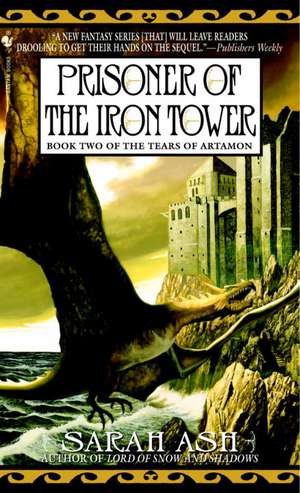

Prisoner of the Iron Tower: Book Two of the Tears of Artamon: Tears of Artamon (Paperback), cartea 02

Autor Sarah Ashen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2005 – vârsta de la 14 ani

Gavril Nagarian has finally cast out the dragon-daemon from deep within himself. The Drakhaoul is gone—and with it all of Gavril’s fearsome powers. Though no longer besieged by the Drakhaoul’s unnatural lusts and desires, Gavril has betrayed his birthright and his people. He has put the ice-bound princedom of Azhkendir at risk and lost.

Emerging from his battle with the Lord Drakhaon scarred but victorious, Eugene of Tielen exacts a terrible price. He arrests the renegade warlord Gavril Nagarian for crimes against the Rossiyan Empire and sentences him to life in an insane asylum—for the absence of the Drakhaoul is slowly driving Gavril mad. But Eugene has another motive as well. He longs to possess the Drakhaoul—at any cost to his kingdom and his humanity. With Gavril locked inside the Iron Tower, three women keep his memory alive. His mother returns to the warmer climes of her homeland, where she foments the seeds of rebellion. A young scullery maid whose heart is broken by Gavril’s arrest sends her spirit out to the Ways Beyond. And even the emperor’s new wife is haunted by her remembrances of the handsome young painter who once captured her soul.

The five princedoms of a shattered empire are reunited. The last of Artamon’s ruby tears adorns Eugene’s crown. But peace is as fragile as a rebel’s whisper—and a captive’s wish to be free.

Glowing with the powers of light and darkness, Prisoner of the Iron Tower will astonish and enthrall you, as courtly intrigue collides with the fantastic—and good and evil become as nebulous as the outlines of a dream.

Preț: 55.23 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 83

Preț estimativ în valută:

10.57€ • 11.02$ • 8.78£

10.57€ • 11.02$ • 8.78£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553586220

ISBN-10: 055358622X

Pagini: 576

Dimensiuni: 110 x 170 x 31 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Ediția:Bantam Mass Mar.

Editura: Spectra Books

Seria Tears of Artamon (Paperback)

ISBN-10: 055358622X

Pagini: 576

Dimensiuni: 110 x 170 x 31 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Ediția:Bantam Mass Mar.

Editura: Spectra Books

Seria Tears of Artamon (Paperback)

Notă biografică

Sarah Ash is the author of six fantasy novels: Children of the Serpent Gate, Lord of Snow and Shadows, Prisoner of the Iron Tower, Moths to a Flame, Songspinners, and The Lost Child. She also runs the library in a local primary school. Ash has two grown sons and lives in Beckenham, Kent, with her husband and their mad cat, Molly.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

PRISONER OF THE IRON TOWER

Chapter 1

W Astasia Orlova leaned on the rail of the Tielen ship that was carrying her back home to Muscobar across the Straits. Cold seaspray blew into her face, her hair, but she did not care.

She was bearing Count Velemir’s ashes back to Mirom. It was Feodor Velemir who had brought her to Tielen on the pretense that wreckage from her brother Andrei’s command, the Sirin, had been washed up on the shore. She had gone, eager that there might be the faintest glimmer of hope that Andrei was not drowned but lying injured in some remote fisherman’s hut, only to find that it had all been a ruse to display her charms to the Tielen court and council, to persuade them that she would make a suitable bride for Prince Eugene.

Well, Count, she thought, gazing into the rolling sea mist that hid the coastline of Muscobar from view, you have paid the ultimate price for your treachery. You used me heartlessly. You lied, you twisted the truth to further your own ends, and now you are dead.

But even now she was not sure she believed the evidence of her own eyes. What she had witnessed in the snowy palace yard had shaken her to the very core.

There crouched a dark-winged creature, veiled in a blue shimmer of heat. And—most horrible of all—the burning remains of something that had once been Feodor Velemir, Muscobar’s ambassador to Tielen, lay in a charred, smoking heap at its feet.

Drakhaon.

In that one moment all certainties had been seared away.

“Altessa!” Nadezhda, her maid, came up to her, carrying a wool shawl. “You’ll catch a chill up here in this bitter wind.”

“Don’t fuss, Nadezhda. I’m fine.”

Nadezhda took no notice and draped the shawl over Astasia’s shoulders. “Please come below and warm yourself.”

“Not yet,” Astasia said distantly. “In a while . . .”

The cloudy sky and the choppy sea mirrored her mood. She felt numbed. Whenever she tried to sleep, she saw the Drakhaon of Azhkendir rear up out of the darkness and then, oh then—

The one moment she could not forget, the moment when the dragon-winged daemon had turned its piercing blue gaze on her and she had recognized Gavril Andar.

Elysia Andar had tried to warn her, but she had refused to listen. Yet now she knew it to be true. Gavril, the one man she had ever allowed to hold her, to kiss her, was possessed by a dragon-daemon—

“Altessa.”

She turned to see that one of the Tielen officers had come up on deck.

“We have received an urgent message from Mirom, altessa, that concerns you. Will you please come below?”

Reluctantly, Astasia followed him belowdecks to the captain’s anteroom. Chancellor Maltheus had sent an escort of the household guard to protect her . . . or to prevent her from running away?

A group of officers were gathered around the table; they bowed as she entered.

“Is there a storm coming?” she asked, taking off the shawl. The fine mist of seaspray still clung to her hair. “Should we seek harbor and sit it out?”

“The message comes from Field Marshal Karonen, altessa. He reports there is rioting in Mirom. It seems that your parents have been trapped in the Winter Palace by a mob of dissidents who are threatening to torch the palace and all inside.”

Astasia gripped the edge of the table to steady herself. “Dissidents?” she repeated.

“Your father has requested our help. It seems the situation is quite desperate.”

“My father is asking for help?” Astasia said. If nothing else, this brought home the severity of the situation. Her father never asked for help.

“The Field Marshal is ready to lead a rescue force into the city, altessa. Just give the word and he will liberate the palace.”

Astasia gazed warily around at all the Tielen officers. She could not help noticing the detailed map of Mirom that lay outspread on the table. They seemed so well-prepared. . . .

“We understand there has been unrest in the city for some months,” said one.

“Well, yes—” she began, then broke off. How could she have been so blind? Maltheus had sent the soldiers with her as part of the invasion force. What better way to infiltrate Tielen soldiers into the heart of the city? Dissidents or no, Muscobar was about to be swallowed up into the growing Tielen empire.

“Prince Eugene is determined to quell any last stirrings of rebellion before your wedding takes place.”

“Of course,” she said coldly. They were still looking at her expectantly, and she realized that they were waiting for her command.

“Tell the Field Marshal,” she said, knowing she had no choice, “to put down the rebellion—and with my blessing.”

Astasia struggled up on deck against the prevailing wind, into a raw, red dawn. As the ship sailed up the broad Nieva, she noticed that the gilded dome of the Senate House had been reduced to a smoldering shell. And while at first she had believed the red glare in the sky to be the rising sun, surely no dawn could glow that brightly?

No, the West Wing of the palace was on fire.

She heard the crackle of the flames, the tinkle of breaking glass as panes burst in the heat; she saw the haze of smoke sullying the freshness of the dawn.

They were burning her home.

“No!” she cried aloud, gripping the rail to steady herself.

Now she could hear shouts from the shore; a confusion of people was swarming over the neatly clipped boxes and yews. Guards leaned from the windows, aiming muskets at the rabble, firing. A ragged rat-a-tat of fusillades answered.

“You must go belowdecks, altessa!” One of the Tielen officers came toward her, pistol in hand. “It’s not safe up here!”

Screams carried on the wind, shrill above the rattle of gunfire. There were running silhouettes at the West Wing windows, dark against the blaze of the flames. Where were Mama and Papa? Where was her governess, poor, dear Eupraxia? She would be so flustered by the panic and the fire—

“There are people trapped in there!” she said to the officer, grabbing his arm and stabbing her finger at the burning building. “We must get them out!”

A musket ball whizzed over their heads, grazing the nearest mast, showering them with sharp splinters of wood.

“We’re doing all we can,” he said, hurrying her toward the hatch.

The battle for the Winter Palace lasted little more than an hour. Astasia crept back up on deck and watched as more and more Tielen soldiers swarmed into the gardens, driving the rebels before them, rounding them up at musket-point.

By now the West Wing was well-alight, and she saw looters risk- ing the Tielen guns to carry away brocade curtains, pictures, fine porcelain . . . Too late, some servants formed a bucket-chain while others water from the river. Flames burst through the roof. Rafters cracked and the whole structure collapsed inward with a crash like rolling thunder.

Shocked beyond speech, she stood with her hands clutched to her mouth. The clouds of acrid smoke carried the vile smell of burning: timber, molten glass, and, worst of all, human flesh.

“I’ve made some tea, altessa.” She had not noticed that Nadezhda had emerged from belowdecks. “You’ve eaten nothing for hours. You need to keep up your strength.”

“Mama,” Astasia whispered into the billowing smoke. “Papa . . .”

“Tea with a drop of brandy, that’ll warm you up.” Nadezhda took her by the arm and steered her back below.

At about four in the afternoon, a party of Muscobar officers came on board and asked to speak with her. Sick with worry, she hurried to meet them.

“Colonel Roskovski!” she cried, so glad to see a familiar face that she wanted to run up and hug him.

“Altessa,” he said, clicking his heels and saluting her. He looked haggard; he was unshaven and his immaculate white uniform jacket was covered in smears of soot. “Thank God you’re safe.”

“Is there . . . is there any news of my parents?”

“They are under the protection of Field Marshal Karonen,” he said stiffly.

“But they’re alive?”

“I believe so. Altessa—” he hesitated. “I have been obliged to surrender control of the city to the Field Marshal.” She saw now that not only was he exhausted, but there were tears in his smoke-reddened eyes—tears of humiliation and defeat. “I am dishonored. I have failed your father.”

“Not surrender, Colonel,” she said, dismayed that such a proud and experienced soldier should openly weep with shame in front of her. “I’m sure you and your men did everything you could to save the city. But the odds were overwhelming. Without Tielen’s help—”

“Altessa Astasia!” One of the Tielen officers came running up. “The Field Marshal requests a meeting.”

Her heart began to beat overfast, a butterfly trapped in her breast. This was to do with her parents, she was sure of it. How would she find them? Even if they were physically unharmed, the last few days would have taken a terrible toll on Mama’s nerves. And Papa . . .

“Colonel,” she said, “please accompany me.”

It seemed that there were Tielen soldiers everywhere: lining the quay as Astasia disembarked, guarding the Water Gate, and patrolling the outer walls where the rebels had smashed down the iron railings as they stormed the palace.

Even though the officers steered a carefully chosen path, Astasia saw soldiers carrying out bodies from the courtyards and piling them onto carts. Through an archway she glimpsed some of Roskovski’s men cutting down a palace guard who was hanging from a lamppost, his white uniform red with his own blood.

“Were many killed?” she asked, determined that she should not be treated like a child.

“Enough,” Roskovski said tersely.

She wanted to avert her gaze from the bodies, but found she could not look away. One bright head of hair, as fiery as a fox’s pelt, caught her eye. One of her mother’s maids, Biata, had hair of just that unusual shade. . . .

The woman’s head lolled at an unnatural angle over the edge of the cart, eyes fixed, staring out from a wax-pale face. A trickle of blood from both nostrils darkened her lips, her chin.

“Biata?” But what point was there in calling her name when she was beyond hearing? And even as Astasia watched, the Tielens unceremoniously flung another body onto the cart, right on top of her. They were not distinguishing rioters from palace servants, they were just clearing away corpses.

Astasia started forward, outraged, and felt a firm touch on her shoulder.

“These men mean no disrespect,” said Roskovski. “They’re merely following orders.”

“But it’s Biata!” Astasia was ashamed to hear how high and tremulous her own voice sounded. She was trying to behave as the heir to the Orlov dynasty should. And yet all she felt was a cold, sick sense of dread. They had wanted to kill anyone who was associated with her family. It could have been her own body slung like an animal carcass into that cart.

“I would have preferred to spare you such sights.” Roskovski shot a disapproving glance at the Tielen officer leading them.

The city now lay muffled in the winter dusk, eerily quiet after the din of the riot. Smoke still rose from the ruins of the West Wing; the choking smell of ash and cinders singed the evening air.

“Where are you taking me?” she asked the Tielen officer as they passed through the inner courtyard and entered the palace by an obscure door. A stone stair led into a dank subterranean passageway, lit by links set in the wall.

“This is no place to bring the altessa,” protested Roskovski.

A smell of mold pervaded the air and the floor was puddled with water; Astasia lifted her skirts high, wondering uneasily whether she had walked into some Tielen trap.

“Is this part of the servants’ quarters?” she asked, glancing at Roskovski for reassurance. “I don’t remember ever coming here before.”

Roskovski cleared his throat awkwardly. “This leads to the rooms used by your father’s agents to detain and question those suspected of crimes against the state.”

Astasia stopped. “The old dungeons from my great-grandfather’s time? But my father had them converted to wine cellars. He wouldn’t condone the use of such ancient, unsanitary conditions for—” She stopped. How naïve she sounded. There was so much she did not know about her father’s rule as Grand Duke. Now she began to wonder what cruel tortures had been inflicted down here in the interests of the state, while, unknowing, she had danced at her first ball in the palace above. There was so much she had been shielded from. Had the rioters imprisoned her parents down here? Had they put them to the question? The sick feeling in her stomach grew stronger, as did the unwholesome smell. It was as if the dank water glistening on the walls and pooling on the floor were oozing in from the Nieva, bringing with it the city’s stinking effluent.

At the end of the tunnel they came out into a small room. At a desk sat a tall, broad-shouldered man in Tielen uniform, poring over dispatches by lanternlight. When he stood up to greet her, he had to stoop, the ceiling was so low.

“Karonen at your service, altessa.”

“My parents,” Astasia burst out. “Where are they?”

Field Marshal Karonen cleared his throat, evidently uncomfortable. “That is why I requested your presence in this wretched place, altessa. This is where the insurgents imprisoned them. Now they are reluctant to come out, fearing further ill-treatment. I am hoping you might persuade them that the insurrection is at an end.”

They sat side by side on a wooden bench, blinking in the lanternlight of a cramped, windowless cell. There was an unmistakably fetid odor of stale urine and unwashed flesh. How long had they been imprisoned here? At first Astasia did not even recognize her mother in the lank-haired, listless woman who stared blankly at her.

“Mama, Papa,” she said, her voice trembling, her arms outstretched.

The Grand Duke half-rose from the bench.

“Tasia? Little Tasia?” he said, his voice trembling too.

“Yes, Papa, it’s really me.” Astasia flung her arms around him and hugged him tightly.

“Look, Sofie, it’s Tasia,” the Grand Duke said.

The Grand Duchess gazed at her, her face still expressionless.

“Mama,” Astasia said, kneeling beside her mother, “we’re all safe now.”

“Safe?” the Grand Duchess said with a little shiver. “Did they molest you, Tasia? Did they lay hands on you?”

“No, Mama. I’m fine. But you’re not. You must come out of this cold, damp place and warm yourself.”

The Grand Duchess shrank back, cowering behind her husband. “No, no, it’s not safe. They’re in the palace. They’re everywhere. They want to kill us.”

“Mama, look who’s with me.” Astasia took her mother’s chill hand and pressed it between her own. “It’s Field Marshal Karonen of Tielen. He has taken the city from the rebels. He has rescued us all.”

“Tielen?” said the Grand Duchess distantly. “Now I remember. You were betrothed to Eugene of Tielen, weren’t you, child?”

“Come, Mama,” coaxed Astasia. “Come with me. Wouldn’t you like some hot bouillon? And clean clothes?”

The Grand Duchess glanced nervously at the officers standing in the doorway to the cell. Then she clasped Astasia’s hand. “All right, my dear,” she said in a wavering voice, “but only if you’re certain it’s safe.”

Safe? Astasia thought as her mother ventured out of the cell, leaning heavily on her arm. Poor, foolish Mama. If I’ve learned one thing in the past weeks, it’s that nowhere is safe anymore.

Astasia stood in an anteroom in the East Wing, gazing around her. Slander—hateful, obscene slander—had been daubed in red paint across the pale blue and white walls. The windowpanes had been smashed. And she did not want to look too closely at what had been smeared over the polished floors. The rioters had slashed or defaced everything in their path that they had been unable to carry away; everywhere she saw the evidence of their hatred. But at least the East Wing was intact and her parents were being warmed, cossetted, and fed by the few faithful servants who had not fled.

She was not in any mood to be comforted. Her home had been violated. She hugged her arms around herself, chilled by an all-pervading feeling of desolation.

Feodor Velemir had foreseen all this. Had she judged him too harshly? Had he anticipated the coming storm and sought to pre- vent it?

“Altessa.”

She swung around to see the broad-shouldered bulk of Field Marshal Karonen filling the doorway.

“I have news of his highness for you, from Azhkendir.” He came in, followed by several of his senior officers. The winter-grey and blue colors of the Tielen army filled the antechamber.

“News?”

“Prince Eugene has been gravely wounded,” said Karonen brusquely, “in a battle with the Drakhaon.”

The daemon-shadow of the Drakhaon suddenly billowed up, dark as smoke, in her mind.

“Ah,” she said carefully, aware they were all watching for her reaction. “Wounded—but not killed?”

“We’ve lost many men, but the prince is alive. Magus Linnaius is tending to his injuries. The prince was most anxious to ensure that you were unharmed. He would like to speak with you.”

“With me?” Astasia looked at him, uncomprehending. “But how?”

“It is called a Vox Aethyria.”

When he showed her, she wondered if the Field Marshal had taken leave of his senses. She saw only an exquisite crystal flower—a rose, perhaps—encased in an elaborate tracery of precious metals and glass.

“It’s very pretty, Field Marshal, but—”

“You must approach the device and speak very slowly and clearly. The crystal array will transmit your voice through the air to his highness.”

“What should I say?”

“I believe his highness has a question he is most eager to ask you.”

“Altessa Astasia.”

Astasia, startled, took a step back from the crystal. A man’s voice had addressed her from the heart of the rose. “What kind of trickery is this?”

“No trickery, altessa, I assure you,” said Karonen, his dour expression relaxing into a smile. He turned the Vox toward him and spoke into it. “The altesssa is unused to our Tielen scientific artistry, highness. She is recovering from her surprise at hearing your voice from so far away.” He beckoned Astasia to his side.

Astasia felt her cheeks tingle with indignation. She was not going to be shown up as an unsophisticated schoolgirl. She was an Orlov. What would her father have done on such an occasion? She approached the Vox Aethyria with determination and said loudly and clearly, “I must thank your highness, on behalf of our city, for sending your men to quell the riots and rescue my family. I—I trust you are making a good recovery from your injuries?”

Field Marshal Karonen nodded his approval and adjusted the Vox so that she could hear Prince Eugene’s reply.

It was faint at first, so that she had to bend closer to the crystal to hear.

“Indeed; and I am in much better spirits already for hearing your voice, and knowing you are safe.” Formal as his words were, she thought she detected—to her surprise—an undertone of genuine concern. Does he care about me a little, then? “I had fully intended to lead my men to free the city myself, but fate decreed otherwise. Now I want nothing more than to meet you. I’ve had to wait far too long and, charming though your portrait is, it’s a poor substitute.”

Astasia’s throat had gone dry. She could sense what was coming next. Am I ready for this?

“We must meet, altessa, and soon. I have plans—great plans—for our two countries, but unless you are at my side, they will all be meaningless. Will you marry me, Astasia?”

“The altessa will not be disappointed, highness.” The valet straightened the blue ribbon of the Order of the Swan on Eugene’s breast, gave one final tweak to the fine linen collar, a last spray of cologne, and withdrew from the prince’s bedchamber, bowing.

Eugene of Tielen forced himself to confront his reflection in the cheval mirror.

At first he had ordered all mirrors in the palace at Swanholm to be covered, unable to bear the ravages that his encounter with the Drakhaon had wrought. Now that he was almost recovered, he forced himself to look every day. After all, he reasoned, his courtiers were obliged to put up with the sight of his disfigurement, so why shouldn’t he?

He had never been vain. He had known himself to be strong- featured—certainly no handsome fairy-tale prince from one of Karila’s stories. But it still pained him to see the ravages of the Drakhaon’s Fire: the scarred and reddened skin that pitted one hand and one whole side of his face and head. And his hair had not yet grown back as he had hoped, though there were signs of a soft, pale ashen fuzz, the rich golden hues bleached away.

How would Astasia react? Would she shrink from him, forced by court protocol to make a public show of tolerating what, in her heart, she looked on with revulsion? Or was she made of stronger stuff, prepared to search deeper than superficial appearances?

He squared his shoulders, bracing himself. He had conquered a whole continent; what had he to fear from one young woman?

He pushed open the double doors and went to meet his betrothed for the first time.

The East Wing music room had escaped the worst of the attack. Built for intimate concerts and recitals, it was crammed to overflowing with the military dignitaries of the Tielen royal household, leaving little room for the Orlov family and their court.

Astasia sat on a dais between her parents; a fourth gilt chair stood empty beside hers. First Minister Vassian stood silently behind her. Still in mourning for her drowned brother Andrei, her family and the court were somberly dressed in black and violet. A tense silence filled the room; the Mirom courtiers seemed too bewildered by the rapid succession of events that had led to the annexation of Muscobar even to whisper behind their black-gloved hands.

A blaze of military trumpets shattered the air.

“His imperial highness, Eugene of Tielen!” announced a martial voice.

The Tielen household guard came marching in, spurs clanking. Astasia felt her mother shrink in her seat.

“It’s all right, Mama,” she whispered, patting her hand, trying to suppress her own nervousness. Then she saw all the heads in the room bowing, the women sinking into low curtsies.

He was here.

She rose to her feet, pressing her hands together to stop them from shaking.

Prince Eugene came in, accompanied by Field Marshal Karonen. She noted that he too wore a black velvet mourning band. Was it as a sign of respect for their loss, or had he too lost someone dear to him in the fighting?

They had warned her about his injuries. She did not think herself squeamish, but she steeled herself nevertheless, hoping she would not let anything of what she might feel show on her face.

He stood before her, but still she stared at the golden Order of the Swan glittering on his breast, unwilling to meet his eyes.

“Welcome, your highness,” she said, dropping into a full court curtsy, one hand extended in formal greeting.

She sensed a slight hesitation, then a gloved hand took hers in a firm grip, raising her to her feet. Still she did not dare to look at him, even as she felt him lift her hand to his lips.

Look, you must look, she willed herself, aware that everyone in the room was watching them with bated breath.

“You are every bit as beautiful as your portrait, altessa.” His voice was strong, confident, colored by a slight Tielen accent. He still held her hand in his.

She could no longer keep her gaze lowered. She looked at him then, forcing herself to concentrate on his eyes. Blue-grey eyes, clear and cold as a winter’s morning, gazed steadily back. But all the skin around them was red, blistered, and damaged. She was looking into the ruin of a face.

Gavril did this. She was so shocked she could not speak for a moment. How cruel.

“You flatter me, your highness,” she answered, forcing firmness into her voice. She must not forget that this was also the man who had ruthlessly ordered Elysia’s execution. “Please . . .” She gestured to the gilt chair that had been set for him beside hers.

He stepped up onto the dais, towering above her. He bowed to the Grand Duke and Duchess, to Vassian, and then sat down.

Astasia cleared her throat. This was the part of the ceremony she had been dreading the most—because it signaled to the world the end of the Orlov dynasty.

Her father rose from his chair and took her hand in his.

“My—my daughter has a gift for you, your highness,” he said. His voice faltered. “A gift from the heart of Muscobar. Accept it—and with it, her hand in marriage, freely given, so that our two countries may be united as one.”

Astasia took the jeweled casket her father was holding toward her and knelt before Prince Eugene, offering it with both hands raised.

The prince opened the casket. The Mirom Ruby glowed in his fingers like a flame as he held it aloft: a victory trophy.

“The last of Artamon’s Tears!” His voice throbbed now with an intensity of emotion that startled Astasia. “Now the imperial crown is complete.” He helped her to rise and took her hand, closing it over the ancient ruby clutched in his fingers.

“Today a new empire rises from the ashes of Artamon’s dreams. Altessa, from the day we are married in the Cathedral of Saint Simeon, you will be known as Astasia, Empress of New Rossiya.”

He drew her close and she felt—as if in a waking dream—the pressure of his burned lips, hot and dry, on her forehead, and then her mouth.

Field Marshal Karonen turned to the astonished court.

“Long live the Emperor Eugene—and Empress Astasia!”

After a short, startled silence, the cheers began. Astasia, her hand still in Eugene’s, glanced at her father—and saw the Grand Duke surreptitiously wiping away a tear.

From the Hardcover edition.

Chapter 1

W Astasia Orlova leaned on the rail of the Tielen ship that was carrying her back home to Muscobar across the Straits. Cold seaspray blew into her face, her hair, but she did not care.

She was bearing Count Velemir’s ashes back to Mirom. It was Feodor Velemir who had brought her to Tielen on the pretense that wreckage from her brother Andrei’s command, the Sirin, had been washed up on the shore. She had gone, eager that there might be the faintest glimmer of hope that Andrei was not drowned but lying injured in some remote fisherman’s hut, only to find that it had all been a ruse to display her charms to the Tielen court and council, to persuade them that she would make a suitable bride for Prince Eugene.

Well, Count, she thought, gazing into the rolling sea mist that hid the coastline of Muscobar from view, you have paid the ultimate price for your treachery. You used me heartlessly. You lied, you twisted the truth to further your own ends, and now you are dead.

But even now she was not sure she believed the evidence of her own eyes. What she had witnessed in the snowy palace yard had shaken her to the very core.

There crouched a dark-winged creature, veiled in a blue shimmer of heat. And—most horrible of all—the burning remains of something that had once been Feodor Velemir, Muscobar’s ambassador to Tielen, lay in a charred, smoking heap at its feet.

Drakhaon.

In that one moment all certainties had been seared away.

“Altessa!” Nadezhda, her maid, came up to her, carrying a wool shawl. “You’ll catch a chill up here in this bitter wind.”

“Don’t fuss, Nadezhda. I’m fine.”

Nadezhda took no notice and draped the shawl over Astasia’s shoulders. “Please come below and warm yourself.”

“Not yet,” Astasia said distantly. “In a while . . .”

The cloudy sky and the choppy sea mirrored her mood. She felt numbed. Whenever she tried to sleep, she saw the Drakhaon of Azhkendir rear up out of the darkness and then, oh then—

The one moment she could not forget, the moment when the dragon-winged daemon had turned its piercing blue gaze on her and she had recognized Gavril Andar.

Elysia Andar had tried to warn her, but she had refused to listen. Yet now she knew it to be true. Gavril, the one man she had ever allowed to hold her, to kiss her, was possessed by a dragon-daemon—

“Altessa.”

She turned to see that one of the Tielen officers had come up on deck.

“We have received an urgent message from Mirom, altessa, that concerns you. Will you please come below?”

Reluctantly, Astasia followed him belowdecks to the captain’s anteroom. Chancellor Maltheus had sent an escort of the household guard to protect her . . . or to prevent her from running away?

A group of officers were gathered around the table; they bowed as she entered.

“Is there a storm coming?” she asked, taking off the shawl. The fine mist of seaspray still clung to her hair. “Should we seek harbor and sit it out?”

“The message comes from Field Marshal Karonen, altessa. He reports there is rioting in Mirom. It seems that your parents have been trapped in the Winter Palace by a mob of dissidents who are threatening to torch the palace and all inside.”

Astasia gripped the edge of the table to steady herself. “Dissidents?” she repeated.

“Your father has requested our help. It seems the situation is quite desperate.”

“My father is asking for help?” Astasia said. If nothing else, this brought home the severity of the situation. Her father never asked for help.

“The Field Marshal is ready to lead a rescue force into the city, altessa. Just give the word and he will liberate the palace.”

Astasia gazed warily around at all the Tielen officers. She could not help noticing the detailed map of Mirom that lay outspread on the table. They seemed so well-prepared. . . .

“We understand there has been unrest in the city for some months,” said one.

“Well, yes—” she began, then broke off. How could she have been so blind? Maltheus had sent the soldiers with her as part of the invasion force. What better way to infiltrate Tielen soldiers into the heart of the city? Dissidents or no, Muscobar was about to be swallowed up into the growing Tielen empire.

“Prince Eugene is determined to quell any last stirrings of rebellion before your wedding takes place.”

“Of course,” she said coldly. They were still looking at her expectantly, and she realized that they were waiting for her command.

“Tell the Field Marshal,” she said, knowing she had no choice, “to put down the rebellion—and with my blessing.”

Astasia struggled up on deck against the prevailing wind, into a raw, red dawn. As the ship sailed up the broad Nieva, she noticed that the gilded dome of the Senate House had been reduced to a smoldering shell. And while at first she had believed the red glare in the sky to be the rising sun, surely no dawn could glow that brightly?

No, the West Wing of the palace was on fire.

She heard the crackle of the flames, the tinkle of breaking glass as panes burst in the heat; she saw the haze of smoke sullying the freshness of the dawn.

They were burning her home.

“No!” she cried aloud, gripping the rail to steady herself.

Now she could hear shouts from the shore; a confusion of people was swarming over the neatly clipped boxes and yews. Guards leaned from the windows, aiming muskets at the rabble, firing. A ragged rat-a-tat of fusillades answered.

“You must go belowdecks, altessa!” One of the Tielen officers came toward her, pistol in hand. “It’s not safe up here!”

Screams carried on the wind, shrill above the rattle of gunfire. There were running silhouettes at the West Wing windows, dark against the blaze of the flames. Where were Mama and Papa? Where was her governess, poor, dear Eupraxia? She would be so flustered by the panic and the fire—

“There are people trapped in there!” she said to the officer, grabbing his arm and stabbing her finger at the burning building. “We must get them out!”

A musket ball whizzed over their heads, grazing the nearest mast, showering them with sharp splinters of wood.

“We’re doing all we can,” he said, hurrying her toward the hatch.

The battle for the Winter Palace lasted little more than an hour. Astasia crept back up on deck and watched as more and more Tielen soldiers swarmed into the gardens, driving the rebels before them, rounding them up at musket-point.

By now the West Wing was well-alight, and she saw looters risk- ing the Tielen guns to carry away brocade curtains, pictures, fine porcelain . . . Too late, some servants formed a bucket-chain while others water from the river. Flames burst through the roof. Rafters cracked and the whole structure collapsed inward with a crash like rolling thunder.

Shocked beyond speech, she stood with her hands clutched to her mouth. The clouds of acrid smoke carried the vile smell of burning: timber, molten glass, and, worst of all, human flesh.

“I’ve made some tea, altessa.” She had not noticed that Nadezhda had emerged from belowdecks. “You’ve eaten nothing for hours. You need to keep up your strength.”

“Mama,” Astasia whispered into the billowing smoke. “Papa . . .”

“Tea with a drop of brandy, that’ll warm you up.” Nadezhda took her by the arm and steered her back below.

At about four in the afternoon, a party of Muscobar officers came on board and asked to speak with her. Sick with worry, she hurried to meet them.

“Colonel Roskovski!” she cried, so glad to see a familiar face that she wanted to run up and hug him.

“Altessa,” he said, clicking his heels and saluting her. He looked haggard; he was unshaven and his immaculate white uniform jacket was covered in smears of soot. “Thank God you’re safe.”

“Is there . . . is there any news of my parents?”

“They are under the protection of Field Marshal Karonen,” he said stiffly.

“But they’re alive?”

“I believe so. Altessa—” he hesitated. “I have been obliged to surrender control of the city to the Field Marshal.” She saw now that not only was he exhausted, but there were tears in his smoke-reddened eyes—tears of humiliation and defeat. “I am dishonored. I have failed your father.”

“Not surrender, Colonel,” she said, dismayed that such a proud and experienced soldier should openly weep with shame in front of her. “I’m sure you and your men did everything you could to save the city. But the odds were overwhelming. Without Tielen’s help—”

“Altessa Astasia!” One of the Tielen officers came running up. “The Field Marshal requests a meeting.”

Her heart began to beat overfast, a butterfly trapped in her breast. This was to do with her parents, she was sure of it. How would she find them? Even if they were physically unharmed, the last few days would have taken a terrible toll on Mama’s nerves. And Papa . . .

“Colonel,” she said, “please accompany me.”

It seemed that there were Tielen soldiers everywhere: lining the quay as Astasia disembarked, guarding the Water Gate, and patrolling the outer walls where the rebels had smashed down the iron railings as they stormed the palace.

Even though the officers steered a carefully chosen path, Astasia saw soldiers carrying out bodies from the courtyards and piling them onto carts. Through an archway she glimpsed some of Roskovski’s men cutting down a palace guard who was hanging from a lamppost, his white uniform red with his own blood.

“Were many killed?” she asked, determined that she should not be treated like a child.

“Enough,” Roskovski said tersely.

She wanted to avert her gaze from the bodies, but found she could not look away. One bright head of hair, as fiery as a fox’s pelt, caught her eye. One of her mother’s maids, Biata, had hair of just that unusual shade. . . .

The woman’s head lolled at an unnatural angle over the edge of the cart, eyes fixed, staring out from a wax-pale face. A trickle of blood from both nostrils darkened her lips, her chin.

“Biata?” But what point was there in calling her name when she was beyond hearing? And even as Astasia watched, the Tielens unceremoniously flung another body onto the cart, right on top of her. They were not distinguishing rioters from palace servants, they were just clearing away corpses.

Astasia started forward, outraged, and felt a firm touch on her shoulder.

“These men mean no disrespect,” said Roskovski. “They’re merely following orders.”

“But it’s Biata!” Astasia was ashamed to hear how high and tremulous her own voice sounded. She was trying to behave as the heir to the Orlov dynasty should. And yet all she felt was a cold, sick sense of dread. They had wanted to kill anyone who was associated with her family. It could have been her own body slung like an animal carcass into that cart.

“I would have preferred to spare you such sights.” Roskovski shot a disapproving glance at the Tielen officer leading them.

The city now lay muffled in the winter dusk, eerily quiet after the din of the riot. Smoke still rose from the ruins of the West Wing; the choking smell of ash and cinders singed the evening air.

“Where are you taking me?” she asked the Tielen officer as they passed through the inner courtyard and entered the palace by an obscure door. A stone stair led into a dank subterranean passageway, lit by links set in the wall.

“This is no place to bring the altessa,” protested Roskovski.

A smell of mold pervaded the air and the floor was puddled with water; Astasia lifted her skirts high, wondering uneasily whether she had walked into some Tielen trap.

“Is this part of the servants’ quarters?” she asked, glancing at Roskovski for reassurance. “I don’t remember ever coming here before.”

Roskovski cleared his throat awkwardly. “This leads to the rooms used by your father’s agents to detain and question those suspected of crimes against the state.”

Astasia stopped. “The old dungeons from my great-grandfather’s time? But my father had them converted to wine cellars. He wouldn’t condone the use of such ancient, unsanitary conditions for—” She stopped. How naïve she sounded. There was so much she did not know about her father’s rule as Grand Duke. Now she began to wonder what cruel tortures had been inflicted down here in the interests of the state, while, unknowing, she had danced at her first ball in the palace above. There was so much she had been shielded from. Had the rioters imprisoned her parents down here? Had they put them to the question? The sick feeling in her stomach grew stronger, as did the unwholesome smell. It was as if the dank water glistening on the walls and pooling on the floor were oozing in from the Nieva, bringing with it the city’s stinking effluent.

At the end of the tunnel they came out into a small room. At a desk sat a tall, broad-shouldered man in Tielen uniform, poring over dispatches by lanternlight. When he stood up to greet her, he had to stoop, the ceiling was so low.

“Karonen at your service, altessa.”

“My parents,” Astasia burst out. “Where are they?”

Field Marshal Karonen cleared his throat, evidently uncomfortable. “That is why I requested your presence in this wretched place, altessa. This is where the insurgents imprisoned them. Now they are reluctant to come out, fearing further ill-treatment. I am hoping you might persuade them that the insurrection is at an end.”

They sat side by side on a wooden bench, blinking in the lanternlight of a cramped, windowless cell. There was an unmistakably fetid odor of stale urine and unwashed flesh. How long had they been imprisoned here? At first Astasia did not even recognize her mother in the lank-haired, listless woman who stared blankly at her.

“Mama, Papa,” she said, her voice trembling, her arms outstretched.

The Grand Duke half-rose from the bench.

“Tasia? Little Tasia?” he said, his voice trembling too.

“Yes, Papa, it’s really me.” Astasia flung her arms around him and hugged him tightly.

“Look, Sofie, it’s Tasia,” the Grand Duke said.

The Grand Duchess gazed at her, her face still expressionless.

“Mama,” Astasia said, kneeling beside her mother, “we’re all safe now.”

“Safe?” the Grand Duchess said with a little shiver. “Did they molest you, Tasia? Did they lay hands on you?”

“No, Mama. I’m fine. But you’re not. You must come out of this cold, damp place and warm yourself.”

The Grand Duchess shrank back, cowering behind her husband. “No, no, it’s not safe. They’re in the palace. They’re everywhere. They want to kill us.”

“Mama, look who’s with me.” Astasia took her mother’s chill hand and pressed it between her own. “It’s Field Marshal Karonen of Tielen. He has taken the city from the rebels. He has rescued us all.”

“Tielen?” said the Grand Duchess distantly. “Now I remember. You were betrothed to Eugene of Tielen, weren’t you, child?”

“Come, Mama,” coaxed Astasia. “Come with me. Wouldn’t you like some hot bouillon? And clean clothes?”

The Grand Duchess glanced nervously at the officers standing in the doorway to the cell. Then she clasped Astasia’s hand. “All right, my dear,” she said in a wavering voice, “but only if you’re certain it’s safe.”

Safe? Astasia thought as her mother ventured out of the cell, leaning heavily on her arm. Poor, foolish Mama. If I’ve learned one thing in the past weeks, it’s that nowhere is safe anymore.

Astasia stood in an anteroom in the East Wing, gazing around her. Slander—hateful, obscene slander—had been daubed in red paint across the pale blue and white walls. The windowpanes had been smashed. And she did not want to look too closely at what had been smeared over the polished floors. The rioters had slashed or defaced everything in their path that they had been unable to carry away; everywhere she saw the evidence of their hatred. But at least the East Wing was intact and her parents were being warmed, cossetted, and fed by the few faithful servants who had not fled.

She was not in any mood to be comforted. Her home had been violated. She hugged her arms around herself, chilled by an all-pervading feeling of desolation.

Feodor Velemir had foreseen all this. Had she judged him too harshly? Had he anticipated the coming storm and sought to pre- vent it?

“Altessa.”

She swung around to see the broad-shouldered bulk of Field Marshal Karonen filling the doorway.

“I have news of his highness for you, from Azhkendir.” He came in, followed by several of his senior officers. The winter-grey and blue colors of the Tielen army filled the antechamber.

“News?”

“Prince Eugene has been gravely wounded,” said Karonen brusquely, “in a battle with the Drakhaon.”

The daemon-shadow of the Drakhaon suddenly billowed up, dark as smoke, in her mind.

“Ah,” she said carefully, aware they were all watching for her reaction. “Wounded—but not killed?”

“We’ve lost many men, but the prince is alive. Magus Linnaius is tending to his injuries. The prince was most anxious to ensure that you were unharmed. He would like to speak with you.”

“With me?” Astasia looked at him, uncomprehending. “But how?”

“It is called a Vox Aethyria.”

When he showed her, she wondered if the Field Marshal had taken leave of his senses. She saw only an exquisite crystal flower—a rose, perhaps—encased in an elaborate tracery of precious metals and glass.

“It’s very pretty, Field Marshal, but—”

“You must approach the device and speak very slowly and clearly. The crystal array will transmit your voice through the air to his highness.”

“What should I say?”

“I believe his highness has a question he is most eager to ask you.”

“Altessa Astasia.”

Astasia, startled, took a step back from the crystal. A man’s voice had addressed her from the heart of the rose. “What kind of trickery is this?”

“No trickery, altessa, I assure you,” said Karonen, his dour expression relaxing into a smile. He turned the Vox toward him and spoke into it. “The altesssa is unused to our Tielen scientific artistry, highness. She is recovering from her surprise at hearing your voice from so far away.” He beckoned Astasia to his side.

Astasia felt her cheeks tingle with indignation. She was not going to be shown up as an unsophisticated schoolgirl. She was an Orlov. What would her father have done on such an occasion? She approached the Vox Aethyria with determination and said loudly and clearly, “I must thank your highness, on behalf of our city, for sending your men to quell the riots and rescue my family. I—I trust you are making a good recovery from your injuries?”

Field Marshal Karonen nodded his approval and adjusted the Vox so that she could hear Prince Eugene’s reply.

It was faint at first, so that she had to bend closer to the crystal to hear.

“Indeed; and I am in much better spirits already for hearing your voice, and knowing you are safe.” Formal as his words were, she thought she detected—to her surprise—an undertone of genuine concern. Does he care about me a little, then? “I had fully intended to lead my men to free the city myself, but fate decreed otherwise. Now I want nothing more than to meet you. I’ve had to wait far too long and, charming though your portrait is, it’s a poor substitute.”

Astasia’s throat had gone dry. She could sense what was coming next. Am I ready for this?

“We must meet, altessa, and soon. I have plans—great plans—for our two countries, but unless you are at my side, they will all be meaningless. Will you marry me, Astasia?”

“The altessa will not be disappointed, highness.” The valet straightened the blue ribbon of the Order of the Swan on Eugene’s breast, gave one final tweak to the fine linen collar, a last spray of cologne, and withdrew from the prince’s bedchamber, bowing.

Eugene of Tielen forced himself to confront his reflection in the cheval mirror.

At first he had ordered all mirrors in the palace at Swanholm to be covered, unable to bear the ravages that his encounter with the Drakhaon had wrought. Now that he was almost recovered, he forced himself to look every day. After all, he reasoned, his courtiers were obliged to put up with the sight of his disfigurement, so why shouldn’t he?

He had never been vain. He had known himself to be strong- featured—certainly no handsome fairy-tale prince from one of Karila’s stories. But it still pained him to see the ravages of the Drakhaon’s Fire: the scarred and reddened skin that pitted one hand and one whole side of his face and head. And his hair had not yet grown back as he had hoped, though there were signs of a soft, pale ashen fuzz, the rich golden hues bleached away.

How would Astasia react? Would she shrink from him, forced by court protocol to make a public show of tolerating what, in her heart, she looked on with revulsion? Or was she made of stronger stuff, prepared to search deeper than superficial appearances?

He squared his shoulders, bracing himself. He had conquered a whole continent; what had he to fear from one young woman?

He pushed open the double doors and went to meet his betrothed for the first time.

The East Wing music room had escaped the worst of the attack. Built for intimate concerts and recitals, it was crammed to overflowing with the military dignitaries of the Tielen royal household, leaving little room for the Orlov family and their court.

Astasia sat on a dais between her parents; a fourth gilt chair stood empty beside hers. First Minister Vassian stood silently behind her. Still in mourning for her drowned brother Andrei, her family and the court were somberly dressed in black and violet. A tense silence filled the room; the Mirom courtiers seemed too bewildered by the rapid succession of events that had led to the annexation of Muscobar even to whisper behind their black-gloved hands.

A blaze of military trumpets shattered the air.

“His imperial highness, Eugene of Tielen!” announced a martial voice.

The Tielen household guard came marching in, spurs clanking. Astasia felt her mother shrink in her seat.

“It’s all right, Mama,” she whispered, patting her hand, trying to suppress her own nervousness. Then she saw all the heads in the room bowing, the women sinking into low curtsies.

He was here.

She rose to her feet, pressing her hands together to stop them from shaking.

Prince Eugene came in, accompanied by Field Marshal Karonen. She noted that he too wore a black velvet mourning band. Was it as a sign of respect for their loss, or had he too lost someone dear to him in the fighting?

They had warned her about his injuries. She did not think herself squeamish, but she steeled herself nevertheless, hoping she would not let anything of what she might feel show on her face.

He stood before her, but still she stared at the golden Order of the Swan glittering on his breast, unwilling to meet his eyes.

“Welcome, your highness,” she said, dropping into a full court curtsy, one hand extended in formal greeting.

She sensed a slight hesitation, then a gloved hand took hers in a firm grip, raising her to her feet. Still she did not dare to look at him, even as she felt him lift her hand to his lips.

Look, you must look, she willed herself, aware that everyone in the room was watching them with bated breath.

“You are every bit as beautiful as your portrait, altessa.” His voice was strong, confident, colored by a slight Tielen accent. He still held her hand in his.

She could no longer keep her gaze lowered. She looked at him then, forcing herself to concentrate on his eyes. Blue-grey eyes, clear and cold as a winter’s morning, gazed steadily back. But all the skin around them was red, blistered, and damaged. She was looking into the ruin of a face.

Gavril did this. She was so shocked she could not speak for a moment. How cruel.

“You flatter me, your highness,” she answered, forcing firmness into her voice. She must not forget that this was also the man who had ruthlessly ordered Elysia’s execution. “Please . . .” She gestured to the gilt chair that had been set for him beside hers.

He stepped up onto the dais, towering above her. He bowed to the Grand Duke and Duchess, to Vassian, and then sat down.

Astasia cleared her throat. This was the part of the ceremony she had been dreading the most—because it signaled to the world the end of the Orlov dynasty.

Her father rose from his chair and took her hand in his.

“My—my daughter has a gift for you, your highness,” he said. His voice faltered. “A gift from the heart of Muscobar. Accept it—and with it, her hand in marriage, freely given, so that our two countries may be united as one.”

Astasia took the jeweled casket her father was holding toward her and knelt before Prince Eugene, offering it with both hands raised.

The prince opened the casket. The Mirom Ruby glowed in his fingers like a flame as he held it aloft: a victory trophy.

“The last of Artamon’s Tears!” His voice throbbed now with an intensity of emotion that startled Astasia. “Now the imperial crown is complete.” He helped her to rise and took her hand, closing it over the ancient ruby clutched in his fingers.

“Today a new empire rises from the ashes of Artamon’s dreams. Altessa, from the day we are married in the Cathedral of Saint Simeon, you will be known as Astasia, Empress of New Rossiya.”

He drew her close and she felt—as if in a waking dream—the pressure of his burned lips, hot and dry, on her forehead, and then her mouth.

Field Marshal Karonen turned to the astonished court.

“Long live the Emperor Eugene—and Empress Astasia!”

After a short, startled silence, the cheers began. Astasia, her hand still in Eugene’s, glanced at her father—and saw the Grand Duke surreptitiously wiping away a tear.

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

Gavril Nagarian has rid himself of the taint in his blood--but at a price. With the Drakhaoul no longer possessing his soul, he is imprisoned in the Iron Tower where he is slowly being driven mad. Worse, Eugene has made his move and annexed Gavril's lands.