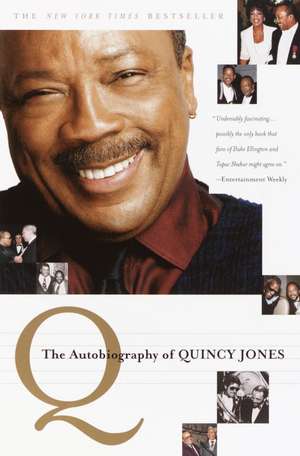

Q

Autor Quincy Jonesen Limba Engleză Paperback – 8 oct 2002

Quincy Jones grew up poor on the mean streets of Chicago’s South Side, brushing against the law and feeling the pain of his mother’s descent into madness. But when his father moved the family west to Seattle, he took up the trumpet and was literally saved by music. A prodigy, he played backup for Billie Holiday and toured the world with the Lionel Hampton Band before leaving his teens. Soon, though, he found his true calling, inaugurating a career whose highlights have included arranging albums for Frank Sinatra, Ray Charles, Dinah Washington, Sarah Vaughan, and Count Basie; composing the scores of such films as The Pawnbroker, In Cold Blood, In the Heat of the Night, and The Color Purple, and the theme songs for the television shows Ironside, Sanford and Son, and The Cosby Show; producing the bestselling album of all time, Michael Jackson’s Thriller, and the bestselling single “We Are the World”; and producing and arranging his own highly praised albums, including the Grammy Award—winning Back on the Block, a striking blend of jazz, African, urban, gospel, and hip-hop. His musical achievements, in a career that spans every style of American popular music, have yielded an incredible seventy-seven Grammy nominations, and are matched by his record as a pioneering music executive, film and television producer, tireless social activist, and business entrepreneur–one of the most successful black business figures in America. This string of unbroken triumphs in the entertainment industry has been shadowed by a turbulent personal life, a story he shares with eloquence and candor.

Q is an impressive self-portrait by one of the master makers of American culture, a complex, many-faceted man with far more than his share of talents and an unparalleled vision, as well as some entirely human flaws. It also features vivid testimony from key witnesses to his journey–family, friends, and musical and business associates. His life encompasses an astonishing cast of show business giants, and provides the raw material for one of the great African American success stories of this century.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 116.92 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 175

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.38€ • 24.32$ • 18.81£

22.38€ • 24.32$ • 18.81£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767905107

ISBN-10: 0767905105

Pagini: 432

Ilustrații: 32 PAGES OF B&W PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 154 x 242 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.49 kg

Editura: Crown Publishing Group (NY)

ISBN-10: 0767905105

Pagini: 432

Ilustrații: 32 PAGES OF B&W PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 154 x 242 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.49 kg

Editura: Crown Publishing Group (NY)

Notă biografică

QUINCY JONES's most recent major award is the Thurgood Marshall Lifetime Achievement Award from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund; his most recent release is From Q with Love. He lives in Los Angeles, California.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter 1

The promise

I remember the cold. It was a stinging, backbreaking, bone-chilling Kentucky-winter cold, the kind of cold that makes you feel like you're freezing from the inside out, the kind of cold that makes you feel like you'll never be warm again. I had no music in me then, just sounds, the shrill noise the back door made when it creaked open, the funny grunts my little brother Lloyd made while we slept together, the tight, muffled squeals that rats made when the rat traps snapped them in half. My grandmother did not believe in wasting anything. She had nothing to waste. She cooked whatever she could get her hands on. Mustard greens, okra, possum, chickens, and rats, and me and Lloyd ate them all. We ate the fried rats because we were nine and seven years old and we did what we were told. We ate them because my grandma could cook them well. But most of all, we ate them because that's all there was to eat.

My mother had gone away sick one day and she never came back. That's all we knew. That's all my father told us. "She's gone away sick and she'll be back soon," was what he said, but "soon" turned into months and years, so the two of us had left Chicago and gone to Louisville to stay with Grandma. Laying in bed at night in my grandma's house, I could remember the night before my mother left us. We were downstairs in the living room back home in South Side Chicago during the Depression, Lloyd and Daddy and me, and we heard a crash and the noise of a window breaking, and we ran upstairs and I felt the rush of cold air and saw my mother at the broken window looking out into the street. She was wearing only a housedress, standing in the freezing nighttime air, the snow blowing in on her face, and she was singing, "Ohh, ohh, ohh, ohh--oh, somebody touched me and it must have been the hand of the Lord."

As a young boy, I thought it was odd for my mother to sing out the window. She played piano and sang in church, but my mother was a private woman, solid and proper. She never spoke out of turn like that. She did not like loud things or loud people, but her behavior had become more and more strange. She had frequent fainting spells. She would yell at us for no reason. She quoted the Bible and scribbled notes endlessly. The lines around her eyes seemed to grow tighter and tighter every day. Her angry outbursts were crushing affairs, sometimes lasting for days.

My daddy never knew what to do when my mother had spells like this. He was not a complicated man. He was a carpenter for the Jones Boys, the black gangsters who ran the ghetto back in Chicago -- the policy rackets, the Jones five-and-dime stores -- the V and X, as they were known in the 'hood. When my Aunt Mabel asked him once why he worked for hoods and hustlers, he made a funny face and said, "Gangsters need carpenters, too. They're no worse than the gangsters who won't give me jobs." He grew up in Lake City, South Carolina, so I was told, but to be honest I never knew exactly where he was really from. I'd heard his father was a white man-- either Irish or Welsh-- who had killed somebody, and Daddy had to get out of the South because of this, which made as much sense as anything else in my life, because since my mother left us, nothing seemed solid except the black space in my stomach. Daddy was a quiet man, with smooth straight hair, soft brown eyes, and firm face. His shoulders were broad, his arms were thick and muscled, and his hands were gigantic, huge iron fists with fingers as thick as cigars. He'd been a catcher with the Metropolitan Baptist Church team in the Negro Leagues -- he even caught the great Satchel Paige once -- and all those years of catching baseballs with a thin mitt had smashed his fingers and made them flat and crooked. He could bend the first knuckle of each hand and hold them out like claws. His fingers were so strong that he could make a circle with his forefinger and thumb and pop you upside the head so hard it felt like a bullet smashing through your skin. My brother and I called that "the Thump Bump," and when he thumped you, it stung for hours.

He tried to talk to my mother as she stood by the window singing. He said, "Get ahold of yourself, Sarah," but she ignored him and kept singing, so he turned away and went downstairs. As he swept past me I heard him mutter something, so I ran to my mother and told her what he said: "Daddy's gonna send you away," I said, but she didn't hear me. She stood with her back to me, staring out the window, and the next morning my daddy came back upstairs with two ambulance attendants in white and one of them said, "Mrs. Jones, you wanna come get your luggage and things?"

She looked over at him without a word, so he said, "Either you come or we'll carry you."

She said, "Can I take my Bible?"

He said, "You can take it."

She slowly picked up her Bible, then suddenly darted for the door to escape, but the two men grabbed her and threw her down on the bed, spread-eagled. She kicked and screamed as they threw a straightjacket on her and carried her out. We followed her downstairs and sat on the steps. Lucy Jackson held Lloyd on her lap and covered his eyes with her hands. I sat next to them, crying, and covered my eyes too, singing the same song, "Ohh, ohh, ohh, ohh -- oh, somebody touched me and it must have been the hand of the Lord." And just like that she was gone -- for days, weeks, months, who knows how long. Soon after, my daddy packed us up and the three of us headed to St. Louis to stay with relatives, then back to Chicago, then back to St. Louis again, till Daddy finally gave up and took us to Louisville to stay with his mother. Then he left.

We didn't hate it in Louisville. We didn't like it either. My grandma's house was a shotgun shack near the Ohio River with no electricity. We drew our water from a well in her backyard. We got our heat from a black potbellied coal stove. We used kerosene lamps and bathed in a big tin washtub. We slept in the kitchen on a cot next to the back door, which was held closed with a rusty bent nail. When the door was closed in the daytime, you could see daylight all around the doorframe. At night we slept with socks on our hands and feet so the rats wouldn't nibble our fingers and toes. In the wintertime, the floor was frozen and wet in the morning. In summer, it was like fire and the smell of old pee stung my nostrils constantly. Breakfast was grits, lunch was nonexistent, and dinner was whatever my grandmother would find that would fry. The teachers at the Samuel T. Coleridge Colored School wanted to make examples of us as strangers and would march Lloyd and me to the back of the classroom every morning and make us take our shoes off and scrub the dirt off our feet and faces with commercial Lifebuoy soap while the other kids cackled. We had no hot water for washing. They seemed to have no idea who we were. My grandmother didn't understand the 1940 Jefferson County school system either, only the notion that we had to go there. Grandma was a proud, strong woman, a former slave; she was thin, rangy, coal-black, wise, and old. She had African beliefs, like hanging asafetida, a horrid-smelling gumlike bark-and-garlic concoction, on a string around our necks to ward off colds, fever, and bad spirits. She led us to the Baptist church every Sunday and spoke in a tongue that me and Lloyd could barely understand. She had been born a slave and used African words we never heard of, like "mwena" for "kids." She'd say, "Mwena, come over here and lift this tub," or "Mwena, go down yonder to the river and catch me some rats." She told us that the more the rats wiggle their tails, the better they'd taste, so we'd wait by the river, snatch up the biggest ones we could find by the tail, and stuff them in a burlap sack. We were free to roam in Kentucky, that part we liked, but at night it was cold and lonely in that dark shotgun shack and it was too much for me, because I wanted my parents. I was mad at them both, but more mad at my daddy, because he was the one who kept it together. Daddy was the one who was solid. Daddy was the one who said we'd always be together. My brother Lloyd, 16 1/2 months younger than me, would cry at night for his daddy, and one night as we lay in bed, he asked, "Did Daddy go away 'cause he's mad at us?"

"Stop whining," I said. "He'll be back." I had a faint recollection of Daddy promising to come back, but I wasn't sure. He'd been gone a long time. We'd been there a year. Nothing seemed certain.

"I didn't hear him sayin' nothin' about coming back," Lloyd said.

"He'll be back," I said.

"Well, if he's coming back, he oughta come on them."

"Who needs him anyway?" I said. "Stop crying' like a kindygarden baby." But deep inside I was scared and nervous, and each night I fell asleep with my teeth chattering from cold and my heart buried someplace near my feet, until that winter night in 1941 when I heard the back door creak open and I saw a huge shadow blocking the entrance, the breath coming from his mouth in clouds as he moved inside, lit a kerosene lamp, which Grandma called coal oil, and sat down, sighing. My fear and anger dissipated like water as me and Lloyd scrambled out of the bed and landed in his lap.

"You promise me you won't go away and leave us no more," I sobbed. "Promise."

"I promise." My daddy said. And he kept his word.

From the Hardcover edition.

The promise

I remember the cold. It was a stinging, backbreaking, bone-chilling Kentucky-winter cold, the kind of cold that makes you feel like you're freezing from the inside out, the kind of cold that makes you feel like you'll never be warm again. I had no music in me then, just sounds, the shrill noise the back door made when it creaked open, the funny grunts my little brother Lloyd made while we slept together, the tight, muffled squeals that rats made when the rat traps snapped them in half. My grandmother did not believe in wasting anything. She had nothing to waste. She cooked whatever she could get her hands on. Mustard greens, okra, possum, chickens, and rats, and me and Lloyd ate them all. We ate the fried rats because we were nine and seven years old and we did what we were told. We ate them because my grandma could cook them well. But most of all, we ate them because that's all there was to eat.

My mother had gone away sick one day and she never came back. That's all we knew. That's all my father told us. "She's gone away sick and she'll be back soon," was what he said, but "soon" turned into months and years, so the two of us had left Chicago and gone to Louisville to stay with Grandma. Laying in bed at night in my grandma's house, I could remember the night before my mother left us. We were downstairs in the living room back home in South Side Chicago during the Depression, Lloyd and Daddy and me, and we heard a crash and the noise of a window breaking, and we ran upstairs and I felt the rush of cold air and saw my mother at the broken window looking out into the street. She was wearing only a housedress, standing in the freezing nighttime air, the snow blowing in on her face, and she was singing, "Ohh, ohh, ohh, ohh--oh, somebody touched me and it must have been the hand of the Lord."

As a young boy, I thought it was odd for my mother to sing out the window. She played piano and sang in church, but my mother was a private woman, solid and proper. She never spoke out of turn like that. She did not like loud things or loud people, but her behavior had become more and more strange. She had frequent fainting spells. She would yell at us for no reason. She quoted the Bible and scribbled notes endlessly. The lines around her eyes seemed to grow tighter and tighter every day. Her angry outbursts were crushing affairs, sometimes lasting for days.

My daddy never knew what to do when my mother had spells like this. He was not a complicated man. He was a carpenter for the Jones Boys, the black gangsters who ran the ghetto back in Chicago -- the policy rackets, the Jones five-and-dime stores -- the V and X, as they were known in the 'hood. When my Aunt Mabel asked him once why he worked for hoods and hustlers, he made a funny face and said, "Gangsters need carpenters, too. They're no worse than the gangsters who won't give me jobs." He grew up in Lake City, South Carolina, so I was told, but to be honest I never knew exactly where he was really from. I'd heard his father was a white man-- either Irish or Welsh-- who had killed somebody, and Daddy had to get out of the South because of this, which made as much sense as anything else in my life, because since my mother left us, nothing seemed solid except the black space in my stomach. Daddy was a quiet man, with smooth straight hair, soft brown eyes, and firm face. His shoulders were broad, his arms were thick and muscled, and his hands were gigantic, huge iron fists with fingers as thick as cigars. He'd been a catcher with the Metropolitan Baptist Church team in the Negro Leagues -- he even caught the great Satchel Paige once -- and all those years of catching baseballs with a thin mitt had smashed his fingers and made them flat and crooked. He could bend the first knuckle of each hand and hold them out like claws. His fingers were so strong that he could make a circle with his forefinger and thumb and pop you upside the head so hard it felt like a bullet smashing through your skin. My brother and I called that "the Thump Bump," and when he thumped you, it stung for hours.

He tried to talk to my mother as she stood by the window singing. He said, "Get ahold of yourself, Sarah," but she ignored him and kept singing, so he turned away and went downstairs. As he swept past me I heard him mutter something, so I ran to my mother and told her what he said: "Daddy's gonna send you away," I said, but she didn't hear me. She stood with her back to me, staring out the window, and the next morning my daddy came back upstairs with two ambulance attendants in white and one of them said, "Mrs. Jones, you wanna come get your luggage and things?"

She looked over at him without a word, so he said, "Either you come or we'll carry you."

She said, "Can I take my Bible?"

He said, "You can take it."

She slowly picked up her Bible, then suddenly darted for the door to escape, but the two men grabbed her and threw her down on the bed, spread-eagled. She kicked and screamed as they threw a straightjacket on her and carried her out. We followed her downstairs and sat on the steps. Lucy Jackson held Lloyd on her lap and covered his eyes with her hands. I sat next to them, crying, and covered my eyes too, singing the same song, "Ohh, ohh, ohh, ohh -- oh, somebody touched me and it must have been the hand of the Lord." And just like that she was gone -- for days, weeks, months, who knows how long. Soon after, my daddy packed us up and the three of us headed to St. Louis to stay with relatives, then back to Chicago, then back to St. Louis again, till Daddy finally gave up and took us to Louisville to stay with his mother. Then he left.

We didn't hate it in Louisville. We didn't like it either. My grandma's house was a shotgun shack near the Ohio River with no electricity. We drew our water from a well in her backyard. We got our heat from a black potbellied coal stove. We used kerosene lamps and bathed in a big tin washtub. We slept in the kitchen on a cot next to the back door, which was held closed with a rusty bent nail. When the door was closed in the daytime, you could see daylight all around the doorframe. At night we slept with socks on our hands and feet so the rats wouldn't nibble our fingers and toes. In the wintertime, the floor was frozen and wet in the morning. In summer, it was like fire and the smell of old pee stung my nostrils constantly. Breakfast was grits, lunch was nonexistent, and dinner was whatever my grandmother would find that would fry. The teachers at the Samuel T. Coleridge Colored School wanted to make examples of us as strangers and would march Lloyd and me to the back of the classroom every morning and make us take our shoes off and scrub the dirt off our feet and faces with commercial Lifebuoy soap while the other kids cackled. We had no hot water for washing. They seemed to have no idea who we were. My grandmother didn't understand the 1940 Jefferson County school system either, only the notion that we had to go there. Grandma was a proud, strong woman, a former slave; she was thin, rangy, coal-black, wise, and old. She had African beliefs, like hanging asafetida, a horrid-smelling gumlike bark-and-garlic concoction, on a string around our necks to ward off colds, fever, and bad spirits. She led us to the Baptist church every Sunday and spoke in a tongue that me and Lloyd could barely understand. She had been born a slave and used African words we never heard of, like "mwena" for "kids." She'd say, "Mwena, come over here and lift this tub," or "Mwena, go down yonder to the river and catch me some rats." She told us that the more the rats wiggle their tails, the better they'd taste, so we'd wait by the river, snatch up the biggest ones we could find by the tail, and stuff them in a burlap sack. We were free to roam in Kentucky, that part we liked, but at night it was cold and lonely in that dark shotgun shack and it was too much for me, because I wanted my parents. I was mad at them both, but more mad at my daddy, because he was the one who kept it together. Daddy was the one who was solid. Daddy was the one who said we'd always be together. My brother Lloyd, 16 1/2 months younger than me, would cry at night for his daddy, and one night as we lay in bed, he asked, "Did Daddy go away 'cause he's mad at us?"

"Stop whining," I said. "He'll be back." I had a faint recollection of Daddy promising to come back, but I wasn't sure. He'd been gone a long time. We'd been there a year. Nothing seemed certain.

"I didn't hear him sayin' nothin' about coming back," Lloyd said.

"He'll be back," I said.

"Well, if he's coming back, he oughta come on them."

"Who needs him anyway?" I said. "Stop crying' like a kindygarden baby." But deep inside I was scared and nervous, and each night I fell asleep with my teeth chattering from cold and my heart buried someplace near my feet, until that winter night in 1941 when I heard the back door creak open and I saw a huge shadow blocking the entrance, the breath coming from his mouth in clouds as he moved inside, lit a kerosene lamp, which Grandma called coal oil, and sat down, sighing. My fear and anger dissipated like water as me and Lloyd scrambled out of the bed and landed in his lap.

"You promise me you won't go away and leave us no more," I sobbed. "Promise."

"I promise." My daddy said. And he kept his word.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"An appealingly convivial blur of deal-making celebrity anecdotes and professional comebacks...Jones is so open that he seems transparent: You can see a whole world of popular music in him."

--The New Yorker

"Jones's richly anecdotal autobiography...is a well-orchestrated memoir."

--People

--The New Yorker

"Jones's richly anecdotal autobiography...is a well-orchestrated memoir."

--People