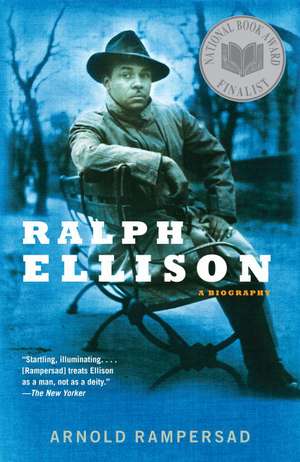

Ralph Ellison: A Biography

Autor Arnold Rampersaden Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2007

Starting with Ellison’s hardscrabble childhood in Oklahoma and his ordeal as a student in Alabama, Rampersad documents his improbable, painstaking rise in New York to a commanding place on the literary scene. With scorching honesty but also fair and compassionate, Rampersad lays bare his subject’s troubled psychology and its impact on his art and on the people about him.This book is both the definitive biography of Ellison and a stellar model of literary biography.

Preț: 140.41 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 211

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.87€ • 29.18$ • 22.57£

26.87€ • 29.18$ • 22.57£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375707988

ISBN-10: 0375707980

Pagini: 657

Ilustrații: 24 PAGES OF B&W PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 35 mm

Greutate: 0.64 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0375707980

Pagini: 657

Ilustrații: 24 PAGES OF B&W PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 35 mm

Greutate: 0.64 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Arnold Rampersad is Senior Associate Dean for the Humanities at Stanford University, where he is also Sara Hart Kimball Professor in the Humanities and a member of the English department. He is a recipient of fellowships from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Rockefeller Foundation. He is also an elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He has written for The New Republic, The Times Literary Supplement, The New York Times Book Review, and The Washington Post.

Extras

Chapter One

In the Territory: 1913–1931

There is no ancestor so powerful as one’s earlier selves.

—Lewis Mumford (1929)

Decades after the blazing hot afternoon in June 1933 when Ralph Ellison, in his first and last outing as a hobo, climbed fearfully and yet eagerly aboard a smoky freight train leaving Oklahoma City on a dangerous journey that he hoped would take him to college in Tuskegee, Alabama, his memories of growing up in Oklahoma continued both to haunt and to inspire him. For a long time he had suppressed those memories; then the time came when he began to crave them.

The turning point had been his triumph in 1952 with his novel Invisible Man. That success had led to a cascading flow of honors such as no other African-American writer had ever enjoyed. In 1953, he won the National Book Award, besting The Old Man and the Sea, by Ernest Hemingway, one of his idols. Later, the American Academy of Arts and Letters elected him a member, one of the fifty distinguished American men and women who formed its inner core. At the White House, first Lyndon B. Johnson and then Ronald Reagan awarded him presidential medals. At the behest of the novelist and critic André Malraux, another of his idols, France made him a Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters. The most venerable social club in America connected to the arts, the Century, in New York, elected him as its first black member. Harvard University, awarding him an honorary degree, offered him a professorship. Never out of print and translated into more than twenty languages, Invisible Man maintains its reputation as one of the jewels of twentieth-century American fiction.

Ellison’s triumph in 1952 had also led to a tangled mess of fears and doubts about his ability to finish a second novel at least as fine as Invisible Man. By the time of his death in 1994, his failure to produce that second novel had made Ellison, a proud man, the butt of surreptitious jokes and cruel remarks. The snickering and giggling behind his back often left him prickly and tart, if not downright hostile. Clinging fearlessly and stubbornly to the ideal of harmonious racial integration in America, he found it hard to negotiate the treacherous currents of American life in the volatile 1960s and 1970s. Although he always saw himself as above all an artist, and published a dazzling book of cultural commentary in 1964, his later successes were relatively modest. For some of his critics, his life was finally a cautionary tale to be told against the dangers of elitism and alienation, and especially alienation from other blacks. For his admirers, however, no one who had written Invisible Man and so skillfully explicated the matter of race and American culture in his essays could ever be accounted a failure. To some people—younger black writers mainly—who hoped and perhaps even expected him to help them, he frequently seemed cold and stingy. To others—whites especially—he was a man of grace, intelligence, wit, and courage who saw his nation with prophetic optimism and clarity.

Each of these conflicting views had, at the very least, an element of truth—and the roots of these conflicts may be traced, not surprisingly, to his upbringing in Oklahoma. Seeking artistic inspiration as the decades passed, he turned more and more to memories of his youth in what once had been the old Indian and Oklahoma territories. From this virgin land—as both whites and blacks saw it—the state of Oklahoma had been carved in 1907. Certainly he had no interest in living as a mature man in Oklahoma. It was more than enough for him to brood on the past, and to come back every seven years or so to visit the old neighborhoods, talk with old friends, bask in the glow of his celebrity, and revive his creativity at its ancestral source. On these visits, he looked sorrowfully on the banal evidence of “progress” and “urban renewal” that marred the city, and even more sadly on the spectral presence of those old friends now dead and gone. “When I get there I’m like a ghost,” he declared once, “or a Rip Van Winkle who has slept for twenty years and awoke to discover that his world has changed—but how! . . . An obsessive refrain sounds in my mind: Where have they all gone? Where, oh where?”

Fascinated by the power of myth and legend, and alert to the ways in which geography often means fate, he saw Oklahoma as embodying some of the more mysterious forces in American culture. He believed that the region possessed or had possessed almost every element concerning power, race, and art that is essential to understanding the nation. It had Indians, whites, and blacks; treaties solemnly made and shamelessly broken; despair and hope, failure and shining success. Here was the legacy of the dispossession of the Five Civilized Tribes—Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole—from their homelands in the South and their expulsion in the 1820s and 1830s, by way of the Trail of Tears, to Indian Territory. (Ralph cherished the fact that he was “a wee bit Creek!” on his mother’s side, just as he was also proud of the white ancestry on both sides of his family and the black ancestry that was predominant in his physical features.) In 1879, whites had entered Indian Territory for the first time, with the avowed aim of seizing much of the land. Divided and united by history, Oklahoma was culturally the Wild West, the Southwest, and the Old South; it was ancient but also brazenly new. One day, Oklahoma City did not exist. The next day, April 22, 1889, after settlers had raced to stake their claims as part of the official Great Land Run, its population stood at ten thousand. The Oklahoma Territory was born. Ironically, helping to keep in line any indignant Indians were the famous “Buffalo Soldiers” of the 10th Cavalry.

Ralph, born only six years after Oklahoma became a state, could put human faces—black, white, Indian, and mixed—on this past. For the freed slaves and their children and for free blacks in general, Indian Territory had meant at first an almost providential deliverance from Jim Crow. Many blacks rushed to claim the one-hundred-acre parcels of land allotted by the government to new settlers, so that by 1900 almost sixty thousand blacks lived in the Indian and Oklahoma territories. Many of them saw Oklahoma the way Mormons had seen the new territory that became Utah. Twenty-eight all-black towns sprang up. Edward P. McCabe, a passionate spokesman for black migration and the establishment of a black state, implored his fellow African-Americans to make history: “What will you be if you stay in the South? Slaves liable to be killed at any time, and never treated right; but if you come to Oklahoma you have equal chances with the white man, free and independent.”

This was the promise that in 1910 lured a young, newly wed couple, Lewis and Ida Ellison, to Oklahoma City. Their first child, Alfred, died as an infant. Their second, Ralph Waldo Ellison, was born at 407 East First Street, in Oklahoma City, on March 1, 1913. For most of his life Ralph would offer 1914 as the correct year. Presented with a chance to do so, around 1940—and despite the fact that he was on the whole fastidiously honest—Ralph decided to shave a year from the record. The U.S. Census taker got it right in January 1920 when he listed Ralph Ellison as being six years old, born in 1913. A note in his mother’s hand, written behind a photograph of Ralph as a toddler, sets his time and date of birth as 11 a.m. on Saturday, March 1, 1914. But March 1 fell on a Friday in 1913, not in 1914. Someone had changed 1913 to 1914 after an erasure. Moreover, Ralph always insisted he was three years old when the worst disaster of his life occurred: On July 19, 1916, his father died after an operation in the University Emergency Hospital in Oklahoma City.

Ralph was a healthy baby. A photograph of him at four months in a washtub shows him, as he later put it, as a “fat little blob of blubber.” According to family lore, at six months he took his first steps. At thirteen months, he startled his father by seeming to crave steak and onions. At two, he began to talk. Blessed with a sharp memory, he recalled a doting father. “I rem[em]ber toys, toys, and still more toys,” he wrote. He recalled his father allowing him one evening to splash in the bathtub while his mother went off with a friend to a concert. He also recalled his father reading incessantly but making time, too, for his young son (“my father had two passions, children and books”). Either his father or mother was responsible for “the first song taught me as a two-year-old” (“Dark Brown, Chocolate to the Bone”), as well as for his command of a wildly popular, risqué dance to go with it, the Eagle Rock. His father took him on his horse-drawn wagon through various neighborhoods as he delivered ice and coal to businesses and homes. Ralph never forgot his father’s tenderness. “Mr. Bub,” as some customers called Lewis Ellison, explained things “patiently, lovingly,” as they ventured into “ice plants, ice cream plants, packing plants, shoe repair and blacksmith shops, bottling works and bakeries.” Ralph also never forgot the day in Salter’s grocery store when he watched his father climb some steps and attempt to hoist a hundred-pound block of ice into a cabinet. When a shard of ice pierced his stomach, Lewis Ellison staggered and collapsed.

Ralph remembered the lingering illness, the internal wound that would not heal, the decision to operate, and their last visit together in the hospital. As he prepared to leave with his mother, his father slipped a blue cornflower into Ralph’s lapel and gave him pink and yellow wildflowers from a vase on a windowsill. Then his father was wheeled away and Ralph saw his father alive for the last time. “I could see his long legs,” Ralph would write (the emphasis his own), “his knees propped up and his toes flexing as he rested there with his arms folded over his chest, looking at me quite calmly, like a kindly king in his bath. I had only a glimpse, then we were past.” The official death certificate identified the cause of death as “Ulcer of stomach followed by puncture of same.” He was thirty-nine years old.

Ralph’s life was changed forever. So, too, were the lives of his mother and his brother, Herbert Maurice Ellison, who was then only a few weeks old. The emotional cost was incalculable, and in all matters involving money the change was a disaster. Ahead lay years of shabby rented rooms, hand-me-down clothing, second-rate meals, sneers and slights from people better off, and a pinched, scuffling way of life. For the Ellisons, Oklahoma City took on a radically new character. Almost every aspect of Ralph’s life became tougher, sadder. He would take many years to recover fully from the shock of his father’s death, if he ever did. He inherited no money but rather a powerful physique; a nimble mind; a worn copy of a book of verse, which would perhaps compel Ralph to write his own book; and the name Ralph Waldo Ellison, in honor of Ralph Waldo Emerson, the famous American poet and essayist of the nineteenth century. He also inherited what his mother had “often warned us against,” Ralph noted, “giving in to what she considered the Ellisons’ sin of inordinate pride.”

Ellison pride, which would both empower and hobble Ralph, could be traced back to the patriarch of the family, Alfred Ellison, and his wife, Harriet Walker Ellison, of the small town of Abbeville Court House, South Carolina. Harriet was long dead by 1916, but Alfred was still vigorous at seventy-one. He was the father of ten children, including Lewis and Lucretia Ellison Brown. Lucretia migrated to Oklahoma City in 1910 with Lewis and Ida, bringing with her Tom, Francis, and May Belle Brown, her three children by her divorced husband. The death of Lewis, Alfred’s eldest son, hit him hard. At his request later that year, Tom and May Belle took their three-year-old cousin by train on an extended visit to Abbeville. Ralph found the visit both disturbing and a welcome diversion. Many decades later, he would recall “quite vividly” the train approaching Abbeville across a muddy river and Uncle Jim, one of his father’s brothers, waiting in a horse-drawn carriage. He fondly remembered Alfred, who was a huge, muscular man, and other members of the Ellison clan.

The Ellisons lived in a large old house with fireplaces “into which I could walk around and see the light filtering down the chimneys.” Ralph recalled an abundance of melons and vegetables heaped on the back porch. He walked in a grove of pecan trees that his father had planted as a boy (for many years afterward, at Christmas, a bag of pecan nuts from this grove reached the Ellisons in Oklahoma City). He slept in an enormous feather bed and was fascinated by a ruined church, its stained-glass windows intact, next door; now it served as a chicken house. He loved the profusion of luna moths and fireflies that glowed in the balmy South Carolina dark. “By way of entertaining a small sorrowful visitor from the west,” a kindly local boy, Eddie Hugh Wilson, filled a glass jar with lightning bugs and presented them to the weepy child “as a glowing toy.”

Ralph left Abbeville just before one of the more heinous crimes in its history. On October 21, a mob of whites dragged Anthony Crawford, one of the most prosperous black farmers in the region, from a local jail after the sheriff had arrested him for insulting a white man. The mob then lynched him. Ralph would not visit Abbeville again. Less than two years later, on May 23, 1918, Alfred died. Proud to be an Ellison, Ralph would learn about his paternal grandfather later in life. Alfred had been born a slave in South Carolina in 1845, had remained illiterate, but had also shown uncommon intelligence, integrity, and grit during the perilous Reconstruction. After the war he married Harriet, who was virtually white, and settled down with her in Abbeville. At first, they both worked in some form of domestic service. He also entered Republican Party politics during the brief postwar period when black voters outnumbered their white counterparts in the community. He was an important member of the black Union League, which aimed to preserve the advances made after Emancipation. He tried all his life to keep up with the flux of current events, and to recognize the maneuverings of power about him. His reward was first a post as constable, then as town marshal in Abbeville. Charged with preserving order among blacks and whites, he gained a reputation for being fair to all.

When Reconstruction ended with the Hayes-Tilden Compromise and the withdrawal of federal troops from the South in April 1877, Alfred’s position became tenuous. Whites stepped up their efforts to recapture power and influence in the region. In elections held the previous year, violence had disrupted sleepy Abbeville. The white Abbeville Medium made it clear that “the Democratic party means to carry this state in the next election . . . by fair or foul means.” Many blacks sank into a kind of neo-slavery, or headed north or west. Alfred Ellison was different. When whites killed one of his closest friends, he was defiant. On one occasion, he strode down the main street in Abbeville, trailed by unfriendly whites. “If you’re going to kill me,” he challenged them, “you’ll have to kill me right here because I’m not leaving. This is where I have my family, my farm and my friends; and I don’t plan to leave.” Soon, whites stripped him and other blacks of power. In 1877, Lewis was born, after three daughters. Six other children came later. The family was never destitute; Alfred’s prestige remained high in the black community, and not without substance in the white. Owning a valuable lot of land in town, he also maintained a horse-drawn dray that earned him money, especially during the cotton season. At times, he and his brothers built trestles for the Southern Railroad. In 1884, he made the local news briefly. “Big Alfred” Ellison, as a white newspaper reporter called him, got into a fistfight with “Beef Sam [Marshall], both tremendous specimens of physical manhood,” when tempers flared as they were moving a piano to the train depot. Ellison was thrashing Beef Sam when Sam stuck a knife three inches into his stomach. Ellison recovered. After his wife and one of their children perished in a house fire, the family’s standing was such that the white newspaper carried a notice of Harriet’s death without reference to her race.

Unlike Alfred, young Lewis Ellison learned to read and write, although the extent of his formal education is unknown. Like his father, he was brave. On May 31, 1898, at the age of twenty-one, he responded to President William McKinley’s national call to arms against Spain in Cuba and the Philippines by traveling to Atlanta, where he joined the U.S. Army as a volunteer. After basic training in Georgia, he was assigned to Company F of the 25th United States Colored Infantry. Although family lore placed Lewis with Company F and Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders at the battle of San Juan Heights, it’s clear that he was not in Cuba at the time. He was sent to the Philippines, the other major theater of the Spanish-American War, in 1899. Showing courage under fire, he rose to the rank of lance corporal. Family lore also had him serving in the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion in China, but no evidence exists of that service either. However, two recorded episodes indicate that Lewis had become disillusioned with the Jim Crow army. First, he was demoted to the rank of private. Then, on April 9, 1901, he was court-martialed. He had refused to obey orders to drill in hot, humid weather as punishment for allegedly gambling (he was apparently sick with malaria). The court sentenced him to two years at hard labor. Released later that year, he was dishonorably discharged.

What might have spelled social disaster for a young white man was not as heavy a burden for a black man, whose opportunities were already constricted by Jim Crow. Returning to Abbeville around 1901, Lewis started an ice-cream parlor and candy store. The venture fizzled. Nevertheless, he had enough money in 1902 to finance a mortgage of $125 on his father’s house and land. At some point, he took a job with a construction company in Chattanooga, Tennessee, that specialized in high-rise steel-and-concrete buildings. Soon, he found an enticing reason to stay at home in Abbeville. Among his friends was a handsome young couple—Maston Watkins, a fireman employed by the Southern Railroad, and his attractive wife, Ida Milsap “Brownie” Watkins, from the farming town of White Oak in southeastern Georgia, who had attended Ferguson-Williams Academy in Abbeville. One day, when Watkins was at his job on a train, a group of idle young whites placed a skiff on the tracks to see what would happen. The train derailed, and Watkins was killed. Lewis consoled Brownie, which turned into love and, eventually, marriage. Within a month of their marriage, the couple left Abbeville for a new life in the West.

In April 1910, they were living in Oklahoma City. Starting out as a common street laborer, Lewis soon returned to construction work. For a while, as a foreman, he hired and fired workers. Later, his son Ralph took pride in knowing that his father had helped to build some of the most impressive buildings in the city. Sprawling over the largest municipality in the United States, Oklahoma City should have provided ample opportunity for an experienced construction worker, but Jim Crow ruled even before the state was born in 1907, and Lewis could go only so far in any white-owned business there. In 1907, the populist Democratic politician William H. “Alfalfa Bill” Murray, then president of the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention (and much later a governor of the state), told whites that while “we must provide the means for the advancement of the negro race, and accept him as God gave him to us and use him for the good of society,” the black man “must be taught in the line of his own sphere, as porters, boot-blacks and barbers, and many lines of agriculture. . . . It is an entirely false notion that the negro can rise to the level of a white man in the professions or become an equal citizen to grapple with public questions.” Unless they worked for themselves, blacks got only menial jobs. By now most realized that emigration to Oklahoma probably had been a mistake, yet another black dream frustrated by whites. So Lewis believed. Late in April 1912, when he wrote to Ida from Texas, he mourned the fact that Oklahoma had brought him “much worry and much grief. I am sorry there ever was such a place.” He hoped that his luck would change soon: “I don’t want and don’t intend to be there another winter.”

As it turned out, he endured four more Oklahoma winters. Often he was away, working and saving money. At such times he was solicitous of his wife. “Your baby is sorry he cannot come to his baby when she wants him,” he wrote once to her. “I know how you feel about that and I will pay you well when I get there.” Back in Oklahoma City he started his ice and coal business and planned to buy a house (though he now owned his father’s old house in Abbeville). He and Ida were living in a rooming house when Dr. Wyatt H. Slaughter, the leading black physician in Oklahoma City, delivered Ralph. Needing more space, they rented a house not far away, and then another, on North Byers, surrounded by whites, as Lewis tried to make his family comfortable and give his son a secure start in the world.

When he died in 1916, Lewis left behind the well-thumbed “thick anthology of poetry” that became one of Ralph’s dearest possessions. What did his father know of Emerson, really? Lewis’s letters to Ida—the few that have survived—suggest a poor education, though it’s possible that he had started life with certain interests and tastes only to have them, and his entire sensibility, coarsened by racism. This was, after all, the main purpose of Jim Crow laws and conventions, to reduce blacks to neo-slavery. It’s also possible that his choice of Ralph’s resounding full name was sparked by the fact that his boy was born in a house owned by a man named Jefferson Davis Randolph, who had named his eldest son Thomas Jefferson Randolph. Only late in life did Ralph assert that Emerson had meant much not only to his father but also to other blacks in Oklahoma. “I can’t forget Emerson’s powerful force in the life of my father,” Ralph wrote then, “or the spiritual and intellectual support he provided several of my teachers and community leaders.” According to Ralph, “Emerson’s voice rang loud in Negro communities and influenced my own elders’ decision to seek a broader freedom out in the Territory. . . . Emerson got to me in the classroom no less than at home; in drug store, barbershop, and dental chair, as well as on the playing field. He was also a spur to some of my father’s white friends, and thus sponsored a community of hope.”

The pretentious name would embarrass Ralph for much of his early life, when he sometimes used to claim that Ralph Waldo Ellison was a boy who lived next door. Then, as a teenager, he reconciled himself to, and even embraced, his full name. He didn’t embrace the “hidden name and complex fate” because he came to believe in Emerson’s transcendentalism. Instead, claiming the full American heritage, he began to treasure his nominal connection to the so-called American Renaissance, when Ralph Waldo Emerson, Herman Melville, Walt Whitman, and Henry David Thoreau, among others, penned some of the most influential works of American literature. Ralph would see this movement as a golden moment almost unparalleled in the evolution of the nation. In the Age of Emerson, abolitionist moral fervor had made the black man—the slave—the one true symbol of the American conscience. He also then came to appreciate, however faintly traced, his father’s ambition for him. “After I began to write and work with words,” he recalled, “I came to suspect that he was aware of the suggestive powers of names and of the magic involved in naming.”

Thus the link between father and son continued long after Lewis’s death. Ironically, the son probably wouldn’t have become famous if his father had lived. Protected, perhaps even cosseted, by his father’s love, he would probably have escaped the wounds of poverty, loneliness, and despair that came howling in the wake of Lewis’s death. Later, he resented suggestions that his father’s death had marred him. “What quality of love sustains us in our orphan’s loneliness,” he asked, in words he himself stressed, “and how much is thus required of fatherly love to give us strength for all our life thereafter?” He protested—perhaps too much—against the idea that his father’s death might have crippled him: “What statistics, what lines on whose graphs can ever convince me that by his death I was fatally flawed and doomed—afraid of women, derelict of duty, sad in the sack, cold in the crotch, a rolling stone in social space, a spiritual delinquent, a hater of self—me in whose face his image shows?” As Ralph told it, his mother’s reverence of his father’s memory had made all the difference: “His strength became my mother’s strength and my brother and I the confused, sometimes bitter, but most often proud, recipients of their values and their love.”

Nevertheless, as a youth he would be “bemused by a recurring fantasy in which, on my way to school of a late winter day I would emerge from a cold side street into the warm spring sun and there see my father, dead since I was three, rushing toward me with a smile of recognition and outstretched arms. And I would run proudly to greet him, his son grown tall.” Astutely, Ralph would later define the blues, which may be at the core of modern African-American artistry, as “an impulse to keep the painful details and episodes of a brutal experience alive in one’s aching consciousness, to finger its jagged grain, and to transcend it, not by the consolation of philosophy but by squeezing from it a near-tragic, near-comic lyricism.” For him, the most dangerously “jagged grain,” fingered in his youth and still wounding in his adult years, would be his father’s untimely death. Only eventually would Ralph learn to make art out of this loss, and hope thus to transcend it.

The new life of poverty started almost at once. Finding money to bury Lewis was hard. His body had begun to rot and stink in the summer heat, as Ida told Ralph later, before she was able to bury him in Fairlawn Cemetery. Fortunately, she found a job quickly, as a nursemaid for a Jewish family. Lewis had counted several whites, including several members of the small Jewish community, among his friends. Now working in service for the first time, even as she cared for her own infant, Herbert, Ida would spend the rest of her life mainly as a hotel maid or a janitor. At first, people rushed to help her. Co-worshippers at Avery Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church moved her into its vacant parsonage. She made friends easily. However, as Ralph grew toward adolescence and young manhood, he watched his mother slip down the social ladder until, in the end, she had lost whatever cachet she had brought with her to Oklahoma as a pretty young bride.

No one was more important to her and her little boys than the Randolphs, in whose rooming house Ralph had been born. Heading the family were Jefferson Davis (J.D.) Randolph and his wife, Uretta. Their eldest child, Edna Randolph Slaughter, was for some years Ida’s closest friend; Edna was the wife of Dr. Wyatt Slaughter, the wealthy, property-acquiring physician who had delivered Ralph. After supper in the evenings, Ida, Ralph, and Herbert sometimes went window-shopping with Edna and her princely children, Wyatt Jr. and Saretta. Edna’s two younger sisters, Camille and Iphigenia (“Cute”), were like older sisters to the Ellison boys. Edna’s brothers—the dentist Dr. Thomas Jefferson “Bud” Randolph and the pharmacist Dr. James L. “Jim” Randolph—also took a lively interest in young Ralph. Separately, Tom and Jim would employ him even before he was a teenager.

The Randolphs and the Slaughters were a prominent part of the black leadership of Oklahoma City, which included men and women in business, religion, medicine, dentistry, education, and law. These people both tested segregation and sometimes grew rich from it. For many years, Jim Crow had caged the city’s blacks into scattered pockets. After World War I, however, one area emerged to consolidate the power of the community. This neighborhood was near the thriving downtown district, as the city boomed as a result of the state’s agriculture and abundance of oil wells. Its disadvantages included being close to the railroad tracks that served the bustling stockyards (soon to become the largest cattle market in the world). It was also close to the city’s major red-light district, where prostitutes of all colors plied their trade in segregated whorehouses.

By the early 1920s, in Ralph’s boyhood, the heart of black life in Oklahoma City would be the vibrant block on Second Street between Central and Stiles that came to be known locally as “Deep Second” or “Deep Deuce.” This block housed the community’s drugstores, doctors’ offices, funeral homes, hotels, haberdasheries, restaurants, pool halls, and repair shops, as well as its crusading newspaper, the Black Dispatch. Here also were the Aldridge Theater (hailed as the finest theater for blacks south of Chicago) and Slaughter’s Dance Hall (taking up the third floor of Dr. Slaughter’s biggest building). Between visiting celebrities such as Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong, or hot local talent such as the Blue Devils Orchestra, Deep Second made Oklahoma City second only to Kansas City among jazz centers west of Chicago. The major churches, too, were there or nearby. On East California stood the main school for blacks, the combined Douglass (Colored School) Elementary School and High School, as officials called it. In 1919, Ralph would enter the first grade at Douglass; aside from brief stints elsewhere, he would study there until finishing in 1932 as a member of the class of 1931.

Before Ralph became thoroughly familiar with Deep Second, including its taverns and dancehalls, he led a sheltered life as Ida, his Aunt Lucretia and her children, and the Randolph and Slaughter clans tried to fill the terrible void caused by his father’s death. Although Aunt Lucretia was a formal woman, she dearly loved her brother’s two boys; her children also showered gifts and favors on their young cousins. Lucretia’s irreverent son, Tom, was much older than Ralph but never played the serious adult with him. Instead, he treated him more like a pal. For fifty years a brakeman on the Frisco Railroad, Tom loved whiskey, cigars, fishing, tinkering with cars, and traveling. “He was also a ladies man,” Ralph noted, “whose attraction for good looking young women must surely have influenced my own taste by the time I reached adolescence.”

From the Hardcover edition.

In the Territory: 1913–1931

There is no ancestor so powerful as one’s earlier selves.

—Lewis Mumford (1929)

Decades after the blazing hot afternoon in June 1933 when Ralph Ellison, in his first and last outing as a hobo, climbed fearfully and yet eagerly aboard a smoky freight train leaving Oklahoma City on a dangerous journey that he hoped would take him to college in Tuskegee, Alabama, his memories of growing up in Oklahoma continued both to haunt and to inspire him. For a long time he had suppressed those memories; then the time came when he began to crave them.

The turning point had been his triumph in 1952 with his novel Invisible Man. That success had led to a cascading flow of honors such as no other African-American writer had ever enjoyed. In 1953, he won the National Book Award, besting The Old Man and the Sea, by Ernest Hemingway, one of his idols. Later, the American Academy of Arts and Letters elected him a member, one of the fifty distinguished American men and women who formed its inner core. At the White House, first Lyndon B. Johnson and then Ronald Reagan awarded him presidential medals. At the behest of the novelist and critic André Malraux, another of his idols, France made him a Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters. The most venerable social club in America connected to the arts, the Century, in New York, elected him as its first black member. Harvard University, awarding him an honorary degree, offered him a professorship. Never out of print and translated into more than twenty languages, Invisible Man maintains its reputation as one of the jewels of twentieth-century American fiction.

Ellison’s triumph in 1952 had also led to a tangled mess of fears and doubts about his ability to finish a second novel at least as fine as Invisible Man. By the time of his death in 1994, his failure to produce that second novel had made Ellison, a proud man, the butt of surreptitious jokes and cruel remarks. The snickering and giggling behind his back often left him prickly and tart, if not downright hostile. Clinging fearlessly and stubbornly to the ideal of harmonious racial integration in America, he found it hard to negotiate the treacherous currents of American life in the volatile 1960s and 1970s. Although he always saw himself as above all an artist, and published a dazzling book of cultural commentary in 1964, his later successes were relatively modest. For some of his critics, his life was finally a cautionary tale to be told against the dangers of elitism and alienation, and especially alienation from other blacks. For his admirers, however, no one who had written Invisible Man and so skillfully explicated the matter of race and American culture in his essays could ever be accounted a failure. To some people—younger black writers mainly—who hoped and perhaps even expected him to help them, he frequently seemed cold and stingy. To others—whites especially—he was a man of grace, intelligence, wit, and courage who saw his nation with prophetic optimism and clarity.

Each of these conflicting views had, at the very least, an element of truth—and the roots of these conflicts may be traced, not surprisingly, to his upbringing in Oklahoma. Seeking artistic inspiration as the decades passed, he turned more and more to memories of his youth in what once had been the old Indian and Oklahoma territories. From this virgin land—as both whites and blacks saw it—the state of Oklahoma had been carved in 1907. Certainly he had no interest in living as a mature man in Oklahoma. It was more than enough for him to brood on the past, and to come back every seven years or so to visit the old neighborhoods, talk with old friends, bask in the glow of his celebrity, and revive his creativity at its ancestral source. On these visits, he looked sorrowfully on the banal evidence of “progress” and “urban renewal” that marred the city, and even more sadly on the spectral presence of those old friends now dead and gone. “When I get there I’m like a ghost,” he declared once, “or a Rip Van Winkle who has slept for twenty years and awoke to discover that his world has changed—but how! . . . An obsessive refrain sounds in my mind: Where have they all gone? Where, oh where?”

Fascinated by the power of myth and legend, and alert to the ways in which geography often means fate, he saw Oklahoma as embodying some of the more mysterious forces in American culture. He believed that the region possessed or had possessed almost every element concerning power, race, and art that is essential to understanding the nation. It had Indians, whites, and blacks; treaties solemnly made and shamelessly broken; despair and hope, failure and shining success. Here was the legacy of the dispossession of the Five Civilized Tribes—Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole—from their homelands in the South and their expulsion in the 1820s and 1830s, by way of the Trail of Tears, to Indian Territory. (Ralph cherished the fact that he was “a wee bit Creek!” on his mother’s side, just as he was also proud of the white ancestry on both sides of his family and the black ancestry that was predominant in his physical features.) In 1879, whites had entered Indian Territory for the first time, with the avowed aim of seizing much of the land. Divided and united by history, Oklahoma was culturally the Wild West, the Southwest, and the Old South; it was ancient but also brazenly new. One day, Oklahoma City did not exist. The next day, April 22, 1889, after settlers had raced to stake their claims as part of the official Great Land Run, its population stood at ten thousand. The Oklahoma Territory was born. Ironically, helping to keep in line any indignant Indians were the famous “Buffalo Soldiers” of the 10th Cavalry.

Ralph, born only six years after Oklahoma became a state, could put human faces—black, white, Indian, and mixed—on this past. For the freed slaves and their children and for free blacks in general, Indian Territory had meant at first an almost providential deliverance from Jim Crow. Many blacks rushed to claim the one-hundred-acre parcels of land allotted by the government to new settlers, so that by 1900 almost sixty thousand blacks lived in the Indian and Oklahoma territories. Many of them saw Oklahoma the way Mormons had seen the new territory that became Utah. Twenty-eight all-black towns sprang up. Edward P. McCabe, a passionate spokesman for black migration and the establishment of a black state, implored his fellow African-Americans to make history: “What will you be if you stay in the South? Slaves liable to be killed at any time, and never treated right; but if you come to Oklahoma you have equal chances with the white man, free and independent.”

This was the promise that in 1910 lured a young, newly wed couple, Lewis and Ida Ellison, to Oklahoma City. Their first child, Alfred, died as an infant. Their second, Ralph Waldo Ellison, was born at 407 East First Street, in Oklahoma City, on March 1, 1913. For most of his life Ralph would offer 1914 as the correct year. Presented with a chance to do so, around 1940—and despite the fact that he was on the whole fastidiously honest—Ralph decided to shave a year from the record. The U.S. Census taker got it right in January 1920 when he listed Ralph Ellison as being six years old, born in 1913. A note in his mother’s hand, written behind a photograph of Ralph as a toddler, sets his time and date of birth as 11 a.m. on Saturday, March 1, 1914. But March 1 fell on a Friday in 1913, not in 1914. Someone had changed 1913 to 1914 after an erasure. Moreover, Ralph always insisted he was three years old when the worst disaster of his life occurred: On July 19, 1916, his father died after an operation in the University Emergency Hospital in Oklahoma City.

Ralph was a healthy baby. A photograph of him at four months in a washtub shows him, as he later put it, as a “fat little blob of blubber.” According to family lore, at six months he took his first steps. At thirteen months, he startled his father by seeming to crave steak and onions. At two, he began to talk. Blessed with a sharp memory, he recalled a doting father. “I rem[em]ber toys, toys, and still more toys,” he wrote. He recalled his father allowing him one evening to splash in the bathtub while his mother went off with a friend to a concert. He also recalled his father reading incessantly but making time, too, for his young son (“my father had two passions, children and books”). Either his father or mother was responsible for “the first song taught me as a two-year-old” (“Dark Brown, Chocolate to the Bone”), as well as for his command of a wildly popular, risqué dance to go with it, the Eagle Rock. His father took him on his horse-drawn wagon through various neighborhoods as he delivered ice and coal to businesses and homes. Ralph never forgot his father’s tenderness. “Mr. Bub,” as some customers called Lewis Ellison, explained things “patiently, lovingly,” as they ventured into “ice plants, ice cream plants, packing plants, shoe repair and blacksmith shops, bottling works and bakeries.” Ralph also never forgot the day in Salter’s grocery store when he watched his father climb some steps and attempt to hoist a hundred-pound block of ice into a cabinet. When a shard of ice pierced his stomach, Lewis Ellison staggered and collapsed.

Ralph remembered the lingering illness, the internal wound that would not heal, the decision to operate, and their last visit together in the hospital. As he prepared to leave with his mother, his father slipped a blue cornflower into Ralph’s lapel and gave him pink and yellow wildflowers from a vase on a windowsill. Then his father was wheeled away and Ralph saw his father alive for the last time. “I could see his long legs,” Ralph would write (the emphasis his own), “his knees propped up and his toes flexing as he rested there with his arms folded over his chest, looking at me quite calmly, like a kindly king in his bath. I had only a glimpse, then we were past.” The official death certificate identified the cause of death as “Ulcer of stomach followed by puncture of same.” He was thirty-nine years old.

Ralph’s life was changed forever. So, too, were the lives of his mother and his brother, Herbert Maurice Ellison, who was then only a few weeks old. The emotional cost was incalculable, and in all matters involving money the change was a disaster. Ahead lay years of shabby rented rooms, hand-me-down clothing, second-rate meals, sneers and slights from people better off, and a pinched, scuffling way of life. For the Ellisons, Oklahoma City took on a radically new character. Almost every aspect of Ralph’s life became tougher, sadder. He would take many years to recover fully from the shock of his father’s death, if he ever did. He inherited no money but rather a powerful physique; a nimble mind; a worn copy of a book of verse, which would perhaps compel Ralph to write his own book; and the name Ralph Waldo Ellison, in honor of Ralph Waldo Emerson, the famous American poet and essayist of the nineteenth century. He also inherited what his mother had “often warned us against,” Ralph noted, “giving in to what she considered the Ellisons’ sin of inordinate pride.”

Ellison pride, which would both empower and hobble Ralph, could be traced back to the patriarch of the family, Alfred Ellison, and his wife, Harriet Walker Ellison, of the small town of Abbeville Court House, South Carolina. Harriet was long dead by 1916, but Alfred was still vigorous at seventy-one. He was the father of ten children, including Lewis and Lucretia Ellison Brown. Lucretia migrated to Oklahoma City in 1910 with Lewis and Ida, bringing with her Tom, Francis, and May Belle Brown, her three children by her divorced husband. The death of Lewis, Alfred’s eldest son, hit him hard. At his request later that year, Tom and May Belle took their three-year-old cousin by train on an extended visit to Abbeville. Ralph found the visit both disturbing and a welcome diversion. Many decades later, he would recall “quite vividly” the train approaching Abbeville across a muddy river and Uncle Jim, one of his father’s brothers, waiting in a horse-drawn carriage. He fondly remembered Alfred, who was a huge, muscular man, and other members of the Ellison clan.

The Ellisons lived in a large old house with fireplaces “into which I could walk around and see the light filtering down the chimneys.” Ralph recalled an abundance of melons and vegetables heaped on the back porch. He walked in a grove of pecan trees that his father had planted as a boy (for many years afterward, at Christmas, a bag of pecan nuts from this grove reached the Ellisons in Oklahoma City). He slept in an enormous feather bed and was fascinated by a ruined church, its stained-glass windows intact, next door; now it served as a chicken house. He loved the profusion of luna moths and fireflies that glowed in the balmy South Carolina dark. “By way of entertaining a small sorrowful visitor from the west,” a kindly local boy, Eddie Hugh Wilson, filled a glass jar with lightning bugs and presented them to the weepy child “as a glowing toy.”

Ralph left Abbeville just before one of the more heinous crimes in its history. On October 21, a mob of whites dragged Anthony Crawford, one of the most prosperous black farmers in the region, from a local jail after the sheriff had arrested him for insulting a white man. The mob then lynched him. Ralph would not visit Abbeville again. Less than two years later, on May 23, 1918, Alfred died. Proud to be an Ellison, Ralph would learn about his paternal grandfather later in life. Alfred had been born a slave in South Carolina in 1845, had remained illiterate, but had also shown uncommon intelligence, integrity, and grit during the perilous Reconstruction. After the war he married Harriet, who was virtually white, and settled down with her in Abbeville. At first, they both worked in some form of domestic service. He also entered Republican Party politics during the brief postwar period when black voters outnumbered their white counterparts in the community. He was an important member of the black Union League, which aimed to preserve the advances made after Emancipation. He tried all his life to keep up with the flux of current events, and to recognize the maneuverings of power about him. His reward was first a post as constable, then as town marshal in Abbeville. Charged with preserving order among blacks and whites, he gained a reputation for being fair to all.

When Reconstruction ended with the Hayes-Tilden Compromise and the withdrawal of federal troops from the South in April 1877, Alfred’s position became tenuous. Whites stepped up their efforts to recapture power and influence in the region. In elections held the previous year, violence had disrupted sleepy Abbeville. The white Abbeville Medium made it clear that “the Democratic party means to carry this state in the next election . . . by fair or foul means.” Many blacks sank into a kind of neo-slavery, or headed north or west. Alfred Ellison was different. When whites killed one of his closest friends, he was defiant. On one occasion, he strode down the main street in Abbeville, trailed by unfriendly whites. “If you’re going to kill me,” he challenged them, “you’ll have to kill me right here because I’m not leaving. This is where I have my family, my farm and my friends; and I don’t plan to leave.” Soon, whites stripped him and other blacks of power. In 1877, Lewis was born, after three daughters. Six other children came later. The family was never destitute; Alfred’s prestige remained high in the black community, and not without substance in the white. Owning a valuable lot of land in town, he also maintained a horse-drawn dray that earned him money, especially during the cotton season. At times, he and his brothers built trestles for the Southern Railroad. In 1884, he made the local news briefly. “Big Alfred” Ellison, as a white newspaper reporter called him, got into a fistfight with “Beef Sam [Marshall], both tremendous specimens of physical manhood,” when tempers flared as they were moving a piano to the train depot. Ellison was thrashing Beef Sam when Sam stuck a knife three inches into his stomach. Ellison recovered. After his wife and one of their children perished in a house fire, the family’s standing was such that the white newspaper carried a notice of Harriet’s death without reference to her race.

Unlike Alfred, young Lewis Ellison learned to read and write, although the extent of his formal education is unknown. Like his father, he was brave. On May 31, 1898, at the age of twenty-one, he responded to President William McKinley’s national call to arms against Spain in Cuba and the Philippines by traveling to Atlanta, where he joined the U.S. Army as a volunteer. After basic training in Georgia, he was assigned to Company F of the 25th United States Colored Infantry. Although family lore placed Lewis with Company F and Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders at the battle of San Juan Heights, it’s clear that he was not in Cuba at the time. He was sent to the Philippines, the other major theater of the Spanish-American War, in 1899. Showing courage under fire, he rose to the rank of lance corporal. Family lore also had him serving in the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion in China, but no evidence exists of that service either. However, two recorded episodes indicate that Lewis had become disillusioned with the Jim Crow army. First, he was demoted to the rank of private. Then, on April 9, 1901, he was court-martialed. He had refused to obey orders to drill in hot, humid weather as punishment for allegedly gambling (he was apparently sick with malaria). The court sentenced him to two years at hard labor. Released later that year, he was dishonorably discharged.

What might have spelled social disaster for a young white man was not as heavy a burden for a black man, whose opportunities were already constricted by Jim Crow. Returning to Abbeville around 1901, Lewis started an ice-cream parlor and candy store. The venture fizzled. Nevertheless, he had enough money in 1902 to finance a mortgage of $125 on his father’s house and land. At some point, he took a job with a construction company in Chattanooga, Tennessee, that specialized in high-rise steel-and-concrete buildings. Soon, he found an enticing reason to stay at home in Abbeville. Among his friends was a handsome young couple—Maston Watkins, a fireman employed by the Southern Railroad, and his attractive wife, Ida Milsap “Brownie” Watkins, from the farming town of White Oak in southeastern Georgia, who had attended Ferguson-Williams Academy in Abbeville. One day, when Watkins was at his job on a train, a group of idle young whites placed a skiff on the tracks to see what would happen. The train derailed, and Watkins was killed. Lewis consoled Brownie, which turned into love and, eventually, marriage. Within a month of their marriage, the couple left Abbeville for a new life in the West.

In April 1910, they were living in Oklahoma City. Starting out as a common street laborer, Lewis soon returned to construction work. For a while, as a foreman, he hired and fired workers. Later, his son Ralph took pride in knowing that his father had helped to build some of the most impressive buildings in the city. Sprawling over the largest municipality in the United States, Oklahoma City should have provided ample opportunity for an experienced construction worker, but Jim Crow ruled even before the state was born in 1907, and Lewis could go only so far in any white-owned business there. In 1907, the populist Democratic politician William H. “Alfalfa Bill” Murray, then president of the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention (and much later a governor of the state), told whites that while “we must provide the means for the advancement of the negro race, and accept him as God gave him to us and use him for the good of society,” the black man “must be taught in the line of his own sphere, as porters, boot-blacks and barbers, and many lines of agriculture. . . . It is an entirely false notion that the negro can rise to the level of a white man in the professions or become an equal citizen to grapple with public questions.” Unless they worked for themselves, blacks got only menial jobs. By now most realized that emigration to Oklahoma probably had been a mistake, yet another black dream frustrated by whites. So Lewis believed. Late in April 1912, when he wrote to Ida from Texas, he mourned the fact that Oklahoma had brought him “much worry and much grief. I am sorry there ever was such a place.” He hoped that his luck would change soon: “I don’t want and don’t intend to be there another winter.”

As it turned out, he endured four more Oklahoma winters. Often he was away, working and saving money. At such times he was solicitous of his wife. “Your baby is sorry he cannot come to his baby when she wants him,” he wrote once to her. “I know how you feel about that and I will pay you well when I get there.” Back in Oklahoma City he started his ice and coal business and planned to buy a house (though he now owned his father’s old house in Abbeville). He and Ida were living in a rooming house when Dr. Wyatt H. Slaughter, the leading black physician in Oklahoma City, delivered Ralph. Needing more space, they rented a house not far away, and then another, on North Byers, surrounded by whites, as Lewis tried to make his family comfortable and give his son a secure start in the world.

When he died in 1916, Lewis left behind the well-thumbed “thick anthology of poetry” that became one of Ralph’s dearest possessions. What did his father know of Emerson, really? Lewis’s letters to Ida—the few that have survived—suggest a poor education, though it’s possible that he had started life with certain interests and tastes only to have them, and his entire sensibility, coarsened by racism. This was, after all, the main purpose of Jim Crow laws and conventions, to reduce blacks to neo-slavery. It’s also possible that his choice of Ralph’s resounding full name was sparked by the fact that his boy was born in a house owned by a man named Jefferson Davis Randolph, who had named his eldest son Thomas Jefferson Randolph. Only late in life did Ralph assert that Emerson had meant much not only to his father but also to other blacks in Oklahoma. “I can’t forget Emerson’s powerful force in the life of my father,” Ralph wrote then, “or the spiritual and intellectual support he provided several of my teachers and community leaders.” According to Ralph, “Emerson’s voice rang loud in Negro communities and influenced my own elders’ decision to seek a broader freedom out in the Territory. . . . Emerson got to me in the classroom no less than at home; in drug store, barbershop, and dental chair, as well as on the playing field. He was also a spur to some of my father’s white friends, and thus sponsored a community of hope.”

The pretentious name would embarrass Ralph for much of his early life, when he sometimes used to claim that Ralph Waldo Ellison was a boy who lived next door. Then, as a teenager, he reconciled himself to, and even embraced, his full name. He didn’t embrace the “hidden name and complex fate” because he came to believe in Emerson’s transcendentalism. Instead, claiming the full American heritage, he began to treasure his nominal connection to the so-called American Renaissance, when Ralph Waldo Emerson, Herman Melville, Walt Whitman, and Henry David Thoreau, among others, penned some of the most influential works of American literature. Ralph would see this movement as a golden moment almost unparalleled in the evolution of the nation. In the Age of Emerson, abolitionist moral fervor had made the black man—the slave—the one true symbol of the American conscience. He also then came to appreciate, however faintly traced, his father’s ambition for him. “After I began to write and work with words,” he recalled, “I came to suspect that he was aware of the suggestive powers of names and of the magic involved in naming.”

Thus the link between father and son continued long after Lewis’s death. Ironically, the son probably wouldn’t have become famous if his father had lived. Protected, perhaps even cosseted, by his father’s love, he would probably have escaped the wounds of poverty, loneliness, and despair that came howling in the wake of Lewis’s death. Later, he resented suggestions that his father’s death had marred him. “What quality of love sustains us in our orphan’s loneliness,” he asked, in words he himself stressed, “and how much is thus required of fatherly love to give us strength for all our life thereafter?” He protested—perhaps too much—against the idea that his father’s death might have crippled him: “What statistics, what lines on whose graphs can ever convince me that by his death I was fatally flawed and doomed—afraid of women, derelict of duty, sad in the sack, cold in the crotch, a rolling stone in social space, a spiritual delinquent, a hater of self—me in whose face his image shows?” As Ralph told it, his mother’s reverence of his father’s memory had made all the difference: “His strength became my mother’s strength and my brother and I the confused, sometimes bitter, but most often proud, recipients of their values and their love.”

Nevertheless, as a youth he would be “bemused by a recurring fantasy in which, on my way to school of a late winter day I would emerge from a cold side street into the warm spring sun and there see my father, dead since I was three, rushing toward me with a smile of recognition and outstretched arms. And I would run proudly to greet him, his son grown tall.” Astutely, Ralph would later define the blues, which may be at the core of modern African-American artistry, as “an impulse to keep the painful details and episodes of a brutal experience alive in one’s aching consciousness, to finger its jagged grain, and to transcend it, not by the consolation of philosophy but by squeezing from it a near-tragic, near-comic lyricism.” For him, the most dangerously “jagged grain,” fingered in his youth and still wounding in his adult years, would be his father’s untimely death. Only eventually would Ralph learn to make art out of this loss, and hope thus to transcend it.

The new life of poverty started almost at once. Finding money to bury Lewis was hard. His body had begun to rot and stink in the summer heat, as Ida told Ralph later, before she was able to bury him in Fairlawn Cemetery. Fortunately, she found a job quickly, as a nursemaid for a Jewish family. Lewis had counted several whites, including several members of the small Jewish community, among his friends. Now working in service for the first time, even as she cared for her own infant, Herbert, Ida would spend the rest of her life mainly as a hotel maid or a janitor. At first, people rushed to help her. Co-worshippers at Avery Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church moved her into its vacant parsonage. She made friends easily. However, as Ralph grew toward adolescence and young manhood, he watched his mother slip down the social ladder until, in the end, she had lost whatever cachet she had brought with her to Oklahoma as a pretty young bride.

No one was more important to her and her little boys than the Randolphs, in whose rooming house Ralph had been born. Heading the family were Jefferson Davis (J.D.) Randolph and his wife, Uretta. Their eldest child, Edna Randolph Slaughter, was for some years Ida’s closest friend; Edna was the wife of Dr. Wyatt Slaughter, the wealthy, property-acquiring physician who had delivered Ralph. After supper in the evenings, Ida, Ralph, and Herbert sometimes went window-shopping with Edna and her princely children, Wyatt Jr. and Saretta. Edna’s two younger sisters, Camille and Iphigenia (“Cute”), were like older sisters to the Ellison boys. Edna’s brothers—the dentist Dr. Thomas Jefferson “Bud” Randolph and the pharmacist Dr. James L. “Jim” Randolph—also took a lively interest in young Ralph. Separately, Tom and Jim would employ him even before he was a teenager.

The Randolphs and the Slaughters were a prominent part of the black leadership of Oklahoma City, which included men and women in business, religion, medicine, dentistry, education, and law. These people both tested segregation and sometimes grew rich from it. For many years, Jim Crow had caged the city’s blacks into scattered pockets. After World War I, however, one area emerged to consolidate the power of the community. This neighborhood was near the thriving downtown district, as the city boomed as a result of the state’s agriculture and abundance of oil wells. Its disadvantages included being close to the railroad tracks that served the bustling stockyards (soon to become the largest cattle market in the world). It was also close to the city’s major red-light district, where prostitutes of all colors plied their trade in segregated whorehouses.

By the early 1920s, in Ralph’s boyhood, the heart of black life in Oklahoma City would be the vibrant block on Second Street between Central and Stiles that came to be known locally as “Deep Second” or “Deep Deuce.” This block housed the community’s drugstores, doctors’ offices, funeral homes, hotels, haberdasheries, restaurants, pool halls, and repair shops, as well as its crusading newspaper, the Black Dispatch. Here also were the Aldridge Theater (hailed as the finest theater for blacks south of Chicago) and Slaughter’s Dance Hall (taking up the third floor of Dr. Slaughter’s biggest building). Between visiting celebrities such as Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong, or hot local talent such as the Blue Devils Orchestra, Deep Second made Oklahoma City second only to Kansas City among jazz centers west of Chicago. The major churches, too, were there or nearby. On East California stood the main school for blacks, the combined Douglass (Colored School) Elementary School and High School, as officials called it. In 1919, Ralph would enter the first grade at Douglass; aside from brief stints elsewhere, he would study there until finishing in 1932 as a member of the class of 1931.

Before Ralph became thoroughly familiar with Deep Second, including its taverns and dancehalls, he led a sheltered life as Ida, his Aunt Lucretia and her children, and the Randolph and Slaughter clans tried to fill the terrible void caused by his father’s death. Although Aunt Lucretia was a formal woman, she dearly loved her brother’s two boys; her children also showered gifts and favors on their young cousins. Lucretia’s irreverent son, Tom, was much older than Ralph but never played the serious adult with him. Instead, he treated him more like a pal. For fifty years a brakeman on the Frisco Railroad, Tom loved whiskey, cigars, fishing, tinkering with cars, and traveling. “He was also a ladies man,” Ralph noted, “whose attraction for good looking young women must surely have influenced my own taste by the time I reached adolescence.”

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Startling, illuminating. . . . [Rampersad] treats Ellison as a man, not as a deity.”—The New Yorker“Astute . . . revelatory. . . . Consistently intriguing.” —The Washington Post Book World“Illuminating and richly reported. . . . Rampersad is uniquely qualified to examine the Ellison case.” —The New York Times Book Review“Rampersad is as meticulous as he is graceful.” —Newsday

Descriere

On the strength of just one novel, as well as a series of lasting essays in cultural criticism, Ellison stands as one of the major literary figures of the last century. Rampersad tells the story of Ellison's long apprenticeship as a musician and writer and his long life, full of honors and frustrations.