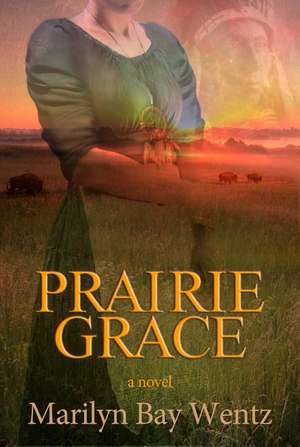

Prairie Grace

Autor Marilyn Bay Wentzen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 noi 2013

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Colorado Book Award (2014)

Thomas had read Gray Wolf’s face well. “It’s not your fault, son. Remember when I told you we can’t blame an entire people for the mistakes of one?”

While the eastern half of the United States is embroiled in Civil War to end slavery, military and political leaders in 1864 Colorado Territory strive to enslave the Native American population they see as impeding settlement. Prairie Grace portrays this clash of cultures through real people, Georgia MacBaye, a throw-caution-to-the-wind frontierswoman, and Gray Wolf, a Cheyenne brave who is thrown into the white world when his uncle, Chief Lean Bear, leaves him on the MacBaye doorstep in hopes that Georgia’s mother, a well-known healer, will be able to save his life.

Despite the hostilities perpetrated by both the U.S. military and Native renegades, there are individuals from both the white and Native populations that speak reason and deal honorably with each other—including Thomas, Georgia’s father, whose ultimate sacrifice brings Gray Wolf to understand grace in a profound way. Destined to be enemies, Georgia and Gray Wolf battle their own and society’s prejudices as they strive to carve out their futures. Packed with history, fast moving and believable, Prairie Grace is a heartbreaking tale of our nation’s past.

While the eastern half of the United States is embroiled in Civil War to end slavery, military and political leaders in 1864 Colorado Territory strive to enslave the Native American population they see as impeding settlement. Prairie Grace portrays this clash of cultures through real people, Georgia MacBaye, a throw-caution-to-the-wind frontierswoman, and Gray Wolf, a Cheyenne brave who is thrown into the white world when his uncle, Chief Lean Bear, leaves him on the MacBaye doorstep in hopes that Georgia’s mother, a well-known healer, will be able to save his life.

Despite the hostilities perpetrated by both the U.S. military and Native renegades, there are individuals from both the white and Native populations that speak reason and deal honorably with each other—including Thomas, Georgia’s father, whose ultimate sacrifice brings Gray Wolf to understand grace in a profound way. Destined to be enemies, Georgia and Gray Wolf battle their own and society’s prejudices as they strive to carve out their futures. Packed with history, fast moving and believable, Prairie Grace is a heartbreaking tale of our nation’s past.

Preț: 126.38 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 190

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.18€ • 25.31$ • 20.13£

24.18€ • 25.31$ • 20.13£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 26 martie-01 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781938467820

ISBN-10: 1938467825

Pagini: 292

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.44 kg

Editura: Koehler Books

ISBN-10: 1938467825

Pagini: 292

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.44 kg

Editura: Koehler Books

Notă biografică

Marilyn Bay Wentz is a third-generation Coloradoan, who grew up on a family farm in northern Colorado. With a degree in journalism, she has written hundreds of news releases and feature stories for her clients and employers, which include Saatchi &Saatchi Advertising Taiwan, the National Farmers Union and the National Bison Association. In addition to operating Prairie Natural Lamb, she currently is editor of two agricultural publications: Bison World and Open Pastures.

Extras

Chapter 1

MacBaye Ranch, Bijou Basin, Colorado Territory, Spring 1862

Georgia MacBaye didn’t dislike gathering eggs or milking the family’s Jersey cow, Blue Bell. It’s just … well … there were so many more exciting things to do. She opened the milking stanchion and released the gentle milk cow. The basket of eggs in one hand and the bucket of milk in the other, Georgia left the barn for the house, its reddish-brown adobe blending in with the prairie. The second story appeared an extension of the imposing bluffs. Her father had chosen the site in the Bijou Basin because the big oak trees reminded him of South Carolina. He told Georgia he hoped it would make her mother feel less homesick. He also had practical reasons for building where he did. The bluffs to the west protected the homestead from the fierce winter blizzards, and the Bijou Creek, just out their backdoor, provided the MacBayes and their stock with water.

This morning, the rugged beauty was not what caught her eye. Snaking single file down the bluffs was a procession of Indian ponies. The pace of the horses and the absence of war paint, told her the Indians meant no harm, but she couldn’t be certain.

Georgia ran toward the house like a startled hare, milk splashing over the sides of the pail, eggs cracking. “Indians … on the bluffs … come look!”

“Ring the dinner bell, Georgia,” her mother Lorraine screamed, panic rising in her voice.

With the alarm sounded, Georgia’s father and brothers, James and Henry, were in the house within minutes.

Georgia’s father pulled down the new Henry repeating rifle from the rack above the parlor fireplace, his work-worn hands slamming the lever down to load a bullet into the chamber. The comfortable parlor with its embroidered doilies and fine furniture was at their backs, as pa, James and Henry stood facing the front door. She read anxiety, not panic, in her father’s weathered face.

“Close the curtains, Loraine,” Pa barked at them, and then softened his tone, “I don’t expect any trouble, but I prefer to be able to see them without them seeing us.”

A few tense minutes later, the Indians pulled their ponies to a stop in front of the MacBaye house. Georgia, who had ignored her mother’s edict to hide in the root cellar, parted the lace-trimmed, gingham curtains that framed the kitchen window. She tossed back wavy auburn hair that had escaped her pony tail. For all she knew, the hair had never made it into the pony tail. She was unconcerned with such details. She wondered if the Indians, who had now made their way into the unfenced pathway at the south end of the main pasture, could see her freckled nose and hazel eyes pressed against the glass, but she just had to get a glimpse of them astride their powerful mounts. Most of the horses sported the bold, spotted coats favored by Indians. Feathers, beads, porcupine quills and snake rattles embellished their buckskin jackets. Naked chests, a shade or two darker than the buckskin they wore, glistened with sweat. Was it nerves, exertion, the warm spring day, or a combination of all three that caused them to sweat? Their presence, their power, their passion, all of it was frightening, yet exhilarating. They were so close that Georgia could not only hear them talking in their strange tongue, but she could also smell the familiar melding of human and horse sweat combined with sagebrush … and what was that smell? Bear fat? The settlers used crushed sagebrush to keep mosquitoes at bay, a trick they’d learned from the Indians. An application of rendered bear fat, she knew, was another Indian way to keep away insects.

Georgia watched as the leader, adorned in a full, flowing feather headdress, dismounted. She guessed him to be her father’s age, in his mid-forties. One of the younger braves also dismounted. She studied the young brave as he lifted a bundle from his travois and hoisted it onto his shoulder. She guessed him to be about nineteen, the age of her older brother James. This brave and the leader, a tall sinewy man with half a dozen jet-black braids flowing down his back, walked toward the MacBaye’s front door, stopping about twenty feet away.

Georgia’s father propped his rifle inside the door, stepped onto the porch and raised his arms, palms open, to make it clear he was unarmed.

“Lean Bear,” Georgia heard the tall man say, patting his chest with his open hand. He paused as the young brave brought the bundle forward and deposited it with great care on the ground. A young Indian in his late teens or early twenties moaned and grimaced in pain amid the bundle of animals skins.

“Lean Bear want white medicine woman make boy well. Good brave sick many days.” Lean Bear gestured toward the injured man. “Indian medicine no work. Buffalo step on brave warrior … big, big hunt, many buffalo run over Gray Wolf.”

White medicine woman? What was Lean Bear saying? Georgia wondered. Before her father could respond, Ma opened the front door and walked to his side. Georgia noted with amusement that even in this tense situation, her mother maintained her perfect, Southern Belle posture.

“He must have internal injuries,” Georgia’s mother said, able to diagnose most any ailment. “Let’s see if he has the fever.”

Ma squatted down beside Gray Wolf, touching his forehead and bare chest with the back of her hand.

“He’s burning up,” she said. “We have to get the heat out of his body. He’s very sick.” She paused. “Let’s get him into the house.”

Georgia’s mother gestured toward the house, and the young brave picked up Gray Wolf and carried him into the MacBaye ranch house. She led them to a room adjacent to the kitchen, pulled down the patchwork quilt and patted the feather mattress. The young brave understood and placed Gray Wolf on the bed with care. The brave who carried Gray Wolf into the house and Lean Bear stepped back as Ma took charge of her new patient. She pressed Gray Wolf’s abdomen at dozens of different angles, eliciting gasps of pain.

Georgia’s mother looked up at the concerned faces, “I think he has internal damage, could be the kidneys. I need to get some dandelion tea down him and make an herbal poultice to extract the fever,” she said, as she headed to the kitchen to prepare the remedies.

Pa let out a sigh of resignation, as he ran a calloused hand through his auburn hair. Georgia knew he was thinking what she was. Her mother’s medical knowledge was recognized by the white settlers in the area. Now, it seemed the Indians—at least these Indians—had also learned of her reputation as a healer.

Lean Bear and the young brave who had carried Gray Wolf into the house watched and waited, as if eager to see what the white medicine woman would do. Ma moved in and out of the room, applying the poultices she created. Over the past few years, Ma had instructed Georgia which herb combinations to stuff in the cheesecloth pouches to reduce fever, or to calm a queasy stomach, or any other of dozens of maladies. Georgia’s mother lifted her patient’s head so that he could sip the nourishing dandelion tea. Georgia knew that in any other setting, her mother would have acted with much greater caution, but when it came to the healing arts, there was no one better, nor more certain of what to do than Loraine MacBaye. And now, Georgia, who at age fifteen had learned much of her mother’s healing technique, worked alongside her mother.

At mid-day, Ma sent Georgia to kill and dress a chicken. Georgia always hated killing a faithful layer when her producing days ended, but she didn’t think twice about scooping up the cocky, young red rooster that got more aggressive each time she collected eggs. She broke his neck with a precise, two-handed jerked so that he felt nothing when his head met with the axe. She took the dressed and plucked rooster into the kitchen where they would boil the carcass for hours to make nourishing bone broth for Gray Wolf. Georgia chuckled to herself; Ma believed the South American saying she had once read, “A good bone broth can even bring the dead back to life.”

Georgia glanced out at the corn field and saw the faithful team of oxen, “Daddy, you left the team in the field,” said Georgia. He darted out the door toward the field he had been plowing hours ago when she rang the dinner bell to alert the men Indians approached.

Upon further observation, Georgia noticed the oxen stood heads down, having moved no more than fifty feet from where her father had left them that morning. She mused over the irony that her father had adopted the practice of Western plainsmen, who used oxen, rather than horses, for fieldwork. Georgia knew she had acquired her love of horses from him, but she knew that both of them would have to admit the patient, plodding oxen were the better choice for plowing and bringing in a crop. A pair of horses left alone for hours would have torn off their harness, ripped up the newly sown field, and disappeared. She smiled as she watched her father lead the gentle, forgiving oxen pair off to be unhitched, watered, and secured in the sturdy corrals he and her brothers had built when they first settled the place.

Only now did she notice the greening prairie grass and the ankle-high winter wheat that peaked out beneath the tufts of dirty snow from the late spring storm. An impending explosion of green grasses, dotted with yellow, red, and purple wildflowers would soon turn the winter barrenness into a landscape to nourish man and beast, refreshing body and soul. Her thoughts this morning had been on training the sassy little sorrel filly her father had bought from a neighbor. Instead, she had spent the day helping her mother heal an Indian brave.

As the sun sunk low on the horizon, Georgia saw Pa hurrying back to the house.

“They’re gone, Thomas,” Ma said.

“Who’s gone?” Pa asked, still puffing as he entered the house.

“The Indians,” her mother said. “Well, not all of them. They left Gray Wolf, of course. He’s better but in no condition to travel.”

“Did they say when they would be back?” he asked.

“No. I was going about my business, and I didn’t even notice when they left,” she said.

“Well, if that doesn’t beat all,” Pa laughed. “When we decided to move West, I worried about how to defend my family and my stock from Indians, but I never worried about inheriting one!”

----------

Five days later, Gray Wolf came out of his delirium. It seemed the poor boy had no memory of how he got to the MacBaye Ranch or why he was there. He lunged at the door in a feeble attempt to escape, but his weakened state and considerable pain made it easy for Pa to restrain him.

“Easy there, young feller,” Thomas soothed. “Fetch him something to eat, so he knows we mean him no harm.”

Georgia ran to the springhouse at the edge of the creek. She lifted the crock out of the cool water, removed the cork lid, and poured the creamy milk into a tin cup. She was grateful that Blue Bell had freshened a few weeks earlier when she gave birth to her second calf. There was enough milk for all of them to have their fill, and there was plenty of cream left over to make butter. Yes, butter, she got a slap of that as well. Returning to the house, she slathered the butter on a piece of bread fresh from the oven that morning.

Taking a breath and slowing her pace, so as not to frighten Gray Wolf and send him into another fit, she presented him with the cup of milk. He smelled it, turned the cup around in his hands, and then tasted it by dipping a finger into the milk and putting it to his lips.

“Go on there and drink that rich Jersey milk, it’ll do ya some good,” Thomas smiled. “You may not be used to drinking milk, so take it easy, son.”

Next Georgia handed him the slab of bread slathered in butter. “Try this,” she coaxed. Again, he smelled the food and touched it with his finger. Georgia nodded approval. He pulled off a bread crust and popped it in his mouth. A smile appeared at the corners of his lips. Soon, both the milk and the bread disappeared.

That night, Pa slept in Gray Wolf’s room to ensure he didn’t harm himself or them. The next day, the brave ate everything offered him without reservation. “Please” and “more” seemed the extent of his English vocabulary until the following evening when he seemed to be trying to piece together the circumstances that brought him to the MacBayes.

“Where Lean Bear?” Gray Wolf asked.

“Lean Bear brought you here to see white medicine woman,” Pa said gesturing toward Ma. “She made you well.”

Gray Wolf nodded. “I go now. Find Lean Bear.”

“You are still not strong, Gray Wolf,” Pa said. “We will help you get better.”

“Trust us, Gray Wolf,” Georgia added, smiling.

Gray Wolf laid back on his bed, nodding, “Find Lean Bear soon.”

The next morning, Georgia decided Gray Wolf was strong enough to eat with them at the dining room table. She guided him to a chair, and patted the seat. He sat, but when he seemed uncertain what to do, Georgia noticed that he looked to her for subtle signals. When she folded her hands in her lap, Gray Wolf did likewise. Out of the corner of her eye, Georgia saw him put his hands on either side of his soup bowl, as if preparing to raise it to his mouth to drink his soup. She hastened to pick up her spoon, fill it with soup, and raise it to her lips. He imitated her.

Gray Wolf never again mentioned leaving the ranch to find Lean Bear.

----------

Days turned into weeks. Georgia noticed, blushing, that Gray Wolf had put on weight and muscle. He was strong and virile. The herbs and bone broths, along with the fall’s hearty ranch diet of garden potatoes, carrots, beets, greens, wild plums, eggs, beef and game had turned his body from one that looked like skin stretched over bones to that of a robust young man. His skin was a creamy brown, the hue of stout coffee with plenty of cream. His hair hung just below his shoulders. Most of the Indians Georgia had seen had jet black hair, but Gray Wolf’s was more a dark brown, like coffee without the cream, she thought. He was the same height as James and her father, “a good amount tallerin average,” as Pa had once described his height, yet Gray Wolf was not as stout as the MacBaye men. He was muscled yet lithe, like a Pronghorn antelope. Georgia imagined he could run almost as fast and long as a Pronghorn.

Fall was a busy time, as Georgia’s family worked from dawn to dust to harvest, store and dry the food that would sustain them and their livestock over the winter. The MacBaye men cut hay, left it in the field to dry for several days, then used the wagon and oxen to haul it to the barn and hoist it into the loft. They picked ears of corn and laid them in the yard to dry. Later, Georgia and her mother would grind the corn between stones to make cornmeal for baking, leaving the remaining corn to feed to the chickens, horses and cows when the cold weather made it difficult for the animals to maintain their body weight.

The men cut, bundled and then threshed the wheat to separate the grain kernels from the stalk. The MacBayes put the largest, fully-formed wheat kernels in the root cellar in burlap sacks. They would grind the kernels into flour to use for making bread and pancakes, as it was needed. The rest was their seed for the next crop. They would plant it in the fall. If there were excess sacks of wheat, the MacBayes would take them to sell on the annual supply trip to Denver. Nothing went to waste. Inferior wheat kernels became animal feed. The chaff, also called straw, became animal bedding for cold, wet times. Pa, James and Henry made the backbreaking work look easy, she thought. Though the tasks were unfamiliar to Gray Wolf, he was a willing student and a hard worker.

Georgia would have preferred to work in the fields with her father and brothers, but tradition kept her closer to home. She helped her mother harvest potatoes, carrots, onions, beets and winter squashes and stashed them in the root cellar. She did enjoy cutting, washing and drying the many herbs her mother cultivated for healing and for flavoring food. She hated to admit it, but helping her mom boil down wild berries and plums with honey to make jams and jellies was not a bad task. She teased her brothers and made them do things for her in exchange for tastes of the sweet fruity preserves.

Georgia thought of no reason not to include Gray Wolf in her practical jokes. That afternoon she stood at the stovetop stirring a delectable smelling sauce. Gray Wolf had just come into the house from helping do evening chores, and, like any hungry man, the cooking sauce drew him into the kitchen. He plunked down at the table, a chunky but finely hewn piece of wood taken from a downed Cottonwood at the creek the first winter they spent out west. Georgia’s pa was a good carpenter, and he had insisted on fashioning a long table with benches on either side to seat the family and any guests they might have.

“Do you want some hot green chile sauce?” Georgia drawled, a mischievous gleam in her eye.

He nodded, and she scooped a ladle-full into a bowl. He took his time, blowing to cool the stew, as he had learned to do at the MacBaye dinner table. A few seconds later, he put a big spoonful in his mouth and swallowed. Georgia could no longer contain herself. She spun around to look at Gray Wolf, who reddened, choked and coughed. Perhaps she shouldn’t have done it, but it was the same joke the Mexicans who’d built the MacBaye’s adobe ranch house had once played on her. She knew the sauce was eaten as a condiment, but to an innocent who thought it was a stew, there would be several minutes of extreme discomfort, as Gray Wolf demonstrated by fanning what must have felt like flames coming from his mouth

“I understand why the Mexicans say this sauce keeps away sickness,” her father said the first time he tried it. “If you eat it, your breath is so strong not even your horse will come near you.”

Gray Wolf seemed shocked she had duped him until he saw her shoulders shake from her hidden laughter. Soon they both laughed. Georgia hoped, no, dreaded, no, hoped he would pay her back.

MacBaye Ranch, Bijou Basin, Colorado Territory, Spring 1862

Georgia MacBaye didn’t dislike gathering eggs or milking the family’s Jersey cow, Blue Bell. It’s just … well … there were so many more exciting things to do. She opened the milking stanchion and released the gentle milk cow. The basket of eggs in one hand and the bucket of milk in the other, Georgia left the barn for the house, its reddish-brown adobe blending in with the prairie. The second story appeared an extension of the imposing bluffs. Her father had chosen the site in the Bijou Basin because the big oak trees reminded him of South Carolina. He told Georgia he hoped it would make her mother feel less homesick. He also had practical reasons for building where he did. The bluffs to the west protected the homestead from the fierce winter blizzards, and the Bijou Creek, just out their backdoor, provided the MacBayes and their stock with water.

This morning, the rugged beauty was not what caught her eye. Snaking single file down the bluffs was a procession of Indian ponies. The pace of the horses and the absence of war paint, told her the Indians meant no harm, but she couldn’t be certain.

Georgia ran toward the house like a startled hare, milk splashing over the sides of the pail, eggs cracking. “Indians … on the bluffs … come look!”

“Ring the dinner bell, Georgia,” her mother Lorraine screamed, panic rising in her voice.

With the alarm sounded, Georgia’s father and brothers, James and Henry, were in the house within minutes.

Georgia’s father pulled down the new Henry repeating rifle from the rack above the parlor fireplace, his work-worn hands slamming the lever down to load a bullet into the chamber. The comfortable parlor with its embroidered doilies and fine furniture was at their backs, as pa, James and Henry stood facing the front door. She read anxiety, not panic, in her father’s weathered face.

“Close the curtains, Loraine,” Pa barked at them, and then softened his tone, “I don’t expect any trouble, but I prefer to be able to see them without them seeing us.”

A few tense minutes later, the Indians pulled their ponies to a stop in front of the MacBaye house. Georgia, who had ignored her mother’s edict to hide in the root cellar, parted the lace-trimmed, gingham curtains that framed the kitchen window. She tossed back wavy auburn hair that had escaped her pony tail. For all she knew, the hair had never made it into the pony tail. She was unconcerned with such details. She wondered if the Indians, who had now made their way into the unfenced pathway at the south end of the main pasture, could see her freckled nose and hazel eyes pressed against the glass, but she just had to get a glimpse of them astride their powerful mounts. Most of the horses sported the bold, spotted coats favored by Indians. Feathers, beads, porcupine quills and snake rattles embellished their buckskin jackets. Naked chests, a shade or two darker than the buckskin they wore, glistened with sweat. Was it nerves, exertion, the warm spring day, or a combination of all three that caused them to sweat? Their presence, their power, their passion, all of it was frightening, yet exhilarating. They were so close that Georgia could not only hear them talking in their strange tongue, but she could also smell the familiar melding of human and horse sweat combined with sagebrush … and what was that smell? Bear fat? The settlers used crushed sagebrush to keep mosquitoes at bay, a trick they’d learned from the Indians. An application of rendered bear fat, she knew, was another Indian way to keep away insects.

Georgia watched as the leader, adorned in a full, flowing feather headdress, dismounted. She guessed him to be her father’s age, in his mid-forties. One of the younger braves also dismounted. She studied the young brave as he lifted a bundle from his travois and hoisted it onto his shoulder. She guessed him to be about nineteen, the age of her older brother James. This brave and the leader, a tall sinewy man with half a dozen jet-black braids flowing down his back, walked toward the MacBaye’s front door, stopping about twenty feet away.

Georgia’s father propped his rifle inside the door, stepped onto the porch and raised his arms, palms open, to make it clear he was unarmed.

“Lean Bear,” Georgia heard the tall man say, patting his chest with his open hand. He paused as the young brave brought the bundle forward and deposited it with great care on the ground. A young Indian in his late teens or early twenties moaned and grimaced in pain amid the bundle of animals skins.

“Lean Bear want white medicine woman make boy well. Good brave sick many days.” Lean Bear gestured toward the injured man. “Indian medicine no work. Buffalo step on brave warrior … big, big hunt, many buffalo run over Gray Wolf.”

White medicine woman? What was Lean Bear saying? Georgia wondered. Before her father could respond, Ma opened the front door and walked to his side. Georgia noted with amusement that even in this tense situation, her mother maintained her perfect, Southern Belle posture.

“He must have internal injuries,” Georgia’s mother said, able to diagnose most any ailment. “Let’s see if he has the fever.”

Ma squatted down beside Gray Wolf, touching his forehead and bare chest with the back of her hand.

“He’s burning up,” she said. “We have to get the heat out of his body. He’s very sick.” She paused. “Let’s get him into the house.”

Georgia’s mother gestured toward the house, and the young brave picked up Gray Wolf and carried him into the MacBaye ranch house. She led them to a room adjacent to the kitchen, pulled down the patchwork quilt and patted the feather mattress. The young brave understood and placed Gray Wolf on the bed with care. The brave who carried Gray Wolf into the house and Lean Bear stepped back as Ma took charge of her new patient. She pressed Gray Wolf’s abdomen at dozens of different angles, eliciting gasps of pain.

Georgia’s mother looked up at the concerned faces, “I think he has internal damage, could be the kidneys. I need to get some dandelion tea down him and make an herbal poultice to extract the fever,” she said, as she headed to the kitchen to prepare the remedies.

Pa let out a sigh of resignation, as he ran a calloused hand through his auburn hair. Georgia knew he was thinking what she was. Her mother’s medical knowledge was recognized by the white settlers in the area. Now, it seemed the Indians—at least these Indians—had also learned of her reputation as a healer.

Lean Bear and the young brave who had carried Gray Wolf into the house watched and waited, as if eager to see what the white medicine woman would do. Ma moved in and out of the room, applying the poultices she created. Over the past few years, Ma had instructed Georgia which herb combinations to stuff in the cheesecloth pouches to reduce fever, or to calm a queasy stomach, or any other of dozens of maladies. Georgia’s mother lifted her patient’s head so that he could sip the nourishing dandelion tea. Georgia knew that in any other setting, her mother would have acted with much greater caution, but when it came to the healing arts, there was no one better, nor more certain of what to do than Loraine MacBaye. And now, Georgia, who at age fifteen had learned much of her mother’s healing technique, worked alongside her mother.

At mid-day, Ma sent Georgia to kill and dress a chicken. Georgia always hated killing a faithful layer when her producing days ended, but she didn’t think twice about scooping up the cocky, young red rooster that got more aggressive each time she collected eggs. She broke his neck with a precise, two-handed jerked so that he felt nothing when his head met with the axe. She took the dressed and plucked rooster into the kitchen where they would boil the carcass for hours to make nourishing bone broth for Gray Wolf. Georgia chuckled to herself; Ma believed the South American saying she had once read, “A good bone broth can even bring the dead back to life.”

Georgia glanced out at the corn field and saw the faithful team of oxen, “Daddy, you left the team in the field,” said Georgia. He darted out the door toward the field he had been plowing hours ago when she rang the dinner bell to alert the men Indians approached.

Upon further observation, Georgia noticed the oxen stood heads down, having moved no more than fifty feet from where her father had left them that morning. She mused over the irony that her father had adopted the practice of Western plainsmen, who used oxen, rather than horses, for fieldwork. Georgia knew she had acquired her love of horses from him, but she knew that both of them would have to admit the patient, plodding oxen were the better choice for plowing and bringing in a crop. A pair of horses left alone for hours would have torn off their harness, ripped up the newly sown field, and disappeared. She smiled as she watched her father lead the gentle, forgiving oxen pair off to be unhitched, watered, and secured in the sturdy corrals he and her brothers had built when they first settled the place.

Only now did she notice the greening prairie grass and the ankle-high winter wheat that peaked out beneath the tufts of dirty snow from the late spring storm. An impending explosion of green grasses, dotted with yellow, red, and purple wildflowers would soon turn the winter barrenness into a landscape to nourish man and beast, refreshing body and soul. Her thoughts this morning had been on training the sassy little sorrel filly her father had bought from a neighbor. Instead, she had spent the day helping her mother heal an Indian brave.

As the sun sunk low on the horizon, Georgia saw Pa hurrying back to the house.

“They’re gone, Thomas,” Ma said.

“Who’s gone?” Pa asked, still puffing as he entered the house.

“The Indians,” her mother said. “Well, not all of them. They left Gray Wolf, of course. He’s better but in no condition to travel.”

“Did they say when they would be back?” he asked.

“No. I was going about my business, and I didn’t even notice when they left,” she said.

“Well, if that doesn’t beat all,” Pa laughed. “When we decided to move West, I worried about how to defend my family and my stock from Indians, but I never worried about inheriting one!”

----------

Five days later, Gray Wolf came out of his delirium. It seemed the poor boy had no memory of how he got to the MacBaye Ranch or why he was there. He lunged at the door in a feeble attempt to escape, but his weakened state and considerable pain made it easy for Pa to restrain him.

“Easy there, young feller,” Thomas soothed. “Fetch him something to eat, so he knows we mean him no harm.”

Georgia ran to the springhouse at the edge of the creek. She lifted the crock out of the cool water, removed the cork lid, and poured the creamy milk into a tin cup. She was grateful that Blue Bell had freshened a few weeks earlier when she gave birth to her second calf. There was enough milk for all of them to have their fill, and there was plenty of cream left over to make butter. Yes, butter, she got a slap of that as well. Returning to the house, she slathered the butter on a piece of bread fresh from the oven that morning.

Taking a breath and slowing her pace, so as not to frighten Gray Wolf and send him into another fit, she presented him with the cup of milk. He smelled it, turned the cup around in his hands, and then tasted it by dipping a finger into the milk and putting it to his lips.

“Go on there and drink that rich Jersey milk, it’ll do ya some good,” Thomas smiled. “You may not be used to drinking milk, so take it easy, son.”

Next Georgia handed him the slab of bread slathered in butter. “Try this,” she coaxed. Again, he smelled the food and touched it with his finger. Georgia nodded approval. He pulled off a bread crust and popped it in his mouth. A smile appeared at the corners of his lips. Soon, both the milk and the bread disappeared.

That night, Pa slept in Gray Wolf’s room to ensure he didn’t harm himself or them. The next day, the brave ate everything offered him without reservation. “Please” and “more” seemed the extent of his English vocabulary until the following evening when he seemed to be trying to piece together the circumstances that brought him to the MacBayes.

“Where Lean Bear?” Gray Wolf asked.

“Lean Bear brought you here to see white medicine woman,” Pa said gesturing toward Ma. “She made you well.”

Gray Wolf nodded. “I go now. Find Lean Bear.”

“You are still not strong, Gray Wolf,” Pa said. “We will help you get better.”

“Trust us, Gray Wolf,” Georgia added, smiling.

Gray Wolf laid back on his bed, nodding, “Find Lean Bear soon.”

The next morning, Georgia decided Gray Wolf was strong enough to eat with them at the dining room table. She guided him to a chair, and patted the seat. He sat, but when he seemed uncertain what to do, Georgia noticed that he looked to her for subtle signals. When she folded her hands in her lap, Gray Wolf did likewise. Out of the corner of her eye, Georgia saw him put his hands on either side of his soup bowl, as if preparing to raise it to his mouth to drink his soup. She hastened to pick up her spoon, fill it with soup, and raise it to her lips. He imitated her.

Gray Wolf never again mentioned leaving the ranch to find Lean Bear.

----------

Days turned into weeks. Georgia noticed, blushing, that Gray Wolf had put on weight and muscle. He was strong and virile. The herbs and bone broths, along with the fall’s hearty ranch diet of garden potatoes, carrots, beets, greens, wild plums, eggs, beef and game had turned his body from one that looked like skin stretched over bones to that of a robust young man. His skin was a creamy brown, the hue of stout coffee with plenty of cream. His hair hung just below his shoulders. Most of the Indians Georgia had seen had jet black hair, but Gray Wolf’s was more a dark brown, like coffee without the cream, she thought. He was the same height as James and her father, “a good amount tallerin average,” as Pa had once described his height, yet Gray Wolf was not as stout as the MacBaye men. He was muscled yet lithe, like a Pronghorn antelope. Georgia imagined he could run almost as fast and long as a Pronghorn.

Fall was a busy time, as Georgia’s family worked from dawn to dust to harvest, store and dry the food that would sustain them and their livestock over the winter. The MacBaye men cut hay, left it in the field to dry for several days, then used the wagon and oxen to haul it to the barn and hoist it into the loft. They picked ears of corn and laid them in the yard to dry. Later, Georgia and her mother would grind the corn between stones to make cornmeal for baking, leaving the remaining corn to feed to the chickens, horses and cows when the cold weather made it difficult for the animals to maintain their body weight.

The men cut, bundled and then threshed the wheat to separate the grain kernels from the stalk. The MacBayes put the largest, fully-formed wheat kernels in the root cellar in burlap sacks. They would grind the kernels into flour to use for making bread and pancakes, as it was needed. The rest was their seed for the next crop. They would plant it in the fall. If there were excess sacks of wheat, the MacBayes would take them to sell on the annual supply trip to Denver. Nothing went to waste. Inferior wheat kernels became animal feed. The chaff, also called straw, became animal bedding for cold, wet times. Pa, James and Henry made the backbreaking work look easy, she thought. Though the tasks were unfamiliar to Gray Wolf, he was a willing student and a hard worker.

Georgia would have preferred to work in the fields with her father and brothers, but tradition kept her closer to home. She helped her mother harvest potatoes, carrots, onions, beets and winter squashes and stashed them in the root cellar. She did enjoy cutting, washing and drying the many herbs her mother cultivated for healing and for flavoring food. She hated to admit it, but helping her mom boil down wild berries and plums with honey to make jams and jellies was not a bad task. She teased her brothers and made them do things for her in exchange for tastes of the sweet fruity preserves.

Georgia thought of no reason not to include Gray Wolf in her practical jokes. That afternoon she stood at the stovetop stirring a delectable smelling sauce. Gray Wolf had just come into the house from helping do evening chores, and, like any hungry man, the cooking sauce drew him into the kitchen. He plunked down at the table, a chunky but finely hewn piece of wood taken from a downed Cottonwood at the creek the first winter they spent out west. Georgia’s pa was a good carpenter, and he had insisted on fashioning a long table with benches on either side to seat the family and any guests they might have.

“Do you want some hot green chile sauce?” Georgia drawled, a mischievous gleam in her eye.

He nodded, and she scooped a ladle-full into a bowl. He took his time, blowing to cool the stew, as he had learned to do at the MacBaye dinner table. A few seconds later, he put a big spoonful in his mouth and swallowed. Georgia could no longer contain herself. She spun around to look at Gray Wolf, who reddened, choked and coughed. Perhaps she shouldn’t have done it, but it was the same joke the Mexicans who’d built the MacBaye’s adobe ranch house had once played on her. She knew the sauce was eaten as a condiment, but to an innocent who thought it was a stew, there would be several minutes of extreme discomfort, as Gray Wolf demonstrated by fanning what must have felt like flames coming from his mouth

“I understand why the Mexicans say this sauce keeps away sickness,” her father said the first time he tried it. “If you eat it, your breath is so strong not even your horse will come near you.”

Gray Wolf seemed shocked she had duped him until he saw her shoulders shake from her hidden laughter. Soon they both laughed. Georgia hoped, no, dreaded, no, hoped he would pay her back.

Descriere

Thomas had read Gray Wolf’s face well. “It’s not your fault, son. Remember when I told you we can’t blame an entire people for the mistakes of one?”

While the eastern half of the United States is embroiled in Civil War to end slavery, military and political leaders in 1864 Colorado Territory strive to enslave the Native American population they see as impeding settlement. Prairie Grace portrays this clash of cultures through real people, Georgia MacBaye, a throw-caution-to-the-wind frontierswoman, and Gray Wolf, a Cheyenne brave who is thrown into the white world when his uncle, Chief Lean Bear, leaves him on the MacBaye doorstep in hopes that Georgia’s mother, a well-known healer, will be able to save his life.

Despite the hostilities perpetrated by both the U.S. military and Native renegades, there are individuals from both the white and Native populations that speak reason and deal honorably with each other—including Thomas, Georgia’s father, whose ultimate sacrifice brings Gray Wolf to understand grace in a profound way. Destined to be enemies, Georgia and Gray Wolf battle their own and society’s prejudices as they strive to carve out their futures. Packed with history, fast moving and believable, Prairie Grace is a heartbreaking tale of our nation’s past.

While the eastern half of the United States is embroiled in Civil War to end slavery, military and political leaders in 1864 Colorado Territory strive to enslave the Native American population they see as impeding settlement. Prairie Grace portrays this clash of cultures through real people, Georgia MacBaye, a throw-caution-to-the-wind frontierswoman, and Gray Wolf, a Cheyenne brave who is thrown into the white world when his uncle, Chief Lean Bear, leaves him on the MacBaye doorstep in hopes that Georgia’s mother, a well-known healer, will be able to save his life.

Despite the hostilities perpetrated by both the U.S. military and Native renegades, there are individuals from both the white and Native populations that speak reason and deal honorably with each other—including Thomas, Georgia’s father, whose ultimate sacrifice brings Gray Wolf to understand grace in a profound way. Destined to be enemies, Georgia and Gray Wolf battle their own and society’s prejudices as they strive to carve out their futures. Packed with history, fast moving and believable, Prairie Grace is a heartbreaking tale of our nation’s past.

Premii

- Colorado Book Award Finalist, 2014