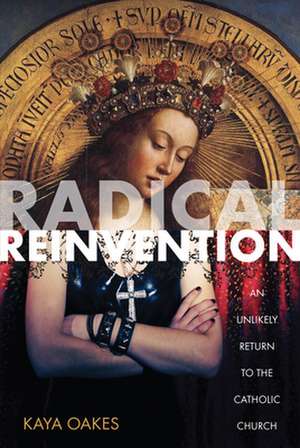

Radical Reinvention: An Unlikely Return to the Catholic Church

Autor Kaya Oakesen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 2012

Preț: 63.84 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 96

Preț estimativ în valută:

12.22€ • 12.74$ • 10.15£

12.22€ • 12.74$ • 10.15£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781593764319

ISBN-10: 1593764316

Pagini: 245

Dimensiuni: 142 x 210 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Counterpoint Press

ISBN-10: 1593764316

Pagini: 245

Dimensiuni: 142 x 210 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Counterpoint Press

Recenzii

Praise for Radical Reinvention

"Oakes not only treats readers to gorgeous prose, but manages to provide an overview and history of the best of the Catholic faith, without losing momentum." —Publishers Weekly (starred review)

"Honestly, humorously, and irreverently recounted... A clarion call for an institution’s radical reinvention." —Booklist

"[An] uneasy entry back into the Catholic church, with plenty of F-bombs thrown in for good effect." —Kirkus

Praise for Slanted and Enchanted

“An impassioned, optimistic case for indie’s vitality that doesn’t assume readers are coming to [the] book already well versed in the subject . . . Fresh and perceptive.” —San Francisco Chronicle

“Oakes is no dry outsider. She believes in what she describes, she contributes to it and she speaks its language.” —The Plain Dealer (Cleveland)

“As an explanation and excavation of the already fading recent past, it is essential reading.” —Publishers Weekly

"Oakes not only treats readers to gorgeous prose, but manages to provide an overview and history of the best of the Catholic faith, without losing momentum." —Publishers Weekly (starred review)

"Honestly, humorously, and irreverently recounted... A clarion call for an institution’s radical reinvention." —Booklist

"[An] uneasy entry back into the Catholic church, with plenty of F-bombs thrown in for good effect." —Kirkus

Praise for Slanted and Enchanted

“An impassioned, optimistic case for indie’s vitality that doesn’t assume readers are coming to [the] book already well versed in the subject . . . Fresh and perceptive.” —San Francisco Chronicle

“Oakes is no dry outsider. She believes in what she describes, she contributes to it and she speaks its language.” —The Plain Dealer (Cleveland)

“As an explanation and excavation of the already fading recent past, it is essential reading.” —Publishers Weekly

Praise for "Radical Reinvention""Oakes not only treats readers to gorgeous prose, but manages to provide an overview and history of the best of the Catholic faith, without losing momentum." --"Publishers Weekly" (starred review)"Honestly, humorously, and irreverently recounted... A clarion call for an institution's radical reinvention." --"Booklist""[An] uneasy entry back into the Catholic church, with plenty of F-bombs thrown in for good effect." --"Kirkus"Praise for "Slanted and Enchanted""An impassioned, optimistic case for indie's vitality that doesn't assume readers are coming to [the] book already well versed in the subject . . . Fresh and perceptive." --San Francisco Chronicle"Oakes is no dry outsider. She believes in what she describes, she contributes to it and she speaks its language." --The Plain Dealer (Cleveland)"As an explanation and excavation of the already fading recent past, it is essential reading." --Publishers Weekly

Notă biografică

Kaya Oakes is the author of Slanted and Enchanted: The Evolution of Indie Culture, the poetry collection Telegraph, and cofounder of Kitchen Sink, winner of the Utne Independent Press Award for Best New Magazine. She teaches at the University of California, Berkeley, and lives in Oakland.

Extras

Prologue

Hell was revealed to me the day I got busted for drawing on my hand with a magic marker. An eighth-grader supervised as I scrubbed my hand in the sink during detention. “I swear to God,” I told this thin-faced blond, “I didn’t mean anything bad.”

“Do you know what happens when you say ‘I swear to God’?” she asked.

I shook my head. I was seven, maybe eight years old.

“When you die, you go straight to hell.”

It was the ’70s and the elderly nuns at my Catholic school no longer wore habits. A group of Moonies had moved into the building next door, which used to be the nuns’ convent when their numbers were higher. Now there were only a few of them left and they shared a small apartment around the block. We were admonished never to speak to the Moonies, who offered us candy during recess. But I was a rotten-toothed candy addict and found it hard to say no to those perpetually smiling Moonies.

“Do you know what happens if you say ‘I swear to the Holy Spirit’?” the eighth grader continued.

Had Mom and Dad ever mentioned this? Dad was always saying “I swear to God.” He also said shit, Jesus fucking Christ, goddamn, hell, fuck, and damnit, sometimes all squashed together after he’d drunk enough wine: shitfuckgoddamnjesuschristhell. What did any of this have to do with the Holy Spirit? The eighth grader leaned closer, looking into my eyes.

“If you ever say ‘I swear to the Holy Spirit’,” she said, pointing at my face, “you’ll go straight to hell without even dying first.”

After detention, I walked home, reached over the fence for the house key, let myself in, walked upstairs to my room, knelt on the floor and whispered, “I swear to the Holy Spirit.” Highly suspicious of her theory, I wanted some empirical evidence to prove that she was right. Nothing happened, unless I’ve been in hell ever since.

A couple of weeks after that detention, one of the nuns told us a story. A little boy was sick and on the verge of death. She showed us a pastel sketch of a red-cheeked, blond boy in a pristine white nightshirt, his eyes rolled toward heaven. He was just about to die when he called out to Jesus to save him. Jesus came in a white robe and laid his hand on the boy’s face. The boy lived.

“Anytime you call out to Jesus, when you’re in danger, he will come and save you,” the nun said.

Recess arrived and I looked down at the asphalt of the playground. Then I took off my glasses, folded them up, and placed them on the ground. I backed up a few paces and broke into a hard sprint. After I’d gotten up as much speed as my chunky legs could manage, I flung myself hard at a swath of asphalt, and, like the dying kid, called out to Jesus. That day, I walked home with brown blood crusting my pebbly wounds. Clearly, I was going to hell. It must have been the marker.

Jesus didn’t give a shit about fat little girls with rat’s nests in their hair, who slept in dirty T-shirts, and drew on their hands. So I became fatter, dirtier, and louder. I answered every rhetorical question in catechism with a sarcastic remark, refused to pray, and rolled my eyes so hard during Mass that people probably thought I was an epileptic. At the end of the school year, my mother insisted that I start attending a public school. The teacher there was an arty single mother who wore aprons and had us throwing pottery in the back of the classroom when we got out of control. Nobody ever talked about God.

The Catholic Church I grew up in may have had its share of Hell, primarily in the form of batshit eighth grade detention monitors, but it also held an appeal for a fifth-generation Bay Area girl. I was born in 1971, and thus am a child of a decade that began in radicalism and ended on the verge of Reaganomics. Vatican II ended in 1965, ushering in a new era in the Church: ecumenicism, a new sense of openness between clergy and lay people, hopes for more progressive reform, and most importantly, Mass in the vernacular instead of Latin.

My Catholic elementary school grappled with the reforms of Vatican II. Although the nuns were pleased to be walking around out of habits, they were awkward in normal clothes. With cropped haircuts, polyester skirt suits grazing their knees, and small crosses hanging around their necks, they looked like peppy grandmothers. In religious studies class, for lack of instructions from the Vatican about new forms of catechism, we made endless God’s eyes, wrapping yarn around popsicle sticks and carrying them home to mothers who already had a line of God’s eyes on the windowsill from previous week’s classes. We crafted tissue-paper collages about Jesus and did skits about saints that often involved someone being martyred for extra credit. My older sister’s high school performed Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar in the same year, and after that I believed that Jesus really wore bell-bottoms and a Superman shirt. Catholicism was a lot of things in the seventies, but from my preadolescent perspective, it was mostly entertaining and slightly absurd.

But the Catholic Church I grew up in was not just about clunky tradition and occasionally dorky catechism: it was about service to others, liberation theology, and the legacy of scholarship used to enlighten the present day. As a child, I never heard Latin in Mass, not even when the priest said the blessing at communion, or sang songs other than the folky hymns that were popularized by groups like the Saint Louis Jesuits, authors of tunes like the soft rock “Earthen Vessels,” which we crooned to the accompaniment of an acoustic guitar. When I made my first confession, instead of heading into a dim closet and sitting behind a screen, I sat in a folding chair on the altar, face to face with the priest, while my classmates giggled and poked one another far back in the pews. It was an experiment called “open confession,” and in my case it totally failed: freaked out with the stage fright that would plague me for the rest of my life, as soon as the priest asked what my sins had been, I started bawling and ran out of the church. But the priest came and found me, apologized for the entire experiment, and excused me from open confession from then on.

My education veered between Catholic grammar school and public elementary school, Catholic high school and alternative learning high school, experimental public college and Catholic college, public graduate school and Catholic graduate school. The Catholic college was mostly a matter of money: my father worked there, and tuition was free. The other changes were based on my teacher mother’s attempt to find other good teachers. But all that back and forth meant I was religiously half-baked. There was catechism in the sense that religious talk happened, but a lot of it consisted of overheard conversations between my dad and the Christian Brothers he worked with, who came over to drink and debate philosophy in our living room. There was the Catholic church we attended, but it was a very Bay Area kind of place with folk Mass and liturgical dance, occasional reflections by female parishioners and late night Mass in the dark. There was an early exodus within our ranks: my mother got sick of the ritual and stopped attending Mass, and soon stopped advocating for the latter end of her five kids to attend Catholic school, which is when I began bouncing around. My father worked for a Catholic school in the suburbs; my mother worked for the public schools in Oakland, where we lived. But even though I was assured by priests and nuns that my baptism made me a Catholic for life, nobody was ever able to explain what being a Catholic really meant. And the one person who might have explained it best to me exited the picture before I knew how to ask the right questions.

In 1989, when I was eighteen, my father crashed his VW van on the way to work. He spent three months the ICU, thrashing and hallucinating with alcoholic DTs and brain trauma, but he seemed to be on the mend by the time I boarded a Greyhound for an overnight ride to Olympia, where I’d be attending an artsy alternative college. I saw him briefly at Christmas and he’d transformed from a bear into a wraith: suddenly, he was white haired and spectrally thin, like something out of a horror film. He died in his sleep one night soon after the New Year.

The funeral was the first Catholic Mass I’d been to in years. As an adolescent I’d occasionally gone to evening Mass on Sundays, with just a guitar for music and near darkness except for a few candles. It the kind of Catholic ceremony I secretly enjoyed, but eventually hormones took over and I blew Dad off when he asked if I’d go along. Instead I sat in my room, listening to the Replacements and scratching out agonized poems to boys who ignored me.

In contrast to the intimate environment of weekly Mass, his funeral was crowded, loud and brightly lit, with oppressive organ music raining down from a balcony crammed with pipes, speeches by his Christian Brother colleagues in their black cassocks and white bibs, and a reception afterwards where I shook hands with people I’d never met before, all of whom wanted to tell some sort of story about my funny, angry, impatient, complicated father.

Dad was an only child born when his parents were nearly forty, and they raised him in an area of West Oakland crammed full of poor Irish. His own father was a dancing-on-tables sort of drunk. One evening, he danced right off of a table and collapsed onto the floor, sending my grandmother into panicked early labor. Dad was tiny and not expected to make it. He did. Everyone had prayed. He was Catholic to the bone, despite his constant swearing, often taking the Lord’s name in vain in surprisingly creative ways (I can still hear him saying “holy bitch tits fucking virgin” over a flat tire), and in spite of his itinerant habit of taking off and leaving us for weeks at a stretch while he pursued a solitude that was lost to him once his five children were born.

After his funeral mass, I didn’t set foot in a church for nearly a decade. But for as much as I subsumed myself in secular (and clearly illegal) activities with too many sulky, disaffected men and boys, somehow I was always being pulled back to prayer. When I was in the back of a car being driven by a very drunk guy and we slammed into a tree, the words out of my mouth were “Oh God please don’t.” I walked away with a sprained hand, and my boyfriend at the time laughed about my holy interjection for months. During a mushroom trip in a boyfriend’s apartment, a corona of flames flickered around his head, and I mumbled “Holy Spirit set you on fire . . . dude” before running off to the bathroom to retch. I developed a habit of crossing myself whenever I saw a cat or dog crushed on the road. All of the guys I’ve dated have been atheists and needless to say, they found my holy inclinations annoying. But for me, there’s something irresistibly sexy about nonbelievers, since it requires such high self-esteem to reject the idea of God altogether. Sartre once said that if God existed, he couldn’t, and if he existed, God couldn’t. If confidence is sex, Sartre must have been the George Clooney of philosophy.

Descriere

As someone who clocked more time in mosh pits and at pro-choice rallies than kneeling in a pew, Kaya Oakes was not necessarily the kind of Catholic girl the Vatican was after. But even while she immersed herself in the punk rock scene and proudly called herself an atheist, something kept pulling her back to the religion of her Irish roots.

After running away from the Church for thirty years, Kaya decides to return. Her marriage is under stress, her job is no longer satisfying, and with multiple deaths in her family, a darkness looms large. In spite of her frustration with Catholic conservatism, nothing brings her peace like Mass. After years of searching to no avail for a better religious fit, she realizes that the only way to find harmony—in her faith and her personal life—is to confront the Church she’d left behind.

Rebellious and hypercritical, Kaya relearns the catechisms and achieves the sacraments, all while trying to reconcile her liberal beliefs with contemporary Church philosophy. Along the way she meets a group of feisty feminist nuns, a “pray-and-bitch” circle, an all-too handsome Italian priest, and a motley crew of misfits doing their best to find their voices in an outdated institution.

This is a story of transformation, not only of Kaya’s from ex-Catholic to amateur theologian, but ultimately of the cultural and ethical pushes for change that are rocking the world’s largest religion to its core.

After running away from the Church for thirty years, Kaya decides to return. Her marriage is under stress, her job is no longer satisfying, and with multiple deaths in her family, a darkness looms large. In spite of her frustration with Catholic conservatism, nothing brings her peace like Mass. After years of searching to no avail for a better religious fit, she realizes that the only way to find harmony—in her faith and her personal life—is to confront the Church she’d left behind.

Rebellious and hypercritical, Kaya relearns the catechisms and achieves the sacraments, all while trying to reconcile her liberal beliefs with contemporary Church philosophy. Along the way she meets a group of feisty feminist nuns, a “pray-and-bitch” circle, an all-too handsome Italian priest, and a motley crew of misfits doing their best to find their voices in an outdated institution.

This is a story of transformation, not only of Kaya’s from ex-Catholic to amateur theologian, but ultimately of the cultural and ethical pushes for change that are rocking the world’s largest religion to its core.