a mad thing whenever some other hen on the farm lay one. And then in the late afternoon when we are all back on the farm where we belong I first go to Ouma Nella, her full name is Petronella, but to me she is always just Ouma Nella.

And what happened then? ask the tall bony man, beginning to sound impatient.

So I tell him: Then Frans take me with him, away from the longhouse, through the vineyard where the old cemetery is. Down to where the bamboo copse make its deep, dark shade in the elbow of the river, that’s the Dwars River that run across the farm, and there I begin to cry for the first time and that is when Frans ߝ

You mean Baas Frans, the tall bony man remind me.

Yes, Baas Frans he take me to where the bamboo copse close up all around you, and when he see me crying, he get so hot that his thing also jump up, just like the dead man on the gallows, and that is when he get onto me to ride me.

Behind the dusty thick glasses the man’s deep eyes seem to be looking right into me as he ask: Yes, and what did he do then?

I can feel myself going blunt inside, but I know I can’t stop now, so I bite on my teeth and tell him: He do what a man do with a woman.

And what would that be?

I’m sure the Grootbaas will know about that.

He say: I want to know exactly what he did.

He take me.

How did he take you? I have to know all the particulars.

The law demands that I must find out everything that happened. So that it can all be written down very precisely in this book.

I tell him: He naai me.

The tall thin man with the bald head give a cough, as if his spit is now dried up. After a while he ask: Did you resist?

Grootbaas, in the beginning I try to, but that is when Frans begin to talk to me very nicely and tell me I mustn’t be scared, he won’t hurt me, he just want to make me happy. If I will let him push into me, then he will make sure to buy me my freedom when the time is right, that is what he promise me before the LordGod of the Bible, he say he himself will buy freedom for me. But I remember thinking, how can it be that a thing like freedom can hurt one so bad? Because it was my first time and he didn’t act very gentle with me, he was too hasty, I think it was his first time too.

And then what happened?

When he finish, he get up again and tie the riem of his breeches.

It is just as well the man don’t give me much time to think, because the questions start coming again and they getting more and more difficult.

Philida, I want to know what happened afterwards? ask the man with the ploughed field on his forehead. Did you... I mean, were there any consequences to the intercourse you had in the bamboo copse?

I don’t know about that intercourse thing and the consequences, Grootbaas.

This thing you did in the bamboo place. Did it lead to anything? He getting very red in the face. What you did together in that bamboo place...? Did anything happen inside you ߝ to your body?

Not right away, Grootbaas. Only after he lie with me a few times, I start to swell.

How many times?

Many times, Grootbaas.

Two times? Three times? Ten? Twenty?

I fold my hands around my shoulders. And once again I say: Many times, Grootbaas.

Unexpectedly he ask: Was he the first man that was with you?

I just shake my head because I don’t feel like answering. I already told him mos it was my first time.

He change the question a little bit: Have you had a lot of men?

I tell him, It’s only Baas Frans I come to complain about.

Look, if you have a complaint, you’ve got to tell us everything now. Otherwise you’re wasting our time.

Once again I say: It’s just about Baas Frans that I am here.

Did he hurt you?

No, Grootbaas. It was a bit difficult but I can’t say it hurt me too bad. I had badder things happen to me.

Then what are you complaining about?

Because he take me and he promise me things and now he is going away from me.

What did he promise you?

He say he will give me my freedom.

What did he mean when he said he would give you your freedom? He say he will buy me freedom from the Landdrost. From the Govment. But now instead of buying my freedom he want going away from me.

How is he going away from you?

They say he want to marry a white woman. Not a slave or a Khoe but one of his own kind. So now he want to sell me upcountry.

How do you know that?

I hear him talking to the Ounooi about it. They want to put me up on auction.

Why would they want to do that?

Because they want to take my children away from the farm before the white woman come to live here.

What can you tell me about your children?

That’s mos why I am here, Grootbaas.

How many children do you have?

There is two left, but there was four altogether.

What happened to the other two?

I think by myself: Now it is coming. But after a while I just say: They die when they are small. The first one didn’t have a name yet and the second one was Mamie, but she only lived three months, then she also went.

Who is their father?

Frans and I made them.

Baas Frans?

Baas Frans.

He keep on asking: And the two who are still alive? Where are they?

One is at Zandvliet where we made them. She’s Lena. My Ouma Nella look after her. The last one is this one I bring on my back with me.

For some time he say nothing more. Then he get in a hurry and he ask: When did the other two die?

I don’t look at him. All I can say is: When they was small. One was only three months old.

And the other one?

I have nothing to say about the first one.

Why not?

He die too soon.

He look hard at me, then he sigh. All right, he say. What can you tell me about this one you brought with you?

I don’t say anything. I just turn sideways so that he can see the child in the doek on my back.

I tell the man: He is my youngest. He was born only three months ago. His name is Willempie.

And you say it is your Baas Francois’s child?

Yes, that is the truth, before the LordGod.

Can you prove it?

I ask him: How can I prove a thing like that?

If you cannot prove it I cannot write it in my book.

The Grootbaas must believe me.

To believe something, he says, does not make it true.

Grootbaas, I say, there are things about you that I also cannot see, but I believe they are there and that make them true.

He laugh and I can hear it is not a good laugh. He ask: What you talking about?

It is getting more difficult to breathe, but I know I have no choice and so I ask: Will the Grootbaas give me permission to say it?

He say: Look, we’re getting nowhere like this. So all right then, I give you permission.

I nod and look straight at him and I say: Thank you, my Grootbaas. Then I shall take that permission and say to the Grootbaas that I am speaking of the thing on which the Grootbaas is sitting.

Are you talking about my chair?

I am talking about the Grootbaas’s poephol. That is, his arsehole.

I see him turning red first and then a deep, almost black purple. He pant like a man that climb up a steep hill.

Bladdy meid! he say. Are you looking for trouble?

I am not looking for trouble, Grootbaas, and I hope I won’t find any.

For God’s sake, then say it and have done with it.

Then I shall say it with the permission the Grootbaas give me.

Well, what is it?

I just want to say, that thing the Grootbaas is sitting on: I never seen it and with the help of the LordGod I hope I never will. But I know it is there and I believe it, and so it is true. And it is the same with my children. I know Frans made them.

Notă biografică

André Brink is the author of numerous novels, including A Dry White Season, Imaginings of Sand, The Rights of Desire and The Other Side of Silence. He has won South Africa's most important literary prize, the CNA Award, three times and has twice been shortlisted for the Booker Prize.

Recenzii

"A soaring, kaleidoscopic account of a slave woman's struggle to protect her humanity. The voice of Philida is wonderfully nuanced and complex—capable of rendering up both the brutality of her experience, and the poetry she manages to wrest from it. A masterful and deeply humane work of art."

—Jennifer Egan, author of A Visit from the Goon Squad

"Powerful. . . . Heartrending. . . . [Brink is] a writer of remarkable compassion and insight. His deeply emotional, complex mix of history and fiction will haunt readers long after the final page is turned."

—BookPage

"Eminent white Afrikaans writer Brink tells a story that is rooted in his own family's ancestry and set in the Cape in the early nineteenth century, before the abolition of slavery. . . . This stirring novel opens up the horror, seldom addressed, of the oppression long before apartheid was the law."

—Booklist

"Words, and the act of recording the truth, lie at the very heart of Brink's novel, from the necessity of Philida's complaint being written down 'very precisely,' to a spill of ink that obliterates the names inscribed in the back of the Brink family bible. In giving a voice to Philida, Brink isn't just rewriting the sins of the fathers—her consciousness is joined by that of Frans, Cornelis, and a freed slave, Petronella, in a cacophony that indicates the shift in the power balance happening in the Cape during this period. . . . Philida's body may not be her own, but her voice certainly is. Her complaint sets in motion a series of events that sends shock waves through the lives of everyone around her: 'One day there must come a time when you got to say for yourself: This and that I shall do, this and that I shall not.'"

—The Daily Beast

"An impossible love story, it is not impossible in the traditional sense of love between mismatched partners, but because it shows how no love is possible between persons fundamentally unequal. Philida's voice is the first voice we hear, and hers is a voice to attend to: idiomatic, lyrical, querulous, searching. . . . The book traces the lacerating trajectory of the sins of parents, parents' scars like open wounds on their children's bodies. There is an astonishing frankness about the facts of life and a visionary lyricism in relation to these cruel facts. The "Acknowledgements" section details the genesis of the novel. In its way, it is as thrilling as the book itself. Extraordinary."

—Kirkus (starred review)

"A moving story of one woman's struggle against hierarchies of race and gender that seek her absolute subjugation, Philida vividly dramatises the courage required to lay claim to the protections of the law, to speak out for one's rights even in the moment in which the law is on the wrong side of history. While this is a familiar story, it is one that must continue to be told, not least by white writers willing, as Brink is, to disinter the histories of complicity buried in their own ancestries."

—The Daily Telegraph (London)

"We are clearly and wholeheartedly on Philida's side—and, indeed, we remain so throughout. But Brink's achievement is to invoke a measure of sympathy for the fading Dutch colonialists as well. There is, it transpires, a profound and substantial relationship between Philida and Frans; and its passing is, arguably, more painful for him than her. . . . There is much, particularly relating to the separation of women slaves from their children, and to the punishments meted out to runaway slaves, that is extremely harrowing. But the light and shade that Brink has skillfully introduced into his augmented family history make for a compelling and memorable novel."

—The Guardian (London)

"In the hands of Mr. Brink, one of South Africa's most famous novelists, the land breathes; it feels alive. . . . Books about slaves, especially the female kind, risk straying into worthiness and sentimentality. Mr. Brink steers well clear. Philida is bawdy and brave. She is pragmatic but sure in her faith that a new day is coming. When that time comes, it will be blue, blue as all other days are blue, and yet, it will be completely different. . . . [Philida] is based on fact. The woman existed. Cornelis was the brother of one of the author's ancestors. Zandvliet is a wine estate, though under another name. They are characters of long ago and far away. But such ghosts forever loom, and Mr. Brink pulls them close."

—The Economist

"As much a biography and autobiography as it is a novel. . . . Brink tells this grand-guignol tale in harrowing style. The book's opening 100 pages or so offer his first successful inhabitation of a genuinely female sensibility. That he inhabits it while also writing in the loose-limbed patois of a 19th-century slave makes the achievement all the more astonishing."

—The Daily Express (London)

"A poignant tale of a slave woman's quest for liberation set in 19th century Cape Town."

—Glass Magazine

"Philida is a very powerful novel, and its graphic accounts . . . [offer] an eloquent indictment of racial and economic oppression."

—The Daily Mail (London)

"[Philida] combines an unflinching examination of the cruelties inflicted on the African people by their Afrikaner masters with an attempt to give voice to the tradition that sustained them. . . . [A] rich and complex novel. . . . A deep love of the South African countryside shines through, woven together with creation myths and earthy folks tales."

—The Times (London)

—Jennifer Egan, author of A Visit from the Goon Squad

"Powerful. . . . Heartrending. . . . [Brink is] a writer of remarkable compassion and insight. His deeply emotional, complex mix of history and fiction will haunt readers long after the final page is turned."

—BookPage

"Eminent white Afrikaans writer Brink tells a story that is rooted in his own family's ancestry and set in the Cape in the early nineteenth century, before the abolition of slavery. . . . This stirring novel opens up the horror, seldom addressed, of the oppression long before apartheid was the law."

—Booklist

"Words, and the act of recording the truth, lie at the very heart of Brink's novel, from the necessity of Philida's complaint being written down 'very precisely,' to a spill of ink that obliterates the names inscribed in the back of the Brink family bible. In giving a voice to Philida, Brink isn't just rewriting the sins of the fathers—her consciousness is joined by that of Frans, Cornelis, and a freed slave, Petronella, in a cacophony that indicates the shift in the power balance happening in the Cape during this period. . . . Philida's body may not be her own, but her voice certainly is. Her complaint sets in motion a series of events that sends shock waves through the lives of everyone around her: 'One day there must come a time when you got to say for yourself: This and that I shall do, this and that I shall not.'"

—The Daily Beast

"An impossible love story, it is not impossible in the traditional sense of love between mismatched partners, but because it shows how no love is possible between persons fundamentally unequal. Philida's voice is the first voice we hear, and hers is a voice to attend to: idiomatic, lyrical, querulous, searching. . . . The book traces the lacerating trajectory of the sins of parents, parents' scars like open wounds on their children's bodies. There is an astonishing frankness about the facts of life and a visionary lyricism in relation to these cruel facts. The "Acknowledgements" section details the genesis of the novel. In its way, it is as thrilling as the book itself. Extraordinary."

—Kirkus (starred review)

"A moving story of one woman's struggle against hierarchies of race and gender that seek her absolute subjugation, Philida vividly dramatises the courage required to lay claim to the protections of the law, to speak out for one's rights even in the moment in which the law is on the wrong side of history. While this is a familiar story, it is one that must continue to be told, not least by white writers willing, as Brink is, to disinter the histories of complicity buried in their own ancestries."

—The Daily Telegraph (London)

"We are clearly and wholeheartedly on Philida's side—and, indeed, we remain so throughout. But Brink's achievement is to invoke a measure of sympathy for the fading Dutch colonialists as well. There is, it transpires, a profound and substantial relationship between Philida and Frans; and its passing is, arguably, more painful for him than her. . . . There is much, particularly relating to the separation of women slaves from their children, and to the punishments meted out to runaway slaves, that is extremely harrowing. But the light and shade that Brink has skillfully introduced into his augmented family history make for a compelling and memorable novel."

—The Guardian (London)

"In the hands of Mr. Brink, one of South Africa's most famous novelists, the land breathes; it feels alive. . . . Books about slaves, especially the female kind, risk straying into worthiness and sentimentality. Mr. Brink steers well clear. Philida is bawdy and brave. She is pragmatic but sure in her faith that a new day is coming. When that time comes, it will be blue, blue as all other days are blue, and yet, it will be completely different. . . . [Philida] is based on fact. The woman existed. Cornelis was the brother of one of the author's ancestors. Zandvliet is a wine estate, though under another name. They are characters of long ago and far away. But such ghosts forever loom, and Mr. Brink pulls them close."

—The Economist

"As much a biography and autobiography as it is a novel. . . . Brink tells this grand-guignol tale in harrowing style. The book's opening 100 pages or so offer his first successful inhabitation of a genuinely female sensibility. That he inhabits it while also writing in the loose-limbed patois of a 19th-century slave makes the achievement all the more astonishing."

—The Daily Express (London)

"A poignant tale of a slave woman's quest for liberation set in 19th century Cape Town."

—Glass Magazine

"Philida is a very powerful novel, and its graphic accounts . . . [offer] an eloquent indictment of racial and economic oppression."

—The Daily Mail (London)

"[Philida] combines an unflinching examination of the cruelties inflicted on the African people by their Afrikaner masters with an attempt to give voice to the tradition that sustained them. . . . [A] rich and complex novel. . . . A deep love of the South African countryside shines through, woven together with creation myths and earthy folks tales."

—The Times (London)

Descriere

Descriere de la o altă ediție sau format:

Francois has reneged on his promise to set her free and his father has ordered him to marry a white woman from a prominent family, selling Philida on to owners in the harsh country in the north. Unwilling to accept this fate, Philida tests the limits of her freedom by setting off on a journey.

Francois has reneged on his promise to set her free and his father has ordered him to marry a white woman from a prominent family, selling Philida on to owners in the harsh country in the north. Unwilling to accept this fate, Philida tests the limits of her freedom by setting off on a journey.