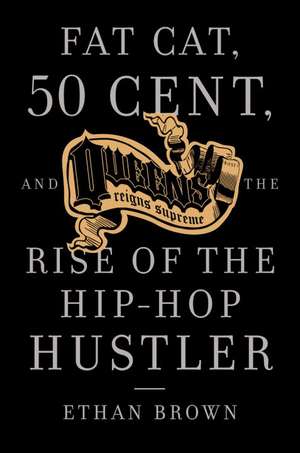

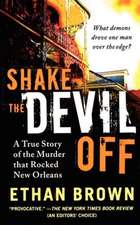

Queens Reigns Supreme: Fat Cat, 50 Cent, and the Rise of the Hip Hop Hustler

Autor Ethan Brownen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2005

For years, rappers from Nas to Ja Rule have hero-worshipped the legendary drug dealers who dominated Queens in the 1980s with their violent crimes and flashy lifestyles. Now, for the first time ever, this gripping narrative digs beneath the hip-hop fables to re-create the rise and fall of hustlers like Lorenzo “Fat Cat” Nichols, Gerald “Prince” Miller, Kenneth “Supreme” McGriff, and Thomas “Tony Montana” Mickens. Spanning twenty-five years, from the violence of the crack era to Run DMC to the infamous murder of NYPD rookie Edward Byrne to Tupac Shakur to 50 Cent’s battles against Ja Rule and Murder Inc., to the killing of Jam Master Jay, Queens Reigns Supreme is the first inside look at the infamous southeast Queens crews and their connections to gangster culture in hip hop today.

Preț: 106.63 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 160

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.40€ • 21.82$ • 17.01£

20.40€ • 21.82$ • 17.01£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-10 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400095230

ISBN-10: 1400095239

Pagini: 239

Ilustrații: 20-PAGE PHOTO SECTION

Dimensiuni: 158 x 233 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Ediția:Anchor Books.

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 1400095239

Pagini: 239

Ilustrații: 20-PAGE PHOTO SECTION

Dimensiuni: 158 x 233 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Ediția:Anchor Books.

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Ethan Brown writes about pop music, crime, and drug policy for publications such as Wired, New York, Rolling Stone, The Village Voice, and GQ. This is his first book. He lives in New York.

Extras

Chapter 1

1

The Crews Coalesce

Southeast Queens lies at the farthest reaches of the borough, on the Long Island border, a neighborhood so far from Manhattan it might as well be another state. With its wide, almost interstate-like boulevards (Rockaway, Sutphin, Baisley, Guy R. Brewer) and its major parkways (Belt and Grand Central), southeast Queens has little in common with the crowded, narrow streets of Manhattan or even with the remote parts of outer boroughs like the Bronx and Brooklyn.

Though the area is just one small corner of the most middle-class, most immigrant-populated borough, it’s not considered a single, unified neighborhood by anyone who lives there. No one says they’re from “southeast Queens.” This isn’t a matter of pride. The area comprises a series of interlocking neighborhoods, each one distinct to its natives. Southeast Queens is home to some of the most sprawling housing projects in all of New York City, most prominently South Jamaica’s Baisley Park Houses and the South Jamaica Houses, nicknamed the “40 Projects” because its cluster of tall brick buildings sits beside Public School 40. South Jamaica is composed mostly of public housing though one area, Jamaica Estates, is dominated by the middle class and is the birthplace of Donald Trump. Further to the south are the Springfield Gardens and Laurelton sections of southeast Queens, which are made up of blocks of middle-class housing developments that breed a professional class of doctors, lawyers, and accountants.

Then there is Hollis. Located just east of South Jamaica, the single-family homes of Hollis have for decades been a refuge for lower-middle-class African Americans fleeing the cramped conditions of poor neighborhoods such as the South Bronx and Harlem. Colin Powell’s parents bought their first home, a three-bedroom bungalow at 183-68 Elmira Avenue, for $17,500. The neighborhood, Powell wrote in his autobiography My American Journey, “carried a certain cachet, a cut above Jamaica, Queens and just below St. Albans, then another gold coast for middle class blacks.” Powell’s African-American neighbors no doubt shared his lofty sentiments about Hollis; though many of the homes in the area were modest, single-level units, most had ample front and backyards and even basements, a rarity in inner-city neighborhoods, even in the outer boroughs. In Hollis, residents could feel like they were part of a neighborhood but could keep their distance whenever they needed to, just like in the suburbs.

By the mid-seventies, Hollis’s luster began to fade: Spurred by the busing of blacks to white schools and the decay of New York City’s infrastructure, panic selling of homes by whites became commonplace, while gangs like Black Rain and Seven Crowns and drug distribution networks controlled by Mafia families flooded the neighborhood with heroin. Like many urban neighborhoods in America, Hollis had experienced a spike in cocaine use in the early seventies; heroin, however, was a far more dangerous epidemic, creating thousands of addicts and fattening the bottom line of drug organizations.

As the Mafia maintained a monopoly on heroin importation routes (the drugs originated in southeast Asia, were refined in Italy, and then smuggled to the United States), their profits measured in the billions. With the heroin trade, the Mafia had the best of both worlds: Dealers and middlemen were forced to come to them for product so they could be choosy about which distributors they did business with, thus reducing the risk of being infiltrated by informants. On the other end, because there were no competing grades of heroin, customers didn’t complain about heroin that was “stepped on,” or cut with substances like baby powder.

Heroin ultimately ravaged the social fabric of southeast Queens. Addicts were so abundant that senior citizens often shuttered themselves indoors for fear of encountering them. The neighborhood’s rapid descent from small-town peace to inner-city mayhem took even law enforcement by surprise. “It used to be that drug dealers crawled out from under a rock and then went right back under that rock,” explains former Queens Narcotics Detective Michael McGuinness, “but by the early eighties they weren’t going back under the rock anymore.” When dopers weren’t getting a fix on the streets of southeast Queens they were sticking up bodegas or robbing houses (particularly in Hollis) for whatever they could get their hands on: TVs, household appliances, sneakers, even, ironically, guns tucked away in closets or sock drawers that were meant to protect residents from such intruders. Doped-up burglars with a particularly sick of sense of humor (or an acute lack of shame) would often defecate in the toilets of their victims, leaving the foul mess for the homeowner to find.

Trips to the bank or a check-cashing store became treacherous: Dopers grabbed wallets and pocketbooks from customers the moment they walked out the door. When that breed of victim wised up, heroin addicts turned their sights on easier, but less lucrative marks, mugging Hollis teenagers for their coats or shoes. New York City jails soon became crowded with low-level thugs addicted to heroin.

Addicts who remained on the outside fell victim to predatory business practices from dealers. Success in the heroin business often required killing a few customers with too-pure product; instead of having a deterrent effect, overdoses attracted customers drawn to a potent new product. Heroin was a lucrative hustle, but in the rougher, more competitive sections of southeast Queens, dealing could be just as lethal as using. Most drug dealers would beat or slap around rivals, but heroin dealers famously had no qualms about murdering one another.

For those turned off by the violence, there were hustles far less dangerous than heroin in the seventies. Numbers running was a favorite scheme in southeast Queens; since law enforcement sometimes looked the other way from this seemingly victimless crime in return for bribes, numbers parlors flourished in the neighborhood. Numbers shops were run by easygoing, affable businessmen with nicknames like “Grumpy” and “Chop,” entrepreneurs more dedicated to customer service than most owners of bodegas and supermarkets in the neighborhood. Numbers runners set out doughnuts and coffee for gamblers and kept the floors immaculately clean. Best of all, hitting that winning number—the odds were often set at something like 600:1—provided a high no drug could match. (Indeed, the down payment on Colin Powell’s parents’ Hollis home came from proceeds from a winning number.) Mafiosi involved in the heroin trade viewed numbers runners as the most trustworthy guys on the streets. They were also highly attuned to the tastes of their clients; since hundreds of customers went in and out of the parlors, numbers runners had a good sense of the underground economy. How many people were into heroin? Coke? The numbers runners knew, and they helped the Mafia.

Unlike in the safer, more sedate world of numbers, steely nerves were a requirement for success in the dope business. No one personified the fearlessness of heroin hustlers better than Hollis native Ronald “Bumps” Bassett. Unlike his fellow dealers, Bumps didn’t want adulation or notoriety; he was simply out for the cash. When he left his base on Farmers Boulevard in Hollis to hang out at the open-air drug bazaar of 150th Street in South Jamaica all the young hustlers on the block would excitedly cry out “Hey, hey, Ronnie’s over here.” “They paid homage to Ronnie Bumps,” says one former Hollis hustler, “but he didn’t care. He was a man among the boys.” Bumps looked the part, too: With his long mane of straightened hair, pale light brown skin, and reddish birthmark just above his mouth he was a dead ringer for Ron O’Neal, the suave actor who played the cocaine kingpin nicknamed “Priest” in the classic 1972 blaxploitation film Superfly. Bumps was one of the first real icons of the emerging drug business in southeast Queens, and he would have imitators for decades to come.

The nihilism of the dopers and the flashiness of dealers like Ronnie Bumps served as the inspiration for the generation of hustlers who came of age in southeast Queens in the early eighties. Without the experience or organizational skills of the street icons of the seventies, the new breed of mostly teenage hustlers started out small. The White Castle hamburger stand on Hollis Avenue and Francis Lewis Boulevard was robbed almost daily, and a depot for Mister Softee ice cream trucks in Queens Village provided another favorite target. Unsurprisingly, bitter feuds broke out among petty hustlers over the most lucrative marks in southeast Queens, battles that in turn led to the formation of organized crews in the neighborhood. “It became a competition,” remembers one former hustler raised in South Jamaica’s 40 Projects. “You had the guys from Hollis, you had the guys from Southside and then you had the guys from off Linden Boulevard. A lot of dudes from Hollis didn’t like guys from over here because we were in the projects. And the guys from the projects didn’t like the guys from Hollis because they lived in Hollis. It was just animosity.”

The rivalry between Hollis and South Jamaica was typical (in southeast Queens, Hollis is dubbed Northside; South Jamaica, Southside) but it was also based in class. South Jamaica hustlers were mostly poor and uneducated while in Hollis many attended private Catholic schools and went on to college. If Hollis, with its single-family houses and neat lawns, was something of a lower- middle-class paradise, South Jamaica was a lower-class hell of towering brick public housing projects that seemed to block out the sky, abandoned, burnt-out buildings, and desolate stretches of blocks where everyone could feel as though they were alone in the area.

Even among the rough-and-tumble scene of South Jamaica, the hustlers from Linden Boulevard stood out. They were poor—many came from South Jamaica’s Baisley Park Houses—and frighteningly tough. They rushed headlong into fights with guns and knives drawn, sending even those with seasoned street pedigrees fleeing for their lives. “They used to come with guns and knives and all we had was our bare fists and a quarter to call somebody,” remembers the former 40 Projects hustler. “We got into a dispute with those guys in the cafeteria of Andrew Jackson High School and when the fight started we were quickly outnumbered. We barely escaped with our lives.”

There was one more striking difference separating the Linden Boulevard posse from the rest of southeast Queens: religion. Many claimed affiliation with the Five Percent Nation, a splinter sect of the Nation of Islam (NOI) founded in 1963 by minister Clarence Edward Smith, aka Clarence 13X. Smith, whose followers called him Father Allah, rejected the belief that NOI founder Wallace Fard was God (“the black man is God,” he said), and believed that only 5 percent of the world’s population is righteous. “Peace, God” was how Five Percenters greeted each other, earning the Linden Boulevard crew the name the Peace Gods.

1

The Crews Coalesce

Southeast Queens lies at the farthest reaches of the borough, on the Long Island border, a neighborhood so far from Manhattan it might as well be another state. With its wide, almost interstate-like boulevards (Rockaway, Sutphin, Baisley, Guy R. Brewer) and its major parkways (Belt and Grand Central), southeast Queens has little in common with the crowded, narrow streets of Manhattan or even with the remote parts of outer boroughs like the Bronx and Brooklyn.

Though the area is just one small corner of the most middle-class, most immigrant-populated borough, it’s not considered a single, unified neighborhood by anyone who lives there. No one says they’re from “southeast Queens.” This isn’t a matter of pride. The area comprises a series of interlocking neighborhoods, each one distinct to its natives. Southeast Queens is home to some of the most sprawling housing projects in all of New York City, most prominently South Jamaica’s Baisley Park Houses and the South Jamaica Houses, nicknamed the “40 Projects” because its cluster of tall brick buildings sits beside Public School 40. South Jamaica is composed mostly of public housing though one area, Jamaica Estates, is dominated by the middle class and is the birthplace of Donald Trump. Further to the south are the Springfield Gardens and Laurelton sections of southeast Queens, which are made up of blocks of middle-class housing developments that breed a professional class of doctors, lawyers, and accountants.

Then there is Hollis. Located just east of South Jamaica, the single-family homes of Hollis have for decades been a refuge for lower-middle-class African Americans fleeing the cramped conditions of poor neighborhoods such as the South Bronx and Harlem. Colin Powell’s parents bought their first home, a three-bedroom bungalow at 183-68 Elmira Avenue, for $17,500. The neighborhood, Powell wrote in his autobiography My American Journey, “carried a certain cachet, a cut above Jamaica, Queens and just below St. Albans, then another gold coast for middle class blacks.” Powell’s African-American neighbors no doubt shared his lofty sentiments about Hollis; though many of the homes in the area were modest, single-level units, most had ample front and backyards and even basements, a rarity in inner-city neighborhoods, even in the outer boroughs. In Hollis, residents could feel like they were part of a neighborhood but could keep their distance whenever they needed to, just like in the suburbs.

By the mid-seventies, Hollis’s luster began to fade: Spurred by the busing of blacks to white schools and the decay of New York City’s infrastructure, panic selling of homes by whites became commonplace, while gangs like Black Rain and Seven Crowns and drug distribution networks controlled by Mafia families flooded the neighborhood with heroin. Like many urban neighborhoods in America, Hollis had experienced a spike in cocaine use in the early seventies; heroin, however, was a far more dangerous epidemic, creating thousands of addicts and fattening the bottom line of drug organizations.

As the Mafia maintained a monopoly on heroin importation routes (the drugs originated in southeast Asia, were refined in Italy, and then smuggled to the United States), their profits measured in the billions. With the heroin trade, the Mafia had the best of both worlds: Dealers and middlemen were forced to come to them for product so they could be choosy about which distributors they did business with, thus reducing the risk of being infiltrated by informants. On the other end, because there were no competing grades of heroin, customers didn’t complain about heroin that was “stepped on,” or cut with substances like baby powder.

Heroin ultimately ravaged the social fabric of southeast Queens. Addicts were so abundant that senior citizens often shuttered themselves indoors for fear of encountering them. The neighborhood’s rapid descent from small-town peace to inner-city mayhem took even law enforcement by surprise. “It used to be that drug dealers crawled out from under a rock and then went right back under that rock,” explains former Queens Narcotics Detective Michael McGuinness, “but by the early eighties they weren’t going back under the rock anymore.” When dopers weren’t getting a fix on the streets of southeast Queens they were sticking up bodegas or robbing houses (particularly in Hollis) for whatever they could get their hands on: TVs, household appliances, sneakers, even, ironically, guns tucked away in closets or sock drawers that were meant to protect residents from such intruders. Doped-up burglars with a particularly sick of sense of humor (or an acute lack of shame) would often defecate in the toilets of their victims, leaving the foul mess for the homeowner to find.

Trips to the bank or a check-cashing store became treacherous: Dopers grabbed wallets and pocketbooks from customers the moment they walked out the door. When that breed of victim wised up, heroin addicts turned their sights on easier, but less lucrative marks, mugging Hollis teenagers for their coats or shoes. New York City jails soon became crowded with low-level thugs addicted to heroin.

Addicts who remained on the outside fell victim to predatory business practices from dealers. Success in the heroin business often required killing a few customers with too-pure product; instead of having a deterrent effect, overdoses attracted customers drawn to a potent new product. Heroin was a lucrative hustle, but in the rougher, more competitive sections of southeast Queens, dealing could be just as lethal as using. Most drug dealers would beat or slap around rivals, but heroin dealers famously had no qualms about murdering one another.

For those turned off by the violence, there were hustles far less dangerous than heroin in the seventies. Numbers running was a favorite scheme in southeast Queens; since law enforcement sometimes looked the other way from this seemingly victimless crime in return for bribes, numbers parlors flourished in the neighborhood. Numbers shops were run by easygoing, affable businessmen with nicknames like “Grumpy” and “Chop,” entrepreneurs more dedicated to customer service than most owners of bodegas and supermarkets in the neighborhood. Numbers runners set out doughnuts and coffee for gamblers and kept the floors immaculately clean. Best of all, hitting that winning number—the odds were often set at something like 600:1—provided a high no drug could match. (Indeed, the down payment on Colin Powell’s parents’ Hollis home came from proceeds from a winning number.) Mafiosi involved in the heroin trade viewed numbers runners as the most trustworthy guys on the streets. They were also highly attuned to the tastes of their clients; since hundreds of customers went in and out of the parlors, numbers runners had a good sense of the underground economy. How many people were into heroin? Coke? The numbers runners knew, and they helped the Mafia.

Unlike in the safer, more sedate world of numbers, steely nerves were a requirement for success in the dope business. No one personified the fearlessness of heroin hustlers better than Hollis native Ronald “Bumps” Bassett. Unlike his fellow dealers, Bumps didn’t want adulation or notoriety; he was simply out for the cash. When he left his base on Farmers Boulevard in Hollis to hang out at the open-air drug bazaar of 150th Street in South Jamaica all the young hustlers on the block would excitedly cry out “Hey, hey, Ronnie’s over here.” “They paid homage to Ronnie Bumps,” says one former Hollis hustler, “but he didn’t care. He was a man among the boys.” Bumps looked the part, too: With his long mane of straightened hair, pale light brown skin, and reddish birthmark just above his mouth he was a dead ringer for Ron O’Neal, the suave actor who played the cocaine kingpin nicknamed “Priest” in the classic 1972 blaxploitation film Superfly. Bumps was one of the first real icons of the emerging drug business in southeast Queens, and he would have imitators for decades to come.

The nihilism of the dopers and the flashiness of dealers like Ronnie Bumps served as the inspiration for the generation of hustlers who came of age in southeast Queens in the early eighties. Without the experience or organizational skills of the street icons of the seventies, the new breed of mostly teenage hustlers started out small. The White Castle hamburger stand on Hollis Avenue and Francis Lewis Boulevard was robbed almost daily, and a depot for Mister Softee ice cream trucks in Queens Village provided another favorite target. Unsurprisingly, bitter feuds broke out among petty hustlers over the most lucrative marks in southeast Queens, battles that in turn led to the formation of organized crews in the neighborhood. “It became a competition,” remembers one former hustler raised in South Jamaica’s 40 Projects. “You had the guys from Hollis, you had the guys from Southside and then you had the guys from off Linden Boulevard. A lot of dudes from Hollis didn’t like guys from over here because we were in the projects. And the guys from the projects didn’t like the guys from Hollis because they lived in Hollis. It was just animosity.”

The rivalry between Hollis and South Jamaica was typical (in southeast Queens, Hollis is dubbed Northside; South Jamaica, Southside) but it was also based in class. South Jamaica hustlers were mostly poor and uneducated while in Hollis many attended private Catholic schools and went on to college. If Hollis, with its single-family houses and neat lawns, was something of a lower- middle-class paradise, South Jamaica was a lower-class hell of towering brick public housing projects that seemed to block out the sky, abandoned, burnt-out buildings, and desolate stretches of blocks where everyone could feel as though they were alone in the area.

Even among the rough-and-tumble scene of South Jamaica, the hustlers from Linden Boulevard stood out. They were poor—many came from South Jamaica’s Baisley Park Houses—and frighteningly tough. They rushed headlong into fights with guns and knives drawn, sending even those with seasoned street pedigrees fleeing for their lives. “They used to come with guns and knives and all we had was our bare fists and a quarter to call somebody,” remembers the former 40 Projects hustler. “We got into a dispute with those guys in the cafeteria of Andrew Jackson High School and when the fight started we were quickly outnumbered. We barely escaped with our lives.”

There was one more striking difference separating the Linden Boulevard posse from the rest of southeast Queens: religion. Many claimed affiliation with the Five Percent Nation, a splinter sect of the Nation of Islam (NOI) founded in 1963 by minister Clarence Edward Smith, aka Clarence 13X. Smith, whose followers called him Father Allah, rejected the belief that NOI founder Wallace Fard was God (“the black man is God,” he said), and believed that only 5 percent of the world’s population is righteous. “Peace, God” was how Five Percenters greeted each other, earning the Linden Boulevard crew the name the Peace Gods.

Descriere

Brown has the inside scoop on major figures from Russell Simmons to 50 Cent in this unprecedented and exclusive story of the gangster culture in hip hop today.