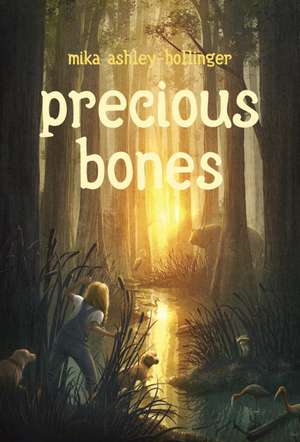

Precious Bones

Autor Mika Ashley-Hollingeren Limba Engleză Paperback – 25 mar 2013 – vârsta de la 9 până la 12 ani

It's summer, and Bones is busy hunting and fishing with her best friend, Little Man. But then two Yankee real estate agents trespass on her family's land, and Nolay scares them off with his gun. When a storm blows in and Bones and Little Man uncover something horrible at the edge of the Loo-chee swamp, the evidence of foul play points to Nolay. The only person that can help Nolay is Sheriff LeRoy, who's as slow as pond water. Bones is determined to take matters into her own hands. If it takes a miracle, then a miracle is what she will deliver.

Preț: 55.81 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 84

Preț estimativ în valută:

10.68€ • 11.11$ • 8.82£

10.68€ • 11.11$ • 8.82£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307930705

ISBN-10: 030793070X

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 130 x 193 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Yearling Books

ISBN-10: 030793070X

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 130 x 193 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Yearling Books

Notă biografică

MIKA ASHLEY-HOLLINGER grew up in the Florida swamps in the tiny community of Micco and now lives in Hawaii where she runs an exotic plants landscaping business. This is her first novel.

Extras

The Storm

The sweltering month of July was gradually melting into August. Baby alligators were busy pecking their way out of their eggs when the biggest storm of the summer of 1949 blew into our lives. I was standing in the middle of our living room floor, cool brown water swirling over my feet and reaching nearly to the tops of my skinny ten-year-old ankles. The morning sun was just peeking in through our picture window, painting shiny rainbows across the water's dull surface.

My daddy, Nolay, paced slowly from one end of the room to the other. He was just as barefooted as me because there was no reason to be wearing shoes inside your house when it was full of water. Each small step sent ripples of coffee-colored water circling around the legs of what pieces of furniture we hadn't stacked on top of each other. Nolay solemnly raised his arms in the air and declared, "We live in the womb of the world! It's the womb of the world. Any fool can see it's God's womb of the world!"

Like a contented cat, Mama was curled up on the couch. I don't think she was really that contented, she just didn't have any choice but to sit there. Her slender arms wrapped around her legs and hugged them close to her body. Her head rested on her knees; only her eyes moved back and forth as she watched my daddy's every move.

Out of the corner of my eye I saw something dark and shiny slither along the side of the wall right behind the couch. I kept my mouth shut, because if there was one thing Mama didn't like, especially inside her house, it was snakes.

I was not quite sure what a womb was, but if Nolay said we lived in one, then it must be true. My daddy was about the smartest man I ever did know. I hadn't met very many men, but of the ones I had, he was about the smartest. He was a true man of vision.

He'd had the vision to nestle our house between a glorious Florida swamp and a long stretch of sandy scrub palmetto laced with majestic old pines. Although Mama often pointed out that his vision blurred when it came to the exact location. "If you had put this house a hundred yards closer to the county road we would have electricity. We would have a icebox and a sewing machine," Mama would say.

Nolay would shake his shaggy black curls and reply, "Lori, Honey Girl, you know I don't want to be any closer to that dang county road!"

Honey Girl was my daddy's nickname for Mama because her blond hair dripped down her back and around her shoulders like golden honey.

"If I could, I would have put us on a float right out in the middle of the swamp. But don't you fret, one day I'll buy my own durn electric poles and stick 'em in the ground myself."

But Mama couldn't deny that Nolay had had the vision to build our house on a strip of land at least a foot above water level. It only flooded when the heavy summer rains came. It really wasn't that bad; sometimes the water just seeped in and covered our floor with a fine, shiny mist.

Our house also had a flat tar-paper roof because, as Nolay had explained, "No matter how big a storm comes through, this roof will stay put. You go puttin' one of those pointed roofs on and sure as shootin' the first hurricane will take it off. Same thing goes for puttin' your house up on stilts." Yes, sir, Nolay was a true man of vision.

At any rate, all the excitement had started the day before. Me and Mama had just returned from a Saturday trip to town and were inside the house putting away groceries when Nolay called us.

"Honey Girl, Bones, y'all come on out here and take a look at this." He was standing in the yard looking east. That was where the Atlantic Ocean lived, and most of our storms came from that direction.

What I saw filled up the horizon. It looked like a massive black jellyfish. The cloud floated just above the ground and moved with fierce intent, heading directly toward us. The three of us stood like fence posts until Nolay said, "That's a mighty big storm coming our way. Y'all get the animals inside the house."

Me and Mama sprang to life, called the dogs, and looked for the cats. Half an hour later I made a final count: three dogs, five cats, one raccoon, one pig, and one goat, everyone accounted for. As I ran out the door I yelled over my shoulder, "Mama, I'm goin' out to help Nolay."

Nolay had just closed the door to the chicken coop. Old Ikibob Rooster sensed something was up and already had his brood cornered in one end of the coop. By the time we headed for the house, that jellyfish cloud was nearly on top of us. It hungrily gobbled up the silver-blue day and turned it into gloomy darkness.

As it hovered above us, it looked as if God reached his long pointy-finger down from heaven and ripped a huge gash in the stomach of that jellyfish. Gray sheets of water fell furiously to the ground. Cannonballs of thunder crashed and rolled angrily over the swamps. Like gigantic knives, silver streaks of lightning sliced through the darkness and stabbed the earth.

Me and all the animals were wide-eyed and looking for something to crawl under. Except for the flashes of lightning and the soft flicker of our kerosene lamps, our house was as black as the inside of a cow. I had never been inside a cow, but I imagined this was how totally dark it would be.

Our summer storms usually dumped a ton of water in the swamps. Water was precious to swamps; they needed it to stay alive. Sometimes a thin layer of water would run through our house, but this storm was big, and it was angry. The swamp quickly filled and began to leak out over its shallow edges. The little sliver of land our house sat on was soaked up like a dirty dishrag. Swamp water, along with some of its inhabitants, seeped under doorways and through cracks and crannies. Water came from every direction; it slid down the sides of our walls and dripped from the ceiling in endless streams.

Nolay began to bark out instructions. "Stack up them chairs, put a quilt on the table and get the cats up there, put the dogs in our bed, get the pig and goat into the washtub! Bones, do something with that dang crazy raccoon!"

When the three of us sat huddled together on the couch, Nolay murmured, "Don't worry about nothing, it's just a little water. It's just a storm, a big storm, but it's not a hurricane. The roof will stay on."

It was too wet and too dark for us to make it to a bedroom, so we decided it was best to just stay put right there on the couch. Nestled between the two of them, I fell asleep with the assurance that Nolay knew about hurricanes. The one in 1935 had blown his family home clear down to the ground. That house sat not ten feet away from the very spot we were at right now. About the only thing left was a pile of bricks where the chimney had stood, the artesian well that we still got our water from, and a mammoth mango tree.

On occasion, when things would get out of hand, like they were right now, Mama would look over to Nolay and say, "Why did you build our house next to one that blew down in a storm? You could have put us on higher ground."

But my daddy, with his vision and truthfulness, would reply, "Because this is where my home is and always will be. Don't worry, Honey Girl, I guarantee this house ain't gonna blow down."

Nolay's real name was Seminole, but no one ever called him that. His daddy, who was Miccosukee Indian, named him in honor of their kindred tribe. Nolay lived up to the true meaning of his name, which was "runaway; wild one."

All night long that storm pounded us with huge fists of water. At the break of dawn, as we waded through our living room, the first words out of Nolay's mouth were "Well, am I right or am I right? I said the dang roof would stay on, and it did!"

Nolay was right about the roof staying on, and it wouldn't be a concern any longer. Our real troubles would be coming all too soon.

Saving the Day

Mama refused to get off the couch, even after Nolay offered her a piggyback ride. She hugged her legs close to her body and kept her chin on her knees. She was not about to stick her feet in that dirty brown water. Just as Mama turned her head sideways, a little black snake wriggled along the side of the wall. She pointed and said, "My goodness, what is that? Is that a snake inside our house?"

I quickly waded over to it. "It's only a baby. It's scared and it's just trying to find its way back outside."

Mama groaned. "And I want it to go back outside." She looked at Nolay. "What else has the womb of the world dumped inside our house?"

"Lori, that's just a little ol' baby, it squeezed in through a crack. Don't worry; they ain't nothing in here but some harmless water."

I crept behind the couch and gingerly picked the snake up by its slippery little tail. I turned to Mama and said, "Look, Mama, it ain't much bigger than a fat old fishin' worm. It's probably one of Old Blackie's babies. I'll just take it outside where it belongs." Blackie was our resident blacksnake. She lived in the giant mango tree in our backyard.

Armed with Crisco cans and mason jars, I was ready to go outside and catch the bounty of tadpoles, minnows, and whatever else the swamp had spilled out on our driveway. Or what we called our driveway; it was actually a two-rut dirt road with ditches cut in on both sides. After every big summer rain I took it on myself to go out and catch as many living things as I could and dump them into the pond in our front yard. Of course, a fair amount of the creatures I would be picking up that day came from the pond in our front yard, but I felt it was my duty to save as many as I could.

With a great display of authority I dropped the pathetic little snake in my Crisco can and made my way to the front door. I whistled, and our three dogs, Nippy the raccoon, and Pearl the pig almost knocked me down as they clambered toward the door. Harry the goat had made himself quite comfortable in the washtub, his head hung over the rim and his big glassy eyes looking forlornly in my direction.

I strapped my trusty Roy Rogers cap pistols around my waist and opened the front door. I was getting too old to still be playing with cap pistols, but they just felt like a couple of friends hanging out with me. Nolay called out, "Bones, you watch out for snakes. Take a hoe or machete with you. They bound to be lookin' for dry land. And keep your eye on those dang dogs; the fools will stick their nose right on top of a snake."

"Yes, sir, Nolay, I'll look out for 'em."

Outside, the road was spotted with mud puddles full of minnows and tadpoles. Barefooted, I waded very gingerly through the brown water, just in case there was a snake laying around. The thirsty Florida sun had already begun to suck up huge amounts of precious water. As the puddles dried, the helpless little creatures were left to die a slow death in the heat.

I found the perfect spot and started building sand dams to reroute the water and trap the critters. Nippy ran happily from puddle to puddle and snatched up minnows and tadpoles. She would squat down on her haunches and with her little humanlike hands devour the critters like pieces of candy. I knew I couldn't interfere. Nolay had told me, "That's the way God set up nature; one day you're sittin' at the dinner table and the next day you might be on it."

Pearl dug a mudhole by some twisted palmetto roots and the dogs romped through the tangled scrub pines. I had nearly filled a whole Crisco can with squirmy things ready to be set loose in our big front pond, when I heard a gunshot ring out from the direction of our house.

I turned and ran as fast as I could back to the house. The dogs followed in hot pursuit. One of the dogs, Paddlefoot, smashed through my dams and sent cans and jars full of saved creatures wriggling out over the dry sand.

Breathlessly, I opened the door and stepped inside our living room. Mama stood on top of the couch, her little pearl-handled .32 revolver in her hand. Nolay was in front of her, a dead cottonmouth moccasin laying on the floor between them. He picked it up and held it by its tail. Part of the snake's body still curled on the floor; a trickle of blood flowed from its head and swirled out into the glossy brown water.

Nolay looked the body up and down and calmly said, "Well, I got to admit, that is a mighty big snake. Bigger than me, gotta be over six feet."

Mama stood still as a stone on the couch, the pistol pointed in the direction of the snake and Nolay.

Nolay said, "Honey Girl, you are one dead-eyed shot. Look at this, right through the head." He cleared his throat. "You might want to put that gun down. This snake cain't get no more deader than it is right now."

Mama moved her eyes from the snake to the gun; a look of puzzlement crossed her face. She slowly sat back down on the couch and placed the gun by her side.

Nolay glanced at me, then back to Mama. "I tell you what, Honey Girl, I'll go bring ol' Ikibob inside the house. I guarantee if there's any snakes left in here, he'll hunt 'em down. If there's one thing that ol' rooster don't like, it's a snake." He turned and walked out of the house, dragging the dead snake behind him. "Bones, you stay here with your mama."

I looked at Mama curled up on the couch. "Mama, if it's all right, I gotta get back outside. Paddlefoot knocked over all my cans and everything is out there drying up to death."

The sweltering month of July was gradually melting into August. Baby alligators were busy pecking their way out of their eggs when the biggest storm of the summer of 1949 blew into our lives. I was standing in the middle of our living room floor, cool brown water swirling over my feet and reaching nearly to the tops of my skinny ten-year-old ankles. The morning sun was just peeking in through our picture window, painting shiny rainbows across the water's dull surface.

My daddy, Nolay, paced slowly from one end of the room to the other. He was just as barefooted as me because there was no reason to be wearing shoes inside your house when it was full of water. Each small step sent ripples of coffee-colored water circling around the legs of what pieces of furniture we hadn't stacked on top of each other. Nolay solemnly raised his arms in the air and declared, "We live in the womb of the world! It's the womb of the world. Any fool can see it's God's womb of the world!"

Like a contented cat, Mama was curled up on the couch. I don't think she was really that contented, she just didn't have any choice but to sit there. Her slender arms wrapped around her legs and hugged them close to her body. Her head rested on her knees; only her eyes moved back and forth as she watched my daddy's every move.

Out of the corner of my eye I saw something dark and shiny slither along the side of the wall right behind the couch. I kept my mouth shut, because if there was one thing Mama didn't like, especially inside her house, it was snakes.

I was not quite sure what a womb was, but if Nolay said we lived in one, then it must be true. My daddy was about the smartest man I ever did know. I hadn't met very many men, but of the ones I had, he was about the smartest. He was a true man of vision.

He'd had the vision to nestle our house between a glorious Florida swamp and a long stretch of sandy scrub palmetto laced with majestic old pines. Although Mama often pointed out that his vision blurred when it came to the exact location. "If you had put this house a hundred yards closer to the county road we would have electricity. We would have a icebox and a sewing machine," Mama would say.

Nolay would shake his shaggy black curls and reply, "Lori, Honey Girl, you know I don't want to be any closer to that dang county road!"

Honey Girl was my daddy's nickname for Mama because her blond hair dripped down her back and around her shoulders like golden honey.

"If I could, I would have put us on a float right out in the middle of the swamp. But don't you fret, one day I'll buy my own durn electric poles and stick 'em in the ground myself."

But Mama couldn't deny that Nolay had had the vision to build our house on a strip of land at least a foot above water level. It only flooded when the heavy summer rains came. It really wasn't that bad; sometimes the water just seeped in and covered our floor with a fine, shiny mist.

Our house also had a flat tar-paper roof because, as Nolay had explained, "No matter how big a storm comes through, this roof will stay put. You go puttin' one of those pointed roofs on and sure as shootin' the first hurricane will take it off. Same thing goes for puttin' your house up on stilts." Yes, sir, Nolay was a true man of vision.

At any rate, all the excitement had started the day before. Me and Mama had just returned from a Saturday trip to town and were inside the house putting away groceries when Nolay called us.

"Honey Girl, Bones, y'all come on out here and take a look at this." He was standing in the yard looking east. That was where the Atlantic Ocean lived, and most of our storms came from that direction.

What I saw filled up the horizon. It looked like a massive black jellyfish. The cloud floated just above the ground and moved with fierce intent, heading directly toward us. The three of us stood like fence posts until Nolay said, "That's a mighty big storm coming our way. Y'all get the animals inside the house."

Me and Mama sprang to life, called the dogs, and looked for the cats. Half an hour later I made a final count: three dogs, five cats, one raccoon, one pig, and one goat, everyone accounted for. As I ran out the door I yelled over my shoulder, "Mama, I'm goin' out to help Nolay."

Nolay had just closed the door to the chicken coop. Old Ikibob Rooster sensed something was up and already had his brood cornered in one end of the coop. By the time we headed for the house, that jellyfish cloud was nearly on top of us. It hungrily gobbled up the silver-blue day and turned it into gloomy darkness.

As it hovered above us, it looked as if God reached his long pointy-finger down from heaven and ripped a huge gash in the stomach of that jellyfish. Gray sheets of water fell furiously to the ground. Cannonballs of thunder crashed and rolled angrily over the swamps. Like gigantic knives, silver streaks of lightning sliced through the darkness and stabbed the earth.

Me and all the animals were wide-eyed and looking for something to crawl under. Except for the flashes of lightning and the soft flicker of our kerosene lamps, our house was as black as the inside of a cow. I had never been inside a cow, but I imagined this was how totally dark it would be.

Our summer storms usually dumped a ton of water in the swamps. Water was precious to swamps; they needed it to stay alive. Sometimes a thin layer of water would run through our house, but this storm was big, and it was angry. The swamp quickly filled and began to leak out over its shallow edges. The little sliver of land our house sat on was soaked up like a dirty dishrag. Swamp water, along with some of its inhabitants, seeped under doorways and through cracks and crannies. Water came from every direction; it slid down the sides of our walls and dripped from the ceiling in endless streams.

Nolay began to bark out instructions. "Stack up them chairs, put a quilt on the table and get the cats up there, put the dogs in our bed, get the pig and goat into the washtub! Bones, do something with that dang crazy raccoon!"

When the three of us sat huddled together on the couch, Nolay murmured, "Don't worry about nothing, it's just a little water. It's just a storm, a big storm, but it's not a hurricane. The roof will stay on."

It was too wet and too dark for us to make it to a bedroom, so we decided it was best to just stay put right there on the couch. Nestled between the two of them, I fell asleep with the assurance that Nolay knew about hurricanes. The one in 1935 had blown his family home clear down to the ground. That house sat not ten feet away from the very spot we were at right now. About the only thing left was a pile of bricks where the chimney had stood, the artesian well that we still got our water from, and a mammoth mango tree.

On occasion, when things would get out of hand, like they were right now, Mama would look over to Nolay and say, "Why did you build our house next to one that blew down in a storm? You could have put us on higher ground."

But my daddy, with his vision and truthfulness, would reply, "Because this is where my home is and always will be. Don't worry, Honey Girl, I guarantee this house ain't gonna blow down."

Nolay's real name was Seminole, but no one ever called him that. His daddy, who was Miccosukee Indian, named him in honor of their kindred tribe. Nolay lived up to the true meaning of his name, which was "runaway; wild one."

All night long that storm pounded us with huge fists of water. At the break of dawn, as we waded through our living room, the first words out of Nolay's mouth were "Well, am I right or am I right? I said the dang roof would stay on, and it did!"

Nolay was right about the roof staying on, and it wouldn't be a concern any longer. Our real troubles would be coming all too soon.

Saving the Day

Mama refused to get off the couch, even after Nolay offered her a piggyback ride. She hugged her legs close to her body and kept her chin on her knees. She was not about to stick her feet in that dirty brown water. Just as Mama turned her head sideways, a little black snake wriggled along the side of the wall. She pointed and said, "My goodness, what is that? Is that a snake inside our house?"

I quickly waded over to it. "It's only a baby. It's scared and it's just trying to find its way back outside."

Mama groaned. "And I want it to go back outside." She looked at Nolay. "What else has the womb of the world dumped inside our house?"

"Lori, that's just a little ol' baby, it squeezed in through a crack. Don't worry; they ain't nothing in here but some harmless water."

I crept behind the couch and gingerly picked the snake up by its slippery little tail. I turned to Mama and said, "Look, Mama, it ain't much bigger than a fat old fishin' worm. It's probably one of Old Blackie's babies. I'll just take it outside where it belongs." Blackie was our resident blacksnake. She lived in the giant mango tree in our backyard.

Armed with Crisco cans and mason jars, I was ready to go outside and catch the bounty of tadpoles, minnows, and whatever else the swamp had spilled out on our driveway. Or what we called our driveway; it was actually a two-rut dirt road with ditches cut in on both sides. After every big summer rain I took it on myself to go out and catch as many living things as I could and dump them into the pond in our front yard. Of course, a fair amount of the creatures I would be picking up that day came from the pond in our front yard, but I felt it was my duty to save as many as I could.

With a great display of authority I dropped the pathetic little snake in my Crisco can and made my way to the front door. I whistled, and our three dogs, Nippy the raccoon, and Pearl the pig almost knocked me down as they clambered toward the door. Harry the goat had made himself quite comfortable in the washtub, his head hung over the rim and his big glassy eyes looking forlornly in my direction.

I strapped my trusty Roy Rogers cap pistols around my waist and opened the front door. I was getting too old to still be playing with cap pistols, but they just felt like a couple of friends hanging out with me. Nolay called out, "Bones, you watch out for snakes. Take a hoe or machete with you. They bound to be lookin' for dry land. And keep your eye on those dang dogs; the fools will stick their nose right on top of a snake."

"Yes, sir, Nolay, I'll look out for 'em."

Outside, the road was spotted with mud puddles full of minnows and tadpoles. Barefooted, I waded very gingerly through the brown water, just in case there was a snake laying around. The thirsty Florida sun had already begun to suck up huge amounts of precious water. As the puddles dried, the helpless little creatures were left to die a slow death in the heat.

I found the perfect spot and started building sand dams to reroute the water and trap the critters. Nippy ran happily from puddle to puddle and snatched up minnows and tadpoles. She would squat down on her haunches and with her little humanlike hands devour the critters like pieces of candy. I knew I couldn't interfere. Nolay had told me, "That's the way God set up nature; one day you're sittin' at the dinner table and the next day you might be on it."

Pearl dug a mudhole by some twisted palmetto roots and the dogs romped through the tangled scrub pines. I had nearly filled a whole Crisco can with squirmy things ready to be set loose in our big front pond, when I heard a gunshot ring out from the direction of our house.

I turned and ran as fast as I could back to the house. The dogs followed in hot pursuit. One of the dogs, Paddlefoot, smashed through my dams and sent cans and jars full of saved creatures wriggling out over the dry sand.

Breathlessly, I opened the door and stepped inside our living room. Mama stood on top of the couch, her little pearl-handled .32 revolver in her hand. Nolay was in front of her, a dead cottonmouth moccasin laying on the floor between them. He picked it up and held it by its tail. Part of the snake's body still curled on the floor; a trickle of blood flowed from its head and swirled out into the glossy brown water.

Nolay looked the body up and down and calmly said, "Well, I got to admit, that is a mighty big snake. Bigger than me, gotta be over six feet."

Mama stood still as a stone on the couch, the pistol pointed in the direction of the snake and Nolay.

Nolay said, "Honey Girl, you are one dead-eyed shot. Look at this, right through the head." He cleared his throat. "You might want to put that gun down. This snake cain't get no more deader than it is right now."

Mama moved her eyes from the snake to the gun; a look of puzzlement crossed her face. She slowly sat back down on the couch and placed the gun by her side.

Nolay glanced at me, then back to Mama. "I tell you what, Honey Girl, I'll go bring ol' Ikibob inside the house. I guarantee if there's any snakes left in here, he'll hunt 'em down. If there's one thing that ol' rooster don't like, it's a snake." He turned and walked out of the house, dragging the dead snake behind him. "Bones, you stay here with your mama."

I looked at Mama curled up on the couch. "Mama, if it's all right, I gotta get back outside. Paddlefoot knocked over all my cans and everything is out there drying up to death."