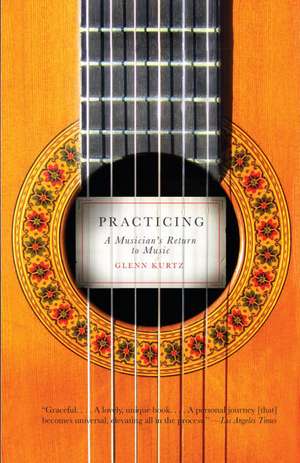

Practicing: A Musician's Return to Music

Autor Glenn Kurtzen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2008

But not forever: Returning to the guitar, Kurtz weaves into the narrative the rich experience of a single practice session. Practicing takes us on a revelatory, inspiring journey: a love affair with music.

Preț: 128.58 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 193

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.60€ • 25.74$ • 20.44£

24.60€ • 25.74$ • 20.44£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 13-27 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307278753

ISBN-10: 0307278751

Pagini: 239

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0307278751

Pagini: 239

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Glenn Kurtz holds a Ph.D. in comparative literature from Stanford University and has taught at San Francisco State University, California College of the Arts, and Stanford. He divides his time between San Francisco and New York.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Sitting Down

I am sitting down to practice. I open the case and take out my instrument, a classical guitar made from the door of a Spanish church. I strike a tuning fork against my knee and hold it to my ear, then gently pluck an open string. During the night the guitar has drifted out of tune. It tries to pull the tuning fork with it, and I feel the friction of discordant vibrations against my eardrum. I turn the tuning peg slightly, bracing it between my thumb and index finger, until the two sounds converge. Another barely perceptible adjustment, and the vibrations melt together, becoming one. From string to string, I repeat the process, resolving discord with minute twists of my wrist. Then I check high notes against low, middle against outer. Finally I play a chord, sounding all six strings together. Each note rubs the others just right, and the instrument shivers with delight. The feeling is unmistakable, intoxicating. When a guitar is perfectly in tune, its strings, its whole body will resonate in sympathetic vibration, the true concord of well-tuned sounds. It is an ancient, hopeful metaphor, an instrument in tune, speaking of pleasure on earth and order in the cosmos, the fragility of beauty, and the quiver in our longing for love.

With a metal emery board, then with very fine sandpaper, I file the nails on my right hand. Even the tiniest ridges can catch on a string and make its tone raspy. In 1799 Portuguese guitarist Antonio Abreu suggested trimming the nails with scissors, then smoothing them on a sharpening stone to remove “rough edges that might impede the execution of flourishes and lively scales.” Some guitarists disagree heatedly with this advice, preferring to play with the fingertips alone. For support, they quote Miguel Fuenllana, who in 1554 stated that “to strike with the nails is imperfection. Only the finger, the living thing, can communicate the intention of the spirit.” But to my ear, the spirit of music speaks with many voices, and a combination of fingernail and flesh sounds best. I run my thumb over my fingertips. They are as smooth as crystal.

I shift the guitar into its proper position, settle its weight, and adjust my body to the familiar contours. And then I look around me. My chair is by a window in the living room; my footstool and music stand are in front of me. The window shade is partly drawn so that the San Francisco sunlight falls at my feet but not on my instrument, which would warp in the heat. Outside, people with briefcases and regular jobs are walking down the hill to work. Students are arriving at the school across the street. I listen to their voices and footsteps. Then I take a deep breath, letting them go. I draw myself in. I’m alone in the apartment, and my work is here. I begin.

At first I just play chords. The sounds feel bulky, as do my hands. I concentrate on the simplest task, to play all the notes at precisely the same moment, with one thought, one motion. It takes a few minutes; sometimes, on bad days, it takes all morning. I take my time. But I cannot proceed without this unity of thought, motion, and sound.

Slowly the effort wakes my fingers. Slowly they warm. As the muscles loosen, I break the chords into arpeggios: the same notes, but now spread out, each with its own place, its own demands. Arpeggios make the fingers of both hands work together in different combinations. I play deliberately, building a triangle of sound—fingertip, ear, fingertip—until my hands become aware of each other.

My attention warms and sharpens, and I shape the notes more carefully. I remember now that music is vibration, a disturbance in the air. I remember that music is a kind of breathing, an exchange of energy and excitement. I remember that music is physical, not just in the production of sounds, in the instrumentalist’s technique, but as an experience. Making music changes my body, eliciting shivers, sobs, or the desire to dance. I become aware of myself, of these sensations that lie dormant until music brings them out. And in an instant the pleasure, the effort, the ambition and intensity of playing grip me and shake me awake. I feel as if I’ve been wandering aimlessly until now, as if all the time I’m not practicing, I’m a sleepwalker.

I calm myself and concentrate. Give the sounds time, let the instrument vibrate. I have to hear the sounds I want before I make them, and I have to let the sounds be what they are. Then I have to hear the difference between what I have in mind and what comes from the strings.

It’s easy to get carried away. The grandeur, the depth and beauty of music are always present in the practice room. Holding the guitar, I feel music’s power at my fingertips, as if I might pluck a string and change the world. For centuries people believed that music was the force that moved the planets. Looking into the night sky, astronomers saw the harmony of heaven, and philosophers heard the music of the spheres. Musicians were prophets then, and according to Cicero the most talented might gain entry to heaven while still alive simply “by imitating this harmony on stringed instruments.” Every artist must sometimes believe that art is the doorway to the divine. Perhaps it is. But it’s dangerous for a musician to philosophize instead of practicing. The grandeur of music, to be heard, must be played. When I hold the guitar, I may aspire to play perfect harmonies. But first I have to play well.

I bring myself back to the work at hand. I listen to the strings, while testing fine gradations in the angle, speed, and strength of my touch. I vary the dynamics and articulation, vary the intensity and color of the notes. If I am to play well, I must gather the guitar’s many voices, let each one sing out. After a few more minutes of arpeggios, my fingers grow warm and capable. The notes are clear and distinct, and I play the simple chords again, very softly at first, then louder and more urgently. Again, softly, then filling, expanding, releasing. Once more, until gradually the sounds from the instrument near what I hear in my head.

Listening, drawing sound, motion, and thought together, I find my concentration. My imagination opens and reaches out. And in that reaching I begin to recognize myself. My hands feel like my hands and not the mitts I usually walk around with. I recognize my instrument’s tone; this is how I sound, for now. I recognize my body; I feel alert and able. I feel like a musician again, a classical guitarist. I feel ready to work, ready to play.

“For the past eighty years I have started each day in the same manner,” wrote the cellist Pablo Casals in his memoir, Joys and Sorrows. “I go to the piano, and I play two preludes and fugues of Bach. It fills me with awareness of the wonder of life, with a feeling of the incredible marvel of being a human being.”

Try to describe your experience of music, and you’ll quickly reach the limits of words. Music carries us away, and we grope for the grandest terms in our vocabulary just to hint at the marvel of the flight, the incredible marvel, the wonder. “Each day,” Casals continues, “it is something new, fantastic, and unbelievable.” I imagine him leaning forward in excitement, a round-faced bald man in his eighties, gesturing with his hands, then meeting my eyes to see if I’ve understood. Fantastic and unbelievable. The words say little. But yes, I think I understand.

I’m sitting down to practice, and like Casals, I’m grasping for words to equal my experience. Alone in the practice room, I hold my instrument silently. Every day it is the same task, yet something new. I delve down, seeking what hides waiting in the notes, what lies dormant in myself that music brings to life. I close my eyes and listen for the unheard melody in what I’ve played a hundred times before, the unsuspected openings.

What are the tones, the terms, that unlock music’s power, the pleasure and profundity we experience in listening? I begin to play, leaning forward excitedly and grasping for the right notes, my whole body alive with aspiration. Sounds ring out, ripening for a moment in the air, then dying away. I play the same notes again, reaching for more of the sweetness, the bittersweetness they contain and express. And again the sounds ring out, float across the room, and fall still. Each day, with every note, practicing is the same task, this essential human gesture—reaching out for an ideal, for the grandeur of what you desire, and feeling it slip through your fingers.

Practicing music—practicing anything we really love—we are always at the limit of words, striving for something just beyond our ability to express. Sometimes, when we speak of this work, therefore, we make this the goal, emphasizing the pleasure of reaching out. Practicing, writes Yehudi Menuhin, is “the search for ever greater joy in movement and expression. This is what practice is really about.” But frequently we experience a darker, harsher mood, aware in each moment of what slips away unattained. Then pleasure seems like nourishment for the journey, but it is not what carries us forward. When musicians speak of this experience, they often stress the labor, warning how difficult a path it is, how lonesome and demanding. The great Spanish guitarist Andrés Segovia cautioned that “it is impossible to feign mastery of an instrument, however skillful the impostor may be.” But to attain mastery, if it is possible at all, requires “the stern discipline of lifelong practice.” For the listener, Segovia says, music might seem effortless or divine. But for the musician it is the product of supreme effort and devotion, the feast at the end of the season.

Like every practicing musician, I know both the joy and the hard labor of practice. To hear these sounds emerging from my instrument! And to hear them more clearly, more beautifully in my head than my fingers can ever seem to grasp. Together this pleasure in music and the discipline of practice engage in an endless tussle, a kind of romance. The sense of joy justifies the labor; the labor, I hope, leads to joy. This, at least, is the bargain I quietly make with myself each morning as I sit down. If I just do my work, then pleasure, mastery will follow. Even the greatest artists must make the same bargain. “I was obliged to work hard,” Johann Sebastian Bach is supposed to have said. And I want so much to believe him when he promises that “whoever is equally industrious will succeed just as well.”

Yet as I wrap my arms around the guitar to play, I also hear another voice whispering in my ears. “Whatever efforts we may make,” warned Jean-Jacques Rousseau in his 1767 Dictionary of Music, “we must still be born to the art, otherwise our works can never mount above the insipid.” In every musician’s mind lurks the fear that practicing is merely busywork, that you are either born to your instrument or you are an impostor. Trusting Bach and Segovia, I cling to the belief that my effort will, over time, yield mastery. But this faith sometimes seems naïve, merely a wish. “The capacity for melody is a gift,” asserted Igor Stravinsky. “This means that it is not within our power to develop it by study.” Practice all you want, Rousseau and Stravinsky say, but you will never become a musician if you don’t start out one. Perhaps practice will carry me only so far. Perhaps, as Oscar Wilde put it, “only mediocrities develop.”

I shake out my hands. Outside on the street, the morning commute is over. The workday has begun; school is in session. Only tourists pass by my window now, lumbering up the hill in search of Lombard Street, “the crookedest street in the world.” I walk down this tourist attraction all the time, a pretty, twisting street festooned with flowers. Now, from my chair, I watch a family cluster around a map, Mom, Dad, and two red-haired teenage boys, each pointing in a different direction. They’re just a block from their destination, but they don’t know it, lost within sight of their goal. I feel that way every day.

Practicing is striving; practicing is a romance. But practicing is also a risk, a test of character, a threat of deeply personal failure. I warm up my hands and awaken my ears and imagination, developing skill to equal my experience. I listen and concentrate in an effort to make myself better. Yet every day I collide with my limits, the constraints of my hands, my instrument, and my imagination. Each morning when I sit down, I’m bewildered by a cacophony of voices, encouraging and dismissive, joyous and harsh, each one a little tyrant, each one insisting on its own direction. And I struggle to harmonize them, to find my way between them, uncertain whether this work is worth it or a waste of my time.

Everything I need to make music is here, my hands, my instrument, my imagination, and these notes. For most of their lives Segovia, Casals, Bach, and Stravinsky were also just men sitting alone in a room with these same raw materials, looking out the window at people on the street. Like me, they must at times have wondered how to grasp the immensity of music’s promise in a few simple notes, how to hold fast to their devotion against a cutting doubt that would kill it.

From the Hardcover edition.

I am sitting down to practice. I open the case and take out my instrument, a classical guitar made from the door of a Spanish church. I strike a tuning fork against my knee and hold it to my ear, then gently pluck an open string. During the night the guitar has drifted out of tune. It tries to pull the tuning fork with it, and I feel the friction of discordant vibrations against my eardrum. I turn the tuning peg slightly, bracing it between my thumb and index finger, until the two sounds converge. Another barely perceptible adjustment, and the vibrations melt together, becoming one. From string to string, I repeat the process, resolving discord with minute twists of my wrist. Then I check high notes against low, middle against outer. Finally I play a chord, sounding all six strings together. Each note rubs the others just right, and the instrument shivers with delight. The feeling is unmistakable, intoxicating. When a guitar is perfectly in tune, its strings, its whole body will resonate in sympathetic vibration, the true concord of well-tuned sounds. It is an ancient, hopeful metaphor, an instrument in tune, speaking of pleasure on earth and order in the cosmos, the fragility of beauty, and the quiver in our longing for love.

With a metal emery board, then with very fine sandpaper, I file the nails on my right hand. Even the tiniest ridges can catch on a string and make its tone raspy. In 1799 Portuguese guitarist Antonio Abreu suggested trimming the nails with scissors, then smoothing them on a sharpening stone to remove “rough edges that might impede the execution of flourishes and lively scales.” Some guitarists disagree heatedly with this advice, preferring to play with the fingertips alone. For support, they quote Miguel Fuenllana, who in 1554 stated that “to strike with the nails is imperfection. Only the finger, the living thing, can communicate the intention of the spirit.” But to my ear, the spirit of music speaks with many voices, and a combination of fingernail and flesh sounds best. I run my thumb over my fingertips. They are as smooth as crystal.

I shift the guitar into its proper position, settle its weight, and adjust my body to the familiar contours. And then I look around me. My chair is by a window in the living room; my footstool and music stand are in front of me. The window shade is partly drawn so that the San Francisco sunlight falls at my feet but not on my instrument, which would warp in the heat. Outside, people with briefcases and regular jobs are walking down the hill to work. Students are arriving at the school across the street. I listen to their voices and footsteps. Then I take a deep breath, letting them go. I draw myself in. I’m alone in the apartment, and my work is here. I begin.

At first I just play chords. The sounds feel bulky, as do my hands. I concentrate on the simplest task, to play all the notes at precisely the same moment, with one thought, one motion. It takes a few minutes; sometimes, on bad days, it takes all morning. I take my time. But I cannot proceed without this unity of thought, motion, and sound.

Slowly the effort wakes my fingers. Slowly they warm. As the muscles loosen, I break the chords into arpeggios: the same notes, but now spread out, each with its own place, its own demands. Arpeggios make the fingers of both hands work together in different combinations. I play deliberately, building a triangle of sound—fingertip, ear, fingertip—until my hands become aware of each other.

My attention warms and sharpens, and I shape the notes more carefully. I remember now that music is vibration, a disturbance in the air. I remember that music is a kind of breathing, an exchange of energy and excitement. I remember that music is physical, not just in the production of sounds, in the instrumentalist’s technique, but as an experience. Making music changes my body, eliciting shivers, sobs, or the desire to dance. I become aware of myself, of these sensations that lie dormant until music brings them out. And in an instant the pleasure, the effort, the ambition and intensity of playing grip me and shake me awake. I feel as if I’ve been wandering aimlessly until now, as if all the time I’m not practicing, I’m a sleepwalker.

I calm myself and concentrate. Give the sounds time, let the instrument vibrate. I have to hear the sounds I want before I make them, and I have to let the sounds be what they are. Then I have to hear the difference between what I have in mind and what comes from the strings.

It’s easy to get carried away. The grandeur, the depth and beauty of music are always present in the practice room. Holding the guitar, I feel music’s power at my fingertips, as if I might pluck a string and change the world. For centuries people believed that music was the force that moved the planets. Looking into the night sky, astronomers saw the harmony of heaven, and philosophers heard the music of the spheres. Musicians were prophets then, and according to Cicero the most talented might gain entry to heaven while still alive simply “by imitating this harmony on stringed instruments.” Every artist must sometimes believe that art is the doorway to the divine. Perhaps it is. But it’s dangerous for a musician to philosophize instead of practicing. The grandeur of music, to be heard, must be played. When I hold the guitar, I may aspire to play perfect harmonies. But first I have to play well.

I bring myself back to the work at hand. I listen to the strings, while testing fine gradations in the angle, speed, and strength of my touch. I vary the dynamics and articulation, vary the intensity and color of the notes. If I am to play well, I must gather the guitar’s many voices, let each one sing out. After a few more minutes of arpeggios, my fingers grow warm and capable. The notes are clear and distinct, and I play the simple chords again, very softly at first, then louder and more urgently. Again, softly, then filling, expanding, releasing. Once more, until gradually the sounds from the instrument near what I hear in my head.

Listening, drawing sound, motion, and thought together, I find my concentration. My imagination opens and reaches out. And in that reaching I begin to recognize myself. My hands feel like my hands and not the mitts I usually walk around with. I recognize my instrument’s tone; this is how I sound, for now. I recognize my body; I feel alert and able. I feel like a musician again, a classical guitarist. I feel ready to work, ready to play.

“For the past eighty years I have started each day in the same manner,” wrote the cellist Pablo Casals in his memoir, Joys and Sorrows. “I go to the piano, and I play two preludes and fugues of Bach. It fills me with awareness of the wonder of life, with a feeling of the incredible marvel of being a human being.”

Try to describe your experience of music, and you’ll quickly reach the limits of words. Music carries us away, and we grope for the grandest terms in our vocabulary just to hint at the marvel of the flight, the incredible marvel, the wonder. “Each day,” Casals continues, “it is something new, fantastic, and unbelievable.” I imagine him leaning forward in excitement, a round-faced bald man in his eighties, gesturing with his hands, then meeting my eyes to see if I’ve understood. Fantastic and unbelievable. The words say little. But yes, I think I understand.

I’m sitting down to practice, and like Casals, I’m grasping for words to equal my experience. Alone in the practice room, I hold my instrument silently. Every day it is the same task, yet something new. I delve down, seeking what hides waiting in the notes, what lies dormant in myself that music brings to life. I close my eyes and listen for the unheard melody in what I’ve played a hundred times before, the unsuspected openings.

What are the tones, the terms, that unlock music’s power, the pleasure and profundity we experience in listening? I begin to play, leaning forward excitedly and grasping for the right notes, my whole body alive with aspiration. Sounds ring out, ripening for a moment in the air, then dying away. I play the same notes again, reaching for more of the sweetness, the bittersweetness they contain and express. And again the sounds ring out, float across the room, and fall still. Each day, with every note, practicing is the same task, this essential human gesture—reaching out for an ideal, for the grandeur of what you desire, and feeling it slip through your fingers.

Practicing music—practicing anything we really love—we are always at the limit of words, striving for something just beyond our ability to express. Sometimes, when we speak of this work, therefore, we make this the goal, emphasizing the pleasure of reaching out. Practicing, writes Yehudi Menuhin, is “the search for ever greater joy in movement and expression. This is what practice is really about.” But frequently we experience a darker, harsher mood, aware in each moment of what slips away unattained. Then pleasure seems like nourishment for the journey, but it is not what carries us forward. When musicians speak of this experience, they often stress the labor, warning how difficult a path it is, how lonesome and demanding. The great Spanish guitarist Andrés Segovia cautioned that “it is impossible to feign mastery of an instrument, however skillful the impostor may be.” But to attain mastery, if it is possible at all, requires “the stern discipline of lifelong practice.” For the listener, Segovia says, music might seem effortless or divine. But for the musician it is the product of supreme effort and devotion, the feast at the end of the season.

Like every practicing musician, I know both the joy and the hard labor of practice. To hear these sounds emerging from my instrument! And to hear them more clearly, more beautifully in my head than my fingers can ever seem to grasp. Together this pleasure in music and the discipline of practice engage in an endless tussle, a kind of romance. The sense of joy justifies the labor; the labor, I hope, leads to joy. This, at least, is the bargain I quietly make with myself each morning as I sit down. If I just do my work, then pleasure, mastery will follow. Even the greatest artists must make the same bargain. “I was obliged to work hard,” Johann Sebastian Bach is supposed to have said. And I want so much to believe him when he promises that “whoever is equally industrious will succeed just as well.”

Yet as I wrap my arms around the guitar to play, I also hear another voice whispering in my ears. “Whatever efforts we may make,” warned Jean-Jacques Rousseau in his 1767 Dictionary of Music, “we must still be born to the art, otherwise our works can never mount above the insipid.” In every musician’s mind lurks the fear that practicing is merely busywork, that you are either born to your instrument or you are an impostor. Trusting Bach and Segovia, I cling to the belief that my effort will, over time, yield mastery. But this faith sometimes seems naïve, merely a wish. “The capacity for melody is a gift,” asserted Igor Stravinsky. “This means that it is not within our power to develop it by study.” Practice all you want, Rousseau and Stravinsky say, but you will never become a musician if you don’t start out one. Perhaps practice will carry me only so far. Perhaps, as Oscar Wilde put it, “only mediocrities develop.”

I shake out my hands. Outside on the street, the morning commute is over. The workday has begun; school is in session. Only tourists pass by my window now, lumbering up the hill in search of Lombard Street, “the crookedest street in the world.” I walk down this tourist attraction all the time, a pretty, twisting street festooned with flowers. Now, from my chair, I watch a family cluster around a map, Mom, Dad, and two red-haired teenage boys, each pointing in a different direction. They’re just a block from their destination, but they don’t know it, lost within sight of their goal. I feel that way every day.

Practicing is striving; practicing is a romance. But practicing is also a risk, a test of character, a threat of deeply personal failure. I warm up my hands and awaken my ears and imagination, developing skill to equal my experience. I listen and concentrate in an effort to make myself better. Yet every day I collide with my limits, the constraints of my hands, my instrument, and my imagination. Each morning when I sit down, I’m bewildered by a cacophony of voices, encouraging and dismissive, joyous and harsh, each one a little tyrant, each one insisting on its own direction. And I struggle to harmonize them, to find my way between them, uncertain whether this work is worth it or a waste of my time.

Everything I need to make music is here, my hands, my instrument, my imagination, and these notes. For most of their lives Segovia, Casals, Bach, and Stravinsky were also just men sitting alone in a room with these same raw materials, looking out the window at people on the street. Like me, they must at times have wondered how to grasp the immensity of music’s promise in a few simple notes, how to hold fast to their devotion against a cutting doubt that would kill it.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Graceful. . . . A lovely, unique book. . . . A personal journey [that] becomes universal, elevating all in the process.” —Los Angeles Times“A thoughtful and fluid meditation on the subject. . . . [Kurtz] might just compel you to call your old grade-school piano teacher to see if she's taking on any new students.”—The New York Times Book Review “A sensuous, evocative memoir about love lost and regained. . . . Kurtz has gone back to work on his guitar playing, and his devotion seems like a rebirth of self.” —San Francisco Chronicle Book Review“Absorbing . . . [Written] with uncanny sensitivity about his brief career as a professional performer.”—The Wall Street Journal