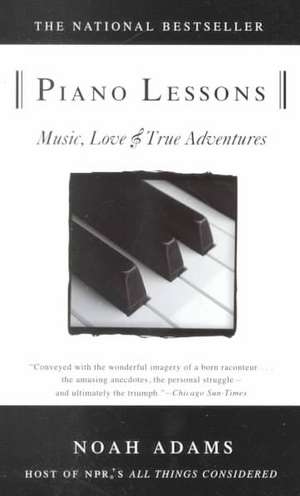

Piano Lessons: Music, Love, and True Adventures

Autor Noah Adamsen Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 1997

Among the up-tempo triumphs and unexpected setbacks, Noah Adams interweaves the rich history and folklore that surround the piano. And along the way, set between the ragtime rhythms and boogie-woogie beats, there are encounters with--and insights from--masters of the keyboard, from Glenn Gould and Leon Fleisher ("I was a bit embarrassed," he writes; "telling Leon Fleisher about my ambitions for piano lessons is like telling Julia Child about plans to make toast in the morning") to Dr. John and Tori Amos.

As a storyteller, Noah Adams has perfect pitch. In the foreground here, like a familiar melody, are the challenges of learning a complex new skill as an adult, when enthusiasm meets the necessary repetition of tedious scales at the end of a twelve-hour workday. Lingering in the background, like a subtle bass line, are the quiet concerns of how we spend our time and how our priorities shift as we proceed through life. For Piano Lessons is really an adventure story filled with obstacles to overcome and grand leaps forward, eccentric geniuses and quiet moments of pre-dawn practice, as Noah Adams travels across country and keyboard, pursuing his dream and keeping the rhythm.

Preț: 114.60 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 172

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.93€ • 22.81$ • 18.11£

21.93€ • 22.81$ • 18.11£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385318211

ISBN-10: 0385318219

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 130 x 210 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: DELTA

ISBN-10: 0385318219

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 130 x 210 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: DELTA

Extras

Play the first note right. The morning--sunrise, eleven degrees, wind dancing across overnight snow--waits for a perfectly struck single note.

"Traumerei," by Robert Schumann, begins with middle C (a year ago this was the only note I could find on the piano). The next note is an F in the right hand joined by an F in the bass; then a cautious chord in both hands and five ascending treble notes lift the song into the air. There's a quick, deep pulse in my throat and a fast breath, and I'm smiling, watching the page, trying to stay up with the melody.

I've come to a quiet place in southern New Hampshire to write about the past year and my involvement with the piano. Often in the early mornings I'll bring a thermos of coffee and my music here to the library, a small stone building at the edge of a field. I'll unlock the heavy front door, turn up the thermostat, take the cover off the piano--it's a Steinway B Model, made in Hamburg, West Germany, in 1962--and play for an hour or so. The ivory-topped keys are cold at first, and so are my hands. I start with exercises, playing in unison an octave apart, up and down the keyboard. Sometimes I notice a tremble, a shaking in the last two fingers of my left hand. In the morning light, though, my hands look young. (The backs of my hands have always seemed old, wrinkled; once at a grade-school Halloween party someone recognized me by my hands, not covered by my ghost costume.)

Then I'll practice "Traumerei." This piece--only two pages, three minutes long--is teaching me piano. There are technical knots to be worked loose, clues to mysteries hiding in the notation. I would be happy to play it several thousand times.

Vladimir Horowitz used to play "Traumerei" as an encore; he said it was a masterpiece. Robert Schumann was only twenty-seven when he wrote the music, and I have the feeling he finished it in a couple of hours, one afternoon. It seems a passionate time in his life; in a letter to a friend he said: "I feel I could almost burst with music--I simply have to compose." Schumann was in love with Clara Wieck, a young piano virtuoso. Her father disapproved and had taken Clara away on a recital tour. "Traumerei" is one of thirteen short pieces in a collection called Kinderszenen (Scenes from Childhood). As Schumann put it, the songs were "reminiscences of a grown-up for grown-ups." (Traumerei translates as "reverie.") And he said in a letter to Clara, "You will enjoy them--though you will have to forget that you are a virtuoso...they're all easy to carry off." Schumann told Clara these pieces were, "peaceful, tender and happy, like our future."

I can see him at his writing desk, and piano, in Leipzig. Excited, dreaming of Clara, his own career as a pianist doomed by a hand injury but by this time knowing that he could be a composer. Twenty-seven years old! Not ten years before, he was a college student, writing home to his mother asking for more money.

I am living like a dog. My hair is yards long and I want to get it cut, but I can't spare a penny. My piano is terribly out of tune but I can't afford to get a tuner. I haven't even got the money for a pistol to shoot myself with....

Your miserable son,

Robert Schumann

He loved drinking and cigars. It seems a historical rumor that he had syphilis. He was probably manicdepressive early as an adult, and later suicidal. He heard hallucinations. "He is in terrible agony," his wife, Clara, wrote in her diary. "Every sound he hears turns to music. Music played on glorious sounding instruments, he says, more beautiful than any music ever heard on earth. It utterly exhausts him."

Robert Schumann died in a mental asylum, at age forty-six. He starved himself to death. Clara did see him, once, as he was dying, but he was kept away from his family for two years. A visitor once peered through an opening in his door and saw him playing a piano, lost apparently in improvisation, but playing music that made no sense. As I sit at this piano in New Hampshire, I have outlived Schumann by six years.

I bought a piece of granite the other day, from a monument company across the road from the town cemetery. I gave the guy twenty dollars and put the "surveyor's post" in the back of my station wagon. Granite is heavy; I don't know why I was surprised. The post is two feet high and about four inches square, with two rough sides and two that have been trimmed smooth. I don't think I'll have to explain this to Neenah, my wife. That the permanence of the granite appeals to me, that the years going by so quickly need marking, with piano lessons and stone. "Oh, that's a good thing to bring back from New Hampshire," she'll say.

I noticed the posts when I was out running, before lunchtime, along the town streets and then out a bit into the country. You'd see them at the corner of a yard by the driveway. The older houses would have large granite posts out front, sometimes chiseled with a street number. And you'd see the odd stub of a post marking a boundary, the stone weathered and chipped by lawn mowers or snow blades. When Robert Schumann died, in 1856, granite buildings in this town had been standing for ten years.

There's not quite enough light on the piano and I have to squint to see the faint marking "a tempo" at the end of the first eight measures of "Traumerei," meaning a return to normal after the slowing of ritard. I've repeated these measures, with some parts a bit softer, taking a teacher's advice: If you don't have something different to say in the repeat, why bother playing it? The tricky middle section waits, a difficult passage in the bass clef, a climb to the treble for another. I remember to relax my shoulders and try to make my hands heavier and pretend these are my favorite parts. It's whistling past the graveyard--and it almost works. I play one chord that's not sounded clearly, I forget to hold an A in the left hand, my foot hits the sustain pedal to slur over a mistake in fingering, but the notes are correct, and there's still a singing quality to the melody.

It's a lovely-sounding piano. A seven-foot grand, shiny mahogany. I have the top all the way up, as you would for a concert. It is my dream, when I touch the keys, to release the notes. It is music waiting there, and for me it is as real as the blown snow against the windows, and the evening's quarter moon rising through a cold fog, or the stories told of wolves that lived on nearby Mount Monadnock, sheltering in the red oak trees. Robert Frost wrote about valleys and mountains like these and once of a farmer whose land was so high up that his neighbors could watch the light of his lantern as he went about his chores.

I can feel my shoulders tightening again as I get close to the end of"Traumerei." I try to sway a bit on the piano bench, and I sing out loud with the phrases. The opening theme returns, starting with middle C. Then up to a solid, proud seven-note chord and (ritardando) a stately, quiet finish. There is a fermata over the final chord: a black dot with a half circle on top. A "bird's eye" musicians call it. The symbol means, "Hold it as long as you want to, you've earned it." And there's a pedal marking at the bottom; the pedal goes down as you play the chord so all the other Fs and As on the keyboard sound in sympathetic resonance.

I gently release the pedal and the final, whispering tones are dampened and lost in the warming rush of air from the furnace. There's a small puddle of water from my boots on the flagstone floor. The sunlight has now reached the trees at the edge of the field.

On the shelves around the piano are bound volumes of sheet music, Strauss and Wagner, Mozart. Schumann's works are here, in several volumes. I can play one of his songs, imperfectly (I've surely played "Traumerei" more times than he did), and it's really the only piece of music that I've learned. But it was an unanticipated, almost reckless year. I was at first surprised and delighted by the piano, then daunted, then discouraged. By the fall I had almost given up. By October's end, though, I was learning. In November and December, as now, I wanted to spend all my time practicing.

I'll take the granite post back home to Washington and, when the weather warms, dig a hole for it at the edge of the garden, You could set your coffee cup on top of the post, or a trowel.

I'll play the piano for my wife, early in the morning, and tell her about my adventures.

N. D. A. (February 1995) The MacDowell Colony

Peterborough, New Hampshire

"Traumerei," by Robert Schumann, begins with middle C (a year ago this was the only note I could find on the piano). The next note is an F in the right hand joined by an F in the bass; then a cautious chord in both hands and five ascending treble notes lift the song into the air. There's a quick, deep pulse in my throat and a fast breath, and I'm smiling, watching the page, trying to stay up with the melody.

I've come to a quiet place in southern New Hampshire to write about the past year and my involvement with the piano. Often in the early mornings I'll bring a thermos of coffee and my music here to the library, a small stone building at the edge of a field. I'll unlock the heavy front door, turn up the thermostat, take the cover off the piano--it's a Steinway B Model, made in Hamburg, West Germany, in 1962--and play for an hour or so. The ivory-topped keys are cold at first, and so are my hands. I start with exercises, playing in unison an octave apart, up and down the keyboard. Sometimes I notice a tremble, a shaking in the last two fingers of my left hand. In the morning light, though, my hands look young. (The backs of my hands have always seemed old, wrinkled; once at a grade-school Halloween party someone recognized me by my hands, not covered by my ghost costume.)

Then I'll practice "Traumerei." This piece--only two pages, three minutes long--is teaching me piano. There are technical knots to be worked loose, clues to mysteries hiding in the notation. I would be happy to play it several thousand times.

Vladimir Horowitz used to play "Traumerei" as an encore; he said it was a masterpiece. Robert Schumann was only twenty-seven when he wrote the music, and I have the feeling he finished it in a couple of hours, one afternoon. It seems a passionate time in his life; in a letter to a friend he said: "I feel I could almost burst with music--I simply have to compose." Schumann was in love with Clara Wieck, a young piano virtuoso. Her father disapproved and had taken Clara away on a recital tour. "Traumerei" is one of thirteen short pieces in a collection called Kinderszenen (Scenes from Childhood). As Schumann put it, the songs were "reminiscences of a grown-up for grown-ups." (Traumerei translates as "reverie.") And he said in a letter to Clara, "You will enjoy them--though you will have to forget that you are a virtuoso...they're all easy to carry off." Schumann told Clara these pieces were, "peaceful, tender and happy, like our future."

I can see him at his writing desk, and piano, in Leipzig. Excited, dreaming of Clara, his own career as a pianist doomed by a hand injury but by this time knowing that he could be a composer. Twenty-seven years old! Not ten years before, he was a college student, writing home to his mother asking for more money.

I am living like a dog. My hair is yards long and I want to get it cut, but I can't spare a penny. My piano is terribly out of tune but I can't afford to get a tuner. I haven't even got the money for a pistol to shoot myself with....

Your miserable son,

Robert Schumann

He loved drinking and cigars. It seems a historical rumor that he had syphilis. He was probably manicdepressive early as an adult, and later suicidal. He heard hallucinations. "He is in terrible agony," his wife, Clara, wrote in her diary. "Every sound he hears turns to music. Music played on glorious sounding instruments, he says, more beautiful than any music ever heard on earth. It utterly exhausts him."

Robert Schumann died in a mental asylum, at age forty-six. He starved himself to death. Clara did see him, once, as he was dying, but he was kept away from his family for two years. A visitor once peered through an opening in his door and saw him playing a piano, lost apparently in improvisation, but playing music that made no sense. As I sit at this piano in New Hampshire, I have outlived Schumann by six years.

I bought a piece of granite the other day, from a monument company across the road from the town cemetery. I gave the guy twenty dollars and put the "surveyor's post" in the back of my station wagon. Granite is heavy; I don't know why I was surprised. The post is two feet high and about four inches square, with two rough sides and two that have been trimmed smooth. I don't think I'll have to explain this to Neenah, my wife. That the permanence of the granite appeals to me, that the years going by so quickly need marking, with piano lessons and stone. "Oh, that's a good thing to bring back from New Hampshire," she'll say.

I noticed the posts when I was out running, before lunchtime, along the town streets and then out a bit into the country. You'd see them at the corner of a yard by the driveway. The older houses would have large granite posts out front, sometimes chiseled with a street number. And you'd see the odd stub of a post marking a boundary, the stone weathered and chipped by lawn mowers or snow blades. When Robert Schumann died, in 1856, granite buildings in this town had been standing for ten years.

There's not quite enough light on the piano and I have to squint to see the faint marking "a tempo" at the end of the first eight measures of "Traumerei," meaning a return to normal after the slowing of ritard. I've repeated these measures, with some parts a bit softer, taking a teacher's advice: If you don't have something different to say in the repeat, why bother playing it? The tricky middle section waits, a difficult passage in the bass clef, a climb to the treble for another. I remember to relax my shoulders and try to make my hands heavier and pretend these are my favorite parts. It's whistling past the graveyard--and it almost works. I play one chord that's not sounded clearly, I forget to hold an A in the left hand, my foot hits the sustain pedal to slur over a mistake in fingering, but the notes are correct, and there's still a singing quality to the melody.

It's a lovely-sounding piano. A seven-foot grand, shiny mahogany. I have the top all the way up, as you would for a concert. It is my dream, when I touch the keys, to release the notes. It is music waiting there, and for me it is as real as the blown snow against the windows, and the evening's quarter moon rising through a cold fog, or the stories told of wolves that lived on nearby Mount Monadnock, sheltering in the red oak trees. Robert Frost wrote about valleys and mountains like these and once of a farmer whose land was so high up that his neighbors could watch the light of his lantern as he went about his chores.

I can feel my shoulders tightening again as I get close to the end of"Traumerei." I try to sway a bit on the piano bench, and I sing out loud with the phrases. The opening theme returns, starting with middle C. Then up to a solid, proud seven-note chord and (ritardando) a stately, quiet finish. There is a fermata over the final chord: a black dot with a half circle on top. A "bird's eye" musicians call it. The symbol means, "Hold it as long as you want to, you've earned it." And there's a pedal marking at the bottom; the pedal goes down as you play the chord so all the other Fs and As on the keyboard sound in sympathetic resonance.

I gently release the pedal and the final, whispering tones are dampened and lost in the warming rush of air from the furnace. There's a small puddle of water from my boots on the flagstone floor. The sunlight has now reached the trees at the edge of the field.

On the shelves around the piano are bound volumes of sheet music, Strauss and Wagner, Mozart. Schumann's works are here, in several volumes. I can play one of his songs, imperfectly (I've surely played "Traumerei" more times than he did), and it's really the only piece of music that I've learned. But it was an unanticipated, almost reckless year. I was at first surprised and delighted by the piano, then daunted, then discouraged. By the fall I had almost given up. By October's end, though, I was learning. In November and December, as now, I wanted to spend all my time practicing.

I'll take the granite post back home to Washington and, when the weather warms, dig a hole for it at the edge of the garden, You could set your coffee cup on top of the post, or a trowel.

I'll play the piano for my wife, early in the morning, and tell her about my adventures.

N. D. A. (February 1995) The MacDowell Colony

Peterborough, New Hampshire

Recenzii

"Piano Lessons provides that rare and special pleasure of finding both entertainment and information in the most unexpected places."

--Bailey White, author of Sleeping at the Starlite Motel

--Bailey White, author of Sleeping at the Starlite Motel

Descriere

With all of Noah Adams' accomplishments, the award-winning host of NPR's "All Things Considered" had one challenge yet to tackle: a lifelong dream to play the piano. "Piano Lessons" presents the 12-month chronicle of his long road to success--complete with folklore and history about the piano, plus insights from master pianists such as Vladimir Horowitz and Harry Connick, Jr.

Notă biografică

Noah Adams is a contributing correspondent for NPR News and the author of The Flyers: in Search of Wilbur and Orville Wright. In his current position, he works with NPR's National Desk to cover stories on the working poor across America. He lives with his wife, Neenah Ellis, a freelance journalist, in Yellow Springs, Ohio.