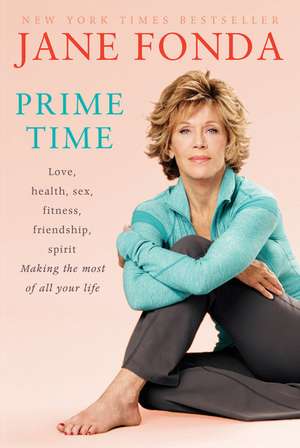

Prime Time: Making the Most of All of Your Life

Autor Jane Fondaen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2012

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Audies (2012)

An A-to-Z guide to living and aging well by #1 bestselling author, actress, and workout pioneer Jane Fonda

In this unique, candid, and inspiring book, Jane Fonda explores how midlife and beyond can be the time when we become our most energetic, loving, and fulfilled selves. Highlighting new research and sharing stories from her own life and from the lives of others, she outlines the 11 key ingredients to vitality—from exercise and diet, to forging new pathways in the brain, to loving, staying connected, and giving of oneself. She explains how performing a life review helped her clarify goals and move ahead, and shows how we can do this too. In Prime Time, Jane Fonda offers an empowering vision for how to live your best life, for all of your life.

Preț: 122.68 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 184

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.48€ • 25.52$ • 19.74£

23.48€ • 25.52$ • 19.74£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812978582

ISBN-10: 0812978587

Pagini: 416

Ilustrații: PHOTOS, ILLUSTRATIONS

Dimensiuni: 161 x 232 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.61 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0812978587

Pagini: 416

Ilustrații: PHOTOS, ILLUSTRATIONS

Dimensiuni: 161 x 232 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.61 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

Jane Fonda is an Oscar- and Emmy-winning actress and highly successful producer. She revolutionized the fitness industry with the Jane Fonda Workout in 1982 and has sold more than seventeen million copies of her fitness-focused books, videos, and recordings. She is involved with several causes and is the founder of both the Georgia Campaign for Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention and the Jane Fonda Center at Emory University. She is the author of the #1 New York Times bestseller My Life So Far, and she received a Tony nomination in 2009 for her role in 33 Variations. She lives in Los Angeles.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

PREFACE

The Arch and the Staircase

The past empowers the present, and the groping

footsteps leading to this present mark the pathways

to the future.

—Mary Catherine Bateson

Several years ago, i was coming to the end of my sixties

and facing my seventies, the second decade of what I thought of as

the Third Act of my life— Act III, which, as I see it, begins at age

sixty. I was worried. Being in my sixties was one thing. Given good

health, we can fudge our sixties. But seventy—now, that’s serious.

In our grandparents’ time, people in their seventies were considered

part of the “old old” . . . on their way out.

However, a revolution has occurred within the last century—

a longevity revolution. Studies show that, on average, thirty- four

years have been added to human life expectancy, moving it from an

average of forty- six years to eighty! This addition represents an

entire second adult lifetime, and whether we choose to confront it

or not, it changes everything, including what it means to be human.

Adding a Room

The social anthropologist (and a friend of mine) Mary Catherine

Bateson has a metaphor for living with this longer life span in view.

She writes in her recent book Composing a Further Life: The Age of Active

Wisdom, “We have not added decades to life expectancy by simply

extending old age; instead, we have opened up a new space partway

through the life course, a second and different kind of adulthood

that precedes old age, and as a result every stage of life is undergoing

change.” Bateson uses the identifi able metaphor of what happens

when a new room is added to your home. It isn’t just the new

room that is different; every other part of the house and how it is

used is altered a bit by the addition of this room.

In the house that is our life, things such as planning, marriage,

love, fi nances, parenting, travel, education, physical fi tness, work,

retirement—our very identities, even!—all take on new meaning

now that we can expect to be vital into our eighties and nineties

. . . or longer.

But our culture has not come to grips with the ways the longevity

revolution has altered our lives. Institutionally, so much of how

we do things is the same as it was early in the twentieth century,

with our lives segregated into age- specifi c silos: During the fi rst

third we learn, during the second third we produce, and the last

third we presumably spend on leisure. Consider, instead, how it

would look if we tore down the silos and integrated the activities.

For example, let’s begin to think of learning and working as a lifelong

challenge instead of something that ends when you retire.

What if the wonderfully empowering feeling of being productive

can be experienced by children early in life, and if they know from

fi rst grade that education will be an expected part of their entire

lives? What if the second, traditionally productive silo is braided

with leisure and education? And seniors, with twenty or more productive

years left, can enjoy leisure time while remaining in the

workforce in some form and attending to education if for no other

reason than to challenge their minds? Envisioned this way, longevity

becomes like a symphony with echoes of different times recurring

with slight modifi cations, as in music, across the life arc.

Except that we don’t have the sheet music to this new symphony.

We— today’s boomers and seniors— are the pioneer generations,

the ones who need to compose together a template for how

to maximize the potential of this amazing gift of time, so as to

become whole, fully realized people over the longer life arc.

In attempting to chart a course for myself into my sixties and

beyond, I’ve found it helpful to view the symphony of my own life

in three acts, or three major developmental stages: Act I, the fi rst

three decades; Act II, the middle three decades; and Act III, the

fi nal three decades (or however many more years one is granted).

As I searched for ways to understand the new realities of aging,

I discovered the arch and the staircase.

The Arch and the Staircase

Here you see two diagrams that I have had drawn, because they

make visualizable two conceptions of human life that have come to

mean a lot to me.

One diagram, the arch, represents a biological concept, taking

us from childhood to a middle peak of maturity, followed by a

decline into infi rmity.

The other, a staircase, shows our potential for upward progression

toward wisdom, spiritual growth, learning— toward, in other

words, consciousness and soul.

The vision behind these diagrams was developed by Rudolf Arnheim,

the late professor emeritus of the psychology of art at Harvard

University, and for me they are clear metaphors for ways we can choose

to view aging. Our youth- obsessed culture encourages us to focus

on the arch—age as physical decline— more than on the stairway— age

as potential for continued development and ascent. But it is the stairway

that points to late life’s promise, even in the face of physical

decline. Perhaps it should be a spiral staircase! Because the wisdom,

balance, refl ection, and compassion that this upward movement represents

don’t just come to us in one linear ascension; they circle around

us, beckoning us to keep climbing, to keep looking both back and

ahead.

Rehearsing the Future

Throughout my life, whenever I was confronted by something I

feared, I tried to make it my best friend, stare it in the face, and get

to know its ins and outs. Eleanor Roosevelt once said, “You gain

strength, courage, and confi dence by every experience in which you

really stop to look fear in the face.” I have found this to be true.

This is how I discovered that knowledge about what lies ahead can

empower me, help me conquer my fears, take the wind out of the

sails of my anxiety. Know thine enemy! Remember Rumpelstiltskin,

the evil dwarf in the Grimms’ fairy tale? He was destroyed

once the miller’s daughter learned his name and called it out. When

we name our fears, bring them out into the open, and examine

them in the light, they weaken and wither.

So, one of the ways I have tried to overcome my fears of aging

involved rehearsing for it. In fact, I started doing this in Act II. I

believe that this rehearsal for the future (along with doing a life

review of the past) is part of why I have been able— so far— to live

Act III with relative equanimity.

Being with my father when he was in his late seventies and in

decline due to heart problems was what began to shatter any childhood

illusions I’d had of immortality. I was in my mid- forties, and it

hit me that with him gone, I would be the oldest one left in the family

and, before too long, next at the turnstile. I realized then that it was

not so much the idea of death itself that frightened me as it was being

faced with regrets, the “what if”s and the “if only”s when there is no

time left to do anything about them. I didn’t want to arrive at the end

of the Third Act and discover too late all that I had not done.

I began to feel the need to project myself into the future, to

visualize who I wanted to be and what regrets I might have that I

would need to address before I got too old. I wanted to understand

as much as possible what cards age would deal me; what I could

realistically expect of myself physically; how much of aging was

negotiable; and what I needed to do to intervene on my own behalf

with what appeared to be a downward slope.

The birth of my two children had taught me the importance of

knowledge and preparation. The fi rst birth had been a terrifying,

lonely experience; I went through it unprepared and unrehearsed,

swept along passively in a sea of pain. The second birth was quite

the opposite. My husband and I worked with a birth educator in

the months leading up to my due date, so that I was able to visualize

what would happen and know what to do. The physical ordeal

was no less grueling, the process no faster, but the experience itself

was transformed. With knowledge and rehearsal, I found it easier

to ride atop the sequence of events rather than be totally submerged

by the pain.

I brought what I’d learned from childbirth to my experience

facing late midlife. As I said, I was scared back then— it is hard to

let go of children, of the success that came with youth, of old identities

when new ones aren’t yet clearly defi ned. I felt I could choose

whether to be blindly propelled into later life, in denial with my

eyes wide shut, or I could take charge and seek out what I needed

to know in order to make informed decisions in the many changing

areas of my life. That’s why, in 1984, at age forty- six, before I’d even

had my fi rst hot fl ash, I wrote Women Coming of Age, with Mignon

McCarthy, about what women can expect, physically, as they age,

and what parts of aging are negotiable. It was a way to force myself

to confront and rehearse the future. I was shocked to discover how

little research had been devoted to women’s health. Most medical

studies I found had been done on men. I’m happy to say this has

started to change.

At forty- six, I began to envision the old woman I wished to be,

and I described her in that book:

I see an old woman walking briskly, out- of- doors, in every

season. She’s feisty. She’s not afraid of being alone. Her face

is lined and full of life. There’s a ruddy fl ush to her cheeks

and a bright curious look in her eye because she’s still learning.

Her husband often walks with her. They laugh a lot. She

likes to be with young people and she’s a good listener. Her

grandchildren love to tell her stories and to hear hers because

she’s got some really good ones that contain sweet, hidden

lessons about life. She has a conscious set of values and the

knack to make them compelling to her young friends.

This is an example of rehearsing the future . . . good to do at any age!

I’m glad I wrote it down, because it’s fun for me to read my

forty- six- year- old vision of my senior self, almost thirty years later, as

a reality check to see how well I’m doing. Some days, I actually think

I’m doing pretty well. I’m still feisty, and my solitude (which I cherish)

doesn’t feel like loneliness. Humor has defi nitely come to the

fore. I’m no longer married, but I do walk together with my— what

to call the man I am with when I’m seventy- two and unmarried?

“Boyfriend” sounds too juvenile, don’t you think? So then, what?

“Lover?” That seems too in- your- face. I think I’ll go with “honey.”

Anyway, my honey and I walk together, we laugh a lot, and we try to

swing- dance for fi fteen or twenty minutes every night— when we

can. I feel I may have fi nally conquered my diffi culties with intimacy.

(Or maybe I just found a man who isn’t scared of it!)

Gerontologists such as Bernice Neugarten have learned from

their studies of the aged that traumatic events— widowhood,

menopause, loss of a job, even imminent death— are not experienced

as traumas “if they were anticipated and, in effect, rehearsed as

part of the life cycle.”

Betty Friedan, in her book The Fountain of Age, wrote, “The fi nding

emerges that the difference between knowing and planning,

and not knowing what to expect (or denial of change because of

false expectations) can be the crucial factor between moving on to

new growth in the last third of life, or succumbing to stagnation,

pathology, and despair.”

With the help of many friends of all ages, as well as gerontologists,

sexologists, urologists, biologists, psychologists, experts in

cognitive research and health care, and a physicist or two, I have

written this book. Even though I was already in my own Act III,

doing this has been a form of rehearsal— for myself and for you, the

reader. I wanted to be prepared and learn all I could. I wanted to

be able to say to myself and to you, “Let’s make the most of the

years that take us from midlife to the end, and here’s how!”

I do not want to romanticize the process of aging. Obviously,

there is no guarantee that this will be a time of growth and fruition.

There are negatives to any stage of life, including potentially serious

issues of mental and physical health. I cannot address all these

things within the scope of this book. As we know, some of how life

unfolds is a matter of luck. Some of it—about one- third, actually—

is genetic and beyond our control. The good news is that this means

that for a lot of it, maybe two- thirds of the life arc, we can do something

about how well we do.

This book is for those of us who, like me, believe that luck is

opportunity meeting preparation; that with preparation and knowledge,

with information and refl ection, we can try to raise the odds

of being lucky, and of making our last three decades— our Third

Acts— the most peaceful, generous, loving, sensual, transcendent

time of all; and that planning for it, especially during one’s middle

years, can help make this so.

Wholeness

Arnheim’s staircase made me realize how important it can be to see

life as an interplay between one’s beginning, middle, and end. I

found out that if we understand more deeply what Act I and Act II

are (or were) about, who we are (or were becoming) during those

foundational years, what dreams are still to be realized and which

regrets addressed, then we can see Act III as a coming to fruition,

rather than simply a period of marking time, or the absence of

youth. We can understand it not as the far side of the arch— as the

decline after the peak— but as a stage of development in its own terms.

We can experience it as part of the staircase— with its own challenges

and joys, pitfalls and rewards, a stage as evolving and as satisfying

and different from midlife or youth as adolescence is from

childhood.

In 1996, Erik and Joan Erikson wrote, in The Life Cycle Completed,

“Lacking a culturally viable ideal of old age, our civilization does

not really harbor a concept of the whole of life.”4 The old ways of

thinking about age, the fears of losing our youth and facing our

own mortality, have kept us from seeing Act III as a vital, inte-

grated part of our overall story, the potential- fi lled culmination of

the fi rst two acts. This old thinking is even more tragic now, in light

of the extension of the life span. It can rob us of wholeness, and it

can rob society of what we each, in our ripeness, have to offer.

Those of us now entering our Third Acts are, on the whole,

physically stronger and healthier than ever before. There is every

likelihood that, if we work at it individually and collectively, we can

develop a new “culturally viable ideal of old age” and see our lives as

a series of stages that build one upon the other. Our doing so will

not be just for us; it will represent a major cultural shift for the

world around us and will help younger generations reconceive of

their own life spans.

I have been inspired and encouraged by what I have learned

while writing this book. I hope reading it will do the same for you.

And so let’s begin.

From the Hardcover edition.

The Arch and the Staircase

The past empowers the present, and the groping

footsteps leading to this present mark the pathways

to the future.

—Mary Catherine Bateson

Several years ago, i was coming to the end of my sixties

and facing my seventies, the second decade of what I thought of as

the Third Act of my life— Act III, which, as I see it, begins at age

sixty. I was worried. Being in my sixties was one thing. Given good

health, we can fudge our sixties. But seventy—now, that’s serious.

In our grandparents’ time, people in their seventies were considered

part of the “old old” . . . on their way out.

However, a revolution has occurred within the last century—

a longevity revolution. Studies show that, on average, thirty- four

years have been added to human life expectancy, moving it from an

average of forty- six years to eighty! This addition represents an

entire second adult lifetime, and whether we choose to confront it

or not, it changes everything, including what it means to be human.

Adding a Room

The social anthropologist (and a friend of mine) Mary Catherine

Bateson has a metaphor for living with this longer life span in view.

She writes in her recent book Composing a Further Life: The Age of Active

Wisdom, “We have not added decades to life expectancy by simply

extending old age; instead, we have opened up a new space partway

through the life course, a second and different kind of adulthood

that precedes old age, and as a result every stage of life is undergoing

change.” Bateson uses the identifi able metaphor of what happens

when a new room is added to your home. It isn’t just the new

room that is different; every other part of the house and how it is

used is altered a bit by the addition of this room.

In the house that is our life, things such as planning, marriage,

love, fi nances, parenting, travel, education, physical fi tness, work,

retirement—our very identities, even!—all take on new meaning

now that we can expect to be vital into our eighties and nineties

. . . or longer.

But our culture has not come to grips with the ways the longevity

revolution has altered our lives. Institutionally, so much of how

we do things is the same as it was early in the twentieth century,

with our lives segregated into age- specifi c silos: During the fi rst

third we learn, during the second third we produce, and the last

third we presumably spend on leisure. Consider, instead, how it

would look if we tore down the silos and integrated the activities.

For example, let’s begin to think of learning and working as a lifelong

challenge instead of something that ends when you retire.

What if the wonderfully empowering feeling of being productive

can be experienced by children early in life, and if they know from

fi rst grade that education will be an expected part of their entire

lives? What if the second, traditionally productive silo is braided

with leisure and education? And seniors, with twenty or more productive

years left, can enjoy leisure time while remaining in the

workforce in some form and attending to education if for no other

reason than to challenge their minds? Envisioned this way, longevity

becomes like a symphony with echoes of different times recurring

with slight modifi cations, as in music, across the life arc.

Except that we don’t have the sheet music to this new symphony.

We— today’s boomers and seniors— are the pioneer generations,

the ones who need to compose together a template for how

to maximize the potential of this amazing gift of time, so as to

become whole, fully realized people over the longer life arc.

In attempting to chart a course for myself into my sixties and

beyond, I’ve found it helpful to view the symphony of my own life

in three acts, or three major developmental stages: Act I, the fi rst

three decades; Act II, the middle three decades; and Act III, the

fi nal three decades (or however many more years one is granted).

As I searched for ways to understand the new realities of aging,

I discovered the arch and the staircase.

The Arch and the Staircase

Here you see two diagrams that I have had drawn, because they

make visualizable two conceptions of human life that have come to

mean a lot to me.

One diagram, the arch, represents a biological concept, taking

us from childhood to a middle peak of maturity, followed by a

decline into infi rmity.

The other, a staircase, shows our potential for upward progression

toward wisdom, spiritual growth, learning— toward, in other

words, consciousness and soul.

The vision behind these diagrams was developed by Rudolf Arnheim,

the late professor emeritus of the psychology of art at Harvard

University, and for me they are clear metaphors for ways we can choose

to view aging. Our youth- obsessed culture encourages us to focus

on the arch—age as physical decline— more than on the stairway— age

as potential for continued development and ascent. But it is the stairway

that points to late life’s promise, even in the face of physical

decline. Perhaps it should be a spiral staircase! Because the wisdom,

balance, refl ection, and compassion that this upward movement represents

don’t just come to us in one linear ascension; they circle around

us, beckoning us to keep climbing, to keep looking both back and

ahead.

Rehearsing the Future

Throughout my life, whenever I was confronted by something I

feared, I tried to make it my best friend, stare it in the face, and get

to know its ins and outs. Eleanor Roosevelt once said, “You gain

strength, courage, and confi dence by every experience in which you

really stop to look fear in the face.” I have found this to be true.

This is how I discovered that knowledge about what lies ahead can

empower me, help me conquer my fears, take the wind out of the

sails of my anxiety. Know thine enemy! Remember Rumpelstiltskin,

the evil dwarf in the Grimms’ fairy tale? He was destroyed

once the miller’s daughter learned his name and called it out. When

we name our fears, bring them out into the open, and examine

them in the light, they weaken and wither.

So, one of the ways I have tried to overcome my fears of aging

involved rehearsing for it. In fact, I started doing this in Act II. I

believe that this rehearsal for the future (along with doing a life

review of the past) is part of why I have been able— so far— to live

Act III with relative equanimity.

Being with my father when he was in his late seventies and in

decline due to heart problems was what began to shatter any childhood

illusions I’d had of immortality. I was in my mid- forties, and it

hit me that with him gone, I would be the oldest one left in the family

and, before too long, next at the turnstile. I realized then that it was

not so much the idea of death itself that frightened me as it was being

faced with regrets, the “what if”s and the “if only”s when there is no

time left to do anything about them. I didn’t want to arrive at the end

of the Third Act and discover too late all that I had not done.

I began to feel the need to project myself into the future, to

visualize who I wanted to be and what regrets I might have that I

would need to address before I got too old. I wanted to understand

as much as possible what cards age would deal me; what I could

realistically expect of myself physically; how much of aging was

negotiable; and what I needed to do to intervene on my own behalf

with what appeared to be a downward slope.

The birth of my two children had taught me the importance of

knowledge and preparation. The fi rst birth had been a terrifying,

lonely experience; I went through it unprepared and unrehearsed,

swept along passively in a sea of pain. The second birth was quite

the opposite. My husband and I worked with a birth educator in

the months leading up to my due date, so that I was able to visualize

what would happen and know what to do. The physical ordeal

was no less grueling, the process no faster, but the experience itself

was transformed. With knowledge and rehearsal, I found it easier

to ride atop the sequence of events rather than be totally submerged

by the pain.

I brought what I’d learned from childbirth to my experience

facing late midlife. As I said, I was scared back then— it is hard to

let go of children, of the success that came with youth, of old identities

when new ones aren’t yet clearly defi ned. I felt I could choose

whether to be blindly propelled into later life, in denial with my

eyes wide shut, or I could take charge and seek out what I needed

to know in order to make informed decisions in the many changing

areas of my life. That’s why, in 1984, at age forty- six, before I’d even

had my fi rst hot fl ash, I wrote Women Coming of Age, with Mignon

McCarthy, about what women can expect, physically, as they age,

and what parts of aging are negotiable. It was a way to force myself

to confront and rehearse the future. I was shocked to discover how

little research had been devoted to women’s health. Most medical

studies I found had been done on men. I’m happy to say this has

started to change.

At forty- six, I began to envision the old woman I wished to be,

and I described her in that book:

I see an old woman walking briskly, out- of- doors, in every

season. She’s feisty. She’s not afraid of being alone. Her face

is lined and full of life. There’s a ruddy fl ush to her cheeks

and a bright curious look in her eye because she’s still learning.

Her husband often walks with her. They laugh a lot. She

likes to be with young people and she’s a good listener. Her

grandchildren love to tell her stories and to hear hers because

she’s got some really good ones that contain sweet, hidden

lessons about life. She has a conscious set of values and the

knack to make them compelling to her young friends.

This is an example of rehearsing the future . . . good to do at any age!

I’m glad I wrote it down, because it’s fun for me to read my

forty- six- year- old vision of my senior self, almost thirty years later, as

a reality check to see how well I’m doing. Some days, I actually think

I’m doing pretty well. I’m still feisty, and my solitude (which I cherish)

doesn’t feel like loneliness. Humor has defi nitely come to the

fore. I’m no longer married, but I do walk together with my— what

to call the man I am with when I’m seventy- two and unmarried?

“Boyfriend” sounds too juvenile, don’t you think? So then, what?

“Lover?” That seems too in- your- face. I think I’ll go with “honey.”

Anyway, my honey and I walk together, we laugh a lot, and we try to

swing- dance for fi fteen or twenty minutes every night— when we

can. I feel I may have fi nally conquered my diffi culties with intimacy.

(Or maybe I just found a man who isn’t scared of it!)

Gerontologists such as Bernice Neugarten have learned from

their studies of the aged that traumatic events— widowhood,

menopause, loss of a job, even imminent death— are not experienced

as traumas “if they were anticipated and, in effect, rehearsed as

part of the life cycle.”

Betty Friedan, in her book The Fountain of Age, wrote, “The fi nding

emerges that the difference between knowing and planning,

and not knowing what to expect (or denial of change because of

false expectations) can be the crucial factor between moving on to

new growth in the last third of life, or succumbing to stagnation,

pathology, and despair.”

With the help of many friends of all ages, as well as gerontologists,

sexologists, urologists, biologists, psychologists, experts in

cognitive research and health care, and a physicist or two, I have

written this book. Even though I was already in my own Act III,

doing this has been a form of rehearsal— for myself and for you, the

reader. I wanted to be prepared and learn all I could. I wanted to

be able to say to myself and to you, “Let’s make the most of the

years that take us from midlife to the end, and here’s how!”

I do not want to romanticize the process of aging. Obviously,

there is no guarantee that this will be a time of growth and fruition.

There are negatives to any stage of life, including potentially serious

issues of mental and physical health. I cannot address all these

things within the scope of this book. As we know, some of how life

unfolds is a matter of luck. Some of it—about one- third, actually—

is genetic and beyond our control. The good news is that this means

that for a lot of it, maybe two- thirds of the life arc, we can do something

about how well we do.

This book is for those of us who, like me, believe that luck is

opportunity meeting preparation; that with preparation and knowledge,

with information and refl ection, we can try to raise the odds

of being lucky, and of making our last three decades— our Third

Acts— the most peaceful, generous, loving, sensual, transcendent

time of all; and that planning for it, especially during one’s middle

years, can help make this so.

Wholeness

Arnheim’s staircase made me realize how important it can be to see

life as an interplay between one’s beginning, middle, and end. I

found out that if we understand more deeply what Act I and Act II

are (or were) about, who we are (or were becoming) during those

foundational years, what dreams are still to be realized and which

regrets addressed, then we can see Act III as a coming to fruition,

rather than simply a period of marking time, or the absence of

youth. We can understand it not as the far side of the arch— as the

decline after the peak— but as a stage of development in its own terms.

We can experience it as part of the staircase— with its own challenges

and joys, pitfalls and rewards, a stage as evolving and as satisfying

and different from midlife or youth as adolescence is from

childhood.

In 1996, Erik and Joan Erikson wrote, in The Life Cycle Completed,

“Lacking a culturally viable ideal of old age, our civilization does

not really harbor a concept of the whole of life.”4 The old ways of

thinking about age, the fears of losing our youth and facing our

own mortality, have kept us from seeing Act III as a vital, inte-

grated part of our overall story, the potential- fi lled culmination of

the fi rst two acts. This old thinking is even more tragic now, in light

of the extension of the life span. It can rob us of wholeness, and it

can rob society of what we each, in our ripeness, have to offer.

Those of us now entering our Third Acts are, on the whole,

physically stronger and healthier than ever before. There is every

likelihood that, if we work at it individually and collectively, we can

develop a new “culturally viable ideal of old age” and see our lives as

a series of stages that build one upon the other. Our doing so will

not be just for us; it will represent a major cultural shift for the

world around us and will help younger generations reconceive of

their own life spans.

I have been inspired and encouraged by what I have learned

while writing this book. I hope reading it will do the same for you.

And so let’s begin.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Reassuring . . . upbeat . . . Prime Time is part autobiographical confessional, part life advice, the two intertwined, so that reading the book is often like talking to a friend.”—Los Angeles Times

“A how-to book about being happy and self-aware [that] cites research and interviews with upbeat, lively, sexually active older people to extract some all-purpose lessons about endurance.”—The New York Times

“Warm, informative, and incredibly life affirming.”—Woman’s Day

“Read this, age gracefully.”—InStyle

“A how-to book about being happy and self-aware [that] cites research and interviews with upbeat, lively, sexually active older people to extract some all-purpose lessons about endurance.”—The New York Times

“Warm, informative, and incredibly life affirming.”—Woman’s Day

“Read this, age gracefully.”—InStyle

Descriere

Descriere de la o altă ediție sau format:

Covering the 11 key ingredients for vital living, Fonda shows you how to enjoy a more insightful, healthy and fully integrated life - one that is profoundly in touch with yourself, your body, mind and spirit, and with your talents, friends and community.

Covering the 11 key ingredients for vital living, Fonda shows you how to enjoy a more insightful, healthy and fully integrated life - one that is profoundly in touch with yourself, your body, mind and spirit, and with your talents, friends and community.

Premii

- Audies Winner, 2012