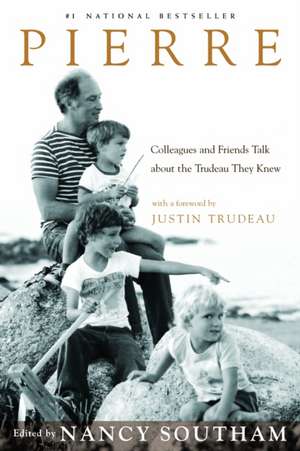

Pierre: Colleagues and Friends Talk about the Trudeau They Knew

Justin Trudeau Editat de Nancy Southamen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2006

When Pierre Elliott Trudeau died in 2000, the outpouring of emotion was extraordinary. Thousands of people across Canada — and all over the world — mourned the loss of one of our greatest prime ministers, a man who touched the hearts and challenged the minds of a nation. In this book, Trudeau’s close friend Nancy Southam has gathered more than 140 reminiscences and anecdotal narratives from journalists, former world leaders, politicians who battled and debated him, his sons’ friends, RCMP bodyguards, girlfriends, canoeing buddies, and household staff. Among the contributors are luminaries as diverse as Conrad Black, Jean Chrétien, Leonard Cohen, John Kenneth Galbraith, Ivan Head, Jacques Hébert, Karen Kain, Margot Kidder, Harrison McCain, Toni Onley, Gordon Pinsent, Christopher Plummer, Roy Romanow, Ed Schreyer, and Barbra Streisand. With the blessing of his sons, Justin and Sacha, Southam has put together a remarkably transparent account of a deeply private person that is funny, honest, affectionate, and illuminating.

Preț: 115.89 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 174

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.18€ • 23.20$ • 18.42£

22.18€ • 23.20$ • 18.42£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780771081682

ISBN-10: 0771081685

Pagini: 388

Ilustrații: B&W PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 152 x 226 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.45 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

ISBN-10: 0771081685

Pagini: 388

Ilustrații: B&W PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 152 x 226 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.45 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

Recenzii

“[Southam’s] observations on Trudeau . . . are intimate, arresting, funny and deeply affecting. They and so many others here reveal a humanity and vulnerability which only those closest to him could see behind the cerebral, ascetic, stoic public man.”

— Andrew Cohen, Globe and Mail

“Lavishly illustrated and easy to peruse, Pierre is grist for the mill for readers who revere Canada’s most controversial, yet celebrated politician.”

— London Free Press

“Arrogant, shy, charming, rude, kind, thoughtless — all the contradictory traits of Canada’s best-known 20th century prime minister, Pierre Trudeau, show up in this collection of anecdotes by friends and colleagues. . . . Love him or hate him, Trudeau was a one-off, and Southam’s book shows him in all his vaunted complexity.”

— Toronto Sun

— Andrew Cohen, Globe and Mail

“Lavishly illustrated and easy to peruse, Pierre is grist for the mill for readers who revere Canada’s most controversial, yet celebrated politician.”

— London Free Press

“Arrogant, shy, charming, rude, kind, thoughtless — all the contradictory traits of Canada’s best-known 20th century prime minister, Pierre Trudeau, show up in this collection of anecdotes by friends and colleagues. . . . Love him or hate him, Trudeau was a one-off, and Southam’s book shows him in all his vaunted complexity.”

— Toronto Sun

Notă biografică

Journalist and author Nancy Southam is the editor of Remembering Richard: An Informal Portrait of Richard Hatfield. Southam was a neighbour, travelling companion, and close friend of Pierre Elliott Trudeau in Montreal.

Extras

From Chapter One: Faith

ALLAN J. MACEACHEN

MP, 1953–57 and 1962–80; and Senator, 1984–96

The only written reference made by Mr. Trudeau about his religious views that I have been able to find was a short interview he gave to the United Church Observer. In it he was pressed to speak about whether he was “a devout Catholic.” After initial parrying and dialectical probing, he gave more than the interviewer asked, by declaring, “I am a believer.” Then he virtually recited, for the benefit of the United Church, the substance of the Apostle’s Creed.

Another reference to religion in his public utterances was not as devotional. It was a reference that – at one particular moment – I wished he had omitted. In the 1972 general election campaign, I was visiting door-to-door in the district of Little Narrows, my Cape Breton constituency. I was accompanied by the warden of Victoria County, the late Kenneth Matheson, who was also the councillor for the Little Narrows municipal district. Both the warden and the district were staunchly Presbyterian. They took religious matters seriously. Religion was not a subject for flippant treatment.

Together, we entered the home of a church member as she was about to leave for a church meeting. She was dressed for the occasion and carried a formidable black handbag. The innate sense of hospitality characteristic of Highland stock imposed in her mind a greater duty than punctual attendance at the scheduled church meeting. She invited us to sit down.

“We have always been Liberals,” she said. “Not that we think we are better than the others. It just suits us to be Liberal.”

That was a good beginning, except for the “better” reference, which – in the stress of an election campaign – I thought could well be omitted. Then our hostess got down to business.

“Now,” she said, as she opened her purse and handed me a newspaper clipping, “your prime minister is causing me difficulties.”

I read the newspaper account with increasing dismay. Now, some background is required. In the 1968 election campaign, Mr. Trudeau had highlighted the Just Society. The electorate could be forgiven for concluding that the Just Society would be ushered in forthwith, following Mr. Trudeau’s election victory. This expectation had obviously been on the mind of an elector in southern Ontario, during this 1972 campaign, when heckling Mr. Trudeau.

“Mr. Trudeau,” he had asked, “where is the Just Society you promised?”

Here is what Mr. Trudeau was quoted in the clipping as saying: “Ask Jesus Christ. He promised it first.”

Finally, my hostess interrupted my longer-than-required gaze at the newspaper clipping that detailed this exchange.

“I regard that as blasphemy, Mr. MacEachen,” she said. I had to say something other than my immediate thoughts, which were clearly in her corner, and if expressed would likely have revealed my dismay at the irreverence of the pm’s comments. In addition, my concern went beyond the irreverence of the remark. The timing was awful. The electoral consequences of such flippancy might be felt in my constituency, and far and wide in Canada.

I did try, however, to reduce the anxiety by questioning the accuracy of the report. One could not always rely on such reports, I offered. It was surprising to me that such a remark would be made by the prime minister, I suggested. No doubt my effort was feeble and unconvincing. Knowing my leader as I did, deep down I feared the rapid-fire retort could indeed have happened as reported.

Years later, after we had left office, I recounted the incident in Mr. Trudeau’s presence, at the launch of a book on the Trudeau legacy. He did not challenge my account. Instead Mr. Trudeau sat quietly, with a suppressed smile on his face, possibly taking some pleasure in the audacity of his remarks.

Postscript: we lost our majority in that election.

HASSAN YASSIN

Head of the Saudi Arabian Information Office in Washington, D.C., 1970—80

I knew former prime minister Pierre Trudeau since 1976. While he was prime minister, I visited Ottawa many times, and he always received my friends and me very graciously. Mr. Trudeau was my guest many times in Washington, while I was head of the Saudi information office there, and we also enjoyed a number of skiing trips together in Colorado.

Pierre Trudeau’s unique character, his profound understanding of others, and his deep humanity are to me best described by an occasion that has left a lasting impression on me. While he was prime minister, he visited me one summer in Marbella, at my residence in Porto Banus. He recounted to me his time as a student at the Sorbonne and a motorcycle trip he took, in 1947, around Europe and North Africa. On that trip, he had come across the village of Rhonda in the mountains of Marbella where – during the Arab occupation of Spain – a magnificent mosque had been erected, which was later converted into a church.

He asked me if I would like to visit this village with him. I agreed, and we requested special permission to visit the church with the priest that afternoon. The site and the converted mosque were as beautiful as Mr. Trudeau had promised. Upon seeing Quranic inscriptions on the walls, I innocently asked both the prime minister and the priest whether it was possible for me to pray as a Muslim in the church.

Mr. Trudeau immediately acquiesced to the idea. He then asked if I could lead a prayer as an imam, while he and the priest bowed in Muslim tradition. Mr. Trudeau consulted with the priest and, in this magnificent moment, the prime minister in his way contributed to uniting the two great religions of Christianity and Islam in peace and understanding. His desire to understand other people’s faith traditions – to live by consensus rather than by confrontation – was his greatest strength.

B.W. POWE

Writer, teacher, author

1989: we lunched at a Chinese restaurant, not far from Trudeau’s new office on RenéLévesque Boulevard.

My intentions for that meeting: to ask him to attend the Trudeau Era conference I was directing at York University in Toronto. He refused (politely), but he did ask about who was scheduled to speak, and on what subjects. I singled out a talk to be given by Michael Higgins, Vice-President and Academic Dean at St. Jerome’s, at the University of Waterloo, on the influence of faith on Trudeau’s thinking.

“He will be talking about the importance of religion, of your Catholic background, on your thought and approaches to political ideas,” I said.

Trudeau leaned back, looked off, and said, vehemently:

“At last.”

ALLAN J. MACEACHEN

MP, 1953–57 and 1962–80; and Senator, 1984–96

The only written reference made by Mr. Trudeau about his religious views that I have been able to find was a short interview he gave to the United Church Observer. In it he was pressed to speak about whether he was “a devout Catholic.” After initial parrying and dialectical probing, he gave more than the interviewer asked, by declaring, “I am a believer.” Then he virtually recited, for the benefit of the United Church, the substance of the Apostle’s Creed.

Another reference to religion in his public utterances was not as devotional. It was a reference that – at one particular moment – I wished he had omitted. In the 1972 general election campaign, I was visiting door-to-door in the district of Little Narrows, my Cape Breton constituency. I was accompanied by the warden of Victoria County, the late Kenneth Matheson, who was also the councillor for the Little Narrows municipal district. Both the warden and the district were staunchly Presbyterian. They took religious matters seriously. Religion was not a subject for flippant treatment.

Together, we entered the home of a church member as she was about to leave for a church meeting. She was dressed for the occasion and carried a formidable black handbag. The innate sense of hospitality characteristic of Highland stock imposed in her mind a greater duty than punctual attendance at the scheduled church meeting. She invited us to sit down.

“We have always been Liberals,” she said. “Not that we think we are better than the others. It just suits us to be Liberal.”

That was a good beginning, except for the “better” reference, which – in the stress of an election campaign – I thought could well be omitted. Then our hostess got down to business.

“Now,” she said, as she opened her purse and handed me a newspaper clipping, “your prime minister is causing me difficulties.”

I read the newspaper account with increasing dismay. Now, some background is required. In the 1968 election campaign, Mr. Trudeau had highlighted the Just Society. The electorate could be forgiven for concluding that the Just Society would be ushered in forthwith, following Mr. Trudeau’s election victory. This expectation had obviously been on the mind of an elector in southern Ontario, during this 1972 campaign, when heckling Mr. Trudeau.

“Mr. Trudeau,” he had asked, “where is the Just Society you promised?”

Here is what Mr. Trudeau was quoted in the clipping as saying: “Ask Jesus Christ. He promised it first.”

Finally, my hostess interrupted my longer-than-required gaze at the newspaper clipping that detailed this exchange.

“I regard that as blasphemy, Mr. MacEachen,” she said. I had to say something other than my immediate thoughts, which were clearly in her corner, and if expressed would likely have revealed my dismay at the irreverence of the pm’s comments. In addition, my concern went beyond the irreverence of the remark. The timing was awful. The electoral consequences of such flippancy might be felt in my constituency, and far and wide in Canada.

I did try, however, to reduce the anxiety by questioning the accuracy of the report. One could not always rely on such reports, I offered. It was surprising to me that such a remark would be made by the prime minister, I suggested. No doubt my effort was feeble and unconvincing. Knowing my leader as I did, deep down I feared the rapid-fire retort could indeed have happened as reported.

Years later, after we had left office, I recounted the incident in Mr. Trudeau’s presence, at the launch of a book on the Trudeau legacy. He did not challenge my account. Instead Mr. Trudeau sat quietly, with a suppressed smile on his face, possibly taking some pleasure in the audacity of his remarks.

Postscript: we lost our majority in that election.

HASSAN YASSIN

Head of the Saudi Arabian Information Office in Washington, D.C., 1970—80

I knew former prime minister Pierre Trudeau since 1976. While he was prime minister, I visited Ottawa many times, and he always received my friends and me very graciously. Mr. Trudeau was my guest many times in Washington, while I was head of the Saudi information office there, and we also enjoyed a number of skiing trips together in Colorado.

Pierre Trudeau’s unique character, his profound understanding of others, and his deep humanity are to me best described by an occasion that has left a lasting impression on me. While he was prime minister, he visited me one summer in Marbella, at my residence in Porto Banus. He recounted to me his time as a student at the Sorbonne and a motorcycle trip he took, in 1947, around Europe and North Africa. On that trip, he had come across the village of Rhonda in the mountains of Marbella where – during the Arab occupation of Spain – a magnificent mosque had been erected, which was later converted into a church.

He asked me if I would like to visit this village with him. I agreed, and we requested special permission to visit the church with the priest that afternoon. The site and the converted mosque were as beautiful as Mr. Trudeau had promised. Upon seeing Quranic inscriptions on the walls, I innocently asked both the prime minister and the priest whether it was possible for me to pray as a Muslim in the church.

Mr. Trudeau immediately acquiesced to the idea. He then asked if I could lead a prayer as an imam, while he and the priest bowed in Muslim tradition. Mr. Trudeau consulted with the priest and, in this magnificent moment, the prime minister in his way contributed to uniting the two great religions of Christianity and Islam in peace and understanding. His desire to understand other people’s faith traditions – to live by consensus rather than by confrontation – was his greatest strength.

B.W. POWE

Writer, teacher, author

1989: we lunched at a Chinese restaurant, not far from Trudeau’s new office on RenéLévesque Boulevard.

My intentions for that meeting: to ask him to attend the Trudeau Era conference I was directing at York University in Toronto. He refused (politely), but he did ask about who was scheduled to speak, and on what subjects. I singled out a talk to be given by Michael Higgins, Vice-President and Academic Dean at St. Jerome’s, at the University of Waterloo, on the influence of faith on Trudeau’s thinking.

“He will be talking about the importance of religion, of your Catholic background, on your thought and approaches to political ideas,” I said.

Trudeau leaned back, looked off, and said, vehemently:

“At last.”