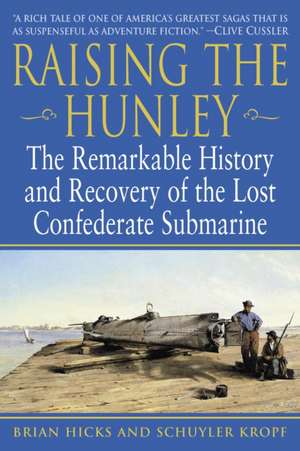

Raising the Hunley: The Remarkable History and Recovery of the Lost Confederate Submarine

Autor Brian Hicks, Schuyler Kropfen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2003

The brainchild of wealthy New Orleans planter and lawyer Horace Lawson Hunley, the Hunley inspired tremendous hopes of breaking the Union’s naval blockade of Charleston, only to drown two crews on disastrous test runs. But on the night of February 17, 1864, the Hunley finally made good on its promise. Under the command of the heroic Lieutenant George E. Dixon, the sub rammed a spar torpedo into the Union sloop Housatonic and sank the ship within minutes, accomplishing a feat of stealth technology that would not be repeated for half a century.

And then, shortly after its stunning success, the Hunley vanished.

This book is an extraordinary true story peopled with a fascinating cast of characters, including Horace Hunley himself, the Union officers and crew who went down with the Housatonic, P. T. Barnum, who offered $100,000 for its recovery, and novelist Clive Cussler, who spearheaded the mission that finally succeeded in finding the Hunley. The drama of salvaging the sub is only the prelude to a page-turning account of how scientists unsealed this archaeological treasure chest and discovered the inner-workings of a submarine more technologically advanced than anyone expected, as well as numerous, priceless artifacts.

Hicks and Kropf have crafted a spellbinding adventure story that spans over a century of American history. Dramatically told, filled with historical details and contemporary color, illustrated with breathtaking original photographs, Raising the Hunley is one of the most fascinating Civil War books to appear in years.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 138.98 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 208

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.60€ • 27.67$ • 21.96£

26.60€ • 27.67$ • 21.96£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 14-28 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345447722

ISBN-10: 0345447727

Pagini: 301

Dimensiuni: 140 x 206 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Editura: Presidio Press

ISBN-10: 0345447727

Pagini: 301

Dimensiuni: 140 x 206 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Editura: Presidio Press

Notă biografică

Brian Hicks is a senior writer with the Post and Courier in Charleston, South Carolina, and the co-author of Into the Wind. The recipient of a number of journalism awards, including the South Carolina Press Association Journalist of the Year, Hicks has covered the Hunley since 1999.

Schuyler Kropf is a senior political reporter with the Post and Courier and the recipient of numerous reporting awards. He has followed the Hunley story since 1995.

Both authors live in Charleston.

From the Hardcover edition.

Schuyler Kropf is a senior political reporter with the Post and Courier and the recipient of numerous reporting awards. He has followed the Hunley story since 1995.

Both authors live in Charleston.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

PIONEERS

She was sleek, cigar-shaped, and black. When she broke the choppy surface of Lake Pontchartrain, water rippled over her pectoral fins, and her flank glistened in the warm sunlight of early Louisiana spring. She was 34 feet long and dove underwater and resurfaced gracefully, slowly, like a porpoise. She was, her builders thought, beautiful.

It was such a shame to sink her.

Pioneer had only just begun to live up to its potential. In trial runs on the lake, the little submarine had performed well, had even blown up an old wreck once in mock combat. There were a few minor annoyances: it had buoyancy problems, was slow to turn, and couldn’t be trusted to keep an even keel. But those things could be improved. Most important, it had accomplished something few boats that came before it had: it could travel underwater and surface at will.

Still, there wasn’t any choice—it had to be scuttled. It was April 25, 1862, and Farragut was closing in on New Orleans. Since Easter weekend the Union fleet had fought its way through Rebel fire-rafts and a barrage of cannon fire from the banks of the lower Mississippi. The Confederate Army had stood its ground for a week, but it couldn’t hold forever. For the South in 1862, Good Friday did not live up to its name.

New Orleans was in a panic. Rear Adm. David Glasgow Farragut was not a man to be trifled with. The feisty, sixty-year-old naval genius credited with the phrases “full steam ahead” and “damn the torpedoes” was nothing short of an American legend. He had been a sailor since he was nine, when he served aboard the USS Essex during the War of 1812. Now Farragut was leading the Union’s fleet in the Gulf of Mexico, and when he moved on New Orleans, it would only be a matter of time before it was his. A day earlier word had reached the city that the admiral’s ships had just finished off Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip 75 miles downriver. Those forts had been the city’s only defense from the open sea, and now they were gone, destroyed. If the largest and most important city in the South couldn’t be guarded against invasion, what chance did the Confederacy stand? People burned belongings they couldn’t carry and couldn’t bear to see fall into Yankee hands. Soon the wrought-iron balconies of the French Quarter would resemble bones, the skeleton of the old city. Very few would stand their ground to fight. New Orleans was a lost cause.

Pioneer could not be allowed to fall into Union hands. It was the South’s newest weapon, and surprise was one of its few advantages. The men knew it must be kept secret. As fires raged across the city, they watched workers open the submarine’s hatch—it had no ballast tanks—and let the murky water seep into its hull. Slowly Pioneer sank into a deep bend in the New Basin Canal between downtown New Orleans and Lake Pontchartrain. It had never even seen combat. Now it would never again resurface under its own power. But before Pioneer disappeared into the muck, the submarine did one very important thing for its builders: it proved they could do it—they could build a working submarine.

They would escape with that knowledge.

The strife that led to the Civil War had been building for decades, but when the fighting actually began, it felt sudden. No one was really ready. Eleven southern states had broken away from the rest of the country in the winter of 1861, as they believed was their right, ill will festering until war broke out a few months later. In many ways this was a conflict of agrarian versus industrial economies and lifestyles. For that reason the farmlands of the South may have been doomed from the start. In the world of the mid–nineteenth century, the South depended on the North to manufacture anything and everything it needed—from buggy parts and all-important farming implements right down to clothing. In some ways it was a one-sided relationship. Nowhere was that more apparent than on the water. The Confederate government had gone to war against the Union with a poor excuse for a navy. There simply wasn’t time to assemble one and no economically feasible way to catch up. Hopelessly outnumbered, the Confederacy had only one hope to break U.S. president Abraham Lincoln’s massive blockade of the entire southern coast: Confederate president Jefferson Davis called on privateer ships to do the work. Privateers were ships owned by regular, although usually wealthy, citizens with permission from the government to attack enemy vessels on its behalf. Their pay was on commission. For the Southern government, it was the only fiscally prudent way to handle things: it didn’t have to ante up until a Yankee ship fell.

It wasn’t a bad idea. Patriotism was perhaps the only thing not in short supply in the South during the War Between the States. There were thousands of men willing to take on the Union Navy in anything that would float and some things that wouldn’t. The Confederate government and rich southern planters further enticed these men by offering ridiculously handsome rewards for every Union ship destroyed. Bringing down the New Ironsides, the North’s seemingly indestructible warship, would net a little privateer $100,000—obscene money for the time. Businessmen were willing to put up a purse because the blockade had clogged the South’s shipping lanes, killing their import/export business. The war was costing them a lot of money. Soon the whole Confederacy would be broke. Something had to give.

The South needed an edge.

This 1860 photograph is the only known image of Horace Lawson Hunley. (Courtesy Louisiana State Museum)

Perhaps it was patriotism that led Horace Lawson Hunley to become a privateer. Or maybe it was the thrill, the notions of glory, that first attracted him. He certainly didn’t need the money. At thirty-seven Hunley had more than most people ever would. He was an attorney, a former state lawmaker, and the deputy chief collector at the customhouse in New Orleans. He owned a plantation outside town and, by the time the war began, had started looking west for land investments. New frontiers were very much on his mind in 1861.

Like the fish-boat that would soon be swimming around in his head, Hunley operated on many different levels. On the surface he was polite, ambitious, and fastidious. He had lifted himself out of a childhood of poverty to the top of the social ladder in antebellum Louisiana. Heavily involved in the political scene, he made bets with friends on nearly every race—from the mayor of New Orleans to the president of the United States. Among his large circle of friends, Hunley’s closest confidant and chief client was his brother-in-law, Robert Ruffin Barrow. Barrow was a sugar baron and one of the richest men in the South: he owned eighteen plantations. Barrow had married Hunley’s younger sister, Volumnia, in 1850 and gained a good friend as well as a wife. Together the two men talked politics and looked for profitable investments. Because Hunley was a bachelor, Volumnia and Barrow were his only family. He kept Volumnia supplied with new books and watched out for Barrow’s expanding business interests. He was a kind and devoted brother to the couple.

Beneath the surface, however, a somewhat different man lurked. Behind piercing dark eyes and a thick black beard, Hunley was driven by a hungry ambition to leave his mark on history. In a tiny ledger he kept in his pocket, Hunley wrote inspirational quotations meant to push him harder: “Procrastination is the thief of time” and “Attend to that which is most important and do not neglect business or duty.” In his daily ledger—a gumbo of legal briefings, political thought, and points to make in letters—Hunley kept his days planned to the hour. He would jot down just about every grandiose scheme that came to mind: “Build in New Orleans an octagonal brick tower, three hundred to six hundred feet high.” In his ledger he kept track of every bet.

Hunley also made notes to himself to read about Great Men. His preoccupation with the lives of historical figures seemed a vain exercise. What makes a Great Man? he wondered. What diseases do they get? He wanted to know everything that might help him succeed in joining their ranks: it seemed he yearned to be recognized as a Great Man. One notation, made less than a year before the war began, said simply, “Get book on the death of Great Men.”

It was not surprising he was drawn to war; he had it in his blood. Hunley was descended from veterans of both the Revolution and the War of 1812. He was born in 1823 in Sumner County, a patch of rolling Tennessee farmland just north of Nashville. Horace was one of four children to come from the marriage of John and Louisa Lawson Hunley, and one of just two to survive childhood. In 1830 only Horace, seven, and his sister Volumnia, two years younger, would make the trip to the Crescent City with their parents. It was an odd move for the family: there was no real reason to go. Most people assumed John Hunley was drawn back to the city of his greatest glory, where he had fought alongside Andrew Jackson in the legendary Battle of New Orleans.

It was exciting for the Hunleys, moving from the rural countryside of Tennessee to a huge, beautiful—and decidedly European—city. But whatever joy they experienced was short-lived. Just a few years after the move, in 1834, John Hunley died following a long, lingering illness, leaving his family stranded in a town where they had no close friends or relatives. But they were too poor to attempt a trip back to Tennessee, so they stayed.

A few hard years later, Louisa remarried, this time to a wealthy planter from New Jersey. That set young Horace on a comfortable course. His stepfather provided Hunley’s entrée into society. As soon as he was old enough, Hunley earned a law degree from the University of Louisiana (now Tulane) and served a session in the legislature as a representative from Orleans Parish. He set up a law practice a short distance from the French Quarter and took on additional work at the customhouse. It was a good, busy life. But until 1860 Hunley had yet to find the destiny for which he so longed. And then talk of war began. It seemed that Hunley, a fierce Southern patriot, had found his calling. That December, just one month before the Union would be dissolved, Hunley began to list in his little notebook the states he thought would secede. The gambling man was right about every state except Delaware.

From the Hardcover edition.

She was sleek, cigar-shaped, and black. When she broke the choppy surface of Lake Pontchartrain, water rippled over her pectoral fins, and her flank glistened in the warm sunlight of early Louisiana spring. She was 34 feet long and dove underwater and resurfaced gracefully, slowly, like a porpoise. She was, her builders thought, beautiful.

It was such a shame to sink her.

Pioneer had only just begun to live up to its potential. In trial runs on the lake, the little submarine had performed well, had even blown up an old wreck once in mock combat. There were a few minor annoyances: it had buoyancy problems, was slow to turn, and couldn’t be trusted to keep an even keel. But those things could be improved. Most important, it had accomplished something few boats that came before it had: it could travel underwater and surface at will.

Still, there wasn’t any choice—it had to be scuttled. It was April 25, 1862, and Farragut was closing in on New Orleans. Since Easter weekend the Union fleet had fought its way through Rebel fire-rafts and a barrage of cannon fire from the banks of the lower Mississippi. The Confederate Army had stood its ground for a week, but it couldn’t hold forever. For the South in 1862, Good Friday did not live up to its name.

New Orleans was in a panic. Rear Adm. David Glasgow Farragut was not a man to be trifled with. The feisty, sixty-year-old naval genius credited with the phrases “full steam ahead” and “damn the torpedoes” was nothing short of an American legend. He had been a sailor since he was nine, when he served aboard the USS Essex during the War of 1812. Now Farragut was leading the Union’s fleet in the Gulf of Mexico, and when he moved on New Orleans, it would only be a matter of time before it was his. A day earlier word had reached the city that the admiral’s ships had just finished off Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip 75 miles downriver. Those forts had been the city’s only defense from the open sea, and now they were gone, destroyed. If the largest and most important city in the South couldn’t be guarded against invasion, what chance did the Confederacy stand? People burned belongings they couldn’t carry and couldn’t bear to see fall into Yankee hands. Soon the wrought-iron balconies of the French Quarter would resemble bones, the skeleton of the old city. Very few would stand their ground to fight. New Orleans was a lost cause.

Pioneer could not be allowed to fall into Union hands. It was the South’s newest weapon, and surprise was one of its few advantages. The men knew it must be kept secret. As fires raged across the city, they watched workers open the submarine’s hatch—it had no ballast tanks—and let the murky water seep into its hull. Slowly Pioneer sank into a deep bend in the New Basin Canal between downtown New Orleans and Lake Pontchartrain. It had never even seen combat. Now it would never again resurface under its own power. But before Pioneer disappeared into the muck, the submarine did one very important thing for its builders: it proved they could do it—they could build a working submarine.

They would escape with that knowledge.

The strife that led to the Civil War had been building for decades, but when the fighting actually began, it felt sudden. No one was really ready. Eleven southern states had broken away from the rest of the country in the winter of 1861, as they believed was their right, ill will festering until war broke out a few months later. In many ways this was a conflict of agrarian versus industrial economies and lifestyles. For that reason the farmlands of the South may have been doomed from the start. In the world of the mid–nineteenth century, the South depended on the North to manufacture anything and everything it needed—from buggy parts and all-important farming implements right down to clothing. In some ways it was a one-sided relationship. Nowhere was that more apparent than on the water. The Confederate government had gone to war against the Union with a poor excuse for a navy. There simply wasn’t time to assemble one and no economically feasible way to catch up. Hopelessly outnumbered, the Confederacy had only one hope to break U.S. president Abraham Lincoln’s massive blockade of the entire southern coast: Confederate president Jefferson Davis called on privateer ships to do the work. Privateers were ships owned by regular, although usually wealthy, citizens with permission from the government to attack enemy vessels on its behalf. Their pay was on commission. For the Southern government, it was the only fiscally prudent way to handle things: it didn’t have to ante up until a Yankee ship fell.

It wasn’t a bad idea. Patriotism was perhaps the only thing not in short supply in the South during the War Between the States. There were thousands of men willing to take on the Union Navy in anything that would float and some things that wouldn’t. The Confederate government and rich southern planters further enticed these men by offering ridiculously handsome rewards for every Union ship destroyed. Bringing down the New Ironsides, the North’s seemingly indestructible warship, would net a little privateer $100,000—obscene money for the time. Businessmen were willing to put up a purse because the blockade had clogged the South’s shipping lanes, killing their import/export business. The war was costing them a lot of money. Soon the whole Confederacy would be broke. Something had to give.

The South needed an edge.

This 1860 photograph is the only known image of Horace Lawson Hunley. (Courtesy Louisiana State Museum)

Perhaps it was patriotism that led Horace Lawson Hunley to become a privateer. Or maybe it was the thrill, the notions of glory, that first attracted him. He certainly didn’t need the money. At thirty-seven Hunley had more than most people ever would. He was an attorney, a former state lawmaker, and the deputy chief collector at the customhouse in New Orleans. He owned a plantation outside town and, by the time the war began, had started looking west for land investments. New frontiers were very much on his mind in 1861.

Like the fish-boat that would soon be swimming around in his head, Hunley operated on many different levels. On the surface he was polite, ambitious, and fastidious. He had lifted himself out of a childhood of poverty to the top of the social ladder in antebellum Louisiana. Heavily involved in the political scene, he made bets with friends on nearly every race—from the mayor of New Orleans to the president of the United States. Among his large circle of friends, Hunley’s closest confidant and chief client was his brother-in-law, Robert Ruffin Barrow. Barrow was a sugar baron and one of the richest men in the South: he owned eighteen plantations. Barrow had married Hunley’s younger sister, Volumnia, in 1850 and gained a good friend as well as a wife. Together the two men talked politics and looked for profitable investments. Because Hunley was a bachelor, Volumnia and Barrow were his only family. He kept Volumnia supplied with new books and watched out for Barrow’s expanding business interests. He was a kind and devoted brother to the couple.

Beneath the surface, however, a somewhat different man lurked. Behind piercing dark eyes and a thick black beard, Hunley was driven by a hungry ambition to leave his mark on history. In a tiny ledger he kept in his pocket, Hunley wrote inspirational quotations meant to push him harder: “Procrastination is the thief of time” and “Attend to that which is most important and do not neglect business or duty.” In his daily ledger—a gumbo of legal briefings, political thought, and points to make in letters—Hunley kept his days planned to the hour. He would jot down just about every grandiose scheme that came to mind: “Build in New Orleans an octagonal brick tower, three hundred to six hundred feet high.” In his ledger he kept track of every bet.

Hunley also made notes to himself to read about Great Men. His preoccupation with the lives of historical figures seemed a vain exercise. What makes a Great Man? he wondered. What diseases do they get? He wanted to know everything that might help him succeed in joining their ranks: it seemed he yearned to be recognized as a Great Man. One notation, made less than a year before the war began, said simply, “Get book on the death of Great Men.”

It was not surprising he was drawn to war; he had it in his blood. Hunley was descended from veterans of both the Revolution and the War of 1812. He was born in 1823 in Sumner County, a patch of rolling Tennessee farmland just north of Nashville. Horace was one of four children to come from the marriage of John and Louisa Lawson Hunley, and one of just two to survive childhood. In 1830 only Horace, seven, and his sister Volumnia, two years younger, would make the trip to the Crescent City with their parents. It was an odd move for the family: there was no real reason to go. Most people assumed John Hunley was drawn back to the city of his greatest glory, where he had fought alongside Andrew Jackson in the legendary Battle of New Orleans.

It was exciting for the Hunleys, moving from the rural countryside of Tennessee to a huge, beautiful—and decidedly European—city. But whatever joy they experienced was short-lived. Just a few years after the move, in 1834, John Hunley died following a long, lingering illness, leaving his family stranded in a town where they had no close friends or relatives. But they were too poor to attempt a trip back to Tennessee, so they stayed.

A few hard years later, Louisa remarried, this time to a wealthy planter from New Jersey. That set young Horace on a comfortable course. His stepfather provided Hunley’s entrée into society. As soon as he was old enough, Hunley earned a law degree from the University of Louisiana (now Tulane) and served a session in the legislature as a representative from Orleans Parish. He set up a law practice a short distance from the French Quarter and took on additional work at the customhouse. It was a good, busy life. But until 1860 Hunley had yet to find the destiny for which he so longed. And then talk of war began. It seemed that Hunley, a fierce Southern patriot, had found his calling. That December, just one month before the Union would be dissolved, Hunley began to list in his little notebook the states he thought would secede. The gambling man was right about every state except Delaware.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Forget the Titanic; this sub wreck is hot.”

–The Wall Street Journal

From the Hardcover edition.

–The Wall Street Journal

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

The history of the Confederate submarine "H.L. Dramatically told, filled with historical details and contemporary color, illustrated with breathtaking original photos, here is a tale as spellbinding as any in American history.