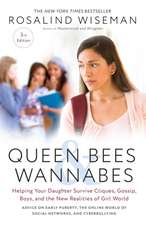

Queen Bee Moms & Kingpin Dads: Dealing with the Difficult Parents in Your Child's Life

Autor Rosalind Wiseman Elizabeth Rapoporten Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2006

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Books for a Better Life (2006)

Even the most well-adjusted moms and dads can experience peer pressure and conflicts with other adults that make them act like they’re back in seventh grade. In Queen Bee Moms & Kingpin Dads, Rosalind Wiseman gives us the tools to handle difficult situations involving teachers and other parents with grace. Reassuring, funny, and unfailingly honest, Wiseman reveals:

• Why PTA meetings and Back-to-School nights tap into parents’ deepest insecurities

• How to recognize the archetypal moms and dads—from Caveman Dad to Hovercraft Mom

• How and when to step in and step out of your child’s conflicts with other children, parents, teachers, or coaches

• How to interpret the code phrases other parents use to avoid (or provoke) confrontation

• Why too many well-meaning dads sit on the sidelines, and how vital it is that they step up to the plate

• What to do and say when the playing field becomes an arena for people to bully and dominate other kids and adults

• How to have respectful yet honest conversations with other parents about sex and drugs when your values are in conflict

• How the way you handle parties, risky behavior, and academic performance affects your child

• How unspoken assumptions about race, religion, and other hot-button subjects sabotage parents’ ability to work together

Queen Bee Moms & Kingpin Dads is filled with the kind of true stories that made Wiseman’s New York Times bestselling book Queen Bees & Wannabes impossible to put down. There are tales of hardworking parents with whom any of us can identify, along with tales of outrageously bad parents—the kind we all have to reckon with. For instance, what do you do when parents donate a large sum of money to a school and their child is promptly transferred into the honors program–while your son with better grades doesn’t make the cut? What about the mother who helps her daughter compose poison-pen e-mails to yours? And what do you say to the parent-coach who screams at your child when the team is losing? Wiseman offers practical advice on avoiding the most common parenting “land mines” and useful scripts to help you navigate difficult but necessary conversations.

Queen Bee Moms & Kingpin Dads is essential reading for parents today. It offers us the tools to become wiser, more relaxed parents–and the inspiration to speak out, act according to our values, show humility, and set the kind of example that will make a real difference in our children’s lives.

Also available as a Random House AudioBook and as an eBook

Preț: 108.50 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 163

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.77€ • 21.60$ • 17.38£

20.77€ • 21.60$ • 17.38£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 22 februarie-08 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400083015

ISBN-10: 140008301X

Pagini: 339

Ilustrații: 4 GRAPHS

Dimensiuni: 134 x 202 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 140008301X

Pagini: 339

Ilustrații: 4 GRAPHS

Dimensiuni: 134 x 202 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

Rosalind Wiseman is a cofounder of the Empower Program, a nonprofit organization that empowers youth to stop violence, and the author of the New York Times bestselling Queen Bees & Wannabes, the basis for the movie Mean Girls. She lives in Washington, D.C., with her husband and two children. Readers can visit her website at rosalindwiseman.com.

Elizabeth Rapoport was the editor of Rosalind Wiseman’s Queen Bees & Wannabes. A full-time editor, writer, and life coach, she lives in White Plains, New York, with her husband and their two teenagers.

From the Hardcover edition.

Elizabeth Rapoport was the editor of Rosalind Wiseman’s Queen Bees & Wannabes. A full-time editor, writer, and life coach, she lives in White Plains, New York, with her husband and their two teenagers.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Perfect Parent World, Land of Perpetual Judgment

"You couldn't pay me enough to go back to seventh grade."

People love to tell me this. Teachers, parents, counselors, principals, people on the street, people at parties--everywhere I go, people tell me that they shudder at the thought of waking up one day transported back to seventh grade. But when I tell them I'm writing a book on parents' social competition, their eyes grow wide with delight or dismay--and always with recognition. "Do I have a story for you," they say conspiratorially. Clearly, few of us have left seventh grade completely behind.

My goal in this book is to get you to do exactly what almost no one wants to do: Go back to seventh grade and understand how the lessons you learned as a child and adolescent affect the way you parent. And when I say "parent," I'm not just referring to your relationship with your child. I'm including in my definition of parenting your interactions and relationships with other parents, teachers, coaches, school administrators, and children other than yours--any other person in your child's world.

You leave your adolescence with a sigh of relief--you think you never have to revisit it--but you're mistaken. You don't just relive it through your children; you also have countless opportunities to experience it all over again as a parent. These are the moments of growth that we all dread so much: You think you've gotten past your adolescent insecurities, but then you have kids and all your emotional maturity flies right out the window. Of course, parenting can bring out the best in us--but we also have to admit that it can sometimes bring out the worst. At the root of our actions lies a deep-seated need to belong. Let's take a closer look at this need.

Back-to-School Night: Night Out or Nightmare?

Let's review the rite of passage I mentioned in the Introduction: Back-to-School Night. I asked parents to tell me how they felt about that night, and you'd be hard-pressed to tell some of their responses apart from those of seventh graders.

Do Parents Worry About How They Look?

You want to look put together because you're going to see a lot of people you know.Virginia, middle school mom

I got dressed up to the nines but one step down because I didn't want to look like I tried too hard.Don, middle school dad

I don't need to dress up for Back-to-School Night because I work.

Alex, middle school mom (oblivious to

the fact that she was dressed in her power suit)

Do Parents Worry About Running into Other Parents?

My daughter was in a special-needs class and I was apprehensive because I thought everyone would know she was the one who needs the extra help. I was embarrassed or ashamed that somehow it was a reflection on me as being a bad parent.Jose, middle school dad

Do Parents Worry About Whether They'll Fit In?

What sticks out is how uncomfortable I felt. The teacher asked if there were any questions and I had one, but I didn't ask because I was worried that people would think I was an inattentive father.

Ronald, middle school dad

I walked into the school and everyone else knew each other--except for me. I just leaned against the wall and thought, "I'm sunk."

Arlene, elementary and middle school mom

While there are parents who eagerly attend Back-to-School Night, most parents admitted to having some degree of anxiety about it. What's behind this discomfort? You've probably already intuited part of the answer: You feel like you're back in middle school. It's clear who's at the top of the social ladder, who's not, and who's waiting to climb up from the lower rungs. You probably have one of two reactions to the scene: You want to be part of it, you hope highly placed, or you want to have nothing to do with it.

Everyone wants to belong somewhere. There's nothing weak or pathological about it--it's a universal drive. It's just that our true character (individually and collectively) is revealed in the moments when that belonging comes at the cost of what we believe in and what we know is right, whether we're thirteen, thirty-three, fifty-three, or seventy-three. To my mind, becoming an adult is the process of understanding and holding on to our sense of self in the face of this drive, because belonging often comes at the cost of the values we stand for.

What groups do we want to belong to? Do those groups accept us? Why or why not? How do we decide where we want to belong? How do boys and girls, men and women attain and maintain respect in their community and in our culture? In turn, how is a social pecking order established through this process?

Writing this book has made me realize that there are many adults who feel just as trapped by the groups they are in, if not more so, than the teens with whom I work. Most parents become friends with other parents beginning in their children's play groups and then continue on through their car pools, athletic teams, and religious youth groups. To be sure, many people develop lifelong friends with people they've met through their children. But there are a lot of parents who are wondering how they became friends with these people and who can't wait for their kids to graduate so they and the other parents can quietly go their separate ways. Why? We chose to be with them on the assumption that we have similar values and because we've gone through similar experiences or rites of passage. But as we pass through parenting's rites of passage, it's easy to confuse partners in arms in a given situation or phase with people with whom we truly want to go through life and can depend on.

How do we know what we're looking for in each other? Let's start by looking at two definitions of culture: the one in Webster's dictionary and my own.

Webster's definition: The customary beliefs, social forms, and material traits of a racial, religious, or social group.

My definition: Everything we "know" about the way the world works but have never been taught.

Our culture makes us feel that we have to be and look a certain way so that we belong--regardless of whether we are poor, wealthy, or anywhere in between. It convinces us that we are "less than" unless we participate in the relentless struggle to keep up with or have more than our neighbors. But our culture is not a thing that happens to us. We are the ones who create and sustain it. If cultural values are handed down through generations, it's because we absorb them and act on them without question. Often we don't even realize the degree to which we're constantly pressuring each other to conform to cultural norms. Primed by these powerful cultural messages--in magazines, on television, in movies, in supermarket conversations, from our own parents--we can trick ourselves into believing that there's just one party to go to, one group to belong to, and that if we don't get in and stay in, we don't measure up or risk being thrown out.

As parents, we understand that the culture has great power over our children; they see the latest ad campaign for jeans and are convinced that their lives would be better if they bought them. However, we may not realize that we're no less immune. If you have a car, ask yourself what it says about you. In full, embarrassing disclosure, I bought an SUV because I couldn't tolerate the image of driving a minivan--which would have been a much better choice because they're cheaper and more fuel-efficient.

We also belong to microcultures where there are similar unwritten rules we "just know" we have to follow. Your children's school, your religious institution, your family--all have unwritten rules you must follow to be accepted, and there are penalties for the people who break those rules.

Cultural rule breakers can make others extremely uncomfortable, so most people don't want them around. These people are seen as "other," possibly tolerated but rarely accepted. Very often, rule breakers aren't respected, their opinions and experiences are easily dismissed, and other people don't want to be seen as associated with them, even when they think the rule breakers are right. If we grow up without learning to question the culture, we take a few lessons with us from our youth:

1. You should please the person who has the most power.

2. You should maintain relationships with the people in power.

3. The result of all this pleasing and maintenance will be that you won't say what you need or want.

4. Loyalty is defined as backing up your friends by saying nothing, laughing, or even joining in when their actions are unethical or cruel.

5. You should be silent in the face of cruelty so that the cruelty isn't turned on you.

So how does this affect parents? I think there is a parent culture that takes its cues from the overall culture, tricking us into thinking there is one best, most desirable way to be a parent. I call it Perfect Parent World.

Welcome to Perfect Parent World

In Perfect Parent World, the kids are perfect. They do their homework without nagging, effortlessly get into all the honors classes, get elected to class offices, and give their parents a steady stream of bragging rights based on their scholastic and athletic accomplishments. In this mythical kingdom, the parents are perfect, too. They're financially stable, wear the right clothes, drive the right cars, never crack under the strain of car pool, offer our peers excellent parenting advice, and have great kids whose pockets are never filled with bad report cards, cigarettes, or Ecstasy.

Our family doesn't do average.

Tammy, mother of a five-year-old, complaining because her

son got an E for "excellent" instead of an O for "outstanding"

No one I know actually resides in Perfect Parent World, but most parents I've met--myself included--measure themselves against this impossible standard, and we imagine that the moms and dads with the most power and highest social status occupy that cherished real estate. But who decides who personifies perfection?

One of the primary ways both boys and girls and men and women define who has power and social status is by how our culture defines masculinity and femininity. Girls and boys are introduced to these cultural constructions very early in life. In middle school and high school they build groups based on how closely they perceive their fit into those cultural constructions, which I call Girl World and Boy World.

To understand more about how Girl World and Boy World evolve into their adult parallels, Mom World and Dad World, let's look at three definitions of the word femininity--the dictionary's, girls', and parents'.

Dictionary definition: The quality or nature of the female sex.

Girl World definition: You have a great body, guys like you, you're not a prude but you're not a slut, you're in control, and you're smart enough to get people to do what you want--preferably without them noticing.

Mom World definition: You have a relationship with a man, are thin, never had any doubts about having children, and are on top of all your thank-you notes.

Now let's look at how the same three sources define masculinity.

Masculinity: The qualities appropriate to, or usually associated with a man, or forming the formal, active, or generative principle of the cosmos. [I swear, my dictionary said this!]

Boy World: You control your friends with a look or a "hey." You effortlessly have the right style and a great body (if it's not effortless or you think too much about it, you'll be accused of being gay), you can laugh off emotional and physical pain, the right girls like you and you like all attention girls give you, you're competitive about everything, and by five years of age you can discuss professional sports with authority (although it's permissible to trade knowledge of sports for expertise in martial arts or cars).

Dad World: You make lots of money and never worry about the money you spend, you're married and have a good relationship with your wife and kids, if you have a lawn it looks like a baseball diamond, you can fix things, and you're in shape but not too much in shape (because then you look like you're trying too hard), and you have a good sense of humor.

Act Like a Woman: Mommy's Little Girl Grows Up

When I work with girls, I explain my definition of culture and then I ask them what they think the culture is trying to persuade them they need to be and look like and what the culture says they shouldn't be. Then I ask them how a girl in their school earns high social status or low social status. I write their answers in for them as the "Act Like a Woman" box.

What the girls realize is that their answers about what the culture wants and doesn't want them to be often mirrors the "Act Like a Woman" box they've said exists in their own community.

Now let's compare the girls' answers with the answers mothers told me when I asked them the same question--but directed to them.

As I talked to mothers, it became clear that the unwritten rules were way too extensive for me to do them justice with a box. So here they are in full.

The "Act Like a Mom" Checklist

*She has the right style. She's cute. She stays on top of the latest trends but she's not too sexy.

*She's thin (no matter how many pregnancies).

*She's athletic (five extra points if that includes tennis).

*She's married to a caring, wonderful, wealthy, communicative, handsome man who always treats her like a queen.

*She's always loved having kids (no moments of hating them allowed) and her kids love her.

*She has lots of friends.

*She's involved in the community and is always available for a few more volunteer activities.

*She loves the family pets (no matter how much they shed because the house magically gets rid of all pet hair).

*She has a clean and organized house.

*She drives a family-friendly station wagon, minivan, or SUV that's immaculately clean, no sticky food allowed.

*She's cheerful, not hysterical and anxious.

*She's cooperative.

*She has great skin--no wrinkles, pimples, or the dreaded combination of both.

*She appears to achieve all of the above effortlessly.

Are you simultaneously laughing, cringing, and resentful? Me too. And just as girls know they're held to an impossible standard of beauty but chase that ideal anyway, mothers know that this ideal is ridiculous but still stay up until 2 a.m. baking cookies for a bake sale instead of buying them on the way to school.

"You couldn't pay me enough to go back to seventh grade."

People love to tell me this. Teachers, parents, counselors, principals, people on the street, people at parties--everywhere I go, people tell me that they shudder at the thought of waking up one day transported back to seventh grade. But when I tell them I'm writing a book on parents' social competition, their eyes grow wide with delight or dismay--and always with recognition. "Do I have a story for you," they say conspiratorially. Clearly, few of us have left seventh grade completely behind.

My goal in this book is to get you to do exactly what almost no one wants to do: Go back to seventh grade and understand how the lessons you learned as a child and adolescent affect the way you parent. And when I say "parent," I'm not just referring to your relationship with your child. I'm including in my definition of parenting your interactions and relationships with other parents, teachers, coaches, school administrators, and children other than yours--any other person in your child's world.

You leave your adolescence with a sigh of relief--you think you never have to revisit it--but you're mistaken. You don't just relive it through your children; you also have countless opportunities to experience it all over again as a parent. These are the moments of growth that we all dread so much: You think you've gotten past your adolescent insecurities, but then you have kids and all your emotional maturity flies right out the window. Of course, parenting can bring out the best in us--but we also have to admit that it can sometimes bring out the worst. At the root of our actions lies a deep-seated need to belong. Let's take a closer look at this need.

Back-to-School Night: Night Out or Nightmare?

Let's review the rite of passage I mentioned in the Introduction: Back-to-School Night. I asked parents to tell me how they felt about that night, and you'd be hard-pressed to tell some of their responses apart from those of seventh graders.

Do Parents Worry About How They Look?

You want to look put together because you're going to see a lot of people you know.Virginia, middle school mom

I got dressed up to the nines but one step down because I didn't want to look like I tried too hard.Don, middle school dad

I don't need to dress up for Back-to-School Night because I work.

Alex, middle school mom (oblivious to

the fact that she was dressed in her power suit)

Do Parents Worry About Running into Other Parents?

My daughter was in a special-needs class and I was apprehensive because I thought everyone would know she was the one who needs the extra help. I was embarrassed or ashamed that somehow it was a reflection on me as being a bad parent.Jose, middle school dad

Do Parents Worry About Whether They'll Fit In?

What sticks out is how uncomfortable I felt. The teacher asked if there were any questions and I had one, but I didn't ask because I was worried that people would think I was an inattentive father.

Ronald, middle school dad

I walked into the school and everyone else knew each other--except for me. I just leaned against the wall and thought, "I'm sunk."

Arlene, elementary and middle school mom

While there are parents who eagerly attend Back-to-School Night, most parents admitted to having some degree of anxiety about it. What's behind this discomfort? You've probably already intuited part of the answer: You feel like you're back in middle school. It's clear who's at the top of the social ladder, who's not, and who's waiting to climb up from the lower rungs. You probably have one of two reactions to the scene: You want to be part of it, you hope highly placed, or you want to have nothing to do with it.

Everyone wants to belong somewhere. There's nothing weak or pathological about it--it's a universal drive. It's just that our true character (individually and collectively) is revealed in the moments when that belonging comes at the cost of what we believe in and what we know is right, whether we're thirteen, thirty-three, fifty-three, or seventy-three. To my mind, becoming an adult is the process of understanding and holding on to our sense of self in the face of this drive, because belonging often comes at the cost of the values we stand for.

What groups do we want to belong to? Do those groups accept us? Why or why not? How do we decide where we want to belong? How do boys and girls, men and women attain and maintain respect in their community and in our culture? In turn, how is a social pecking order established through this process?

Writing this book has made me realize that there are many adults who feel just as trapped by the groups they are in, if not more so, than the teens with whom I work. Most parents become friends with other parents beginning in their children's play groups and then continue on through their car pools, athletic teams, and religious youth groups. To be sure, many people develop lifelong friends with people they've met through their children. But there are a lot of parents who are wondering how they became friends with these people and who can't wait for their kids to graduate so they and the other parents can quietly go their separate ways. Why? We chose to be with them on the assumption that we have similar values and because we've gone through similar experiences or rites of passage. But as we pass through parenting's rites of passage, it's easy to confuse partners in arms in a given situation or phase with people with whom we truly want to go through life and can depend on.

How do we know what we're looking for in each other? Let's start by looking at two definitions of culture: the one in Webster's dictionary and my own.

Webster's definition: The customary beliefs, social forms, and material traits of a racial, religious, or social group.

My definition: Everything we "know" about the way the world works but have never been taught.

Our culture makes us feel that we have to be and look a certain way so that we belong--regardless of whether we are poor, wealthy, or anywhere in between. It convinces us that we are "less than" unless we participate in the relentless struggle to keep up with or have more than our neighbors. But our culture is not a thing that happens to us. We are the ones who create and sustain it. If cultural values are handed down through generations, it's because we absorb them and act on them without question. Often we don't even realize the degree to which we're constantly pressuring each other to conform to cultural norms. Primed by these powerful cultural messages--in magazines, on television, in movies, in supermarket conversations, from our own parents--we can trick ourselves into believing that there's just one party to go to, one group to belong to, and that if we don't get in and stay in, we don't measure up or risk being thrown out.

As parents, we understand that the culture has great power over our children; they see the latest ad campaign for jeans and are convinced that their lives would be better if they bought them. However, we may not realize that we're no less immune. If you have a car, ask yourself what it says about you. In full, embarrassing disclosure, I bought an SUV because I couldn't tolerate the image of driving a minivan--which would have been a much better choice because they're cheaper and more fuel-efficient.

We also belong to microcultures where there are similar unwritten rules we "just know" we have to follow. Your children's school, your religious institution, your family--all have unwritten rules you must follow to be accepted, and there are penalties for the people who break those rules.

Cultural rule breakers can make others extremely uncomfortable, so most people don't want them around. These people are seen as "other," possibly tolerated but rarely accepted. Very often, rule breakers aren't respected, their opinions and experiences are easily dismissed, and other people don't want to be seen as associated with them, even when they think the rule breakers are right. If we grow up without learning to question the culture, we take a few lessons with us from our youth:

1. You should please the person who has the most power.

2. You should maintain relationships with the people in power.

3. The result of all this pleasing and maintenance will be that you won't say what you need or want.

4. Loyalty is defined as backing up your friends by saying nothing, laughing, or even joining in when their actions are unethical or cruel.

5. You should be silent in the face of cruelty so that the cruelty isn't turned on you.

So how does this affect parents? I think there is a parent culture that takes its cues from the overall culture, tricking us into thinking there is one best, most desirable way to be a parent. I call it Perfect Parent World.

Welcome to Perfect Parent World

In Perfect Parent World, the kids are perfect. They do their homework without nagging, effortlessly get into all the honors classes, get elected to class offices, and give their parents a steady stream of bragging rights based on their scholastic and athletic accomplishments. In this mythical kingdom, the parents are perfect, too. They're financially stable, wear the right clothes, drive the right cars, never crack under the strain of car pool, offer our peers excellent parenting advice, and have great kids whose pockets are never filled with bad report cards, cigarettes, or Ecstasy.

Our family doesn't do average.

Tammy, mother of a five-year-old, complaining because her

son got an E for "excellent" instead of an O for "outstanding"

No one I know actually resides in Perfect Parent World, but most parents I've met--myself included--measure themselves against this impossible standard, and we imagine that the moms and dads with the most power and highest social status occupy that cherished real estate. But who decides who personifies perfection?

One of the primary ways both boys and girls and men and women define who has power and social status is by how our culture defines masculinity and femininity. Girls and boys are introduced to these cultural constructions very early in life. In middle school and high school they build groups based on how closely they perceive their fit into those cultural constructions, which I call Girl World and Boy World.

To understand more about how Girl World and Boy World evolve into their adult parallels, Mom World and Dad World, let's look at three definitions of the word femininity--the dictionary's, girls', and parents'.

Dictionary definition: The quality or nature of the female sex.

Girl World definition: You have a great body, guys like you, you're not a prude but you're not a slut, you're in control, and you're smart enough to get people to do what you want--preferably without them noticing.

Mom World definition: You have a relationship with a man, are thin, never had any doubts about having children, and are on top of all your thank-you notes.

Now let's look at how the same three sources define masculinity.

Masculinity: The qualities appropriate to, or usually associated with a man, or forming the formal, active, or generative principle of the cosmos. [I swear, my dictionary said this!]

Boy World: You control your friends with a look or a "hey." You effortlessly have the right style and a great body (if it's not effortless or you think too much about it, you'll be accused of being gay), you can laugh off emotional and physical pain, the right girls like you and you like all attention girls give you, you're competitive about everything, and by five years of age you can discuss professional sports with authority (although it's permissible to trade knowledge of sports for expertise in martial arts or cars).

Dad World: You make lots of money and never worry about the money you spend, you're married and have a good relationship with your wife and kids, if you have a lawn it looks like a baseball diamond, you can fix things, and you're in shape but not too much in shape (because then you look like you're trying too hard), and you have a good sense of humor.

Act Like a Woman: Mommy's Little Girl Grows Up

When I work with girls, I explain my definition of culture and then I ask them what they think the culture is trying to persuade them they need to be and look like and what the culture says they shouldn't be. Then I ask them how a girl in their school earns high social status or low social status. I write their answers in for them as the "Act Like a Woman" box.

What the girls realize is that their answers about what the culture wants and doesn't want them to be often mirrors the "Act Like a Woman" box they've said exists in their own community.

Now let's compare the girls' answers with the answers mothers told me when I asked them the same question--but directed to them.

As I talked to mothers, it became clear that the unwritten rules were way too extensive for me to do them justice with a box. So here they are in full.

The "Act Like a Mom" Checklist

*She has the right style. She's cute. She stays on top of the latest trends but she's not too sexy.

*She's thin (no matter how many pregnancies).

*She's athletic (five extra points if that includes tennis).

*She's married to a caring, wonderful, wealthy, communicative, handsome man who always treats her like a queen.

*She's always loved having kids (no moments of hating them allowed) and her kids love her.

*She has lots of friends.

*She's involved in the community and is always available for a few more volunteer activities.

*She loves the family pets (no matter how much they shed because the house magically gets rid of all pet hair).

*She has a clean and organized house.

*She drives a family-friendly station wagon, minivan, or SUV that's immaculately clean, no sticky food allowed.

*She's cheerful, not hysterical and anxious.

*She's cooperative.

*She has great skin--no wrinkles, pimples, or the dreaded combination of both.

*She appears to achieve all of the above effortlessly.

Are you simultaneously laughing, cringing, and resentful? Me too. And just as girls know they're held to an impossible standard of beauty but chase that ideal anyway, mothers know that this ideal is ridiculous but still stay up until 2 a.m. baking cookies for a bake sale instead of buying them on the way to school.

Recenzii

"Wise yet practical and full of humor, Queen Bee Moms & Kingpin Dads is a must-read for parents who want to deal with the other adults in their children’s lives with skill and compassion, rather than wrath and confusion. Rosalind Wiseman’s thoughtful suggestions will spare parents endless conflicts and substitute creative interventions. This book forces us to look ourselves in the mirror and face both our strengths and weaknesses while inspiring us to act as strong yet empathic role models for our children in a much-too-pressured and competitive world." —William Pollack, author of Real Boys: Rescuing Our Sons from the Myths of Boyhood

"Rosalind Wiseman is consistently amazing for her window on the real world. As always, she has an uncanny knack for characterizing people whom we see every day, and I found her stories compelling and poignant. Her advice is specific and to the point and can only be extremely helpful to parents taking on the humbling and perplexing world of the other adults who play such a big part in their own kids' lives. Above all, I found the book extraordinarily compassionate." —Anthony Wolf, Ph.D., author of Get Out of My Life, But First Could You Drive Me and Cheryl to the Mall?

“Wise, funny, real, and right on, Queen Bee Moms & Kingpin Dads will be your bible for handling the adults in your child’s life – including yourself – with dignity and grace. Reading this book is an act of courage and love on behalf of your family. —Rachel Simmons, author of Odd Girl Out: The Hidden Culture of Aggression in Girls

"Rosalind Wiseman has a good ear and a good eye. She watches and listens to the every day talk of kids and adults and hears and sees below the surface to identify important underlying social realities. In Queen Bee Moms and Kingpin Dads she provides a road map for parents to help them negotiate the treacherous waters of adult peer culture on behalf of their children and their own peace of mind." —James Garbarino, Ph.D., author of See Jane Hit and Lost Boys

"Queen Bee Moms and Kingpin Dads is honest and wise. As a father, I found the insights, stories and practical information in this book very powerful. As a professional, I found the book's basic premise to be profoundly important to the field of child development. Rosalind Wiseman asks nothing less of us than basic human civility." —Michael Gurian, author of The Minds of Boys and The Wonder of Girls

"Rosalind Wiseman is consistently amazing for her window on the real world. As always, she has an uncanny knack for characterizing people whom we see every day, and I found her stories compelling and poignant. Her advice is specific and to the point and can only be extremely helpful to parents taking on the humbling and perplexing world of the other adults who play such a big part in their own kids' lives. Above all, I found the book extraordinarily compassionate." —Anthony Wolf, Ph.D., author of Get Out of My Life, But First Could You Drive Me and Cheryl to the Mall?

“Wise, funny, real, and right on, Queen Bee Moms & Kingpin Dads will be your bible for handling the adults in your child’s life – including yourself – with dignity and grace. Reading this book is an act of courage and love on behalf of your family. —Rachel Simmons, author of Odd Girl Out: The Hidden Culture of Aggression in Girls

"Rosalind Wiseman has a good ear and a good eye. She watches and listens to the every day talk of kids and adults and hears and sees below the surface to identify important underlying social realities. In Queen Bee Moms and Kingpin Dads she provides a road map for parents to help them negotiate the treacherous waters of adult peer culture on behalf of their children and their own peace of mind." —James Garbarino, Ph.D., author of See Jane Hit and Lost Boys

"Queen Bee Moms and Kingpin Dads is honest and wise. As a father, I found the insights, stories and practical information in this book very powerful. As a professional, I found the book's basic premise to be profoundly important to the field of child development. Rosalind Wiseman asks nothing less of us than basic human civility." —Michael Gurian, author of The Minds of Boys and The Wonder of Girls

Descriere

Even the most well-adjusted moms and dads can experience peer pressure and conflicts with other adults that make them act like they're back in seventh grade. In "Queen Bee Moms & Kingpin Dads," Wiseman delivers the tools to handle difficult situations involving teachers and other parents with grace.

Premii

- Books for a Better Life Finalist, 2006